Abstract

The presence of donor‐specific anti‐HLA antibodies (DSAs) is associated with increased risk of graft failure after kidney transplant. We hypothesized that DSAs against HLA class I, class II, or both classes indicate a different risk for graft loss between deceased and living donor transplant. In this study, we investigated the impact of pretransplant DSAs, by using single antigen bead assays, on long‐term graft survival in 3237 deceased and 1487 living donor kidney transplants with a negative complement‐dependent crossmatch. In living donor transplants, we found a limited effect on graft survival of DSAs against class I or II antigens after transplant. Class I and II DSAs combined resulted in decreased 10‐year graft survival (84% to 75%). In contrast, after deceased donor transplant, patients with class I or class II DSAs had a 10‐year graft survival of 59% and 60%, respectively, both significantly lower than the survival for patients without DSAs (76%). The combination of class I and II DSAs resulted in a 10‐year survival of 54% in deceased donor transplants. In conclusion, class I and II DSAs are a clear risk factor for graft loss in deceased donor transplants, while in living donor transplants, class I and II DSAs seem to be associated with an increased risk for graft failure, but this could not be assessed due to their low prevalence.

Keywords: alloantibody, clinical research/practice, graft survival, kidney failure/injury, kidney transplantation, kidney transplantation/nephrology, living donor

Short abstract

Via a retrospective multicenter study, the authors investigate the impact of pretransplant donor‐specific HLA antibodies on long‐term graft survival in deceased and living donor kidney transplantations.

Abbreviations

- AKME

adjusted Kaplan–Meier estimator

- CDC‐XM

complement‐dependent cytotoxicity crossmatch

- CI

confidence interval

- CIT

cold ischemia time

- DBD

donation after brain death

- DCD

donation after cardiac death

- DSA

donor‐specific HLA antibody

- FCXM

flow cytometry crossmatch

- HR

hazard ratio

- IL

interleukin

- MFI

median fluorescence intensity

- MMF

mycophenolate mofetil

- NOTR

Netherlands Organ Transplant Registry

- SAB

single antigen bead

1. INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplant is the best treatment option for patients with end‐stage renal disease.1 The discovery and development of potent immunosuppressive drugs that are able to prevent or treat rejection have greatly improved short‐term graft survival rates over the past 50 years.2 Despite these advances, various large registries show graft failure rates of approximately 10% within the first year after transplant, increasing to up to 40% at 10 years after transplant. To further improve the outcome of kidney transplant, there is a clear need for parameters that enable risk stratification for graft failure.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

In the Eurotransplant region, the presence of donor‐specific HLA antibodies (DSAs) against a potential donor kidney causing complement‐mediated lysis8 is considered a contraindication for transplant. These antibodies can be detected with the complement‐dependent cytotoxicity crossmatch assay (CDC‐XM), which has been the gold standard since 1969. With the more recently developed single antigen bead (SAB) assays, DSAs can be detected with increased sensitivity and specificity,9 but the relation between these SAB assay–detected antibodies and clinical outcome is still unclear.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 The presence of SAB assay–detected antibodies that do not cause a positive CDC‐XM is not a contraindication for transplant but may indicate an increased immunological risk for rejection and allograft loss.15

It is well known that graft survival rates in patients who received a living donor kidney are higher than the rates in recipients of a deceased donor kidney.16 While recent large‐cohort studies of the impact of DSAs on graft survival have mainly focused on deceased donor transplants,17, 18, 19 the effect of SAB assay–detected DSAs on living donor transplants has not been studied in large cohorts. In a Japanese single‐center study, 324 living donor kidney transplant recipients were analyzed to investigate the outcome of the 92 kidney transplant recipients with DSAs in combination with anti–blood type, anti–HLA antibodies, or both; all were desensitized before transplant.20 The authors reported no significant difference in graft survival of the different groups compared with the no‐DSAs group at 1 and 5 years after transplant. As far as we could find, there were no large cohorts describing the effect of pretransplant DSAs with negative CDC‐XM in exclusively living donor kidney transplants without desensitization treatment. Orandi et al21 studied the outcomes of incompatible living donor kidney transplants based on the risk determined by using the SAB assay, flow cytometry crossmatch (FCXM), or CDC‐XM and found that patients with a positive SAB assay and a negative FCXM (n = 185) who were desensitized had similar graft survival as a large group of compatible patients (n = 9669), while patients with a positive FCXM (n = 536) or a positive CDC‐XM (n = 304) experienced an increased risk of graft loss. Another study about living donor transplants performed after a positive FCXM (n = 41) reported that the long‐term survival was worse in desensitized recipients compared with matched recipients with a negative FCXM (n = 41).22

In a single‐center study, including both living and deceased donor transplants, it was shown that patients with combined pretransplant HLA class I and II DSAs had an increased risk of graft loss.23 As part of Dutch national Profiling Consortium of Antibody Repertoire and Effector (PROCARE) functions, all kidney transplants performed in The Netherlands between 1995 and 2006 were evaluated retrospectively.24 This cohort was selected for several reasons: allocation or choice of immunosuppressive therapy was not influenced by the results of SAB assay–defined DSAs, patients had at least 10 years of follow‐up and relatively modern immunosuppression. We analyzed whether SAB assay–detected DSAs against HLA class I and/or II influence long‐term graft survival in deceased and living donor kidney transplants.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients, sera, and clinical data

This multicenter study included all 6097 kidney transplants performed between January 1995 and December 2005 in all Dutch transplant centers. Patients were primarily white. In all cases, the T cell CDC‐XM with current and historic highest sera was negative. Historic cytotoxic HLA antibodies were assigned as unacceptable for allocation in the Eurotransplant region. Bead assay–defined DSAs were not considered as risk factors in the matching procedure at that time and therefore had no influence in immunosuppressive treatment. Informed consent for data collection and use of leftover sera was obtained from all subjects. Patients and donors investigated were predominantly white. The use of sera and experimental protocols was approved by the Research Ethics Committee for Biobanks and the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht. Moreover, this study was performed in accordance with the FEDERA Code of Conduct.

We obtained baseline and clinical follow‐up transplant data from the Netherlands Organ Transplant Registry (NOTR), which was > 95% complete at time of this study. Clinical follow‐up was recorded at 3 months, 12 months, and yearly thereafter for at least 10 years. The primary endpoint of the study is graft failure, defined as loss of kidney function when the patient returns to dialysis or receives a retransplant. In the analysis of death‐censored graft failure, recipients who died with a functioning graft were censored at the time of death.

Pretransplant patient sera could be collected from 4787 (78%) transplants of 4585 patients (some patients underwent > 1 transplant). For 17 transplants, patients were lost to follow‐up (NOTR), and 46 transplants were excluded because the kidney failed during surgery or shortly thereafter due to technical nonimmunologic problems. We included 4724 transplants in the analysis.

2.2. Detection and definition of DSAs

The presence of HLA antibodies (HLA‐Abs) in the pretransplant sera, used for pretransplant crossmatch, was assessed retrospectively in a central laboratory as described previously.25 In brief, sera were first tested for the presence of HLA class I and class II antibodies by using Lifecodes LifeScreen Deluxe (Immucor Transplant Diagnostics, Stamford, CT). Subsequently, the sera positive for HLA class I and/or class II were analyzed by using Lifecodes SAB assay class I and/or II kits (Immucor Transplant Diagnostics) to determine the exact specificity of the HLA‐Abs. The LABScan 100 flow analyzer (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA) was used for data acquisition. Bead positivity was defined according to the manufacturer's instructions, requiring a minimal signal:background ratio to be reached (described elsewhere25), which leads to virtually identical results as when taking an absolute median fluorescence intensity (MFI) cutoff of 750. The presence of SAB assay–detected DSAs was assigned by comparing the SAB assay–detected HLA‐A/B/DR/DQ antibody specificities on serologic level with the split‐level HLA typing of the donor. For 70 antigens (47 of which HLA‐DQ) in 64 transplants, we had only broad‐level typing information at our disposal and could not determine whether antibodies against some of the possible splits were DSAs. These donor antigen–recipient antibody combinations were not considered as DSAs in the analyses in this study. If we assigned all these antigens as DSAs, similar results and the same conclusions were obtained (data not shown).

2.3. Statistical analysis

Differences in patient, donor, and transplant characteristics between the DSA‐positive and ‐negative groups were assessed by using the χ2 test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Death‐censored graft survival was assessed by using the adjusted Kaplan–Meier estimator (AKME) based on inverse probability weighting (IPW).26 The following covariates were considered for adjustment: recipient and donor age, recipient and donor sex, year of transplant, type of donor, cold ischemia time (CIT), retransplant, graft function, interleukin (IL)‐2 receptor blocker, number of HLA‐A/B/DR mismatches, transplant and highest percent PRA. We adjusted for recipient age (quadratic) and donor age (quadratic), donor type (living or deceased; for the total cohort only), CIT (for donation after brain death [DBD] and donation after cardiac death [DCD]), time on dialysis in years (quadratic), and induction therapy with IL‐2 receptor blocker (Figure S1). The other covariates were not used for various reasons motivated as given in the Supplementary Information. Hazard ratios (HRs) and confidence intervals (CIs) were derived by using multivariable Cox regression. Validity of Cox model assumptions were verified by evaluating uncorrected Kaplan–Meier (cumulative), Martingale residual, and Schoenfeld residual plots. Various covariates, specified in the Supplementary Information, were used in both the AKME and Cox regressions, to adjust for confounding. Two hundred twenty‐six missing CITs were imputed by using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) single imputation; no additional values were missing. Statistical analyses were performed with R (version 3.2.2) and SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) software.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics

Patient, donor, and transplant characteristics stratified according to the presence of pretransplant DSAs are summarized in Table 1. Of 4724 patients, 567 (12%) had pretransplant DSAs. The mean age at transplant was significantly lower in recipients with DSAs. The DSA group contained a higher proportion of female recipients (59% vs 38%), and PRA values determined with CDC were clearly related to the presence of DSAs. Additionally, there were significantly more retransplants in the DSA (47.6%) group. In 33% of the transplants without DSAs, the kidney was donated by a living donor, whereas 24% of the transplants with preformed DSAs had living donors. Most patients initially received a triple immunosuppressive regimen consisting of steroids, cyclosporine or tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. In addition, 26% of the patients received induction therapy, with either a T cell–depleting antibody (4%) or an IL‐2 receptor–blocking antibody (22%). Minimal follow‐up time was 10 years after transplant.

Table 1.

Patient, donor, and transplant characteristics

| Characteristics | No DSAs (n = 4157) | DSAs (n = 567) | P‐value | Total cohort (N = 4724) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | ||||

| Age at transplant, y, mean ± SD | 45.6 ± 14.4 | 44.2 ± 13.9 | .01a | 45.4 ± 14.4 |

| Female sex, n | 1561 (37.6) | 333 (58.7) | <.001b | 1894 (40.1) |

| PRA at time of transplant, %, mean ± SD | 3.5 ± 12.9 | 24.4 ± 30.7 | <.001a | 6.0 ±17.5 |

| Highest PRA, %, mean ± SD | 9.8 ± 21.0 | 43.6 ± 36.3 | <.001a | 13.8 ± 25.8 |

| Dialysis | .0004b | |||

| No, n (%) | 472 (1.4) | 43 (7.6) | 515 (10.9) | |

| Yes—hemodialysis, n | 2140 (51.4) | 332 (58.6) | 2472 (52.3 ) | |

| Yes—peritoneal dialysis, n | 1529 (36.8) | 186 (32.8) | 1715 (36.3) | |

| Unknown, n (%) | 16 (0.4) | 6 (1.1) | 22 (0.5) | |

| Time on dialysis, y, mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 2.4 | 3.4 ± 3.0 | <.0001a | 2.8 ± 2.5 |

| Donor | ||||

| Donor age, y, mean ± SD | 44.4 ± 14.9 | 44.0 ± 15.8 | 1.00a | 44.4 ± 15.0 |

| Donor female sex, n | 2128 (51.2) | 258 (45.5) | .01b | 2386 (50.5) |

| Type of donor | <.001b | |||

| Living, n | 1350 (32.5) | 137 (24.2) | 1487 (31.4) | |

| Deceased—DBD, n | 2076 (49.9) | 351 (61.9) | 2427 (51.4) | |

| Deceased—DCD, n (%) | 731 (17.6) | 79 (13.9) | 810 (17.2) | |

| Cold ischemia time | ||||

| Deceased donors, h, mean ± SD | 21.7 ± 7.3 | 22.8 ± 6.8 | .001a | 21.9 ± 7.2 |

| Living donors, h, mean ± SD | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | .53 a | 2.5 ± 1.5 |

| Transplant | ||||

| Retransplant, n (%) | 453 (10.9) | 270 (47.6) | <.001b | 723 (15.3) |

| HLA‐A/B/DR broad mismatches, mean ± SD | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | .15a | 2.4 ± 1.5 |

| Induction therapy | ||||

| IL‐2 receptor blocker, n (%) | 913 (21.9) | 109 (19.2) | .14b | 1022 (21.6) |

| T cell–depleting antibody,cn (%) | 145 (3.6) | 39 (6.9) | <.001b | 184 (3.9) |

| Initial immunosuppression, n (%) | ||||

| Steroids | 4069 (97.9) | 547 (96.5) | .04b | 4616 (97.7) |

| MMF/azathioprine | 3163 (76.1) | 442 (78) | .20b | 3605 (76.3) |

| Cyclosporine/tacrolimus | 3892 (93.6) | 542 (95.6) | .07b | 4434 (93.9) |

| Sirolimus | 260 (6.3) | 26 (4.6) | .12b | 286 (6.1) |

| Other | 555 (13.4) | 53 (9.4) | .008b | 608 (12.9) |

| Unknown | 14 (0.3) | 3 (0.5) | .47b | 17 (0.4) |

DBD, donation after brain death; DCD, donation after cardiac death; DSA, donor‐specific HLA antibody; IL, interleukin; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables.

χ2 test for categorical variables.

T cell–depleting antibody therapy: ALG, ATG, OKT3 monoclonal antibodies.

3.2. Impact of pretransplant DSAs on long‐term graft survival

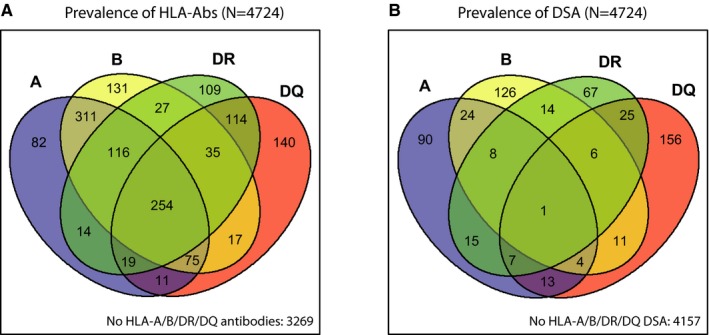

Using SAB assays, we determined the presence of antibodies against HLA‐A/B/C/DR/DR51‐53/DQ/DP antigens, either donor specific or not. As shown in a Venn diagram (Figure 1A), in 3269 (69%) of 4724 transplants, the recipients had no pretransplant antibodies against HLA‐A/B/DR/DQ antigens. The combination of anti–HLA‐A and anti–HLA‐B antibodies (without anti–HLA‐DR/DQ antibodies) was relatively frequent (311/4724 [7%]), as was the combination of antibodies against all 4 antigens (254/4724 [5%]). Antibodies against a single HLA molecule were most frequent for HLA‐B and ‐DQ. The prevalence of antibodies exclusively directed against HLA‐C, ‐DR51‐53, or ‐DP was low in our cohort with 4, 13, and 19 positive sera, respectively (Table S1). Donor‐specific antibody prevalence against the donor HLA loci A, B, DR, and DQ is depicted in Figure 1B. In 4157 (88%) of the 4724 kidney transplants, recipients harbored no pretransplant DSAs against these antigens.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of pretransplant HLA‐Abs and donor‐specific HLA antibodies (DSAs) in the total cohort (N = 4724). A. Venn diagram showing the prevalence of pretransplant HLA‐A/B/DR/DQ HLA‐Abs. B. Venn diagram showing the prevalence of pretransplant HLA‐A/B/DR/DQDSAs [Color figure can be viewed at http://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The AKME showed a 10‐year death‐censored graft survival of 78% (95% CI 77%‐80%) for the 4157 patients without and 66% (95% CI 64%‐67%) for the 567 patients with DSAs in pretransplant sera (Figure 2A). The multivariable analysis, adjusted for the same covariables, showed that the presence of DSAs was associated with a higher risk of graft failure (Table 2; HR 1.77, 95% CI 1.51‐2.08).

Figure 2.

Long‐term graft survival of kidney transplants according to the presence of pretransplant donor‐specific HLA antibodies (DSAs). A. Adjusted Kaplan–Meier estimates (AKME) for death‐censored graft survival according to the presence of pretransplant DSAs for the total cohort including deceased‐ and living‐donor transplants (N = 4724). B. AKME for death‐censored graft survival according to the presence of pretransplant DSAs for living‐donor transplants only (n = 1487). C. AKME for death‐censored graft survival according to the presence of pretransplant DSAs for deceased‐donor transplants only (n = 3237). All AKME were adjusted for the same covariates: recipient age (quadratic) and donor age (quadratic), donor type (living or deceased; for the total cohort only), cold ischemia time (for donation after brain death [DBD] and donation after cardiac death [DCD]), time on dialysis in years (quadratic), and induction therapy with interleukin‐2 receptor blocker [Color figure can be viewed at http://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 2.

Multivariable analyses of DSAs using Cox proportional hazards model

| No. (%) of transplants with DSAs | Hazard ratio DSAs | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort (N = 4724) | 567 (12) | 1.77 | 1.51‐2.08 |

| Living donors (n = 1487) | |||

| All | 137 (9) | 1.42 | 0.95‐2.10 |

| DSA class I only | 58 (4) | 1.46 | 0.83‐2.55 |

| DSA class II only | 61 (4) | 1.17 | 0.64‐2.14 |

| DSA class I and II | 18 (1) | 2.84 | 1.05‐7.69 |

| Early failures (< 1 y) | 137 (9) | 1.69 | 0.76‐3.77 |

| Late failures (≥1 y) | 128 (9) | 1.35 | 0.86‐2.12 |

| Deceased donors (n = 3237) | |||

| All | 430 (13) | 1.86 | 1.56‐2.21 |

| DSA class I only | 182 (6) | 1.93 | 1.50‐2.47 |

| DSA class II only | 187 (6) | 1.76 | 1.37‐2.26 |

| DSA class I and II | 61 (2) | 1.96 | 1.29‐2.98 |

| Early failures (< 1 y) | 430 (13) | 1.76 | 1.33‐2.33 |

| Late failures (≥ 1 y) | 352 (12) | 1.97 | 1.56‐2.45 |

CI, confidence interval; DSA, donor‐specific HLA antibody. In this multivariable analysis we adjusted for differences in the following covariates: recipient age (quadratic), donor age (quadratic), donor type (living or deceased), cold ischemia time in hours for donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after cardiac death (DCD), time on dialysis in years (quadratic), and induction therapy with interleukin‐2 receptor–blocking antibody. The hazard ratios of the covariates are shown in Table S6.

Because our cohort contains a relatively high proportion of living donors, we analyzed the impact of DSAs on long‐term graft survival according to donor status. For the living donor transplants (n = 1487), there was only a limited and nonsignificant relation between pretransplant DSAs and 10‐year death‐censored graft survival, which was 78% and 84% for patients with and without DSAs, respectively (Figure 2B, P = .07). For the deceased donor transplants (n = 3237), the 10‐year death‐censored graft survival was 60% and 76% for patients with and without DSAs, respectively (Figure 2C, P < .0001), demonstrating a clear adverse effect of pretransplant DSAs.

These findings were confirmed in a multivariable analysis (Table 2), where the presence of pretransplant DSAs had no significant influence on graft survival in living donor transplants (HR 1.42, 95% CI 0.95‐2.10). In contrast, the presence of DSAs was significantly associated with a higher risk of graft failure after deceased donor transplants (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.55‐2.19). In Table 3, the patient, donor, and transplant characteristics of living donor (n = 1487) and deceased donor (n = 3237) transplants are summarized. In addition, the characteristics for living and deceased donor transplants were further subdivided for transplants with DSAs (Table S2), with class I DSAs only (Table S3), with class II DSAs only (Table S4), and with class I and II DSAs (Table S5).

Table 3.

Patient, donor, and transplant characteristics for deceased and living donor transplants

| Characteristics | Deceased donor (N = 3237) | Living donor (N = 1487) | P‐value | Total cohort (N = 4724) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | ||||

| Age at transplant, y, mean ± SD | 46.9 ± 14.1 | 42.3 ± 14.5 | <.001a | 45.4 ± 14.4 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 1309 (40.4) | 585 (39.4) | .47b | 1894 (40.1) |

| PRA at time of transplant, %, mean ± SD | 7.0 ± 19.0 | 3.8 ± 13.4 | <.001a | 6.0 ±17.5 |

| Highest PRA, %, mean ± SD | 16.5 ± 28.3 | 8.0 ± 17.9 | <.001a | 13.8 ± 25.8 |

| Dialysis, n (%) | <.001b | |||

| No | 150 (4.6) | 365 (24.6) | 515 (10.9) | |

| Yes—hemodialysis | 1879 (58.1) | 593 (39.9) | 2472 (52.3) | |

| Yes—peritoneal dialysis | 1189 (36.7) | 526 (35.4) | 1715 (36.3) | |

| Unknown | 19 (0.6) | 3 (0.2) | 22 (0.5) | |

| Time on dialysis, y, mean ± SD | 3.4 ± 2.6 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | <.001a | 2.8 ± 2.5 |

| Donor | ||||

| Donor age, y, mean ± SD | 42.8 ± 16.0 | 47.9 ± 11.9 | <.001a | 44.4 ± 15.0 |

| Donor female sex, n (%) | 1517 (47.9) | 869 (58.4) | <.001b | 2386 (50.5) |

| Cold ischemia time, h, mean ± SD | 21.9 ± 7.2 | 2.5 ± 1.5 | <.001a | 15.8 ± 10.8 |

| Transplant | ||||

| Retransplant, n (%) | 562 (17.4) | 161 (10.8) | <.001b | 723 (15.3) |

| HLA‐A/B/DR broad mismatches, mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 1.4 | 2.7 ± 1.6 | <.001a | 2.4 ± 1.5 |

| Induction therapy, n (%) | ||||

| IL‐2 receptor blocker | 655 (20.2) | 367 (24.7) | <.001b | 1022 (21.6) |

| T cell–depleting antibodyc | 133 (4.1) | 51 (3.4) | .26b | 184 (3.9) |

| Initial immunosuppression | ||||

| Steroids, n (%) | 3172 (98.0) | 1444 (97.1) | .058b | 4616 (97.7) |

| MMF/azathioprine | 3163 (76.1) | 442 (78) | <.001b | 3605 (76.3) |

| Cyclosporine/tacrolimus | 3051 (94.3) | 1383 (93.0) | .097b | 4434 (93.9) |

| Sirolimus | 176 (5.4) | 110 (7.4) | <.001b | 286 (6.1) |

| Other | 436 (13.5) | 172 (11.6) | .070b | 608 (12.9) |

| Unknown | 11 (0.3) | 6 (0.4) | .73b | 17 (0.4) |

DBD, donation after brain death; DCD, donation after cardiac death; DSA, donor‐specific HLA antibodies; IL, interleukin; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables.

χ2 test for categorical variables.

T cell–depleting antibody therapy: ALG, ATG, OKT3 monoclonal antibodies.

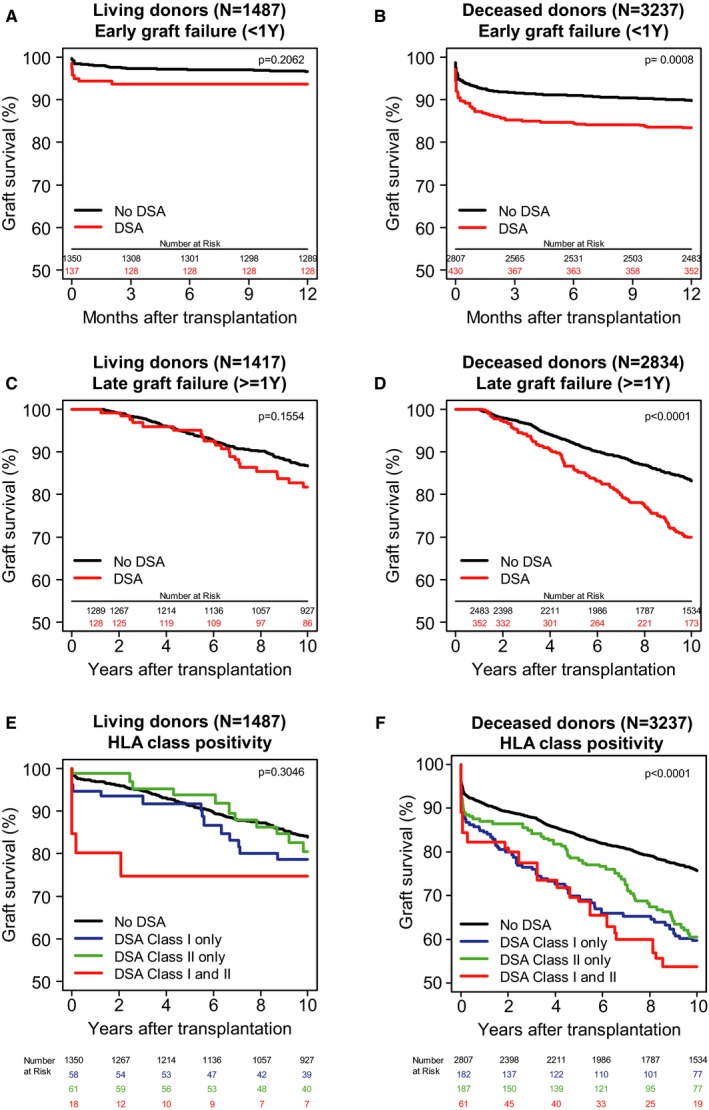

3.3. Impact of pretransplant DSAs on early and late graft failure

The effect of pretransplant DSAs on graft survival was already evident early after transplant (Figure 3A,B). In living donor transplants, 1‐year death‐censored graft survival for patients with and without DSAs was 94% and 96% (Figure 3A), respectively (Table 2; HR 1.69, 95% CI 0.76‐3.77). For deceased donor transplants, we found a similar effect (Figure 3B; HR 1.72, 95% CI 1.31‐2.27).

Figure 3.

Impact of donor‐specific HLA antibodies (DSAs) on graft survival for deceased‐donor transplants. A. Adjusted Kaplan–Meier estimates (AKME) for 1‐year death‐censored graft survival according to the presence of pretransplant DSAs for living‐donor transplants only (n = 1487). B. AKME for 1‐year death‐censored graft survival according to the presence of pretransplant DSAs for deceased‐donor transplants only (n = 3237). C. Analysis of long‐term effect of pretransplant DSAs starting at 1 year after transplant for living‐donor transplants only (n = 1417). D. Analysis of long‐term effect of pretransplant DSAs starting at 1 year after transplant for deceased‐donor transplants only (n = 2834). E. AKME for death‐censored graft survival according to the presence of pretransplant HLA class I (A/B) and/or II (DR/DQ) DSAs for living‐donor transplants only (n = 1487). F. AKME for death‐censored graft survival according to the presence of pretransplant HLA class I (A/B) and/or II (DR/DQ) DSAs for deceased‐donor transplants only (n = 3237). All AKME were adjusted for the same covariates: recipient age (quadratic) and donor age (quadratic), donor type (living or deceased; for the total cohort only), cold ischemia time (for donation after brain death [DBD] and donation after cardiac death [DCD]), time on dialysis in years (quadratic) and induction therapy with interleukin‐2 receptor blocker [Color figure can be viewed at http://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com]

To examine whether pretransplant DSAs also affect the risk of late graft failure, we separately analyzed the graft survival of the patients with surviving grafts at 1 year after transplant. To this end, 70 (for living donor) and 403 (for deceased donor) grafts that failed or were censored in the first year were excluded and graft survival analysis was restarted at 100% (Figure 3C‐D). For living donor transplants, a modest, nonsignificant effect of DSAs was found, with 82% and 87% 10‐year death‐censored graft survival for those with and without DSAs, respectively (HR 1.35, 95% CI 0.86‐2.12). For deceased donor transplants, however, an increased risk of graft failure (HR 1.95, 95% CI 1.56‐2.44) remained with a 10‐year death‐censored graft survival of 70%, compared with 83% for transplants in patients without DSAs. Similar results were found when an early graft failure cutoff of 3 months was used instead of 1 year (data not shown). These data indicate the presence of a short‐ and long‐term effect of DSAs on graft survival in deceased donor transplants. For living donor transplants, no significant effect was found.

3.4. Effect of pretransplant HLA class I and II DSAs on graft survival

Next, we investigated separately the effects of donor‐specific HLA class I (A/B) and HLA class II (DR/DQ) antibodies on kidney graft survival within the living donor transplants. We found no effect on graft survival within 1 year after transplant of pretransplant DSAs against either class I or II antigens only, and only a limited effect of 4% and 5% on the 10‐year graft survival, respectively (Figure 3E; Table 2; HR 1.35, 95% CI 0.86‐2.12). In contrast, in deceased donor transplant, the isolated presence of either class I or class II DSAs was clearly associated with an increased risk of graft failure (HR 1.93, 95% CI 1.51‐2.48; HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.36‐2.24, respectively) with a 10‐year death‐censored graft survival of 60% and 61%, respectively, compared with 76% in transplants with DSA‐negative recipients (Figure 3F).

The combined presence of class I and II DSAs resulted in the poorest graft survival for both donor types, with a decrease from 84% to 75% at 10 years after transplant for living donor grafts (HR 2.84, 95% CI 1.05‐7.69) and a decrease from 76% to 54% for deceased donor grafts (HR 1.90, 95% CI 1.25‐2.88).

4. DISCUSSION

In this multicenter study, we found a limited effect of pretransplant SAB assay–defined DSAs on graft failure in living donor transplants. In contrast, pretransplant SAB assay–defined DSAs are a clear risk factor for graft loss in deceased donor transplantations with a negative CDC‐XM. Further subdivision of the DSAs in deceased donor transplantations revealed that DSAs against either class I or II did constitute a significant risk factor for graft loss and pretransplant DSAs against both HLA class I and class II resulted in the poorest death‐censored graft survival. In living donor transplants, the combination of class I and II DSAs seem to be associated with an increased risk for graft failure, but this could not be assessed due to their low prevalence.

Recently published studies on pretransplant DSAs focused mainly on deceased donor transplants, as these are most prevalent in, for example, France, Germany, and the United States.17, 18, 19 Studies on living donor transplant are scarce; in a single‐center study, where 324 living donor transplants were analyzed, no significant difference in the 5‐year graft survival of patients with DSAs was found compared with patients with anti–blood type antibody, anti–HLA‐Abs, or no DSAs.20 Mohan et al19 reported a meta‐analysis of DSAs detected with, among others, SAB assays and calculated an increased risk for graft failure in the presence of SAB assay–detected DSAs with negative CDC‐XM, similar to our study. The effect of DSAs in living donor transplant has not been investigated so far in large cohorts. In The Netherlands, currently more than half of the kidney transplants are performed with kidneys from living donors, while the 31% in the cohort from 1995 to 2006 provides us with the unique means to study a cohort of 1487 living donor transplants.

The time period of 1995‐2006 was specifically chosen as it ensures sufficient follow‐up with immunosuppressive treatment currently still used, without bias due to results from SAB assays in pretransplant risk assessment, patient/donor selection, or guidance of immunosuppressive treatment after transplant. Because there is no consensus regarding the MFI cutoff that should be used to determine positivity with SAB assays, we defined positivity based on manufacturers’ instructions by using a signal:noise ratio. Using different MFI cutoffs for DSA positivity resulted in comparable effects on long‐term graft survival (Figure S2). DSA class I– and class II–positive transplants have a considerably higher average number of DSAs, average maximum MFI of DSAs, and average cumulative MFI of DSAs (Table S7B‐D). The higher “strength” of DSAs as expressed by these 3 parameters could (partly) explain the worse graft survival of this group. DSA class I and II positivity, however, provides a better risk classifier than we were able to construct from 3 DSA strength parameters in this study. Other studies have shown that DSA assessments using MFI alone may not be sufficient for assessing the potential risk for graft damage and decreased survival. Multiple assays are used, such as Flow‐XM,21, 27 C1q‐SAB assays,17 C3d‐SAB assays,28 or IgG‐subclass analysis.29 Our cohort includes 63 patients participating in the Eurotransplant Acceptable Mismatch program with an HLA antibody profile based on CDC, in some cases supplemented with solid phase assays.30 Inclusion of this patient group did not induce bias as we observed no major impact on our conclusions if we excluded these patients from our cohort (data not shown). We excluded 46 transplants because the kidney failed during surgery or shortly thereafter due to technical nonimmunologic problems. The impact of inclusion and exclusion of these patients on graft survival was equal for both groups (DSAs versus no DSAs).

Our study has a few limitations. Because we collected sera retrospectively, we were able to collect 78% in total. We are mainly missing sera from older transplants of 4 centers, while from the other 3 centers we collected > 90%. Limited information was available on rejection and donor organ quality, and we do not have information on posttransplant (de novo) DSA formation. This is a retrospective cohort of kidney transplants between 1995 and 2005, so the registration of rejections was limited. We have information only on whether patients were treated for a rejection including the date of rejection and, if performed, the date of biopsy. At that time, biopsies were not always performed, and, therefore, some of the registered rejections might not have been actual rejections. On the other hand, rejections might have been missed or not registered. Others have shown that in living donor transplants, DSAs was an important predictor of antibody‐mediated rejection, while this was not the case for graft failure.31 Using the limited rejection data that we had, we observed that patients with pretransplant DSAs had a higher incidence of rejection in living as well as deceased donor transplants (data not shown).

For posttransplant DSAs determined using SAB assays, it was already shown that it has an adverse effect on graft survival.18 For our cohort, we can assess only the potential for confounding by de novo DSAs via the average number of HLA mismatches. Because the DSA‐positive groups have fewer mismatches for all HLA loci (Table S9), we expect to be underestimating rather than overestimating the effect of pretransplant DSAs in that respect. We also find fewer mismatches for all loci in deceased donor transplants. In addition, the difference in impact of DSAs on graft survival between living and deceased donor transplant is likely not due to difference in either DSA strength (Table S7a) or immunization status, as there was no stronger effect of DSAs on graft survival in patients retransplanted with a living donor kidney, than in patients receiving a living donor kidney as first transplant with a much lower level of immunization (Table S8; Figure S1; Figure S4). However, it is known that graft survival rates of poorly HLA‐matched living donor grafts are superior to those of well HLA‐matched deceased donor grafts.16, 32 This can partially be explained by the prolonged CIT in deceased donors but also by inherent factors of the organ due to cardiovascular instability of the donor before nephrectomy, who may play a role.33 Donor kidney quality is of importance when transplanting patients with DSAs. Relevant variables regarding kidney quality are, for example, donor age, (deceased) donor type, CIT, and graft function, which are all available in our database. We corrected in our multivariable analysis analyzing the effect of pretransplant DSAs on graft survival for donor age, donor type, and CIT (CIT only in deceased donor transplant) but not for (delayed) graft function, as this might be caused by the preexistent DSAs.

Interindividual differences in the level of HLA antigen expression on the cell surface have been shown to affect the CDC‐XM,34 indicating that sufficient HLA expression is required to induce effector mechanisms such as complement activation. The limited impact of preformed DSAs against HLA class I or class II in living donor transplant compared with deceased donor transplant might be explained by a lower expression of HLA and adhesion molecules on the endothelial cells in living donor organs compared with those of deceased donors.35 In our cohort of 1487 living donor kidney transplants, the combination of class I and II antibodies occurred in only 18 cases, indicating that the prevalence of this risk factor is relatively low.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that in the presence of negative CDC‐XM, SAB assay–defined DSAs against either HLA class I or HLA class II is a significant risk factor in deceased donor transplant, but this seems not to be the case in living donor transplant. The combined presence of DSAs against HLA class I and II has a much stronger negative impact on graft survival after deceased donor transplant, while in living donor transplants class I and II DSAs seem to be associated with an increased risk for graft failure. However, this could not be assessed due to their low prevalence. Based on these results, we suggest that the combination of class I and II DSAs be taken into account in the allocation of donor kidneys in Eurotransplant region. Moreover, recipients with this combination of DSAs should be considered as patients with a higher risk of graft failure.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by research funding from the Dutch Kidney Foundation Project code CP12.23 Risk assessment of kidney graft failure by HLA antibody profiling.

Kamburova EG, Wisse BW, Joosten I, et al. Differential effects of donor‐specific HLA antibodies in living versus deceased donor transplant. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:2274–2284. 10.1111/ajt.14709

REFERENCES

- 1. Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LYC, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(23):1725‐1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sayegh MH, Carpenter CB. Transplantation 50 years later–progress, challenges, and promises. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(26):2761‐2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ojo AO, Morales JMM, González‐Molina M, et al. Comparison of the long‐term outcomes of kidney transplantation: USA versus Spain. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(1):213‐220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brenner H, Opelz G, Gondos A, Do B. Kidney graft survival in Europe and the United States: strikingly different long‐term outcomes. Transplantation. 2013;95(2):267‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chapman JR, O'Connell PJ, Nankivell BJ. Chronic renal allograft dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(10):3015‐3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pascual M, Theruvath T, Kawai T, Tolkoff‐Rubin N, Cosimi AB. Strategies to improve long‐term outcomes after renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):580‐590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sayegh MH. Why do we reject a graft? role of indirect allorecognition in graft rejection. Kidney Int. Elsevier Masson SAS; 1999;56(5):1967‐1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel R, Terasaki PI. Significance of the positive crossmatch test in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1969;280(14):735‐739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Couzi L, Araujo C, Guidicelli G, et al. Interpretation of positive flow cytometric crossmatch in the era of the single‐antigen bead assay. Transplantation. 2011;91(5):527‐535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aubert V, Venetz JP, Pantaleo G, Pascual M. Low levels of human leukocyte antigen donor‐specific antibodies detected by solid phase assay before transplantation are frequently clinically irrelevant. Hum Immunol 2009;70(8):580‐583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Salvadé I, Aubert V, Venetz J, et al. Clinically‐relevant threshold of preformed donor‐specific anti‐HLA antibodies in kidney transplantation. Hum Immunol 2016;77:483‐489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vaidya S, Partlow D, Susskind B, Noor M, Barnes T, Gugliuzza K. Prediction of crossmatch outcome of highly sensitized patients by single and/or multiple antigen bead Luminex assay. Transplantation. 2006;82(11):1524‐1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mizutani K, Terasaki P, Hamdani E, et al. The importance of anti‐HLA‐specific antibody strength in monitoring kidney transplant patients. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(4):1027‐1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tait BD, Süsal C, Gebel HM, et al. Consensus guidelines on the testing and clinical management issues associated with HLA and non‐HLA antibodies in transplantation. Transplantation. 2013;95(1):19‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Amico P, Hönger G, Mayr M, Steiger J, Hopfer H, Schaub S. Clinical relevance of pretransplant donor‐specific HLA antibodies detected by single‐antigen flow‐beads. Transplantation. 2009;87(11):1681‐1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Laging M, Kal‐van GJ, Haasnoot GW, et al. Transplantation results of completely HLA‐mismatched living and completely HLA‐matched deceased‐donor kidneys are comparable. Transplantation 2014;97(3):330‐336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Loupy A, Lefaucheur C, Vernerey D, et al. Complement‐binding anti‐HLA antibodies and kidney‐allograft survival. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(13):1215‐1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lachmann N, Terasaki PI, Budde K, et al. Anti‐human leukocyte antigen and donor‐specific antibodies detected by Luminex posttransplant serve as biomarkers for chronic rejection of renal allografts. Transplantation. 2009;87(10):1505‐1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mohan S, Palanisamy A, Tsapepas D, et al. Donor‐specific antibodies adversely affect kidney allograft outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(12):2061‐2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ushigome H, Harada S, Nakao M, et al. Living‐donor kidney transplantation with existing anti‐donor specific antibodies at a Japanese single center. Transplant Proc. 2015;47(3):612‐616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Orandi BJ, Garonzik‐Wang JM, Massie AB, et al. Quantifying the risk of incompatible kidney transplantation: a multicenter study. Am J Transplant 2014;14(7):1573‐1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haririan A, Nogueira J, Kukuruga D, et al. Positive cross‐match living donor kidney transplantation: longer‐term outcomes. Am J Transplant 2009;9(3):536‐542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Otten HG, Verhaar MC, Borst HPE, Hené RJ, van Zuilen AD. Pretransplant donor‐specific HLA class I and II antibodies are associated with an increased risk for kidney graft failure. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(6):1618‐1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Otten HG, Joosten I, Allebes W a, et al. The PROCARE consortium: toward an improved allocation strategy for kidney allografts. Transpl Immunol 2014;31(4):184‐190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kamburova EG, Wisse BW, Joosten I, et al. How can we reduce costs of solid‐phase multiplex‐bead assays used to determine anti‐HLA antibodies? HLA. 2016;88(3):110‐119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xie J, Liu C. Adjusted Kaplan‐Meier estimator and log‐rank test with inverse probability of treatment weighting for survival data. Stat Med. 2005;24(20):3089‐3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reinsmoen NL, Lai C‐H, Vo A, et al. Acceptable donor‐specific antibody levels allowing for successful deceased and living donor kidney transplantation after desensitization therapy. Transplantation. 2008;86(6):820‐825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sicard A, Ducreux S, Rabeyrin M, et al. Detection of C3d‐binding donor‐specific anti‐HLA antibodies at diagnosis of humoral rejection predicts renal graft loss. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(2):457‐467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Viglietti D, Loupy A, Vernerey D, et al. Value of donor‐specific anti‐HLA antibody monitoring and characterization for risk stratification of kidney allograft loss. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;28:702‐715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heidt S, Witvliet MD, Haasnoot GW, Claas FHJ. The 25th anniversary of the Eurotransplant Acceptable Mismatch program for highly sensitized patients. Transpl Immunol 2015;33(2):51‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dunn TB, Noreen H, Gillingham K, et al. Revisiting traditional risk factors for rejection and graft loss after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(10):2132‐2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Süsal C, Opelz G. Current role of human leukocyte antigen matching in kidney transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2013;18(4):438‐444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roodnat JI, van Riemsdijk IC, Mulder PGH, et al. The superior results of living‐donor renal transplantation are not completely caused by selection or short cold ischemia time: a single‐center, multivariate analysis. Transplantation. 2003;75(12):2014‐2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hönger G, Krähenbühl N, Dimeloe S, Stern M, Schaub S, Hess C. Inter‐individual differences in HLA expression can impact the CDC crossmatch. Tissue Antigens. 2015;85(4):260‐266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koo DDH, Welsh KI, McLaren AJ, Roake JA, Morris PJ, Fuggle SV. Cadaver versus living donor kidneys: impact of donor factors on antigen induction before transplantation. Kidney Int 1999;56(4):1551‐1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials