Abstract

Introduction

We aimed to determine how serious adverse events in obstetrics were assessed by supervision authorities.

Material and methods

We selected cases investigated by supervision authorities during 2009‐2013. We analyzed information about who reported the event, the outcomes of the mother and infant, and whether events resulted from errors at the individual or system level. We also assessed whether the injuries could have been avoided.

Results

During the study period, there were 303 034 births in Norway, and supervision authorities investigated 338 adverse events in obstetric care. Of these, we studied 207 cases that involved a serious outcome for mother or infant. Five mothers (2.4%) and 88 infants (42.5%) died. Of the 207 events reported to the supervision authorities, patients or relatives reported 65.2%, hospitals reported 39.1%, and others reported 4.3%. In 8.7% of cases, events were reported by more than 1 source. The supervision authority assessments showed that 48.3% of the reported cases involved serious errors in the provision of health care, and a system error was the most common cause. We found that supervision authorities investigated significantly more events in small and medium‐sized maternity units than in large units. Eighteen health personnel received reactions; 15 were given a warning, and 3 had their authority limited. We determined that 45.9% of the events were avoidable.

Conclusions

The supervision authorities investigated 1 in 1000 births, mainly in response to complaints issued from patients or relatives. System errors were the most common cause of deficiencies in maternity care.

Keywords: administrative reaction, birth injury, individual error, supervision authority, system error

ABBREVIATIONS

- NPE

Norwegian System of Compensation to Patients (Norsk pasientskadeerstatning)

Key Message

Norwegian supervision authorities investigated 1 in 1000 births, due to adverse events reported mostly by patients or relatives. System errors were the most common cause of deficiencies in obstetric care. Obstetric health personnel seldom received formal administrative reactions.

1. INTRODUCTION

Several international studies have shown that adverse events occur in nearly 10% of hospital admissions, and of these, 40%‐50% could have been prevented.1, 2, 3, 4 In Norway, adverse events occur in 7%‐8% of admissions.5 Few studies have investigated adverse events in maternity units, but 1 study in Spain showed that adverse events were experienced by 3.6% of pregnant women admitted to a hospital.6

Pregnancy and birth seldom have serious outcomes for the mother or infant. Perinatal mortality (infant death after 22 weeks of pregnancy, during birth, or during the first week of life) is low (8 deaths per 1000 births) in European countries.7 Figures from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway showed that perinatal mortality fell from 5.6 to 4.9 per 1000 births during 2009‐2013.8

Maternal mortality is rare in Nordic countries. A recent study estimated 7.2 deaths per 100 000 births.9 In the UK, an estimate of 10 maternal deaths per 100 000 births was reported.10 However, underreporting may occur.

Several EU countries have established reporting systems for adverse events in hospitals. These reporting systems might be organized differently in different countries. The World Health Organization recommended that adverse events should be reported and analyzed to promote learning and prevent similar events. Furthermore, the World Health Organization and the Council of Europe recommended that reporting systems should be free from sanctions.11, 12

Patients and relatives can request a review by the Office of the County Governor (Patients’ and Consumers’ Rights Act, Section 7‐4) to assess whether the health care they received was in accordance with the Norwegian health legislation.13 In general, the same scenario exists in other Nordic countries and in the UK.14

Central issues addressed by the supervision authorities included assessing whether the organization has provided health services in accordance with statutory requirements (system perspective)15 and whether the individual health care worker has provided health care that meets sound professional standards (individual perspective).16 The supervision authorities can conclude that the statutory requirements have not been met (a breach of the law). In that case, there is a clear deviation from sound practice. A case can also be closed after providing advice and guidance, in the absence of a breach of the law. In those cases, conditions in the health service can often be improved. The Norwegian Board of Health Supervision makes all decisions about administrative reactions (warnings, limitations of authority, or loss of authority).

The supervision authorities in Finland (http://www.valvira.fi), the Netherlands (http://www.igj.nl), and the UK (http://www.gmc-uk.org) employ administrative reactions that are equivalent to those employed in Norway. Denmark (http://www.stps.dk) and Sweden (http://www.ivo.se) do not have the category of warnings; instead, they set specific conditions that must be met in the health personnel's professional practice.

Patients and relatives can submit a claim for compensation when an injury results from an error in health care. According to the National Health Service Litigation Authority in the UK, events related to gynecology and obstetrics require the largest amounts of compensation.14 In a publication from the Norwegian System of Compensation to Patients (Norsk pasientskadeerstatning; NPE), fetal asphyxia was the most common reason for compensation, after adverse events related to birth. Nordic studies on claims submitted for compensation have shown that deficiencies in maternity health care are often related to fetal monitoring, routines for calling for help, and delay or lack of operative delivery when indicated.17, 18, 19

In Norway, 32 of 47 maternity units had fewer than 1000 deliveries per year in 2013. Studies from the Nordic countries have shown that more serious events might occur in small maternity units than in large maternity units.20, 21, 22

This study aimed to determine how supervision authorities assessed and resolved cases under review in obstetric care during 2009‐2013. We also examined whether maternity units reported serious incidents, in accordance with the reporting system. We evaluated the distribution of reviewed cases relative to the size of the maternity unit. Finally, we assessed whether the reported adverse events were avoidable.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

It is a statutory requirement in Norway to report to the central authorities serious adverse events that occur in specialized health services.23 Until 1 July 2012, the Specialized Health Services Act, Section 3‐3, mandated that events that resulted in, or could have resulted in, serious injury had to be reported to the Office of the County Governor (previously the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision in the County). The injury was regarded as serious when it had serious consequences on the patient's disease or disorder; or if it caused serious pain or reduced self‐realization in the short or long term. After 1 July 2012, organizations were required to report to the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision any serious adverse events that resulted in death or serious injury, when the result was unexpected, based on the expected risk (Specialized Health Services Act, Section 3‐3a).

For the present study, we collected materials on all cases related to obstetric care that were investigated by the Offices of the County Governors and the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2013. We wrote to the Offices of the County Governors on 27 March 2014 and requested copies of the final letter and documents associated with each case (on average 100 pages per case). The deadline for replying was 25 April 2014. To obtain records from the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision on all investigated cases regarding obstetric care over the same period, we collected data from the electronic archive system, ePhorte. We did not collect any information that had not been collected by the supervision authorities when they were investigating the cases.

We chose to limit the material to adverse events that had led to a serious injury or death. Moreover, we only included adverse events that resulted from treatment provided by the hospital after 22 weeks of pregnancy, during delivery (during birth and 2 hours postpartum), or during the first 6 weeks of life.

We collected information about the maternity units, whether the event happened during pregnancy, delivery, or postpartum, the risk factors, professional expert statements, breaches in the legislation, who reported the event, administrative reactions, the outcomes for the mother and infant, and who investigated the case. Each case was assessed and classified according to the type of error. The maternity units were classified by size: small (< 1000 births per year), medium (≥ 1000 and < 2000 births per year), and large (≥ 2000 births per year).

We assessed whether the death or injury was avoidable (by following clinical guidelines); potentially avoidable (uncertain whether clinical guidelines would have helped); or unavoidable.24, 25, 26

The Norwegian Board of Health Supervision is required to evaluate its own activities regularly.27 This study was designed to fulfill that requirement.

The relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated with chi‐squared tests in spss version 18.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

2.1. Ethical approval

According to a statement from the Regional Ethics Committee, there was no need for an ethical approval to publish the results of an investigation of adverse events by the Norwegian Health Care Supervision Authorities (Reference: REK Sør‐øst 2016/1500B).

3. RESULTS

The Offices of the County Governors investigated 5369 cases of adverse events related to specialized health services during the 5‐year study period. Of these cases, 338 were related to pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum. During the same period, there were 303 034 births.8 An examination of each case showed that 104 (30.8%) involved problems concerning: gynecology, pediatrics, primary health services, intoxicated health personnel, surgery, duty of confidentiality, and other areas. All these cases were excluded from the present study. Another 27 cases (8%) were excluded because no injury to the mother or infant was identified. Therefore, we included 207 cases with a serious outcome.

3.1. Reporting adverse events

Patients or relatives reported 135 adverse events (65.2%), often in cooperation with the Health and Social Services Ombudsman. Maternity units reported 81 (39.1%) serious events, as required by the Specialized Health Services Act, Sections 3‐3, 3‐3a, and 17. Nine (4.3%) adverse events were reported by others (eg, police or lawyers). Eighteen (8.7%) adverse events were reported by more than 1 individual.

3.2. Outcomes for mothers and infants

Among the adverse events, 71 (34.3%) occurred during pregnancy, 144 (69.6%) occurred during delivery, and 42 (20.3%) occurred postpartum. Two or more adverse events occurred in 44 cases.

Eighty‐eight infants died (42.5%). Of these, 34 (16.4%) died before birth, 21 (10.1%) died during delivery, and 33 (15.9%) died postpartum.

Injury was detected in 35 infants (16.9%) postpartum. Forty‐three infants (20.8%) had complications (predominantly hypoxic‐ischemic encephalopathy), which could lead to permanent injury. The causes of infant deaths or injuries were: asphyxia in 93 cases (44.9%), unknown in 22 cases (10.6%), preterm births in 11 cases (5.3%), infection in 7 cases (3.4%), mechanical injury (fracture, plexus) in 7 cases (3.4%), bleeding in 5 cases (2.4%), malformations in 5 cases (2.4%), chronic disease of the mother (diabetes) in 4 cases (1.9%), growth restriction in 4 cases (1.9%), umbilical cord prolapse in 4 cases (1.9%), wrong or no medication when indicated in 3 cases (1.4%), and placental abruption in 2 cases (1.0%).

Five mothers died (2.4%). Of these, 3 died from severe preeclampsia and 2 died from amniotic fluid embolism syndrome. The most common injuries to the mothers were: severe rupture of the birth canal or neighboring organs (n = 14; 6.7%), bleeding (n = 9; 4.3%), mental trauma (inadequate pain control) (n = 7; 3.4%), and other injuries (n = 18; 8.7%). The “other injuries” included: cardiovascular disorders (cardiomyopathy, deep venous thrombosis, cerebral infarction), foreign body retention (forgotten gauze pads), infection, wound rupture, medication error (given the wrong medication), and damage to the central or peripheral nervous system.

3.3. Assessment by supervision authorities

The Offices of the County Governor investigated 163 (78.7%) adverse event cases, and the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision investigated 44 (21.3%) cases. Statements from external professional experts were obtained for 51 (24.6%) cases.

The supervision authorities concluded that a breach of legislation had occurred in 100 cases of adverse events with a serious outcome (48.3%). Thirty‐six cases (17.4%) involved more than 1 breach of legislation.

Among the identified cases with a serious outcome, the following legislative ordinances were breached: the Specialized Health Services Act, Section 2‐2 (the duty of the organization to provide sound health services): 56 cases (27.1%) (Serious system errors); the Health Personnel Act, Section 4 (the duty of health personnel to conduct work in accordance with the requirements of professional responsibility and diligent care): 47 cases (22.7%) (Serious individual errors); the Health Personnel Act, Sections 39 and 40 (the duty to maintain patient records, and requirements for the contents of patient records): 32 cases (15.5%); the duty to report adverse events to the supervision authorities: 10 cases (4.8%); the Health Personnel Act, Section 10 (the duty to give information to patients): 10 cases (4.8%). The supervision authorities provided advice and guidance in 58 cases (28%).

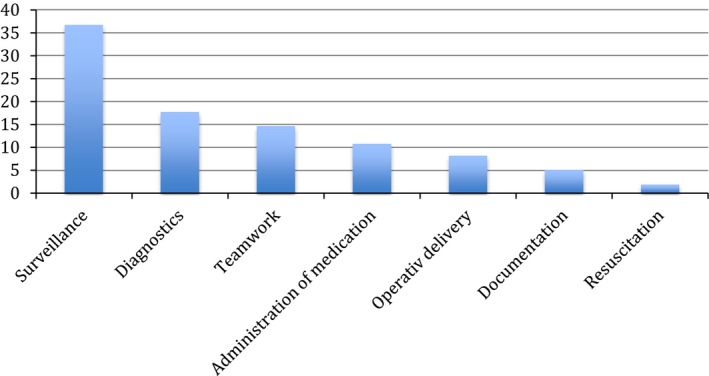

Figure 1 shows that most errors occurred in the categories of surveillance, diagnostics, and teamwork.

Figure 1.

The frequency (%) of health service failure in different categories, among obstetric cases investigated by the Norwegian supervision authorities in 2009‐2013. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

A total of 158 adverse events (76%) involved the failure to provide sound health care. Table 1 shows the numbers of injuries or deaths that occurred due to errors in providing health care, stratified according to the size of the maternity unit. Significantly more adverse event cases occurred in small and medium‐sized maternity units than in large maternity units, demonstrated by the number of events relative to the number of deliveries.

Table 1.

Numbers of deaths or injuries, due to errors in the provision of health care, according to the size of the maternity unit

| <1000 births/year (n = 32) | ≥1000 and <2000 births/year (n = 9) | ≥2000 births/year (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Births 2009‐2013 | 58 331 | 57 176 | 186 925 |

| Death or injury | 61 | 39 | 58 |

| Death or injury/ 1000 births | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 3.4 (2.4‐4.8) | 2.2 (1.5‐3.3) | 1 |

The Norwegian Board of Health Supervision gave warnings to 9 doctors and 6 midwives. Two doctors had their authority limited, due to several adverse event cases. One midwife lost authority, due to physical impairment. Seven of these decisions were appealed by writing to the Norwegian Appeals Board for Health Personnel. One warning was withdrawn. The decision to withdraw the midwife's authority was revised to limited authority.

3.4. Assessments of the present study

We assessed the 207 cases with serious outcomes. We found that, if patient care had been provided differently, 95 errors (45.9%) would have been avoided, and 52 errors (25.1%) could have been potentially avoided. In 60 events (28.9%), the error was unavoidable, according to generally accepted guidelines for treatment.24, 25

4. DISCUSSION

The supervision authorities investigated 338 cases of adverse events that occurred during pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum. The cases were mainly reported by patients or relatives. The most common reason for deficiencies in maternity care was a system error. The supervisory administration rarely reprimanded health professionals.

The supervision authorities assessed relatively few events within this field. The cases identified represented an incidence of 1.1 events per 1000 births. However, an adverse event does not necessarily lead to injury; nevertheless, an error in provision of treatment can be considered serious. In comparison, the NPE receives 1.6 claims for compensation per 1000 births.17 In the UK, the National Health Service Litigation Authority received 1.0 claim for compensation per 1000 births. They interpreted this incidence as an indication that few serious injuries resulted from obstetric care.14

It was surprising that most (65.2%) reports of adverse events sent to the supervision authorities were issued by patients and relatives. Maternity units reported 39.1% of the serious events. The material included in this study consisted of adverse events involving injury or death, which should have been reported to the supervision authorities, in accordance with the Specialized Health Services Act, Sections 3‐3 and 3‐3a. Several potential problems might explain the failure of hospitals to report these events. One problem may be that health personnel lacked knowledge about the reporting system, or they were uncertain about what to report. Another problem may be that health personnel were worried about sanctions. The purpose of the reporting system is to provide the central authorities with an overview of all adverse events that occur; in addition, the reports should be used as part of the hospitals’ efforts to improve the quality of care.

More than three‐quarters of the cases assessed by the supervision authorities involved errors in the provision of health care. Nearly half of the adverse events were serious errors (breaches of the law). This finding indicated that the cases assessed by the supervision authorities are often serious. In comparison, data collected from the NPE regarding obstetric claims showed that 31.9% of the cases resulted in compensation due to errors or omissions in the provision of health care. In those cases, compensation was only awarded on the condition that there was a causal relationship between the error and the injury.17

Among the identified cases involving serious errors in the provision of health care (breaches of the law), 56% were due to system errors (breaches of the Specialized Health Services Act, Section 2‐2). In a similar study on data from the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision for the period 2006‐2008, system errors were found in only 25% of the cases.20 An explanation is that the supervisory authorities now focus more on the underlying causes of failure. The supervisory authorities assess whether a system error occurs by collecting information about routines and practice, organization, responsibility, training, medical equipment, and the staff situation in the department.15 In contrast, the NPE used a different method for assessing cases. They seldom assessed system errors. A publication from the NPE on obstetric care showed that errors were often caused by individuals.17

According to assessments by the supervision authorities, delivering an administrative reaction to health personnel was only considered appropriate or necessary in a few cases, even though individual error was identified in 22.7% of the events. This could be explained by the observation that, often, health personnel realize that they made an error, and therefore, there is no reason for an administrative reaction. This study also revealed that a possible administrative reaction to an individual could be dismissed, when a system error was identified. Therefore, currently, the Swedish and Danish supervision authorities do not give formal warnings; instead, they choose to give critical feedback about the health care that was provided in a given case, or, when appropriate, they limit the authority of the health personnel involved.

We found that, compared with large maternity units, small maternity units had significantly more serious errors in the provision of health care that led to death or injury; this was particularly true in units with fewer than 1000 deliveries per year. The small units may theoretically have a better reporting practice of adverse events, although we have no clear evidence of this. On the other hand, it would be expected that small departments had fewer serious injuries during childbirth, because most of the high‐risk pregnancies are selected for large maternity units. Furthermore, our analyses of these cases showed that there can be challenges associated with running small maternity units, which are absent in large units. For example, small units tend to have a scant permanent staff. There is a constant need to employ temporary staff and some staff members have inadequate skills and qualifications; and they lack routines and multiprofessional simulation training for dealing with acute situations.20, 28, 29

Previous studies have shown that the risk of complications and mortality among women giving birth may be higher in small maternity units than in large maternity units.20, 21, 22, 30 However, the results could be influenced by different definitions of a small maternity unit. The definition of a small maternity unit was fewer than 1000 deliveries per year, in a study from Finland,21 and fewer than 1377 deliveries per year, in a Danish study.22

The strength of this study was that each case had been thoroughly reviewed and evaluated by the supervisory authorities. Their decisions were based on interdisciplinary assessments. A weakness of our study was that it included a relatively small number of incidents.

In this study, we found that 1 in 1000 births in Norway was investigated by the supervision authorities, and that most adverse events were reported by patients and relatives. This finding indicated that hospitals could improve their routines for reporting to the central authorities when an adverse event occurs. According to the assessment of the Norwegian supervision authorities, most adverse events resulted from system errors, not individual errors.

5. CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We hereby state there are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

Johansen LT, Braut GS, Andresen JF, Øian P. An evaluation by the Norwegian Health Care Supervision Authorities of events involving death or injuries in maternity care. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:1206‐1211. 10.1111/aogs.13391

Funding information

No specific funding was obtained.

REFERENCES

- 1. De Vries EN, Ramrattan MA, Smorenburg SM, Gouma DJ, Boermeester MA. The incidence and nature of in‐hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:216‐223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schiøler T, Lipczak H, Pedersen BL, Mogensen TS, Bech KB, Stockmarr A, et al. Incidence of adverse events in hospitals. A retrospective study of medical records. Ugeskr Laeger. 2001;163:5370‐5378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vincent C, Neale G, Woloshynowych M. Adverse events in British hospitals: preliminary retrospective record review. BMJ. 2001;322:517‐519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zegers M, de Bruijne MC, Wagner C, Hoonhout LH, Waaijman R, Smits M, et al. Adverse events and potentially preventable deaths in Dutch hospitals: results of a retrospective patient record review study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:297‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deilkås ET, Bukholm G, Lindstrøm JC, Haugen M. Monitoring adverse events in Norwegian hospitals from 2010 to 2013. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aibar L, Rabanaque MJ, Aibar C, Aranaz JM, Mozas J. Patient safety and adverse events related with obstetric care. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291:825‐830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neonatal and perinatal mortality . World Health Organization. 2004. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43800/1/9789241596145_eng.pdf. Accessed 13 June 2017.

- 8. Norwegian Institute of Public Health . Medisinsk fødselsregister. [Medical Birth Registry of Norway]. In Norwegian. http://statistikk.fhi.no/mfr/. Accessed 10 October 2016.

- 9. Vangen S, Bødker B, Ellingsen L, Saltvedt S, Gissler M, Geirsson R, et al. Maternal deaths in the Nordic countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:1112‐1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. MBRRACE‐UK . Saving lives, Improving Mothers’ Care: lay Summary. 2014. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/downloads/files/mbrrace-uk/reports/Saving%20Lives%20Improving%20Mothers%20Care%20report%202014%20Full.pdf. Accessed 20 February 2017.

- 11. World Health Organization . WHO draft guidelines for adverse events reporting and learning systems. 2005. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/resources/resource/3122. Accessed 13 June 2017.

- 12. Perneger T. The Council of Europe recommendation Rec (2006) 7 on management of patient safety and prevention of adverse events in health care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20:305‐307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lov om statlig tilsyn med helse‐ og omsorgstjenesten m.m (helsetilsynsloven) . [The Act on State Supervision of the Health and Care Services, etc. (Health Supervision Act).] In Norwegian. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1984-03-30-15. Accessed 16 February 2017.

- 14. Ten Years of Maternity Claims – An Analysis of NHS Litigation Authority Data – October 2012.pdf.NHS Litigation Authority. 2013. http://www.nhsla.com/Safety/Documents/Ten. Accessed 13 June 2017.

- 15. Lov om spesialisthelsetjenesten m.m. (spesialisthelsetjenesteloven) § 2‐2. [Act on Specialized Health Services, etc. (Specialized Healthcare Act) § 2‐2.] In Norwegian. 2001. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-61. Accessed 16 February 2017.

- 16. Lov om helsepersonell m.v. (helsepersonelloven) § 4. [Act on Health Personnel etc. (Health Personnel Act) § 4.] In Norwegian. 2001. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-64. Accessed 16 February 2017.

- 17. Andreasen S, Backe B, Jørstad RG, Øian P. A nationwide descriptive study of obstetric claims for compensation in Norway. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91:1191‐1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berglund S, Grunewald C, Pettersson H, Cnattingius S. Severe asphyxia due to delivery‐related malpractice in Sweden 1990‐2005. BJOG. 2008;115:316‐323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hove L, Bock J, Christoffersen JK, Hedegaard M. Analysis of 127 peripartum hypoxic brain injuries from closed claims registered by the Danish Patient Insurance Association. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:72‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johansen LT, Øian P. Barn som dør eller får alvorlig skade under fødsel. [Neonatal death and injuries]. In Norwegian. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2011;131:2465‐2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pyykönen A, Gissler M, Jakobsson M, Petäjä J, Tapper A‐M. Determining obstetric patient safety indicators: the differences in neonatal outcome measures between different‐sized delivery units. BJOG. 2014;121:430‐437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Milland M, Mikkelsen K, Christoffersen J, Hedegaard M. Severe and fatal obstetric injury claims in relation to labor unit volume. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94:534‐541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Spesialisthelsetjenesteloven Kapitel 3.[ Specialized Health Services Act Chapter 3]. In Norwegian. 2001. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-61#KAPITTEL_3. Accessed 16 February 2017.

- 24. Norsk gynekologisk forening. Veileder i fødselshjelp . 2014. [Norwegian Gynecological Association. Guide to childbirth 2014]. (national guidelines in obstetrics). In Norwegian. http://legeforeningen.no/Fagmed/Norsk-gynekologisk-forening/Veiledere/Veileder-i-fodselshjelp-2014/. Accessed 20 June 2017.

- 25. Helsedirektoratet [Directorate of Health]. Et trygt fødetilbud – Kvalitetskrav i fødselsomsorgen [A safe maternity service ‐ quality requirements for maternity care] . 2010. [Norwegian Directorate for Health. A safe food offer—Quality requirements in childcare 2010.] In Norwegian. https://helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/et-trygt-fodetilbud-kvalitetskrav-til-fodselsomsorgen. Accessed 20 June 2017.

- 26. Andersgaard AB, Herbst A, Johansen M, Ivarsson A, Ingemarsson I, Langhoff‐Roos J, et al. Eclampsia in Scandinavia: incidence, substandard care and potentially preventable cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:929‐936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Norwegian Ministry of Finance . Virksomhetens interne styring, kapittel 2. Reglement for økonomistyring i staten, Bestemmelser om økonomistyring i staten, Fastsatt 12. desember 2003 med endringer senest 14. November 2006. [Internal control of enterprises, Chapter 2. Rules for financial management in the state, Provisions on financial management in the state, Established 12 December 2003 with amendments no later than 14 November 2006.] In Norwegian, Oslo: Finansdepartementet, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28. The Norwegian Board of Health Supervision . 2008. Oppsummering av tilsynserfaringer og vurdering av de små fødeavdelingene (enheter med under 500 fødsler per år). [Summary of supervisory experience and assessment of the small maternity departments (units with less than 500 births per year).] In Norwegian. http://www.helsetilsynet.no/no/Publikasjoner/Brev-hoeringsuttalelser/Utvalgte-brev-og-horingsuttalelser-tidligere-ar/Oppsummering-tilsynserfaringer-smaa-foedeavdelingene-under-500-foedsler-aar/. Accessed 26 June 2017.

- 29. Johansen LT, Pay ASD, Broen L, Roland B, Øian P. Are stipulated requirements for the quality of maternity care complied with? Tidskr Nor Legeforen. 2017;137:1299‐1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kyser KL, Lu X, Santillan DA, et al. The association between hospital obstetrical volume and maternal postpartum complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:42.e1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]