Abstract

Approximately 5‐10% of individuals who are vaccinated with a hepatitis B (HB) vaccine designed based on the hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype C fail to acquire protective levels of antibodies. Here, host genetic factors behind low immune response to this HB vaccine were investigated by a genome‐wide association study (GWAS) and Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) association tests. The GWAS and HLA association tests were carried out using a total of 1,193 Japanese individuals including 107 low responders, 351 intermediate responders, and 735 high responders. Classical HLA class II alleles were statistically imputed using the genome‐wide SNP typing data. The GWAS identified independent associations of HLA‐DRB1‐DQB1, HLA‐DPB1 and BTNL2 genes with immune response to a HB vaccine designed based on the HBV genotype C. Five HLA‐DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes and two DPB1 alleles showed significant associations with response to the HB vaccine in a comparison of three groups of 1,193 HB vaccinated individuals. When frequencies of DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes and DPB1 alleles were compared between low immune responders and HBV patients, significant associations were identified for three DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes, and no association was identified for any of the DPB1 alleles. In contrast, no association was identified for DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes and DPB1 alleles in a comparison between high immune responders and healthy individuals. Conclusion: The findings in this study clearly show the importance of HLA‐DR‐DQ (i.e., recognition of a vaccine related HB surface antigen (HBsAg) by specific DR‐DQ haplotypes) and BTNL2 molecules (i.e., high immune response to HB vaccine) for response to a HB vaccine designed based on the HBV genotype C. (Hepatology 2018).

Abbreviations

- CHB

chronic hepatitis B

- GWAS

genome‐wide association study

- HB

hepatitis B

- HBcAb

hepatitis B core antibody

- HBsAb

hepatitis B surface antibody

- HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HLA

Human Leukocyte Antigen

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

Hepatitis B (HB) is one of the most common infectious diseases, with 350 million chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) carriers worldwide. In Japan, an estimated 1.1‐1.4 million individuals (about 1% of the country's population) are infected with HBV; most of these infections were caused by mother‐to‐child transmission before the start of a nationwide HB immunization program initiated by the Japanese government in 1986. About 80% of the HBV‐infected patients in mainland Japan were HBV genotype C.1 Genome‐wide association studies (GWASs) have identified several susceptibility loci with the risk of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection in Asian and Arabian populations, including HLA class II, EHMT2, TCF19, FDX1, HLA‐C, UBE2L3, and VARS2‐SFTA2.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Association tests of HLA class II with CHB infection showed that two HLA‐DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes (i.e., DRB1*15:02‐DQB1*06:01 and DRB1*13:02‐DQB1*06:04) and three DPB1 alleles (i.e., DPB1*02:01, *04:02, and *05:01) were independently associated with CHB infection in the Japanese population.9

Universal HB universal vaccination programs have now implemented in over 180 countries worldwide. In Taiwan, a universal HB vaccination program was launched as early as 1984 to prevent HBV carriage from perinatal mother‐to‐infant infection.10 Although a selective HBV vaccination program continued until 2016 in Japan, the Japanese government started a universal HB vaccination program in October 2016. Several HB vaccines have been developed to prevent HBV infection corresponding to HBV genotypes (i.e., genotype A [Heptavax‐II], genotype A2 [Engerix‐B; Recombivax HB], or genotype C [Bimmugen]). The immune response to HB vaccination differs among individuals, with 5‐10% of healthy individuals failing to acquire protective levels of antibodies. This result suggests the involvement of host genetic factors in the response to vaccination. Indeed, associations of SNPs in HLA class II region with response to HB vaccines have been identified in Asian and European populations.11, 12, 13, 14 In these previous reports, the studied individuals were vaccinated with HB vaccine designed based on the HBV genotype A2. We describe here a GWAS to identify host genetic factors associated with response to a HB vaccine designed based on the HBV genotype C. We know SNP‐based GWAS do not necessarily detect the primary susceptibility locus in the HLA region9; therefore, we carried out association tests of HLA class II alleles in comparisons between HB vaccinated individuals (low responders and high responders), healthy individuals, individuals with spontaneous HBV clearance and HBV patients who carried HBV genotype C, to identify commonality and heterogeneity between these groups.

Participants and Methods

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The University of Tokyo and by all of the following institutes and hospitals throughout Japan that participated in this collaborative study: National Center for Global Health and Medicine; Kawasaki Medical School; University of Tsukuba; Iwate Medical University; and Chiba University. All participants provided written informed consent for participation in this study and the methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Samples and clinical data

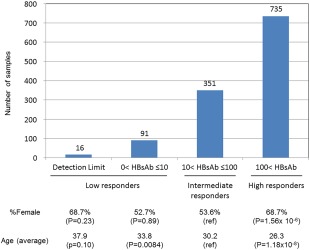

All 1,193 Japanese genomic DNA samples used in this study were obtained from healthy adult volunteers (≥18‐years‐old) who were vaccinated in three doses (0.5 ml) at 0, 1, and 6 months with a recombinant absorbed HB vaccine (Bimmugen, Kaketsuken, Kumamoto, Japan). Individuals who were vaccinated with the Heptavax‐II vaccine (MSD KK, Tokyo, Japan) were not included in this study. Serum anti‐HBV surface antibody (HBsAb) and serum anti‐HBV core antibody (HBcAb) were tested before the vaccination and at 1 month after final inoculation, using the anti‐HBs kit and the anti‐HBc II kit, respectively, with a fully automated chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay system using the Architect i2000SR analyzer (Abbott Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Individuals who were HBcAb‐positive (>1.0 S/CO) were not included in this study. In this study, we categorized 1,193 individuals into three groups: group_0, low responders, HBsAb ≤10 mIU/mL; group_1, intermediate responders, 10 mIU/mL< HBsAb ≤100 mIU/mL; group_2, high responders, HBsAb >100 mIU/mL. The clinical information of 1,193 individuals is summarized for each group in http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo. The distribution of HBsAb levels among the 1,193 Japanese individuals is summarized in Fig. 1. Percentage of female participants and average age between groups were tested using group 1 (intermediate responders) as reference by a chi‐squared test and Welch's t‐test, respectively. Data of age and number of times of past vaccination with Bimmugen were collected from all 1,193 individuals in the writing of the questionnaire. Data of computed gender for the 1,193 individuals were acquired from the genome‐wide SNP genotyping data of the Affymetrix AXIOM genome‐Wide ASI 1 array acquired in this study.

Figure 1.

Distribution of HBsAb levels among 1,193 Japanese individuals. P values were calculated using a chi‐quared test and Welch's t‐test for percentage of female and average age, respectively.

Genome‐wide SNP genotyping and data cleaning

For the GWAS, the 1,193 Japanese genomic DNA samples were genotyped using the Affymetrix Axiom Genome‐Wide ASI 1 Array, according to the manufacturer's instructions. All samples had an overall call rate of more than 96%; the average overall call rate was 99.23% (96.77‐99.88) and passed a heterozygosity check. No related individual (PI ≥0.1) was identified in identity‐by‐descent testing. Principal component analysis was carried out to check the genetic background in the studied 1,193 samples together with HapMap samples (43 JPT, 40 CHB, 91 YRI, and 91 CEU samples). This analysis showed that all 1,193 samples formed the same cluster using the first and second components, indicating that the effect of population stratification was negligible in the studied samples http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo.

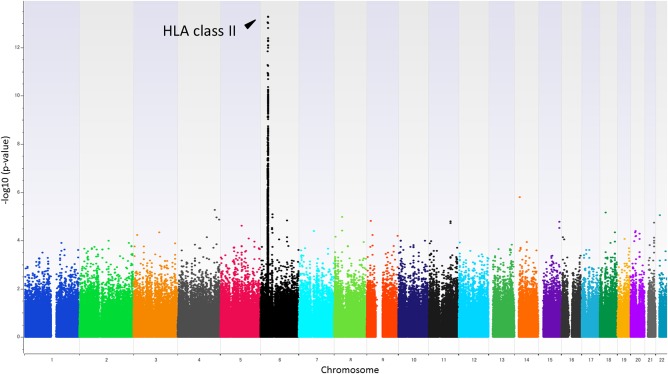

A total of 1,193 individuals were categorized into three groups: group_0, low responders, HBsAb ≤10 mIU/mL (n=107); group_1, intermediate responders, 10 mIU/mL< HBsAb ≤100 mIU/mL (n=351); group_2, high responders, HBsAb >100 mIU/mL (n=735). Genome‐wide multiple regression analysis was carried out using age and sex as covariates, where the above‐mentioned group (i.e., 0, 1, or 2) was used as a dependent variable. The following thresholds were then applied for SNP quality control during the data cleaning: SNP call rate ≥ 95%; minor allele frequency ≥5%; and Hardy‐Weinberg Equilibrium P‐value ≥0.001. All cluster plots for SNPs with a P < 0.0001 based on a chi‐square test of the allele frequency model were checked by visual inspection, and SNPs with ambiguous genotype calls were excluded. Of the SNPs on autosomal chromosomes, 427,664 SNPs finally passed the quality control filters and were used for the association analysis (Fig. 2). To avoid false positives due to multiple testing, the significance levels for α were set at α=0.05/427,664. The 194 SNPs with P < 0.0001 in the GWAS are listed except for the HLA class II region (HLA‐DRA to HLA‐DPA3; Chr6: 32,377,284‐33,099,120) in http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo shows the regional Manhattan plot of the HLA class II region. The 212 SNPs with P < 0.0001 in the GWAS are listed for the HLA class II region in http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo.

Figure 2.

Genome‐wide association results applying a regression analysis with age and sex as covariates. From a total of 1,193 Japanese individuals who received HB vaccination, P values were calculated for 427,664 SNPs by multiple regression analysis in three responder groups (group_0, low responder, HBsAb ≤10; group_1, intermediate responder, 10< HBsAb ≤100; group_2, high responder, HBsAb >100).

HLA imputation

SNP data from 1,193 samples were extracted from an extended MHC (xMHC) region ranging from 25759242 to 33534827 bp based on the hg19 position. We conducted 2‐field HLA genotype imputation for four class II HLA genes using the HIBAG R package.15 For HLA‐DRB1, DQA1, DQB1 and DPB1, our in‐house Japanese imputation reference was used for HLA genotype imputation.16 We applied post‐imputation quality control using call‐threshold (CT >0.5). A total of 1,103 samples showed four estimated HLA genotypes, all of which met the threshold. In total, we imputed 25 HLA‐DRB1, 14 HLA‐DQA1, 14 HLA‐DQB1, and 11 HLA‐DPB1 genotypes for HLA class II genes.

Haplotype estimation

The phased haplotypes consisting of three HLA class II loci (HLA‐DRB1, ‐DQB1, and ‐DPB1) were estimated by using the PHASE program version 2.1.17, 18 The estimated 3‐locus haplotypes were further used for the estimation of haplotypes of HLA‐DRB1 and DQB1 loci (i.e., the collapsing method was applied to the phased data for three HLA loci).

Pairwise linkage disequilibrium between HLA class II alleles

The pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) parameters, r 2 and D′,19 between alleles at different class II HLA loci were calculated based on the haplotype frequencies estimated by using the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm.20 Here, each HLA allele was assumed to be one of the alleles at a bi‐allelic locus, and the other HLA alleles at the same locus were assumed to be the other allele. For example, the DRB1*01:01 allele and the other DRB1 alleles were designated as the “A allele” and the “B allele”, respectively. Accordingly, the EM algorithm for the estimation of haplotype frequencies for two loci each with two alleles could be applied to two HLA alleles at different loci.21

HLA association test

To assess the association of HLA allele or haplotype with response to HB vaccination, P values were calculated using the Cochran‐Armitage trend test in three responder groups (group_0, low responder, HBsAb ≤10; group_1, intermediate responder, 10< HBsAb ≤100; group_2, high responder, HBsAb >100). To avoid false positives due to multiple testing, the significance levels for α were set at α=0.05/50 for beta chain of HLA class II alleles (including DRB1, DQB1, and DPB1), α=0.05/14 for HLA‐DQA1 and α=0.05/31 for HLA DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes.

Web resources

GWAS data in this study will be submitted to the public database “NBDC Human Database” in Japan. The URL for data presented herein is as follows:

NBDC Human Database, https://humandbs.biosciencedbc.jp/en/

Results

All 1,193 Japanese healthy individuals in this study were vaccinated with the same recombinant absorbed HB vaccine, following standard operating procedures (see Participants and Methods for details). Serum and genomic DNA were collected from the 1,193 individuals, and the presence of serum anti‐HBV surface antibody (HBsAb) and serum anti‐HBV core antibody (HBcAb) was then tested at 1 month after the final dose. Because individuals who are HBcAb‐positive are prone to be low responders (HBsAb ≤10 mIU/mL) to HB vaccination, HBcAb‐positive individuals were excluded from this study. In this study, we categorized the 1,193 individuals into three groups: group_0, low responders, HBsAb ≤10 mIU/mL (n=107); group_1, intermediate responders, 10 mIU/mL< HBsAb ≤100 mIU/mL (n=351); and group_2, high responders, HBsAb >100 mIU/mL (n=735). Among the 1,193 samples, 16 individuals who did not reach the detection limit of the HBsAb level were categorized into group_0 (i.e., low responders). A comparison of percentage of female and average age between the three groups indicated that the frequencies of younger individuals and females were significantly increased in high responders (Fig. 1). The significant associations of sex and age with HBsAb levels were also identified by simple linear regression analysis (P = 4.04×10−6 and P = 1.75×10−12, respectively). In contrast, the number of past vaccinations with Bimmugen showed no association in simple linear regression analysis (P = 0.056).

Genome‐wide multiple regression analysis was carried out, in which HBsAb levels were categorized into three groups as a dependent variable, and information of age and sex were used as covariates. The top hit SNP rs2395179 was identified in a HLA class II region, showing P = 5.27×10−14 (Fig. 2). The regional Manhattan plot of a HLA class II region (from HLA‐DRA to HLA‐DPA3; Chr6: 32,377,284‐33,099,120, GRCh37 hg19) showed three peaks (rs2395179 for HLA‐DRA, rs34039593 for HLA‐DRB1, and rs9277549 for HLA‐DPB1) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo. To investigate the relationship between these three variants and HBsAb levels, we performed regression analysis using various combinations of the three associated SNPs as covariates http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo. When the regression analysis was performed using the two SNPs located in the HLA‐DR‐DQ region (i.e., rs2395179 and rs34039593, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo, the associations of a number of other SNPs located around these two SNPs were weakened, whereas those for the SNPs in the HLA‐DP region were not. Similarly, in the regression analysis using rs9277549 located in the HLA‐DP region, associations of surrounding HLA‐DP SNPs weakened, whereas associations for SNPs in HLA‐DR‐DQ region were not weakened http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo. In the regression analysis using the three representative SNPs as covariates, associations of a number of other SNPs located in the HLA class II region were weakened http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo. These results indicated that although SNPs in the HLA class II region were in strong LD with each other, HLA‐DR‐DQ and HLA‐DP regions were independently associated with immune response to the HB vaccine. When a GWAS was carried out using individuals under the age of 30 years, which included 56 low‐responders, 226 intermediate‐responders, and 582 high‐responders, a significant association of SNP in the HLA class II region was identified as similar to the result using a total of 1,193 individuals (rs9268657, P = 4.08×10−9) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo. Among individuals who were categorized into intermediate responders to the HB vaccine, there may exist ambiguous individual(s) who need to be re‐categorized into low or high responders. We therefore carried out a GWAS that compared low responders and high responders, by applying a logistic regression analysis with age and sex as covariates. This GWAS identified a significant association of the BTNL2 gene (rs4248166, P = 5.51×10−12), which is located in a HLA class III gene‐rich region adjacent to a HLA class II region, with response to HB vaccination http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo.

Next, we performed statistical imputation of classical HLA alleles for four HLA loci including HLA‐DRB1, DQA1, DQB1, and DPB1 using 1,193 genome wide SNP typing data as established in our previous report.16 After removing the defect data to compare P values and odds ratios (ORs) of each HLA allele, associations of each HLA allele with HBsAb levels were assessed by calculating P values using the Cochran‐Armitage trend test to test for a trend in the three groups (i.e., group_0 [n=94], group_1 [n=323], and group_2 [n=686]). Significant associations after correction for the total number of the observed alleles (P < 0.05/50) were detected for nine HLA class II alleles (Table 1). The strongest association was observed for HLA‐DRB1*04:05 with a poor response to the HB vaccine (P =2.61×10−9). On the other hand, among HLA class II alleles, HLA‐DPB1*04:02 showed the strongest association with response to the HB vaccine (P =7.58 ×10−8). Because strong LD between DRB1 and DQB1 alleles have been reported in many populations including the Japanese population,22, 23, 24 we then estimated HLA‐DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes in 1,103 studied individuals. This haplotype analysis identified significant associations after correction of the significance level (P < 0.05/31) for a total of five haplotypes (Table 2). Among the estimated haplotypes whose frequency was over 2.0% in the 1,103 studied individuals, two significant DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes, DRB1*04:05‐DQB1*04:01 and DRB1*14:06‐DQB1*03:01, were associated with a poor response to the HB vaccine, and the remaining three significant DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes, DRB1* 01:01‐DQB1*05:01, DRB1*08:03‐DQB1*06:01 and DRB1*15:01‐DQB1*06:02, were associated with response to the HB vaccine.

Table 1.

Associations of HLA class II alleles with response to the HB vaccine

| Allele | p‐valuea |

Frequencies in Group_0 (2n = 188) |

Frequencies in Group_1 (2n = 646) |

Frequencies in Group_2 (2n = 1,372) |

Allele Frequency |

Poor Responder (1) / Responder (0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRB1*01:01 | 8.89E‐05 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 7.1 | 5.6 | 0 |

| DRB1*04:05 | 2.61E‐09 | 28.2 | 17.3 | 12.1 | 15.0 | 1 |

| DRB1*08:03 | 2.75E‐06 | 2.1 | 5.6 | 10.1 | 8.1 | 0 |

| DRB1*09:01 | 0.04748 | 18.1 | 15.5 | 13.3 | 14.4 | 1 |

| DRB1*13:02 | 0.03048 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 7.2 | 6.3 | 0 |

| DRB1*15:01 | 0.0002494 | 1.6 | 6.2 | 8.7 | 7.3 | 0 |

| DRB1*15:02 | 0.1919 | 11.2 | 12.8 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 0 |

| DQB1*03:01 | 0.4503 | 12.8 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 10.6 | 1 |

| DQB1*03:02 | 0.1264 | 10.1 | 10.5 | 8.2 | 9.1 | 0 |

| DQB1*03:03 | 0.1728 | 18.1 | 16.1 | 14.7 | 15.4 | 1 |

| DQB1*04:01 | 5.01E‐09 | 28.2 | 17.5 | 12.3 | 15.2 | 1 |

| DQB1*05:01 | 4.47E‐05 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 7.4 | 5.9 | 0 |

| DQB1*05:03 | 0.3598 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 0 |

| DQB1*06:01 | 0.02667 | 13.3 | 18.4 | 20.3 | 19.1 | 0 |

| DQB1*06:02 | 0.0003225 | 1.6 | 6.0 | 8.5 | 7.2 | 0 |

| DQB1*06:04 | 0.01879 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 0 |

| DPB1*02:01 | 0.05939 | 22.9 | 19.7 | 24.9 | 23.2 | 0 |

| DPB1*03:01 | 0.9037 | 3.7 | 5.9 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 0 |

| DPB1*04:02 | 7.58E‐08 | 1.6 | 6.0 | 11.4 | 9.0 | 0 |

| DPB1*05:01 | 4.76E‐09 | 57.4 | 47.7 | 38.3 | 42.7 | 1 |

| DPB1*09:01 | 0.1832 | 10.6 | 11.8 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 0 |

The allele frequencies over 5.0% in a total of 1,103 Japanese individuals are shown in the table.

P values were calculated using Cochran‐Armitage trend test to test a trend in three groups (group_0, low responder, HBsAb ≤10; group_1, intermediate responder, 10< HBsAb ≤100; group_2, high responder, HBsAb >100). P values, statistically significant after correction of the significance level (P < 0.05/50), are indicated in bold.

Table 2.

Associations of HLA‐DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes with response to the HB vaccine

|

Haplotype (DRB1‐DQB1) |

p‐value |

Frequencies in group_0 (2n = 188) |

Frequencies in Group_1 (2n = 646) |

Frequencies in Group_2 (2n = 1,372) |

Allele Frequency |

Poor Responder (1)/Responder (0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01:01‐05:01 | 8.89E‐05 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 7.1 | 5.6 | 0 |

| 04:03‐03:02 | 0.02484 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 1 |

| 04:05‐04:01 | 2.61E‐09 | 28.2 | 17.3 | 12.1 | 15.0 | 1 |

| 04:06‐03:02 | 0.2962 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 1 |

| 08:02‐03:02 | 0.32 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 0 |

| 08:02‐04:02 | 0.03955 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 0 |

| 08:03‐06:01 | 2.75E‐06 | 2.1 | 5.6 | 10.1 | 8.1 | 0 |

| 09:01‐03:03 | 0.04748 | 18.1 | 15.5 | 13.3 | 14.4 | 1 |

| 11:01‐03:01 | 0.05902 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 0 |

| 12:01‐03:01 | 0.2003 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 0 |

| 13:02‐06:04 | 0.01879 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 0 |

| 14:05‐05:03 | 0.5282 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 1 |

| 14:06‐03:01 | 0.0006397 | 5.3 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1 |

| 14:54‐05:03 | 0.4548 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 0 |

| 15:01‐06:02 | 0.0003225 | 1.6 | 6.0 | 8.5 | 7.2 | 0 |

| 15:02‐06:01 | 0.1919 | 11.2 | 12.8 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 0 |

The estimated haplotype frequencies over 2.0% in a total of 1,103 Japanese individuals are shown in the table.

*P values were calculated using Cochran‐Armitage trend test to test a trend in three groups (group_0, low responder, HBsAb ≤10; group_1, intermediate responder, 10< HBsAb ≤100; group_2, high responder, HBsAb >100). P values, statistically significant after correction of the significance level (P < 0.05/31), are indicated in bold.

Frequencies of HLA‐DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes and HLA‐DPB1 alleles were then compared between HB vaccinated individuals and HBV patients described in our previous report.9 Here, the associations of HLA class II genes with chronic HBV infection were recalculated, because HLA imputation was carried out again using our in‐house Japanese imputation reference http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo. In a comparison between low responders to the HB vaccine and HBV patients, three DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes, DRB1*04:05‐DQB1*04:01, DRB1*08:03‐DQB1*06:01 and DRB1*14:06‐DQB1*03:01, showed significant associations, while no association of DPB1 alleles was identified (Table 3). There was no significant association of any haplotype or allele in a comparison between high responders to HB vaccine and healthy individuals http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo. Moreover, frequencies of HLA‐DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes and DPB1 alleles were compared between low responders to the HB vaccine and spontaneous HBV clearance individuals described in our previous paper.4 A similar result was obtained, as shown in the comparison between low responders and high responders, because frequencies of HLA alleles showed very similar both in spontaneous HBV clearance individuals and high responders http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo.

Table 3.

Comparison of DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes and DPB1 alleles between low responders to the HB vaccine and HBV patients

| Group_0 | HBV Patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2n = 188) | (2n = 1,630) | 95% CI | ||||||

| Allele/Haplotype | count | % | count | % | P‐value | OR | Lower | Upper |

| DRB1*01:01‐DQB1*05:01 | 3 | 1.6 | 44 | 2.7 | 3.67E‐01 | 0.58 | 0.18 | 1.90 |

| DRB1*04:03‐DQB1*03:02 | 8 | 4.3 | 24 | 1.5 | 6.00E‐03 | 2.97 | 1.32 | 6.72 |

| DRB1*04:05‐DQB1*04:01 | 53 | 28.2 | 212 | 13.0 | 2.31E‐08 | 2.63 | 1.85 | 3.72 |

| DRB1*04:06‐DQB1*03:02 | 8 | 4.3 | 28 | 1.7 | 1.80E‐02 | 2.54 | 1.14 | 5.66 |

| DRB1*04:10‐DQB1*04:02 | 3 | 1.6 | 22 | 1.3 | 7.84E‐01 | 1.19 | 0.35 | 4.00 |

| DRB1*08:03‐DQB1*06:01 | 4 | 2.1 | 179 | 11.0 | 1.33E‐04 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.48 |

| DRB1*09:01‐DQB1*03:03 | 34 | 18.1 | 306 | 18.8 | 8.19E‐01 | 0.96 | 0.65 | 1.41 |

| DRB1*13:02‐DQB1*06:04 | 7 | 3.7 | 37 | 2.3 | 2.19E‐01 | 1.67 | 0.73 | 3.79 |

| DRB1*14:03‐DQB1*03:01 | 5 | 2.7 | 9 | 0.6 | 1.75E‐03 | 4.92 | 1.63 | 14.84 |

| DRB1*14:05‐DQB1*05:03 | 5 | 2.7 | 33 | 2.0 | 5.64E‐01 | 1.32 | 0.51 | 3.43 |

| DRB1*14:06‐DQB1*03:01 | 10 | 5.3 | 2 | 0.1 | 7.98E‐17 | 45.73 | 9.94 | 210.36 |

| DRB1*14:54‐DQB1*05:03 | 5 | 2.7 | 30 | 1.8 | 4.39E‐01 | 1.46 | 0.56 | 3.80 |

| DRB1*15:01‐DQB1*06:02 | 3 | 1.6 | 113 | 6.9 | 4.58E‐03 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.69 |

| DRB1*15:02‐DQB1*06:01 | 21 | 11.2 | 306 | 18.8 | 1.02E‐02 | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.87 |

| DPB1*02:01 | 43 | 22.9 | 301 | 18.5 | 1.44E‐01 | 1.31 | 0.91 | 1.88 |

| DPB1*03:01 | 7 | 3.7 | 85 | 5.2 | 3.77E‐01 | 0.70 | 0.32 | 1.54 |

| DPB1*04:01 | 2 | 1.1 | 36 | 2.2 | 2.99E‐01 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 1.99 |

| DPB1*04:02 | 3 | 1.6 | 89 | 5.5 | 2.21E‐02 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.90 |

| DPB1*05:01 | 108 | 57.4 | 756 | 46.4 | 4.01E‐03 | 1.56 | 1.15 | 2.12 |

| DPB1*09:01 | 20 | 10.6 | 266 | 16.3 | 4.28E‐02 | 0.61 | 0.38 | 0.99 |

| DPB1*13:01 | 3 | 1.6 | 28 | 1.7 | 9.03E‐01 | 0.93 | 0.28 | 3.08 |

The estimated DRB1‐DQB1 haplotype frequencies over 1.5%, and DPB1 allele frequencies over 1.0% in 94 HB vaccine low responders (group_0) are shown in the table. Significance level (α) was adjusted based on the number of observed haplotypes and alleles at each locus. Significance levels for DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes and DPB1 alleles were set at α = 0.05/31 and 0.05/50, respectively. P value and odd ratio (OR) were calculated by Pearson's chi‐square test in presence vs. absence of each allele. P values and OR, statistically significant after correction of the significance level, are indicated in bold.

In general, the beta chain of HLA class II molecule shows higher level of polymorphism than the alpha chain and is considered to be better marker for risk prediction. Moreover, it is possible to estimate the DRA1/DQA1 allele from the DRB1/DQB1 allele because a strong LD exists between DRA1/DQA1 and DRB1/DQB1 loci. Here, we carried out HLA imputation for HLA‐DQA1. In the comparison of HLA‐DQA1 frequencies between low responders and high responders, three DQA1 alleles showed significant associations after correction for the total number of the observed alleles (P < 0.05/14) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo.

Discussion

Among a total of 1,193 studied individuals who were vaccinated with a HB vaccine designed based on HBV genotype C (i.e., Bimmugen), 107 individuals (8.9%) showed a low response to this HB vaccine (HBsAb ≤10 mIU/mL). The distribution of low responders in the studied individuals is in concordance with past empirical data, with 5‐10% of healthy individuals failing to acquire protective levels of antibodies. Although there has been a report of a HBV‐vaccinated donor showing a HBsAb value of 96 IU per liter who was found to be positive for HBV DNA,25 we set levels of antibodies against HBV surface antigen as 10 IU per liter or more to be considered as having immunity against HBV, following the World Health Organization recommendation. In this study, we categorized 1,193 individuals into three groups of vaccine responders and identified that the frequencies of younger individuals and females were significantly increased in high responders.

Significant associations of SNPs located in the HLA class II region with vaccine response were identified in a genome‐wide multiple regression analysis using age and sex as covariates. Moreover, HLA‐DRB1‐DQB1 and DPB1 regions showed independent associations with response to the HB vaccine when regression analysis was applied using three variants (rs2395179 for HLA‐DRA, rs34039593 for HLA‐DRB1, and rs9277549 for HLA‐DPB1) as covariates. There was a total of 194 SNPs outside and 212 SNPs inside the HLA class II region that had a P value lower than 0.0001 in the GWAS. Among these 194 SNPs, SNPs located in the BTNL2 gene showed a significant association with response to HB vaccination (rs4248166, P=1.49×10−12). Regression analysis in which the three SNPs (rs2395179, rs34039593, and rs9277549) were applied as covariates showed that a BTNL2 SNP (rs4248166) was independently associated with a response to HB vaccine (P=0.006). This is the same SNP (rs4248166) that was significantly identified in the GWAS in which regression analysis was applied with age and sex as covariates, in a comparison between 107 low responders and 735 high responders (OR=0.20, P = 5.51×10−12). In previous GWASs in Indonesian and Chinese populations,11, 13 associations of SNPs located in HLA‐DRB1 and BTNL2 genes with response to a HB vaccine designed based on the HBV genotype A2 were identified. Because the current HBV‐A2 vaccines are known to have cross‐reactivity with, and confer cross‐protection against non‐A2 HBV genotypes,26 genetic backgrounds behind response to the HBV‐A2 and the HBV‐C vaccines may be very similar.

The BTNL2 gene has been reported to have an important function in the regulation of T cell activation,27 which has implications for a variety of immune diseases, such as sarcoidosis28 and inflammatory bowel disease,29 as well as for immunotherapy.30 Moreover, the resolution of woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) infection was reported to be accompanied by high level expression of inhibitory T cell receptors PD‐1 (PDCD1) and BTNL2.31 WHV was the first of the mammalian and avian hepadnaviruses described after discovery of the HBV, and known to develop progressively severe hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. An SNP rs9277534 in the 3′ UTR region of HLA‐DPB1, which showed a strong LD (r2=0.99) with rs9277535 in the Japanese individuals, was reported to be associated with HBV recovery in both European‐ and African‐American populations.32 Moreover, the GG genotype at rs9277534 was revealed to be associated with higher levels of HLA‐DP surface protein and transcript expression in European‐ and African‐American cohort.32 These observations designate the importance of functional analysis of HLA expression level in hepatocytes in the Japanese population. The DPB1*04:02 and DPB1*05:01 alleles, which showed the higher and lower response to the HB vaccine in this study, have A and G nucleotides at rs9277534, respectively. Although the possible contribution of HLA‐DP expression levels on response to the HB vaccine needs further investigation on the other DP alleles in the Japanese population, the expression level could also affect the response to the HB vaccine. These results imply that both recognition of HBV surface antigens (HBsAg) by HLA class II molecules and regulation of T cell activation by BTNL2 molecules are key mechanisms for response to a HB vaccine.

Here, functional variant(s) located in HLA class II and BTNL2 genes were predicted using the bioinformatic tool SNP Function Prediction (FuncPred; http://snpinfo.niehs.nih.gov/cgi-bin/snpinfo/snpfunc.cgi) and the database GTEx portal (http://gtexportal.org/home/). Two hundred ten and 58 SNPs, having LD >0.2 with rs2395179 (top hit SNP in HLA class II) and rs4248166 (top hit SNP in BTNL2) in the Japanese population, respectively, were selected. SNP function predictions were then carried out including nonsynonymous SNP (nsSNP), splicing regulation, stop codon, polyphen prediction, SNPs3D prediction, TFBS prediction, miRNA binding site prediction, regulatory potential score, conservation score, and nearby genes. Six SNPs for HLA class II gene and 11 SNPs for BTNL2 gene were finally selected to be predicted as transcription binding site(s) or nsSNP http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo. All six SNPs for HLA class II and 10 out of 11 SNPs for BTNL2 showed a significant association with HLA‐DRB1 mRNA expression in both whole blood and lung http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo, and with BTNL2 mRNA expression in small intestine http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo.

To further understand the association of HLA class II genes with response to the HB vaccine, we carried out HLA association tests by applying statistical imputation of HLA alleles using genome‐wide SNP typing data. Nine HLA class II alleles showed significant associations with response to the HB vaccine; three of these alleles were associated with a poor response, and the remaining six were associated with response to the HB vaccine. Among these nine HLA class II alleles, the association of DQB1*04:01 with non‐responsiveness to the HBsAg,33 and the association of five other alleles with vaccine response (DRB1*01:01, DRB1*08:03, DQB1*05:01, and DPB1*04:02 with sufficient response to the HB vaccine and DPB1*05:01 with a poor response to the HB vaccine)34 were clearly replicated the results of previous studies in the Japanese population. Here, an epitope prediction for the nine associated HLA class II alleles was carried out using the immune epitope database (IEDB) 3.0, showing predicted core peptides within vaccinated HBsAg region for each HLA allele http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for the predicted core peptide showed smaller in HLA‐DQ and DP allele products which were associated with responder than the ones which are associated with poor responder. In this study, we carried out haplotype analysis for HLA‐DRB1 and DQB1 loci, and then associations with vaccine response were analyzed using the Cochran‐Armitage trend test to test for a trend in three responder groups. Five HLA‐DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes showed significant associations with response to the HB vaccine. When frequencies of DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes and DPB1 alleles were compared between low responders to the HB vaccine and HBV patients, three out of the five DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes showed a significant association; however, no association was observed for HLA‐DPB1 alleles. These three DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes may specifically recognize a HBsAg peptide derived from the HB vaccine, which might then lead to activation of humoral immune responses. The remaining two DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes and DPB1 alleles may have an important role in the development of chronic HBV infection via cellular immune responses against the HBsAg, although one of the remaining two DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes, DRB1*15:01‐DQB1*06:02, showed a borderline association in the comparison. Two associated HLA‐DPB1 alleles, DPB1*04:02 (high response to HB vaccine) and *05:01 (low response to HB vaccine), indeed showed to be protective against and susceptible to CHB infection, respectively.

On the other hand, in a comparison of frequencies of DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes and DPB1 alleles between high responders to the HB vaccine, and both healthy individuals and spontaneous HBV clearance individuals, no association with vaccine response was identified. This result indicated that HLA class II genes have no association with high response to the HB vaccine (i.e., HBsAb >100 mIU/mL). Together with the fact that the BTNL2 gene showed a significant association in the comparison between high responders and low responders to the HB vaccine, the BTNL2 gene may have T cell or B cell mediated functions for high response to the HB vaccine.

Table 4 summarizes associations of genes and alleles with response to the HB vaccine, CHB infection and spontaneous HBV clearance. The findings in this study clearly show the importance of HLA‐DRB1‐DQB1 haplotypes (i.e. recognition of a HB vaccine related HBsAg by specific DR‐DQ haplotypes) and BTNL2 molecules (i.e., high immune response to the HB vaccine) for response to a HB vaccine designed based on the HBV genotype C. The future functional analysis including analysis of specific binding interactions between HLA class II molecules and HBsAg peptides, HLA expression in human hepatocytes, T helper cell responses to HB vaccination, and HBsAb production in specific‐HLA expressing cells, may lead to clarification of the mechanism behind the development of chronic HBV infection.

Table 4.

Associations of genes and alleles with response to HB vaccine, CHB infection and spontaneous HBV clearance.

| Response to HB vaccinea | HLA‐DRB1/‐DQB1/‐DPB1 | DPB1*04:02 |

| DPB1*05:01 | ||

| DRB1*01:01‐DQB1*05:01 | ||

| DRB1*04:05‐DQB1*04:01 | ||

| DRB1*08:03‐DQB1*06:01 | ||

| DRB1*14:06‐DQB1*03:01 | ||

| DRB1*15:01‐DQB1*06:02 | ||

| BTNL2 | rs4248166 C/T | |

| Chronic hepatitis B infection | HLA‐DRB1/‐DQB1/‐DPB1 b | DPB1*02:01 |

| DPB1*04:01 | ||

| DPB1*05:01 | ||

| DRB1*15:02‐DQB1*06:01 | ||

| DRB1*13:02‐DQB1*06:04 | ||

| HLA‐DPA1/‐DPB1 c | rs3077 C/T | |

| rs9277535 A/G | ||

| Spontaneous HBV clearance | HLA‐DPA1/‐DPB1 c | rs3077 C/T |

| rs9277535 A/G | ||

| HLA‐DPB1 d | rs9277534 A/G |

Author names in bold designate shared co‐first authorship.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo.

Supporting Information 1

Acknowledgment

We thank contributors for their technical assistance including Ms. Yuka Oeda, Ms. Mayumi Ishii, and Ms. Yoriko Mawatari (The National Center for Global Health and Medicine), and Dr. Minae Kawashima, Ms. Megumi Yamaoka‐Sageshima, Ms. Yuko Ogasawara‐Hirano, Ms. Natsumi Baba, Ms. Rieko Shirahashi, Ms. Ayumi Nakayama, Ms. Kayoko Yamada, and Ms. Kayoko Kato (The University of Tokyo).

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Supported by Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science(16K09387) to N.N.; Research Program on Hepatitis from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (H26‐kanenjitsu‐kanen‐ippan‐004and 16fk021010h0001) to K.T. and N.N., (JP16kk0205007) to M.M., M.S., K.T., and N.N., (JP17fk0310115) to N.N. and J.O., (JP17fk0210302) to M.M. and (JP16km0405205) to K.T.; and by a Grant from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (28‐shi‐1302) to N.N. and J.O., (26‐shi‐108) to M.S., and (28‐shi‐001) to M.M.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ito K, Yotsuyanagi H, Sugiyama M, Yatsuhashi H, Karino Y, Takikawa Y, et al. Geographic distribution and characteristics of genotype A hepatitis B virus infection in acute and chronic hepatitis B patients in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31:180‐189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kamatani Y, Wattanapokayakit S, Ochi H, Kawaguchi T, Takahashi A, Hosono N, et al. A genome‐wide association study identifies variants in the HLA‐DP locus associated with chronic hepatitis B in Asians. Nat Genet 2009;41:591‐595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mbarek H, Ochi H, Urabe Y, Kumar V, Kubo M, Hosono N, et al. A genome‐wide association study of chronic hepatitis B identified novel risk locus in a Japanese population. Hum Mol Genet 2011;20:3884‐3892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nishida N, Sawai H, Matsuura K, Sugiyama M, Ahn SH, Park JY, et al. Genome‐wide association study confirming association of HLA‐DP with protection against chronic hepatitis B and viral clearance in Japanese and Korean. PLoS One 2012;7:e39175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim YJ, Kim HY, Lee JH, Yu SJ, Yoon JH, Lee HS, Kim CY, et al. A genome‐wide association study identified new variants associated with the risk of chronic hepatitis B. Hum Mol Genet 2013;22:4233‐4238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Al‐Qahtani A, Khalak HG, Alkuraya FS, Al‐hamoudi W, Alswat K, Al Balwi MA, et al. Genome‐wide association study of chronic hepatitis B virus infection reveals a novel candidate risk allele on 11q22.3. J Med Genet 2013;50:725‐732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hu Z, Liu Y, Zhai X, Dai J, Jin G, Wang L, et al. New loci associated with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Han Chinese. Nat Genet 2013;45:1499‐1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheong HS, Lee JH, Yu SJ, Yoon JH, Lee HS, Cheong JY, et al. Association of VARS2‐SFTA2 polymorphisms with the risk of chronic hepatitis B in a Korean population. Liver Int 2015;35:1934‐1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nishida N, Ohashi J, Khor SS, Sugiyama M, Tsuchiura T, Sawai H, et al. Understanding of HLA‐conferred susceptibility to chronic hepatitis B infection requires HLA genotyping‐based association analysis. Sci Rep 2016;6:24767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen DS, Hsu NH, Sung JL, Hsu TC, Hsu ST, Kuo YT, et al. A mass vaccination program in Taiwan against hepatitis B virus infection in infants of hepatitis B surface antigen‐carrier mothers. JAMA 1987;257:2597‐2603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Png E, Thalamuthu A, Ong RT, Snippe H, Boland GJ, Seielstad M. A genome‐wide association study of hepatitis B vaccine response in an Indonesian population reveals multiple independent risk variants in the HLA region. Hum Mol Genet 2011;20:3893‐3898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yucesoy B, Talzhanov Y, Johnson VJ, Wilson NW, Biagini RE, Wang W, et al. Genetic variants within the MHC region are associated with immune responsiveness to childhood vaccinations. Vaccine 2013;31:5381‐5391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pan L, Zhang L, Zhang W, Wu X, Li Y, Yan B, et al. A genome‐wide association study identifies polymorphisms in the HLA‐DR region associated with non‐response to hepatitis B vaccination in Chinese Han populations. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:2210‐2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roh EY, Yoon JH, In JW, Lee N, Shin S, Song EY. Association of HLA‐DP variants with the responsiveness to Hepatitis B virus vaccination in Korean Infants. Vaccine 2016;34:2602‐2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zheng X, Shen J, Cox C, Wakefield JC, Ehm MG, Nelson MR, et al. HIBAG‐‐HLA genotype imputation with attribute bagging. Pharmacogenomics J 2014;14:192‐200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khor SS, Yang W, Kawashima M, Kamitsuji S, Zheng X, Nishida N, et al. High‐accuracy imputation for HLA class I and II genes based on high‐resolution SNP data of population‐specific references. Pharmacogenomics J 2015;15:530‐537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stephens M, Scheet P. Accounting for decay of linkage disequilibrium in haplotype inference and missing‐data imputation. Am J Hum Genet 2005;76:449‐462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from popuelation data. Am J Hum Genet 2001;68:978‐989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lewontin RC. The Interaction of Selection and Linkage. I. General Considerations; Heterotic Models. Genetics 1964;49:49‐67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Excoffier L, Slatkin M. Maximum‐likelihood estimation of molecular haplotype frequencies in a diploid population. Mol Biol Evol 1995;12:921‐927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kawashima M, Ohashi J, Nishida N, Tokunaga K. Evolutionary analysis of classical HLA class I and II genes suggests that recent positive selection acted on DPB1*04:01 in Japanese population. PLoS One 2012;7:e46806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trachtenberg EA, Erlich HA, Rickards O, DeStefano GF, Klitz W. HLA class II linkage disequilibrium and haplotype evolution in the Cayapa Indians of Ecuador. Am J Hum Genet 1995;57:415‐424. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ronningen KS, Spurkland A, Markussen G, Iwe T, Vartdal F, Thorsby E. Distribution of HLA class II alleles among Norwegian Caucasians. Hum Immunol 1990;29:275‐281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tokunaga K, Ishikawa Y, Ogawa A, Wang H, Mitsunaga S, Moriyama S, et al. Sequence‐based association analysis of HLA class I and II alleles in Japanese supports conservation of common haplotypes. Immunogenetics 1997;46:199‐205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stramer SL, Wend U, Candotti D, Foster GA, Hollinger FB, Dodd RY, Allain JP, et al. Nucleic acid testing to detect HBV infection in blood donors. N Engl J Med 2011;364:236‐247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cassidy A, Mossman S, Olivieri A, De Ridder M, Leroux‐Roels G. Hepatitis B vaccine effectiveness in the face of global HBV genotype diversity. Expert Rev Vaccines 2011;10:1709‐1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nguyen T, Liu XK, Zhang Y, Dong C. BTNL2, a butyrophilin‐like molecule that functions to inhibit T cell activation. J Immunol 2006;176:7354‐7360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Valentonyte R, Hampe J, Huse K, Rosenstiel P, Albrecht M, Stenzel A, et al. Sarcoidosis is associated with a truncating splice site mutation in BTNL2. Nat Genet 2005;37:357‐364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prescott NJ, Lehne B, Stone K, Lee JC, Taylor K, Knight J, et al. Pooled sequencing of 531 genes in inflammatory bowel disease identifies an associated rare variant in BTNL2 and implicates other immune related genes. PLoS Genet 2015;11:e1004955. Erratum in PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arnett HA, Viney JL. Immune modulation by butyrophilins. Nat Rev Immunol 2014;14:559‐569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fletcher SP, Chin DJ, Cheng DT, Ravindran P, Bitter H, Gruenbaum L, et al. Identification of an intrahepatic transcriptional signature associated with self‐limiting infection in the woodchuck model of hepatitis B. Hepatology 2013;57:13‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomas R, Thio CL, Apps R, Qi Y, Gao X, Marti D, et al. A novel variant marking HLA‐DP expression levels predicts recovery from hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol 2012;86:6979‐6985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hatae K, Kimura A, Okubo R, Watanabe H, Erlich HA, Ueda K, et al. Genetic control of nonresponsiveness to hepatitis B virus vaccine by an extended HLA haplotype. Eur J Immunol 1992;22:1899‐1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sakai A, Noguchi E, Fukushima T, Tagawa M, Iwabuchi A, Kita M, et al. Identification of amino acids in antigen‐binding site of class II HLA proteins independently associated with hepatitis B vaccine response. Vaccine 2017;35:703‐710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional supporting information may be found at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29876/suppinfo.

Supporting Information 1