Abstract

Objectives

In published clinical and autobiographical accounts of eating disorders, patients often describe their disorder in personified ways, that is, relating to the disorder as if it were an entity, and treatment often involves techniques of externalization. By encouraging patients to think about their eating disorder as a relationship, this study aimed to examine how young female patients experience their eating disorder as acting towards them, how they react in response, and whether these interactions are associated with symptoms, illness duration, and self‐image.

Design

Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB) was used to operationalize how patients experience the actions of their eating disorder and their own reactions to the disorder.

Method

The relationship between patients (N = 150) and their eating disorders was examined with respect to symptoms, duration of illness, and self‐image. Patients were also compared on their tendency to react with affiliation in relation to their disorder.

Results

Patients’ responses on the SASB indicated that they tended to conceptualize their eating disorders as blaming and controlling, and they themselves as sulking and submitting in response. Greater experience of the eating disorder as being controlling was associated with higher levels of symptomatology. Patients reacting with more negative affiliation towards their disorder were less symptomatic.

Conclusions

When encouraging patients to think about their eating disorder as a relationship, comprehensible relationship patterns between patients and their eating disorders emerged. The idea that this alleged relationship may resemble a real‐life relationship could have theoretical implications, and its exploration may be of interest in treatment.

Practitioner points

Patients were able to conceptualize their eating disorder as a significant other to whom they relate when encouraged to do so.

Patients tended to experience their disorder as controlling and domineering.

Exploring the hypothetical patient–eating disorder relationship may prove helpful in understanding dysfunctional relational patterns.

Helping patients to rebel against their eating disorder could potentially aid in symptom reduction.

Keywords: control, eating disorders, intrapersonal relationship, self‐image, submission

Background

Eating disorders are complex and potentially life‐threatening conditions (Fairburn & Harrison, 2003), and many patients with eating disorders experience long duration of illness before entering treatment (af Sandeberg et al., 2009). Once in treatment, many are reluctant about change (Abbate‐Daga, Amianto, Delsedime, De‐Bacco, & Fassino, 2013; Halmi, 2013), dropout (Fassino, Piero, Tomba, & Abbate‐Daga, 2009), or relapse (Norring & Sohlberg, 1993). Given these challenges, it is important to understand underlying psychological mechanisms better.

In qualitative studies of eating disorders, patients often describe their illness as an entity or voice that they actively relate to (Tierney & Fox, 2011). This voice may be experienced as acting independently of the patient, while at the same time exerting a high degree of influence (Pugh & Waller, 2016a; Tierney & Fox, 2010). Early in the illness, the voice may be experienced as positive, encouraging efforts to lose weight and change body shape, while at the same time providing confidence and a sense of control (Serpell, Treasure, Teasdale, & Sullivan, 1999; Williams & Reid, 2012). As the illness progresses however, patients report that their disorder becomes tyrannical, criticizing and dominating, taking priority over other relationships, and resulting in social isolation (Serpell & Treasure, 2002; Serpell et al., 1999). In anorexia nervosa, descriptions like these are especially frequent and commonly referred to as the ‘anorexic voice’ (Pugh & Waller, 2016a,b; Tierney & Fox, 2010, 2011; Williams & Reid, 2012). Living with the anorexic voice has parallels to living in an abusive relationship due to its coercive nature and impact on self‐esteem (Tierney & Fox, 2011). Patients seem to feel affiliation towards the voice in spite of its negative attributes (Tierney & Fox, 2010). A more powerful and malevolent voice seems associated with lower BMI (Pugh & Waller, 2016a), longer duration of illness, and more severe and enduring forms of anorexia nervosa (Pugh & Waller, 2016b), while learning to defend against the voice appears important for recovery (Duncan, Sebar, & Lee, 2015). Descriptions of eating disorders as personified others are reported by patients with other eating disorder diagnoses as well (Serpell & Treasure, 2002; Serpell et al., 1999), but much less is known about these groups. In one quantitative study, Noordenbos, Aliakbari, and Campbell (2014) found that patients with eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and eating disorder not otherwise specified) experienced critical inner voices significantly more often than controls, that voice frequency and malevolence were positively associated with self‐criticism, and that this had consequences for self‐esteem.

Some forms of treatment (e.g., narrative therapy and the evidence‐based Maudsley family therapy) use externalization of the eating disorder as an integral therapeutic component. It is assumed to aid recovery by helping patients gain a critical onlooker stance and observe their disorder objectively (Scott, Hanstock, & Patterson‐Kane, 2013). Others have criticized this practice, arguing that there is a risk of patients denying their responsibility and that the phenomenon is constructed by therapists, not patients (Pugh, 2016).

Conceptualizing this phenomenon as an intrapersonal relationship, that is, considering both how the eating disorder is experienced as acting and how the patient responds to such actions, could offer novel insights. It assumes that both relational partners play a part, and avoids annulling the patient's responsibility. Interpersonal theory (Sullivan, 1953) may be helpful in such a conceptualization by contributing insight into why the voice of the illness impacts self‐esteem and self‐criticism. According to interpersonal theory, one's self‐image is formed in relationships with significant others; that is, ‘I treat myself the way important others have treated me’. There are strong associations between self‐treatment (self‐image) and eating disorder symptoms (Forsén Mantilla & Birgegård, 2015). Thus, in eating disorders the sphere of significant relationships may also include the disorder itself, representing an internalized, intrapersonal entity that the patient possibly relates to as if it were a significant other, with implications for self‐image. Further, in line with research on the anorexic voice, how the eating disorder is experienced as acting might have implications for symptoms and illness duration, although we cannot be certain that this is the case for patients with other eating disorder diagnoses. How patients in turn respond to their illnesses’ actions might also be associated with these variables, but patients’ responses to their eating disorders’ actions have not been systematically studied previously. For example, defending against the voice may induce cognitive dissonance: a mismatch between beliefs (e.g., ‘my eating disorder protects me’) and behaviour (e.g., writing a warning letter about the eating disorder to a younger self) that may help patients to extricate themselves from its influence.

This study examined how female1 patients with eating disorder (diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or eating disorder not otherwise specified) experience their disorder as acting towards them and how they react in response, before entering specialist treatment (i.e., before being influenced by potential externalizing exercises in treatment). As this hypothetical relationship has not been investigated in different diagnostic groups before, the first aim of the study was to examine diagnostic differences in how the eating disorder was perceived as acting and in how patients reacted in response. As illness duration and specific eating disorder symptoms could potentially be associated with certain relationship patterns (e.g., restricting food intake reflecting eating disorder control and patient submission), the study's second aim was to examine associations between eating disorder actions and patients’ reactions on the one hand and eating disorder symptoms and duration of illness on the other. The third aim was to examine the degree of dissonance within the alleged patient–eating disorder relationship, that is, the mismatch between eating disorder actions and patients’ reactions in terms of relative strength of interpersonal behaviours within the relationship, and its potential impact on symptoms, illness duration, and self‐image.

Method

Participants

Participants were 16‐ to 25‐year‐old (M = 20.5; SD = 2.7) females with a DSM‐IV eating disorder diagnosis and no previous specialist eating disorder treatment who were being treated at one of five specialized eating disorder units for outpatient treatment in Sweden. Data were collected via Stepwise, a large‐scale clinical data collection system (Birgegård, Björck, & Clinton, 2010), and via additional questionnaires sent out to participants. Over the course of data collection (March 2014–2016), 508 female patients were eligible for the study and were asked to participate. Of these, 46% never responded, and of those who did, 27% failed to return their forms. Excluding those who declined to participate, submitted incomplete forms, or had been in treatment previously this resulted in 150 patients (anorexia nervosa, n = 55, 37%; bulimia nervosa, n = 33, 22%; and eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS), n = 62, 41%). The sample had a mean BMI of 19.9 (SD = 4.7) and mean illness duration of 4.9 years (SD = 3.7). Attrition analyses comparing the final sample with all eligible patients on available data on eating disorder symptoms, BMI, age, self‐image (independent‐samples t‐test), and eating disorder diagnosis (chi‐square) showed no significant differences (all ts < .68 with ps > .50; χ2 = 4.54, p > .21, Φ = .08).

Instruments

Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB)

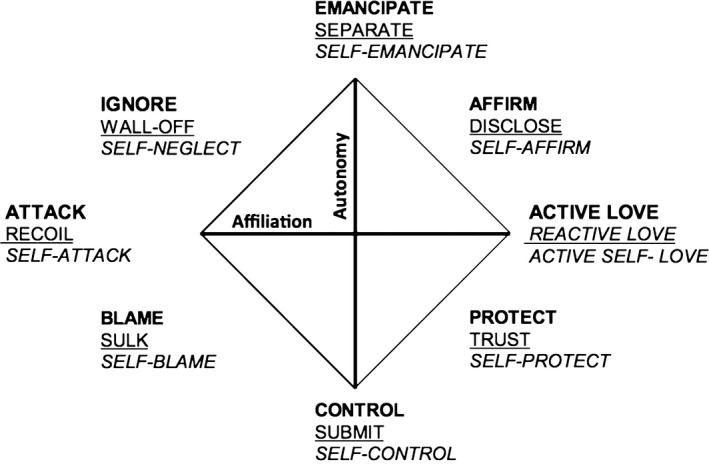

We operationalized the patient's relationship to her eating disorder using the Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB) model. It is based on interpersonal and attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969; Sullivan, 1953) and allows for examining dyadic interpersonal behaviours and self‐image (Benjamin, 1993, 2000). SASB is a circumplex model, that is, a model that consists of orthogonal dimensions of Affiliation (love–hate) and Autonomy (control–autonomy). There are three surfaces to the SASB model, each representing a specific focus of interpersonal behaviour: Surface 1 describes actions towards someone, Surface 2 describes reactions to someone, and Surface 3 describes actions towards oneself (self‐image). Figure 1 shows the cluster version of the SASB model, where eight clusters of behaviours are formed by combinations of the two dimensions on all three surfaces.

Figure 1.

The Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB) model. Bold: Surface 1 (focus on other); underlined: Surface 2 (focus on self); italics: Surface 3 (self‐image). From Benjamin (1996b). © The Guilford Press.

The SASB model has been used previously to examine relationships other than those between people: for example, relationships between psychiatric patients and their auditory hallucinations (Benjamin, 1989; Thomas, McLeod, & Brewin, 2009) and between substance abusers and their drug of choice (Sandor, 1996). The relationship patterns differed depending on diagnosis and substance used. For instance, in the latter study, opiate abusers rated their drugs higher on protection and lower on control and attack, compared to stimulant abusers.

The 72‐item Swedish translation of the SASB Intrex relationship form (Benjamin, 1996a) was used to rate how participants viewed their eating disorder as acting towards them (Surface 1, 36 items), and how they reacted in response (Surface 2, 36 items). The wording of items (rated 0–100) was modified to correspond to actions of the eating disorder (e.g., Surface 1: ‘It [the eating disorder] harshly punishes and tortures me, takes revenge’) and the reactions of the patient (e.g., Surface 2: ‘I give in to it [the eating disorder], yield and submit to it’). Before rating the Intrex, participants read a short text about seeing their eating disorder as a relational partner.

Structural Analysis of Social Behavior has good test–retest reliability for psychiatric patients rating different relationships, with Cronbach's alphas between .82 and .94 (Benjamin, 2000). The Swedish version has acceptable internal consistency, with alphas for the dimensional endpoints of Surfaces 1 and 2 above .65 (Armelius & Hakelind, 2007). In the present sample, alphas for the clusters varied from low to good. On Surface 1, Clusters 2, 3, 5, and 6 had acceptable alphas (ranging from .69 to .80). Clusters 1 and 7 attained acceptable alphas (>.71) when one item in each cluster (items 23 and 27) was removed and so these optimized versions of the clusters were used in the analyses. Clusters 4 and 8 had alphas below .65 and were excluded from the analyses when clusters were examined, although descriptive data on them are presented in Table 1. On Surface 2, Clusters 3, 4, 5, and 7 had acceptable alphas (ranging from .73 to .81). Cluster 2 attained acceptable alpha (.69) when one item (item 35) was removed, and consequently, this version of the cluster was used. Clusters 1, 6, and 8 had alphas below .65 and were excluded from analyses. Alphas for positive affiliation (Clusters 2, 3, and 4) and negative affiliation (Clusters 6, 7, and 8) were good for both surfaces (i.e., >.82).

Table 1.

Patients’ experiences of how the eating disorder acts (SASB Surface 1) and how the patient reacts to the eating disorder (SASB Surface 2)

| Eating disorder acting (Surface 1) | Emancipate | Affirm | Active love | Protect | Control | Blame | Attack | Ignore |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| AN (n = 55) | 27.4 (20.0) | 22.5 (22.1) | 29.9 (20.8) | 44.3 (18.7) | 72.0 (19.4) | 69.8 (23.9) | 47.7 (20.2) | 45.1 (23.3) |

| BN (n = 33) | 30.2 (17.9) | 25.9 (21.7) | 36.3 (23.7)* | 48.7 (18.5) | 72.1 (16.9) | 72.7 (16.9) | 53.7 (18.9) | 55.2 (21.6) |

| EDNOS (n = 62) | 23.6 (15.5) | 14.2 (15.5) | 22.4 (15.1)* | 43.7 (17.6) | 70.1 (19.7) | 75.7 (19.8) | 54.9 (18.3) | 50.1 (25.1) |

| Patient reacting (Surface 2) | Separate | Disclose | Reactive love | Trust | Submit | Sulk | Recoil | Wall‐off |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AN (n = 55) | 38.9 (18.7) | 37.0 (18.4) | 23.1 (19.6) | 41.3 (23.6) | 56.1 (22.6) | 52.4 (21.3) | 44.9 (21.7) | 42.0 (19.1) |

| BN (n = 33) | 39.4 (18.1) | 38.3 (20.8) | 30.6 (23.1) | 43.3 (23.6) | 61.8 (19.5) | 54.4 (22.3) | 49.3 (25.2) | 45.5 (17.3) |

| EDNOS (n = 62) | 37.2 (13.6) | 36.6 (19.1) | 21.1 (15.9) | 39.5 (21.7) | 59.1 (22.9) | 54.2 (20.1) | 49.7 (21.7) | 43.0 (19.2) |

SASB = Structural Analysis of Social Behavior; AN = anorexia nervosa; BN = bulimia nervosa; EDNOS = eating disorder not otherwise specified.

Patients also completed the 36‐item SASB self‐image (Surface 3) questionnaire. Both the original and the Swedish version have good internal consistency, with alphas above .76 (Armelius, 2001; Benjamin, 2000). The instrument discriminates well between clinical and normal samples (Benjamin, 2000; Björck, Clinton, Sohlberg, Hällström, & Norring, 2003), and between eating disorder diagnostic groups (Björck et al., 2003). Alphas for self‐image clusters in our sample were all above .70, with the exception of Cluster 1 (self‐emancipate), which was hence excluded from analyses. One patient had incomplete data on the SASB self‐image questionnaire and was excluded from the analysis involving self‐image.

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE‐Q)

This widely used 36‐item self‐report measure focuses on core eating disorder psychopathology (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994). It generates a total score and scores on four subscales: Eating Concern, Shape Concern, Weight Concern, and Restraint. The EDE‐Q has good psychometric properties and reference data (Luce & Crowther, 1999; Welch, Birgegård, Parling, & Ghaderi, 2011). In this sample, the mean on the total EDE‐Q score was 3.8 (SD = 1.3), comparable to the clinical sample in Welch et al. (2011). Alphas ranged between .68 (Eating Concern) and .94 (global score).

ED diagnosis

The Structured Eating Disorder Interview (SEDI) is a semi‐structured clinical interview used as the basis for assessing DSM‐IV eating disorder diagnosis and subtype in the Stepwise database. The interview consists of 20–30 questions, depending on which criteria the patient fulfils. It has good convergent validity; concordance with the Eating Disorder Examination Interview (Cooper & Fairburn, 1987), concerning the presence of eating disorder, it is 90.3% (sensitivity = .91, specificity = .80), and 81.0% concerning specific DSM‐IV eating disorder subdiagnosis (Kendall's Tau‐b .69, p < .001; De Man Lapidoth & Birgegård, 2010). Clinicians are presented with a preliminary suggested diagnosis and weigh in other clinical data along with the totality of the Stepwise assessment results to establish a final diagnosis.

Procedure

Patients were assessed using Stepwise by their third visit to the clinic. Assessment took about 45 min and comprised the SEDI as well as clinical ratings of functioning and eating disorder severity, demographics, and self‐report questionnaires (EDE‐Q, SASB self‐image, and other instruments not used here). Clinicians recorded weight and height, while duration of illness was self‐reported. Eligible participants were informed about the study. A research assistant then called the patients informing them further and asking whether they wished to participate. If patients agreed, they received the additional forms by post (i.e., SASB Relationship Intrex), along with a form for informed consent and a pre‐stamped return envelope. Once the completed forms were received, patients were rewarded with a gift certificate worth 100 SEK (approx. £8.60). The Regional Ethics Review approved the study (Registration no. 2013/968‐31/5).

Statistical analyses

Standardized scores for all eight clusters on both SASB relationship surfaces (1 and 2) that were beyond ±3 were considered outliers and removed before further analysis. This resulted in the removal of six scores on five clusters from four individuals. Two MANOVAs with post‐hoc Scheffé tests were performed to investigate potential differences at cluster level between diagnostic groups in how they experience: (1) their eating disorder as acting towards them (Surface 1); and (2) their own reactions to their eating disorder (Surface 2). These analyses were also rerun as MANCOVAs, controlling for duration of illness and eating disorder symptoms (EDE‐Q global score). Based on medium effect sizes, α = .01, and power = .95, the total N needed for MANCOVA was 81 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). To investigate whether eating disorder actions (Surface 1) and patient reactions (Surface 2) were associated with specific eating disorder symptoms and duration of illness, stepwise linear regression was conducted (10 analyses) in which eating disorder actions and patients’ reactions were used to predict EDE‐Q subscales and duration of illness, while controlling for initial eating disorder symptom status. A forward selection procedure was applied; based on the p‐value of F, the independent variable with the smallest p‐value was entered into the model, one at a time. This process was repeated until there was no further improvement in the model. Based on medium effect sizes, α = .01, and power = .95, the total N needed for regression analyses was 123 (Faul et al., 2007). These analyses were conducted on the sample as a whole. Prior to regression analyses, bivariate outliers were removed, defined as jackknife residuals beyond the critical t for p < .01. Jackknife residuals are studentized deleted residuals distributed as t with df = n‐k‐2, where k is the number of predictors (Kleinbaum, Kupper, & Muller, 1988). Finally, the degree of dissonance within the relationship (i.e., the relative strength between the eating disorder's actions and the patient's reactions) was examined in relation to eating disorder symptoms, duration of illness, and self‐image. Following SASB conventions, this was done by computing two new variables: weighted scores2 of Clusters 2, 3, and 4 (Affirm, Active Love, and Protect for Surface 1 and Disclose, Reactive Love, and Trust for Surface 2) were combined into positive affiliation and Clusters 6, 7, and 8 (Blame, Attack, and Ignore for Surface 1 and Sulk, Recoil, and Wall‐off for Surface 2) were combined into negative affiliation. Cluster 5 was used to measure low autonomy (Cluster 1 was excluded due to low alpha on Surface 2). Scores on Surface 2 (patients’ reactions) were subtracted from Surface 1 (the eating disorder's actions) for each of the three variables. Negative scores meant the patient scored her own behaviour higher in the relationship with the eating disorder (e.g., the patient was more submissive than the eating disorder was controlling), whereas positive scores meant that the eating disorder was rated more highly (e.g., the eating disorder attacked more than the patient recoiled). Each variable was then recoded into two dummy variables representing patients who reacted more or less in the relationship with the eating disorder. This meant that the dummy variables represented whether the patient was reacting with more negative affect, with more positive affect, or with more submission in relation to the three variables. Independent‐samples t‐tests were used to test for differences between the groups on EDE‐Q subscales, self‐image clusters, and illness duration. To reduce type I error in all analyses conducted, Bonferroni adjustment was applied, yielding a study‐wide α = .002 for significance.

Results

Diagnostic comparisons of eating disorder actions and patients’ reactions

Descriptive statistics for eating disorder actions (Surface 1) and patient reactions (Surface 2) are presented in Table 1. The highest values regarding eating disorder actions were observed for control (Cluster 5) and blame (Cluster 6) across all diagnoses, and patients reacted primarily by submitting (Cluster 5) to their eating disorder's control, and sulking (Cluster 6) in response to their eating disorder's blame3. Comparing diagnostic groups, there were no significant differences on any of the clusters of either surface.

Associations between aspects of the hypothetical patient–ED relationship and symptoms and illness duration

Table 2 presents results of stepwise regression analyses4. All EDE‐Q subscales were primarily explained by controlling actions (Cluster 5) of the eating disorder (i.e., between 12% and 18% of the variance in these variables). In terms of patients’ reactions, high patient submission (Cluster 5) explained the most variance in all EDE‐Q subscales (between 7% and 13% of the variance). Neither eating disorder actions nor patients’ reactions were significantly associated with duration of illness.

Table 2.

Stepwise regression results using eating disorder actions (SASB Surface 1) and patients’ reactions (SASB Surface 2) to predict EDE‐Q subscale scores and duration of illness

| Dependent variables | Step | Eating disorder acting (SASB surface 1): | Step | Patient reacting (SASB surface 2): | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indepedent variables | R 2 | β | t | p | Independent variables | R 2 | β | t | p | |||

| EDE‐Q Restraint | 1 | Controlling | 0.17 | .42 | 5.55 | <.001 | 1 | Submitting | 0.13 | .35 | 4.59 | <.001 |

| EDE‐Q Eating concern | 1 | Controlling | 0.18 | .42 | 5.7 | <.001 | 1 | Submitting | 0.12 | .35 | 4.56 | <.001 |

| EDE‐Q Shape concern | 1 | Controlling | 0.14 | .37 | 4.9 | <.001 | 1 | Submitting | 0.07 | .27 | 3.4 | .001 |

| EDE‐Q Weight concern | 1 | Controlling | 0.12 | .35 | 4.59 | <.001 | 1 | Submitting | 0.08 | .28 | 3.50 | .001 |

| Duration of illness | 1 | None | – | – | – | – | None | – | – | – | – | |

EDE‐Q = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; SASB = Structural Analysis of Social Behavior.

The dissonance between the eating disorder's actions and the patient's reactions

In terms of positive affiliation (e.g., loving, affirming, protecting), 59 of the patients reacted with more affiliation than their eating disorder invited them to, and 90 with less affiliation. There were no significant differences between positive affiliation groups on self‐image, eating disorder symptoms, or duration of illness. However, in terms of negative affiliation patients reacting more negatively (n = 38; e.g., recoil, protest, sulk) than their eating disorder acted (e.g., attack, ignore, blame) scored significantly higher on Self‐acceptance, Self‐love, and Self‐protection and lower on Restraint, Shape Concern, Weight Concern, and Total EDE‐Q, compared to patients who reacted with less negative affiliation towards their disorder (n = 111; see Table 3)5 . Patients reacting less negatively and patients reacting more negatively towards their disorder both rated their disorders as acting negatively towards them, with the group reacting less negatively rating their disorder's actions more negatively than the other group (M = −31.7, SD = 24.8, and M = −12.5, SD = 17.6, respectively, on the affiliation vector of Surface 1). Patients reacting more negatively tended to submit less to their eating disorder (M = 45.2, SD = 21.9) compared to those reacting less negatively (M = 63.2, SD = 20.2; t = −4.62, p < .001, effect size d = .70). There were no significant differences between these two groups on frequencies of key eating disorder behaviours measured by the EDE‐Q. Groups based on the control/submission dimension did not differ significantly on any of the variables.

Table 3.

Comparisons between those patients reacting with more negative affiliation on SASB Surface 2 towards their eating disorder and those with less negative affiliation, on SASB self‐image clusters (Surface 3), EDE‐Q subscales, and duration of illness (in years)

| Measure | More negative reaction to eating disorder (n = 38) | Less negative reaction to eating disorder (n = 111) | t | p | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||

| SASB Self‐affirmation | 41.4 (23.5) | 27.0 (17.9) | 3.47 | <.001 | .69 |

| SASB Self‐love | 40.7 (20.8) | 28.5 (17.8) | 3.49 | <.001 | .63 |

| SASB Self‐protection | 51.0 (20.5) | 38.0 (20.0) | 3.43 | <.001 | .64 |

| SASB Self‐control | 55.3 (15.2) | 58.4 (20.8) | .97 | ns | |

| SASB Self‐blame | 48.6 (30.5) | 59.9 (22.5) | 2.09 | ns | |

| SASB Self‐attack | 34.4 (27.0) | 47.5 (26.0) | 2.65 | ns | |

| SASB Self‐neglect | 34.8 (26.5) | 41.8 (23.1) | 1.53 | ns | |

| EDE‐Q Restraint | 2.9 (1.3) | 3.8 (1.5) | 3.41 | <.001 | .64 |

| EDE‐Q Eating Concern | 2.7 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.8) | 3.05 | ns | |

| EDE‐Q Shape Concern | 3.9 (1.6) | 4.9 (1.3) | 3.28 | <.001 | .69 |

| EDE‐Q Weight Concern | 3.2 (1.7) | 4.2 (1.5) | 3.30 | <.001 | .62 |

| EDE‐Q Total Score | 3.2 (1.3) | 4.1 (1.2) | 3.87 | <.001 | .72 |

| Illness duration | 4.3 (3.7) | 5.1 (3.7) | 1.17 | ns |

SASB = Structural Analysis of Social Behavior; EDE‐Q = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire.

Discussion

When asked to conceptualize their eating disorder as constituting a dyadic relationship, patients’ responses on the SASB showed clear patterns that resembled highly negative and enmeshed real‐life interpersonal relationships. In general, patients’ responses indicated that when asked to conceptualize their eating disorder as a relationship, they were likely to conceptualize one in which the eating disorder is blaming and controlling, and in which they sulk and submit in response. Eating disorder control and patient submission were associated with higher levels of symptomatology. Patients who reacted more negatively towards their disorders were less symptomatic. As the patients had not yet engaged in treatment, findings were unlikely to be due to therapist socialization.

The relational pattern reported by patients was similar irrespective of diagnosis, consistent with evidence that underlying psychological mechanisms may be similar across eating disorder diagnoses (e.g., Haynos & Fruzzetti, 2011; Tasca & Balfour, 2014). The actions of eating disorders tended to be experienced as controlling and blaming, while patients’ reactions were submitting and sulking. This is in line with the principle of interpersonal complementarity (Benjamin, Rothweiler, & Critchfield, 2006), which proposes that interpersonal behaviours evoke complementary responses in others and that relationships characterized by complementarity are stable. The relationship between patients and their disorders is characterized by patterns of interaction comparable to, for example, abusive relationships (Tierney & Fox, 2011). Unlike participants in the Tierney and Fox (2010) study, our patients did not feel much affiliation towards their illnesses, rather the opposite. They did however tend to submit to their eating disorders, highlighting a possible sense of immobilization in patients, which may pose a similar threat to recovery as feeling affiliation towards one's illness.

The insidious relationship

The patient–eating disorder relationship is insidious. Its harmful yet subtle effects are reflected in the central role of control and dominance that the disorder exerts in relation to the patient. High external locus of control, poor self‐regulation strategies, high perfectionism, and low assertiveness are all associated with more severe eating disorder psychopathology (Scoffier, Paquet, & d'Arripe‐Longueville, 2010; Slof‐Op't Landt, Claes, & Van Furth, 2016). Our results are further evidence of the central function of control in eating disorders, where submission to a controlling eating disorder was associated with greater symptomatology. This is also in line with research on the anorexic voice showing how a more powerful voice and a greater sense of being unable to get away from the voice are associated with lower BMI (Pugh & Waller, 2016a,b). This unhealthy rigid attachment, dominated by rules that patients feel obliged to adhere to, may be an inherent and maintaining component of the disorder.

Fighting the enemy within

Conceptualizing the voice of the illness in terms of a relationship implies a dyadic dynamic, which rather than removing responsibility from the patient may help empower patients to react differently in response to the demands of their eating disorders, thus potentially enhancing patients’ sense of self‐mastery and increasing their self‐compassion. Patients who reacted to their eating disorder by rebelling had more positive self‐images and less eating disorder symptoms than those who did not. Similarly, Duncan et al. (2015) found repossession of personal control and power, by defending against the false security offered by an eating disorder, to be central for recovery from anorexia nervosa. In SASB theory, relationship behaviours negative in affiliation (such as those that the rebellious patients in our study scored higher on) have the function specifically to correct imbalance in control/submission (Benjamin, 2003), consistent with our data. That is, those who were angry at their disorder also tended to submit to it less and were less symptomatic.

As interpersonal theory postulates that the way a person relates to important others is repeated in other relationships (Benjamin, 1993), a speculation is that patients reacting submissively to their eating disorders might repeat this pattern in relation to the therapist, passively complying but without commitment to change. Exploring the patient–eating disorder relationship in treatment may help therapists and patients from getting trapped in that pattern of relating and aid in forming a constructive alliance against the true enemy within. This could be done by mobilizing anger towards the illness, inducing cognitive dissonance, and encouraging patients to oppose their disorder and disobey it.

Limitations and future research

Our cross‐sectional data preclude causal or longitudinal conclusions regarding whether patients who rebel against their disorders have a better outcome. Although research suggests that positive self‐image predicts a better outcome (e.g., Björck, Clinton, Sohlberg, & Norring, 2007) and patients rebelling against their eating disorder had a more positive self‐image, longitudinal data are needed to elucidate the question. Our study focuses young females entering eating disorder treatment, which means we cannot generalize our findings to other groups, such as males and patients with severe, enduring, and treatment‐resistant eating disorders. Some SASB clusters did not have acceptable internal consistency, which could imply that patients found it difficult to assign such behaviours to the eating disorder. Moreover, we do not have data on the test–retest reliability for our modified version of the SASB. Further research is therefore needed to optimize and evaluate the utility of the SASB to help understand the relationship that patients have with their disorders. Further, we do not know why 46% of patients who were asked to participate never responded, and why 27% who agreed to participate failed to do so. Although some attrition is to be expected, it may have been related to the study's aims; some potential participants may have been unable to think of their eating disorder as an external entity or in terms of a relationship because for them this is simply inapplicable; that is, the disorder lacks this characteristic, while others may for other reasons have been unwilling to conceptualize their illness in this way, which then limits generalizability. Nevertheless, attrition analyses did not reveal any differences, tentatively supporting some generalizability of our findings. Finally, we do not know whether the patients in our study would spontaneously conceptualize their eating disorder as a relationship without being encouraged to do so. But the fact that our results show patterns of relating when patients were asked to consider their eating disorder in this way is in keeping with previous research where patients have spontaneously reported a relationship with their eating disorder. Moreover, the fact that patterns of relating emerged suggests that it might be helpful to introduce this concept in therapy to help people develop a vocabulary for making sense of their eating disorder and their own behaviours in response to it.

Conclusions

Our results support qualitative studies of eating disorders suggesting that some patients are able to conceptualize their eating disorder as constituting a dyadic relationship. The nature of this relationship is insidious; the eating disorder is experienced as offering a sense of control, when in fact the illness controls the patient, who in turn submits. A higher degree of eating disorder dominance and negative affiliation is associated with greater symptomatology and negative self‐image, which may act to maintain the disorder. Disobeying and rebelling against the eating disorder may be important for recovery. This could be aided by exploring the patient–eating disorder relationship in treatment and challenging ingrained patterns of how patients relate to their disorders.

Notes

Only females were selected as data on yearly intake of males at participating units suggested there would be too few matching inclusion criteria to constitute a group of sufficient size.

Weights were assigned according to Benjamin (2000) based on each cluster's proximity to the Affiliation dimension (Clusters 3 and 7 are multiplied by 7.8 and the diagonal clusters by 4.5), divided by 16.8 (the sum of the weights, which deviates from Benjamin (2000) but which we prefer as it brings the weighted score back to the original scale of 0 to 100).

The scores on these clusters are also high in comparison with normative data on conventional interpersonal relationships (Benjamin, 2000), ≈.5–1 SD higher in Control/Submit and ≈2.5–3 SD higher in Blame/Sulk.

These analyses were also conducted including all original SASB clusters regardless of alpha (for exploratory purposes). The overall pattern of results was similar to the results we present above.

Cross‐tabulating the affiliation variables and diagnoses and running chi‐square tests to examine differences within each affiliation variable showed no significant differences; that is, diagnosis did not seem to impact reaction group membership.

References

- Abbate‐Daga, G. , Amianto, F. , Delsedime, N. , De‐Bacco, C. , & Fassino, S. (2013). Resistance to treatment and change in anorexia nervosa: A clinical overview. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 294 10.1186/1471-244X-13-294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armelius, K. (2001). Reliabilitet och validitet för den svenska versionen av SASB självbildstestet [Reliability and validity for the Swedish version of SASB‐introject test]. Unpublished manuscript. Department of psychology, University of Umeå, Sweden.

- Armelius, K. , & Hakelind, C. (2007). Interpersonal complementarity‐ Self‐rated behavior by normal and antisocial adolescents with a liked and a disliked peer. Interpersona, 1(2), 99–116. 10.5964/ijpr.v1i2.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, L. S. (1989). Is chronicity a function of the relationship between the person and the auditory hallucination? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 15(2), 291–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, L. S. (1993). Interpersonal diagnosis and treatment of personality disorders. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, L. S. (1996a). A clinician‐friendly version of the interpersonal circumplex: Structural analysis of social behavior (SASB). Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(2), 248–266. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6602_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, L. S. (1996b). Interpersonal diagnosis and treatment of personality disorders (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, L. S. (2000). Intrex user's manual. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, L. S. (2003). Interpersonal reconstructive therapy. New York, NY: The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, L. S. , Rothweiler, J. C. , & Critchfield, K. L. (2006). The use of structural analysis of social behavior (SASB) as an assessment tool. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 83–109. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birgegård, A. , Björck, C. , & Clinton, D. (2010). Quality assurance of specialised treatment of eating disorders using large‐scale Internet‐based collection systems: Methods, results and lessons learned from designing the Stepwise database. European Eating Disorders Review, 18, 251–259. 10.1002/erv.1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björck, C. , Clinton, D. , Sohlberg, S. , Hällström, T. , & Norring, C. (2003). Interpersonal profiles in eating disorders: Ratings of SASB self‐image. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 76(4), 337–349. 10.1348/147608303770584719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björck, C. , Clinton, D. , Sohlberg, S. , & Norring, C. (2007). Negative self‐image and outcome in eating disorders: Results at 3‐year follow‐up. Eating Behaviors, 8(3), 398–406. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Z. , & Fairburn, C. G. (1987). The eating disorder examination: A semi‐structured interview for the assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198701)6:1<1:AID-EAT2260060102>3.0.CO;2-9 [Google Scholar]

- De Man Lapidoth, J. , & Birgegård, A. (2010). Validation of the structured eating disorder interview (SEDI) against the eating disorder examination (EDE). Stockholm, Sweden: Karolinska Institutet. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, T. K. , Sebar, B. , & Lee, J. (2015). Reclamation of power and self: A meta‐synthesis exploring the process of recovery from anorexia nervosa. Advances in Eating Disorders: Theory, Research and Practice, 3(2), 177–190. 10.1080/21662630.2014.978804 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C. G. , & Beglin, S. J. (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self‐report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16(4), 363–370. 10.1002/1098-108X (199412)16:4<363::AID-EAT2260160405>3.0.CO;2‐# [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C. G. , & Harrison, P. J. (2003). Eating disorders. Lancet, 361, 407–416. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12378-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassino, S. , Piero, A. , Tomba, E. , & Abbate‐Daga, G. (2009). Factors associated with dropout from treatment for eating disorders: A comprehensive literature review. BMC Psychiatry, 9, 67. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F. , Erdfelder, E. , Lang, A. G. , & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioural, and biomedical sciences. Behaviour Research Methods, 39, 175–191. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsén Mantilla, E. , & Birgegård, A. (2015). The enemy within: The association between self‐image and eating disorder symptoms in healthy, non help‐seeking and clinical young women. Journal of Eating Disorders, 3, 30 https://doi.org/10.1186%2Fs40337-015-0067-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halmi, K. A. (2013). Perplexities of treatment resistance in eating disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 292 10.1186/1471-244X-13-292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynos, A. F. , & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2011). Anorexia nervosa as a disorder of emotion dysregulation: Evidence and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology‐Science and Practice, 18, 183–202. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01250.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum, D. G. , Kupper, L. L. , & Muller, K. E. (1988). Applied regression analysis and other multivariate methods (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: PWS‐KENT Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Luce, K. H. , & Crowther, J. H. (1999). The reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination‐Self‐Report Questionnaire version (EDE‐Q). International Journal of Eating Disorders, 25(3), 349–351. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X (199904)25:3.0.CO;2‐M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordenbos, G. , Aliakbari, N. , & Campbell, R. (2014). The relationship among critical inner voices, low self‐esteem, and self‐criticism in eating disorders. Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment and Prevention, 22, 337–351. 10.1080/10640266.2014.898983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norring, C. , & Sohlberg, S. (1993). Outcome, recovery, relapse, and mortality across six years in patients with clinical eating disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia, 87, 437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03401.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, M. (2016). The internal ‘anorexic voice’: A feature or fallacy of eating disorders? Advances in Eating Disorders: Theory, Research and Practice, 4(1), 75–83. 10.1080/21662630.2015.1116017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, M. , & Waller, G. (2016a). The anorexic voice and severity of eating pathology in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49, 622–625. 10.1002/eat.22499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, M. , & Waller, G. (2016b). Understanding the ‘anorexic voice’ in anorexia nervosa. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 24, 670–676. 10.1002/cpp.2034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- af Sandeberg, A. , Birgegård, B. , Mohlin, L. , Nordlander Ström, C. , Norring, C. , & Siverstrand, M.‐L. (2009). Regionalt vårdprogram, ätstörningar. [Regional care programme, eating disorders] Medicinskt programarbete, Stockholms Läns Landsting. [in Swedish]

- Sandor, C. (1996). An interpersonal approach to substance abuse. PhD Thesis. University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

- Scoffier, S. , Paquet, Y. , & d'Arripe‐Longueville, F. (2010). Effect of locus of control on disordered eating in athletes: The mediational role of self‐regulation of eating attitudes. Eating Behaviors, 11, 164–169. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, N. , Hanstock, T. L. , & Patterson‐Kane, L. (2013). Using narrative therapy to treat Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified. Clinical Case Studies, 12(4), 307–321. 10.1177/1534650113486184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, L. , & Treasure, J. (2002). Bulimia nervosa: Friend or foe? The pros and cons of bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 32, 164–170. 10.1002/eat.10076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, L. , Treasure, J. , Teasdale, J. , & Sullivan, V. (1999). Anorexia nervosa: Friend or foe? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 25, 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199903)25:2<177:AID-EAT7>3.0.CO;2-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slof‐Op't Landt, M. C. , Claes, L. , & Van Furth, E. F. (2016). Classifying eating disorders based on “healthy” and “unhealthy” perfectionism and impulsivity. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(7), 673–680. 10.1002/eat.22557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York, NY: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Tasca, G. A. , & Balfour, L. (2014). Attachment and eating disorders: A review of current research. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(7), 710–717. 10.1002/eat.22302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, N. , McLeod, H. J. , & Brewin, C. R. (2009). Interpersonal complementarity in responses to auditory hallucinations in psychosis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 48(4), 411–424. 10.1348/014466509X411937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney, S. , & Fox, J. R. (2010). Living with the anorexic voice: A thematic analysis. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 83, 243–254. 10.1348/147608309X480172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney, S. , & Fox, J. R. (2011). Trapped in a toxic relationship: Comparing the views of women living with anorexia nervosa to those experiencing domestic violence. Journal of Gender Studies, 1, 31–41. 10.1080/09589236.2011.542018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welch, E. , Birgegård, A. , Parling, T. , & Ghaderi, A. (2011). Eating disorder examination questionnaire and clinical impairment assessment questionnaire: General population and clinical norms for young adult women in Sweden. Behavior Research and Therapy, 49, 85–91. 10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S. , & Reid, M. (2012). ‘It's like there are two people in my head’: A phenomenological exploration of anorexia nervosa and its relationship to the self. Psychology & Health, 27(7), 798–815. 10.1080/08870446.2011.595488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]