Summary

Objective

Since 2014, cannabidiol (CBD) has been administered to patients with treatment‐resistant epilepsies (TREs) in an ongoing expanded‐access program (EAP). We report interim results on the safety and efficacy of CBD in EAP patients treated through December 2016.

Methods

Twenty‐five US‐based EAP sites enrolling patients with TRE taking stable doses of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) at baseline were included. During the 4‐week baseline period, parents/caregivers kept diaries of all countable seizure types. Patients received oral CBD starting at 2‐10 mg/kg/d, titrated to a maximum dose of 25‐50 mg/kg/d. Patient visits were every 2‐4 weeks through 16 weeks and every 2‐12 weeks thereafter. Efficacy endpoints included the percentage change from baseline in median monthly convulsive and total seizure frequency, and percentage of patients with ≥50%, ≥75%, and 100% reductions in seizures vs baseline. Data were analyzed descriptively for the efficacy analysis set and using the last‐observation‐carried‐forward method to account for missing data. Adverse events (AEs) were documented at each visit.

Results

Of 607 patients in the safety dataset, 146 (24%) withdrew; the most common reasons were lack of efficacy (89 [15%]) and AEs (32 [5%]). Mean age was 13 years (range, 0.4‐62). Median number of concomitant AEDs was 3 (range, 0‐10). Median CBD dose was 25 mg/kg/d; median treatment duration was 48 weeks. Add‐on CBD reduced median monthly convulsive seizures by 51% and total seizures by 48% at 12 weeks; reductions were similar through 96 weeks. Proportion of patients with ≥50%, ≥75%, and 100% reductions in convulsive seizures were 52%, 31%, and 11%, respectively, at 12 weeks, with similar rates through 96 weeks. CBD was generally well tolerated; most common AEs were diarrhea (29%) and somnolence (22%).

Significance

Results from this ongoing EAP support previous observational and clinical trial data showing that add‐on CBD may be an efficacious long‐term treatment option for TRE.

Keywords: cannabidiol, efficacy, expanded access program, seizures, tolerability, treatment‐resistant epilepsy

Key Points.

Of the 607 patients treated (median treatment duration 48 weeks; range 2‐146 weeks), 76% of patients remained on treatment

Cannabidiol (CBD) was associated with 51% and 48% reductions in median monthly convulsive and total seizures, respectively, after 12 weeks of treatment

Reductions in median monthly convulsive and total seizures were similar among visit windows through 96 weeks of treatment

At visits between weeks 12 and 96, inclusive, the ≥50%, ≥75%, and 100% response rates were notable and similar among time points

Overall, CBD was generally well tolerated; treatment‐emergent adverse events (AEs) were consistent with those reported previously

1. INTRODUCTION

Antiseizure drugs, referred to commonly as antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), provide only partial relief of seizures in treatment‐resistant epilepsies (TRE), frequently at the cost of severe adverse effects (AEs). Newer AEDs seek to improve efficacy and/or reduce these AEs. To date, a pharmaceutical formulation of highly purified cannabidiol (CBD) has demonstrated an acceptable safety profile,1, 2, 3, 4 but additional long‐term safety and efficacy data are needed.

The therapeutic potential of CBD as an AED has been of great interest, particularly for TREs. Preclinical studies in animal models5, 6 and open‐label studies2, 7, 8 suggest that CBD has antiseizure properties in a broad range of epilepsies. Recent findings from 3, phase 3 clinical trials showed that add‐on CBD was efficacious for seizures associated with Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome (LGS)3, 4 and Dravet syndrome (DS).1

In January 2014, an expanded access program (EAP) was initiated to provide CBD to patients with TRE. During the first year of the study, the primary objective was to establish the safety and tolerability of CBD, and the secondary objective was to obtain preliminary efficacy data, which have been reported previously.2 Herein we provide an update, reporting pooled results for safety outcomes up to 144 weeks and efficacy endpoints up to 96 weeks in more than 600 patients treated through December 2016.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and patient population

This open‐label EAP included 29 individual physician‐ or state‐initiated Investigational New Drug (IND) applications, conducted at 25 US‐based epilepsy centers. Patient eligibility criteria and endpoints varied by site‐specific protocols, but all patients had TRE and were receiving stable doses of AEDs for ≥4 weeks before enrollment. An institutional review board at each site approved the study protocols, and patients or parents/caregivers provided written informed consent before any study‐related assessments were performed. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local standard operating procedures.

2.2. Procedures

During the 4‐week baseline period, parents/caregivers kept diaries of all countable seizure types.

Data were collected on convulsive and total seizures. Convulsive seizures were defined as tonic, clonic, tonic–clonic, atonic, or secondary generalized. Not all patients reported convulsive seizures. Nonconvulsive seizures were defined as myoclonic, absence, or myoclonic‐absence seizures, and focal seizures with or without impaired consciousness. Concomitant AEDs were recorded at baseline; dose modifications were allowed and recorded during follow‐up. After the baseline observation period, patients received a plant‐derived, pharmaceutical formulation of purified CBD (100 mg/mL) in oral solution (Epidiolex; GW Research Ltd) at a gradually increasing dose starting at 2‐10 mg/kg/d until tolerability limit or a maximum dose of 25‐50 mg/kg/d, depending on the site.

Patients were seen every 2‐4 weeks through week 16 and every 2‐12 weeks thereafter. For each visit, there was a prespecified target day and visit window. If more than 1 visit occurred within a particular window, the data from the visit closest to the target day were used. If there were 2 visits within equal distance from the target day, the data were averaged for these visits. Some sites collected data at 2 and 4 weeks; therefore, it was assumed that the 4‐weeks of data were reported as weeks 2‐4, for the most conservative estimate.

2.3. Assessment of efficacy

Seizure frequency per week since the previous visit was provided by each site. For this report, all efficacy outcomes were assessed for the 12‐, 24‐, 48‐, 72‐, and 96‐week visit windows based on data available since the prior visit. For convulsive and total seizures, weekly seizure frequency was converted to frequency per 28 days (weekly frequency × 4). Percentage change in seizure frequency for each patient was calculated as ([seizure frequency per 28 days] − [seizure frequency at baseline]) / [seizure frequency at baseline] × 100. Due to the wide interpatient variability, median percentage changes in seizure frequency were calculated. Response rates were calculated as the proportions of patients who had at least 50%, 75%, and 100% reduction in monthly convulsive and total seizure frequency compared to baseline.

2.4. Assessment of dose

The use of concomitant AEDs was evaluated for 8 of the most commonly used agents (clobazam, lamotrigine, topiramate, rufinamide, valproic acid, levetiracetam, stiripentol, and felbamate). Total daily dose, summarized on a continuous scale, was recorded at baseline and during the treatment period. For each AED, results are presented for the number of patients with a stable dose at each visit, the number of patients with reduced dose at any time, and the number of patients with increased dose at any time.

2.5. Assessment of safety

Treatment‐emergent AEs (TEAEs) were monitored and classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, V17.1). Clinical laboratory parameters and vital signs were evaluated at regular time points during the study. Incidences of AEs, serious AEs, AEs leading to discontinuation, and AEs occurring in >10% of patients were assessed. In addition, the incidence of somnolence/sedation was assessed by concomitant clobazam use.

2.6. Analysis

Sample size was not predetermined but based on patient enrollment at the study sites. The safety analysis set was composed of all patients who had ≥1 dose of CBD and ≥1 postbaseline evaluation. All patients in the safety analysis set who had >0 seizures at baseline and seizure data for ≥1 postbaseline visit were included in the efficacy analysis set. A last‐observation‐carried‐forward (LOCF) analysis was performed using the data from the last available visit window for all patients with postbaseline efficacy data for convulsive seizures (462/580) and total seizures (575/580).

3. RESULTS

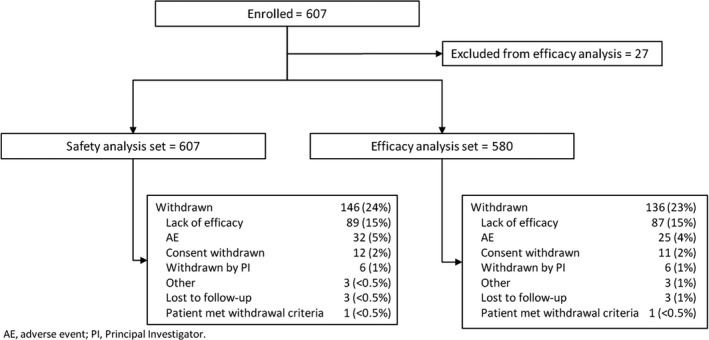

Between January 15, 2014 and December 16, 2016, 607 patients were enrolled in the EAP at US‐based sites; the median number of patients per site was 18 (range 1‐61). The safety analysis included 607 patients; the efficacy analysis included 580 patients. Of 607 patients in the safety dataset, 146 (24%) withdrew, mostly due to lack of efficacy (89 [15%]) or AEs (32 [5%]; Figure 1). Withdrawals were spread evenly across the treatment windows (Table S1). Because the EAP is ongoing, this analysis includes patients with a range of treatment duration (2‐146 weeks); median (25th percentile [Q1], 75th percentile [Q3]) treatment duration was 48 (23, 95) weeks, with efficacy data available through 96 weeks for 138 patients. Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients included in the safety and efficacy analyses. In both groups, mean age was 13 years (range 0.4‐62 years), and 52% of patients were male. A broad range of etiologies were included. The median number of concomitant AEDs taken at baseline was 3 (range 0‐10), and the most common medications were clobazam (51%), levetiracetam (34%), and valproic acid (29%; including semi‐sodium valproate, sodium valproate). A full listing of concomitant AEDs taken by ≥3% of patients is provided in Table S2.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition

Table 1.

Patient disposition and baseline demographics

| Efficacy analysis set (n = 580) | Safety analysis set (n = 607) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (range), y | 13.1 (0.4‐62.1) | 13.2 (0.4‐62.1) |

| Epilepsy diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome | 92 (16) | 94 (15) |

| Dravet syndrome | 55 (9) | 58 (10) |

| Tuberous sclerosis complex | 26 (4) | 26 (4) |

| Aicardi syndrome | 17 (3) | 19 (3) |

| CDKL5 | 18 (3) | 19 (3) |

| Doose, Dup15q, or febrile infection‐related epilepsy syndromes | 22 (4) | 24 (4) |

| Othera | 236 (41) | 243 (40) |

| Unknowna | 114 (20) | 124 (20) |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 302 (52) | 313 (52) |

| Concomitant AEDs taken at baseline, median (rangeb) | 3 (0‐10) | 3 (0‐10) |

| Convulsive seizures/28 d, median (Q1, Q3) | 43 (12, 112) | – |

| Total seizures/28 d, median (Q1, Q3) | 72 (22, 196) | – |

AEDs, antiepileptic drugs.

Diagnoses recorded for patients in the “other” and “unknown” categories were mostly refractory epilepsy, idiopathic generalized epilepsy, seizures, and intractable epilepsy; specific etiologies recorded for several patients each included genetic abnormalities, focal epilepsy, Sturge‐Weber syndrome, lissencephaly, cortical malformation/dysplasia, and myoclonic absence.

There were 3 patients in the safety analysis set and 2 in the efficacy analysis set who were not taking any concomitant AEDs at baseline.

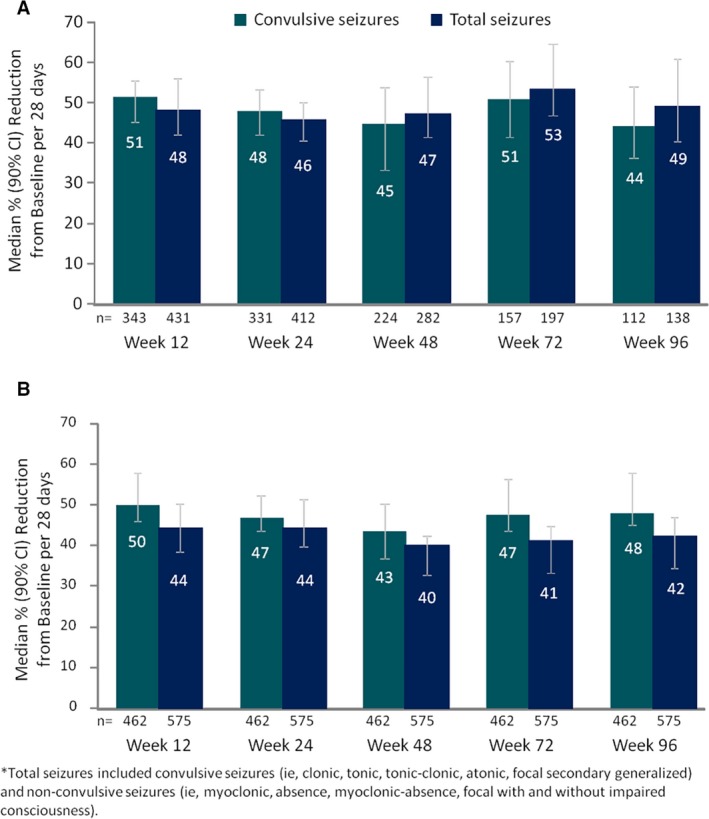

At baseline, the median (Q1, Q3) monthly frequency of convulsive and total seizures was 43 (12, 112) and 72 (22, 196), respectively (Table 1). After 12 weeks of treatment, the median monthly frequency of convulsive seizures was reduced by 51% and the frequency of total seizures was reduced by 48% (Figure 2A). For both convulsive and total seizures, median percentage reductions in monthly frequency were similar at each visit window through 96 weeks. Results from the LOCF analysis of median percentage seizure reduction showed that the observed reductions in seizure frequency were not affected by dropouts (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Percentage reduction from baseline in convulsive and total* seizures for (A) efficacy analysis set and (B) LOCF analysis. *Total seizures included convulsive seizures (ie, clonic, tonic, tonic–clonic, atonic, focal secondary generalized) and nonconvulsive seizures (ie, myoclonic, absence, myoclonic‐absence, focal with and without impaired consciousness). LOCF, last‐observation‐carried‐forward

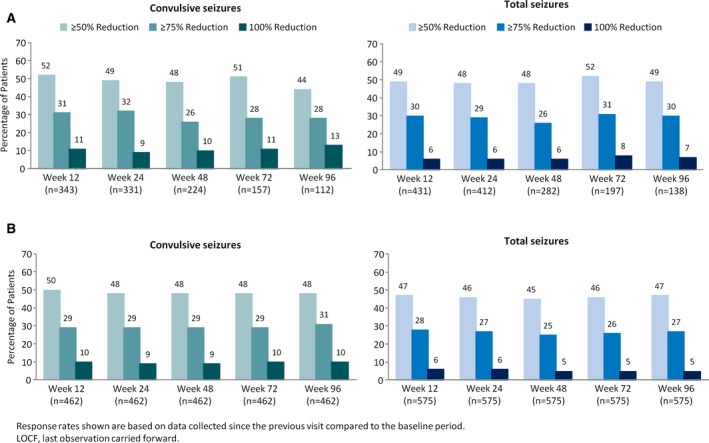

For convulsive seizures, the percentage of patients with ≥50%, ≥75%, and 100% reductions compared to baseline were 52%, 31%, and 11%, respectively, at week 12. For total seizures, the percentage of patients with ≥50%, ≥75%, and 100% reductions were 49%, 30%, and 6%, respectively, at week 12 (Figure 3A). Response rates for convulsive and total seizures were similar during the 12‐ through 96‐week visit windows even when accounting for withdrawals in the LOCF analysis (Figure 3B). The percentage of patients with an increase in seizure frequency (ie, >0% change from baseline) was similar for the 12‐, 24‐, 48‐, 72‐, and 96‐week visit windows, ranging from 20%‐27% for convulsive seizures and 19%‐25% for total seizures. Corresponding ranges for the LOCF analysis were 23%‐29% and 24%‐27%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Treatment response rates for the (A) efficacy analysis set and (B) LOCF analysis. LOCF, last‐observation‐carried‐forward

The median dose of CBD between weeks 12 and 96 (inclusive) was 25 mg/kg/d. Fifty‐five percent (330/605) of patients reduced their dose of CBD at any time during follow‐up. At baseline, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) doses were 32 (19) mg/d for clobazam and 891 (528) mg/d for valproate. Approximately half of the patients taking concomitant clobazam (181/305) and valproate (88/176) reduced their dose from baseline during the study. Among those taking concomitant levetiracetam, most remained on their baseline dose (mean [SD], 1986 [1552] mg/d; Table 2).

Table 2.

AED dosing information

| AED dose adjustments,a n (%) | Clobazam (n = 305) | Valproate (n = 176) | Levetiracetam (n = 208) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline dose stable at all visits | 84 (28) | 66 (38) | 132 (63) |

| Baseline dose increased | 25 (8) | 11 (6) | 23 (11) |

| Baseline dose decreased | 181 (59) | 88 (50) | 43 (21) |

| Baseline dose increased and decreased | 15 (5) | 11 (6) | 10 (5) |

AED, antiepileptic drug.

After initiating CBD treatment.

In the safety analysis group, with a median treatment duration of 48 weeks (range 2‐146 weeks), 88% of all patients experienced treatment‐emergent AEs and 33% experienced serious AEs (Table 3). The most commonly reported all‐cause AEs were diarrhea (29%), somnolence (22%), and convulsion (17%). The most common all‐cause serious AEs were convulsion (9%), status epilepticus (7%), pneumonia (5%), and vomiting (3%). Abnormal liver AEs (ie, alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase >3 × upper limit of normal) were reported for 10% (61/607) of patients; of these, 46 (75%) were on valproate. Ten percent (61/607) of patients had ≥1 of the MedDRA Preferred Terms for pneumonia; no patients discontinued treatment due to pneumonia. Of patients taking concomitant clobazam, 38% (123/320) experienced somnolence compared to 14% (40/287) not taking concomitant clobazam; overall 1 patient discontinued the treatment due to somnolence. There were 12 deaths during the study; none were considered related to treatment by investigators. Two deaths were due to sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP).

Table 3.

Summary of adverse events

| CBD dose (mg/kg/d) | All (N = 607) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0‐10 (n = 42) | >10‐20 (n = 115) | >20‐30 (n = 317) | >30‐40 (n = 59) | >40 (n = 74) | ||

| Overall AE rate | 27 (64.3) | 98 (85.2) | 286 (90.2) | 56 (94.9) | 69 (93.2) | 536 (88.3) |

| Overall serious AE rate | 4 (9.5) | 31 (27.0) | 112 (35.3) | 19 (32.2) | 33 (44.6) | 199 (32.8) |

| AEs leading to discontinuation | 5 (11.9) | 6 (5.2) | 17 (5.4) | 2 (3.4) | 1 (1.4) | 31 (5.1) |

| AEs reported in >10% of patients in any group by MedDRA preferred term, n (%) | ||||||

| Diarrhea | 6 (14.3) | 28 (24.3) | 92 (29.0) | 24 (40.7) | 27 (36.5) | 177 (29.2) |

| Somnolence | 5 (11.9) | 17 (14.8) | 76 (24.0) | 11 (18.6) | 27 (36.5) | 136 (22.4) |

| Convulsion | 3 (7.1) | 12 (10.4) | 62 (19.6) | 8 (13.6) | 17 (23.0) | 102 (16.8) |

| URTI | 5 (11.9) | 11 (9.6) | 41 (12.9) | 9 (15.3) | 9 (12.2) | 75 (12.4) |

| Decreased appetite | 2 (4.8) | 7 (6.1) | 45 (14.2) | 12 (20.3) | 9 (12.2) | 75 (12.4) |

| Vomiting | 0 | 10 (8.7) | 44 (13.9) | 3 (5.1) | 12 (16.2) | 69 (11.4) |

| Fatigue | 2 (4.8) | 11 (9.6) | 35 (11.0) | 9 (15.3) | 8 (10.8) | 65 (10.7) |

| Pyrexia | 1 (2.4) | 9 (7.8) | 40 (12.6) | 5 (8.5) | 8 (10.8) | 63 (10.4) |

| Status epilepticus | 1 (2.4) | 8 (7.0) | 21 (6.6) | 4 (6.8) | 11 (14.9) | 45 (7.4) |

| Pneumonia | 2 (4.8) | 3 (2.6) | 23 (7.3) | 3 (5.1) | 10 (13.5) | 41 (6.8) |

AE, adverse event; CBD, cannabidiol; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

4. DISCUSSION

This second interim analysis of the pooled EAP data, in which 138 patients had efficacy data available through 96 weeks, demonstrates that add‐on CBD can provide clinically meaningful and sustained reductions in the frequency of convulsive and total seizures across multiple epilepsy etiologies. The high proportions of patients achieving ≥50% and ≥75% reductions in seizure frequency were consistent at each visit window. Even in this highly treatment‐resistant population, during each visit window, some patients reported 100% seizure reduction from baseline for the period since their prior visit.

Cannabidiol was generally well tolerated. AE rates were similar to those reported in the initial analysis of the EAP, as well as to those reported in randomized controlled trials, with the most common AEs being somnolence and diarrhea. The most common serious AEs were convulsion (9%), status epilepticus (7%), pneumonia (5%), and vomiting (3%), which is consistent with previous reports on patients with severe TREs.1, 2, 3, 4 The overall incidence of AEs was markedly lower in the <10 mg/kg/d group than the other dose groups. In addition, the incidences of somnolence and diarrhea tended to increase with increasing dose, suggesting a dose effect.

During the follow‐up period, which extended through 2 years for some patients (median treatment duration of 48 weeks), 76% of patients remained on treatment. This retention rate compares favorably to other AED trials in TREs (63%‐72%).9, 10 This is possibly due to maintenance of long‐term efficacy and/or adverse events that were generally mild; improvements in quality of life11, 12 and seizure severity13 also have been reported with CBD, likely resulting in better retention. Withdrawals were spread relatively consistently through the study follow‐up period, and the LOCF sensitivity analysis demonstrated consistent reductions in seizure frequency when data from withdrawn patients were carried through the 96‐week visit window. Although CBD dose fluctuated during the study with over half of the patients reducing their dose at some point, the median dose remained stable (25 mg/kg/d) at all time points assessed. Unfortunately, the reasons for CBD dose decreases were not consistently recorded.

Cannabidiol has a bidirectional drug–drug interaction with clobazam. It inhibits cytochrome P450 (CYP)2C19 and increases levels of the nordesmethyl metabolite of clobazam, which has biologic activity.14 In addition, clobazam has been shown to increase levels of CBD's metabolite, 7‐hydroxy‐CBD.15 Our patients on concomitant clobazam reported over twice the incidence of somnolence than those not taking clobazam. However, only 1 patient discontinued treatment due to somnolence.

Seventy‐five percent of the patients with liver‐related AEs were taking concomitant valproic acid. Several patients who experienced elevation of liver function tests during the EAP were re‐titrated to the baseline CBD dose after valproic acid was discontinued and did not experience any further liver enzyme abnormalities,14 although it should be noted the data related to re‐titration were not consistently collected. A dose‐ranging safety study of CBD in the treatment of the DS showed that CBD had no effect on systemic levels of valproate, which suggests that the interaction between CBD and valproic acid may be pharmacodynamic rather than pharmacokinetic.16

Most patients taking concomitant clobazam and valproate reduced their doses during the follow‐up, potentially reflecting either the higher incidence of certain AEs observed when these AEDs are administered concomitantly with CBD or the desire of patients to wean from poly‐drug therapy when seizures become better controlled. In addition, a possible interaction between CBD and warfarin necessitating International Normalized Ratio (INR) monitoring in 1 patient from this EAP has been described previously.17

The study has several limitations. The EAP is not placebo‐controlled and the investigators and the patients are not blinded. Moreover, there was intersite variability in reporting methods, and information such as the reasons for AED dose reductions was not captured. Although parents/caregivers reported only the specific seizures that were countable, some seizure types that can be difficult to count (eg, absence) were included in the total seizure frequency data. In some of the site protocols, enrollment was dependent on predetermined seizure frequency, which was known to possible participants; hence, baseline overreporting cannot be completely excluded in this prospective data collection. Nevertheless, the pooled data across the EAP provides initial insights on the long‐term treatment effect of CBD that support the recent evidence from rigorous, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials showing meaningful reductions in seizure frequency for patients who received add‐on CBD vs placebo.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

In the last 2 years, Dr. Szaflarski received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Science Foundation (NSF), Shor Foundation for Epilepsy Research, EFA, the US Department of Defense, UCB Biosciences, NeuroPace Inc., SAGE Therapeutics Inc., Greenwich Biosciences Inc., Serina Therapeutics Inc., and Eisai, Inc.; served as a consultant for SAGE Therapeutics Inc., Greenwich Biosciences Inc., NeuroPace, Inc., Upsher‐Smith Laboratories, Inc., Medical Association of the state of Alabama, Serina Therapeutics Inc., LivaNova Inc., Lundbeck, and Elite Medical Experts LLC.; serves as an editorial board member for Epilepsy & Behavior, Journal of Epileptology (associate editor), Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience (associate editor), Journal of Medical Science, Epilepsy Currents (contributing editor), and Folia Medica Copernicana. E. Martina Bebin has received support from GW Pharmaceuticals as a principal investigator, and she has served on an advisory panel for GW Pharmaceuticals. Anup D. Patel has received research funding from Upsher‐Smith, LivaNova, Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation, and Greenwich Biosciences. He has performed consulting work for LivaNova, Greenwich Biosciences, Supernus, and Medscape. Linda Laux has received research funding from Zogenix and Greenwich Biosciences and has served on an advisory panel for Zogenix. Dr. Lyons has received support from GW Pharmaceuticals; has served as a paid consultant for Greenwich Biosciences Inc, UCB Biosciences, and Lundbeck; serves on the Epilepsy Foundation of Virginia Medical Board; and has advised the Commonwealth of Virginia Board of Pharmacy. Daniel Checketts is an employee of GW Research Ltd; Lisa De Boer is an employee of Greenwich Biosciences and owns stock in GW Pharmaceuticals. Matthew Wong has received research support from GW Pharmaceuticals. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The expanded‐access program was supported by grants from GW Research Ltd and the Epilepsy Therapy Project of the Epilepsy Foundation. State of Alabama General Funds supported the Alabama EAP (Carly's Law). Funding for the EAP in New York was provided by the New York State Department of Health. GW Research Ltd provided CBD free of charge, administrative support across all sites, and provided some sites with funds to support the study. At some sites, funds were provided for salary support for staff time spent on activities required for the EAP. GW Research Ltd collected the data from the sites and conducted the statistical analyses. The authors would like to thank the patients, their families, and the sites that provided data for this analysis.

APPENDIX 1. CBD EAP STUDY GROUP

1.1.

Jules C. Beal (Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College in Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA); Martina E. Bebin (University of Alabama Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA); Michael Chez (Sutter Health, Roseville, CA, USA); Anne M. Comi (Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, MD, USA); Orrin Devinsky (NYU Langone's Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, New York, NY, USA); Robert Flamini (PANDA Neurology, Atlanta, GA, USA); Charuta Joshi (University of Iowa Children's Hospital, Iowa City, IA, USA); Linda C. Laux (Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA); Merrick Lopez (Loma Linda University Children's Hospital, Loma Linda, CA, USA); Paul D. Lyons (Winchester Neurological Consultants, Winchester, VA, USA); Eric D. Marsh (Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA); Ian Miller (Miami Children's Hospital, Miami, FL, USA); Yong Park (Augusta University Medical Center, Augusta, GA, USA); Anup D. Patel (Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA); Eric Segal (Northeast Regional Epilepsy Group, Hackensack, NJ, USA); Laurie Seltzer (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, MN, USA); Jerzy P. Szaflarski (University of Alabama Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA); Elizabeth A. Thiele (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA); Robert Wechsler (Idaho Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, Boise, ID, USA); Arie Weinstock (Women and Children's Hospital of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA); Matthew H. Wong (Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston‐Salem, NC, USA); Pilar Pichon Zentil (Loma Linda University Children's Hospital, Loma Linda, CA, USA).

Szaflarski JP, Bebin EM, Comi AM, et al. Long‐term safety and treatment effects of cannabidiol in children and adults with treatment‐resistant epilepsies: Expanded access program results. Epilepsia. 2018;59:1540–1548. 10.1111/epi.14477

CBD EAP Study Group authors are presented in Appendix.

Contributor Information

Jerzy P. Szaflarski, Email: jszaflarski@uabmc.edu.

CBD EAP study group:

Michael Chez, Robert Flamini, Eric D. Marsh, Ian Miller, Yong Park, Eric Segal, Laurie Seltzer, Elizabeth A. Thiele, and Arie Weinstock

REFERENCES

- 1. Devinsky O, Cross JH, Laux L, et al. Trial of cannabidiol for drug‐resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2011–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Devinsky O, Marsh E, Friedman D, et al. Cannabidiol in patients with treatment‐resistant epilepsy: an open‐label interventional trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:270–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patel A, Devinsky O, Cross JH, et al. Cannabidiol (CBD) significantly reduces drop seizure frequency in Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome (LGS): results of a dose‐ranging, multi‐center, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial (GWPCARE3). Neurology. 2017;89:e100. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thiele EA, Marsh ED, French JA, et al. Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1085–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones NA, Glyn SE, Akiyama S, et al. Cannabidiol exerts anti‐convulsant effects in animal models of temporal lobe and partial seizures. Seizure. 2012;21:344–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones NA, Hill AJ, Smith I, et al. Cannabidiol displays antiepileptiform and antiseizure properties in vitro and in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:569–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gofshteyn JS, Wilfong A, Devinsky O, et al. Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for febrile infection‐related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES) in the acute and chronic phases. J Child Neurol. 2017;32:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hess EJ, Moody KA, Geffrey AL, et al. Cannabidiol as a new treatment for drug‐resistant epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsia. 2016;57:1617–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Toledo M, Beale R, Evans JS, et al. Long‐term retention rates for antiepileptic drugs: a review of long‐term extension studies and comparison with brivaracetam. Epilepsy Res. 2017;138:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Janssen Korea Ltd . An observational study to evaluate long‐term retention rate of topiramate in participants with epilepsy, 2013. Available from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01682681.

- 11. Gaston T, Szaflarski M, Hansen B, et al. Improvement in quality of life ratings after one year of treatment with pharmaceutical formulation of cannabidiol (CBD). Epilepsia. 2017;58:S155. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosenberg EC, Louik J, Conway E, Devinsky O, Friedman D. Quality of life in childhood epilepsy in pediatric patients enrolled in a prospective, open‐label clinical study with cannabidiol. Epilepsia. 2017;58:e96–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeWolfe JL, Bebin EM, Cutter GR, et al. Effects of pharmaceutical grade cannabidiol on seizure frequency. American Epilepsy Society Abstracts Database (Abst. 2.100). Available from: https://www.aesnet.org/meetings_events/annual_meeting_abstracts/view/195499 Accessed May 7, 2018.

- 14. Gaston TE, Bebin EM, Cutter GR, Liu Y, Szaflarski JP, UAB CBD Program . Interactions between cannabidiol and commonly used antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2017;58:1586–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sommerville K, Crockett J, Blakey GE, Morrison G. Bidirectional drug‐drug interaction with coadministration of cannabidiol and clobazam in a phase 1 healthy volunteer trial. American Epilepsy Society Abstracts Database (Abst. 1.433). Available from: https://www.aesnet.org/meetings_events/annual_meeting_abstracts/view/381188 Accessed May 7, 2018.

- 16. Devinsky O, Patel AD, Thiele EA, et al. Randomized, dose‐ranging safety trial of cannabidiol in Dravet syndrome. Neurology. 2018;90:e1204–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grayson L, Vines B, Nichol K, Szaflarski JP, UAB CBD Program . An interaction between warfarin and cannabidiol, a case report. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2018;9:10–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials