Abstract

Although classical human astroviruses (HAstV) are known to be a leading cause of viral gastroenteritis, the pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of novel HAstV remain largely unknown. There is mounting evidence that, in contrast to classical astroviruses, novel HAstV exhibit tropism for the upper respiratory tract. This one‐year period prevalence screened all available clinical nasopharyngeal swab samples collected from pediatric patients aged ≤5 years for novel and classical HAstV using real‐time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. A total of 205 samples were tested; two novel HAstV cases were detected for a prevalence of 1.3%, with viral loads suggesting active upper respiratory tract replication. No classical HAstV was detected.

Keywords: novel astrovirus, pediatric, survey, tertiary care hospital, upper respiratory tract samples (URT)

1. INTRODUCTION

Classical and novel human astroviruses (HAstV) are nonenveloped, single‐stranded RNA viruses belonging to the Astroviridae family. Classical HAstV (serotypes 1‐8) are phylogenetically distant from novel HAstV (namely MLB and VA) with amino acid identities being as low as 23% to a maximum of 54.5% depending on the open reading frames.1 Although classical HAstV are a leading cause of viral gastroenteritis, especially in children, elderly, and immunocompromised patients,2, 3, 4 the clinical manifestations of novel HAstV have not been fully characterized.5, 6, 7, 8 The spectrum of human diseases for classical and novel HAstV is not restricted to the gastrointestinal tract: both have been reported as causal agents of central nervous system infections.1 A seroepidemiological study of the novel HAstV MLB1 in the United States suggests that primary infection occurs in childhood, with seropositivity reaching 70%, 90%, and 100% by ages 3, 4‐6, and 7‐17 years, respectively.9 A recent survey of classical and novel HAstV in clinical stool samples collected in a tertiary care hospital indicates that, for both viral groups, susceptible populations are young children (≤4 years) and the immunocompromised patients.10 Yet, for patients with novel HAstV, stool viral loads are lower and upper respiratory tract (URT) symptoms (cough, rhinorrhea, and odynophagia) are more frequent (70%), suggesting a potentially different pathogenic pathway between novel and classical HAstV. Indeed, additional reports of novel HAstV (MLB1, MLB2, and VA1) in pediatric nasopharyngeal specimens continue to emerge.11, 12, 13

Here, we report the results of a one‐year period‐prevalence survey of novel and classical HAstV in URT samples collected in pediatric patients in a tertiary care hospital in Switzerland and describe the case presentations of two novel HAstV‐positive patients.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Geneva (project # 2016‐01096).

2.2. Study design

In this retrospective single‐center cohort study, all clinical nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) samples collected at the University Hospitals of Geneva from ambulatory or hospitalized patients aged ≤5 years between 1 October 2016 and 30 September 2017 and with a sufficient leftover volume were analyzed by real‐time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT‐PCR). All NPS samples were collected as a part of routine clinical care to screen both influenza A/B viruses and respiratory syncytial viruses (RSV) A/B or a larger panel of respiratory viruses using the FTD FLU/HRSV and Respiratory pathogens 21 commercial assays (Fast Track Diagnostics, Sliema, Malta), respectively. Samples were collected in universal transport medium (UTM™) Viral Transport (Copan, Brescia, Italy) and stored at −80°C before analysis. Of note, the prevalence of novel and classical HAstV in URT samples was deliberately restricted to NPS samples to ensure that a sufficient leftover volume was available on the vast majority of cases after routine investigations.

2.3. rRT‐PCR screening

Each individual NPS specimen (380 μL) was spiked with 20 μL of a standardized canine distemper virus as previously described.14 Nucleic acids were extracted using the NucliSENS easyMAG (bioMérieux, Geneva, Switzerland) in 100 μL elution volume. Novel and classical HAstV were screened using a set of specific rRT‐PCR for MLB1‐3 and VA1‐4 as previously described.10 Data were analyzed with the StepOne software V.2 (Applied Biosystems, Rotkreuz, Switzerland).

Subjects #1 and #2 were screened for a large panel of respiratory viruses (human influenza A/B; rhinovirus; enterovirus; coronaviruses NL63, 229E, OC43, and HKU1; RSV A/B; parainfluenza 1‐4; metapneumoviruses A/B; parechovirus; adenovirus; and bocavirus) using the FTD respiratory pathogens 21 commercial assay. All additional available samples for subject #1 (stools on days 7 and 16, serum on day 0, and nasopharyngeal samples on days 16 and 27) were retrospectively screened for HAstV‐MLB2.

3. RESULTS

A total of 205 NPS collected from 156 individual patients (male‐to‐female ratio of 1.4:1) were screened for novel and classical HAstV by rRT‐PCR. The overall median age for samples collected was 17 months (range, 0‐71). The monthly distribution shows that NPS samples were collected homogeneously throughout the one‐year survey, with the exception of a major decrease during the months of July and August (Supporting Information Figure 1). Among the 205 NPS samples analyzed by rRT‐PCR, novel HAstV were detected in two samples: one case tested HAstV‐MLB2 positive (subject #1) and one HAstV‐MLB1 positive (subject # 2). The prevalence of novel HAstV was, thus, 1.3% (2/156). No sample was found positive for classical HAstV.

3.1. Subject #1: Clinical presentation

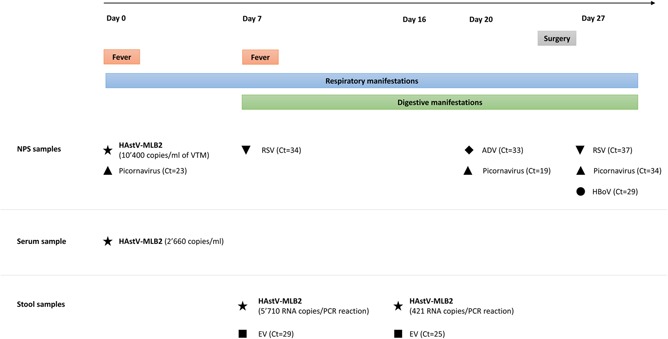

Figure 1 summarizes the patient’s clinical manifestations and microbiological findings. This 13‐month‐old female patient with a past medical history of congenital heart disease and severe failure to thrive was hospitalized electively for surgical repair of a ventricular septal defect on November 2016. At admission (day 0), the child presented with nasal discharge, fever (temperature of 38.4°C), and tachypnea (respiratory rate 44/minute) but normal oxygen saturation (97%). Laboratory workup revealed a normal white blood cell count and C‐reactive protein levels. Respiratory virus screening performed on an NPS sample revealed the presence of picornavirus (Ct = 23). A later analysis of the same sample revealed evidence of a novel HAstV‐MLB2 with a viral load of 10 400 RNA copies/mL of viral transport medium, as did the analysis of a serum sample collected on the same day (viral load to 2660 RNA copies/mL). A viral URT infection was diagnosed, and surgery was postponed. Of note, the retrospective review of the medical record provides no information on the presence of URT symptoms before admission. Subject #1 had no signs of gastrointestinal infection either before admission or on the day of sampling (day 0). Respiratory manifestations improved but persisted. On day 7, she presented with nonbloody diarrhea; stool samples were positive for enterovirus (Ct = 29) and novel HAstV‐MLB2 (5710 RNA copies/PCR reaction). Another NPS sample tested positive for RSV (Ct = 34). Because of continued gastrointestinal symptoms, an additional stool sample was collected on day 16; it revealed the continued presence of both enterovirus (Ct = 25) and novel HAstV‐MLB2 (421 RNA copies/PCR reaction). On day 20, a nasopharyngeal aspirate specimen tested positive for adenovirus (Ct = 33) and picornavirus (Ct = 19). Finally, a diagnosis of viral URT infection and acute viral gastroenteritis was made. The patient did not receive any antimicrobials and slowly improved, undergoing surgery on day 26. Although the patient remained asymptomatic, a postoperative bronchial aspirate sample was collected, given the earlier viral infections, and it revealed the presence of human bocavirus (Ct = 29), RSV (Ct = 37), and picornavirus (Ct = 34). The retrospective analysis for HAstV‐MLB2 was negative.

Figure 1.

Time frame of clinical manifestations and microbiological findings for subject #1. ADV, adenovirus; EV, enterovirus; HAstV‐MLB2, human astrovirus‐MLB2; HBoV, human bocavirus; NPS, nasopharyngeal swab; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; VTM, viral transport medium

The patient did not present any immediate postoperative complications.

3.2. Subject #2: Clinical presentation

A 21‐month‐old boy was hospitalized because of accidental second‐degree burns covering 10% of total body surface area. At the time of admission (day 0) in February 2017, he presented with coryza; oxygen saturation and temperature were within normal limits. The retrospective review of the medical record provides no information on the presence of URT symptoms before admission. Subject #2 had no signs of gastrointestinal infection before admission. The nasal discharge persisted, and on day 5 he became febrile (temperature 39.6°C) and tachypneic (respiratory rate 30‐38/minute); on auscultation, diffuse rhonchis were apparent, but oxygen saturation remained within normal limits. Skin examination revealed good wound healing without signs of infection. A chest X‐ray revealed no abnormalities. Laboratory workup showed normal C‐reactive protein and white blood cell count (9.3 G/L) with elevated bands (17%) and a mild lymphocytopenia (0.74 G/L). On day 6, the patient remained febrile (38.1°C) without diarrhea or other signs of focal infection apart from persistent coryza. An NPS sample tested negative for influenza A/B and RSV, but was retrospectively positive for picornavirus (Ct = 30) as well as a novel HAstV‐MLB1 (4380 RNA copies/mL of viral transport medium). In parallel, a rapid test performed on stool samples was positive for adenovirus. The diagnoses of viral URT infection and adenoviral acute gastroenteritis were made. The patient did not receive any antimicrobials, and by day 7, respiratory and gastrointestinal manifestations had been resolved.

4. DISCUSSION

This pilot study confirms that novel HAstV can be detected in URT samples among ≤5‐year‐old children with an estimated prevalence of 1.3%. This prevalence is likely an underestimation considering the relatively low number of URT samples collected at University Hospitals of Geneva in the summer season and the mild respiratory manifestations (cough and rhinorrhea, as previously reported10) for which children are often managed as outpatients and for which further diagnostic testing is rarely performed. Furthermore, a large number of rapid diagnostic tests for influenza A/B and RSV were conducted directly in the pediatric emergency room during the cold season, thereby limiting the number of URT samples sent to the routine laboratory for PCR screening. One hundred forty‐six of the 205 NPS samples (71.2%) were collected in the context of URT symptoms, while 55 (26.8%) were collected and screened for respiratory viruses in patients without URT manifestations but according to specific clinical situations (eg, fever of unknown origin, workup, follow‐up of transplanted recipients). For four NPS samples, the retrospective review of the medical records did not reveal any information about URT symptoms on the day of sampling.

The high HAstV‐MLB2 and ‐MLB1 viral loads estimated in NPS samples of subjects #1 and #2, respectively, support a local viral replication. Nevertheless, the causality of novel HAstV in upper respiratory manifestations cannot be concluded based solely on HAstV detection, particularly given the presence of multiple viral coinfections in these patients. The limitations of this pilot study to clarify the clinical relevance of novel HAstV in URT infections are: q(a) to extend the investigations to all susceptible populations, that is, pediatric and immunocompromised patients (b) although children ≤4 years represents the pediatric‐susceptible population, it would be relevant to perform a comparative analysis between the different pediatric age groups (ie, neonates, infants, children, and adolescent) (c) there is a need for prospective case‐control studies considering not only the novel HAstV susceptible populations but also the entire pediatric and adult populations with matching respective control groups. This would contribute to the estimation of asymptomatic carriage prevalence.

Subjects #1 and #2 both presented with upper respiratory manifestations followed by acute diarrhea, in line with the observations of a previous surveillance study.10 For subject #1, the detection of novel HAstV‐MLB2 in respiratory, serum, and stools samples confirms the presence of a disseminated infection. To date, most studies have reported disseminated infection only among immunocompromised patients.1 Subject #1 did not have a history, signs, or symptoms suggestive of immune deficiency. However, a certain degree of immunodeficiency cannot be ruled out because some heart diseases are associated with immune deficits in various syndrome.15 In particular, the underdiagnosed deletion 22q11, which may cause cardiac malformation and congenital immunodeficiency, was not investigated in this patient.16

The pathogenic pathways and clinical manifestations of novel HAstV require further characterization. The results obtained in this pilot study underline the need for further investigation using respiratory cell culture systems and prospective studies.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

SC and LK, Designed the study. LT, Performed the analysis. SC and MCZ, Analyzed the data. MCZ and NW, Reviewed the medical records. SC and MCZ, wrote the manuscript.

Supporting information

Supplementary Figure 1: Monthly distribution of the 205 nasopharyngeal swab samples screened. NPS: nasopharyngeal swab

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Gael Vieille (University Hospitals of Geneva) and Angela Huttner for technical and editorial assistance, respectively. This study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 310030_165873 to L Kaiser).

Cordey S, Zanella M‐C, Wagner N, Turin L, Kaiser L. Novel human astroviruses in pediatric respiratory samples: A one‐year survey in a Swiss tertiary care hospital. J Med Virol. 2018;90:1775–1778. 10.1002/jmv.25246

References

REFERENCES

- 1. Vu DL, Bosch A, Pintó RM, Guix S. Epidemiology of classic and novel human astrovirus: gastroenteritis and beyond. Viruses. 2017;9(2):1‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cortez V, Meliopoulos VA, Karlsson EA, Hargest V, Johnson C, Schultz‐Cherry S. Astrovirus biology and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Virol. 2017;4:327‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olortegui MP, Rouhani S, Yori PP, et al. Astrovirus infection and diarrhea in 8 countries. Pediatrics. 2017;141(1):e20171326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siqueira JAM, Oliveira DS, Carvalho TCN, et al. Astrovirus infection in hospitalized children: molecular, clinical and epidemiological features. J Clin Virol. 2017;94:79‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holtz LR, Bauer IK, Rajendran P, Kang G, Wang D. Astrovirus MLB1 is not associated with diarrhea in a cohort of Indian children. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khamrin P, Thongprachum A, Okitsu S, Hayakawa S, Maneekarn N, Ushijima H. Multiple astrovirus MLB1, MLB2, VA2 clades, and classic human astrovirus in children with acute gastroenteritis in Japan. J Med Virol. 2016;88:356‐360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meyer CT, Bauer IK, Antonio M, et al. Prevalence of classic, MLB‐clade and VA‐clade astroviruses in Kenya and The Gambia. Virol J. 2015;12:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xavier MPTP, Carvalho Costa FA, Rocha MS, et al. Surveillance of human astrovirus infection in Brazil: the first report of MLB1 astrovirus. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Holtz LR, Bauer IK, Jiang H, et al. Seroepidemiology of astrovirus MLB1. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014;21:908‐911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cordey S, Vu DL, Zanella MC, Turin L, Mamin A, Kaiser L. Novel and classical human astroviruses in stool and cerebrospinal fluid: comprehensive screening in a tertiary care hospital, Switzerland. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2017;6(9):e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cordey S, Brito F, Vu DL, et al. Astrovirus VA1 identified by next‐generation sequencing in a nasopharyngeal specimen of a febrile Tanzanian child with acute respiratory disease of unknown etiology. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5(9):e67‐e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sato M, Kuroda M, Kasai M, et al. Acute encephalopathy in an immunocompromised boy with astrovirus‐MLB1 infection detected by next generation sequencing. J Clin Virol. 2016;78:66‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wylie KM, Mihindukulasuriya KA, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Storch GA. Sequence analysis of the human virome in febrile and afebrile children. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e27735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schibler M, Yerly S, Vieille G, et al. Critical analysis of rhinovirus RNA load quantification by real‐time reverse transcription‐PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2868‐2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Radford DJ, Thong YH. The association between immunodeficiency and congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 1988;9:103‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pereira E, Marion R. Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Pediatr Rev. 2015;36:270‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Monthly distribution of the 205 nasopharyngeal swab samples screened. NPS: nasopharyngeal swab