Abstract

Context

Kaiser Permanente’s Care Management Institute created a screening tool, Your Current Life Situation (YCLS), which primarily is used to identify social needs for populations at risk of high health care utilization.

Objective

This frontline improvement project was designed to address key stakeholder concerns about implementing universal screening for social needs using the YCLS in a primary care clinic.

Methods

I conducted a rapid stakeholder analysis through informal conversations to identify the most important concerns. Four Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles were conducted to answer stakeholder questions and address concerns.

Results

Stakeholders expressed concerns including YCLS length and low screening acceptability and the possibility that too few or too many patients may have social needs. Throughout the project’s duration, 125 office visits occurred and 111 patients were screened. Among the patients for whom findings were positive, 27% requested help. Of the 14 patients who were not screened, only 1 patient opted out of screening. Practitioners and medical assistants stated that administration of the YCLS screening tool did not disrupt clinic workflow.

Conclusion

By using a frontline improvement approach, these investigators could answer questions and address concerns most important to local operational stakeholders when implementing screening for social needs. When practitioners conduct universal social needs screening and more fully understand social needs prevalence in a primary care clinic, resources can be tailored more effectively to accommodate patient needs.

Keywords: community resource specialist, front-line improvement, psychosocial issues, quality improvement, screening, social determinants of health

INTRODUCTION

Social and economic factors profoundly influence health and can affect up to 40% of health outcomes.1–3 Until recently, however, health care organizations rarely identified and addressed nonmedical factors because of financial incentives that led to an emphasis on procedure and visit volume rather than outcomes. With the enactment of the Affordable Care Act,4 value-based payment systems proliferated and prompted many health care systems to look beyond patients’ medical needs and address social determinants of health (“social needs”).5–6

The importance of addressing social needs has been established, but many health care systems lack clear guidance on ways to screen for and identify social needs.7 Despite the availability of multiple social needs screening tools,8 many health care practitioners do not routinely screen for social needs during primary care clinic encounters.9

Kaiser Permanente’s (KP) Care Management Institute (CMI) created a social needs screening tool, Your Current Life Situation (YCLS; see Sidebar: Your Current Life Situation (YCLS) Item Sources) through a process that included stakeholders within KP, public health researchers, and community-based organizations.10 The YCLS has been used in several KP Regions to identify social needs in populations at risk of high health care utilization, such as dual-eligible beneficiaries who qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid benefits, but it has not yet been used as a universal screening tool in primary care clinics. At KP Washington (KPWA, formerly Group Health), primary care clinics do not systematically screen, identify, and address social needs.

This frontline improvement project used minimal resources to address key stakeholder concerns regarding implementation of universal social needs screening using the YCLS in a primary care clinic. The intent was to gather as much data as necessary to increase confidence in the intervention and to help operational leaders make decisions.

METHODS

Context

Burien, WA, is a suburban community with a population of about 50,000. Median household income is $54,546, and about 17% of the population lives below the poverty line. Census records show the racial makeup of the city is 63.5% white (52% non-Hispanic white), 10.9% Asian, 7.6% two or more races, 6.4% African American, 1.6% American Indian, and 1.2% Pacific Islander.11

Group Health, and now as KPWA, has served Washington since 1947 and has more than 700,000 members throughout the state. The KPWA Burien Medical Center is a primary care clinic and a National Committee for Quality Assurance level 3 patient-centered medical home. The clinic has a patient panel of 21,295 with more than 30,000 office visits annually, and it houses a laboratory, pharmacy, Radiology Department, and short-term counseling services. The Medical Center staffs 6 residents, 12 family medicine physicians, 2 advanced practice practitioners, 1 pediatrician, and 1 general internist, and the support staff includes 3 nurses, 2 licensed practical nurses, 1 clinical pharmacist, and 1 licensed independent clinical social worker.

At KPWA primary care clinics including the Burien Medical Center, the social worker functions as an on-site behavioral health specialist to address mental health needs. S/he conducts psychosocial assessments, diagnoses mental health conditions, and provides short-term counseling to address substance-use disorders and behavioral health concerns.

Your Current Life Situation (YCLS) Item Sources.

Core YCLS Questionnaire items

Living situation: This is a Kaiser Permanente (KP)-created item that is a slight modification of a question on the Medicare Total Health Assessment.

Concerns about living situation: This is adapted from the Health Begins social needs assessment screening questionnaire.

Financial hardship: This is a KP-created item.

Food insecurity: This is the food insecurity item used by KP Colorado and Hunger Free Colorado.

Transportation: This is a slight adaptation of the transportation item from the PRAPARE Social Determinants of Health risk assessment.

Enough help with activities of daily living: The KP item has been created for the Medicare Total Health Assessment.

Help desired checklist: This is a KP-created item.

Who answered these questions: This was a KP-created question similar to the Medicare Total Health Assessment question used to document whether a member (or parent of child) provided the responses or someone else.

Supplemental/optional items that will be available in the YCLS Item Bank

Current marital/relationship status: This KP-created item is used to assess potential social support and people who possibly should be brought into the care plan. Note: There also is a field for marital status in the KP electronic medical record.

Educational attainment: This KP-created item is used to assess potential health literacy issues. The research shows that people with a high school education or less education are more likely to have difficulty understanding health information, instructions, etc.

Food insecurity (healthy food): These items are taken from California Medicaid Adult Stay Healthy Questionnaire.

Caregiver responsibilities: This is a KP-created item.

Trouble getting medications at the time needed: This KP-created item is modeled after the Institute of Medicine-recommended financial hardship question.

Instrumental social support (someone can call): This KP-created item also is used in the Medicare Total Health Assessment.

Health literacy: This Single Item Health Literacy Screening has shown to perform moderately well at ruling out limited reading ability in adults.2

Stress: This item is adapted from the 1998 NHIS Adult Prevention Supplement.

Interpersonal violence: This KP-created item is used to screen for intimate partner violence, caregiver abuse, and abuse or threats from someone else known to a person.

Loneliness/social isolation: This was modified from an item in the PROMIS Item Bank v 1.0-Emotional Distress-Anger-Short Form 1 and the AARP overall loneliness item from the AARP survey about loneliness in older adult.

Social connection: This item was taken from the PRAPARE SDOH assessment that combines the original Institute of Medicine–recommended Berkman-Syme Social Connection Index into 1 item.

Preventive dental care: This is a KP-created item.

Health confidence: This item was taken from the Dartmouth Primary Care Cooperative Research Network questionnaire.3

Financial abuse: This item was used in a KP Northern California Division of Research survey of high utilizers.

Overall rating of health: These items are from the PROMIS Global 10 scale and are also used in the Medicare Total Health Assessment.

Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics 2010 Jul;126(1):e26–32. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3146.

Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, Littenberg B. The Single Item Literacy Screener: Evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Family Practice 2006 Mar 24, 7:21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-7-21.

Wasson J, Coleman EA. Health confidence: An essential measure for patient engagement and better practice. Fam Pract Manag 2014 Sep–Oct;21(5):8–12.

AARP = American Association of Retired Persons; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey; PRAPARE = Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SDOH = social determinants of health.

Because the social worker’s responsibility at KPWA did not include addressing patients’ social needs, KPWA patients codesigned the community resource specialist (CRS) role in the Learning to Integrate Neighborhoods and Clinical Care project in 2012.12 The CRS addressed social needs by linking patients to community resources and internal organizational resources, helping patients set goals, and developing contacts in the local community. At the time of this project, KPWA had 2 CRSs staffed in 2 Medical Centers but no CRS at the Burien Medical Center. Consequently, the social worker at Burien Medical Center agreed to help address social needs identified through screening.

Stakeholder Identification

First, I conducted a rapid stakeholder analysis to identify people who had high interest in addressing social needs and power to effect change at Burien Medical Center.13 These stakeholders were a Burien Medical Center family medicine physician, the Burien Medical Center clinic manager, a KPWA Research Institute researcher, the KPWA behavioral health services manager, and the 2 CRSs. The KPWA behavioral health services manager also led implementation of the CRS role at KPWA.

Through one-on-one conversations, I informally interviewed stakeholders about implementing universal screening using the YCLS and using Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles to address questions and concerns. These questions and concerns were used to set the objective for the PDSA cycles.

The Survey

KP’s Care Management Institute created the 32-item comprehensive social needs screening tool, YCLS. They also created a brief 6-item questionnaire to assess these domains: Living situation, concerns about living situation, financial hardship, food insecurity, transportation, and help with activities of daily living. This form also included 2 questions to assess patients’ wanted help addressing their social needs and to document who answered the questions. The KP Care Management Institute defined the included domains and answers that resulted in a positive screening result on the YCLS. An additional “item bank” with questions from other domains was also available if practitioners, clinics, or organizations wish to tailor the tool for a specific purpose (see Appendix online at: www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2018/18-189-Suppl.pdf).

Plan-Do-Study-Act Cycles

The first PDSA cycle was conducted between July 24, 2017, and July 27, 2017, and the other PDSA cycles were conducted in 2-week increments between July 31, 2017, and August 14, 2017 (PDSA 2); August 28, 2017, and September 11, 2017 (PDSA 3); and September 25, 2017, and October 9, 2017 (PDSA 4). Patients were excluded from screening if they were non-English-speaking or had advanced dementia and no present caregiver. Caregivers completed forms for children younger than age 12 years. The objectives of each PDSA cycle are detailed in Table 1. During each cycle, universal screening was conducted on each practitioner’s patients using the screening process shown in Table 2. For all patients, the medical assistant (MA) obtained verbal informed consent, and patient anonymity was retained by removing all patient identifiers before collating data outside of the medical record.

Table 1.

Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle objectives and changes made following each cycle

| PDSA cycle | Objective | Changes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | To assess if the YCLS form can be used to screen for social needs in a primary care office visit without affecting standard workflow by screening all patients of Practitioner 1 between July 24, 2017, and July 27, 2017 | YCLS endorsed by stakeholders and local clinic staff; CRS in other medical centers to start using YCLS form for assessing referred patients |

| 2 | To understand prevalence of social needs at the Burien Medical Center by screening all patients of Practitioner 2 with the YCLS form between July 31, 2017, and August 14, 2017 | Changed “Debt” to “Debt causing financial distress” on YCLS form; added question regarding “social isolation” and “lack of access to healthy food” from the YCLS item bank to YCLS form for screening |

| 3 | To understand prevalence of social needs at the Burien Medical Center by screening all patients of Practitioner 2 with the modified YCLS form between August 28, 2017, and September 11, 2017 | Added question to YCLS form about desiring help to address social isolation |

| 4 | To understand prevalence of social needs at the Burien Medical Center by screening all patients of Practitioner 3, a practitioner with a higher number of patients on Medicare, with the modified YCLS form between August 28, 2017, and September 11 | Plans to incorporate YCLS into the EMR |

CRS = community resource specialist; EMR = electronic medical record; PDSA = Plan-Do-Study-Act; YCLS = Your Current Life Situation.

Table 2.

Universal screening process overview

| Step | Process |

|---|---|

| 1 | The dyad MA called the patient from the waiting room and roomed the patient according to standard clinic procedural process. |

| 2 | The MA used a script to describe the YCLS form and, with an opt-out process, explained the organization’s vision to care for the total health of the patient. |

| 3 | The MA exited the room and allowed the patient to self-administer the form. |

| 4 | The practitioner entered the room, acknowledged the responses, and, if results were positive, referred the patient to the CRS. If no CRS was available, the practitioner referred the patient to the social worker. |

| 5 | At the end of each PDSA cycle, the practitioner-MA dyad provided feedback regarding the process. |

| 6 | The feedback was reviewed and used to develop the aim for the subsequent PDSA cycle. |

CRS = community resource specialist; MA = medical assistant;

PDSA = Plan-Do-Study-Act; YCLS = Your Current Life Situation.

The MA handed the YCLS form to each patient after assisting patient to the exam room, obtaining vitals, reviewing their preventative care needs, and recording the data in the electronic medical record. The MA described the form and told patients they could opt out of screening if they desired, left the room, and allowed patients to self-administer the form. When the practitioner was ready for the clinical encounter, s/he entered the room and reviewed the completed form with the patient. The practitioner and MA did not alter their workflow; if any needs were identified, the practitioner referred the patient to the clinic’s social worker.

The Burien Medical Center’s family medicine physician (Practitioner 1, a key clinic stakeholder) conducted the first PDSA cycle. The second and third PDSA cycles were conducted on the patient panel of Practitioner 2, a family medicine resident physician. The fourth PDSA cycle was conducted on another family medicine physician’s panel (Practitioner 3) to address concerns raised during the third PDSA cycle. Practitioner panel data are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Each Practitioner’s panel size and patient characteristics

| Practitioner | Full-time equivalent adjusted panel size | Ages 0–18, no. (%) | Ages 19–64, no. (%) | Ages 65 and older, no. (%) | Medicare, no. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1868 | 206 (11%) | 1382(74%) | 280(15%) | 336 (18%) |

| 2 | 1594 | 143(9%) | 1307 (82%) | 144 (9%) | 159 (10%) |

| 3 | 1999 | 80 (4%) | 1339 (67%) | 580 (29%) | 640 (32%) |

Analysis

Measures were chosen to address the objective of each PDSA cycle and to add minimal burden to staff conducting cycles. For PDSA 1, the practitioner-MA dyad measured the number of incomplete YCLS forms at the time the practitioner entered the room. For all other PDSA cycles, the practitioner-MA dyad collected the completed YCLS forms and calculated the number of office visits, number and percentage of patients screened, number and percentage of positive screens, and number and percentage of patients requesting help. I collected the forms, collated the data without patient identifiers in Excel, and summarized the data in a PowerPoint presentation. I calculated the aggregated needs types that were identified during PDSA cycles 2 to 4 by percentage and elicited open-ended feedback from each practitioner in PDSA 1 and PDSA 4 and from each MA participating in all PDSA cycles about things that went well and needed improvement. I shared the results with the key stakeholders identified at the beginning of this project and used stakeholder feedback to create aims for subsequent cycles.

RESULTS

Stakeholder Concerns

During one-on-one conversations and group discussions, stakeholders expressed numerous concerns, including the YCLS form may be too lengthy to administer before a clinic visit and may disrupt the practitioner; patients may refuse to fill out forms assessing for social needs; too few patients may have social needs; and too many patients may have social needs.

The Burien Medical Center practitioner, identified as a key stakeholder at the beginning of the project, was concerned the YCLS form may be too long; she worried that if the form was intended to be self-administered after the patient was roomed, the patient could still be filling out the form when the practitioner reentered the room. In this instance, the practitioner might not have time to address the clinical agenda.

Although screening for social needs in primary care settings generally is associated with high levels of acceptability by patients (especially when screening is self-administered rather than during face-to-face contact),14–16 multiple stakeholders raised concern about low acceptability of social needs screening at KP because KP is a unique system that only serves insured members who may be of higher socioeconomic status and who refuse to fill out surveys about social needs.

Lastly, stakeholders said there were no data on the prevalence of social needs in the KP patient population and expressed concern. Few patients may have social needs, making screening “not worth it,” or many patients may have social needs and consequently “overwhelm the system.”

Social Needs Prevalence

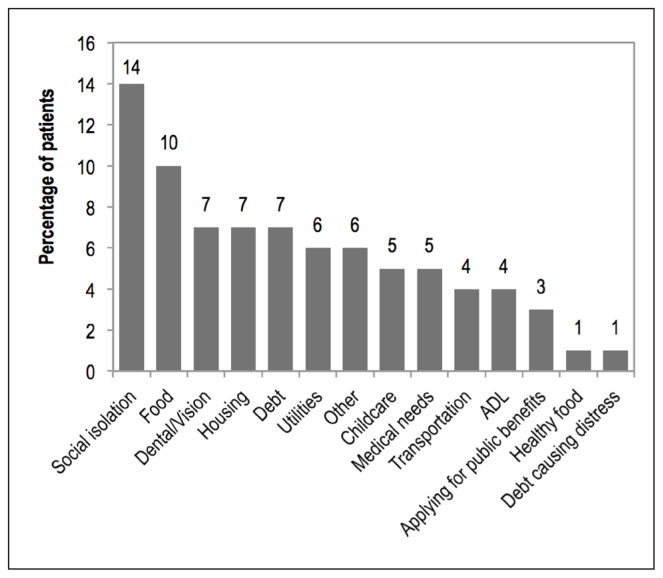

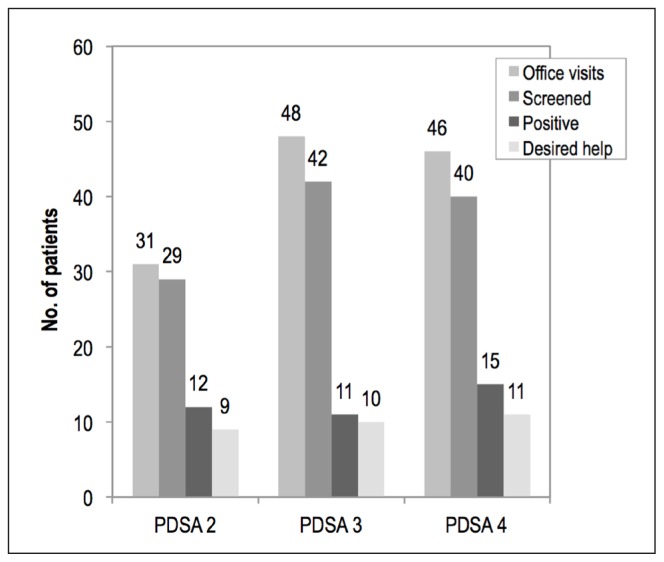

During the course of this project, 125 office visits occurred, 111 patients were screened, 38 patients screened positive for social needs, and 30 patients (27%) requested help to meet their social needs. Of the 14 patients who were not screened, only 1 patient opted out. All others were not screened by the medical team because of unintentional omissions of survey administration. The percentage of patients with positive screening findings who wanted help addressing their social needs during each PDSA cycle is illustrated in Figure 1. The aggregated types of needs identified during PDSA cycles 2 through 4 by number are shown in Figure 2. Although the question that screened for social isolation was added only during PDSA cycles 3 and 4, more patients screened positive for social isolation than any other need during this project.

Figure 1.

The types of needs by percentage of patients with positive screening findings who wanted help addressing their social needs.

ADL = activities of daily living.

Figure 2.

Aggregated need types identified during Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA)cycles 2 to 4.

Plan-Do-Study-Act Findings

During the first PDSA cycle, all of Practitioner 1’s patients were screened to determine if the YCLS was “too lengthy” and could not be completed before the beginning of an office visit. During the course of 2 days, 18 patients were screened and every patient was able to complete the YCLS form before the practitioner entered the room to begin the clinic visit. The practitioner stated that as long as the form was filled out before she entered the room, it did not affect her workflow; the MA also stated that the screening did not affect her standard workflow. These findings were disseminated to the stakeholders, which alleviated the concern that the YCLS could not be administered before an office visit. The CRS team reviewed the YCLS form and appreciated its structure. The team advised leadership to consider endorsing the form with the item bank for complete social needs evaluation of all referred patients at their home primary clinic.

The second PDSA cycle was conducted to better understand the prevalence of social needs in the clinic and to gauge screening acceptability. During the course of 2 weeks, 29 patients were screened, 12 patients had positive findings, and 9 (31%) requested help for the social needs identified. Those who requested help were referred to the social worker who contacted patients at a later time to address their needs. Also, 8 of the 9 patients screened positive for debt. The social worker believed that the positive screens for “debt” were false positives, however. Patients who screened positive for debt had reported student loan and mortgage payments that did not cause financial distress, so a revision to screening tool wording from “Debt” to “Debt causing financial distress” was suggested. The MA stated that employees at other clinics were enthusiastic after hearing about this work, which built momentum and energy around the project. The MAs requested that the forms be available for use outside of the project. These findings were disseminated to the clinic and shared with a larger stakeholder group at KPWA, including the manager for screening and outreach programs.

Two additional topics were identified by stakeholders who shared initial findings of Medicare’s Health Outcomes Survey, which showed a strong negative correlation between social isolation and health outcomes. A CRS reported underutilization of the Fresh Bucks Program, which provided electronic benefits transfer cardholders with funds to purchase fresh produce at participating markets. The feedback was acknowledged, the YCLS was modified, and 2 questions from the item bank were added to screen for social isolation and lack of access to healthy food.

The third PDSA cycle was conducted to better understand the prevalence of social needs in the clinic using the modified YCLS form and to gauge screening acceptability. During the course of 2 weeks, 42 patients were screened, 11 patients had positive results, and 10 patients (24%) requested help. After modifying question verbiage from “Debt” to “Debt causing financial distress,” only 1 patient screened positive for debt (28% during PDSA cycle 2 vs 2% during PDSA cycle 3). Seven patients screened positive for social isolation by stating that they “sometimes” or “often” felt socially isolated. The MA believed the screening was well received by patients and other staff members but also stated that the YCLS form did not provide an area in which to request help for social isolation. Findings were shared with the stakeholders, and the clinic manager contended that screening may work with Practitioner 1 and Practitioner 2’s panel but may not be feasible if a practitioner had a “more geriatric” panel. The clinic manager believed older patients may have more social needs and disrupt the clinic workflow. To address this concern, Practitioner 3 (a practitioner with a higher proportion of Medicare patients) was asked to participate in the fourth (final) PDSA cycle, which was conducted to better understand the prevalence of social needs in the clinic through use of the modified YCLS form.

During the course of 2 weeks, 40 patients were screened, 15 patients had positive results, and 11 patients (28%) requested help with needs identified. The percentage of office visits with Medicare patients was 46%. The dyad appreciated the structure with which to screen for social needs and felt it did not disrupt standard workflow. Practitioner 3 stated that the YCLS format made it difficult to scan the questionnaire before the clinic visit, understand needs, and customize care recommendations. She also shared that she enjoyed using the YCLS form to screen and identify social needs, which she had not done consistently during clinical encounters before the project launch. Findings were disseminated to stakeholders, and the clinic manager was reassured that universal screening for social needs could be conducted without disrupting clinic workflow.

DISCUSSION

During the course of this project, 111 of the clinic’s patients were screened using the YCLS form. Of the patients screened, 27% screened positive for a social need. Of the 14 patients not screened, only 1 patient opted out of screening.

Project findings addressed key stakeholder concerns. First, findings from the initial project phase demonstrated that the YCLS can be completed before a practitioner begins an office visit. Second, by using opt-out criteria for screening as a proxy for social acceptability, this project helped inform opinions about screening acceptability among the KP Burien Medical Center patient population. Although patients may have acquiesced, stakeholders and medical staff found it reassuring that they would not overwhelmingly refuse to participate in screening for social needs. Third, although the true prevalence of social needs in a primary care clinic patient population could not be ascertained with this project design, this work generated data that could serve as an anchor for discussions about whether there are too many or too few social needs in the KPWA Burien Medical Center population to justify the need for universal screening.

Universal screening for social needs was not continued at the end of this project because electronic medical record support was lacking. Integration of the survey into the electronic medical record and electronic tracking of who had already been screened and who needed to be screened was not achieved for several reasons. First, leadership had not achieved consensus on the best screening tool with which to identify patients’ social needs at KPWA. Multiple tools are currently being evaluated for social needs screening, including the Medicare Total Health Assessment,17 a survey that is offered to all KPWA Medicare Advantage members, and The Accountable Health Communities Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool created by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation.18 Second, the KPWA Information Technology team had already committed its resources to other projects and did not have the capacity to support this project. Lastly, during this project, KPWA implemented universal screening of all members for depression and alcohol use disorder to better integrate behavioral health care in the primary care clinic. This initiative took precedence over social needs screening because both depression and alcohol use disorder screening are endorsed by the US Preventive Services Task Force. Electronic medical record support for social needs screening likely can be built at KPWA after achieving consensus among leadership regarding the best screening tool for KPWA, confirming dedication of more information technology resources, and completing the behavioral health integration initiative.

Although this was not a primary clinic role, the social worker agreed to address the needs of patients who screened positive for a social need on the YCLS survey during this project. While the project was conducted, there were plans to expand the CRS role to all primary care clinics including the Burien Medical Center. The role of the CRS is to focus on addressing patients’ social needs by connecting them to internal organizational resources and external community resources, but the staffing ratio for the CRS was designed as only 1 CRS for every 20,000 patients. Because there was no universal screening for social needs and the demand for the CRS was unknown, the staffing ratio was determined at leadership’s discretion. By conducting more PDSA cycles and by better understanding the prevalence of social needs using universal screening, the CRS staffing ratio can be better tailored to match the demand of the primary care clinic.

This project’s strength was its ability to use minimal resources and existing workflows to rapidly address concerns of operational leaders. By using a frontline improvement approach, this project could focus on the psychology of change and combat skepticism of top-down initiatives. This was shown when Practitioner 3 shifted perspective on the possibility to address social needs in a primary care clinic, MAs requested that YCLS forms be used outside of the project, and CRSs endorsed use of YCLS in their social needs assessments.

The simplicity and the minimal costs and trade-offs associated with this project maximize its ability to be replicated in other contexts. Because this project was conducted within the KP system, it involved unique advantages that likely are not present in all organizations. Because of KP’s integrated health system model, financial incentives are aligned to address patients’ social needs, myriad stakeholders are accessible, and frontline innovation is valued.

Several project findings may help direct research, practice, and policy. The 6-item YCLS form was created with these domains: Living situation, concerns about living situation, financial hardship, food insecurity, transportation, and help with activities of daily living. During the PDSA iterations, several domains were added after receiving feedback from stakeholders. If universal screening is conducted, it is unclear which social needs domains should be included. Although ideally the domains would be chosen according to rigorous research findings demonstrating an ability to change outcomes, this research is not currently available. As the momentum of screening for and addressing social needs builds, it may be more feasible to choose screening domains that correlate with outcomes and measures valued by operational leaders.

CONCLUSION

This project focused on universal screening, but many organizations focus on screening patients at risk of high health care utilization because of cost savings. Cost savings are most apparent when treating populations at risk of high health care utilization because the decrease in inpatient, outpatient, and emergency services is most pronounced.19–20 Focusing only on cost savings subverts the competing priorities of a health organization such as KP, whose mission also consists of achieving health equity, providing appropriate clinical care, and acting as an anchor institution in a community. Referring ad hoc to community resource specialists or targeting only populations at risk of high health care utilization is an approach tainted by implicit and explicit bias, which leads to inequitable care. If an organization only targets high-risk individuals who often comprise the top 1% or 5% of high users, it would be likely that only a portion of the 27% of patients whose social needs were revealed in this project would be identified. This would undermine the ability of the care team to tailor care plans and decisions that take into account every patient’s social situation and would affect KP’s ability to understand its patient population and appropriately invest in the community. Universal screening is needed so organizations and clinics can best understand their patients’ social needs, leverage business finances, and align missions with the community to achieve better health.

Citizen Advocates

[Poverty] is basically a political problem, whose radical solution will require a return to distributive justice. Why write about it in a medical journal? Because doctors are also citizens; they have opportunities to observe and perhaps to mitigate the effects of poverty; and they should be, in Virchow’s words, “the natural advocate of the poor.”

— Douglas Andrew Kilgour Black, 1913–2002, Scottish physician and medical scientist who played a key role in the development of the National Health Service

Acknowledgment

Brenda Moss Feinberg, ELS, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995:80–94. doi: 10.2307/2626958. Spec No. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993 Nov 10;270(18):2207–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510180077038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Booske BC, Athens JK, Kindig DA, Park H, Remington PL. Different perspectives for assigning weights to determinants of health [Internet] Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute; 2010. Feb, [cited 2010 Dec 20]. Available from: www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/differentPerspectivesForAssigningWeightsToDeterminantsOfHealth.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachrach D, Pfister H, Wallis K, Lipson M. Addressing patients’ social needs: An emerging business case for provider investment [Internet] New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2014. May, [cited 2018 Aug 9]. Available from: www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2014_may_1749_bachrach_addressing_patients_social_needs_v2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraze T, Lewis VA, Rodriguez HP, Fisher ES. Housing, transportation, and food: How ACOs seek to improve population health by addressing nonmedical needs of patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016 Nov 1;35(11):2109–15. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Artiga S, Hinton E. Beyond health care: The role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity [Internet] Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. May, [cited 2018 Aug 24]. Available from: www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres J, De Marchis E, Fichtenberg C, Gottleib L. Identifying food insecurity in health care settings: A review of the evidence [Internet] San Francisco, CA: Social Interventions Research & Evaluation Network (SIREN); 2017. Nov 15, [cited 2018 Mar 23]. Available from: https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/sites/sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/files/SIREN_FoodInsecurity_Brief.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Screening tools [Internet] San Francisco, CA: Social Interventions Research & Evaluation Network (SIREN); c2018. [cited 2018 Mar 3]. Available from: https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/tools-resources/metrics-measures-instruments. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theiss J, Regenstein M. Facing the need: Screening practices for the social determinants of health. J Law Med Ethics. 2017 Sep;45(3):431–41. doi: 10.1177/1073110517737543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaForge K, Gold R, Cottrell E, et al. How 6 organizations developed tools and processes for social determinants of health screening in primary care: An overview J Ambul Care Manage 2018January/March4112–14. 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.QuickFacts: Burien city, Washington; King County, Washington; Washington [Internet] Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; [cited 2018 Apr 20]. Available from: www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/buriencitywashington,kingcountywashington,WA/RHI325216#viewtop. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu C. Adding a new role at clinics to help patients access community resources [Internet] Washington, DC: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; 2018. May, [cited 2018 Jun 8]. Available from: www.pcori.org/research-results/2012/adding-new-role-clinics-help-patients-access-community-resources. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brugha R, Varvasovszky Z. Stakeholder analysis: A review. Health Policy Plan. 2000 Sep;15(3):239–46. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottlieb L, Hessler D, Long D, Amaya A, Adler N. A randomized trial on screening for social determinants of health: The iScreen study. Pediatrics. 2014 Dec;134(6):e1611–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassan A, Blood EA, Pikcilingis A, et al. Youths’ health-related social problems: Concerns often overlooked during the medical visit. J Adolesc Health. 2013 Aug;53(2):265–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleegler EW, Lieu TA, Wise PH, Muret-Wagstaff S. Families’ health-related social problems and missed referral opportunities. Pediatrics. 2007 Jun;119(6):e1332–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Total health assessment questionnaire for Medicare members [Internet] Oakland, CA: Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc; 2014. Dec 5, [cited 2018 Jun8]. Available from: https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/sites/sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/files/MedicareTHA questionnaire v2 (rvd 12-5--14) with Sources.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billioux A, Verlander K, Anthony S, Alley D. Standardized screening for health-related social needs in clinical settings: The accountable health communities screening tool Discussion paper [Internet] Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2017. May 30, [cited 2018 Aug 9]. Available from: https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Standardized-Screening-for-Health-Related-Social-Needs-in-Clinical-Settings.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moffett ML, Kaufman A, Bazemore A. Community health workers bring cost savings to patient-centered medical homes. J Community Health. 2018 Feb;43(1):1–3. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0403-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan J, Abrams MK, Doty MM, Shah T, Schneider EC. How high-need patients experience health care in the United States: Findings from the 2016 Commonwealth Fund survey of high-need patients [Internet] New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2016. Dec 9, [cited 2018 Aug 9]. Available from: www.longtermcarescorecard.org/~/media/files/publications/issuebrief/2016/dec/1919_ryan_high_need_patient_experience_hnhc_survey_ib_v2.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]