Abstract

Traditionally, health care systems have addressed gaps in patients’ diet quality with programs that provide dietary counseling and education, without addressing food security. However, health care systems increasingly recognize the need to address food security to effectively support population health and the prevention and management of diet-sensitive chronic illnesses. Numerous health care systems have implemented screening programs to identify food insecurity in their patients and to refer them to community food resources to support food security. This article describes barriers encountered and lessons learned from implementation and expansion of the Kaiser Permanente Colorado’s clinical food insecurity screening and referral program, which operates in collaboration with a statewide organization (Hunger Free Colorado) to manage clinic-to-community referrals. The immediate goals of clinical screening interventions described in this article are to identify households experiencing food insecurity, to connect them to sustainable (federal) and emergency (community-based) food resources, to alleviate food insecurity, and to improve dietary quality. Additional goals are to improve health outcomes, to decrease health care utilization, to improve patient satisfaction, and to better engage patients in their care.

Keywords: community engagement, food insecurity, quality improvement, social determinants of health, social services

INTRODUCTION

Food insecurity, defined as unreliable access to adequate food caused by lack of money or other resources, is associated with poorer health, poorer diet quality (including reduced consumption of fruits and vegetables), a higher prevalence of chronic diseases, and higher health care costs.1–3 In the US, 12% of households experienced food insecurity in 2016, with particularly high rates in households with children, single parents, and low household income.4 Enrollment in federal food assistance programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), is associated with improved outcomes across multiple dimensions, including food security, nutrition, health, development, and health care costs.5–11 However, most health professionals have not been trained to assess food insecurity, and clinical algorithms to support nutrition education generally do not address food insecurity. Additionally, most health care systems lack standardized protocols or systems for referring food-insecure patients to federal or community-based programs that provide food resources.

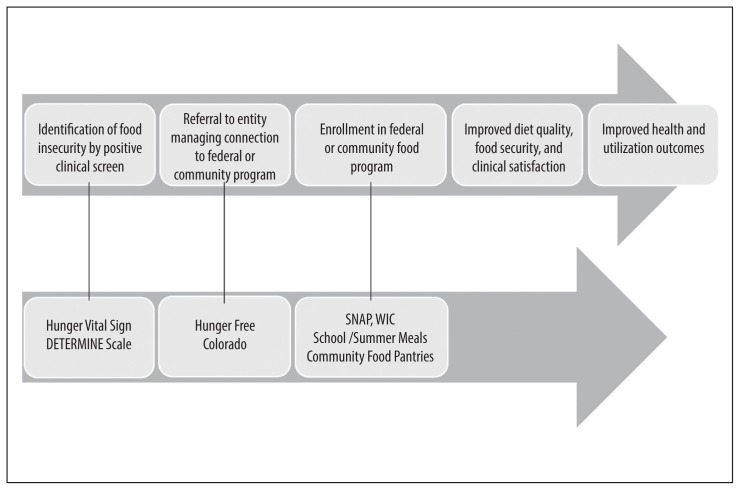

Despite these barriers, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Diabetes Association, and the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, among other professional organizations, have highlighted the clinical relevance of food insecurity through recommendations for food insecurity screening and referral to food resources.12–14 These guidelines exemplify broader efforts in the medical community to address social determinants of health because of their implications for prevention and management of chronic illnesses. In this article, we describe lessons learned from the Kaiser Permanente (KP) Colorado (KPCO) food insecurity pilot screening and referral program, designed with the intended goals of promoting food security and improving diet quality and health outcomes in KPCO and the community (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Processes and desired outcomes for the food insecurity screening program in Kaiser Permanente Colorado.a

a Upper arrow describes the general process of food insecurity screening programs and their intended outcomes. Bottom arrow describes the specifics of how these general processes were implemented at KPCO clinics.

KPCO = Kaiser Permanente Colorado; SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

When the pediatric food insecurity pilot began in 2011, the food insecurity rate in Colorado was 13.9% and in the US was 14.6%.15 Colorado ranked in the bottom 10 states nationally for participation in every federal nutrition program, including SNAP, the nation’s largest nutrition program.16 In response, KPCO, a health care organization with a patient population that includes 14% Medicare and 10% Medicaid beneficiaries, launched a food insecurity screening and referral program in 2 pediatric clinics. KPCO collaborated with a nonprofit advocacy and hunger relief organization, Hunger Free Colorado (HFC, www.hungerfreecolorado.org/), which was established in 2009 with funding from The Denver Foundation and KPCO. Hunger Free Colorado administers a statewide bilingual toll-free hotline, which provides a one-stop resource for Colorado residents to access federal and community-based food resources. Navigators at the hotline assess clients for eligibility to all federal nutrition assistance programs, submit applications to the county for those eligible for SNAP, and direct clients to other federal programs. In addition, they provide referrals to community organizations such as food pantries for emergency food resources. The data collected from the hotline informs HFC’s public policy agenda, which advocates for changes in food policy and systems, to reduce food insecurity in Colorado.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION AND LESSONS LEARNED

Screening Program to Identify Food Insecurity

Two pediatric clinics, 1 with 33% Medicaid beneficiaries and the other with 23% Medicaid beneficiaries, piloted the screening intervention. Because this operational program did not include human study subjects, the program was not reviewed by the KP institutional review board. At both pediatric clinic sites, parents were initially given a paper form at check-in with the Hunger Vital Sign screening tool. This 2-item assessment of food insecurity has high sensitivity and specificity and has been validated in households with children as well as in high-risk adult populations.17,18 The 2 items are as follows:

Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.

Within the past 12 months, the food we bought just didn’t last, and we didn’t have money to get more.

Parents were instructed to circle “often true,” “sometimes true,” or “never true” to each statement, with responses of “often true” or “sometimes true” to either question indicating food insecurity.

During the 3-month pilot, we learned that clinical teams were often unaware that food insecurity was prevalent in KPCO and that it contributed to reduced diet quality, poorer health outcomes, and increased health care utilization and expenses. Additionally, clinical teams lacked awareness of the availability of the SNAP and WIC nutrition programs, the types of support they provided, and their health benefits. Clinicians and staff were often uncomfortable discussing food insecurity with patients for fear it would feel stigmatizing to parents or raise parental concerns about being reported to social services.

Interventions to address these knowledge barriers included the development of educational handouts for clinicians and staff that described the following: Prevalence of food insecurity in households with children in Colorado, clinical manifestations of food insecurity, support provided by WIC and SNAP, validated food insecurity screening questions, and the referral process to HFC (Table 1). These handouts were distributed and discussed at departmental meetings. In addition, we presented case studies at departmental continuing medical education programs highlighting both food insecurity prevalence and its association with other health conditions.

Table 1.

Action steps and resources for food insecurity screening and referral programs

| Steps | Resources |

|---|---|

| Engage clinicians and staff |

|

| Screen for food insecurity |

|

| Refer to federal or community-based food support programs |

|

| Connect to food resources |

|

| Document in chart and analyze screening and referral data |

|

| Perform collaborative quality improvement |

|

| Improve outcomes |

|

CME = continuing medical education; EHR = electronic health record; HIPAA = Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

We also used multiple strategies to increase the comfort of clinicians and staff in talking with patients about food insecurity, attempting to reduce stigma associated with screening. We facilitated communication skill-building exercises to aid clinicians in conveying empathy to parents and supporting them in accepting referrals to food resources. We also provided written scripts, including one adapted from the WECARE survey19 that described motivation for screening: “Our goal is to provide the best possible care for your child and family. We would like to make sure that you know all the resources that are available to you for your problems. Many of these resources are free of charge.”

Data tracking in the pilot phase revealed that 18% of parents in the KPCO clinic with higher Medicaid enrollment and 12% of parents in the clinic with lower Medicaid enrollment lived in food-insecure households; these findings were much higher than anticipated by clinicians and staff at both clinics but were consistent with national data. The screening increased clinicians’ awareness of food insecurity among their patient population and reinforced the extent to which food insecurity was jeopardizing the prevention and treatment of many of their patients’ health conditions, including iron deficiency, obesity, failure to thrive, and school behavioral and attention concerns. As a result, these clinicians advocated for permanent integration of the Hunger Vital Sign into the standard well-child visit questionnaires. Other clinical systems have experienced a similar increase in support for food insecurity screening after pilot testing revealed the high clinical prevalence of food insecurity and of caregiver acceptability of screening.20–22 These observations demonstrate the extent to which clinical staff reluctance to screen for food insecurity out of concern that patients will feel stigmatized is unfounded.

Referral Processes

In the program’s initial implementation, a medical assistant handed parents reporting food insecurity a card with the phone number of the HFC Food Resource Hotline and instructed parents to call for support in accessing food resources. HFC tracks each referral and whether it results in a household member contacting the organization. Comparison of these data with data on the number of cards distributed from the clinic revealed that only 5% of households receiving the card called HFC for support in obtaining food services. This very low connection rate spurred the implementation team to develop a more active referral process. Instead of placing the burden on the parent to call the HFC hotline, parents were asked for permission to have an HFC representative call them to discuss food resources. For the clinic to share the necessary demographic information with HFC, parents needed to complete a brief consent, as required by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). We developed a semiautomated process to provide demographic information of parents reporting food insecurity to HFC by embedding an HFC referral form in the “letter” section of the electronic medical record. Demographic information was autopopulated into the letter, which was then printed and faxed to HFC.

After this change to an active referral that offered parents more support in accessing HFC, the percentage of referred parents who spoke with an HFC hotline navigator increased from 5% to 75%.23 Thus, as the food insecurity screening program was disseminated to other clinics and KPCO departments (described later), they adopted the same active referral model.

Despite its success, we encountered a few barriers in creating and sustaining the more active referral processes. First, we had to address both compliance and legal concerns to ensure we maintained patient confidentiality and adhered to all regulations and legal requirements.

Second, clinical teams spent valuable time printing and hand-faxing referrals to HFC. The subsequent formation of the KPCO community specialist team, with funding from KP primary care and community benefits, addressed this barrier. In this iteration of referral processes, when a food-insecure household is identified, the KPCO clinical staff send an electronic referral through the electronic medical record to the community specialist team, who then connects members with needed social resources. The community specialist team assesses household needs for a broad range of social support in addition to food, and faxes a referral to HFC. This new implementation model has advantages and disadvantages. Although it reduces the burden on the clinical team, it also adds an additional outreach step for patients. Survey results indicated that patients are confused by the multiple handoffs and outreaches, which potentially reduces the number of patients who ultimately connect with HFC. Continuous data tracking and quality improvement efforts are essential to understand practices that result in access to food resources and patient satisfaction.

Enrollment in Food Programs

When HFC connects with referred patients, it assesses eligibility for various federal and community resources available for food and then provides information about how to enroll in eligible programs. In the case of SNAP, HFC is also able to complete the SNAP application for the patient and to submit it to the administrative office of the county of residence. The ability to track the success of these referrals is critical to understanding the impact of the KPCO screening and referral program. Monthly, HFC provides reports to KPCO by secure information transfer. HFC provides data on whether referred households are interested in and eligible for SNAP, whether HFC submits a SNAP application to the county, and whether the application is approved.

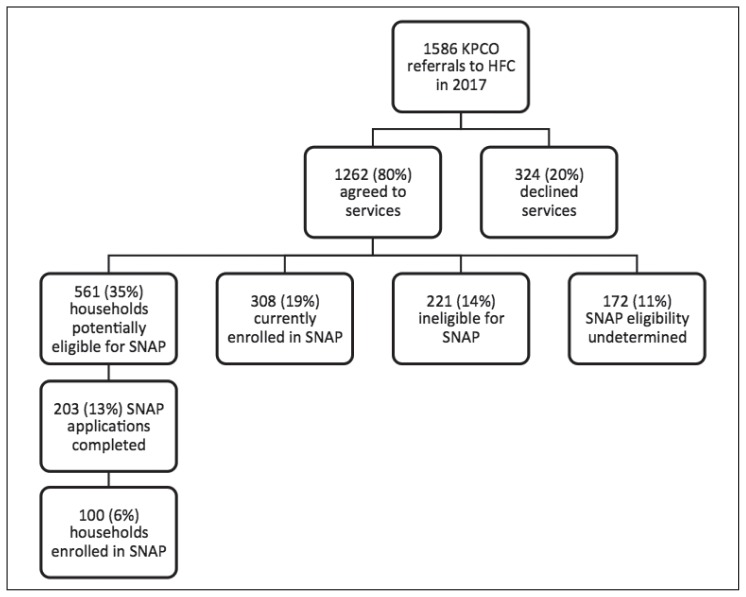

In 2017, approximately 6% of the 1586 referrals made from KPCO to HFC resulted in SNAP enrollment, presenting a clear opportunity for further quality improvement efforts for both KPCO and HFC. Increasing the 6% enrollment rate could be accomplished by KPCO referring patients most likely to be eligible for SNAP, including Medicaid beneficiaries not currently enrolled in SNAP, and by improving HFC follow-up of SNAP-eligible households that do not successfully enroll. Figure 2 illustrates the challenges of connecting patients to sustainable food resources. The 6% SNAP enrollment rate also emphasizes the importance of having referral processes in place to multiple food resources, not just SNAP. Additionally, HFC tracks referrals to other federal nutrition programs (eg, WIC) and community-based nutrition programs (eg, food pantries, summer meal programs, and home-delivered meals program). However, HFC is unable to track whether referrals to any of these programs are successful because of a lack of capacity to call clients back and a lack of data-sharing agreements (particularly with WIC).

Figure 2.

Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO) referrals to Hunger Free Colorado (HFC) resulting in household enrollment in SNAP, 2017.

SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Outcomes

Evaluators and researchers are in the process of assessing patients’ and clinicians’ satisfaction with screening; the time required for the screening and referral; and the impact of food security on diet quality, food security, health, and health care system utilization. KPCO is collaborating with HFC to administer a patient survey that assesses food resources received, changes in diet quality and food security, and satisfaction with the screening and referral processes. Analysis of these data is ongoing.

PROGRAM DISSEMINATION

Internal Dissemination

Awareness of food insecurity screening rose across the Pediatric Department with the distribution of handouts at departmental meetings highlighting population-specific impacts of food insecurity, validated screening questions, and referral processes to HFC; case studies of food-insecure patients at departmental continuing medical education programs; and communication skill-building activities during departmental meetings with a member of the community resource team and HFC hotline navigator. This experience in child health informed expansion of the food insecurity screening program to other KPCO departments. Expansion locations were determined by departmental capacity and enthusiasm for project implementation.

Clinical teams in the expansion locations had to determine how best to embed food insecurity screening into existing screening workflows, such as with health maintenance questionnaires, prenatal questionnaires, or intake assessments (for chronic disease managers and registered dietitians). In one case, the measurement tool was adapted to align with existing screening processes. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services requires health care systems that participate in the Medicare Advantage program to administer a Medicare Total Health Assessment to beneficiaries during an Annual Wellness Visit. The KPCO Medicare Total Health Assessment already included a single-item assessment of food insecurity as part of the DETERMINE nutritional risk assessment for older adults.24

Team composition also influenced the likelihood of adopting food insecurity screening and implementation processes. Teams with staff experienced in linking patients with social services, such as social workers, were more likely to embrace food insecurity screening. When a social worker was easily accessible, clinic staff were more accepting of screening and more confident that a referral to the social worker would result in patients receiving food. In contrast to the system set up by the pilot clinics, social workers referred food-insecure patients directly to HFC and personally followed up at subsequent appointments to ensure connection to food resources. Departments with embedded social workers had the highest number of HFC referrals.

This dissemination to other departments has highlighted the effort required to screen such a large number of KPCO patients, prompting a discussion about the possibility of using predictive modeling to target screening to certain high-risk population groups. For example, analysis of Medicare Total Health Assessment data from 50,097 older adults screened revealed an overall food insecurity rate that was relatively low at 5.7%, but with much higher risk among certain population subgroups (> 25% among dual Medicare-Medicaid enrollees and ≥ 10.0% among patients who are African American or Latino, or who have extreme obesity). Unfortunately, targeting only those high-risk groups for screening would have missed 50% of food-insecure older adults (those not in a high-risk group), suggesting that a universal screening approach may be necessary.25

Other efforts to decrease the burden of screening for food insecurity have focused on whether patients who are likely to qualify for SNAP benefits should be screened for food insecurity or screened for SNAP and WIC enrollment instead. Most Medicaid beneficiaries in Colorado are eligible for SNAP and WIC as well because of overlapping eligibility criteria (income eligibility for Medicaid is < 138% of the Federal Poverty Level; SNAP, < 200% of the poverty level; and WIC, < 185% of the poverty level). Rather than screen for food insecurity, Medicaid beneficiaries at KPCO will now be asked if they are enrolled in programs demonstrated to improve their health, including SNAP and WIC. Those who are not enrolled will be referred to HFC for SNAP enrollment or directly to WIC if the household includes a pregnant woman or child younger than age 5 years.

The adoption of different systems in different clinics for food insecurity screening and referral has also created challenges. As part of ongoing quality improvement, KPCO formed a community and clinic integration committee in 2018 to standardize and expand screening, referral, and charting processes across clinical departments; build communication skills across clinical departments; and maximize use of technology to facilitate information exchange between clinic and community organizations and to collect extractable data for evaluation. This committee includes clinicians, staff supervisors, community health representatives, and experts in information technology and evaluation, and it is coordinated by a program manager. This interdepartmental group crosses traditional reporting lines and functional responsibilities in KPCO. The group is exploring opportunities with community organizations to refine charting and data exchange processes and to leverage new funding models. The group is also expanding evaluation efforts to increase awareness of who is being screened for food insecurity and how many KPCO patients report being food insecure, particularly among vulnerable subgroups. The group recognizes that extractable social needs data could better inform decisions about the composition of clinical and complex care teams that can optimally address both medical and social needs.

External Dissemination

As part of its mission to improve the health of the broader community it serves and with its experience implementing and disseminating food insecurity screening and referral programs internally, KPCO in 2016 began providing grants and technical assistance to other health care systems caring for large numbers of Medicaid patients and interested in food insecurity screening. The screening protocol adopted by these systems included universal screening using the Hunger Vital Sign, recording of screening results into the electronic medical record, and automatic referral of patients screening positive to a community specialist, who then created the referral to HFC. Several of these systems improved on the KPCO approach by creating an automatically generated fax referral to HFC within the electronic medical record, which removed the barrier of hand-generating a referral or generating a semiautomated referral to be manually faxed. Because clinical staff recorded all screening results in the electronic medical record, screening rates and food insecurity rates could be easily tracked. The high rates of food insecurity that were identified motivated many health care systems to hire additional community specialist support.

Lessons learned in KPCO and in other health care systems involved in food insecurity screening throughout the state are shared during quarterly calls hosted by the Colorado Prevention Alliance and KPCO. Both HFC and the state WIC director participate in these calls, providing the leadership engagement necessary to leverage these calls to support continuous quality improvement. Current quality improvement efforts focus on improving referral processes, standardizing tracking measures across sites, and developing data sharing agreements to allow tracking of successful WIC referrals.

DISCUSSION

Deep engagement of KPCO in establishing systems for screening patients for food insecurity and referring food-insecure patients to federal and community food resources has fueled 3 initiatives. These initiatives are 1) targeted outreach to vulnerable subpopulations such as Medicaid enrollees, 2) an organizational standardization of screening and referral practices and processes to address food insecurity and other social determinants of health, and 3) a policy engagement strategy.

Evaluation of our processes and intermediate outcomes has created numerous process improvements, informed broad dissemination, and helped to build a business case for health care system funding of community organizations that successfully connect patients to food resources.

Advancing organizational, state, and federal policy to support food security, in partnership with other sectors, including business and government agencies, continues to be a priority. KPCO, other medical systems, and HFC are continuing engagement with partners across the state to implement the newly released Colorado Blueprint to End Hunger. In addition to food insecurity screening and referral programs, some medical systems in Colorado are using other strategies to improve food security and diet quality, including promoting fruit and vegetable incentives, developing hospital policies on local food procurement and food reuse, and connecting patients to medically tailored home-delivered meals. Ultimately, a better understanding of the impact of nutrition programs on health outcomes and health care utilization can inform changes in federal and state nutrition assistance policies, and may encourage Medicare and Medicaid to reimburse for screening and referral services.

Work to better identify food-insecure patients in clinical settings is occurring in the context of increased awareness of the need to identify patients with a range of social needs. Food insecurity often co-occurs with multiple other social needs, and understanding the patient’s prioritization of needs, and ideal composition of care teams needed to address social needs, will be essential to optimizing the clinical encounter for both the patient and the care team. Evaluation of models which are most effective at enrolling Medicaid beneficiaries in SNAP and WIC as well as models that successfully connect identified patients with SNAP, WIC, other federal nutrition programs, and other food resources is needed. KP’s Social Needs Network for Evaluation and Translation (SONNET, http://sonnet.kaiserpermanente.org/about-us.html) provides infrastructure for designing, implementing, evaluating, and disseminating heterogeneous social needs interventions within KP. Social needs evaluation has the potential to inform clinical process improvements and effective Medicaid, Medicare, and state and federal policies.

CONCLUSION

Health care systems can play an important role in supporting food security and improving diet quality by screening patients for food insecurity and connecting patients to a variety of food resources, including SNAP and WIC. However, processes for operationalizing these efforts are often poorly tested and inadequately supported by technology. Successful technologic solutions can promote bidirectional communication between clinics and state and community organizations; allow for data collection and tracking to inform process improvements and evaluate effectiveness; and streamline workflows. Health care systems can play a critical policy role in advocating for systems that use and integrate existing datasets, encourage enrollment in multiple benefits, and support access to community and federal food resources.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Nutrition and Obesity Policy Research and Evaluation Network’s (NOPREN) Hunger Safety Net Clinical Linkages Workgroup, funded by the Prevention Research Centers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Hanson KL, Connor LM. Food insecurity and dietary quality in US adults and children: A systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 Aug;100(2):684–92. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.084525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregory CA, Coleman-Jensen A. Economic research report number 235. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2017. Jul, Food insecurity, chronic disease, and health among working-age adults. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarasuk V, Cheng J, de Oliveira C, et al. Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. CMAJ. 2015 Oct 6;187(14):E429–36. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Economic research report number 237. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2017. Sep, Household food security in the United States in 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gregory CA, Deb P. Does SNAP improve your health? Food Policy. 2015 Jan;50:11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoynes H, Schanzenbach DW, Almond D. Long-run impacts of childhood access to the safety net. Am Econ Rev. 2016 Apr;106(4):903–34. doi: 10.1257/aer.20130375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black MM, Cutts DB, Frank DA, et al. Children’s Sentinel Nutritional Assessment Program Study Group. Special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children participation and infants’ growth and health: A multisite surveillance study. Pediatrics. 2004 Jul;114(1):169–76. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Rigdon J, Meigs JB, Basu S. Supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) participation and health care expenditures among low-income adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Nov 1;177(11):1642–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkowitz SA, Basu S, Meigs JB, Seligman HK. Food insecurity and health care expenditures in the United States, 2011–2013. Health Serv Res. 2018 Jun;53(3):1600–20. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson S, Keith-Jennings B. SNAP is linked with improved nutritional outcomes and lower health care costs [Internet] Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2018. Jan, [cited 2018 Jul 24]. Available from: www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-is-linked-with-improved-nutritional-outcomes-and-lower-health-care. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Food and Nutrition Service. Measuring the effect of supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) participation on food security [Internet] Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture; 2013. Aug, [cited 2018 Jul 24]. Available from: https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/Measuring2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strategies for Improving Care, The American Diabetes Association: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016 Jan;39(Supplement 1):S6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Council on Community Pediatrics; Committee on Nutrition. Promoting food security for all children. Pediatrics. 2015 Nov;136(5):e1431–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.A framework for Medicaid programs to address social determinants of health: Food insecurity and housing instability [Internet] Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2017. Dec 22, [cited 2018 Jul 24]. Available from: www.qualityforum.org/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=86907. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman-Jensen A, Nord M, Andrews M, Carlson S. Economic research report number 141. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2012. Sep, Household food security in the United States in 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Nutrition Service. Reaching those in need: State supplemental nutrition assistance program participation rates for 2011 [Internet] Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture; 2014. Feb, [updated 2018 Jan 12; cited 2018 Jul 24]. Available from: https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/Reaching2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010 Jul;126(1):e26–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gundersen C, Engelhard EE, Crumbaugh AS, Seligman HK. Brief assessment of food insecurity accurately identifies high-risk US adults. Public Health Nutr. 2017 Jun;20(8):1367–71. doi: 10.1017/s1368980017000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: A cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015 Feb;135(2):e296–304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palakshappa D, Vasan A, Khan S, Seifu L, Feudtner C, Fiks AG. Clinicians’ perceptions of screening for food insecurity in suburban pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2017 Jul;140(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0319. pii: e20170319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knowles M, Khan S, Palakshappa D, et al. Successes, challenges, and considerations for integrating referral into food insecurity screening in pediatric settings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018 Feb;29(1):181–91. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnidge E, LaBarge G, Krupsky K, Arthur J. Screening for food insecurity in pediatric clinical settings: Opportunities and barriers. J Community Health. 2017 Feb;42(1):51–7. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0229-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stenmark S, Solomon L, Allen-Davis J, Brozena C. Linking the clinical experience to community resources to address hunger in Colorado [Internet] Bethesda, MD: HealthAffairs; 2015. Jul 13, [cited 2018 Jul 20]. Available from: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/07/13/linking-the-clinical-experience-to-community-resources-to-address-hunger-in-colorado. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posner BM, Jette AM, Smith KW, Miller DR. Nutrition and health risks in the elderly: The nutrition screening initiative. Am J Public Health. 1993 Jul;83(7):972–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.7.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steiner JF, Stenmark SH, Sterrett AT, et al. Food insecurity in older adults in an integrated health care system. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018 May;66(5):1017–24. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]