Abstract

Background and aims

Delays in diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B virus infection (HBV) may be more common among underserved safety-net populations, contributing to more advanced disease at presentation. We aim to evaluate rates of and predictors of cirrhosis and cirrhosis-related complications among adults with chronic HBV.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated consecutive chronic HBV adults from gastroenterology clinics from July 2014 to May 2016 at a community-based safety-net hospital. Prevalence of cirrhosis or cirrhosis-related complications (ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)) at initial presentation was stratified by sex and race/ethnicity. Predictors of cirrhosis or cirrhosis-related complications at presentation were evaluated with multivariate logistic regression.

Results

Among 329 chronic HBV patients (mean age 49.1 years, 55.3% male, 66.5% Asian, 18.6% HBeAg positive) 27.7% had cirrhosis at presentation, 4.3% ascites, 3.7% variceal bleeding, 4.9% HE, and 4.0% HCC. Compared to women, men were more likely to have cirrhosis (34.6% vs. 19.1%, P < 0.01) and variceal bleeding (5.6% vs. 1.4%, P < 0.05) at presentation. On multivariate regression, older age at presentation (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01–1.07; P = 0.003) and positive HBeAg (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.20–5.51; P = 0.015) were associated with higher odds of cirrhosis at presentation, whereas men had a non-significant trend toward higher odds of cirrhosis (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 0.99–3.58; P = 0.055).

Conclusion

Among adults with chronic HBV at an ethnically diverse safety-net hospital system, nearly 30% of patients had cirrhosis at initial presentation, with the greatest risk seen among patients of male sex, older age, and with positive HBeAg.

Abbreviations: AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HE, hepatic encephalopathy

Keywords: viral hepatitis, disparities, linkage to care

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the leading cause of liver-disease related morbidity and mortality worldwide with over 250 million people living with the disease chronically.1 Currently, HBV can be prevented with vaccines and managed effectively with antiviral therapy, and early diagnosis of HBV through effective screening programs allows for timely initiation of therapy to prevent disease progression.2, 3 However, Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East has the greatest chronic HBV prevalence, where it is often transmitted vertically and therapies are not as readily available.4 In the United States, areas with higher rates of HBV are often associated with a larger immigrant population as well, contributing to the 1.25 million cases of HBV in the United States, though this may even be an underestimation.5, 6 Despite clear guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) for HBV screening and management, persistent lack of knowledge and awareness of HBV screening among primary care providers contributes to sub-optimal HBV care among the high risk populations.7, 8, 9 This sub-optimal care may contribute to delays in linkage to appropriate treatment, allowing disease progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Cirrhosis is a particularly worrisome consequence of HBV because it has additional complications associated including ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), and HCC. Nearly 40% of chronic HBV patients will develop cirrhosis or cirrhosis-related complications in their lifetime; however this risk can be mitigated with effective therapy aimed at viral suppression.3 The financial burden of cirrhosis was estimated to be $13 billion in the United States, emphasizing the importance of early preventative care to reduce the incidence of cirrhosis and its strain on the healthcare system.10, 11 Unfortunately, delays in HBV and cirrhosis diagnosis, which may be more common among underserved safety-net populations, contribute to more severe disease at presentation, which contributes to greater morbidity and mortality.7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14

Safety-net systems provide care to the indigent communities of the geographic region. The majority of patients served among safety-net systems either have no insurance or are underinsured. Among those that do have insurance, the majority are covered by Medicaid or other state-sponsored insurance plans. There is a high prevalence of ethnic minorities among safety-net systems and majority live at or below the national poverty level. Our current study aimed to evaluate rates of and predictors of cirrhosis and cirrhosis-related complications among adults with chronic HBV at first encounter with specialty care in an ethnically diverse, safety-net population.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated consecutive chronic HBV adults seen at gastroenterology clinics from July 2014 to May 2016 at a large community-based safety-net hospital system to determine the prevalence and predictors of cirrhosis and cirrhosis related complications (ascites, variceal bleeding, HE, or HCC) at initial presentation. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was determined through a thorough review of the electronic medical records and incorporated data from the clinical history from inpatient and outpatient chart notes, laboratory data, radiographic data, and liver biopsy data if available. Our diagnosis was not based on diagnosis coding or billing coding, but rather based on thorough chart review by a clinician to interpret and identify the diagnosis of cirrhosis. Thus the inclusion of cirrhosis on the problem list or discharge diagnoses by the treating provider was used to confirm presence of cirrhosis. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was determined in a similar fashion, such that we relied on the clinical notes, and if NAFLD was listed as a diagnosis, we considered the HBV patients to have concurrent NAFLD. In a similar fashion the presence of ascites, variceal bleeding, HE, and HCC was determined. For HCC in particular, the diagnosis relied on radiographic confirmation based on established AASLD criteria.

Overall patient demographics were stratified by sex and presented as proportions and frequencies or mean and standard deviation as appropriate. The prevalence of cirrhosis and cirrhosis-related complications at presentation were stratified by sex, race/ethnicity (Asian vs. non-Asian), HBeAg status (HBeAg positive vs. HBeAg negative) and evaluated with chi-square testing. Predictors of presenting with cirrhosis or cirrhosis-related complications at initial encounter were evaluated with multivariate logistic regression models. Variables chosen for inclusion in the multivariate model were selected a priori based on what we hypothesized to be clinically significant. The final multivariate model included age, sex, race/ethnicity, HBeAg status, and presence of concurrent nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical software package (version 13.0) and statistical significance was met with P-value < 0.05. This study was approved by Alameda Health System Institutional Review Board.

Results

Among 329 patients with chronic HBV included in the study, 55.3% (n = 182) were male and 66.5% (n = 218) identified as Asian race/ethnicity (Table 1). The average age of all the patients was 49.1 ± 13.1 years, and the average body mass index was 25.2 ± 6.2. 18.6% (n = 44) were HBeAg positive and 35.9% of patients had concurrent nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. 28.7% of chronic HBV had concurrent hypertension, 17.7% had concurrent diabetes mellitus, and 18.5% had concurrent metabolic syndrome. With the exception of age at time of presentation (males 50.8 years vs. females 46.9 years, P < 0.01), no significant sex-specific differences in patient characteristics were observed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Cohort.

| Variable | Overall |

Female |

Male |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion (%) | Frequency (N) | Proportion (%) | Frequency (N) | Proportion (%) | Frequency (N) | ||

| Female | 44.7% | 147 | |||||

| Male | 55.3% | 182 | |||||

| Asian | 66.5% | 218 | 68.7% | 101 | 64.8% | 179 | 0.46 |

| Non-Asian | 33.5% | 110 | 31.3% | 46 | 35.2% | 63 | |

| Age (mean, STD) | 49.1 | 13.1 | 46.9 | 14.1 | 50.8 | 11.8 | <0.01 |

| BMI (mean, STD) | 25.5 | 6.2 | 25.6 | 6.7 | 25.3 | 5.7 | 0.71 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 17.7% | 58 | 17.8% | 26 | 17.9% | 32 | 0.99 |

| Hypertension | 28.7% | 94 | 29.3% | 43 | 27.9% | 50 | 0.79 |

| Metabolic Syndrome | 18.5% | 60 | 17.9% | 26 | 19.1% | 34 | 0.79 |

| Concurrent NAFLD | 35.9% | 117 | 33.1% | 48 | 38.0% | 68 | 0.36 |

| Concurrent HCV | 10.2% | 14 | 15.0 | 9 | 6.5 | 5 | 0.10 |

| HBeAg positive | 18.6% | 44 | 15.1% | 16 | 21.7% | 28 | 0.20 |

| Anti-HBeAg Positivity | 81.4% | 192 | 84.9% | 90 | 78.3% | 101 | 0.34 |

| Laboratory values (mean, SD) | |||||||

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 141.1 | 445.0 | 139.6 | 476.7 | 51.9 | 424.6 | 0.97 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 156.6 | 516.8 | 158.0 | 562.4 | 155.5 | 485.8 | 0.98 |

| HBV DNA (IU/mL) | 15.5 million | 4.6 million | 14.9 million | 4.7 million | 16.0 million | 4.6 million | 0.84 |

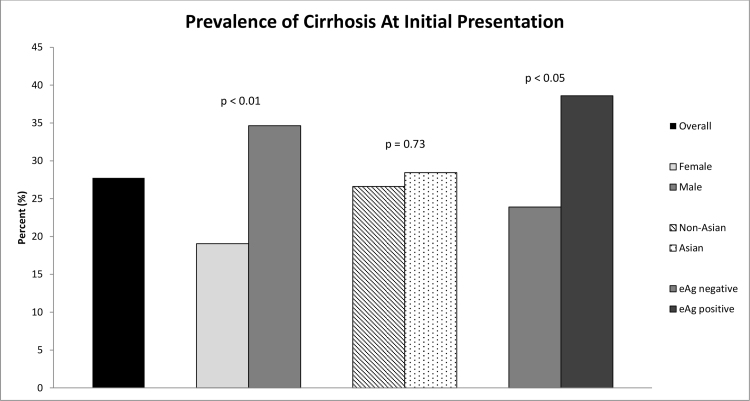

Overall, 27.7% of chronic HBV patients had evidence of cirrhosis at time of initial presentation (Figure 1). When stratified by sex, males were significantly more likely to have cirrhosis at presentation compared to females (34.6% vs 19.1%, P < 0.01) and males were also more likely to have variceal bleeding at presentation (5.6% vs 1.4%, P < 0.05) (Figure 1, Table 2). HBeAg positive patients were significantly more likely to have cirrhosis at presentation compared to HBeAg negative patients (38.6% vs 23.9%, P < 0.05). No significant difference in prevalence of cirrhosis was observed when comparing non-Asians vs Asians (Figure 1). No other significant differences in prevalence of cirrhosis-related complications such as ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, or hepatocellular carcinoma were observed (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of cirrhosis among HBV patients at initial presentation.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Cirrhosis and Cirrhosis-related Complications at Presentation.

| Overall | Female | Male | Non-Asian | Asian | HBeAg-neg | HBeAg-pos | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent (N) | Percent (N) | Percent (N) | Percent (N) | Percent (N) | Percent (N) | Percent (N) | |

| Cirrhosis | 27.7% (91) | 19.1% (28) | 34.6% (62)^ | 26.6% (29) | 28.4% (62) | 23.9% (46) | 38.6% (17)* |

| Ascites | 4.3% (14) | 2.1% (3) | 6.2% (11) | 6.5% (7) | 3.2% (7) | 2.6% (5) | 6.8% (3) |

| Variceal bleeding | 3.7% (12) | 1.4% (2) | 5.6% (10)* | 1.9% (2) | 4.6% (10) | 4.7% (9) | 2.3% (1) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 4.9% (16) | 2.8% (4) | 6.7% (12) | 3.7% (4) | 5.5% (12) | 4.2% (8) | 6.8% (3) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 4.0% (13) | 3.5% (5) | 3.9% (7) | 2.8% (3) | 4.6% (10) | 3.7% (7) | 2.3% (1) |

^P < 0.01.

P < 0.05.

On multivariate regression analysis, older age (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01–1.07; P = 0.003) and HBeAg positivity (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.20–5.51; P = 0.015) were associated with significantly higher odds of cirrhosis at initial presentation (Table 3). There was a non-significant trend toward higher odds of cirrhosis at presentation among males compared to females with chronic HBV (OR, 1.88; 95% CI 0.99–3.58; P = 0.055) (Table 3). When evaluating odds of cirrhosis-related complications at time of presentation, presence of cirrhosis was associated with significantly higher odds of ascites (OR, 21.87; 95% CI, 2.23–214.70; P = 0.008), variceal bleeding (OR, 33.59; 95% CI, 3.90–289.37; P = 0.001), HE (OR, 28.10; 95% CI, 3.39–232.91; P = 0.002), and HCC (OR, 24.62; 95% CI, 2.81–215.92; P = 0.004) at time of presentation. However, no other significant predictors of cirrhosis-related complications were observed.

Table 3.

Predictors of Cirrhosis and Cirrhosis-related Complications at Presentation.

| Cirrhosis | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (vs. female) | 1.88 | 0.99–3.58 | 0.055 |

| Asian (vs. non-Asian) | 0.92 | 0.44–1.91 | 0.82 |

| Concurrent NAFLD | 1.35 | 0.72–2.52 | 0.35 |

| Age | 1.04 | 1.01–1.07 | 0.003 |

| HBeAg positive | 2.57 | 1.20–5.51 | 0.015 |

| Ascites | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Variceal bleeding | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | 21.87 | 2.23–214.70 | 0.008 | Cirrhosis | 33.59 | 3.90–289.37 | 0.001 |

| Male (vs. female) | 3.90 | 0.43–35.63 | 0.23 | Male (vs. female) | 2.71 | 0.50–14.78 | 0.25 |

| Asian (vs. non-Asian) | 0.31 | 0.07–1.48 | 0.142 | Asian (vs. non-Asian) | 1.27 | 0.23–7.01 | 0.787 |

| Concurrent NAFLD | 1.25 | 0.27–5.87 | 0.776 | Concurrent NAFLD | 0.68 | 0.15–3.01 | 0.607 |

| Age | 0.97 | 0.90–1.04 | 0.386 | Age | 0.97 | 0.90–1.03 | 0.297 |

| HBeAg positive | 1.38 | 0.27–7.04 | 0.702 | HBeAg positive | 0.23 | 0.03–2.06 | 0.19 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Hepatocellular carcinoma | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | 28.10 | 3.39–232.91 | 0.002 | Male (vs. female) | 24.62 | 2.81–215.92 | 0.004 |

| Male (vs. female) | 2.48 | 0.47–12.94 | 0.283 | Male (vs. female) | 0.43 | 0.09–2.02 | 0.288 |

| Asian (vs. non-Asian) | 3.75 | 0.43–32.53 | 0.23 | Asian (vs. non-Asian) | 0.73 | 0.13–4.23 | 0.73 |

| Concurrent NAFLD | 0.92 | 0.23–3.63 | 0.906 | Concurrent NAFLD | 0.42 | 0.07–2.42 | 0.331 |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.94–1.06 | 0.95 | Age | 1.02 | 0.95–1.10 | 0.52 |

| HBeAg positive | 1.03 | 0.23–4.64 | 0.973 | HBeAg positive | 0.53 | 0.06–5.06 | 0.584 |

Discussion

Chronic HBV is a major contributor of chronic liver disease worldwide.4 While chronic HBV can be asymptomatic in early stages of infection, 15–40% of chronic HBV patients will develop cirrhosis or cirrhosis-related complications during their lifetime.15, 16 However, early detection through implementing effective screening programs allows timely evaluation and initiation of antiviral therapy to prevent disease progression. Delays in appropriate HBV screening and delays in referral to HBV care and treatment among newly diagnosed chronic HBV patients leads to more severe disease at presentation. We hypothesized that inherent barriers in linkage and access to care among chronic HBV patients to be especially impactful among safety-net populations.

Among a large urban safety-net hospital system, we observed that 27.7% of chronic HBV patients had cirrhosis at initial presentation to the gastroenterology services. These high rates of cirrhosis likely reflect multiple contributing factors. One significant factor may include lack of knowledge and awareness of guidelines regarding HBV screening and management among primary care providers that may contribute to delays in diagnosis and delays in referral to subspecialty care.7, 8, 9, 12, 17, 18, 19, 20 Specifically, recent studies evaluating primary care providers observed that over 40% of primary care providers self-reported being unfamiliar with AASLD guidelines for HBV preventative screening and management.7, 8, 9, 12 Additional studies observed that providers with higher patient load and perceived lack of specialty care resources were less likely to screen their patients for HBV, which is particularly relevant for those caring for patients in high-demand safety-net settings.9 For example, primary care providers among safety-net systems have been observed to screen for and vaccinate for HBV less than 65% of the time, including patients who are high risk,8, 9 and less than 20% of primary care providers offered proper HBV treatment.7, 12 These sub-optimal rates of screening and HBV management surely contribute to higher rates of HBV progression into cirrhosis.

Lack of health care access and delays in access to care are particularly important factors that affect healthcare outcomes among safety-net populations and may have contributed to the high rates of cirrhosis at presentation among our study's chronic HBV patients. Studies among 18 safety-net health care institutes observed that 55% of primary care providers perceived a shortage in specialists, whether it is because of lack of interest in working with the safety-net population or funding challenges for safety-net hospitals to hire specialists.21 As a result, appropriate and timely referrals may not be made, or even if referrals are submitted, it may take prolonged periods before patients are actually seen due to long wait times. In addition, a significant volume of patients who seek care from a safety-net hospital are on Medicaid or uninsured, of low socioeconomic status, and of underrepresented minorities. Based on a study performed on Massachusetts hospitals, up to 80% of patients who fall into the majority population characteristics of safety-net patients report delay of care, which impacts the quality of the care when they are seen by a physician.22, 23

Safety-net hospital systems are enriched in ethnic minorities, which is particularly important from the standpoint of chronic HBV given that ethnic minorities, specifically from Asia-Pacific and African regions, are at particularly high risk for chronic HBV infection. However, limited English proficiency or patient lack of knowledge and awareness of HBV can further contribute to delays in receipt of appropriate HBV screening and management. In a study among the immigrant community in New York, nearly 40% of were unable to correctly answer any questions about HBV transmission, symptoms, or consequences.17 Given that our study cohort includes a large immigrant population, lack of HBV awareness and its risks may have been important patient-specific factors contributing to poor follow up. Furthermore, safety-net systems continue to be enriched in uninsured or underinsured patients. Insurance status is particularly important given that uninsured patients have significantly more unmet needs compared to privately insured or Medicaid patients.24 Cost of care whether it was for travel or treatment is also a barrier to appropriate management of HBV, particularly for safety-net populations who already have inherent barriers in timely access to care.11

While our current study provides important data among an ethnically diverse community-based safety-net system, certain limitations should be acknowledged. Our current study focused on chronic HBV patients who were successfully linked to the gastroenterology service, and thus patients who have not been appropriately referred to or linked into the gastroenterology clinics were not captured. This raises two important concerns. Firstly, it could be argued that our rates of cirrhosis at presentation are high due to selection bias, namely that we are selecting out a population of HBV patients that have been referred to gastroenterology clinics, perhaps for management of advanced disease. However, within our safety-net system, it is the practice of primary care providers to refer HBV patients to gastroenterology clinics early on to help with initial evaluation and management, and not necessarily delaying referrals until advanced disease or complications. However, a second and very different perspective is such that our observed rates of cirrhosis among HBV patients are actually lower than the actual rates in our system, given that there are likely many chronic HBV patients either unaware of their infection status or who have not been successfully linked to gastroenterology clinic who already have or will develop cirrhosis. While we hypothesize this to be true, our current study cannot support this presumption. Furthermore, it is possible that our patients may have utilized multiple healthcare facilities during our study period, and may have already established subspecialty care prior to developing cirrhosis, thus overestimating the rates of cirrhosis at initial presentation. However, while our patients may have utilized emergency department resources at different facilities, our clinic is the only gastroenterology service that provides care in our safety-net system, thus ensuring that our assessment of linkage to subspecialty care for HBV is accurately captured. Our records do not accurate capture alcohol use, thus limiting our assessment of the impact of concurrent alcohol use on our outcomes. Furthermore, we acknowledge the possibility of additional risk factors and unmeasured confounders that were not included in our analyses due to limitations of availability of data that may have affected our study outcomes.

In conclusion, among adults with chronic HBV at an ethnically diverse safety-net hospital system, nearly 30% of patients had cirrhosis at initial presentation, with the greatest risk seen in older male patients. Given that safe and effective therapies for suppression of chronic HBV to prevent disease progression to cirrhosis and HCC exist, these observations highlight an important issue particularly among ethnically diverse safety-net systems, which carry a significant burden of the HBV infections in the U.S. More studies are needed to better identify provider-specific and patient-specific factors that contribute to sub-optimal HBV screening and management such that targeted interventions can improve HBV linkage to care and treatment.

Funding

Robert Wong is supported by an AASLD Foundation Clinical and Translational Research Award in Liver Diseases.

Conflicts of Interest

Robert Wong: consultant, advisory board, research grants, and speaker's bureau – Gilead. The other authors have none to declare.

Authors’ Contributions

Study concept and design: Tang, Wong.

Acquisition of data: Tang, Torres, Wong.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Tang, Torres, Liu, Baden, Bhuket, Wong.

Statistical analysis: Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: Tang, Wong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Tang, Torres, Liu, Baden, Bhuket, Wong.

Study supervision: Wong.

References

- 1.World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Global Hepatitis Report 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11(2):97–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terrault N.A., Bzowej N.H., Chang K.M. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2015 doi: 10.1002/hep.28156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schweitzer A., Horn J., Mikolajczyk R.T. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1546–1555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim W.R. Epidemiology of hepatitis B in the United States. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2009;49(5 suppl):S28–S34. doi: 10.1002/hep.22975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shepard C.W., Simard E.P., Finelli L. Hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and vaccination. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28:112–125. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxj009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burman B.E., Mukhtar N.A., Toy B.C. Hepatitis B management in vulnerable populations: gaps in disease monitoring and opportunities for improved care. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(1):46–56. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2870-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khalili M., Guy J., Yu A. Hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma screening among Asian Americans: survey of safety net healthcare providers. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(5):1516–1523. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1439-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukhtar N.A., Toy B.C., Burman B.E. Assessment of HBV preventive services in a medically underserved Asian and Pacific Islander population using provider and patient data. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(1):68–74. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3057-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grattagliano I., Ubaldi E., Bonfrate L. Management of liver cirrhosis between primary care and specialists. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2011;17(18):2273–2282. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i18.2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neff G.W., Duncan C.W., Schiff E.R. The current economic burden of cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7(10):661–671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukhtar N.A., Kathpalia P., Hilton J.F. Provider, patient, and practice factors shape hepatitis B prevention and management by primary care providers. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(7):626–631. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen T.T., McPhee S.J., Stewart S. Factors associated with hepatitis B testing among Vietnamese Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(7):694–700. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1285-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah S.A., Chen K., Marneni S. Hepatitis B awareness and knowledge in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive parturient immigrant women from West Africa in the Bronx, New York. J Immigr Minor Health/Center Minor Public Health. 2015;17(1):302–305. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9914-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chao D.T., Lim J.K., Ayoub W.S. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the proportion of chronic hepatitis B patients with normal alanine transaminase </=40 IU/L and significant hepatic fibrosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(4):349–358. doi: 10.1111/apt.12590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang C.M., Yau T.O., Yu J. Management of chronic hepatitis B infection: current treatment guidelines, challenges, and new developments. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2014;20(20):6262–6278. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i20.6262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bride M., Perumalswami P.V., Ly van Manh A. Assessing hepatitis B knowledge among immigrant communities in New York city. J Immigr Minor Health/Center Minor Public Health. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10903-017-0571-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caballero J.B., Martin M., Weir R.C. Hepatitis B prevention and care for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders at community health centers. J Health Care Poor Underserv. 2012;23(4):1547–1557. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu K.Q., Pan C.Q., Goodwin D. Barriers to screening for hepatitis B virus infection in Asian Americans. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(11):3163–3171. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1840-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor V.M., Bastani R., Burke N. Factors associated with hepatitis B testing among Cambodian American men and women. J Immigr Minor Health/Center Minor Public Health. 2012;14(1):30–38. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9536-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makaroun L.K., Bowman C., Duan K. Specialty care access in the safety net-the role of public hospitals and health systems. J Health Care Poor Underserv. 2017;28(1):566–581. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2017.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaskin D.J., Hadley J. Population characteristics of markets of safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals. J Urban Health. 1999;76(3):351–370. doi: 10.1007/BF02345673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weissman J.S., Stern R., Fielding S.L. Delayed access to health care: risk factors, reasons, and consequences. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(4):325–331. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-4-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hadley J., Cunningham P. Availability of safety net providers and access to care of uninsured persons. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(5):1527–1546. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]