Abstract

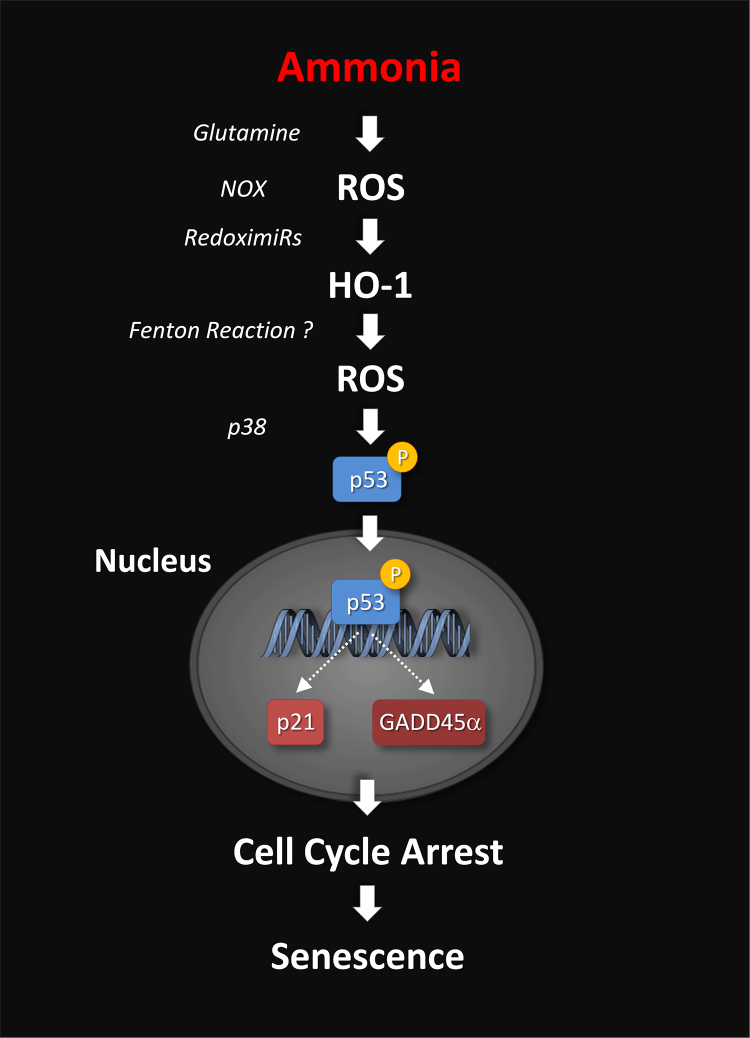

Hepatic Encephalopathy (HE) is a severe complication of acute or chronic liver diseases with a broad spectrum of neurological symptoms including motor disturbances and cognitive impairment of different severity. Contrary to former beliefs, a growing number of studies suggest that cognitive impairment may not fully reverse after an acute episode of overt HE in patients with liver cirrhosis. The reasons for persistent cognitive impairment in HE are currently unknown but recent observations raise the possibility that astrocyte senescence may play a role here. Astrocyte senescence is closely related to oxidative stress and correlate with irreversible cognitive decline in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. In line with this, surrogate marker for oxidative stress and senescence were upregulated in ammonia-exposed cultured astrocytes and in post mortem brain tissue from patients with liver cirrhosis with but not without HE. Ammonia-induced senescence in astrocytes involves glutamine synthesis-dependent formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), p53 activation and upregulation of cell cycle inhibitory factors p21 and GADD45α. More recent studies also suggest a role of ROS-induced downregulation of Heme Oxygenase (HO)1-targeting micro RNAs and upregulation of HO1 for ammonia-induced proliferation inhibition in cultured astrocytes.

Further studies are required to identify the precise sequence of events that lead to astrocyte senescence and to elucidate functional implications of senescence for cognitive performance in patients with liver cirrhosis and HE.

Abbreviations: ARE, Antioxidant Response Elements; BDNF, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor; Eph, Ephrine; EphR, Ephrine Receptor; GADD45α, Growth Arrest and DNA Damage Inducible 45α; GS, Glutamine Synthetase; HE, Hepatic Encephalopathy; HO1, Heme Oxygenase 1; LOLA, l-Ornithine-l-Aspartate; MAP, Mitogen Activated Protein Kinases; mPT, Mitochondrial Permeability Transition; NAPDH, Reduced Form of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate; nNOS, Neuronal-Type Nitric-Oxide Synthase; Nox, NADPH Oxidase; Nrf2, Nuclear Factor-Like 2; PBR, Peripheral-Type Benzodiazepine Receptor; PTN, Protein Tyrosine Nitration; RNOS, Reactive Nitrogen and Oxygen Species; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; SA-β-Gal, Senescence-Associated β-d-Galactosidase; TrkBT, Truncated Tyrosine Receptor Kinase B; TSP, Trombospondin; ZnPP, Zinc Protoporphyrin

Keywords: hepatic encephalopathy, astrocytes, ammonia, oxidative stress, miRNAs, heme oxygenase 1

Hepatic Encephalopathy (HE) is a frequent neuropsychiatric complication of acute and chronic liver diseases. Prominent symptoms of HE include motor disturbances such as ataxia and asterixis as well as intellectual deficits reflected by impaired learning ability and memory formation.1 In chronic liver disease clinical symptoms of HE are caused by a low grade cerebral edema which is accompanied by oxidative stress.2, 3 Osmotic and oxidative stress trigger multiple functional consequences in astrocytes which are suggested to disturb the communication between glia and neurons and oscillatory networks in the brain and thereby account for symptoms of HE.4

A very recent study identified premature senescence as another downstream consequence of ammonia-induced oxidative stress in astrocytes.5 Importantly, surrogate markers for both, oxidative stress and senescence were also upregulated in post mortem brain tissue from patients with liver cirrhosis with but not without HE.5, 6 As astrocyte senescence strongly correlates with irreversible cognitive decline in aging and neurodegenerative diseases, it was suggested that persistent cognitive impairment in patients with liver cirrhosis after resolution of an episode of overt HE7 may result from astrocyte senescence.5

The present review summarizes our current view on the role of senescence for the pathogenesis of HE in chronic liver failure.

Osmotic and Oxidative Stress in HE

By using 1H Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) pioneering work by Häussinger2 and confirmed by others8, 9, 10 consistently showed that the generation of a low-grade cerebral edema in patients with liver cirrhosis is a key event in the pathogenesis of HE. A more recent study confirmed these findings by directly quantifying the tissue water content in brain using magnetic resonance imaging.11 This study revealed brain region-specific changes in tissue water content which were significantly correlated with the severity of HE.11 However, a recent study found that treating patients with liver cirrhosis and minimal HE with l-Ornithine-l-Aspartate (LOLA) improved cognitive performance but had no effect on regional brain volume nor on cerebral osmolyte and glutamine levels.12 From these findings it was concluded that astrocyte swelling and brain volume changes are of no relevance for cognitive impairment in HE in chronic liver failure.12 Unfortunately, blood ammonia levels were not assessed in the study and the number of patients included in the study was relatively low. Therefore, the power of the study may be too low to detect significant changes.12

Astrocyte swelling per se triggers RNOS formation13, 14 and RNOS in turn induce astrocyte swelling.15 In line with this, HE-relevant factors such as ammonia, benzodiazepines and pro-inflammatory cytokines induce astrocyte swelling as well as the formation of Reactive Nitrogen and Oxygen Species (RNOS) in astrocytes.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Therefore it was postulated that HE-relevant factors engage a vicious cycle between osmotic and oxidative stress in astrocytes.21 RNOS sources in astrocytes include neuronal13, 17 and inducible16, 22 type nitric oxide synthases, NADPH Oxidase (Nox) 214 and mitochondria.5 Meanwhile, multiple functional consequences arising from the osmotic/oxidative stress response have been identified: Protein tyrosine residues become nitrated,14, 16 RNA is oxidized23 and gene expression and signaling are altered.13, 16, 24, 25, 26 Importantly, biomarkers for oxidative stress were also upregulated in post mortem brain samples from patients with liver cirrhosis and HE, but not those without HE.6, 25 Furthermore, the astrocytic protein glutamine synthetase was identified among the proteins that were nitrated in brain of patients with liver cirrhosis and HE.6 While this finding clearly indicates the presence of oxidative/nitrosative stress in astrocytes in brain of patients with liver cirrhosis and HE, it concurrently does not rule out, that also other cell types produce RNOS or are target of the deleterious actions of RNOS.6 This speculation is supported by studies on cultured brain cells showing that ammonia induces RNOS formation not only in astrocytes, but also in microglia,27 neurons24 and endothelial cells.28, 29 However, further research is required to decipher the functional consequences of RNOS formation in these cell types. Collectively, these studies univocally demonstrated that osmotic and oxidative stress are key factors in the pathogenesis of HE.

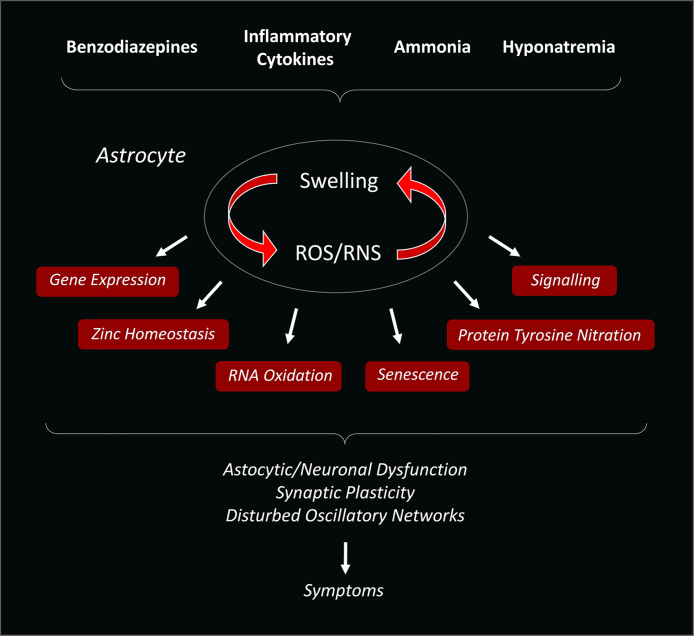

Most recent studies identified premature senescence as a novel functional consequence of ammonia-induced Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) formation in astrocytes.5 Importantly, enhanced expression levels of senescence biomarkers were also found in post mortem brain samples from patients with liver cirrhosis and HE but not in those without HE5 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathogenetic model of hepatic encephalopathy. Ammonia and other HE precipitating factors induce astrocyte swelling and oxidative stress which mutually amplify each other. This vicious cycle between osmotic and oxidative stress triggers various functional consequences such as nitration of tyrosine residues in proteins, oxidation of RNA, alterations of intracellular signaling pathways and gene expression and senescence. These changes impair the astrocytic/neuronal communication, neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity and disturb oscillatory networks in brain which is reflected by respective motor and cognitive symptoms (modified from [1]).

Oxidative Stress and Ammonia-Induced Astrocyte Senescence

The term senescence originally referred to the process of biological aging when it was discovered that aged cells lose the ability to replicate due to an arrest of the cell cycle. Therefore, senescence is a characteristic feature of normal brain aging30 but it is also observed in many neurodegenerative diseases.31 Importantly, senescence in brain and in particular in astrocytes strongly correlates with cerebral oxidative stress and a decline of cognitive functions.30, 31

Apart from an age-associated irreversible exhaustion of the replicatory potential, senescence may also be triggered by a variety of stressors such as RNOS, toxins or DNA-damage.32 This so-called “premature senescence” is in principle reversible upon removal of the triggering event.33

Recent studies showed, that ammonia, a main toxin in HE, inhibits the proliferation of cultured astrocytes in a dose-dependent5, 34 and reversible way5 probably due to an arrest in S-phase of the cell cycle.34 Importantly, ammonia also upregulates senescence-associated β-d-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal),5 which represents an established biomarker for senescence.33 Both, upregulation of SA-β-Gal and growth inhibition by ammonia are sensitive to inhibitors of glutamine synthetase and Nox which block ammonia-induced ROS formation in astrocytes.5, 20

The ammonia-induced ROS formation triggers phosphorylation of p53 at serine392 via mitogen activated protein kinases such as p38 (p38MAPK)35 and its nuclear accumulation.5 p53 is considered a master regulator of the cell cycle that can stall proliferation by activating the transcription of cell cycle inhibitory factors such as p21.36 In line with this, enhanced transcription of p21 and GADD45α as well as enhanced translation and nuclear accumulation of p21 were observed in ammonia-exposed astrocytes.5 However, whether further cell cycle inhibitory factors such as p15 or p1633 are also involved in ammonia-induced proliferation inhibition in astrocytes is currently unknown.

In line with the tight interdependence between osmotic and oxidative stress in astrocytes, also hypoosmolarity-induced astrocyte swelling triggers ROS formation14 and induces senescence37 in astrocytes. Currently, it remains unclear, whether apart from astrocytes, ammonia also induces senescence in other brain cells in HE.

Taken together, these studies established premature senescence in astrocytes as a new functional consequence of osmotic and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of HE.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Ammonia-Induced Astrocyte Senescence

Impaired energy metabolism and enhanced ROS formation in mitochondria strongly contribute to cerebral aging and senescence.33 In line with a role of mitochondrial dysfunction for senescence in HE, cell culture and animal studies suggest that ammonia impairs mitochondrial energy metabolism (for a review see [38]) and triggers ROS formation in mitochondria.5

The ammonia-induced mitochondrial dysfunction is also reflected at the structural level by fragmentation of the mitochondrial network and mitochondrial swelling.5, 39 Importantly, swelling of mitochondria in brain was also observed in animal models for chronic liver failure40, 41, 42 as well as in post mortem brain samples from patients with acute liver failure.43

Only little is known on the mechanisms that underlie mitochondrial dysfunction in HE. A number of studies suggested that glutamine mediates ammonia toxicity in mitochondria through a ROS-dependent and non-specific pore opening of the inner mitochondrial membrane (mitochondrial permeability transition, mPT).38, 44 Functional consequences of the mPT are a dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial swelling and apoptotic or necrotic cell death.37 Interestingly, ammonia induces the mPT45 and mitochondrial swelling5, 39 but does affect the vitality of astrocytes.5, 37 However, it remains to be established whether ammonia-induced swelling and fragmentation of mitochondria in astrocytes is a consequence of glutamine-mediated induction of the mPT. In this regard, results from studies on isolated brain mitochondria are inconsistent as to whether glutamine46 or ammonia per se47 induce mitochondrial swelling.

Besides ammonia, also ligands of the Peripheral-Type Benzodiazepine Receptor (PBR) induce the mPT and swelling of mitochondria.48 These findings raise the possibility that enhanced cerebral neurosteroid levels and increased benzodiazepine binding sites in brain of patients with liver cirrhosis and HE45 may further aggravate mitochondrial dysfunction and swelling.

HO1 and Ammonia-Induced Astrocyte Senescence

Heme Oxygenase (HO) is only weakly expressed in cultured brain cells and normal brain.49 However, HO1 mRNA and protein levels strongly increase in response to oxidative stress.49 In line with this, HO1 mRNA levels as well as oxidative stress markers are concordantly upregulated in ammonia-exposed astrocytes,37, 50 in brain in animal models for HE50, 51 and in post mortem brain samples of patients with liver cirrhosis with, but not without HE.25 However, it remains to be established in which cell types HO1 becomes upregulated in brain in patients with liver cirrhosis and HE. Interestingly, ammonia does not elevate the expression of HO1 in cultured neurons50 but in endothelial cells.28

ROS upregulate HO1 mRNA levels through activation of the transcription factor Nuclear Factor-Like (Nrf) 2, which binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) in the promoter region of the HO1 gene.52 So far, a role of Nrf2 for enhanced HO1 mRNA levels in experimental models of HE remains to be established but recent studies suggest an involvement of Micro RNAs (miRNA) in the ammonia-induced upregulation of HO1 mRNA in cultured astrocytes.37 In this regard, it was shown that ammonia elevates HO1 mRNA levels by downregulating a subset of HO1-targeting miRNAs in a NADPH oxidase-dependent manner. These miRNA species were identified to belong to the group of so called “redoximiRs”, as their expression levels are modulated by the intracellular redox status.37 Importantly, blocking HO1-targeting redoximiRs by selective miRNA inhibitors strongly upregulated HO1 mRNA and protein levels and concurrently inhibited astrocyte proliferation.37

In line with an important role of HO1 for ammonia-induced senescence further studies showed that blocking HO1 activity by tin protoporphyrin as well as inhibition of HO1 transcription by taurine fully prevented ammonia-induced astrocyte senescence.37 However, the mechanisms by which HO1 promotes astrocyte senescence are not understood and currently under investigation in our laboratories.

HO1-catalyzed heme degradation yields on the one hand redox active ferrous iron and on the other the antioxidant biliverdin and anti-inflammatory carbon monoxide.49 Therefore, HO1 can not only promote but also counteract oxidative stress. However, the factors that decide whether HO1 promotes pro- or anti-oxidative effects remain largely obscure. There is evidence indicating that HO1 promotes ROS formation in a ferrous iron-dependent way when it is constantly overexpressed in astrocytes.49

Whether HO1 triggers senescence in ammonia-exposed astrocytes through induction of oxidative stress is currently unclear and under investigation in our laboratories. Interestingly, a recent study showed that systemic application of the HO1 inhibitor Zinc Protoporphyrin (ZnPP) diminished oxidative stress and ameliorated behavioral abnormalities in brain of rats fed with an ammonium-containing diet.53 However, further studies are required to exclude that side effects of ZnPP account for the observed anti-oxidative effects in brain and normalization of behavior in hyperammonemic rats.53

Besides ammonia, also hypoosmolarity-induced astrocyte swelling triggers ROS formation,14 upregulation of HO137 and senescence37 in astrocytes. This again underlines the fundamental role of osmotic and oxidative stress in astrocytes for the pathogenesis of HE (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed signaling mechanisms underlying ammonia-induced senescence. Ammonia rapidly induces ROS formation and upregulates HO1 in a glutamine synthesis-dependent way. Downregulation of HO1-targeting miRNAs/redoxymiRs by ROS elevate HO1 mRNA and protein levels. HO1 may then contribute to ROS formation via promoting the Fenton reaction. ROS also upregulate the cell cycle inhibitory genes p21 and GADD45α and this involves p38-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear accumulation of p53. Subsequently, the cell cycle is arrested and astrocytes become senescent (modified from [5]).

Functional Consequences of Astrocyte Senescence in HE

Astrocytes control the maturation and the stability of synaptic connections through bidirectional communication with neurons.54 This communication is established through the release of growth factors and signaling molecules such as Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) or Thrombospondins (TSP)54 or by interaction of ephrins with corresponding ephrin receptors.55

However, in brain in normal aging and in neurodegenerative diseases astrocyte senescence is strongly associated with impaired neurotransmission and cognitive decline.30, 31 The mechanisms by which astrocyte senescence may disturb neurotransmission are not yet fully understood, but there is reason to assume that astrocyte senescence decreases synaptic connectivity. In line with this assumption, synaptic contacts were reduced in brains from different animal models for HE, as well as in ammonia-exposed astrocyte/neuron cocultures.56, 57 Importantly, the impaired synaptic connectivity in these HE models is associated with decreased BDNF56 and TSP57 levels. BDNF was shown to induce Tyrosine Receptor Kinase B (TrkBT)-dependent morphology changes in astrocytes at active synapses and this is suggested to stabilize synaptic contacts.58 In line with this, BDNF rapidly triggers filopodia outgrowth as well as actin polymerization in cultured astrocytes.5 However, BDNF-induced actin polymerization is completely abolished by ammonia in cultured astrocytes.5 This phenomenon may be explained by the observation that ammonia inhibits TrkBT N-glycosylation which may abolish TrkBT-mediated signaling.5 In line with this, inhibiting TrkBT N-glycosylation by tunicamycin also blocks BDNF-induced actin polymerization.5

Besides BDNF-dependent TrkBT signaling, also the interaction of Ephrins (Eph) with Ephrin-Receptors (EphR) on astrocytes and neurons at the tripartite synapse establishes and strengthens synaptic contacts.55 However, ammonia strongly changes the expression patterns of Eph and EphR isoforms and concurrently inhibits EphR4-dependent signaling in cultured astrocytes.59 Like the situation with TrkBT, impaired EphR4 signaling is associated with decreased N-glycosylation of the receptor and this may inhibit ligand-induced signaling.59 Importantly, Eph/EphR isoform expression changes were also observed in post mortem brain tissue of cirrhotic patients with HE.59

Therefore, one may speculate that ammonia-induced astrocyte senescence is associated with disturbed synaptic stability and connectivity by downregulating BDNF levels56 on the one hand and by blocking TrkBT-dependent BDNF-signaling on the other.5 Impaired ephrin/ephrin receptor signaling in senescent astrocytes may further decrease synaptic connectivity in brain.59 Thus, impaired astrocytic/neuronal communication and astrocyte senescence may induce permanent structural changes in brain in HE that may persist after resolution of an episode of overt HE. However, further work is needed to establish a role of astrocyte senescence for the disturbed astrocytic/neuronal communication in brain in HE.

Perspectives

Research over the past years univocally demonstrated a fundamental role of oxidative/nitrosative stress and related functional consequences for the pathogenesis of HE. This view was again strengthened by recent findings showing that ammonia induces astrocyte senescence in an oxidative stress dependent way. However, it remains to be established whether astrocyte senescence disturbs synaptic connectivity and accounts for persistence of cognitive impairment in cirrhotic patients after an overt episode of HE. Moreover, there is a lack of knowledge on the precise sequence of events that lead to astrocyte senescence.

In view of the fact that RNOS are important signaling molecules, it seems likely that a broad therapeutic intervention with antioxidants will have unpredictable side effects. Given the important role of HO1 for ammonia-induced astrocyte senescence, future studies may explore whether HO1 inhibition possesses therapeutic potential against persistent cognitive decline in patients with liver cirrhosis and HE.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgements

Our own studies reported in this article were supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through Collaborative Research Centers 575 “Experimental Hepatology” and 974 “Communication and Systems Relevance in Liver Injury and Regeneration”, (Düsseldorf). The authors are greatful to the Australian Brain Donor Programs NSW Tissue Resource Centre, which is supported by the University of Sydney, National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Schizophrenia Research Institute, National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and NSW Department of Health for tissue support.

Footnotes

For the special issue of Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology (JCEH) covering topics that were discussed at ISHEN 2017.

References

- 1.Häussinger D., Sies H. Hepatic encephalopathy: clinical aspects and pathogenetic concept. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2013;536:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Häussinger D., Laubenberger J., vom Dahl S. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies on human brain myo-inositol in hypo-osmolarity and hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1475–1480. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90552-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Häussinger D., Kircheis G., Fischer R., Schliess F., vom Dahl S. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: a clinical manifestation of astrocyte swelling and low-grade cerebral edema? J Hepatol. 2000;32:1035–1038. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Görg B., Schliess F., Häussinger D. Osmotic and oxidative/nitrosative stress in ammonia toxicity and hepatic encephalopathy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2013;536:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Görg B., Karababa A., Shafigullina A., Bidmon H.J., Häussinger D. Ammonia-induced senescence in cultured rat astrocytes and in human cerebral cortex in hepatic encephalopathy. Glia. 2015;63:37–50. doi: 10.1002/glia.22731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Görg B., Qvartskhava N., Bidmon H.J. Oxidative stress markers in the brain of patients with cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2010;52:256–265. doi: 10.1002/hep.23656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bajaj J.S., Schubert C.M., Heuman D.M. Persistence of cognitive impairment after resolution of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2332–2340. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordoba J., Alonso J., Rovira A. The development of low-grade cerebral edema in cirrhosis is supported by the evolution of (1)H-magnetic resonance abnormalities after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2001;35:598–604. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lodi R., Tonon C., Stracciari A. Diffusion MRI shows increased water apparent diffusion coefficient in the brains of cirrhotics. Neurology. 2004;62:762–766. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113796.30989.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kale R.A., Gupta R.K., Saraswat V.A. Demonstration of interstitial cerebral edema with diffusion tensor MR imaging in type C hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2006;43:698–706. doi: 10.1002/hep.21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah N.J., Neeb H., Kircheis G., Engels P., Haussinger D., Zilles K. Quantitative cerebral water content mapping in hepatic encephalopathy. Neuroimage. 2008;41:706–717. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McPhail M.J., Leech R., Grover V.P. Modulation of neural activation following treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Neurology. 2013;80:1041–1047. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruczek C., Görg B., Keitel V. Hypoosmotic swelling affects zinc homeostasis in cultured rat astrocytes. Glia. 2009;57:79–92. doi: 10.1002/glia.20737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schliess F., Foster N., Görg B., Reinehr R., Häussinger D. Hypoosmotic swelling increases protein tyrosine nitration in cultured rat astrocytes. Glia. 2004;47:21–29. doi: 10.1002/glia.20019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lachmann V., Görg B., Bidmon H.J., Keitel V., Häussinger D. Precipitants of hepatic encephalopathy induce rapid astrocyte swelling in an oxidative stress dependent manner. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2013;536:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schliess F., Görg B., Fischer R. Ammonia induces MK-801-sensitive nitration and phosphorylation of protein tyrosine residues in rat astrocytes. FASEB J. 2002;16:739–741. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0862fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Görg B., Foster N., Reinehr R. Benzodiazepine-induced protein tyrosine nitration in rat astrocytes. Hepatology. 2003;37:334–342. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Görg B., Bidmon H.J., Keitel V. Inflammatory cytokines induce protein tyrosine nitration in rat astrocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;449:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinehr R., Görg B., Becker S. Hypoosmotic swelling and ammonia increase oxidative stress by NADPH oxidase in cultured astrocytes and vital brain slices. Glia. 2007;55:758–771. doi: 10.1002/glia.20504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murthy C.R., Rama Rao K.V., Bai G., Norenberg M.D. Ammonia-induced production of free radicals in primary cultures of rat astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:282–288. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schliess F., Görg B., Häussinger D. Pathogenetic interplay between osmotic and oxidative stress: the hepatic encephalopathy paradigm. Biol Chem. 2006;387:1363–1370. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chastre A., Jiang W., Desjardins P., Butterworth R.F. Ammonia and proinflammatory cytokines modify expression of genes coding for astrocytic proteins implicated in brain edema in acute liver failure. Metab Brain Dis. 2010;25:17–21. doi: 10.1007/s11011-010-9185-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Görg B., Qvartskhava N., Keitel V. Ammonia induces RNA oxidation in cultured astrocytes and brain in vivo. Hepatology. 2008;48:567–579. doi: 10.1002/hep.22345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruczek C., Görg B., Keitel V., Bidmon H.J., Schliess F., Häussinger D. Ammonia increases nitric oxide, free Zn(2+), and metallothionein mRNA expression in cultured rat astrocytes. Biol Chem. 2011;392:1155–1165. doi: 10.1515/BC.2011.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Görg B., Bidmon H.J., Häussinger D. Gene expression profiling in the cerebral cortex of patients with cirrhosis with and without hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2013;57:2436–2447. doi: 10.1002/hep.26265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moriyama M., Jayakumar A.R., Tong X.Y., Norenberg M.D. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinases in the mechanism of oxidant-induced cell swelling in cultured astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:2450–2458. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zemtsova I., Görg B., Keitel V., Bidmon H.J., Schrör K., Häussinger D. Microglia activation in hepatic encephalopathy in rats and humans. Hepatology. 2011;54:204–215. doi: 10.1002/hep.24326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X.M., Peyton K.J., Durante W. Ammonia promotes endothelial cell survival via the heme oxygenase-1-mediated release of carbon monoxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;102:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jayakumar A.R., Tong X.Y., Ospel J., Norenberg M.D. Role of cerebral endothelial cells in the astrocyte swelling and brain edema associated with acute hepatic encephalopathy. Neuroscience. 2012;218:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagelhus E.A., Amiry-Moghaddam M., Bergersen L.H. The glia doctrine: addressing the role of glial cells in healthy brain ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 2013;134:449–459. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chinta S.J., Woods G., Rane A., Demaria M., Campisi J., Andersen J.K. Cellular senescence and the aging brain. Exp Gerontol. 2015;68:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Q.M. Replicative senescence and oxidant-induced premature senescence. Beyond the control of cell cycle checkpoints. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;908:111–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuilman T., Michaloglou C., Mooi W.J., Peeper D.S. The essence of senescence. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2463–2479. doi: 10.1101/gad.1971610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bodega G., Segura B., Ciordia S. Ammonia affects astroglial proliferation in culture. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0139619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panickar K.S., Jayakumar A.R., Rao K.V., Norenberg M.D. Ammonia-induced activation of p53 in cultured astrocytes: role in cell swelling and glutamate uptake. Neurochem Int. 2009;55:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thornton T.M., Rincon M. Non-classical p38 map kinase functions: cell cycle checkpoints and survival. Int J Biol Sci. 2009;5:44–51. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oenarto J., Karababa A., Castoldi M., Bidmon H.J., Görg B., Häussinger D. Ammonia-induced miRNA expression changes in cultured rat astrocytes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:18493. doi: 10.1038/srep18493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rama Rao K.V., Norenberg M.D. Brain energy metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction in acute and chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gregorios J.B., Mozes L.W., Norenberg M.D. Morphologic effects of ammonia on primary astrocyte cultures. II. Electron microscopic studies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1985;44:404–414. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198507000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dhanda S., Sunkaria A., Halder A., Sandhir R. Mitochondrial dysfunctions contribute to energy deficits in rodent model of hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-0136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laursen H., Diemer N.H. Morphometry of astrocyte and oligodendrocyte ultrastructure after portocaval anastomosis in the rat. Acta Neuropathol. 1980;51:65–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00688851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jamshidzadeh A., Heidari R., Abasvali M. Taurine treatment preserves brain and liver mitochondrial function in a rat model of fulminant hepatic failure and hyperammonemia. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;86:514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kato M., Hughes R.D., Keays R.T., Williams R. Electron microscopic study of brain capillaries in cerebral edema from fulminant hepatic failure. Hepatology. 1992;15:1060–1066. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albrecht J., Norenberg M.D. Glutamine: a Trojan horse in ammonia neurotoxicity. Hepatology. 2006;44:788–794. doi: 10.1002/hep.21357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butterworth R.F. Neurosteroids in hepatic encephalopathy: novel insights and new therapeutic opportunities. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;160:94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zieminska E., Dolinska M., Lazarewicz J.W., Albrecht J. Induction of permeability transition and swelling of rat brain mitochondria by glutamine. Neurotoxicology. 2000;21:295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niknahad H., Jamshidzadeh A., Heidari R., Zarei M., Ommati M.M. Ammonia-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and energy metabolism disturbances in isolated brain and liver mitochondria, and the effect of taurine administration: relevance to hepatic encephalopathy treatment. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;3:141–151. doi: 10.5114/ceh.2017.68833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chelli B., Falleni A., Salvetti F., Gremigni V., Lucacchini A., Martini C. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor ligands: mitochondrial permeability transition induction in rat cardiac tissue. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:695–705. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schipper H.M., Song W., Zukor H., Hascalovici J.R., Zeligman D. Heme oxygenase-1 and neurodegeneration: expanding frontiers of engagement. J Neurochem. 2009;110:469–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Warskulat U., Görg B., Bidmon H.J., Müller H.W., Schliess F., Häussinger D. Ammonia-induced heme oxygenase-1 expression in cultured rat astrocytes and rat brain in vivo. Glia. 2002;40:324–336. doi: 10.1002/glia.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song G., Dhodda V.K., Blei A.T., Dempsey R.J., Rao V.L. GeneChip analysis shows altered mRNA expression of transcripts of neurotransmitter and signal transduction pathways in the cerebral cortex of portacaval shunted rats. J Neurosci Res. 2002;68:730–737. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson J.A., Johnson D.A., Kraft A.D. The Nrf2-ARE pathway: an indicator and modulator of oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:61–69. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Q.M., Yin X.Y., Duan Z.J., Guo S.B., Sun X.Y. Role of the heme oxygenase/carbon monoxide pathway in the pathogenesis and prevention of hepatic encephalopathy. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:67–74. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chung W.S., Allen N.J., Eroglu C. Astrocytes control synapse formation, function, and elimination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7:a020370. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klein R. Bidirectional modulation of synaptic functions by Eph/ephrin signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:15–20. doi: 10.1038/nn.2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Galland F., Negri E., Da Re C. Hyperammonemia compromises glutamate metabolism and reduces BDNF in the rat hippocampus. Neurotoxicology. 2017;62:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jayakumar A.R., Tong X.Y., Curtis K.M. Decreased astrocytic thrombospondin-1 secretion after chronic ammonia treatment reduces the level of synaptic proteins: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Neurochem. 2014;131:333–347. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ohira K., Funatsu N., Homma K.J. Truncated TrkB-T1 regulates the morphology of neocortical layer I astrocytes in adult rat brain slices. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:406–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sobczyk K., Jördens M.S., Karababa A., Görg B., Häussinger D. Ephrin/Ephrin receptor expression in ammonia-treated rat astrocytes and in human cerebral cortex in hepatic encephalopathy. Neurochem Res. 2015;40:274–283. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1389-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]