Abstract

Since the discovery of the nervous system’s ability to produce steroid hormones, numerous studies have demonstrated their importance in modulating neuronal excitability. These central effects are mostly mediated through different ligand-gated receptor systems such as GABAA and NMDA, as well as voltage-dependent Ca2+ or K+ channels. Because these targets are also implicated in transmission of sensory information, it is not surprising that numerous studies have shown the analgesic properties of neurosteroids in various pain models. Physiological (nociceptive) pain has protective value for an organism by promoting survival in life-threatening conditions. However, more prolonged pain that results from dysfunction of nerves (neuropathic pain), and persists even after tissue injury has resolved, is one of the main reasons that patients seek medical attention. This review will focus mostly on the analgesic perspective of neurosteroids and their synthetic 5α and 5β analogs in nociceptive and neuropathic pain conditions.

Keywords: neurosteroids, chronic pain, T-channel (CaV3), T-channel calcium channel blockers, neurosteroid analogs, analgesic (activity)

Introduction

Since the discovery of steroid hormone synthesis in the rat nervous system (Corpechot et al., 1981), numerous studies have shown the pivotal role of steroid hormones in various neuronal functions, such as cognition, memory, affective disorders, neuroprotection, and myelination (Schumacher et al., 2012, 2014; Brinton, 2013; Giatti et al., 2015). These molecules are called neurosteroids, because they are produced in the nervous system by neurons and/or glial cells (Baulieu and Robel, 1990). Today, all steroid hormones that exert an effect on inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmission, regardless of their mechanism(s) and source (whether they are synthetic or endogenously produced), are considered neuroactive steroids (Paul and Purdy, 1992).

Neurosteroids are capable of modulating cell function on different levels. Conventionally, their effects are attributable to specific nuclear hormone receptors (e.g., progesterone) that regulate RNA expression. The onset of such effects is much slower, but the consequential changes may be long lasting. On the other hand, neurosteroids also exert their effects in the nervous system through modulation of various receptor systems and ionic channels (Baulieu et al., 1999; Mensah-Nyagan et al., 1999; Mellon and Griffin, 2002; Belelli and Lambert, 2005). Some of them, such as GABAA and NMDA receptors and/or voltage-dependent T-type Ca2+ or voltage-dependent K+ channels, are heavily implicated in sensory pathways responsible for mediating anesthesia and analgesia. The present review focuses on the role of neurosteroids in pain pathways, their potential as analgesics in different pain models, and future therapeutic perspectives.

The Role of Neurosteroids in Pain Pathways

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.” Although acute nociceptive pain has protective value for an organism, promoting survival in life-threatening conditions (Basbaum et al., 2009), prolonged pain that persists even after tissue injury has resolved is one of the main reasons that patients seek medical attention (Costigan et al., 2009).

Some of the first studies with intravenously injected cholesterol showed that steroid molecules could suppress painful information and decrease arousal by exerting an anesthetic-like state in mammals (Cashin and Moravek, 1927). In this study, abdominal surgery on cats was performed after intravenous (IV) administration of cholesterol, and animals were fully recovered. The pregnane class of steroids has become particularly important because of their allosteric modulation of neuronal GABAA receptors. Brot et al. (1997) showed that allopregnanolone mediates its anxiolytic effect by stimulating chloride flux through the channel of GABAA receptors via either binding sites different from the one for benzodiazepines, or via sites allosterically linked to the picrotoxin binding site. More recent studies have shown that neurosteroids are influencing the kinetics of synaptic GABAA-gated ion channels by prolonging the decay time of phasic responses, and therefore enhancing neuronal inhibition (Belelli and Lambert, 2005; Herd et al., 2007). Furthermore, neurosteroids also exert their effects via extrasynaptic GABAA receptors containing the δ-subunit, thus enabling tonic inhibition (Lambert et al., 2001). This effect was confirmed in a study of Stell et al. (2003) where tonic conductance was significantly reduced in mice lacking the δ-subunit of GABAA receptors, and was not influenced by 5α-pregnan-3α,21-diol-20-one (3α,5α-tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone,3α,5α-THDOC), a potent stereoselective positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor. The anxiolytic and anesthetic effects of 3α,5α-THDOC were attenuated in these mice (Mihalek et al., 1999). Altogether, these findings could explain the ability of neurosteroids to induce sedation and anesthesia in rodents.

Numerous clinical and animal studies have found that sex hormones can differentially regulate pain perception. For example, testosterone exerts analgesic effect in both humans and animal models, while estrogen can act both as an analgesic and hyperalgesic (Aloisi, 2003; Ceccarelli et al., 2003; Aloisi et al., 2004; Arendt-Nielsen et al., 2004; Aloisi and Bonifazi, 2006). It is well known that fluctuations of estrogen and progesterone during the estrous cycle can influence pain perception and pain threshold (Frye et al., 1992, 1993; Riley et al., 1998; Kuba and Quinones-Jenab, 2005). Furthermore, it seems that estrogen and progesterone may regulate the antinociceptive conformation of mu and kappa opioid receptor heterodimers (Chakrabarti et al., 2010), which makes them immensely important in pain regulation.

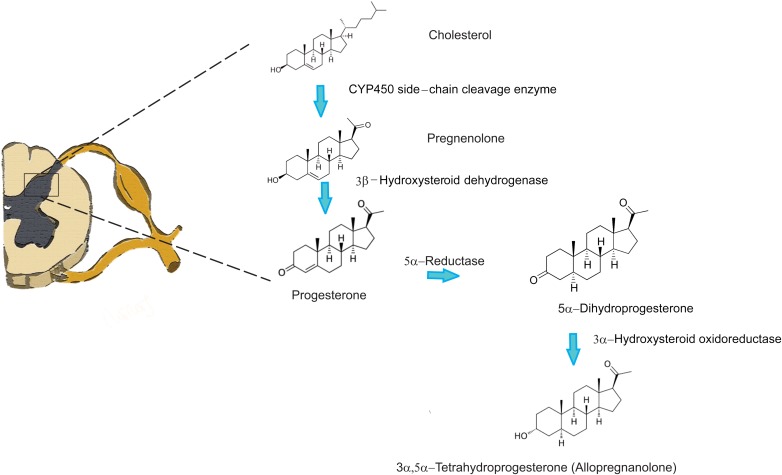

Several studies have confirmed the existence of particular enzymes involved in steroidogenesis throughout the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) (for review Baulieu and Robel, 1990; Compagnone and Mellon, 2000; Mensah-Nyagan et al., 2009). These compounds are crucial for plasticity of the nervous system (Patte-Mensah et al., 2006; Melcangi et al., 2008); therefore, they also play a very important role in pain perception and pain modulation. Interestingly, extensive studies on the dorsal horn region of the spinal cord have not been conducted. However, it is well known that the dorsal horn of the spinal cord plays a pivotal role in the transmission of painful stimuli from the peripheral nociceptors to supraspinal structures. It is also well established that primary afferent fibers coming from peripheral nociceptive neurons, whose cell bodies lie in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG), form synapses with the projection neurons of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. These neurons further convey information to the brainstem, thalamic, and cortical structures (Millan, 1999, 2002) that are able to modulate nociceptive transmission via several descending pathways at the level of the spinal cord. Because modulation of pain perception occurs at the level of dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord, it is not surprising that a particular set of enzymes, including a CYP450, involved in steroidogenesis was identified (Patte-Mensah et al., 2004; Mensah-Nyagan et al., 2008). An immunohistochemical study by Patte-Mensah et al. (2003) has confirmed that the highest density of these enzymes was detected in superficial layers of laminae I and II, where the first synapses between the nociceptive peripheral sensory neurons and projection neurons are located. Furthermore, homogenates of the rat spinal cord were capable of converting cholesterol into progesterone confirming that the enzymes are indeed functional. Locally synthetized progesterone in the spinal cord has also been shown to stimulate intrinsic spinal anti-nociceptive system via kappa and delta opioid receptors and promoting the increase of endorphins in situ (Dawson-Basoa and Gintzler, 1997, 1998). Additionally, there is evidence of direct inhibition of allopregnanolone synthesis in the dorsal horn with substance P, a potent pronociceptive neuropeptide (Patte-Mensah et al., 2005). This finding indicates that the presence of neuroactive steroids at the level of the dorsal horn could regulate GABA inhibitory tone, and that the pronociceptive effect of substance P released from primary afferents could be due to the reduction of GABAA receptor activity by downregulating the production of 3α, 5α-THP (allopregnanolone). These data strongly suggest that there is an active process of neurosteroid synthesis in the dorsal horn, particularly progesterone and allopregnanolone (two very potent analgesic neurosteroids) by direct enzymatic conversion (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Neurosteroid synthesis in the spinal cord from cholesterol.

Endogenous Neurosteroids and Pain

Recent studies suggest that progesterone and its derivatives, dihydroprogesterone (DHP) and 3α, 5α-tetrahydroprogesterone (THP) or allopregnanolone, have a specific neuroprotective action in the central and PNS (Guennoun et al., 2008, 2015; Melcangi et al., 2014; Schumacher et al., 2014). For example, these molecules are capable of exerting beneficial effects in pathological conditions such as traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury by promoting myelination and preserving white matter. In addition, endogenous neurosteroids show positive therapeutic effect in conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease (Irwin et al., 2014; Schumacher et al., 2014). Allopregnanolone, in particular, has been shown to promote neurogenesis by increasing neural progenitor proliferation of subgranular zone of dentate gyrus in adult 3xTgAD mice. Furthermore, in the same mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, allopregnanolone reversed the conditioned response/associative learning deficits of 3xTgAD mice to a level comparable to non-Tg mice (Wang et al., 2010). Furthermore, in allopregnanolone treated 3xTgAD mice, a significant reduction of β-amyloid production was noticeable (Chen et al., 2011). Allopregnanolone increased dopamine release from nucleus accumbens in freely moving rats (Rougé-Pont et al., 2002) and improved motor performance by promoting neurogenesis of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive neurons is substantia nigra (Adeosun et al., 2012) in the mouse model of Parkinson’s disease.

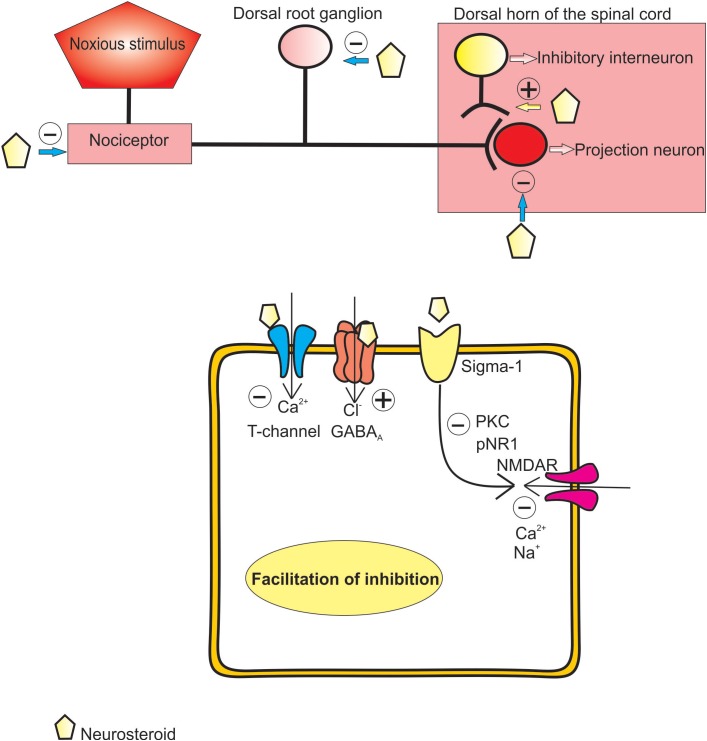

Numerous studies have also shown that steroids modulate pain sensitivity, either through intracellular/nuclear targets, or by modulation of synaptic transmission, both directly and indirectly via second-messenger systems. Potentiation of inhibitory GABA-ergic transmission in the pain pathway is one of the important mechanisms to diminish pain transmission (Zeilhofer et al., 2013). Predictably, analgesic potential of neuroactive steroids that promote GABA-mediated transmission in different pain paradigms is very well established.

Several other mechanisms are involved in analgesia induced by neurosteroids. It has been shown that progesterone, applied subcutaneously, successfully alleviated both mechanical and thermal allodynia in the sciatic nerve injury model, by preventing injury-induced increase of NR-1 subunit of NMDA receptors, as well as expression of PKCγ (Coronel et al., 2011). This reduction of PKCγ prevents the phosphorylation of NR1 subunit of NMDA receptors, which is crucial for receptor facilitation and contributes to the development of central sensitization. Antiallodynic effect of progesterone was also achieved in the spinal cord injury pain model (Coronel et al., 2014). The authors have shown that application of progesterone significantly reduced spinal expression of COX-2 and iNOS after spinal cord injury, revealing an anti-inflammatory activity of this endogenous neurosteroid that could contribute to its analgesic properties. Furthermore, the existence of receptors in dorsal horn neurons, sensitive to progesterone, supports the notion of the importance of neurosteroid induced modulation of pain processing (Labombarda et al., 2010). A particular type of receptor, sigma-1 receptor, a chaperone residing in endoplasmic reticulum, has recently been investigated as a potential target for progesterone binding in the spinal cord (Maurice et al., 2006; Monnet and Maurice, 2006; de la Puente et al., 2009). Sigma-1 receptors chaperon proper folding of nascent proteins. However, in certain conditions, such as binding of agonists, they could translocate to the cell membrane and interact with different G-protein coupled receptors and ionic channels. Previous studies have confirmed the presence of sigma-1 receptor in the dorsal horn neurons (de la Puente et al., 2009), as well as on DRG (Mavlyutov et al., 2016) which implicates them in the development of neuropathic pain and spinal sensitization after nerve injury. It has also been shown that activation of sigma-1 receptors leads to increased activity of PKC and PKA, which in turn induces phosphorylation of NR1 subunit of NMDA receptors, a process highly implicated in the development of central sensitization (Kim et al., 2008). Ortíz-Rentería et al. (2018) discovered that blocking sigma-1 receptors by progesterone leads to a significant decrease of TRPV1-dependent pain produced by capsaicin. Different authors have shown that treatment of sciatic nerve constriction and orofacial pain models with progesterone also successfully reduced mechanical and thermal allodynia (Dableh and Henry, 2011; Kim et al., 2012).

Of particular interest is dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), one of the first discovered neurosteroids (Baulieu et al., 1999). DHEA is found to be converted from pregnenolone by cytochrome P450c17 in the CNS. Although it can be found in human plasma, in rodents, plasma levels are extremely low, most likely since cytochrome P450c17 does not exist in rodent adrenals. However, DHEA synthesis exists in the spinal cord (Kibaly et al., 2005), a pivotal part of the sensory pathways, important for nociceptive transmission. Therefore, the importance of DHEA in modulation of pain perception should be considered. Kibaly et al. (2007) have found that when injected either peripherally (subcutaneous) or centrally (intrathecal), DHEA exerts pronociceptive effects by reducing the pain thresholds to painful stimuli. However, the repeated injections of DHEA exert a sustained analgesic effect. This indicates that DHEA exerts its acute algogenic effects most likely via either direct allosteric modulation of NMDA or P2X receptors, or via sigma-1 receptors, which in turn enhances phosphorylation of NR1 subunit of NMDA receptors (Yoon et al., 2010), leading to increased sensitization of pain pathways. On the other hand, delayed analgesic effect of DHEA could be explained by its metabolism to androgens in the spinal cord, such as testosterone, that exert analgesic effects (Kibaly et al., 2007).

Dehydroepiandrosterone seems to possess another feature, related to neuroprotection. A recent study of Lazaridis et al. (2011) indicated that DHEA prevented neuronal apoptosis by interacting with transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor TrkA. TrkA receptors are a known group of target receptors for the nerve growth factor (NGF). Via these receptors, NGF prevents cell apoptosis. Thus, the authors have discovered that, by binding to TrkA, DHEA exerts an antiapoptotic effect in HEK-293 cells, and reversal of apoptotic loss of TrkA positive sensory neurons in DRG of NGF null mouse embryos.

On the other hand, NGF/TrkA signaling pathway has already been implicated in pain transmission (Hirose et al., 2016). From the developmental standpoint, NGF is necessary during fetal period for normal growth of sensory nerve fibers belonging to pain pathways. However, during the adulthood, an NGF increase occurs during peripheral inflammation and nerve injury. This increase of peripheral NGF leads to the sensitization of surrounding nerves inducing pain, which is a protective response to prevent further tissue injury. But, if the inflammation and nociception persist, the protective value of increased NGF is lost leading to central and peripheral sensitization of pain pathways, and to the development of chronic pain states. This notion has been confirmed in the study by Ashraf et al. (2016) where an experimental compound has been utilized to antagonize effects of NGF via blocking the TrkA receptors, and therefore reducing pain and joint damage in rat models of inflammatory arthritis. Interestingly, a synthetic analog of DHEA, named BNN27, has been recently shown to interact with TrkA receptors (Pediaditakis et al., 2016) on DRG neurons without exerting pronociceptive behavior. This indicates a selective action against neurodegeneration but not influencing the pain pathways. Therefore, the rogue neurosteroid DHEA, and synthetic analogs, could have a more pleiotropic role, by simultaneously interacting with different receptor systems and hence, exerting different effects, that could be both beneficial and detrimental, depending on the activated pathways, age, and pathologies. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms of these dichotomous effects of DHEA in the pain pathway.

Progesterone’s metabolites, DHP and THP, have also been proven to act as analgesics in various pain models. For example, in the sciatic nerve crush injury model, progesterone and DHP successfully alleviated thermal nociception. This is possibly accomplished by restoring the thickness of the myelin and reducing the density of the fibers, as well as normalizing the function of Na+/K+-ATPase pump activity (Roglio et al., 2008). In chemically induced neuropathies, such as streptozotocin-induced diabetic neuropathy and chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, progesterone, allopregnanolone, and 5α-DHP have alleviated either thermal and/or mechanical nociception (Leonelli et al., 2007; Meyer et al., 2010, 2011).

Pathirathna et al. (2005b) have shown that allopregnanolone successfully alleviated mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in the neuropathic pain model of loose sciatic nerve ligation in rats by modulating both T-type Ca2+ channels (T-channels) and GABAA receptors. Specifically, allopregnanolone was a more potent analgesic than its analogs, which only inhibited T-channels or potentiated GABAA-gated currents.

Additionally, Ayoola et al. (2014) have found that local paw injections of epipregnanolone, an endogenous 5β-reduced neurosteroid without potentiating effects at GABAA receptors, successfully alleviated mechanical and thermal sensitivity in both wild-type mice and rats, but not in CaV3.2 T-type calcium channel knock-out mice. This suggests that the antinociceptive effect of epipregnanolone is mediated largely by inhibition of T-channels in peripheral nociceptors.

Taken together, these data strongly suggest that endogenously produced neuroactive steroids are very potent analgesics in different pain models, and that they exert their analgesic effects via various receptor systems and ion channels, most notably GABAA receptors and T-type calcium channels (Figure 2). On one hand, their ability to evoke effects through different receptor systems, either directly or through second-messenger systems, makes them an excellent alternative to conventional therapeutic options for treating various pain states. On the other hand, drugs that target so many receptor systems often produce various adverse events in humans. Therefore, creating a potent, but more selective, neuroactive steroid would be a focus of future studies of these interesting compounds.

FIGURE 2.

Proposed mechanisms of analgesic effect of endogenous and synthetic neurosteroids.

Analgesic Properties of 5α- and 5β-Reduced Steroid Analogs

The role of GABAA receptors as the main inhibitory receptors in pain pathways is well established (Millan, 1999); however, the role of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) has not been explored as thoroughly. Based upon the membrane potential that activates them, VGCCs can be divided into two categories: high-voltage-activated (HVA) and low-voltage-activated T-type Ca2+ channels. Of interest for this review are T-type Ca2+ channels that are important targets for many analgesic neurosteroids. Since the discovery of the role of these channels in neuronal excitability, and their presence on peripheral sensory neurons whose cell bodies are located in the DRG (Carbone and Lux, 1984), a growing interest for studying these channels in pain transmission has arisen (Todorovic et al., 2001; Bourinet et al., 2005; Jacus et al., 2012; Rose et al., 2013). Therefore, synthetic analogs of neuroactive steroids with affinity for T-channels have been synthetized to investigate their role in both acute and chronic pain models.

Among several synthetic 5α-analogs tested, our previous work has shown that ECN, [(3β,5α,17β)-17-hydroxyestrane-3-carbonitrile], a potent enantioselective blocker of T-channels without potentiating effects at GABAA receptors (Todorovic et al., 1998), induced potent analgesia when applied locally as an intraplantar injection in healthy rats (Pathirathna et al., 2005a). Furthermore, when combined with CDNC24, a GABAA selective neurosteroid without analgesic effect per se, the antinociceptive effect of ECN was greatly potentiated. This synergistic analgesia was abolished with a GABAA-receptor antagonist biccuculine, indicating that there is an interplay between GABAA receptors and T-channels in peripheral nociceptors that helps them to work in concert when alleviating acute pain (Pathirathna et al., 2005a).

These two 5α-reduced analogs have been shown to alleviate pain in chronic neuropathy as well. Our group has shown that in a model of chronic constrictive injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve, local intraplantar injections of either ECN or CDNC24 more selectively alleviated thermal nociception in neuropathic animals than in a sham group, as compared to allopregnanolone or alphaxalone (Pathirathna et al., 2005b). This can be explained by the fact that synthetic neurosteroids are more selective to either GABAA and/or T-channels, while allopregnanolone and alphaxalone have many other targets on which to exert their antinociceptive effect.

The fact that CDNC24 exerted effect in injured but not in healthy animals can be explained by the changes in expression and/or conductance of GABAA receptors during injury. The study of Xiao et al. (2002) has confirmed the increase in mRNA levels for α5 subunit of GABAA receptors on the cell bodies of peripheral sensory neurons, while Yang et al. (2004) have shown the upregulation of α5 subunit of the GABAA receptor in the spinal cord after nerve injury. It is noteworthy that both alphaxalone and allopregnanolone may exert antinociceptive effect through potentiating GABAA currents as well as inhibiting T-currents. More importantly, after blocking the GABA-ergic effect with biccuculine, a potent analgesia could still be observed, indicating that a great portion of neurosteroid-induced analgesic effect is related to the T-channel inhibition. As previously mentioned, neuroactive steroids have various targets to prevent mechanisms that trigger plasticity changes in the nervous system. Perhaps a future strategy of preventing neuropathic pain could be achieved by blocking T-channels heavily involved in neuronal excitability. Furthermore, systemic intraperitoneal administration of ECN effectively reversed mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in painful diabetic neuropathy in morbidly obese leptin-deficient ob/ob mice (Latham et al., 2009). In addition, some studies have implicated GABAA receptors in the dorsal horn of spinal cord as important targets for treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy (Jolivalt et al., 2008). These data strongly suggest that neurosteroids targeting either T-type channels and/or GABAA receptors may be beneficial in treatment of intractable pain associated with peripheral diabetic neuropathy.

Recent behavioral and immunohistological studies have confirmed the presence of both GABAA receptors and the CaV3.2 isoform of T-channels on the peripheral nociceptors (Rose et al., 2013; Obradovic et al., 2015). CaV3.2 isoform of T-channels has also been found presynaptically in the spinal cord where these channels support glutamate release from the central endings of nociceptive sensory neurons (Jacus et al., 2012). In addition, the CaV3.1 isoform of T-channels controls the opioidergic descending inhibition from the low-threshold spiking GABAergic neurons in the periaqueductal gray (PAG; Park et al., 2010). Some previous studies showed that an increase of intracellular calcium in Purkinje cells increases sensitivity to GABA (Llano et al., 1991). On the other hand, intracellular calcium decreases the affinity of GABA receptors in sensory neurons of the bullfrog (Inoue et al., 1986). Perhaps, in the PNS, blocking the T-channels leads to the decreased intracellular Ca2+, which in turn leads to the increased activity of GABAergic inhibition. Overall, these data suggest that there is a strong interaction between the GABAergic inhibitory system and T-type channels in both central and peripheral components of the pain pathway. However, exact mechanisms of this interaction remain to be determined.

Previous work from our lab has also shown that synthetic 5β-reduced neurosteroids can successfully alleviate somatic pain (Todorovic et al., 2004). The steroid structures tested both in vitro and in vivo contain either 3-cyano and 17-hydroxyl groups or 3-hydroxyl and 17-cyano groups. These selective T-channel blockers have exerted significant and dose-dependent analgesia when injected locally into the plantar surface of the hind paw in healthy rats. Specifically, (3β,5β,17β)-3-hydroxyandrostane-17-carbonitrile (3β-OH) was one of the most effective synthetic 5β- reduced neurosteroids in alleviating thermal nociception. Interestingly, the potency to block isolated T-currents in DRG neurons in vitro corresponded well to their potency to exert thermal antinociception in vivo. Furthermore, 3β-OH has been recently shown to possess hypnotic effect and was able to induce loss of righting reflex in neonatal rats without causing harmful effects to the brain of exposed animals (Atluri et al., 2018). It is reasonable to assume that both analgesic and hypnotic effects were likely exerted by blocking low voltage activated T-channels, suggesting that this novel synthetic neurosteroid with a specific and selective mechanism of action could be used for preemptive analgesia and anesthesia. However, further studies are needed to test this notion, and to investigate the effects of other synthetic neurosteroid analogs in both acute and chronic pain models.

Conclusion

Endogenous neurosteroids are very potent molecules with effects on many crucial processes in the nervous system. By targeting several different receptor systems, they are able to reduce maladaptive changes in the sensory nervous system, which in turn could prevent the development of central sensitization and chronic pain states. Perhaps, increasing the production of endogenous neurosteroids, such as progesterone and allopregnanolone, in the spinal cord and peripheral nerves would be a future therapeutic option for treating various pain states in humans. This strategy has already been employed in several animal studies and has proven successful in neuropathic, inflammatory, as well as in postoperative pain models (Aouad et al., 2009; Giatti et al., 2009; Hernstadt et al., 2009; Mitro et al., 2012; Xiong et al., 2017). By targeting specific translocator protein-18 kDa (TSPO) and/or liver X receptors (LXR), it is possible to increase neuronal steroidogenesis, thus preventing systemic endocrine effects that could appear as a consequence of systemic application of neurosteroids.

On the other hand, synthetic 5α- and 5β-reduced steroid analogs have great potential in treating acute and chronic pain. Since rigid steroid molecules can be sculpted to generate more selective compounds towards GABAA receptors and T-channels, they may be the most interesting in terms of further development as novel pain therapies. An example would be 3β-OH, a synthetic neurosteroid with hypnotic and analgesic properties, that could be a promising new agent to reduce postsurgical hyperalgesia, when applied as a part of a balanced anesthesia, thus potentially reducing the necessity for other analgesic drugs, such as opioids after surgery. By specifically targeting key ion channels that contribute to the modulation of pain perception, synthetic neurosteroids could in turn alleviate pain in patients, hopefully with less adverse events than currently used therapies. Future clinical trials are necessary to investigate their analgesic potential and safety profile in the human population.

Author Contributions

SJ wrote the main draft of the manuscript. ST, VJ-T, and DC revised the draft of the manuscript and made final corrections. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tamara Timic Stamenic for providing the drawing of the spinal cord. SJ created Figure 2.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by NIH grant 1 R01 GM123746-01 to ST and VJ-T, the funds from the Department of Anesthesiology at UC Denver.

References

- Adeosun S. O., Hou X., Jiao Y., Zheng B., Henry S., Hill R., et al. (2012). Allopregnanolone reinstates tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive neurons and motor performance in an MPTP-lesioned mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 7:e50040. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi A. M. (2003). Gonadal hormones and sex differences in pain reactivity. Clin. J. Pain 19 168–174. 10.1097/00002508-200305000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi A. M., Bonifazi M. (2006). Sex hormones, central nervous system and pain. Horm. Behav. 50 1–7. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi A. M., Ceccarelli I., Fiorenzani P., De Padova A. M., Massafra C. (2004). Testosterone affects formalin-induced responses differently in male and female rats. Neurosci. Lett. 361 262–264. 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aouad M., Charlet A., Rodeau J. L., Poisbeau P. (2009). Reduction and prevention of vincristine-induced neuropathic pain symptoms by the non-benzodiazepine anxiolytic etifoxine are mediated by 3α-reduced neurosteroids. Pain 147 54–59. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt-Nielsen L., Bajaj P., Drewes A. M. (2004). Visceral pain: gender differences in response to experimental and clinical pain. Eur. J. Pain 8 465–472. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf S., Bouhana K. S., Pheneger J., Andrews S. W., Walsh D. A. (2016). Selective inhibition of tropomyosin-receptor-kinase A (TrkA) reduces pain and joint damage in two rat models of inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 18:97. 10.1186/s13075-016-0996-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atluri N., Joksimovic S. M., Oklopcic A., Milanovic D., Klawitter J., Eggan P., et al. (2018). A neurosteroid analogue with T-type calcium channel blocking properties is an effective hypnotic, but is not harmful to neonatal rat brain. Br. J. Anaesth. 120 768–778. 10.1016/j.bja.2017.12.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoola C., Hwang S. M., Hong S. J., Rose K. E., Boyd C., Bozic N., et al. (2014). Inhibition of CaV3.2 T-type calcium channels in peripheral sensory neurons contributes to analgesic properties of epipregnanolone. Psychopharmacology 231 3503–15. 10.1007/s00213-014-3588-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basbaum A. I., Bautista D. M., Scherrer G., Julius D. (2009). Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 139 267–284. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulieu E., Robel P. (1990). Neurosteroids: a new brain function? J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37 395–403. 10.1016/0960-0760(90)90490-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulieu E. E., Robel P., Schumacher M. (1999). Contemporary Endocrinology. Neurosteroids: a New Regulatory Function in the Nervous System. Totowa: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D., Lambert J. J. (2005). Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA A receptor. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6 565–575. 10.1038/nrn1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E., Alloui A., Monteil A., Barrère C., Couette B., Poirot O., et al. (2005). Silencing of the Cav3.2 T-type calcium channel gene in sensory neurons demonstrates its major role in nociception. EMBO J. 24 315–324. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton R. D. (2013). Neurosteroids as regenerative agents in the brain: therapeutic implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 9 241–250. 10.1038/nrendo.2013.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brot M. D., Akwa Y., Purdy R. H., Koob G. F., Britton K. T. (1997). The anxiolytic-like effects of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone: interactions with GABA(A) receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 325 1–7. 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)00096-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone E., Lux H. D. (1984). A low voltage-activated, fully inactivating Ca channel in vertebrate sensory neurones. Nature 310 501–502. 10.1038/310501a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashin M. F., Moravek V. (1927). The physiological action of cholesterol. Am. J. Physiol. 82 294–298. 10.1152/ajplegacy.1927.82.2.294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli I., Fiorenzani P., Massafra C., Aloisi A. M. (2003). Long-term ovariectomy changes formalin-induced licking in female rats: the role of estrogens. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 1:24. 10.1186/1477-7827-1-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S., Liu N. J., Gintzler A. R. (2010). Formation of mu/kappa-opioid receptor heterodimer is sex-dependent and mediates female-specific opioid analgesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 20115–20119. 10.1073/pnas.1009923107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Wang J. M., Irwin R. W., Yao J., Liu L., Brinton R. D. (2011). Allopregnanolone promotes regeneration and reduces β-amyloid burden in a preclinical model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 6:e24293. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagnone N. A., Mellon S. H. (2000). Neurosteroids: biosynthesis and function of these novel neuromodulators. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 21 1–56. 10.1006/frne.1999.0188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronel M. F., Labombarda F., De Nicola A. F., González S. L. (2014). Progesterone reduces the expression of spinal cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase and prevents allodynia in a rat model of central neuropathic pain. Eur. J. Pain 18 348–359. 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronel M. F., Labombarda F., Roig P., Villar M. J., De Nicola A. F., González S. L. (2011). Progesterone prevents nerve injury-induced allodynia and spinal NMDA receptor upregulation in rats. Pain Med. 12 1249–1261. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01178.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpechot C., Robel P., Axelson M., Sjovall J., Baulieu E. E. (1981). Characterization and measurement of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in rat brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78 4704–4707. 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan M., Scholz J., Woolf C. J. (2009). Neuropathic pain: a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 32 1–32. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dableh L. J., Henry J. L. (2011). Progesterone prevents development of neuropathic pain in a rat model: timing and duration of treatment are critical. J. Pain Res. 4 91–101. 10.2147/JPR.S17009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Basoa M., Gintzler A. R. (1997). Involvement of spinal cord δ δ opiate receptors in the antinociception of gestation and its hormonal simulation. Brain Res. 757 37–42. 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)00092-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Basoa M., Gintzler A. R. (1998). Gestational and ovarian sex steroid antinociception: synergy between spinal κ κ and δ δ opioid systems. Brain Res. 794 61–67. 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00192-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Puente B., Nadal X., Portillo-Salido E., Sánchez-Arroyos R., Ovalle S., Palacios G., et al. (2009). Sigma-1 receptors regulate activity-induced spinal sensitization and neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury. Pain 145 294–303. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye C. A., Bock B. C., Kanarek R. B. (1992). Hormonal milieu affects tailflick latency in female rats and may be attenuated by access to sucrose. Physiol. Behav. 52 699–706. 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90400-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye C. A., Cuevas C. A., Kanarek R. B. (1993). Diet and estrous cycle influence pain sensitivity in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 45 255–260. 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90116-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giatti S., Pesaresi M., Cavaletti G., Bianchi R., Carozzi V., Lombardi R., et al. (2009). Neuroprotective effects of a ligand of translocator protein-18kDa (Ro5-4864) in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Neuroscience 164 520–529. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giatti S., Romano S., Pesaresi M., Cermenati G., Mitro N., Caruso D., et al. (2015). Neuroactive steroids and the peripheral nervous system: an update. Steroids 103 23–30. 10.1016/j.steroids.2015.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guennoun R., Labombarda F., Gonzalez Deniselle M. C., Liere P., De Nicola A. F., et al. (2015). Progesterone and allopregnanolone in the central nervous system: response to injury and implication for neuroprotection. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 146 48–61. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guennoun R., Meffre D., Labombarda F., Gonzalez S. L., Deniselle M. C. G., Stein D. G., et al. (2008). The membrane-associated progesterone-binding protein 25-Dx: expression, cellular localization and up-regulation after brain and spinal cord injuries. Brain Res. Rev. 57 493–505. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd M. B., Belelli D., Lambert J. J. (2007). Neurosteroid modulation of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 116 20–34. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernstadt H., Wang S., Lim G., Mao J. (2009). Spinal translocator protein (TSPO) modulates pain behavior in rats with CFA-induced monoarthritis. Brain Res. 1286 42–52. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose M., Kuroda Y., Murata E. (2016). NGF / TrkA signaling as a therapeutic target for pain, pain pract. 16 175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M., Oomura Y., Yakushiji T., Akaike N. (1986). Intracellular calcium ions decrease the affinity of the GABA receptor. Nature 324 156–158. 10.1038/324156a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin R. W., Solinsky C. M., Brinton R. D. (2014). Frontiers in therapeutic development of allopregnanolone for Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:203 10.3389/fncel.2014.00203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacus M. O., Uebele V. N., Renger J. J., Todorovic S. M. (2012). Presynaptic CaV3.2 channels regulate excitatory neurotransmission in nociceptive dorsal horn neurons. J. Neurosci. 32 9374–9382. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0068-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolivalt C. G., Lee C. A., Ramos K. M., Calcutt N. A. (2008). Allodynia and hyperalgesia in diabetic rats are mediated by GABA and depletion of spinal potassium-chloride co-transporters. Pain 140 48–57. 10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibaly C., Meyer L., Patte-Mensah C., Mensah-Nyagan A. G. (2007). Biochemical and functional evidence for the control of pain mechanisms by dehydroepiandrosterone endogenously synthesized in the spinal cord. FASEB J. 22 93–104. 10.1096/fj.07-8930com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibaly C., Patte-Mensah C., Mensah-Nyagan A. G. (2005). Molecular and neurochemical evidence for the biosynthesis of dehydroepiandrosterone in the adult rat spinal cord. J. Neurochem. 93 1220–1230. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. W., Roh D. H., Yoon S. Y., Seo H. S., Kwon Y. B., Han H. J., et al. (2008). Activation of the spinal sigma-1 receptor enhances NMDA-induced pain via PKC- and PKA-dependent phosphorylation of the NR1 subunit in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 154 1125–1134. 10.1038/bjp.2008.159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. J., Shin H. J., Won K. A., Yang K. Y., Ju J. S., Park Y. Y., et al. (2012). Progesterone produces antinociceptive and neuroprotective effects in rats with microinjected lysophosphatidic acid in the trigeminal nerve root. Mol. Pain 8:16. 10.1186/1744-8069-8-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuba T., Quinones-Jenab V. (2005). The role of female gonadal hormones in behavioral sex differences in persistent and chronic pain: clinical versus preclinical studies. Brain Res. Bull. 66 179–188. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labombarda F., Meffre D., Delespierre B., Krivokapic-Blondiaux S., Chastre A., Thomas P., et al. (2010). Membrane progesterone receptors localization in the mouse spinal cord. Neuroscience 166 94–106. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. J., Belelli D., Harney S. C., Peters J. A., Frenguelli B. G. (2001). Modulation of native and recombinant GABAA receptors by endogenous and synthetic neuroactive steroids. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 37 68–80. 10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00124-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham J. R., Pathirathna S., Jagodic M. M., Choe W. J., Levin M. E., Nelson M. T., Lee W. Y., Krishnan K., Covey D. F., Todorovic S. M., Jevtovic-Todorovic V. (2009). Selective T-type calcium channel blockade alleviates hyperalgesia in ob/ob mice. Diabetes 58 2656–2665. 10.2337/db08-1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis I., Charalampopoulos I., Alexaki V. I., Avlonitis N., Pediaditakis I., Efstathopoulos P., et al. (2011). Neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone interacts with nerve growth factor (NGF) receptors, preventing neuronal apoptosis. PLoS Biol. 9:e1001051. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonelli E., Bianchi R., Cavaletti G., Caruso D., Crippa D., Garcia-Segura L. M., et al. (2007). Progesterone and its derivatives are neuroprotective agents in experimental diabetic neuropathy: a multimodal analysis. Neuroscience 144 1293–1304. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano I., Leresche N., Marty A. (1991). Calcium entry increases the sensitivity of cerebellar Purkinje cells to applied GABA and decreases inhibitory synaptic currents. Neuron 6 565–574. 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90059-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice T., Grégoire C., Espallergues J. (2006). Neuro(active)steroids actions at the neuromodulatory sigma1(σ1) receptor: biochemical and physiological evidences, consequences in neuroprotection. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 84 581–597. 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavlyutov T. A., Duellman T., Kim H. T., Epstein M. L., Leese C., Davletov B. A., et al. (2016). Sigma-1 receptor expression in the dorsal root ganglion: reexamination using a highly specific antibody. Neuroscience 331 148–157. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcangi R. C., Garcia-Segura L. M., Mensah-Nyagan A. G. (2008). Neuroactive steroids: state of the art and new perspectives. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65 777–797. 10.1007/s00018-007-7403-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcangi R. C., Giatti S., Calabrese D., Pesaresi M., Cermenati G., Mitro N., et al. (2014). Levels and actions of progesterone and its metabolites in the nervous system during physiological and pathological conditions. Prog. Neurobiol. 113 56–69. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon S. H., Griffin L. D. (2002). Neurosteroids: biochemistry and clinical significance. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 13 35–43. 10.1016/S1043-2760(01)00503-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensah-Nyagan A. G., Do-Rego J. L., Beaujean D., Luu-The V., Pelletier G., Vaudry H. (1999). Neurosteroids: expression of steroidogenic enzymes and regulation of steroid biosynthesis in the the central nervous system. Pharmacol. Rev. 51 63—81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensah-Nyagan A. G., Kibaly C., Schaeffer V., Venard C., Meyer L., Patte-Mensah C. (2008). Endogenous steroid production in the spinal cord and potential involvement in neuropathic pain modulation. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 109 286–293. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensah-Nyagan A. G., Meyer L., Schaeffer V., Kibaly C., Patte-Mensah C. (2009). Evidence for a key role of steroids in the modulation of pain. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34(Suppl. 1), S169–S177. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer L., Patte-Mensah C., Taleb O., Mensah-Nyagan A. G. (2010). Cellular and functional evidence for a protective action of neurosteroids against vincristine chemotherapy-induced painful neuropathy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67 3017–3034. 10.1007/s00018-010-0372-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer L., Patte-Mensah C., Taleb O., Mensah-Nyagan A. G. (2011). Allopregnanolone prevents and suppresses oxaliplatin-evoked painful neuropathy: multi-parametric assessment and direct evidence. Pain 152 170–181. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalek R. M., Banerjee P. K., Korpi E. R., Quinlan J. J., Firestone L. L., Mi Z. P., et al. (1999). Attenuated sensitivity to neuroactive steroids in gamma -aminobutyrate type A receptor delta subunit knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 12905–12910. 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan M. J. (1999). The induction of pain: an integrative review. Prog. Neurobiol. 57 1–164. 10.1016/S0301-0082(98)00048-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan M. J. (2002). Descending control of pain. Prog. Neurobiol. 66 355–474. 10.1016/S0301-0082(02)00009-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitro N., Cermenati G., Giatti S., Abbiati F., Pesaresi M., Calabrese D., et al. (2012). LXR and TSPO as new therapeutic targets to increase the levels of neuroactive steroids in the central nervous system of diabetic animals. Neurochem. Int. 60 616–621. 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnet F. P., Maurice T. (2006). The sigma 1 protein as a target for the non-genomic effects of neuro(active)steroids: molecular, physiological, and behavioral aspects. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 100 93–118. 10.1254/jphs.CR0050032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradovic A. L., Scarpa J., Osuru H. P., Weaver J. L., Park J. Y., Pathirathna S., et al. (2015). Silencing the α2 subunit of γ-aminobutyric acid type a receptors in rat dorsal root ganglia reveals its major role in antinociception posttraumatic nerve injury Anesthesiology 123 654–667. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortíz-Rentería M., Juárez-Contreras R., González-Ramírez R., Islas L. D., Sierra-Ramírez F., Llorente I., et al. (2018). TRPV1 channels and the progesterone receptor Sig-1R interact to regulate pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115 E1657–E1666. 10.1073/pnas.1715972115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C., Kim J. H., Yoon B. E., Choi E. J., Lee C. J., Shin H. S. (2010). T-type channels control the opioidergic descending analgesia at the low threshold-spiking GABAergic neurons in the periaqueductal gray. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 14857–14862. 10.1073/pnas.1009532107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathirathna S., Brimelow B. C., Jagodic M. M., Krishnan K., Jiang X., Zorumski C. F., et al. (2005a). New evidence that both T-type calcium channels and GABAAchannels are responsible for the potent peripheral analgesic effects of 5α-reduced neuroactive steroids. Pain 114 429–443. 10.1016/j.pain.2005.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathirathna S., Todorovic S. M., Covey D. F., Jevtovic-Todorovic V. (2005b). 5α-reduced neuroactive steroids alleviate thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia in rats with neuropathic pain. Pain 117 326–339. 10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patte-Mensah C., Kappes V., Freund-Mercier M. J., Tsutsui K., Mensah-Nyagan A. G. (2003). Cellular distribution and bioactivity of the key steroidogenic enzyme, cytochrome P450side chain cleavage, in sensory neural pathways. J. Neurochem. 86 1233–1246. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patte-Mensah C., Kibaly C., Boudard D., Schaeffer V., Begle A., Saredi S., et al. (2006). Neurogenic pain and steroid synthesis in the spinal cord. J. Mol. Neurosci. 28 17–32. 10.1385/JMN/28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patte-Mensah C., Kibaly C., Mensah-Nyagan A. G. (2005). Substance P inhibits progesterone conversion to neuroactive metabolites in spinal sensory circuit: a potential component of nociception. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 9044–9049. 10.1073/pnas.0502968102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patte-Mensah C., Penning T. M., Mensah-Nyagan A. G. (2004). Anatomical and cellular localization of neuroactive 5 alpha/3 alpha-reduced steroid-synthesizing enzymes in the spinal cord. J. Comp. Neurol. 477 286–299. PubMed. 10.1002/cne.20251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S. M., Purdy R. H. (1992). Neuroactive steroids. FASEB J. 6 2311–2322. 10.1096/fasebj.6.6.1347506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pediaditakis I., Efstathopoulos P., Prousis K. C., Zervou M., Arévalo J. C., Alexaki V. I., et al. (2016). Selective and differential interactions of BNN27, a novel C17-spiroepoxy steroid derivative, with TrkA receptors, regulating neuronal survival and differentiation. Neuropharmacology 111 266–282. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley J. L., III, Robinson M. E., Wise E. A., Myers C. D., Fillingim R. B. (1998). Sex differences in the perception of noxious experimental stimuli: a meta-analysis. Pain 74 181–187. 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00199-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roglio I., Bianchi R., Gotti S., Scurati S., Giatti S., Pesaresi M., et al. (2008). Neuroprotective effects of dihydroprogesterone and progesterone in an experimental model of nerve crush injury. Neuroscience 155 673–685. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose K. E., Lunardi N., Boscolo A., Dong X., Erisir A., Jevtovic-Todorovic V., et al. (2013). Immunohistological demonstration of CaV3.2 T-type voltage-gated calcium channel expression in soma of dorsal root ganglion neurons and peripheral axons of rat and mouse. Neuroscience 250 263–274. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougé-Pont F., Mayo W., Marinelli M., Gingras M., Le Moal M., et al. (2002). The neurosteroid allopregnanolone increases dopamine release and dopaminergic response to morphine in the rat nucleus accumbens. Eur. J. Neurosci. 16 169–173. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02084.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M., Mattern C., Ghoumari A., Oudinet J. P., Liere P., Labombarda F., et al. (2014). Revisiting the roles of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the nervous system: resurgence of the progesterone receptors. Prog. Neurobiol. 113 6–39. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M., Hussain R., Gago N., Oudinet J. P., Mattern C., Ghoumari A. M. (2012). Progesterone synthesis in the nervous system: implications for myelination and myelin repair. Front. Neurosci. 6:10. 10.3389/fnins.2012.00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stell B. M., Brickley S. G., Tang C. Y., Farrant M., Mody I. (2003). Neuroactive steroids reduce neuronal excitability by selectively enhancing tonic inhibition mediated by delta subunit-containing GABAA receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 14439–14444. 10.1073/pnas.2435457100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic S. M., Jevtovic-Todorovic V., Meyenburg A., Mennerick S., Perez-Reyes E., Romano C., et al. (2001). Redox modulation of T-Type calcium channels in rat peripheral nociceptors. Neuron 31 75–85. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00338-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic S. M., Prakriya M., Nakashima Y. M., Nilsson K. R., Han M., Zorumski C. F., et al. (1998). Enantioselective blockade of t-type Ca2 + current in adult rat sensory neurons by a steroid that lacks gamma-aminobutyric acid-modulatory activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 54 918–927. 10.1124/mol.54.5.918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic S. M., Pathirathna S., Brimelow B. C., Jagodic M. M., Ko S. H., Jiang X., et al. (2004). 5beta-reduced neuroactive steroids are novel voltage-dependent blockers of T-type Ca2 + channels in rat sensory neurons in vitro and potent peripheral analgesics in vivo. Mol. Pharmacol. 66 1223–1235. 10.1124/mol.104.002402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Singh C., Liu L., Irwin R. W., Chen S., Chung E. J., et al. (2010). Allopregnanolone reverses neurogenic and cognitive deficits in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 6498–6503. 10.1073/pnas.1006236107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H. S., Huang Q. H., Zhang F. X., Bao L., Lu Y. J., Guo C., et al. (2002). Identification of gene expression profile of dorsal root ganglion in the rat peripheral axotomy model of neuropathic pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 8360–8365. 10.1073/pnas.122231899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong B. J., Xu Y., Jin G. L., Liu M., Yang J., Yu C. X. (2017). Analgesic effects and pharmacologic mechanisms of the Gelsemium alkaloid koumine on a rat model of postoperative pain. Sci. Rep. 7:14269. 10.1038/s41598-017-14714-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. A., Zhang F. X., Huang F., Lu Y. J., Li G. D., Bao L., et al. (2004). Peripheral nerve injury induces trans-synaptic modification of channels, receptors and signal pathways in rat dorsal spinal cord. Eur. J. Neurosci. 19 871–883. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03121.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S. Y., Roh D. H., Seo H. S., Kang S. Y., Moon J. Y., Song S., et al. (2010). An increase in spinal dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) enhances NMDA-induced pain via phosphorylation of the NR1 subunit in mice: involvement of the sigma-1 receptor. Neuropharmacology 59 460–467. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilhofer H. U., Wildner H., Yevenes G. E. (2013). Fast synaptic inhibition in spinal sensory processing and pain control. Physiol. Rev. 92 193–235. 10.1152/physrev.00043.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]