Abstract

Introduction:

At the time of selection, police personnel undergo various health and fitness tests but subsequently health assessments are not done regularly. Unhealthy lifestyle and challenging work environment predispose them to various somatic sequelae, including cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and psychological disorders, etc., There is limited epidemiological data on the morbidity profile among police personnel in India.

Aim:

To study the morbidity profile and the treatment-seeking behavior among police personnel in National Capital Region (NCR), India.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted between May and November, 2014 on 300 police personnel working in the NCR, India. We administered a predesigned, pretested questionnaire (α = 0.63) to the study participants based on World Health Organization-STEPS tool for assessing morbidity profile, lifestyle risk factors, and treatment-seeking behavior after obtaining informed consent from the study participants.

Results:

Health complaints were reported by around half (n = 149, 49.6%) of the participants with the morbidity risk of 0.71 per person. The most common complaints were related to the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal system. Only around half of the affected participants took any treatment. Hospitalization rate reflected from past 1-year hospital admissions among participants was (n = 23, 7.7%). Data analysis suggested morbidity status of police personnel to be significantly associated with lifestyle risk factors such as abdominal obesity (n = 129, 86.5%), obstructive sleep apnea (n = 54, 36.2%), and distress (n = 48, 32.2%).

Conclusion:

Busy and challenging work life and poor control of health lead to high morbidity among police personnel. Regular health checks and lifestyle promotional activities are highly recommended to maintain a healthy police force.

Keywords: Law enforcement, lifestyle, occupational health

INTRODUCTION

Physical fitness determines the performance of an individual in his/her day-to-day life. The main job of policemen is to maintain law and peace in society; therefore, fitness remains the key factor in their job. After joining the police force, they are subjected to various rigorous tests as per the norms of physical fitness. But later, their physical fitness is not assessed regularly.[1] Policing is synonymous to working in a challenging and stressful job environment. The various stressors faced by a police personnel include irregular working hours, shift work, duty tours to areas of conflict, away from home for long periods, confronting criminals and dangerous situations, always in a state of alertness even when off duty, highly hierarchical system of rank and stress of career development, etc.[2] These stressors affect police personnel's life adversely, and due to enormous work stress, police personnel suffer from different physiological as well psychosocial problems.[3]

Literature review suggests that occupational morbidity, despite being an ever-growing concern, has remain largely ignored in police services.[4] In the absence of sufficient knowledge on burden and characteristics of morbidities, personnel remain at continued health risk, which adversely affects their quality of life. Literature review suggests a high prevalence of various morbidities among policemen ranging from physical to psychological and behavioral problems. Past studies have highlighted the morbidities to a limited extent only being restricted to broad categories. Common disorders reported are musculoskeletal pain, nervousness/anxiety, sleep disturbance, substance abuse, etc.[5,6] Few studies have reported specific morbidities, e.g., anemia, visual abnormalities, and varicose veins.[7] Repeated strain to body's self-regulation as in police service has been linked to central obesity, insulin resistance, cardiovascular problems, depression, Cushing's disease, etc.[8] In addition, high rates for cancers of the colon and liver, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, homicide, etc., have been reported in police personnel.[9]

In the wake of limited socio-epidemiological data of morbidities among Indian police personnel, the present study was planned. It envisages assessing disease profile, risk factors, and treatment-seeking behavior for a detailed understanding of a range of issues deteriorating their health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted across police stations located in a randomly chosen central district of the NCR. Lists of all police zones and districts in the NCR were procured and one district was randomly chosen. Afterwards, appropriate permissions were obtained from the additional commissioner of police (district office) for conducting the study. A sample size of 300 police personnel was determined assuming morbidity prevalence of 25%. Subsequently, samples of 20 personnel, each from all the 15 police stations in the district, were included in the study. For an accurate assessment, occupational morbidity and risk inclusion criteria were set for the study after expert consultations. All personnel irrespective of age and gender with more than 5 years of service and currently working in nonclerical and nongazetted positions were included in the study. Personnel posted in traffic duty and those who did not consent or unavailable were excluded and replaced by other randomly selected personnel fulfilling inclusion criteria using the station duty roster. The study duration duty roster. The study duration was of 6 months between May and November, 2014 and informed written consents were taken from the study participants. The study was a part of an intramural project under Department of Community Medicine, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi.

Data were collected from participants by administering a self-designed, pretested, semi-structured questionnaire, consisting of questions to assess information such as identification data, morbidity profile (present and past illnesses and treatment), treatment behavior, and lifestyle risk factors, viz., substance abuse (alcohol and tobacco intake), diet (salt and fruit/vegetable intake), physical inactivity, etc., using a 42-item objective proforma based on WHO STEPwise approach questionnaire v. 2.1.17,[10] mental stress by Goldberg general health questionnaire containing 12 items,[11] and obstructive sleep apnea by Berlin questionnaire.[12] Included questionnaires have been thoroughly validated worldwide and freely available online for research purpose. Anthropometric and clinical examinations were done to assess height (cm), weight (kg), waist circumference (cm), waist/hip ratio, hip circumference (cm), body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (mm Hg), and random blood sugar levels (g/dL).

Data collection

Selected personnel were administered questionnaire according to their language preference (Hindi/English) and were asked to fill them accordingly. The proforma in either language were pretested and validated for internal consistency for the study population (Cronbach's alpha α =0.63). The introductory interview, proforma filling, and examination were conducted in a separate room to maintain privacy. Morbidity profiling of the participants was done based on present (new or existing) health condition. The participants were informed in prior to bring their present and past medical records if applicable for data verification. Post data collection and examination, participants were individually counselled regarding their health problems (if any). All available participants were provided with healthy lifestyle promotion package at respective police stations upon data collection.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered in Microsoft Office Excel 2007 and subsequently analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 17.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc. Software. Qualitative data were expressed in percentages and Chi-square test was used for comparison between proportions. Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval was used to quantify the risk factors and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Prior permissions were obtained from the police authorities and a written informed consent was taken from all the study participants. Confidentiality of data was strictly ensured at all stages of the study. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee.

RESULTS

Mean age of study participants was 41.50 ± 8.90 years, with most being male (n = 268, 89.3%). Mean years of police service among participants were 13.5 ± 2.1 years. Almost half (n = 142, 47.3%) participants were graduate and most were of constabulary rank (n = 238, 79.3%) similar to their general representation in services.

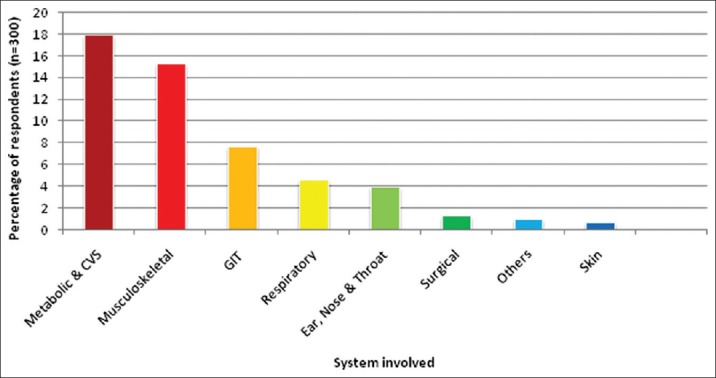

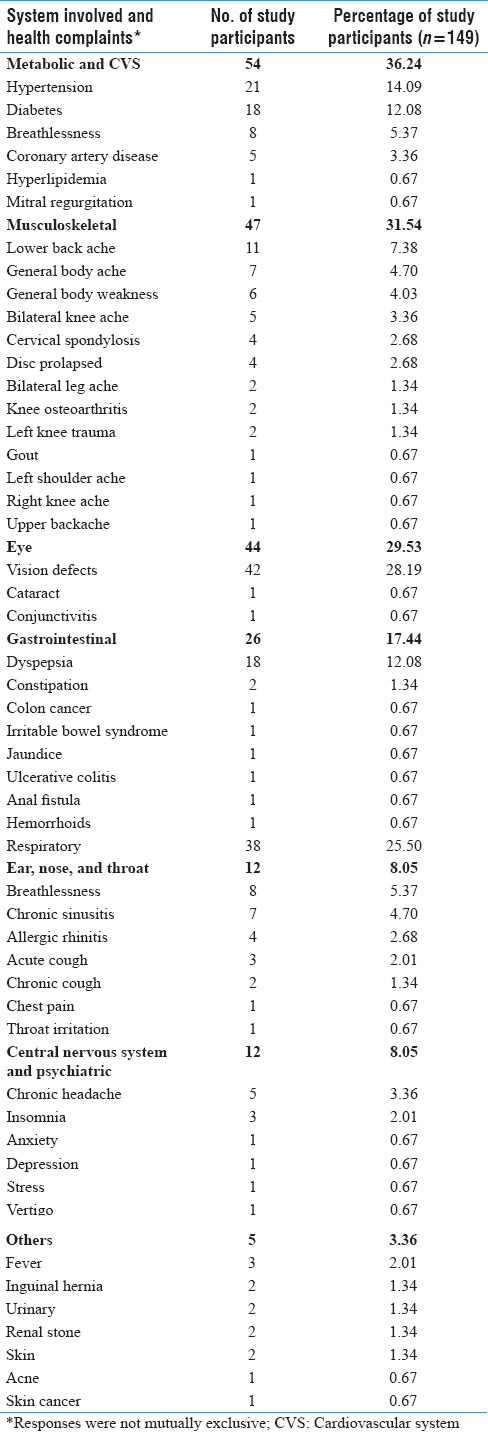

The presence of one or more presenting health complaints was reported by around half (n = 149, 49.6%) of the study participants. Among the ones with health complaints, most prevalent were related to metabolic and cardiovascular (n = 54, 36.2%), musculoskeletal (n = 47, 31.5%), vision (n = 44, 29.5%), respiratory system (n = 38, 25.5%), etc., [Figure 1] most commonly vision defects (n = 42, 28.1%), hypertension (n = 21, 14.0%), diabetes (n = 18, 12.0%), dyspepsia (n = 18, 12.0%), and lower back ache (n = 11, 7.3%) etc., were reported [Table 1, Figure 1].

Figure 1.

System wise distribution of morbidities among study participants

Table 1.

Morbidity profile among study participants (health complaint and system involved)

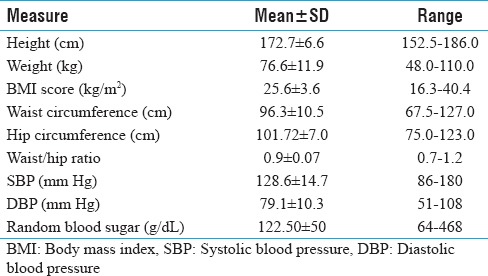

Anthropometric examination of the study participants revealed an average BMI of 25.6 kg/m2 and waist/hip ratio of 0.9 cm, respectively. Subsequently on clinical examination, mean blood pressure was 128.6/79.1 mm Hg and random blood sugar 122.5 mg/dL [Table 2].

Table 2.

Results of anthropometric and clinical examination of study participants

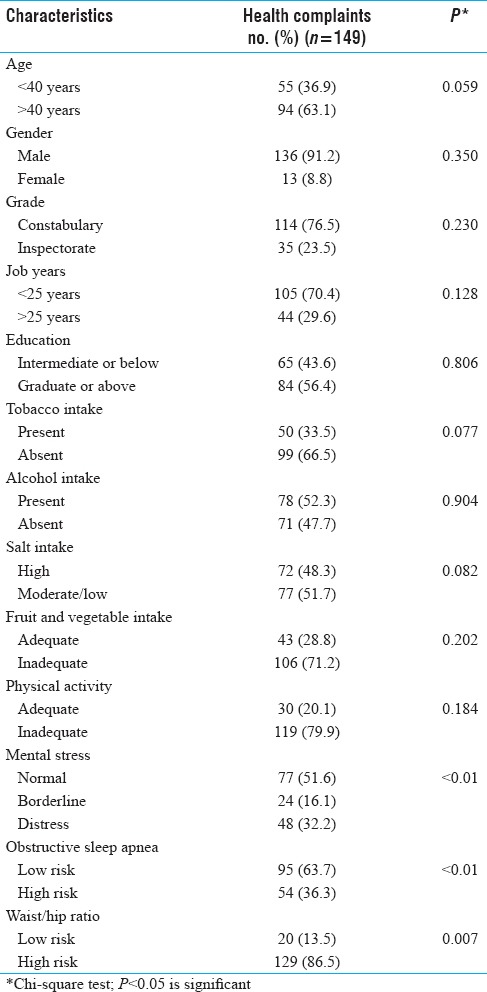

The presence of health complaint/s (morbidity status) among the study participants was significantly associated with distress (n = 48, 32.2%), obstructive sleep apnea (n = 54, 36.2%), and abdominal obesity (n = 129, 86.5%). Demographic variables such as age (>40 years), gender (male), inspector rank, job years (>25 years), and education (graduate or above) had a higher but nonsignificant association to the morbidity status. There was a high burden of lifestyle risk factors (n = 149), viz., tobacco, alcohol, high salt, inadequate fruit/vegetable intake, and physical inactivity among morbid participants, but were not found significantly linked to their morbidity profile [Table 3].

Table 3.

Distribution of presenting complaint and its determinants among study participants

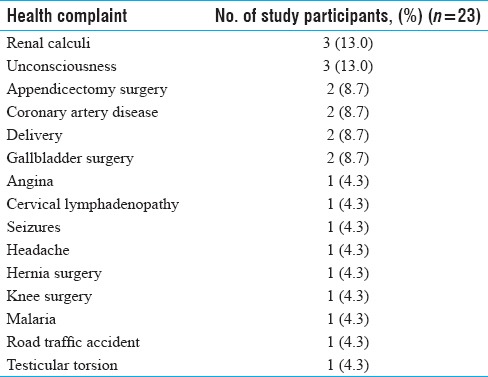

Some (n = 23, 7.7%) participants also reported history of past 1-year hospitalization. Major health complaints resulting in hospitalization were renal calculi, loss of consciousness, coronary artery disease, delivery, and surgeries such as appendicectomy, cholecystectomy, etc., [Table 4].

Table 4.

Distribution of health complaints for hospital admission (past one year) among study participants

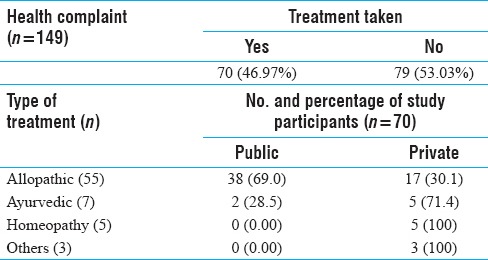

Only about half (n = 70, 46.9%) participants having health complaints took any kind of treatment. Of those, majority participants took allopathic treatment (n = 55, 78.5%) from public (govt.) health facilities (n = 38, 69.0%). Others (n = 15, 21.5%) sought alternative treatment such as Ayurveda (n = 7, 10.0%), Homeopathy (n = 5, 7.1%), and others (n = 3, 4.2%), including Unani, traditional remedies mostly from private sources (n = 13, 86.6%) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Treatment seeking behavior among study participants

DISCUSSION

The present study suggests a high burden (n = 149, 49.6%) of health complaints among police personnel amounting to morbidity risk of 0.71 per person. Similar to past evidence majority of problems were linked to metabolic and cardiovascular system (n = 54, 36.2%) resulting from mental stress (n = 48, 32.2%), obstructive sleep apnea (n = 54, 36.3%), and abdominal obesity (n = 129, 86.5%).[2,3,5,7,8] Affected participants had heavy burden of lifestyle risk factors (n = 149), viz., tobacco intake (n = 50, 33.5%), alcohol intake (n = 78, 52.3%), excess salt intake (n = 72, 48.3%), inadequate fruit/vegetables intake (n = 106, 71.2%), and physical inactivity (n = 119, 79.9%). Musculoskeletal problems were commonly (n = 46, 30.87%) reported due to overwork, sustained postures and long hours of duty which are highly characteristic of police service.[13,14]

Sustained exposures to various occupational stressors lead to poor lifestyle among personnel as reflected by heavy burden of risk factors.[15,16] Poor lifestyle leads to spectrum of diseases among personnel ranging from eye (n = 44, 29.5%) and gastrointestinal system (n = 26, 17.4%), respiratory disorders (n = 38, 25.5%) to central nervous system and psychiatric illnesses (n = 12, 8.0%).[5,6,8,9,14,17] In the present study, prevalent morbidities were vision defects (n = 42, 28.1%), hypertension (n = 21, 14.0%), diabetes (n = 18, 12.0%), dyspepsia (n = 18, 12.0%), and lower backache (n = 11, 7.3%). Johns et al. in their study on Kerala policemen reported backache (31.9%), joint pain (21.1%), hypertension (17.9%), diabetes (12.5%), and mental stress (15.1%).[5] Similarly, a study reported diabetes (37%), hypertension (33%), anemia (25%), urinary (12%), and eye complaints (10%) among Vijaywada policemen.[7] Statistical analysis of present study suggested that morbidity status of personnel was significantly associated with mental stress (P < 0.01), high-risk obstructive sleep apnea (sleep disorders) (P < 0.01), and abdominal obesity (P = 0.007). Similar relationship has been demonstrated in the past by few studies among policemen worldwide.[18,19,20]

Policing is a challenging occupation and literature review suggests a higher morbidity burden among personnel compared to general population.[21,22] In one study annual hospitalization rates among study participants were significantly higher (n = 23, 7.6%) compared to general population (0.06%), and most commonly due to renal colic and loss of consciousness.[23]

Treatment-seeking behavior among personnel was poor as only less than half (n = 70, 46.9%) of affected ones took any kind of treatment for their illness. Multiple factors have been attributed to poor health behaviors among armed personnel such as poor awareness, attitude, and referral support along with dependence on informal channels for seeking care such as work encounters, peer advice, self-medication, etc.[24] For treatment majority preferred allopathy (n = 55, 78.5%) through public health institutions (n = 38, 54.2%). Almost one of four (n = 15, 21.5%) participants took alternative treatments, viz., Ayurveda, Unani, Homeopathy, etc., This behavioral pattern corresponds to previously reported use of outpatient facilities, and public providers, an effect that is particularly strong at lower income level.[25] Profiling of morbidity and treatment behavior is pertinent keeping in mind heavy burden of occupational and lifestyle risk factors and morbidities among police personnel. Such exercise envisages averting heavy socioeconomic and psychological impact on the police personnel in the future through appropriate health promotion strategies. Present study suggests widespread lacunae in preventive, promotive, and curative services offered to the police personnel, thereby having detrimental impact on their health.

Limitations of the study

Present study relies on self-reported illness or health condition for morbidity assessment, which is amenable to information bias (recall and response). Also, no clinical assessment and laboratory tests were conducted and only medical records were used for ascertaining morbidity status and history. Absence of a control group limits the generalization and extrapolation of the study results.

CONCLUSION

The present study reflects poor health status among police personnel as almost half of them were found with presenting health complaints. A uniform distribution of morbidities across different subject groups based on age, gender rank, and education was observed. Poor treatment-seeking behavior was reflected as almost half of the police personnel were not taking any treatment for their illness. Police personnel were found to have a high burden of various lifestyle risk factors and morbidity risk due to challenging work environment. The authors suggest that police departments must regularly conduct health reviews, checkups, and promotional activities for ensuring a healthy and efficient police workforce.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mundewadi AW, Thakare GV, Gorane SS, Agarwal PV. Resting B.P. and cold pressor test in policemen in Dhule city. Int J Basic Med Sci. 2011;2:80–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanam RN, Basuki B, Nainggolan G. Qualitative work overload and other risk factors related to hypertension risk among Indonesian Police Mobile Brigade (Brimob) Med J Indonesia. 2008;17:188–96. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franke WD, Cox DF, Schultz DP, Anderson DF. Coronary heart disease risk factors in employees of Iowa's Department of Public Safety compared to a cohort of the general population. Am J Ind Med. 1997;31:733–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199706)31:6<733::aid-ajim10>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Randall C. Managing occupational stress injury in police services: A literature review. Int Pub Health J. 2013;5:413. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johns F, Kumar A, Alexander AV. Occupational hazards vs morbidity profile among police force in Kerala. Kerala Med J. 2012;5:63–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saha A, Sahu S, Paul G. Evaluation of cardio-vascular risk factor in police officers. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2010;1:263–71. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jahnavi G, Patra SR, Chandrasekhar CH, Rao BN. Unmasking the health problems faced by the police personnel. Glob J Med Pub Health. 2012;1:64–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Violanti JM. Shifts, extended work hours, and fatigue: An assessment of health and personal risks for police officers. US Department of Justice. 2012:45–8. No. NIJ 234964. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guralnick L. Occupations of men dying from accidents in the United States, 1950. Pub Health Rep. 1961;76:817–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. The WHO STEPwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance (STEPS) Instrument v-2.1 (Core and Expanded) 2012. [Last accessed on 2017 April 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/STEPS_Instrument_v2.1.pdf .

- 11.Goldberg DP, Williams P. A user's guide to the GHQ. Windsor, UK: NFER-Nelson; 1988. p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, Chung SA, Vairavanathan S, Islam S, et al. Validation of the Berlin questionnaire and American Society of Anesthesiologists checklist as screening tools for obstructive sleep apnea in surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:822–30. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816d91b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho TS, Jeon WJ, Lee JG, Seok JM, Cho JH. Factors affecting the musculoskeletal symptoms of Korean police officers. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26:925–30. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almale BD, Bansode-Gokhe SS, Suryawanshi SR, Vankudre AJ, Pawar VK, Patil RB. Health profile of Mumbai police personnel: A cross sectional study. Indian J Forensic Community Med. 2015;2:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh S, Kar SK. Sources of occupational stress in the police personnel of North India: An exploratory study. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2015;19:56. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.157012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganesh KS, Naresh AG, Bammigatti C. Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension among male police personnel in urban Puducherry, India. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2015;12:242–6. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v12i4.13728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prajapati P, Modi K, Rahul K, Shah A. A study related to effects of job experience on health of traffic police personnel of Ahmedabad City, Gujarat, India. Int J Interdiscip Multidiscip Stud. 2015;2:127–33. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmerman FH. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in law enforcement personnel: A comprehensive review. Cardiol Rev. 2012;20:159–66. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318248d631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charles LE, Slaven JE, Mnatsakanova A, Ma C, Violanti JM, Fekedulegn D, et al. Association of perceived stress with sleep duration and sleep quality in police officers. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2011;13:229–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garbarino S, Magnavita N. Work stress and metabolic syndrome in police officers. A prospective study. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fekedulegn D, Burchfiel CM, Charles LE, Hartley TA, Andrew ME, Violanti JM. Shift work and sleep quality among urban police officers: The BCOPS study. J Occup Env Med. 2016;58:e66–71. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tharkar S, Kumpatla S, Muthukumaran P, Viswanathan V. High prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk among police personnel compared to general population in India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:845–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dilip TR. Understanding levels of morbidity and hospitalization in Kerala, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:746–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iversen AC, van Staden L, Hughes JH, Browne T, Greenberg N, Hotopf M, et al. Help-seeking and receipt of treatment among UK service personnel. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:149–55. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jowett M, Deolalikar A, Martinsson P. Health insurance and treatment seeking behaviour: Evidence from a low-income country. Health Econ. 2004;13:845–57. doi: 10.1002/hec.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]