Abstract

Background

Guidelines from 2005 for treating suspected sepsis in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) recommended hospitalisation and prophylactic intramuscular (IM) or intravenous (IV) ampicillin and gentamicin. In 2015, recommendations when referral to hospital is not possible suggest the administration of IM gentamicin and oral amoxicillin. In an era of increasing antimicrobial resistance, an updated review of the appropriate empirical therapy for treating sepsis (taking into account susceptibility patterns, cost and risk of adverse events) in neonates and children is necessary.

Methods

Systematic literature review and international guidelines were used to identify published evidence regarding the treatment of (suspected) sepsis.

Results

Five adequately designed and powered studies comparing antibiotic treatments in a low-risk community in neonates and young infants in LMIC were identified. These addressed potential simplifications of the current WHO treatment of reference, for infants for whom admission to inpatient care was not possible. Research is lacking regarding the treatment of suspected sepsis in neonates and children with hospital-acquired sepsis, despite rising antimicrobial resistance rates worldwide.

Conclusions

Current WHO guidelines supporting the use of gentamicin and penicillin for hospital-based patients or gentamicin (IM) and amoxicillin (oral) when referral to a hospital is not possible are in accordance with currently available evidence and other international guidelines, and there is no strong evidence to change this. The benefit of a cephalosporin alone or in combination as a second-line therapy in regions with known high rates of non-susceptibility is not well established. Further research into hospital-acquired sepsis in neonates and children is required.

Keywords: Sepsis, antibiotics, antimicrobial resistance, treatment guidelines

Introduction

Sepsis remains a leading cause of mortality and morbidity, especially during the first five days of life and in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) [1]. In 2015, of the 5.9 million deaths of children under the age of 5 years, 45% were of neonates, and this figure exceeded 50% in several regions [2]. Neonatal sepsis is the third most common cause of death in this age group with an estimated 0.4 million deaths in 2015, the vast majority of which were in LMIC [3]. Beyond the neonatal period, the first year of life carries the highest risk of death from sepsis.

In high-income countries (HIC), early-onset neonatal sepsis (EONS) is defined by occurring in the first 72 h after birth, as opposed to late-onset neonatal sepsis (LONS, onset ≥ 72 h after birth). In LMIC, many neonates are born outside health care facilities, and might become infected with community-acquired pathogens even after 72 h of life. As a result, neonatal sepsis in LMIC is often classified as community- and hospital-acquired instead of early- and late-onset [4].

WHO provides guidelines for the management of common childhood illnesses, through the Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children published for the first time in 2005 [5]. The second edition was published in 2013 [6]. It is one of a series of documents and tools supporting the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI). These guidelines focus on management of the major causes of childhood mortality in countries with limited health care (and other) resources. Recommendations for preventing neonatal infection and for the management of possible serious bacterial infection remain the same in the second edition. It recommends providing prophylactic intramuscular (IM) or intravenous (IV) ampicillin and gentamicin in neonates with documented risk factors for infection for at least 2 days and then to reassess. Treatment should be continued only if there are signs of sepsis (or positive blood culture). It recommends hospitalisation and IM or IV antibiotic therapy with a combination of gentamicin and benzylpenicillin or ampicillin for at least 7–10 days in infants aged <2 months who fulfil the case definition of serious bacterial infection. If infants are deemed to be at risk of staphylococcal infection, IV cloxacillin and gentamicin are recommended.

In many LMIC, these parenteral treatments might only be available where inpatient neonatal and paediatric care can be provided, and access to these treatments is limited by transportation, financial and/or cultural factors. In previous studies, even when these constraints were addressed, a substantial proportion of families still refused referral to hospital for young infants with possible serious bacterial infection (PSBI). A body of research undertaken in the past decade led to the development and publication in 2015 of the first guideline for Managing Possible Serious Bacterial Infection in Young Infants When Referral is not Possible [7] in infants aged <59 days. The guideline recommends (Table 1):

Option 1: IM gentamicin 5–7.5 mg/kg (for low-birthweight infants gentamicin 3–4 mg/kg) once daily for 7 days and twice daily oral amoxicillin, 50 mg/kg per dose for 7 days.

Option 2: IM gentamicin 5–7.5 mg/kg (for low-birthweight infants gentamicin 3–4 mg/kg) once daily for 2 days and twice daily oral amoxicillin, 50 mg/kg per dose for 7 days.

Table 1. Current WHO recommendation for antibiotic therapy in infants aged 0–59 days with signs of possible serious bacterial infection or for prophylaxis.

| Reference | Conditions | Antibiotics | Dosing regimen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children, 2013 | Prophylaxis in neonates with documented risk factors | IM or IV ampicillin and gentamicin for at least 2 days |

|

| Case definition PSBI | IM or IV gentamicin and benzylpenicillin or ampicillin for at least 7–10 days | ||

| Greater risk of staphylococcus infection | IV cloxacillin and gentamicin for at least 7–10 days | ||

| Managing possible serious bacterial infection in young infants when referral is not possible, 2015 | Referral to hospital for young infants with PSBI is not possible | Option 1: IM gentamicin once daily for 7 days and oral amoxicillin twice daily for 7 days |

|

| Option 2: IM gentamicin once daily for 2 days and oral amoxicillin twice daily for 7 days |

Thus, penicillin/gentamicin is recommended for community neonatal sepsis, hospital neonatal sepsis and all sepsis in children. It is known, however, that in many countries, agents with a broader spectrum such as third-generation cephalosporins (e.g. ceftriaxone) are commonly used to treat neonatal and infant sepsis [8]. Against this background, concerns are increasing regarding bacterial pathogens with reduced susceptibility to empirical medication with variations both between and within LMIC [9].

The potential need to revise the existing WHO guidelines based on new antimicrobial resistance (AMR) data or evidence relating to drug safety in neonates and children must be evaluated. This review collates evidence to support current empirical antibiotic recommendations for suspected or confirmed sepsis in neonates and children according to the most recent (≥year 2012) relevant studies.

Methods

An iterative systematic literature search was undertaken to identify published clinical evidence relevant to the review question. Searches were conducted in MEDLINE and Embase. Databases were searched using relevant medical subject headings, free-text terms and study-type filters, where appropriate. Search terms included variations of ‘anti-bacterial agents’, ‘antibiotic’, ‘sepsis’ and ‘bacteraemia’. Limits were set for the appropriate population, i.e. ‘all child (0 to 18 years)’. Studies published in languages other than English were not reviewed. The search was undertaken for manuscripts published from 2012 to cover the most recent WHO guidelines (WHO Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children, 2013).

Potentially relevant studies were identified from the search results by reviewing titles and abstracts. Full papers were then obtained and reviewed against pre-specified inclusion (antimicrobial choice, comparisons between different antibiotics and/or antibiotic classes and/or comparisons with placebo, drug therapeutic use, drug efficacy, drug safety and harm, drug resistance) and exclusion criteria (only bacterial sepsis was considered, case reports were not considered) to identify studies that addressed the review question. Fungal and viral sepsis were not taken into account in this review, although invasive candidiasis is an important emerging cause of LONS.

The Cochrane Database for Systematic Reviews was also searched using the terms ‘sepsis’ AND ‘antibiotic’.

Five international guidelines were reviewed: the Surviving Sepsis Campaign endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) [10], the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [11,12], the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) [13–15], the British Medical Journal (BMJ) Clinical Evidence [16] and the British National Formulary for Children (BNFc) [17].

Results

Evidence for current WHO recommendations: penicillin and gentamicin in community-based neonatal sepsis

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) undertaken in three low-income communities in Pakistan evaluated the failure rates of three clinic-based antibiotic regimens in young infants with clinical signs of PSBI (≤59 days old, n = 434) whose families refused hospital referral [18]. Infants were randomly allocated to receive: (i) procaine penicillin and gentamicin, reference arm, (ii) ceftriaxone or (iii) oral trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and gentamicin for 7 days. Results showed that the efficacy of a procaine benzylpenicillin–gentamicin combination was much higher than that of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole–gentamicin [treatment failure was significantly higher with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole–gentamicin compared with penicillin–gentamicin (relative risk 2.03, 95% confidence interval 1.09–3.79)]. Differences were not significant in the ceftriaxone versus penicillin–gentamicin comparison (relative risk 1.69, 95% CI 0.89 to 3.23).

The two SATTs (Simplified Antibiotic Therapy Trial) were large RCTs, one of which was conducted in five centres in Bangladesh (four urban hospitals and one urban field) [19] and the other in five centres in Pakistan [20]. It included young infants (≤59 days old, n = 2367 and ≤ 59 days old, n = 2251 per protocol, respectively) for whom referral to hospital was not possible. The trial compared the standard treatment of injectable procaine benzylpenicillin–gentamicin for 7 days (group A) with two alternative regimens: (i) injectable gentamicin and oral amoxicillin for 7 days (group B), and (ii) intramuscular procaine benzylpenicillin and gentamicin for 2 days, then oral amoxicillin for 5 days (group C). The results suggested that the two alternative regimens were as efficacious as the standard regimen when hospital admission was refused. In the SATT trial in Bangladesh, treatment failed in 78 (10%) infants in group A compared with 65 (8%) infants in group B and 64 (8%) in group C. The risk difference between groups B and A was −1.5% (95% CI −4.3 to 1.3) and between groups C and A was −1.7% (95% CI −4.5 to 1.1). Non-fatal severe adverse events were rare. Three infants in group A, two in group B and three in group C had severe diarrhoea [19]. In the SATT trial in Pakistan, treatment failed within 7 days of enrolment in 90 (12%) of infants in group A compared with 76 (10%) infants in group B and 99 (13%) in group C. The risk difference between groups B and A was −1.9% (95% CI −5.1 to 1.3) and between groups C and A was −1.7% (−2.3 to 4.5) [20].

One of two large RCTs from the AFRINEST (AFRIcan NEonatal Sepsis Trial) Group compared oral amoxicillin with injectable procaine benzylpenicillin plus gentamicin in five African centres in young infants (≤59 days old, n = 2333) with fast breathing as a single sign of PSBI illness when referral was not possible. In the procaine benzylpenicillin–gentamicin group, 234 infants (22%) failed treatment compared with 221 (19%) infants in the oral amoxicillin group (risk difference 2.6%, 95% CI −6.0 to 0.8). The results were taken to indicate that young infants with fast breathing alone can be effectively treated with oral amoxicillin as outpatients when referral to hospital is not possible [21].

The second large RCT from the AFRINEST Group, undertaken in the same countries, compared the current reference treatment for PSBI of injectable procaine benzylpenicillin–gentamicin for 7 days (group A) with a simplified regimen in young infants (≤59 days old, n = 3564) when referral was not possible. The following simplified regimens were investigated: (i) injectable gentamicin and oral amoxicillin for 7 days (group B), (ii) injectable procaine benzylpenicillin–gentamicin for 2 days, then oral amoxicillin for 5 days (group C), (iii) or injectable gentamicin for 2 days and oral amoxicillin for 7 days (group D) [22]. Treatment failed in 67 (8%) infants in group A compared with 51 (6%) in group B (risk difference −1.9%, 95% CI −4.4 to 0.1), 65 (8%) in group C (risk difference −0.6%, 95% CI −3.1 to 2.0) and 46 (5%) in group D (risk difference −2.7%, 95% CI −5.1 to 0.3). The results suggest that the three simplified regimens were as effective as injectable procaine benzylpenicillin–gentamicin for 7 days on an outpatient basis in young infants with clinical signs of severe infection, without signs of critical illness, and whose caregivers could not accept referral for hospital admission.

In these five aforementioned studies [18–22], the equivalence margin was predefined at 5%. Based on in vitro data from LMIC on a benzylpenicillin and gentamicin regimen (~4000 blood culture isolates) [23], a significant proportion of bacteraemia is not covered: 43% in neonates and 37% in infants of 1–12 months. However, this was not confirmed by the SATT trial in Pakistan which, of the five aforementioned studies, is the only one which obtained blood cultures in the majority of patients (84%) [20]. Thirty-two (86%) of 37 pathogens tested for antimicrobial susceptibility were sensitive to amoxicillin and gentamicin [20]. Interestingly, of the 2067 blood cultures obtained, only 81 (4%) were positive for a micro-organism. Overall, mortality was low in the SATT and AFRINEST studies: it was 2% in each group comparing the reference treatment of injectable procaine benzylpenicillin–gentamicin for 7 days with two alternative regimens [19], <1% in each group comparing amoxicillin with benzylpenicillin–gentamicin [20,21] and ≤2% in each group comparing the reference treatment of injectable procaine benzylpenicillin–gentamicin for 7 days with the three simplified dosing regimens [22].

Drug management in hospital-based neonatal sepsis

Two other studies in the Asian region were found. One, a retrospective study in hospitalised neonates and children (≤59 months of age, n = 183) in Bangladesh, investigated injected ampicillin and gentamicin as a first-line combination for the management of sepsis [24]. Another single-centre prospective study in India of hospitalised neonates (≤59 months old, n = 90) compared two empirical regimens: a cloxacillin and amikacin combination (n = 40) versus a cefotaxime and gentamicin combination (n = 50) for at least 10 days in cases of late-onset sepsis [25]. The study analyses of these reports are unclear and either they do not address the stated primary outcome (mortality between the two groups) or specify the statistical methods used for analyses, or do not provide numerical values for non-significant results [24,25].

All other studies retrieved since 2012 which compared the impact of different antibiotic regimens and/or routes of administration on outcome were undertaken in hospitalised patients in HIC, mainly in North America. Because of the considerable differences in pathogen spectrum, resistance patterns, but also levels and types of underlying diseases, it is unlikely that the results of these studies are directly generalisable to LMIC [26,27].

Third-generation cephalosporin monotherapy versus in combination with another antibiotic

Historically, combination therapy has been used to increase coverage and because of its potential additive clinical effect. While studies tend to show that there is no difference in clinical outcomes or mortality between mono- and combined therapy, increased toxicities with combination therapy has been documented [28,29].

Four studies since 2012 were found which compared β-lactam monotherapy with β-lactam combined with aminoglycoside in hospitalised paediatric patients in the USA [27,29–31].

In the retrospective studies by Berkowitz et al. [30] (n = 203) and Tama [29] (n = 879), there was no difference in 30-day mortality between the β-lactam monotherapy and the combination therapy of aminoglycoside and β-lactams for Gram-negative bacteria in children. Combination therapy consisting of a β-lactam agent and an aminoglycoside was not superior to monotherapy with a β-lactam agent alone for managing enterobacteriaceae bacteraemia in children. But patients receiving combination therapy had approximately twice the risk of nephrotoxicity compared with those receiving monotherapy (odds ratio 2.15, 95% CI 2.09 to 2.21) [29].

In a study of neonates and young infants (≤59 days old, n = 265), based on in vitro susceptibilities from isolates, third-generation cephalosporins combined with ampicillin would have been effective for 98.5% of infants but unnecessarily broad with a third-generation cephalosporin use for 83.8% of infants with suspected serious bacterial infection [27]. Because of the 20 Enterococcus faecalis isolates (7.5% of identified pathogens), intrinsically resistant to cephalosporins, third-generation cephalosporin monotherapy was less effective than either combination (p < 0.001).

In a retrospective study in which children receiving empirical combination therapy were matched 1:1 with children receiving empirical monotherapy [31], the 10-day mortality was similar in children (aged > 2 months to 14 years, n = 452) receiving empirical combination therapy versus empirical monotherapy (odds ratio 0.84, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.71). A survival benefit was observed when empirical combination therapy was prescribed for children growing multidrug-resistant Gram-negative organisms (n = 46) in the bloodstream (odds ratio 0.70, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.84).

A systematic review in 2013 assessed β-lactam monotherapy versus β-lactam-aminoglycoside combination therapy in patients with sepsis. It included 69 randomised and quasi-randomised trials but only four included children. In trials comparing the same β-lactam, there was no difference between study groups with regard to all-cause mortality (Relative Risk RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.30) and clinical failure (Relative Risk (RR) 1.11, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.29). In studies comparing different β-lactams, a trend for benefit with monotherapy for all-cause mortality (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.01) and a significant advantage for clinical failure (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.84) was observed, but the studies included were generally classified as being of low quality. No significant disparities emerged from analyses of participants with Gram-negative infection. Nephrotoxicity was significantly less frequent with monotherapy (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.39) [28].

Evidence for alternative antibiotic treatment options

One RCT conducted in India compared amikacin monotherapy with piperacillin/tazobactam monotherapy as empirical treatment for suspected EONS (n = 187) [32]. In this neonatal unit, amikacin or piperacillin–tazobactam was the standard regimen since reported resistance rates previously ranged between 86% and 89% for ampicillin, gentamicin and cefotaxime. Treatment failure defined as a blood culture isolate resistant to the allocated antibiotic or as a change of antibiotic was very low (n = 3 and n = 2, respectively, p = 0.44). No increased risk or significant difference between the two study groups in the incidence of secondary infection within 7 days of stopping the study antibiotic was observed, nor any difference in the incidence of fungal sepsis, nor a difference in all-cause mortality at days 7 and 28. However, only five blood cultures were positive.

A retrospective single-centre study in neonates (5–37 days old, n = 10) with persistent CoNS bacteraemia (LONS) investigated the addition of rifampicin to vancomycin for infection resolution [33]. Bacteraemia persisted for a median of 9 days (range 6–19) until the initiation of rifampicin. In all cases, the bacteraemia resolved with vancomycin–rifampicin without serious side effects and in all patients the blood cultures became negative on vancomycin–rifampicin taken 24–72 h after the initiation of rifampicin. No serious side effects were observed.

Synopsis of international guidelines

Table 2 summarises recommendations by international organisations. When selecting empirical treatment regimens, most guidelines suggest relying on data on antibiotic resistance patterns in locally prevalent pathogens at the institutional level but do not define how this should be done. They recommend individualising empirical antibiotic recommendations according to local antibiotic protocols and local pathogen susceptibility. There is little if any detail on how such data are to be used to select treatment regimens. For EONS, most guidelines are in line with WHO recommendations: NICE, AAP, BMJ and BNFc recommend the use of benzylpenicillin or ampicillin combined with gentamicin as empirical treatment and list third-generation cephalosporins as an alternative. Of note, guidelines often state that the aim is to target the most common pathogens in EONS, i.e. group B streptococcus (GBS) and Escherichia coli in HIC. More variability is seen in the suggested empirical treatment for LONS.

Table 2. Current international guidelines for the empirical treatment of suspected sepsis or blood infection.

| Guideline | Last update | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Surviving Sepsis Campaign(endorsed by IDSA) | 2012 |

|

| NICE | 2016 |

|

| AAP | 2012, 2015 |

|

| Notes: | ||

| ||

| BMJ Clinical Evidence | 2016 | Treatment should be initiated with broad-spectrum antibiotic cover appropriate for the prevalent organisms for each age group and geographical area. This should be changed to an appropriate narrow-spectrum antibiotic regimen once a causative pathogen is identified |

| ||

| Note: To cover group GBS and Gram-negative bacilli | ||

| ||

| BNFc | 2015/16 |

|

Note: IDSA – Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Dosing consideration

International guidelines differ on dosing regimens for gentamicin, from 4 to 5 mg/kg every 24–36 h. Current WHO guidelines recommend a once-daily dosing regimen, from 3 to 7.5 mg/kg/day according to age and birthweight.

Gentamicin has a narrow therapeutic index. Efficacy of aminoglycosides has been associated with high peak concentrations relative to minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the infecting micro-organism with a ratio peak concentration/MIC of >8–10, whereas low trough concentrations appear to be associated with reduced risk of nephro- and ototoxicity (at least <2 mg/L, but <1 mg/L is also often advocated) [34,35].

Although the incidence of ototoxicity detected following aminoglycoside exposure remains low (1–3%) and less than that reported in adults, gentamicin appears to be the least cochleotoxic. The specific association between hearing loss and aminoglycoside exposure is complicated, mainly owing to the presence of many other confounding factors in this population, e.g. low gestational age and birthweight, intrauterine and postnatal infections, neonatal asphyxia, requirement for prolonged oxygen therapy and respiratory support, congenital malformations, family history of hearing impairment, genetic abnormalities [36]. An association with high peak concentration has been suggested in the past but recent studies are not so categorical [35,36].

A recent systematic review considered the risk of gentamicin toxicity in neonates treated for PBSI in LMIC with the WHO recommended first-line antibiotics (gentamicin with penicillin) [37]:

-

•

Six trials reported formal assessments of ototoxicity outcomes in neonates treated with gentamicin, and the pooled estimate for hearing loss was 3% (95% CI 0 to 7%).

-

•

Nephrotoxicity was assessed in 10 studies but could not be evaluated owing to variation in the case definitions used.

-

•

Estimates of the number of neonates potentially affected by gentamicin toxicity were not undertaken owing to insufficient data.

The authors concluded that data were insufficient to assess the potential for harm in terms of toxicity associated with gentamicin treatment.

The volume of distribution of gentamicin is larger in preterm neonates as a consequence of a higher percentage of body water compared with term neonates. Kidney function is reduced in preterm neonates owing to incomplete nephrogenesis. As a consequence, recent trends are in favour of higher doses (>4 mg/kg up to 5 mg/kg) with extended dose intervals in preterm neonates (>24 h up to 48 h for the most preterm infants or more according to some authors) [38–42] to achieve higher peak concentrations for improved efficacy while maintaining low trough concentrations for safety. According to currently available knowledge, term infants should receive about 4.0–4.5 mg/kg every 24 h [43–45].

However, rates of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative (MRD GN) infections are increasing worldwide, particularly in LMIC. As a result, many enterobacteraciae gentamicin MIC are 4 or higher nowadays, compared with 0.5 or 1 in the past when dosing recommendations were developed, and so determining the appropriate dosing recommendations has become very challenging. It might be possible that even higher doses are required to reach effective exposure (10× MIC) with longer extended dosing interval periods (to prevent toxicity). Such questioning emphasises the urgent need for further prospective studies in populations with MRD GN specifically collecting PBSI isolates (there are few isolates to date) with MICs to gentamicin, actual dosing and peak concentration/trough estimation, and both clinical outcomes (infection resolution, toxicity).

Using the 24-h dosing interval for all neonates suggested by WHO may expose a large proportion of patients to the risk of toxicity, especially when treatment is prolonged (>48 h), because of the possibility of drug accumulation. However, providing various dosing intervals that stratify neonates may complicate feasibility and acceptability.

Pharmacokinetics data for neonates are scarce and so it is difficult to summarise current dosing regimens of β-lactams in this review. Antibacterial activity of β-lactams is best characterised by time-dependent killing. The pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameter that correlates with the clinical and bacteriological efficacy of β-lactam antibiotics is the percentage of time that the serum free drug concentration exceeds the MIC for the pathogen (time above the MIC). Overall, β-lactams present a favourable safety profile and most dosing recommendation suggested by WHO are in line with current knowledge [45].

Review of harm and toxicity – safety

Safety and harm toxicity data for empirical antibiotic treatment used in PSBI are summarised in Table 3 [37,46–55].

Table 3. Safety data summary for empirical antibiotic treatment used in possible serious bacterial infection.

| Antibiotic | Adverse events and contraindications | Relevant interactions |

|---|---|---|

|

Serious toxicity is rare in association with penicillin therapy | Concomitant use of bacteriostatic antibacterial agents (i.e. tetracyclines, sulfonamides, erythromycins, chloramphenicol) should be avoided |

| Caution should also be exerted with the use of certain other β-lactam antibiotics, namely cephalosporins (especially 1st- and 2nd-generation, e.g. cefalexin, cefaclor) and carbapenems (e.g. meropenem) as cross-reactivity in the allergies between these classes can occur (but its importance has frequently been overstated) | ||

| ||

| 3rd-generation cephalosporin: Cefotaxime |

|

Concurrent use of cephalosporin with: |

| ||

| 3rd-generation cephalosporin: Ceftriaxone |

|

Concurrent use of cephalosporin with: |

| ||

| Broadspectrum antibiotics and prolonged duration of antibiotic therapy |

|

|

Pathogen distribution and antimicrobial resistance patterns

Pathogen distribution

In HIC, the most common causes of EONS are GBS and E. coli. The remaining cases of EONS are caused by Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), Listeria monocytogenes and other Gram-negative bacteria [4]. In LONS (mainly in very low-birthweight infants), the main pathogens are CoNS, responsible for half of the episodes. Other important aetiological agents are E. coli, klebsiella spp. and candida spp. Less common causes of LONS include S. aureus, enterococcus spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [4,56].

Aetiological data from LMIC, particularly from rural, community-based studies, are very limited. In systematic reviews on this topic, the commonest causes of neonatal bacteraemia in LMIC are S. aureus, E. coli and klebsiella spp. and, in older infants, S. aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, klebsiella spp. and E. coli, and non-typhoidal salmonella [23,57]. Although there are some similarities between community- and hospital-acquired sepsis, available data are of insufficient quality to justify firm conclusions [4]. Acinetobacter spp., for example, appear to be predominant in some regions [58,59], while the incidence is very low in other regions. GBS is responsible for only 2–8% of cases in LMIC. It is possible that infants with GBS infection are underreported, since this pathogen usually presents very early in life and infected newborns might die or be adequately treated before blood cultures or other relevant microbiological samples are obtained. CoNS is responsible for a lower proportion of hospital-acquired infections than in HIC [4], and this may be related to the use of invasive medical devices, e.g. central venous catheters. Interestingly, in the SATT in Pakistan which obtained blood cultures from 2067 (84%) infants, a high frequency of campylobacter was found in the absence of diarrhoea (22% of the positive blood cultures) [20].

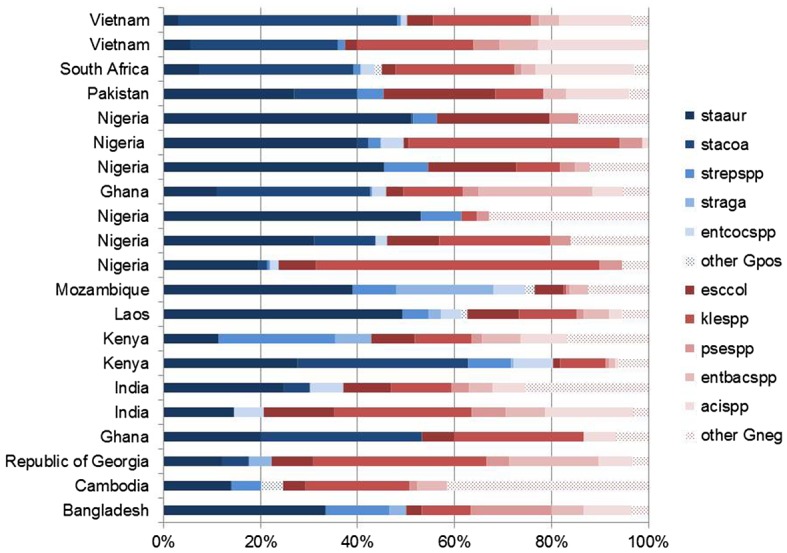

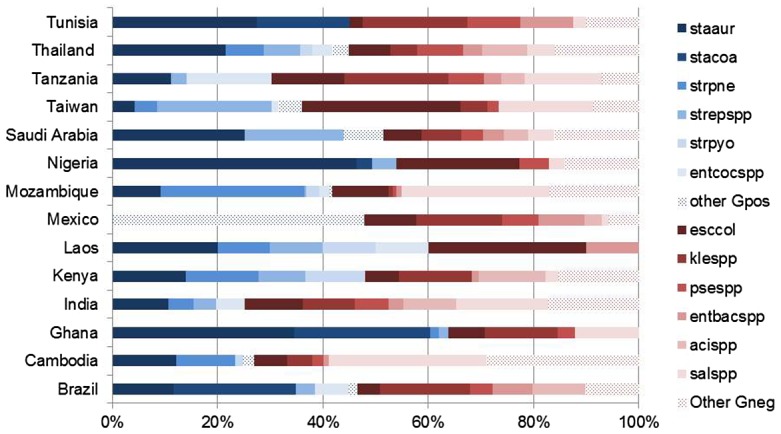

Regarding local variations, Figures 1 (neonates) and 2 (children) show the pathogen distribution for studies conducted in specific LMIC reported after 2005. These data demonstrate the heterogeneity likely to be encountered in settings for which the WHO essential medicines list is relevant. In particular, it is not presently possible to definitively delineate the specific role played by bacteria which are difficult to treat, e.g. Klebsiella spp. and Acinetobacter spp. The relative incidence of these pathogens may have a considerable impact on the probable cover by different empirical regimens as certain bacteria are intrinsically resistant or display high levels of acquired resistance to commonly used antibiotics, which lowers their coverage.

Figure 1.

Pathogen distribution for studies conducted in a specific setting and reported after 2005 in neonates.

Notes: Staaur, S. aureus; stacoa, coagulase-negative staphylococci; strepspp, streptococci; straga, S. agalactiae; entcocspp, enterococci; other Gpos, other Gram-positive pathogens; esccol, E. coli; klespp, klebsiella spp; psespp, pseudomonas spp; entbacspp, enterobacter spp; acispp, acinetobacter spp., other Gneg: other Gram-negative pathogens.

Figure 2.

Pathogen distribution for studies conducted in a specific setting and reported after 2005 in children.

Notes: Staaur, S. aureus; stacoa, coagulase-negative staphylococci; strpne, S. pneumonia; strepspp, streptococci; strpyo, S. pyogenes; entcocspp, enterococci; other Gpos, other Gram-positive pathogens; esccol, E. coli; klespp, klebsiella spp; psespp, pseudomonas spp; entbacspp, enterobacter spp; acispp, acinetobacter spp; salspp, salmonella spp; other Gneg, other Gram-negative pathogens.

Antimicrobial resistance patterns

Only very limited reliable data on antimicrobial susceptibility are available from Asia, Latin America and Africa. It is evident from existing summaries of the data that there is considerable antibiotic resistance to many commonly used antibiotics with variations both between and within regions in LMIC [57,60].

According to a systematic review and meta-analysis by Downie et al. [23], more than 40% of cases of community-acquired neonatal bacteraemia in LMIC are resistant or have reduced susceptibility to a combination of penicillin and gentamicin and to third-generation cephalosporins, thus suggesting that third-generation cephalosporins are no more effective in treating sepsis than the currently recommended antibiotics, benzylpenicillin and gentamicin. More than 35% of cases of community-acquired bacteraemia in infants aged 1–12 months are resistant or have reduced susceptibility to the combination of penicillin and gentamicin and to third-generation cephalosporins. In neonates, the gaps in antibiotic coverage with either benzylpenicillin/ampicillin and gentamicin or third-generation cephalosporins regimens were mostly in infections owing to enteric Gram-negative bacilli, particularly klebsiella spp. [23]. However, in the Pakistan SATT trial, it was reassuring that the majority of micro-organisms tested (32/37) were susceptible to gentamicin and amoxicillin [20].

Similar findings were reported in a 2015 systematic review of studies which estimated AMR rates in Gram-negative bloodstream infections in children in LMIC [58]. Gram-negative bacteria accounted for 67% of all episodes. The predominance of klebsiella spp. with a high prevalence of resistance to gentamicin in Asia (69%, Interquartile Range (IQR) 19–95%) and Africa (54%, IQR 0–68%) and the overall level of resistance of Gram-negative bacteria to third-generation cephalosporins (Asia 84%, IQR 45–95%; Africa 50%, IQR 0–87%) were very concerning.

All reviews published to date note the very low number of studies with adequate data. In particular, many of the studies reviewed had a high risk of bias with substantial uncertainty about how representative the data are for each setting. There are concerns that the data published are mainly from larger tertiary neonatal units, many of which might have higher rates of resistance owing to a nosocomial outbreak. In addition, virtually no clinical outcome data are reported (a finding confirmed by this review), particularly relating to the underlying disease, pathogen phenotype, empirical antibiotic treatment and clinical outcome. This imposes major limitations to selecting empirical regimens on the basis of their clinical impact.

Discussion

Since 2012, only suspected community neonatal sepsis has been addressed and there have been no adequate studies in other settings. Five adequately designed and powered studies which compared antibiotic treatments in a low-risk community setting in neonates and young infants (0–59 days) in LMICs were found [18–22]. They addressed potential simplifications of the current WHO treatment of reference, particularly for infants for whom admission to inpatient care was not acceptable or possible. In this group of infants, evidence suggests that treatment regimens could potentially be simplified, for example, by using injectable gentamicin for 2 days and oral amoxicillin for 7 days for young infants [22]. We hypothesise that the regimen of injectable gentamicin for 2 days and oral amoxicillin for 7 days would offer advantages over others investigated by requiring fewer invasive procedures with only two injections, promoting treatment adherence, and by allowing administration of high doses of aminoglycoside to target high MIC, while preventing drug accumulation over days and thus potential toxicity (mostly nephrotoxicity) based on a once-daily dosing regimen. However, these studies did not evaluate regimens and/or agents outside of those currently on the essential medicines list. Also, they were limited to a specific subpopulation of infants and children (≤59 days old, weight ≥ 1500 g) with suspected sepsis. Enrolment according to the diagnosis of PSBI was based on the presence of any sign of clinical severe infection except signs of critical illness (unconsciousness and convulsions) [19–22]. As it was a community-based, low-risk study, a considerable proportion of treated infants might not have had a bacterial infection. Indeed, in the single trial that performed blood cultures (Pakistan SATT trial), only 4% were positive for a pathogen [20]. It is also unclear what the rates of antimicrobial resistance were in these settings, but sensitivities to the aminoglycoside-based regimens are likely to be higher than in facility-based settings, and the results of susceptibility testing in the Pakistan SATT trial tend to confirm this, although the number of samples tested (37) was very low. In the Pakistan SATT, the presence of bacteraemia did not predict treatment failure in per-protocol infants [10 (13%) of 75 children with bacteraemia and 227 (12%) of 1618 without bacteraemia had treatment failure (risk difference 1.03, 95% CI −6.8 to 8.9)]. Overall, studies assessing the efficacy of specific antibiotic regimens in infants and children with blood culture-proven sepsis and/or the effectiveness of different regimens in infants and children with nosocomial sepsis are virtually lacking. Given the challenges of increasing levels of antibiotic resistance in LMIC (based on evaluation of blood cultures usually collected from inpatients or at least on presentation at hospital) and the considerable variation in the patterns of bacteria causing bacteraemia, for example, with the predominance of klebsiella spp. and acinetobacter spp., it might be expected that additional antibiotic options will be required. Closing the existing gaps in evidence must be made a priority so that any additions/changes to the recommended regimens are based on robust data. All the other trials addressing antibiotic regimens in neonatal and paediatric sepsis that were identified were disappointing in terms of design (often retrospective), power (low sample size) and outcomes (not performed in LMIC, method not always well-reported, drug dose often not reported). In addition, it is essential to have more data on causative pathogens and their susceptibilities in order to understand which treatment regimens could be effective and should be prioritised for further investigation. There are virtually no relevant studies with rigorous methods to direct therapeutic options in children. Fundamental concepts of effective antimicrobial therapy in critically ill children (proper culture techniques, timely initiation of therapy, selection of agents with a high likelihood of susceptibility and sufficient penetration to the site of infection, adequate doses and intervals to enhance bactericidal activity) are often impractical in LMIC owing to limited resources and infrastructure. Overall, a recommendation to amend the current WHO antibiotic regimens for PSBI cannot be made.

The utility of third-generation cephalosporins as second-line treatment is under debate based on the sparse microbiological surveillance data available. Additionally, there is major concern about the widespread use of third-generation cephalosporins and selection for multidrug Gram-negative infections in neonatal units. Further efforts are urgently needed to investigate alternative older off-patent therapeutic antimicrobials such as colistin, polymixin B or fosfomycin, to delineate their efficacy and safety in the paediatric population and to determine their potential contribution to antimicrobial regimens in LMIC settings.

In conclusion, current WHO guidelines which support the use of gentamicin and penicillin for inpatients or gentamicin (IM) and amoxicillin (IM, per os) when admission is not possible accord with currently available evidence and other international guidelines, and there is no strong evidence to change this guidance. The absence of almost any adequate evidence to suggest revision of the guidance for sepsis in hospital setting for neonates or any setting for children is a major concern.

Funding

This work was supported by Eckenstein-Geigy Foundation, Basel, Switzerland; World Health Organization, Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health, Switzerland.

Notes on contributors

Aline Fuchs is a researcher, University Children’s Hospital Basel, Switzerland. Her research interests include modeling and simulation in infectious disease and use of antibiotics in neonates.

Julia Bielicki is a researcher in infection and pharmacology at the University of Basel Children’s Hospital and at St George’s University London and a pediatric infectious disease specialist. Her research interests are making antimicrobial resistance surveillance data accessible for clinical decision-making, clinical trials addressing optimal management of bacterial infections in childhood and antibiotic stewardship.

Shrey Mathur is a researcher and clinician at St George’s, University of London. His research interests include implementation of evidence-based guidance, antibiotic prescribing, health service delivery, and global child health.

Mike Sharland is a professor of Paediatric Infectious Diseases and Lead Consultant Paediatrician at St George’s Hospital in London. His research interests include optimising the use of antimicrobials in children, developing the evidence base for paediatric antimicrobials and antimicrobial stewardship.

Johannes N. van den Anker is the Eckenstein-Geigy distinguished Professor of Paediatric Pharmacology, University of Basel Children’s Hospital, Switzerland. His research interests include developmental, neonatal and paediatric pharmacology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1]. Seale AC, Blencowe H, Manu AA, et al. Estimates of possible severe bacterial infection in neonates in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America for 2012: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:731–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Oza S, et al. Every newborn: progress, priorities, and potential beyond survival. Lancet. 2014;384:189–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet. 2016;388:3027–3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Zea-Vera A, Ochoa TJ. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of neonatal sepsis. J Trop Pediatr. 2015;61:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. World Health Organization Pocket book of hospital care for children: guidelines for the management of common illnesses with limited resources; 2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9241546700/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. World Health Organization Pocket book of hospital care for children: guidelines for the management of common illnesses with limited resources; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/child_hospital_care/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. World Health Organization Managing possible serious bacterial infection in young infants when referral is not possible; 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/bacterial-infection-infants/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Versporten A, Bielicki J, Drapier N, et al. The Worldwide Antibiotic Resistance and Prescribing in European Children (ARPEC) point prevalence survey: developing hospital-quality indicators of antibiotic prescribing for children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:1106–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Obiero CW, Seale AC, Berkley JA. Empiric treatment of neonatal sepsis in developing countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:659–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:165–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Caffrey Osvald E, Prentice P. NICE clinical guideline: antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of early-onset neonatal infection. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2014;99:98–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. NICE Sepsis: Recognition, Diagnosis and Early Management; Antibiotic Treatment in People with Suspected Sepsis; 2016. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng51/chapter/recommendations#antibiotic-treatment-in-people-with-suspected-sepsis [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases 30th ed In: Kimberlin DW, Bradley MT, Jackson MA, et al., editors. Red book. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Polin RA. Committee on fetus newborn. Management of neonates with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. PEDIATRICS. 2012;129:1006–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Brady MT, Polin RA. Prevention and management of infants with suspected or proven neonatal sepsis. PEDIATRICS. 2013;132:166–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. BMJ Best Practice Sepsis in Children; 2016. Available from: http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/1201/treatment/step-by-step.html [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Joint Formulary Committee , editors. In: Joint Formulary Committee Infection; blood infection, bacterial British national formulary for children. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press; 2015. p. 274. [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Zaidi AK, Tikmani SS, Warraich HJ, et al. Community-based treatment of serious bacterial infections in newborns and young infants: a randomised controlled trial assessing three antibiotic regimens. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:667–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Baqui AH, Saha SK, Ahmed AS, et al. Safety and efficacy of alternative antibiotic regimens compared with 7 day injectable procaine benzylpenicillin and gentamicin for outpatient treatment of neonates and young infants with clinical signs of severe infection when referral is not possible: a randomised, open-label, equivalence trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e279–e287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Mir F, Nisar I, Tikmani SS, et al. Simplified antibiotic regimens for treatment of clinical severe infection in the outpatient setting when referral is not possible for young infants in Pakistan (Simplified Antibiotic Therapy Trial [SATT]): a randomised, open-label, equivalence trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e177–e185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. African Neonatal Sepsis Trial group, Tshefu A, Lokangaka A, et al. Oral amoxicillin compared with injectable procaine benzylpenicillin plus gentamicin for treatment of neonates and young infants with fast breathing when referral is not possible: a randomised, open-label, equivalence trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1758–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. African Neonatal Sepsis Trial Group, Tshefu A, Lokangaka A, et al. Simplified antibiotic regimens compared with injectable procaine benzylpenicillin plus gentamicin for treatment of neonates and young infants with clinical signs of possible serious bacterial infection when referral is not possible: a randomised, open-label, equivalence trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1767–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Downie L, Armiento R, Subhi R, et al. Community-acquired neonatal and infant sepsis in developing countries: efficacy of WHO’s currently recommended antibiotics – systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Bibi S, Chisti MJ, Akram F, et al. Ampicillin and gentamicin are a useful first-line combination for the management of sepsis in under-five children at an urban hospital in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;30:487–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Ramasamy S, Biswal N, Bethou A, et al. Comparison of two empiric antibiotic regimen in late onset neonatal sepsis – a randomised controlled trial. J Trop Pediatr. 2014;60:83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Chong E, Reynolds J, Shaw J, et al. Results of a two-center, before and after study of piperacillin–tazobactam versus ampicillin and gentamicin as empiric therapy for suspected sepsis at birth in neonates ≤1500 g. J Perinatol. 2013;33:529–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Cantey JB, Lopez-Medina E, Nguyen S, et al. Empiric antibiotics for serious bacterial infection in young infants: opportunities for stewardship. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:568–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Paul M, Lador A, Grozinsky-Glasberg S, et al. Beta lactam antibiotic monotherapy versus beta lactam-aminoglycoside antibiotic combination therapy for sepsis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD003344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Tamma PD, Turnbull AE, Harris AD, et al. Less is more: combination antibiotic therapy for the treatment of gram-negative bacteremia in pediatric patients. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:903–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Berkowitz NM, Spaeder MC, DeBiasi RL, et al. Empiric monotherapy versus combination therapy for enterobacteriaceae bacteremia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:1203–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Sick AC, Tschudin-Sutter S, Turnbull AE, et al. Empiric combination therapy for gram-negative bacteremia. PEDIATRICS. 2014;133:e1148–e1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Tewari VV, Jain N. Monotherapy with amikacin or piperacillin-tazobactum empirically in neonates at risk for early-onset sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. J Trop Pediatr. 2014;60:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Rodriguez-Guerineau L, Salvia-Roigés MD, León-Lozano M, et al. Combination of vancomycin and rifampicin for the treatment of persistent coagulase-negative staphylococcal bacteremia in preterm neonates. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:693–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Turnidge J. Pharmacodynamics and dosing of aminoglycosides. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:503–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Kent A, Turner MA, Sharland M, et al. Aminoglycoside toxicity in neonates: something to worry about? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12:319–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Fuchs A, Zimmermann L, Bickle Graz M, et al. Gentamicin exposure and sensorineural hearing loss in preterm infants. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0158806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Musiime GM, Seale AC, Moxon SG, et al. Risk of gentamicin toxicity in neonates treated for possible severe bacterial infection in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic Review. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20:1593–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Botha JH, du Preez MJ, Miller R, et al. Determination of population pharmacokinetic parameters for amikacin in neonates using mixed-effect models. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;53:337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Giotis ND, Baliatsa DV, et al. Extended-interval aminoglycoside administration for children: a meta-analysis. PEDIATRICS. 2004;114:e111–e118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. de Hoog M, Mouton JW, Schoemaker RC, et al. Extended-Interval dosing of tobramycin in neonates: implications for therapeutic drug monitoring. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;71:349–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Fattinger K, Vozeh S, Olafsson A, et al. Netilmicin in the neonate: population pharmacokinetic analysis and dosing recommendations. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1991;50:55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Freeman CD, Nicolau DP, Belliveau PP, et al. Once-daily dosing of aminoglycosides: review and recommendations for clinical practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Bijleveld YA, van den Heuvel ME, Hodiamont CJ, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and dosing considerations for gentamicin in newborns with suspected or proven sepsis caused by gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e01304–e01316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Valitalo PA, van den Anker JN, Allegaert K, et al. Novel model-based dosing guidelines for gentamicin and tobramycin in preterm and term neonates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2074–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Wilbaux M, Fuchs A, Samardzic J, et al. Pharmacometric approaches to personalize use of primarily renally eliminated antibiotics in preterm and term neonates. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56:909–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Barker CI, Germovsek E, Sharland M. What do I need to know about penicillin antibiotics? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2017;102:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Donnelly PC, Sutich RM, Easton R, et al. Ceftriaxone-associated biliary and cardiopulmonary adverse events in neonates: a systematic review of the literature. Paediatr Drugs. 2017;19:21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Germovsek E, Barker CI, Sharland M. What do I need to know about aminoglycoside antibiotics? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2017;102:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Kuehn J, Ismael Z, Long PF, et al. Reported rates of diarrhea following oral penicillin therapy in pediatric clinical trials. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2015;20:90–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Monte SV, Prescott WA, Johnson KK, et al. Safety of ceftriaxone sodium at extremes of age. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008;7:515–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Pichichero ME, Zagursky R. Penicillin and cephalosporin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52]. Roberts JK, Stockmann C, Constance JE, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antibacterials, antifungals, and antivirals used most frequently in neonates and infants. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53:581–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53]. Salvo F, De Sarro A, Caputi AP, et al. Amoxicillin and amoxicillin plus clavulanate: a safety review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54]. Santos RP, Tristram D. A practical guide to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of neonatal infections. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62:491–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55]. Tripathi N, Cotten CM, Smith PB. Antibiotic use and misuse in the neonatal intensive care unit. Clin Perinatol. 2012;39:61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56]. Greenhow TL, Hung YY, Herz AM. Changing epidemiology of bacteremia in infants aged 1 week to 3 months. PEDIATRICS. 2012;129:e590–e596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57]. Huynh BT, Padget M, Garin B, et al. Burden of bacterial resistance among neonatal infections in low income countries: how convincing is the epidemiological evidence? BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58]. Le Doare K, Bielicki J, Heath PT, et al. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance rates among gram-negative bacteria in children with sepsis in resource-limited countries. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2015;4:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59]. Hamer DH, Darmstadt GL, Carlin JB, et al. Etiology of bacteremia in young infants in six countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:e1–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60]. Ashley EA, Lubell Y, White NJ, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial isolates from community acquired infections in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asian low and middle income countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:1167–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]