Abstract

Purpose

The increasing demand for primary eye care due to an aging population implicates an enhanced role of optometrists in the communities. The primary objective of this study was to investigate the rate of referrals and returning medical reports between optometrists and health care professionals in Norway. The secondary objectives were to investigate the conformity of diagnoses in referrals and medical reports, the extent of optometric follow-up examinations and the use of ophthalmic diagnostic drugs in optometric practice.

Materials and methods

This study is an ongoing prospective electronic survey administered on the Internet between November 2014 and December 2017. Optometrists in private optometric practice are eligible. Participants register data for up to 1 year, including examinations and the use of ophthalmic diagnostic drugs; referrals, including International Classification of Primary Care, second edition (ICPC-2) codes; medical reports, including the ICD-10 codes; and optometric follow-up enquiries. Analysis of agreement between referred and diagnosed conditions was made possible by encoding patients’ ID.

Results

Seventeen months into the study, 67 optometrists were included (Female: 60%, mean age: 41 years.). There were 49,510 registered examinations (60% general, 28% contact lens, 12% auxiliary). Diagnostic drugs were used in 4% of these and in 14% of the examinations that resulted in a referral. There were 1,779 referrals (97% to ophthalmologists). Top three diagnoses were cataract (36%), glaucoma (11%), and age-related macular degeneration (7%). There were 1,036 returned medical reports, of which 76% could be linked with registered referrals. Diagnostic agreement was observed in 80% of the cases (74% for primary diagnoses). There were only 17 registered cases of optometric follow-ups.

Conclusion

In Norway, nearly all referrals from optometrists are to ophthalmologists. More than half of these result in a returned medical report. Nonreturned reports do not seem to trigger optometric follow-ups. The diagnostic agreement between referrals and medical reports is high. Diagnostic ophthalmic drugs are used sparsely by optometrists and mostly in relation to referrals.

Keywords: optometry, ophthalmology, diagnostic, agreement, drugs

Introduction

The Norwegian eye care system consists of ~350 ophthalmologists,1 40 orthoptists2 and 1500 optometrists.3 Thus, optometry is the largest profession of the eye care system. Optometric practices are found in most of the 428 Norwegian municipalities and are generally less confined to urban areas than ophthalmologic practices. Optometric practice is regulated by the Health Personnel Act.4 Optometrists provide primary eye care services and refer patients, when appropriate, directly to an ophthalmologist,5 to a general practitioner or to other health care services where necessary and possible (section 4 in the Health Personnel Act).4 Approximately 53% of the positions in ophthalmology (full-time equivalent) are in private practice.1 In optometry, the corresponding number is ~97%.6 Hence, the Norwegian eye care is to a large extent run within the private sector. The optometric profession in Norway has changed over the past decades, from being a handcraft profession to health care profession in 1988, with rights to use ophthalmic diagnostic drugs in 2004. The educational background of Norwegian optometrists ranges from earlier training with a technical emphasis to the current training with a health-centered emphasis (BSc and MSc).

In 2010, the Coordination Reform was adopted with the intention of providing better distribution of workload between the municipalities and specialist health care services in Norway.7 Optometric service is not a part of the municipal health services but is, by far, the major provider of primary health care services in Norwegian eye care. Nonetheless, little is known about the extent and quality of the interaction between optometrists and ophthalmologists in the Norwegian eye care system. The Norwegian Health Economics Administration (The Norwegian Health Economics Administration [HELFO] is a subordinate institution directly linked to the Norwegian Directorate of Health. https://helsedirektoratet.no/English) does not provide statistics related to these issues. Instead, information is often restricted to anecdotal examples suggesting widespread problems with referrals that are unnecessary (over-referrals), unclear or insufficient. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to investigate the rate of referrals and returning medical reports between optometrists and other health care professionals in Norway. The secondary objectives were to investigate the conformity of diagnoses in referrals and medical reports, the extent of optometric follow-up enquiries and the use of diagnostic drugs in optometric practice.

Materials and methods

This study is an ongoing prospective electronic survey administered on the Internet between November 2014 and December 2017. Optometrists who hold a membership in the Norwegian Association of Optometrists and who work in private optometric practice in Norway are eligible. This corresponds to ~1090 optometrists (personal communication Per Kristian Knutsen, Synsinformasjon [Optical Information Council Norway]). Invitation to participate is via announcements in professional journals, via emails and on the website of the professional organization. Optometrists who are not seeing patients on a regular basis or who are working in public or private non-optometric practice, for example, specialist eye care, are excluded. Optometrists who are interested in participating in the study are directed to a recruitment website where the inclusion criteria are listed together with an informed consent. The optometrist is requested to confirm by tick boxes that she/he fulfills the inclusion criteria, and has read and understood the informed consent before submitting an agreement to participate in the study. A confirmatory mail is sent to the optometrist with a link to a personal survey website, a copy of the informed consent and a personal password for logging on. Participation in the study is voluntary, and the optometrist may withdraw her/his consent at any time without giving reason.

Participants register data for up to 1 year. A prospective open cohort design permits recruitment and data collection over a period of 3 years. The survey is administered via the Internet using a password-protected and user-friendly website for the registration of 1) all optometric examinations and the use of ophthalmic diagnostic drugs; 2) all referrals to health care professionals, including diagnoses (International Classification of Primary Care, second edition [ICPC-2]8 codes with supplementary text); 3) all medical reports, including diagnoses (International Classification of Disease, tenth edition [ICD-10]9 codes with supplementary text) and 4) all follow-up examinations of referred patients lacking medical reports. Participants were unidentified using ID numbers. To allow for the analyses of agreement of diagnoses in referrals and medical reports, patients were encoded using the same patient ID as in the local clinical journal. The website and associated database are owned and administered by the Optical Information Council Norway (Synsinformasjon). At regular intervals, data are downloaded and organized in a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel). Analysis of diagnostic agreement was based on a subjective assessment of the concordance of diagnostic codes and texts in referrals and medical reports, made by the two authors together (POL, KL). The criteria included official conversion keys for ICPC-2 and ICD-10 codes provided by the Norwegian Directorate of Health10 and a set of interpretation criteria created with the purpose of retaining the consistence of assessments. Repeated analyses after 4 months revealed a kappa index of 0.8. Diagnostic agreement was assessed for primary diagnoses of referrals and medical reports and for primary diagnoses of referrals and primary and secondary diagnoses of medical reports. Data were thereafter transferred to a statistical analysis software (SPSS, v.24, IBM). Descriptive analysis of data included means and proportions with confidence intervals and medians with ranges. Statistical significance was set at a level of p<0.05 (two-sided test). The study was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics and the Norwegian Social Science Data Services.

Results

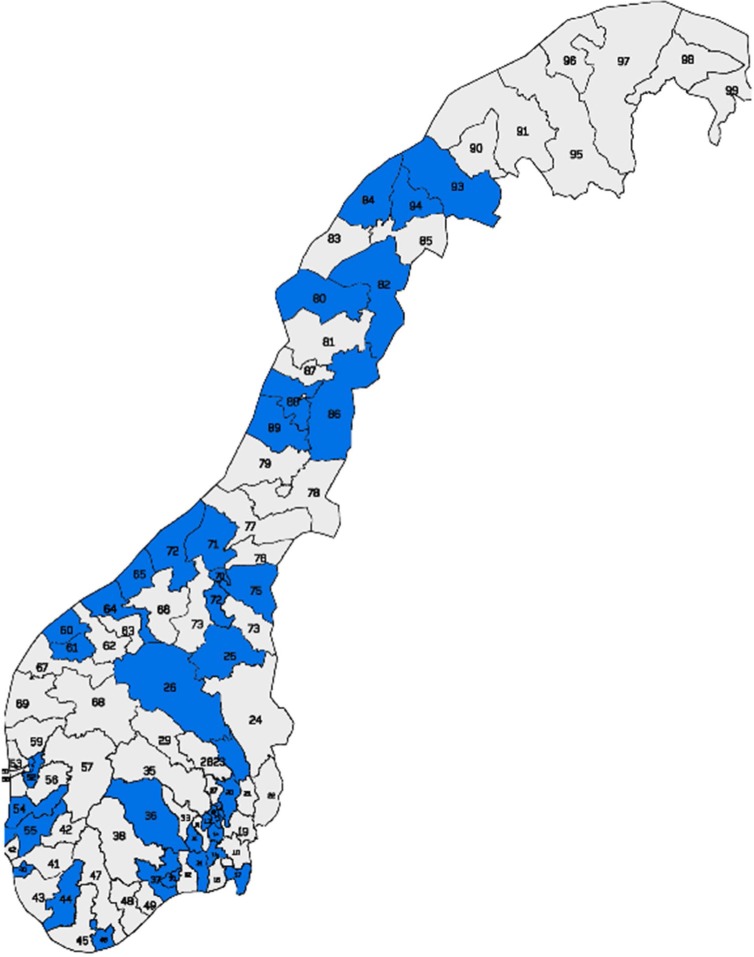

Halfway through the study period (as of May 2016), 67 optometrists (n=40, 59.7% female) had completed the study. The average time of participation in the open cohort was 229 days (SD 150 days) at the time of analysis. Figure 1 shows the geographical distribution of participating optometrists. The mean age was 41.1 years (SD 9.8 years, range 24–64 years). Male optometrists were on average 7.0 years older than female optometrists (p<0.01). All participants were authorized to fit contact lenses, whereas 65 of 67 (97.0%) were authorized to use ophthalmic diagnostic drugs. There were 20 participants with BSc degree (29.9%), 33 with MSc degree (49.3%) and 14 with an earlier training (20.9%).

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of participating optometrists (blue).

Note: Modified map of postcode regions in Norway adapted with permission from Posten Norge AS from Bring. Finding New Ways. Postnummerregioner. Bring PKM-234-A4. Available from http://www.bring.no/_attachment/333492/binary/204175?download=true. Accessed May 16, 2017.21

In total, there were 49,510 examinations registered in the study. A total of 29,474 (59.5%) were general optometric eye examinations, 14,022 (28.3%) were contact lens examinations and 6,014 (12.1%) were auxiliary examinations. Optometrists performed on average 6.0 (SD 2.9) optometric examinations per person workday. When short working days were excluded from the data, the rate increased to 6.4 (SD 2.9) optometric examinations per person workday.

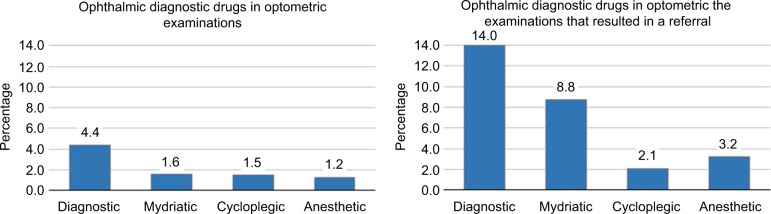

The use of ophthalmic diagnostic drugs among participants with rights to use these drugs is shown in Figure 2. The percentage use of ophthalmic diagnostic drugs in optometric examinations was 4.4%. This corresponds to a rate of use of diagnostic drugs in approximately every 23rd examination. Mydriatics were used in 1.6%, cycloplegics in 1.5% and topical anesthetics in 1.2% of the examinations. The use of diagnostic drugs in eye examinations that resulted in a referral was 14.0%, which corresponds to a rate of use of diagnostics in approximately every seventh examination. The use of diagnostics in relation to referrals was 7.2% greater for mydriatics but only 0.6% greater for cycloplegics and 2.0% greater for anesthetics compared with optometric examinations.

Figure 2.

Percentage use of ophthalmic diagnostic drugs in optometric examinations (left) and in optometric examinations that resulted in a referral (right). Values are rounded.

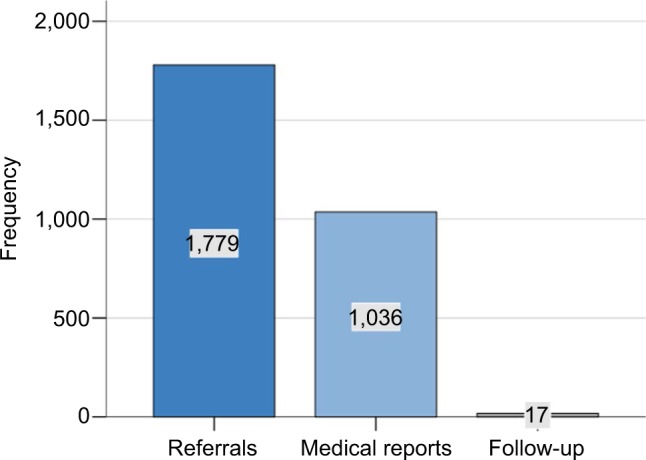

Figure 3 shows the distribution of referrals, medical reports and follow-up enquiries. The total number of referrals (n=1,779) corresponds to 3.6% of all eye examinations or a referral at approximately every 28th examination. A total of 1,227 (69.4%) of the referrals were addressed to ophthalmologists in private practice, whereas 494 (28.0%) were addressed to ophthalmologists in public hospitals. There were 25 (1.4%) referrals to general practitioners, 10 (0.6%) to orthoptists, 7 (0.4%) to optometrist colleagues and 3 (0.2%) to other health care professions.

Figure 3.

Distribution of referrals, medical reports and follow-up enquiries.

A total of 1,036 medical reports were registered (Figure 3). Of these, 979 (94.5%) were medical reports that were related to referrals in the study period (78.2%) or referrals prior to the study period (16.3%). The remaining 57 (5.5%) were medical reports with a content that could not be related to a prior referral. Thus, the number of returned medical reports was 55.0% of the number of sent referrals. Out of 979 medical reports, 791 (80.1%) were possible to match with a referral in the study. The average time from a referral to a returned medical report was 73.7 days (SD 69.7 days). There were only 17 registered cases of follow-up enquiries of referrals with missing medical reports.

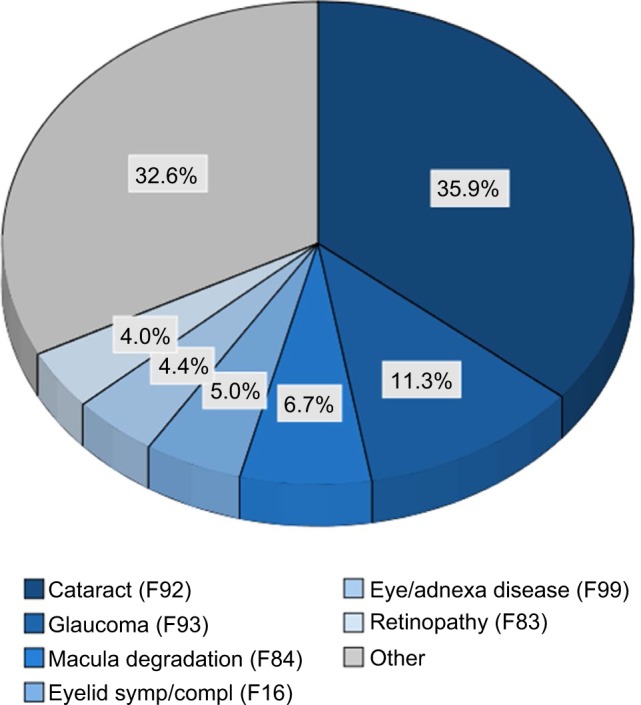

The five most commonly referred diagnostic groups are shown in Figure 4. Cataract (ICPC-2 code F92) is the largest referred group (35.9%), followed by glaucoma (F93, 11.3%), macula degeneration (F84, 6.7%), eyelid symptoms and complaints (F16, 5.0%), eye/adnexa disease (F99, 4.4%) and retinopathy (F83, 4.0%).

Figure 4.

Proportion of referral diagnoses (ICPC-2 code).

Notes: Groups <4% are collapsed as “other”. This includes 44 different diagnoses, of which the five most frequent were strabismus (F95, 3.7%), detached retina (F82, 3.0%), eye symptom/complaint other (F29, 2.7%) and visual disturbance other (F05, 1.4%). Values are rounded.

Abbreviations: ICPC-2, International Classification of Primary Care, second edition; symp, symptom; compl, complaint.

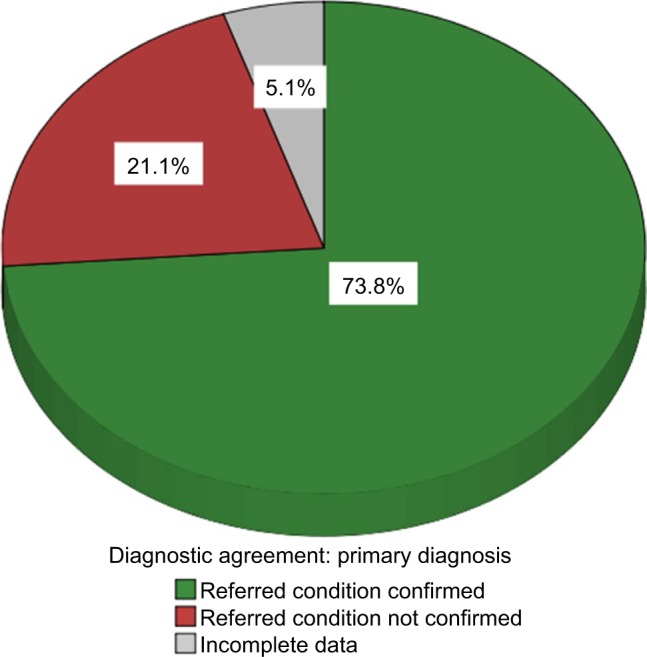

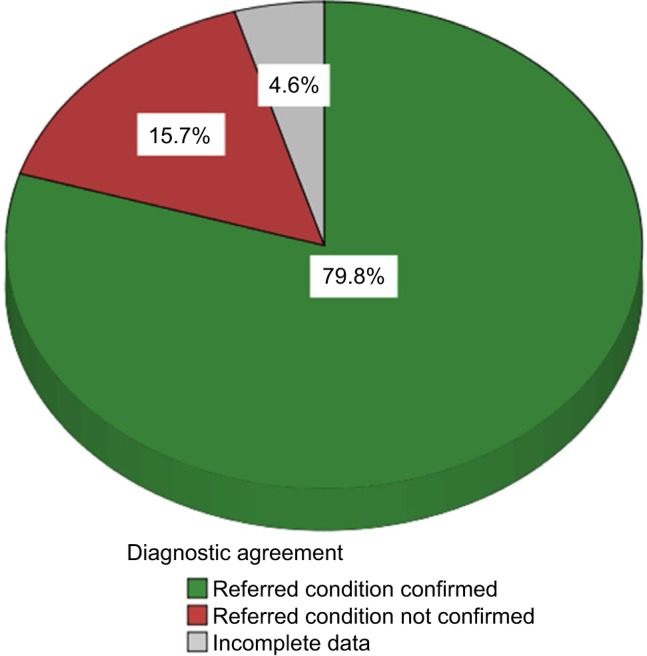

Results from the analysis of agreement between the referred condition (diagnoses in referrals) and the diagnosed condition (diagnoses in medical reports) are shown in Figures 5 and 6. Optometrists’ primary referral diagnosis matched with the primary medical report diagnosis in 73.8% and mismatched in 21.1% of the cases (Figure 5). However, if optometrists’ primary referral diagnoses were compared with both primary and secondary diagnoses in the medical reports, the match increased to 79.8% (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Proportion of diagnostic agreement with regard to primary diagnoses.

Note: Values are rounded.

Figure 6.

Proportion of diagnostic agreement with regard to primary and secondary diagnoses.

Note: Values are rounded.

Discussion

Preliminary results indicate that optometrists in Norway perform on average six optometric examinations per day and that 3.6% of these, or approximately every 28th examination, result in a referral to other health care professionals, mainly ophthalmologists. A referral rate of 3.6% is in the lower range of previous reports (2%–14%)11,12 and diverge from 6% that was found in a cross-sectional study in optometric practice in Norway in 2007.13 Discrepancies may reflect differences between studies in the distribution of patients, the setting of optometric practices and educational background of optometrists. The prospective design of the reported study favors a valid estimate of the proportion of referrals. However, the sample in the reported study was overrepresented by optometrists with a higher educational background (BSc and MSc) compared with the underlying population of optometrists (82% vs. 47% personal communication Per Kristian Knutsen, Synsinformasjon [Optical Information Council Norway]). Post hoc comparison of the effect of educational background on referral rates indicates higher rates among participants with former educational background. In addition, the infrequent number of referrals to general practitioners (only 25 patents) is considerably less than that found in comparable studies (15–72%),12,14 but similar to estimated rate (1.7%) in a meta-analysis of 15 research studies.11 Hence, it is reasonable to conclude that the true referral rate from optometrists in Norway may be >3.6% found in the reported study. The very low rate of referrals to other optometrists is considerably <8% found in the UK,14 which may suggest an underuse of the competency between colleagues in Norwegian optometry.

The three most frequent self-reported conditions referred to ophthalmologists, counting for more than half of all registered referrals, were cataract followed by glaucoma and macular degeneration. Findings are in close agreement with other studies as regards the two most frequently referred conditions,11,12,15 but differs for the third where other conditions such as binocular conditions and anterior eye, lid and adnexa conditions have been reported.11,12 The reason for this divergence may be related to miscoding of certain conditions using the ICPC-2 system. Post hoc analyses of ICPC-2 codes in the subsample of referrals that matched with returned medical reports indicated miscoding in 15.8% of cases. In particular was F99 (eye/adnexa disease) underused. When the subsample was corrected for appropriate ICPC codes, considering both the written information about the condition in the referral and the diagnosed condition in the medical report, the most frequent conditions referred to ophthalmologists were cataract (34.2%), followed by glaucoma (11.1%), eye/adnexa disease (F99, 10.9%) and macular degeneration (9.4%).

Medical reports include a written summary and a final adjudication of a case of disease, with information on diagnosis, treatment and subsequent follow-up examinations. Preliminary results indicated that the rate of medical reports to optometrists was slightly more than half the rate of referrals over a period of on average 223 days. The rates of returned feedback to optometrists have been found to be as low as 12%–17% in countries where such information requires the patient’s consent.14,16 Nonetheless, because medical reports are statutory in the Norwegian Health Care System,5 a seemingly reasonable rate of 55% may indicate a need for improved two-way communication between optometrists and ophthalmologists. In general, low rates of returned feedback to optometrists in the community are unfortunate as the feedback may be an important parameter in the continuous training of optometrists in disease detection and referral refinement.17 In addition, the information included in referrals and medical reports helps clarify responsibilities and ensures that follow-up is performed in the patient’s best interest. However, the fact that there were only 17 cases of registered follow-up enquiries of referrals with missing medical reports suggests that this may not be perceived as a problem among optometrists in Norway.

Agreement between referred and diagnosed conditions was found in nearly 80% of the matched pairs of referrals and medical reports. However, when the referred condition was compared with the primary diagnosed condition only, the number dropped to 74%. This number is close to a concurrence of 67%–76% found in studies that have investigated the accuracy of referrals from optometrists to ophthalmologists in the UK.18,19 The difference in concurrence found in the reported study may indicate that refinement of referrals as regards the priority of referred conditions may improve the diagnostic agreement by as much as 6%.

Ophthalmic diagnostic drugs were used in 4.4% of the examinations. By comparison, the rate of use of ophthalmic diagnostic drugs in Norwegian optometric practice was 2% in 2004 when the legislation of ophthalmic diagnostic drugs came into force. Thus, the change of diagnostic procedures has been modest since the introduction of ophthalmic diagnostic drug in Norwegian optometric practice. Unfortunately, comparative studies are scarce, which makes it difficult to assess what would be an acceptable rate of use. In a survey of the scope of practice by UK optometrists in 2008, the frequent use of mydriatics was reported by 91% of responders, followed by cycloplegics (50%) and anesthetics (30%).20 However, the rate of use that corresponded with the frequent use was not defined in this study. In another survey of optometric practice in the US, dilated fundus examinations were performed for 40% of all types of patients and for 48% of patients that received a routine eye examination.14 Differences in the legislation set aside, optometrists in the UK, the US and Norway are primary health care providers and have access to ophthalmic diagnostic drugs to facilitate certain diagnostic investigations. Hence, it is reasonable to conclude that the rate of use found in Norway reflects a true underuse of ophthalmic diagnostic drugs, despite the higher rate observed for examinations in conjunction with referrals. Considering the fact that the top three referred conditions would require dilatation for a proper standard diagnostic assessment, the expected rate of use would have been at least 50% in the reported study.

The strengths of the study include a prospective study design that favors accurate rendition of information on referrals and returned medical reports, and an open cohort that makes it possible to obtain data for participants who enter and leave the study at different times with different lengths of participation. The main limitations of the study are the inherited uncertainty of self-reported data and a restricted sample of participating optometrists. The prospective design with registration of activity for a period of up to 1 year may have reduced the effect of recall bias; however, it may not have prevented information bias, in particular, related to diagnostic data in referrals and medical reports. Although efforts were made to reduce this effect by information and reminders to participants during data collection and by exclusion of insufficient data in the analyses of diagnostic agreement, results must be interpreted with this weakness in mind. In addition, the small sample of participating optometrists in the reported study may not be representative of the underlying population of optometrists in Norway. Hence, the risk of a selection bias should be considered when extrapolating the results.

Conclusion

Preliminary results indicate that in Norway, nearly all referrals from optometrists are to ophthalmologists. More than half of these result in a returned medical report. However, nonreturned reports do not seem to trigger optometric follow-ups, which were infrequently reported. The diagnostic agreement between referrals and medical reports is high and improves further when the referred conditions are compared with any of the diagnosed conditions in the returned medical reports. Norwegian optometrists use ophthalmic diagnostic drugs sparingly, and mostly in relation to referrals.

Acknowledgments

The study is supported by Optical Information Council Norway. We are grateful for the technical and intellectual input of Mr. Per Kristian Knutsen in the development and administration of the web-based survey.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kartlegging og Oftalmologisk Nasjonal Utredning av framtidig Status [Ophthalmological National Assessment of Future Status] the Norwegian Society of Ophthalmology; (KONUS-Report 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norwegian Association of Orthoptists [webpage on the Internet] [Accessed April 27, 2017]. Available from: http://scandinavianorthoptist.org/side2.html.

- 3.The European Council of Optometry and Optics [webpage on the Internet] ECOO Blue Book. 2015. [Accessed April 27, 2017]. Available from: http://www.ecoo.info/2015/04/03/ecoo-publishes-blue-book-2015/

- 4.Helsepersonelloven [Act of 2nd July 1999, no 64 relating to health personnel etc] [Accessed April 27, 2017]. Available from: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-64?q=helsepersonelloven.

- 5.Forskrift om stønad til dekning av utgifter til undersøkelse og behandling hos lege [Regulations concerning grants to cover expenses for examination and treatment by a doctor]. FOR-2016-06-27-819. [Accessed April 27, 2017]. Available from: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2016-06-27-819.

- 6.Årsmelding 2016 Synsinformasjon [Annual Report 2016, Optical Information Council Norway] Oslo, Norway: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samhandlingsreformen [The Coordination Reform]: St.meld. 47. 2008–2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet] International Classification of Primary Care. Second Edition. 2003. [Accessed April 27, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/adaptations/icpc2/en/

- 9.World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet] International Classification of Disease. Tenth Edition. [Accessed April 27, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/

- 10.The Norwegian Directorate of eHealth [webpage on the Internet] Koderegisterfiler og konverteringsfiler [Code Registry Files and Conversion Files] [Accessed April 27, 2017]. Available from: https://ehelse.no/standarder-kodeverk-og-referansekatalog/helsefaglige-kodeverk/icpc-2-den-internasjonale-klassifikasjonen-for-primerhelsetjenesten.

- 11.Brin NJ, Griffin JR. Referrals by optometrists to ophthalmologists and other providers. J Am Optom Assoc. 1995;66(3):154–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobbelsteyn D, McKee K, Bearnes RD, Jayanetti SN, Persaud DD, Cruess AF. What percentage of patients presenting for routine eye examinations require referral for secondary care? A study of referrals from optometrists to ophthalmologists. Clin Exp Optom. 2015;98(3):214–217. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundling V, Gulbrandsen P, Bragadottir R, Bakketeig LS, Jervell J, Straand J. Optometric practice in Norway: a cross-sectional nationwide study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85(6):671–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soroka M, Krumholz D, Bennett A, National Board of Examiners Conditions Domain Task Force The practice of optometry: national board of examiners in optometry survey of optometric patients. Optom Vis Sci. 2006;83(9):E625–E636. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000236028.23657.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ewans BJW, Harle DE, Cocco B. Optometric referrals: towards a two way flow of information? Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(12):1663. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.075531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whittaker KW, Ikram K, Anderson DF, Kiel AW, Luff AJ. Non-communication between ophthalmologists and optometrists. J R Soc Med. 1999;92(5):247. doi: 10.1177/014107689909200509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blank L, Baxter S, Buckley Woods H, Goyder E. What is the evidence on interventions to manage referral from primary to specialist non-emergency care? A systematic review and logic model synthesis. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2015;3(24):2050–4349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierscionek TJ, Moore JE, Pierscionek BK. Referrals to ophthalmology: optometric and general practice comparison. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2009;29(1):32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2008.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fung M, Myers P, Wasala P, Hirji N. A review of 1000 referrals to Wallsall’s hospital eye service. J Public Health. 2016;38(3):599–606. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Needle JJ, Petchey R, Lawrenson JG. A survey of the scope of therapeutic practice by UK optometrists and their attitudes to an extended prescribing role. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2008;28(3):193–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2008.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bring Finding New Ways. Postnummerregioner. [Accessed May 16, 2017]. (Bring PKM-234-A4). Available from http://www.bring.no/_attachment/333492/binary/204175?download=true.