ABSTRACT

The high blood–O2 affinity of the bar-headed goose (Anser indicus) is an integral component of the biochemical and physiological adaptations that allow this hypoxia-tolerant species to undertake migratory flights over the Himalayas. The high blood–O2 affinity of this species was originally attributed to a single amino acid substitution of the major hemoglobin (Hb) isoform, HbA, which was thought to destabilize the low-affinity T state, thereby shifting the T–R allosteric equilibrium towards the high-affinity R state. Surprisingly, this mechanistic hypothesis has never been addressed using native proteins purified from blood. Here, we report a detailed analysis of O2 equilibria and kinetics of native major HbA and minor HbD isoforms from bar-headed goose and greylag goose (Anser anser), a strictly lowland species, to identify and characterize the mechanistic basis for the adaptive change in Hb function. We find that HbA and HbD of bar-headed goose have consistently higher O2 affinities than those of the greylag goose. The corresponding Hb isoforms of the two species are equally responsive to physiological allosteric cofactors and have similar Bohr effects. Thermodynamic analyses of O2 equilibrium curves according to the two-state Monod–Wyman–Changeaux model revealed higher R-state O2 affinities in the bar-headed goose Hbs, associated with lower O2 dissociation rates, compared with the greylag goose. Conversely, the T state was not destabilized and the T–R allosteric equilibrium was unaltered in bar-headed goose Hbs. The physiological implication of these results is that increased R-state affinity allows for enhanced O2 saturation in the lungs during hypoxia, but without impairing O2 delivery to tissues.

KEY WORDS: High-altitude, Blood, Oxygen transport, Allostery, Adaptation, Hypoxia

Summary: We unravel the functional mechanism responsible for the adaptive increase in hemoglobin–oxygen affinity and its allosteric regulation in bar-headed goose, a hypoxia-tolerant species renowned for its high-altitude migratory flights.

INTRODUCTION

Using flight paths that crest the Himalayas, bar-headed geese (Anser indicus) make a roundtrip annual migration between summer breeding grounds in Central Asia and wintering grounds on the Indian subcontinent (Bishop et al., 2015; Hawkes et al., 2013, 2011). Given the high energetic costs of flapping flight (Ward et al., 2002), the ability of bar-headed geese to fly at extreme elevations has earned them the respect of comparative physiologists and mountaineers alike (Hochachka and Somero, 2002; Scott, 2011; Scott et al., 2015). The physiological capacity of bar-headed geese for high-altitude flight derives from modifications of numerous convective and diffusive steps in the O2-transport pathway (Scott, 2011; Scott et al., 2015). One of the best-documented physiological adaptations of this hypoxia-tolerant species involves an increase in hemoglobin (Hb)–O2 affinity (Black and Tenney, 1980; Jessen et al., 1991; Meir and Milsom, 2013; Natarajan et al., 2018; Petschow et al., 1977; Weber et al., 1993). The elevated Hb–O2 affinity plays a key role in hypoxia adaptation by enhancing pulmonary O2 loading, which helps to maintain a high arterial O2 saturation in spite of the reduced O2 partial pressure (PO2) of inspired air (Scott and Milsom, 2006). The fact that bar-headed geese have evolved a derived increase in Hb–O2 affinity relative to lowland congeners, such as the greylag goose (Anser anser), is consistent with a general trend, as avian taxa native to extremely high elevations tend to have higher Hb–O2 affinities than their lowland relatives (Galen et al., 2015; Natarajan et al., 2016, 2015; Projecto-Garcia et al., 2013; Storz, 2016; Zhu et al., 2018).

Previous studies of bar-headed goose Hb have focused exclusively on the major HbA isoform (α2Aβ2A), which typically accounts for 70–80% of total Hb in the adult red blood cells of waterfowl species, with the minor HbD isoform (α2Dβ2A) accounting for the remaining fraction (Grispo et al., 2012; Natarajan et al., 2015; Opazo et al., 2015). Protein-engineering studies have demonstrated that the increased O2 affinity of bar-headed goose HbA is largely attributable to a rare substitution at the intradimer α1β1 interface of the tetrameric HbA, αA119Pro→Ala (Jessen et al., 1991; Weber et al., 1993), but two other α-chain substitutions, αA18Gly→Ser and αA63Ala→Val, also make sizable contributions (Natarajan et al., 2018). Perutz (1983) noted that the αA119Pro→Ala substitution eliminates a van der Waals interaction between αA119Pro and βA55Leu, residues located on opposing subunits of the same α1β1 interface, and suggested that the loss of this atomic contact destabilizes the low-affinity tense (T)-state conformation of the Hb tetramer. According to the two-state Monod–Wyman–Changeaux (MWC) allosteric model (Monod et al., 1965), destabilization of the low-affinity T state (the prevailing conformation of deoxy Hb) has the effect of shifting the T–R allosteric equilibrium between the two quaternary conformations in favor of the high-affinity relaxed (R) state (the prevailing conformation of oxy Hb). Thus, according to Perutz's hypothesis (Perutz, 1983), the increased O2 affinity of bar-headed goose HbA is caused by a single, large-effect substitution that reduces the MWC allosteric constant L (the ratio of the two conformational states [T]/[R] of deoxy Hb) and increases the O2 association equilibrium constant for T-state Hb, KT. According to this mechanism, the O2 association equilibrium constant for R-state Hb, KR, should remain unaltered.

Although this postulated mechanism for high-altitude adaptation has never been tested in native Hbs, early experiments involving recombinant human Hb with the engineered αA119Pro→Ala mutation appeared to support Perutz's hypothesis (Jessen et al., 1991; Weber et al., 1993). Nonetheless, there are reasons to suspect that our understanding of the mechanistic basis of this classic example of biochemical adaptation is still far from complete. First, given the function-altering effects of the other αA-chain substitutions, αA18Gly→Ser and αA63Ala→Val (Natarajan et al., 2018), information about the effects of αA119Pro→Ala alone cannot be expected to provide a complete picture. Second, mutagenesis experiments have revealed that identical Hb mutations often have different functional effects on different genetic backgrounds (Kumar et al., 2017; Natarajan et al., 2013; Storz, 2018; Tufts et al., 2015). Thus, the measured effects of engineered mutations in recombinant human Hb (Jessen et al., 1991; Weber et al., 1993) may not perfectly recapitulate the effects of the same mutational changes in the Hbs of other species, especially in taxa as divergent as birds and mammals (human Hb and bar-headed goose HbA differ at 89 of 287 sites in each αβ half-molecule). In light of these considerations, we performed a set of thermodynamic (equilibrium) and kinetic experiments to identify and characterize the allosteric mechanism responsible for the evolved increase in the O2 affinity of bar-headed goose HbA and its physiological regulation by anions and pH. Specifically, we measured O2 equilibrium curves and effects of allosteric cofactors in purified, native iso-Hbs of the bar-headed goose and the greylag goose and analyzed these curves to estimate allosteric parameters (i.e. L, KT and KR) describing Hb function according to the two-state MWC model (Monod et al., 1965). To provide a complete assessment of the factors underlying evolved differences in blood–O2 affinity, we examined the functional properties of the major HbA isoform as well as the minor HbD isoform of both species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood samples and Hb purification

Blood was sampled from a single, adult specimen each of the bar-headed goose [Anser indicus (Latham 1790)] and the greylag goose [Anser anser (Linnaeus 1758)] housed in outdoor pens (Galten, Aarhus, Denmark). Animals were gently restrained, and after exposing the brachial vein at the wing elbow joint, blood was collected using 5-ml heparinized syringes, with the needle pointing towards the tip of the wing. The whole procedure took less than 2 min. All animal procedures were approved by the Danish Law for Animal Experimentation (permit 2018-15-0201-01507).

We used an aliquot of blood from the same animal to genotype the adult-expressed globin genes (GenBank accession numbers: MH375701–MH375710). We isolated total RNA using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). We amplified full-length cDNAs for the major adult-expressed globin genes using a OneStep RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) and then cloned RT-PCR products using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and sequenced at least five clones per gene (αA, αD, βA) to recover both alleles of each globin gene (Natarajan et al., 2016, 2015).

Red blood cells (RBCs) were separated from plasma by centrifugation (3000 g, 15 min), washed in 0.9% NaCl and lysed on ice (30 min) by adding a 4-fold volume of ice-cold 10 mmol l−1 Hepes, pH 7.4, 0.5 mmol l−1 EDTA. The resulting hemolysate was centrifuged (12,000 g, 20 min) and the supernatant was loaded on a PD-10 5-ml desalting column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Town, State, Country) equilibrated with 10 mmol l−1 Hepes, pH 7.4, 0.5 mmol l−1 EDTA. Prior to loading samples, NaCl was added (to 0.2 mol l−1 final concentration) to facilitate removal of endogenous organic phosphates (stripping). Avian Hb isoforms HbA and HbD were then separated by anion exchange chromatography on a HiTrap Q HP 5-ml column connected to a Äkta Pure Chromatography System (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated with 10 mmol l−1 Tris-HCl pH 8.6, 0.5 mmol l−1 EDTA and eluted with a linear gradient of 0–250 mmol l−1 NaCl, at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. Eluate absorbance was monitored at 415 and 280 nm. This protocol also removed residual endogenous phosphates (Bonaventura et al., 1999; Rollema and Bauer, 1979). The purity of HbA and HbD isoforms was verified by isoelectric focusing on precast polyacrylamide gels (pH range 3–9) using the PhastSystem (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Purified HbA and HbD were then desalted by dialysis (Slide-A-Lyzer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) against 10 mmol l−1 Hepes, pH 7.6, 0.5 mmol l−1 EDTA, concentrated by ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Devices, Millipore, Town, State, Country) to a final heme concentration of >1 mmol l−1 and stored in aliquots at −80°C. Heme concentration (oxy derivative) was determined by absorption spectra (400–700 nm), and lack of heme oxidation was verified by the relative intensities of absorbance peaks at 575 and 541 nm of the oxy form (Van Assendelft and Zijlstra, 1975).

O2 equilibrium curves

Determination of P50 and cooperativity

Purified HbA and HbD (0.3 mmol l−1 heme) were dissolved in 0.1 mol l−1 Hepes, pH 7.4, in the absence (stripped) and presence of the allosteric effectors KCl (0.1 mol l−1) and inositol hexaphosphate (IHP, 0.15 mmol l−1) added separately or in combination. IHP is a chemical analog of the avian RBC organic phosphate inositol pentaphosphate (Johnson and Tate, 1969; Rollema and Bauer, 1979). O2 equilibria were measured in duplicate at 37°C in 5-µl samples using a thin-layer modified diffusion chamber described in detail elsewhere (Damsgaard et al., 2013; Janecka et al., 2015; Tufts et al., 2015; Weber, 1981, 1992; Weber et al., 1993). Absorbance at 436 nm was recorded to derive the fractional O2 saturation after stepwise equilibration with humidified gas mixtures (ultrapure N2 and O2 or air) of known O2 tension (PO2, torr). Absolute absorption data were sampled at a rate of 1 Hz, and PO2 values were entered into the data series using in-house designed software (Spektrosampler, K. Beedholm, Aarhus University, Denmark). Using the same program, saturation values were determined on the fly from relative absorbance and the nominally set PO2 values. An assumption was made that any drift in recorded absorption values was linear over the recording interval. For each Hb isoform and buffer condition, P50 and n50 (O2 tension and Hill cooperativity coefficient at half-saturation, respectively) were derived (mean±s.e.) by non-linear fitting of four to six saturation data points (O2 saturation range ∼0.2–0.8) using GraphPad Prism 6.01 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were fitted (r2>0.99) according to the sigmoidal Hill's equation Y=PO2n50/(P50n50+PO2n50), where Y is the fractional saturation. The allosteric binding of IHP to each Hb (0.3 mmol l−1 heme) was analyzed from plots of P50 versus IHP concentration (range 0–0.75 mmol l−1). For HbD, the IHP equilibrium dissociation constant (corresponding to the IHP concentration eliciting half of the maximal P50) was derived from non-linear fitting to a sigmoidal Hill's equation (r2>0.97 and r2>0.99 for the bar-headed goose and greylag goose HbD, respectively). The Bohr effect was measured under identical buffer conditions as described above, in the absence and presence of IHP, and in the pH range 6.7–7.8 for HbA and 6.7–7.4 for HbD. In these pH ranges, the Bohr factor (Φ=ΔlogP50/ΔpH) was constant under all conditions (r2>0.99).

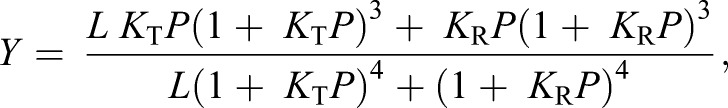

Determination of MWC allosteric parameters

To perform a detailed analysis of the allosteric regulation of O2 binding in HbA and HbD in terms of the two-state MWC model (Monod et al., 1965), it is necessary to cover a broad range of fractional saturations, including values approaching zero (<5%) and full (>95%) O2 saturation. To this end, we performed five to nine separate experiments as described above in the absence (stripped) and presence of saturating IHP concentration (0.75 mmol l−1), each experiment covering partially overlapping saturations. Data from all experiments were collectively analyzed by non-linear curve fitting using the MWC allosteric model (Monod et al., 1965). This model assumes the presence of an equilibrium between a low-affinity T state and a high-affinity R state, with KT and KR (torr−1) as O2 association equilibrium constants, respectively, and with the equilibrium constant L describing the [T]/[R] ratio in the absence of O2 (or any other heme ligand). Following a previous study (Weber et al., 1993), the allosteric parameters KT, KR and L were thus derived under each buffer condition by fitting (r2>0.99) the saturation function (Eqn 1) to the data:

|

(1) |

where P is the PO2. Saturation data were corrected by extrapolation for possible incomplete saturation with pure O2 or desaturation with pure N2, as described previously (Fago et al., 1997).

Stopped-flow kinetic measurements of O2 dissociation rates

O2 dissociation rates (koff, s−1) of HbA and HbD were measured by stopped-flow using an OLIS RSM 1000 UV/Vis rapid-scanning spectrophotometer (OLIS, Bogart, GA, USA) equipped with OLIS data collection software, as described previously (Helbo and Fago, 2012). In these experiments, one syringe of the stopped-flow contained 10 µmol l−1 oxy Hb in 200 mmol l−1 Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, in the absence (stripped) and presence of 10 µmol l−1 IHP alone and with 6.6 mmol l−1 KCl (using the same heme:KCl ratio as in equilibrium experiments). The other syringe contained 40 mmol l−1 sodium dithionite freshly prepared in deoxygenated buffer. The content of the two syringes was rapidly mixed at a 1:1 ratio at 37°C by stopped-flow and the O2 dissociation reaction (in which dithionite acts as an O2 scavenger) was followed by monitoring absorbance at 431 nm (peak of deoxy Hb). The reaction was completed within 0.15 s. Traces were best fitted (r2>0.99) by a monoexponential function using GraphPad Prism 6.01, yielding the O2 dissociation rate under each buffer condition. Rates are presented as means±s.d. from eight to nine and four to five separate experiments for HbA and HbD, respectively.

Gel filtration experiments

Apparent molecular weights of oxy and deoxy HbA and HbD were determined by gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex 75 10/300 GL column connected to an Äkta Pure Chromatography System (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and equilibrated with 50 mmol l−1 Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 mol l−1 NaCl, 0.5 mmol l−1 EDTA (elution buffer). Hb was loaded at a concentration of 0.3 mmol l−1 heme. The flow rate was 0.5 ml min−1 and absorbance of the eluate was monitored at 280 and 414 nm. In experiments with deoxy Hb, elution buffer was bubbled with N2 for at least 2 h before chromatographic runs and contained 0.3 mg ml−1 sodium dithionite, to remove possible residual oxygen (Fago and Weber, 1995; Storz et al., 2015; Weber et al., 2013). The effect of IHP on the molecular weight of the Hb was assessed by adding IHP (0.75 mmol l−1) to the elution buffer. Samples (0.3 mmol l−1 heme) of adult human Hb (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), Scapharca inaequivalvis HbI (kindly provided by Prof. E. Chiancone, University La Sapienza, Rome, Italy) and horse myoglobin (Sigma-Aldrich) were loaded to estimate elution times corresponding to tetrameric, dimeric and monomeric globin structures, respectively. As tetrameric human Hb tends to dissociate into dimers in gel filtration experiments, where it displays a lower apparent molecular weight (Ackers, 1964; Chiancone, 1968), these chromatographic experiments provide estimates of the type of quaternary assembly but not strictly of molecular weights (Fago et al., 2018; Kumar et al., 2017).

RESULTS

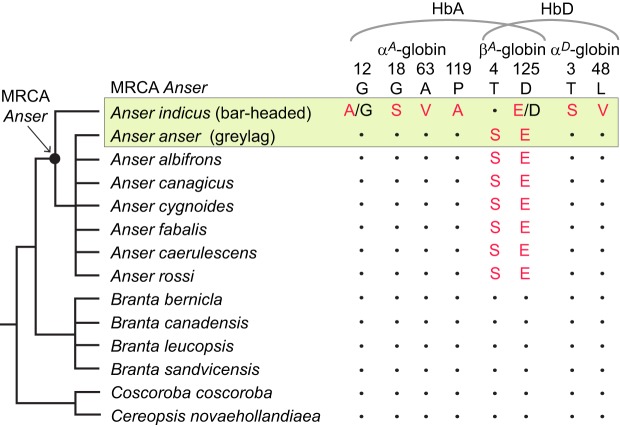

Cloning and sequencing of the adult-expressed globin genes from the bar-headed goose and greylag goose specimens confirmed previously documented amino acid substitutions that distinguish the HbA and HbD isoforms of the two species (Hiebl et al., 1987; McCracken et al., 2010; Oberthür et al., 1982) (Fig. 1). An alignment of orthologous sequences from 12 additional waterfowl species in the subfamily Anserinae revealed that all amino acid replacements in the αA- and αD-globin genes were specific to the bar-headed goose lineage. By contrast, the βA-globin replacements occurred in the common ancestor of greylag goose and all other lowland Anser species after divergence from the bar-headed goose (Fig. 1) (Natarajan et al., 2018). In addition to the six fixed differences in the three adult-expressed globin genes of bar-headed and greylag goose (four affecting HbA and two affecting HbD), the bar-headed goose specimen was heterozygous at two sites, αA12(Gly/Ala) and βA125(Asp/Glu) (Fig. 1). The allelic polymorphism at αA12 has been documented previously (McCracken et al., 2010). Available sequence data from bar-headed geese (Hiebl et al., 1987; McCracken et al., 2010; Oberthür et al., 1982) indicate that αA12Ala and βA125Glu represent low-frequency amino acid variants. Because the HbD isoforms of the bar-headed goose and the greylag goose have not been examined previously, it is noteworthy that αD-globin orthologs of the two species are distinguished by replacements at αD3(Thr→Ser) and αD48(Leu→Val) (Fig. 1). A sequence alignment of αA and αD from both species is shown in Fig. S1.

Fig. 1.

Amino acid replacements at eight sites that distinguish the HbA and HbD isoforms of the high-flying bar-headed goose (Anser indicus) and the strictly lowland greylag goose (Anser anser). Amino acid residues at the same sites are shown for 12 other lowland waterfowl species in the subfamily Anserinae and the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of the genus Anser (see Natarajan et al., 2018). Given the known phylogenetic relationships of these 12 waterfowl species, the multiple alignment clearly indicates that all amino acid replacements in αA- and αD-globin were specific to the bar-headed goose lineage, whereas the βA-globin replacements occurred in the common ancestor of greylag goose and all other lowland Anser species after divergence from the bar-headed goose. In addition to the six fixed differences in the three adult-expressed globin genes (four affecting HbA and two affecting HbD), bar-headed geese harbor low-frequency allelic polymorphisms at two sites, αA12(Gly/Ala) and βA125(Asp/Glu) (Hiebl et al., 1987; McCracken et al., 2010; Oberthür et al., 1982).

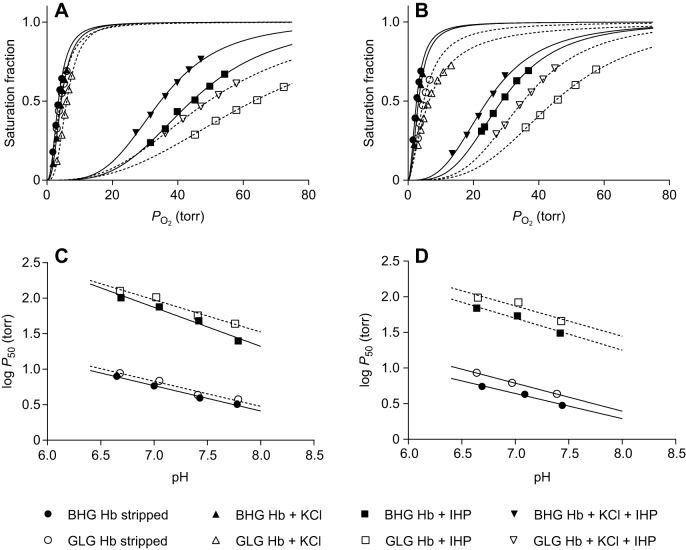

We purified native HbA and HbD isoforms from bar-headed goose and greylag goose hemolysates by anion exchange chromatography (Fig. S2). The HbA:HbD ratios estimated from the chromatographic profiles were ∼86:14 in the bar-headed goose and ∼90:10 in the greylag goose, consistent with data from other waterfowl taxa (Grispo et al., 2012; Natarajan et al., 2015; Opazo et al., 2015). O2 equilibrium curves of purified bar-headed goose HbA and HbD were left-shifted relatively to the respective Hbs of greylag goose (Fig. 2A) and showed consistently lower P50 values under all effector conditions examined (Table S1). Specifically, in the presence of IHP and KCl, the P50 values of bar-headed goose HbA and HbD were reduced 30% and 31%, respectively, relative to those of the corresponding greylag goose isoHbs. O2 binding was cooperative in all cases (n50=1.51–3.67; Table S1), reflecting a normal allosteric T–R shift upon oxygenation, with no evidence of super-cooperativity (Hill coefficients >4) described for some avian Hbs (Riggs, 1998). Under physiologically relevant conditions resembling those in the RBCs, i.e. in the presence of IHP and KCl, the bar-headed goose HbA had a much lower P50 (34.71 torr) than that (49.37 torr) of the greylag goose (Table S1). These P50 values are highly consistent with those reported for blood (Petschow et al., 1977). Stripped (anion-free) bar-headed goose HbA also had a slightly lower P50 than greylag goose HbA (3.72 and 4.24 torr, respectively; Table S1). Together, these data indicate that the difference in intrinsic O2 affinities (i.e. in the absence of allosteric anionic cofactors) between the HbA isoforms of the two species is greatly amplified in the presence of the physiological cofactor IHP, which had strong effects on HbA and HbD oxygenation (Fig. 2A,B; Table S1). The minor HbD had a consistently higher O2 affinity than HbA in each of the two species (Table S1).

Fig. 2.

O2 equilibrium curves and allosteric effects of anions and pH of bar-headed goose and greylag goose HbA and HbD. Representative O2 equilibrium curves (A,B) and Bohr effect (C,D) of purified HbA (A,C) and HbD (B,D) from the bar-headed goose (BHG, closed symbols) and the greylag goose (GLG, open symbols). Data were obtained at a heme concentration of 0.3 mmol l−1, 37°C, in 0.1 mol l−1 Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, in the absence (stripped) and presence of the allosteric effectors KCl (0.1 mol l−1) and inositol hexaphosphate (IHP, 0.15 mmol l−1) added separately or in combination, as indicated. Lines indicate fitting of the data according to Hill's sigmoidal equation (A,B) to derive O2 affinity (P50, torr) and cooperativity (n50) parameters, and to linear regression (C,D) to derive the Bohr factor (slope of the plot). Parameters from these experiments are listed in Table S1.

In both species, the Bohr effect of the two Hb isoforms was highly similar and was slightly enhanced by IHP (Fig. 2C,D; Table S1), as expected from anion-induced increase in Bohr proton binding. The Bohr factors were in good agreement with those reported earlier for native HbA of the two species (Rollema and Bauer, 1979) and for the recombinant human Hb wild type and αA119Pro→Ala mutant (Weber et al., 1993).

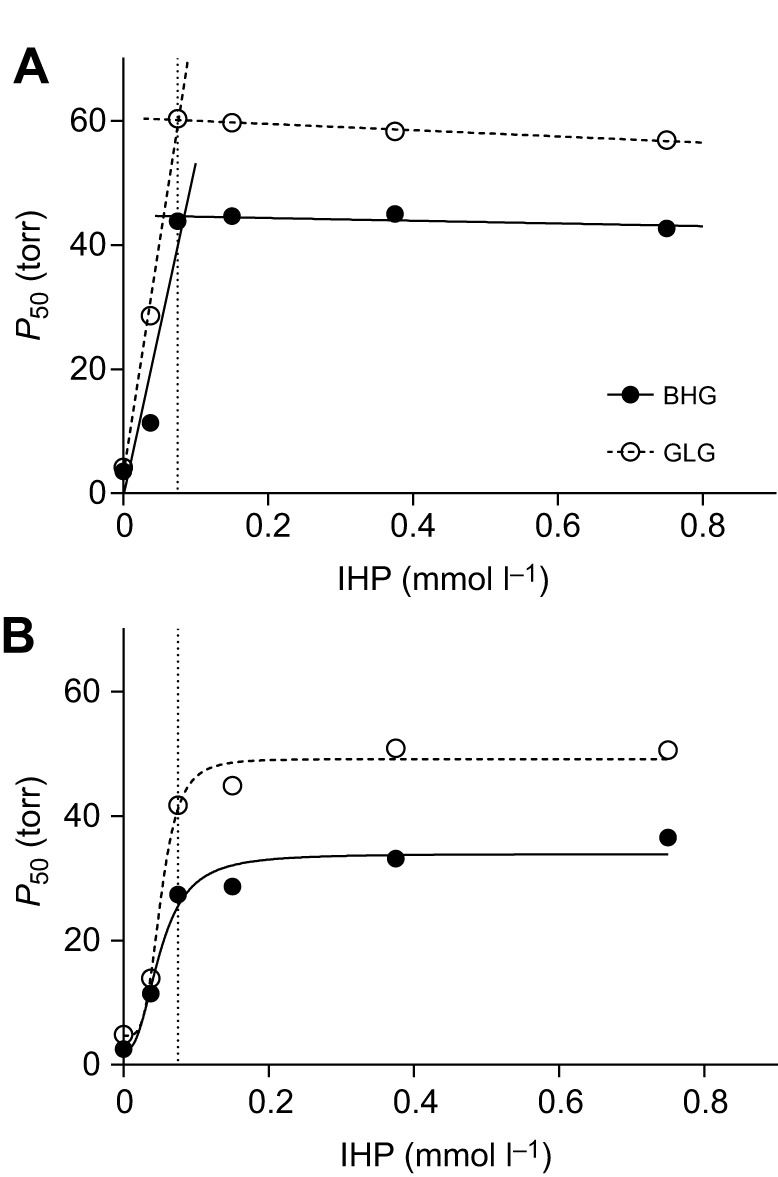

For both Hb isoforms, the anion IHP was a more potent allosteric effector than chloride, as it induced a larger right-hand shift in the O2 equilibrium curve (Fig. 2A,B). Moreover, O2 equilibrium curves were less right-shifted with KCl and IHP than with IHP alone (Fig. 2), indicating that these anions compete for binding sites on the Hb molecule. For the HbA and HbD isoforms of both species, we quantified the allosteric effect of IHP by measuring O2 equilibrium curves in the presence of increasing IHP concentrations (Fig. 3). These experiments revealed that IHP binding to the HbA of both species was essentially stoichiometric, as full saturation was achieved at a 1:1 molar ratio of IHP to Hb tetramer (Fig. 3A). This finding indicates that at an equimolar ratio of protein to effector, there is essentially no free IHP, reflecting a very high affinity for this effector (i.e. very low equilibrium dissociation constant <10−8 mol l−1), fully consistent with a previous study (Rollema and Bauer, 1979). The HbD isoforms of both species also bound IHP with high affinity (albeit lower than for HbA), with estimated values (means±s.e.) of equilibrium dissociation constants of 5.0±0.1×10−5 mol l−1 (bar-headed goose HbD) and 5.2±0.5×10−5 mol l−1 (greylag goose HbD) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of IHP on O2 affinity (P50, torr) of HbA and HbD of bar-headed goose (BHG, closed symbols) and greylag goose (GLG, open symbols). (A) Data for HbA followed a 1:1 stoichiometric binding of IHP to HbA (described by straight lines intersecting at 1:1 stoichiometry), whereby the affinity (equilibrium dissociation constant <10−8 mol l−1) cannot be estimated. (B) Data for HbD were best fitted according to sigmoidal equations (lines), yielding the Hb–IHP binding affinity as the IHP concentration at half-saturation. In both panels, the 1:1 tetrameric Hb to IHP ratio is indicated by a vertical dotted line. Data were obtained at a heme concentration of 0.3 mmol l−1 at 37°C, in 0.1 mol l−1 Hepes buffer, pH 7.4.

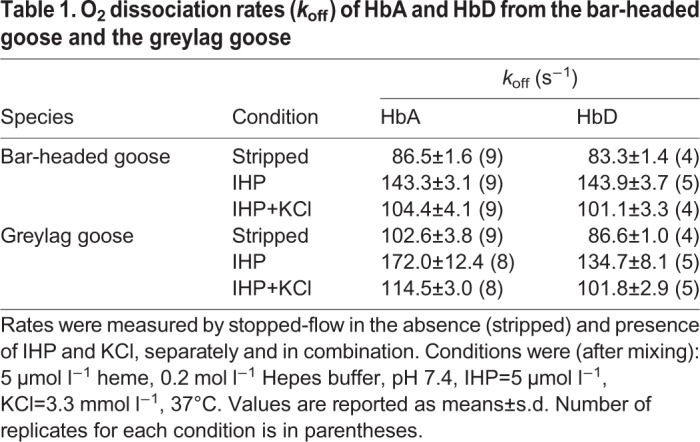

The O2 dissociation rate of oxy Hb was in all cases higher in the presence of IHP (Table 1). HbA from bar-headed goose showed lower O2 dissociation rates than greylag goose HbA under all conditions (Table 1), indicating that the amino acid substitutions that distinguish this isoHb in the two species alter the dissociation pathway of heme-bound O2. Bar-headed goose HbA and HbD dissociated O2 at nearly identical rates under the same conditions, whereas greylag goose HbA dissociated O2 slightly faster than HbD (Table 1). The fact that kinetic traces were best fitted by monoexponential functions further indicated that α and β hemes dissociated O2 at similar rates.

Table 1.

O2 dissociation rates (koff) of HbA and HbD from the bar-headed goose and the greylag goose

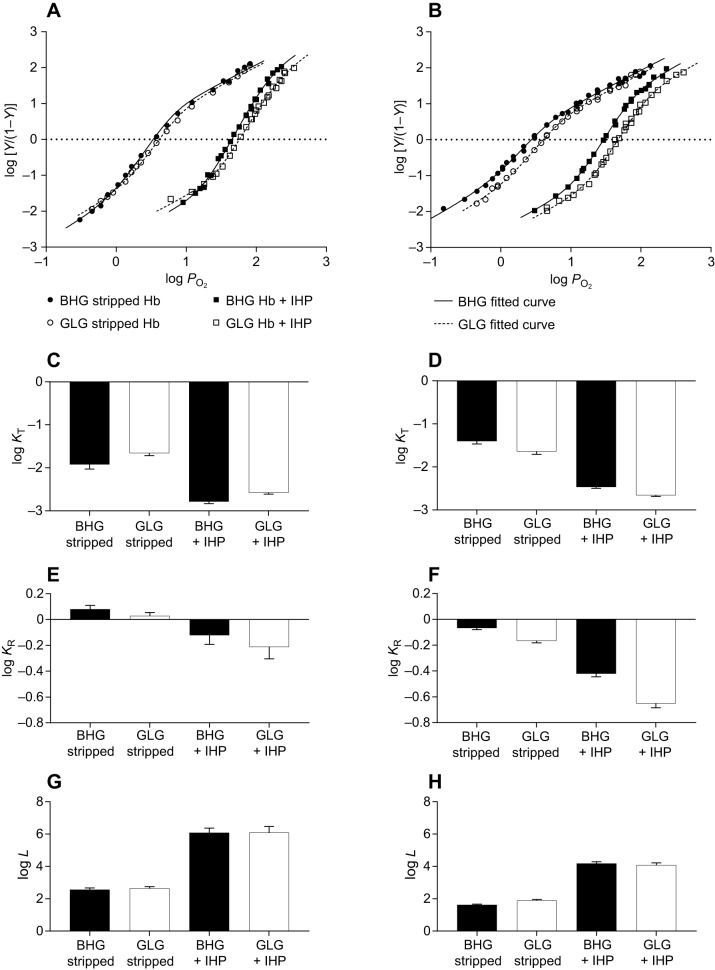

Having established that both HbA and HbD had higher O2 affinity in the bar-headed goose than in the greylag goose, especially in the presence of IHP (Table S1; Figs 2 and 3), we then examined the origin of this functional difference in terms of the two-state MWC allosteric model (Monod et al., 1965). To this end, we measured O2 equilibrium curves in the absence and presence of saturating IHP to cover a wide span of O2 saturations between zero and full saturation, and we fitted the data according to the MWC model (Eqn 1; Fig. 4). The derived allosteric MWC parameters (Table S2) included the O2 association equilibrium constants of the T and R states (KT and KR, respectively, torr−1) and the allosteric constant L, the [T]/[R] ratio in the absence of ligand. When comparing HbA of bar-headed goose and greylag goose, KR was consistently higher in the bar-headed goose (Fig. 4E) by approximately 12% and 26% in the absence and presence of IHP, respectively (Table S2). In addition, KT of the bar-headed goose HbA was consistently lower (Fig. 4C), whereas the allosteric constant L was the same (Fig. 4G). The minor isoform HbD of the bar-headed goose had higher KT and KR than HbD of the greylag goose (Fig. 4D,F), but highly similar L (Fig. 4H). For both HbA and HbD of each species, the IHP strongly decreased both the T-state O2 association equilibrium constant, KT (Fig. 4C,D), and the R-state O2 association constant, KR (Fig. 4E,F), while also increasing L (Fig. 4G,H). These findings indicate that IHP binds preferentially to the T state, thereby decreasing its O2 affinity and shifting the T–R equilibrium of the deoxy Hb towards the T state (increasing L), but that it also affects the R state. Comparison of MWC parameters for HbD with those for HbA (Table S2; Fig. 4) shows lower KR (Fig. 4E,F) but higher KT (Fig. 4C,D) and lower L (Fig. 4G,H) in the latter isoform. Higher KT and lower L explain the higher overall O2 affinity of HbD compared with HbA in terms of P50 (Table S1).

Fig. 4.

O2 equilibrium curves and fitting of allosteric MWC parameters of bar-headed goose and greylag goose HbA and HbD. (A,B) O2 equilibrium curves of purified HbA (A) and HbD (B) from the bar-headed goose (BHG, closed symbols) and greylag goose (GLG, open symbols) covering a wide range of saturations (approaching 0% and 100%) to derive allosteric parameters describing Hb function according the MWC model. Measurements from five to nine separate experiments were carried out at a heme concentration of 0.3 mmol l−1 at 37°C, in 0.1 mol l−1 Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, in the absence (stripped) and presence of IHP (0.15 mmol l−1). The curves show fitting of all measured data under a given condition according to the saturation function (Eqn 1) describing the MWC model (parameters of this analysis are reported in Table S3). (C–H) Derived parameters (means±s.e.) logKT (C,D) and logKR (E,F), the O2 association equilibrium constants of the T and R states, respectively, and L (G,H), the allosteric equilibrium constant describing the [T]/[R] ratio in the absence of O2. Closed bars, bar-headed goose (BHG); open bars, greylag goose (GLG).

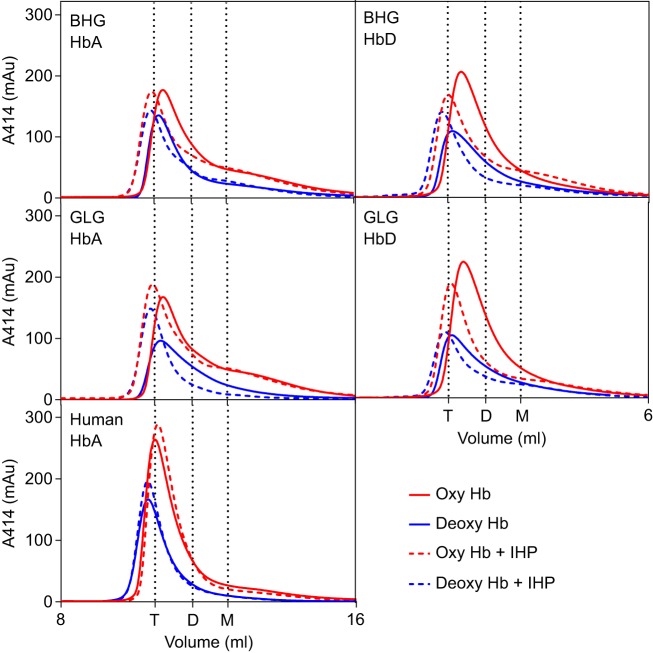

To determine whether IHP may affect O2 binding properties via changes in the structural assembly of the Hb, we examined the apparent molecular weight of oxy and deoxy HbA and HbD of both species by gel filtration in the absence and presence of IHP. Although HbA and HbD were mainly present in the tetrameric form under all conditions (Fig. 5), an extended ‘tail’ observed in the elution profile in the absence of IHP indicated the presence of a small fraction of dissociation products (caused by protein dilution during column migration) that almost disappeared in deoxygenated conditions and in the presence of IHP. For comparison, human Hb maintained the same elution profile regardless of IHP (Fig. 5). Taken together, these results indicate that HbA and HbD from the bar-headed and greylag goose may form less-tight subunit interactions than human Hb, and that IHP binding stabilizes the tetrameric assembly considerably.

Fig. 5.

Gel filtration elution profiles of HbA and HbD from the bar-headed goose (BHG) and the greylag goose (GLG) and of human adult HbA in the absence (continuous line) and presence of IHP (dashed line), under oxygenated (red) and deoxygenated (blue) conditions. Dotted vertical lines indicate the elution peaks of tetrameric Hb (T), dimeric Hb (D) and monomeric Mb (M) globins.

DISCUSSION

A key finding of this study is that the evolved increase in O2 affinity (decrease in P50) of bar-headed goose HbA compared with greylag goose HbA is attributable to an increased O2 association equilibrium of the R state (higher KR) (Fig. 4E) and not from a less stable T state, as earlier proposed (Perutz, 1983). In fact, the HbA of the two species have identical L values under identical conditions (Fig. 4G), which reflects a similar stability of the T state relative to the R state. The higher R-state O2 association constant of the bar-headed goose HbA derives, at least in part, from a slower O2 dissociation of the fully saturated protein compared with the greylag goose HbA (Table 1). This property may reflect the slightly different subunit orientation found in the crystal structure of the bar-headed goose oxy HbA compared with human Hb, although the α and β heme pockets appeared very similar (Zhang et al., 1996). The higher R-state O2 association constant of the bar-headed goose HbA has important physiological implications. Because Hb is in the R state in the lungs, where the O2 tension is high, the higher KR of bar-headed goose HbA would enhance O2 loading in the upper part of the blood O2 equilibrium curve, well after the T–R transition has taken place at intermediate saturations. Furthermore, the T-state HbA has a lower O2 association equilibrium constant (lower KT) in the bar-headed goose than in the greylag goose (Fig. 4C), a property that would favor O2 unloading at the low O2 tensions prevailing in working muscles. However, this decrease in KT is not large enough to offset the concomitant increase in KR, and the resulting overall O2 affinity (in terms of P50) is therefore higher in the bar-headed goose HbA compared with the greylag goose HbA (Fig. 2A). Taken together, our results show how opposite functional effects on each of the two quaternary states of the major HbA isoform may act together to improve O2 transport (increase the difference between loading and unloading) in the bar-headed goose at high altitudes. In contrast to our functional analysis, introduction of the αA119Pro→Ala mutation into recombinant human Hb had the effect of increasing the T-state O2 association constant and decreasing L, while leaving the R-state O2 association constant unaffected (Weber et al., 1993) (Table S2). These changes, although still consistent with a decrease in P50, would have the unwanted in vivo consequence of disfavoring unloading of O2 to tissues, while leaving O2 loading at the lungs almost unaffected.

Another factor that increases arterial blood O2 saturation in the bar-headed goose is the respiratory alkalosis initially experienced at low inspired PO2 (Black and Tenney, 1980; Lague et al., 2016), which would increase overall O2 affinity via the Bohr effect (Table S1). However, given that bar-headed and greylag goose Hbs display highly similar Bohr factors, the increment in blood O2 saturation in the two goose species would be similar for a given increment in blood pH. Moreover, studies on acid–base regulation in bar-headed and greylag geese reveal the onset of a metabolic acidosis at low inspired PO2 (Scott and Milsom, 2007; Lague et al., 2016).

Our analysis in terms of the MWC model shows that IHP causes marked reductions in the O2 association equilibrium constant of the T (Fig. 4C,D) and R states (Fig. 4E,F) and a strong shift of the T–R state equilibrium towards the T state, as reflected by increased L (Fig. 4G,H). These results indicate that IHP binding to HbA and HbD induces conformational changes that affect heme–O2 binding within each of the two quaternary states. These functional effects of IHP can be ascribed in part to enhanced heme–O2 dissociation rates (Table 1). Binding of IHP to the HbA of both species was particularly strong and followed stoichiometric binding (Fig. 3A), supporting earlier reports of extremely high affinities for inositol pentaphosphate (IPP) (Rollema and Bauer, 1979). By virtue of the strong allosteric effect of IPP on HbA oxygenation (Rollema and Bauer, 1979), altitude-related change in IPP levels in the RBCs will effectively cause marked left or right shifts in the blood O2 equilibrium curves. It should be borne in mind that the bar-headed goose is exposed to high altitude only during seasonal migrations, while spending long periods of the year at low to moderate altitudes (Bishop et al., 2015; Hawkes et al., 2013, 2011; Scott et al., 2015). Changes in RBC levels of organic phosphates result in immediate and reversible adjustments in blood O2 transport properties to altitude variations, as found in species in which the levels of organic phosphates change during hypoxia (Fago, 2017; Weber, 2007; Weber and Fago, 2004). Whether IPP levels of RBCs change significantly upon altitude exposure in the bar-headed goose remains to be determined. Although some studies indicate that IPP levels in bird RBCs remain constant (Jaeger and McGrath, 1974; Lutz, 1980), others have reported slightly increased arterial O2 content in bar-headed geese reared at high altitudes (Lague et al., 2016), which suggests decreased IPP content in RBCs.

The structure of the IPP binding site in the bar-headed goose provides a basis for these functional effects. The IPP binding site corresponds to a constellation of positively charged amino acid residues located in the cleft between the β subunits (Arnone and Perutz, 1974; Grispo et al., 2012; Riccio et al., 2001; Tamburrini et al., 2000). These positive residues are neutralized when bound to negatively charged IPP or IHP. Our data on stripped HbA and HbD (Fig. 4) indicate that, in the absence of IHP, extensive electrostatic repulsions in this cluster of charged residues effectively destabilize the T state and shift the T–R equilibrium towards the R state, as reflected by a low L (Fig. 4G,H; Table S2). This may explain why the low-salt crystal structure of bar-headed goose deoxy HbA is essentially in the R state (Liang et al., 2001). When IHP neutralizes this positively charged patch, the T–R equilibrium shifts towards the low-affinity T state (as shown by the large increase in L) (Fig. 4G,H), and the O2 affinity consequently decreases (Fig. 2A,B). The view that an excess of positively charged residues located at specific protein clusters may effectively promote Hb T–R switches is not new and has been invoked earlier to explain other allosteric effects in vertebrate Hbs, such as chloride effects (Bonaventura et al., 1994), the Root effect (Mylvaganam et al., 1996), the reverse Bohr effect and high phosphate sensitivities (Fago et al., 1995). In addition, excess of positive charges at the IPP binding site cluster may explain the higher tendency to dissociate into dimers in geese Hbs compared with human Hb in gel filtration experiments, a tendency that is reversed by IHP (Fig. 5). The less defined patch of positively charged residues at the IPP binding site of HbD compared with HbA (Grispo et al., 2012) is also in agreement with the lower binding affinity of IHP to HbD (Fig. 3B).

The minor isoform HbD has an overall higher O2 affinity (i.e. lower P50) than HbA (Table S1), consistent with reports from previous studies of isoHb differentiation in birds (Grispo et al., 2012; Natarajan et al., 2016, 2015; Opazo et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2018). However, the MWC analysis revealed that HbD has a lower KR than HbA (Table S2; Fig. 4), and is therefore less suited to enhance O2 loading at the lungs at high altitude. Moreover, HbD is equally as sensitive to pH changes as HbA (Fig. 2C,D; Table S1) but it is less sensitive than HbA to IHP (Fig. 3), and by inference less responsive to potential hypoxia-induced changes in IPP levels in RBCs. Thus, although HbA and HbD of the bar-headed goose both evolved similar increases in O2 affinity relative to the corresponding isoHbs of the greylag goose, the allosteric properties of HbA appear better suited to high-altitude O2 transport. Because the two isoHbs share the same βA chains, the observed differences in O2 affinity and effector sensitivity must be attributable to the net effect of 61 amino acid substitutions that distinguish the αA- and αD-globin paralogs (Fig. S1).

Conclusions

Our experimental data confirm that the major isoform HbA of the bar-headed goose has a higher O2 affinity than that of the greylag goose, consistent with previous studies (Black and Tenney, 1980; Jessen et al., 1991; Petschow et al., 1977). For the first time, we document a quantitatively similar species difference in O2 affinity of the minor HbD isoform. Most importantly, the experimental data shed light on the functional mechanism responsible for the evolved changes in bar-headed goose HbA and HbD.

Of the amino acid substitutions that distinguish HbA and HbD of the bar-headed goose from the corresponding Hb isoforms of the greylag goose, phylogenetic evidence clearly indicates that all αA and αD substitutions occurred in the bar-headed goose lineage, whereas all βA substitutions occurred in the common ancestor of all lowland Anser species (including A. anser) after diverging from the line of descent leading to the bar-headed goose (Natarajan et al., 2018) (Fig. 1). In the case of the major HbA isoform, site-directed mutagenesis experiments involving reconstructed ancestral Hbs demonstrated that the evolved increase in HbA O2 affinity of the bar-headed goose compared with the greylag goose (Fig. 2; Table S1) is mainly attributable to the net effect of the three αA substitutions that are specific to the bar-headed goose at αA sites 18, 63 and 119 (Fig. 1) (Natarajan et al., 2018). Because HbA and HbD share the same βA-chain subunit, it is equally clear that the evolved increase in HbD O2 affinity (Fig. 2; Table S1) is attributable to the independent or joint effects of the two amino acid replacements at αD sites 3 and 48 in the αD-globin of the bar-headed goose (Fig. 1). Thus, substitutions in the α-type chains of both isoHbs contribute to the increased overall blood–O2 affinity of the high-flying bar-headed goose relative to the lowland greylag goose.

Our combination of equilibrium and kinetic measurements provide novel insights into the functional mechanism responsible for the evolved increase in Hb–O2 affinity in the bar-headed goose. Contrary to Perutz's hypothesis (Perutz, 1983), the increased O2 affinity of bar-headed goose HbA is not attributable to an evolved change in the equilibrium constant between the T and R conformations of the protein, L, as HbA of bar-headed goose and greylag goose are identical in this regard (Fig. 4G). Instead, in the presence of physiological anion concentrations, the increased HbA–O2 affinity of the bar-headed goose is primarily attributable to an increase in KR, the O2 association constant for Hb in the R state (Fig. 4E), thereby favoring loading at the lungs. This increase in KR overrides a concomitant decrease in KT, the O2 association constant for Hb in the T state (Fig. 4C), which favors O2 unloading to severely hypoxic tissues. The increased O2 affinity of bar-headed goose HbD is primarily attributable to combined increases in KR and KT, but not in L (Fig. 4D–H). The particularly strong allosteric effect of organic phosphates on the O2 affinity of HbA suggests a potential adaptive role for blood O2 transport during rapid changes in altitudes.

The elevated Hb–O2 affinity of the bar-headed goose is an iconic, textbook example of biochemical adaptation (Hochachka and Somero, 2002; Scott et al., 2015). The findings presented here provide us with a more complete understanding of the mechanistic basis of the evolved change in protein function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Elin E. Petersen (Aarhus University) for skilled technical assistance.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A.J., R.E.W., J.F.S., A.F.; Methodology: H.M., K.B., C.N., J.F.S., A.F.; Software: H.M., K.B.; Validation: H.M., K.B., C.N., J.F.S., A.F.; Formal analysis: A.J., H.M., C.B., C.N.; Investigation: A.J., C.B., C.N.; Resources: J.F.S., A.F.; Data curation: A.J., H.M., C.B., K.B., A.F.; Writing - original draft: A.J., J.F.S., A.F.; Writing - review & editing: A.J., K.B., C.N., R.E.W., J.F.S., A.F.; Visualization: A.J., C.N., J.F.S., A.F.; Supervision: R.E.W., J.F.S., A.F.; Project administration: J.F.S., A.F.; Funding acquisition: J.F.S., A.F.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (HL087216 to J.F.S.), the National Science Foundation (MCB- 1517636 and RII Track-2 FEC-1736249 to J.F.S.) and Natur og Univers, Det Frie Forskningsråd (4181-00094 to A.F.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Data availability

The Spektrosampler program (K. Beedholm, Aarhus University, Denmark) is available at: http://www.marinebioacoustics.com/sharing/spektrosampler.zip.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jeb.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jeb.185470.supplemental

References

- Ackers G. K. (1964). Molecular exclusion and restricted diffusion processes in molecular-sieve chromatography. Biochemistry 3, 723-730. 10.1021/bi00893a021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone A. and Perutz M. F. (1974). Structure of inositol hexaphosphate–human deoxyhaemoglobin complex. Nature 249, 34-36. 10.1038/249034a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop C. M., Spivey R. J., Hawkes L. A., Batbayar N., Chua B., Frappell P. B., Milsom W. K., Natsagdorj T., Newman S. H., Scott G. R. et al. (2015). The roller coaster flight strategy of bar-headed geese conserves energy during Himalayan migrations. Science 347, 250-254. 10.1126/science.1258732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black C. P. and Tenney S. M. (1980). Oxygen transport during progressive hypoxia in high-altitude and sea-level waterfowl. Respir. Physiol. 39, 217-239. 10.1016/0034-5687(80)90046-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaventura C., Arumugam M., Cashon R., Bonaventura J. and Moo-Penn W. F. (1994). Chloride masks effects of opposing positive charges in Hb A and Hb Hinsdale (β139 Asn→Lys) that can modulate cooperativity as well as oxygen affinity. J. Mol. Biol. 239, 561-568. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaventura C., Ferruzzi G., Tesh S. and Stevens R. D. (1999). Effects of S-nitrosation on oxygen binding by normal and sickle cell hemoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 24742-24748. 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiancone E. (1968). Dissociation of hemoglobin into subunits. II. Human oxyhemoglobin: gel filtration studies. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 1212-1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsgaard C., Storz J. F., Hoffmann F. G. and Fago A. (2013). Hemoglobin isoform differentiation and allosteric regulation of oxygen binding in the turtle, Trachemys scripta. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 305, R961-R967. 10.1152/ajpregu.00284.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fago A. (2017). Functional roles of globin proteins in hypoxia-tolerant ectothermic vertebrates. J. Appl. Physiol. 123, 926-934. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00104.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fago A. and Weber R. E. (1995). The hemoglobin system of the hagfish Myxine glutinosa: aggregation state and functional properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1249, 109-115. 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00031-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fago A., Carratore V., di Prisco G., Feuerlein R. J., Sottrup-Jensen L. and Weber R. E. (1995). The cathodic hemoglobin of Anguilla anguilla. Amino acid sequence and oxygen equilibria of a reverse Bohr effect hemoglobin with high oxygen affinity and high phosphate sensitivity. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 18897-18902. 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fago A., Bendixen E., Malte H. and Weber R. E. (1997). The anodic hemoglobin of Anguilla anguilla. Molecular basis for allosteric effects in a Root-effect hemoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 15628-15635. 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fago A., Rohlfing K., Petersen E. E., Jendroszek A. and Burmester T. (2018). Functional diversification of sea lamprey globins in evolution and development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1866, 283-291. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2017.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galen S. C., Natarajan C., Moriyama H., Weber R. E., Fago A., Benham P. M., Chavez A. N., Cheviron Z. A., Storz J. F. and Witt C. C. (2015). Contribution of a mutational hot spot to hemoglobin adaptation in high-altitude Andean house wrens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 13958-13963. 10.1073/pnas.1507300112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grispo M. T., Natarajan C., Projecto-Garcia J., Moriyama H., Weber R. E. and Storz J. F. (2012). Gene duplication and the evolution of hemoglobin isoform differentiation in birds. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 37647-37658. 10.1074/jbc.M112.375600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes L. A., Balachandran S., Batbayar N., Butler P. J., Frappell P. B., Milsom W. K., Tseveenmyadag N., Newman S. H., Scott G. R., Sathiyaselvam P. et al. (2011). The trans-Himalayan flights of bar-headed geese (Anser indicus). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9516-9519. 10.1073/pnas.1017295108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes L. A., Balachandran S., Batbayar N., Butler P. J., Chua B., Douglas D. C., Frappell P. B., Hou Y., Milsom W. K., Newman S. H. et al. (2013). The paradox of extreme high-altitude migration in bar-headed geese Anser indicus. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 280, 20122114 10.1098/rspb.2012.2114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbo S. and Fago A. (2012). Functional properties of myoglobins from five whale species with different diving capacities. J. Exp. Biol. 215, 3403-3410. 10.1242/jeb.073726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiebl I., Braunitzer G. and Schneeganss D. (1987). The primary structures of the major and minor hemoglobin-components of adult Andean goose (Chloephaga melanoptera, Anatidae): the mutation Leu→Ser in position 55 of the beta-chains. Biol. Chem. Hoppe Seyler 368, 1559-1569. 10.1515/bchm3.1987.368.2.1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka P. W. and Somero G. N. (2002). Biochemical Adaptation. Mechanism and Process in Physiological Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger J. J. and McGrath J. J. (1974). Hematologic and biochemical effects of simulated high altitude on the Japanese quail. J. Appl. Physiol. 37, 357-361. 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.3.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janecka J. E., Nielsen S. S. E., Andersen S. D., Hoffmann F. G., Weber R. E., Anderson T., Storz J. F. and Fago A. (2015). Genetically based low oxygen affinities of felid hemoglobins: lack of biochemical adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia in the snow leopard. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 2402-2409. 10.1242/jeb.125369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen T. H., Weber R. E., Fermi G., Tame J. and Braunitzer G. (1991). Adaptation of bird hemoglobins to high altitudes: demonstration of molecular mechanism by protein engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 6519-6522. 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L. F. and Tate M. E. (1969). Structure of “phytic acids”. Can. J. Chem. 47, 63-73. 10.1139/v69-008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Natarajan C., Moriyama H., Witt C. C., Weber R. E., Fago A. and Storz J. F. (2017). Stability-mediated epistasis restricts accessible mutational pathways in the functional evolution of avian hemoglobin. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1240-1251. 10.1093/molbev/msx085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lague S. L., Chua B., Farrell A. P., Wang Y. and Milsom W. K. (2016). Altitude matters: differences in cardiovascular and respiratory responses to hypoxia in bar-headed geese reared at high and low altitudes. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 1974-1984. 10.1242/jeb.132431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Hua Z., Liang X., Xu Q. and Lu G. (2001). The crystal structure of bar-headed goose hemoglobin in deoxy form: the allosteric mechanism of a hemoglobin species with high oxygen affinity. J. Mol. Biol. 313, 123-137. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz P. L. (1980). On the oxygen affinity of bird blood. Am. Zool. 20, 187-198. 10.1093/icb/20.1.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken K. G., Barger C. P. and Sorenson M. D. (2010). Phylogenetic and structural analysis of the HbA (αA/βA) and HbD (αD/βA) hemoglobin genes in two high-altitude waterfowl from the Himalayas and the Andes: bar-headed goose (Anser indicus) and Andean goose (Chloephaga melanoptera). Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 56, 649-658. 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meir J. U. and Milsom W. K. (2013). High thermal sensitivity of blood enhances oxygen delivery in the high-flying bar-headed goose. J. Exp. Biol. 216, 2172-2175. 10.1242/jeb.085282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monod J., Wyman J. and Changeux J.-P. (1965). On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. J. Mol. Biol. 12, 88-118. 10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80285-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mylvaganam S. E., Bonaventura C., Bonaventura J. and Getzoff E. D. (1996). Structural basis for the Root effect in haemoglobin. Nature Struct. Biol. 3, 275-283. 10.1038/nsb0396-275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan C., Inoguchi N., Weber R. E., Fago A., Moriyama H. and Storz J. F. (2013). Epistasis among adaptive mutations in deer mouse hemoglobin. Science 340, 1324-1327. 10.1126/science.1236862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan C., Projecto-Garcia J., Moriyama H., Weber R. E., Muñoz-Fuentes V., Green A. J., Kopuchian C., Tubaro P. L., Alza L., Bulgarella M. et al. (2015). Convergent evolution of hemoglobin function in high-altitude Andean waterfowl involves limited parallelism at the molecular sequence level. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005681 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan C., Hoffmann F. G., Weber R. E., Fago A., Witt C. C. and Storz J. F. (2016). Predictable convergence in hemoglobin function has unpredictable molecular underpinnings. Science 354, 336-339. 10.1126/science.aaf9070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan C., Jendroszek A., Kumar A., Weber R. E., Tame J. R. H., Fago A. and Storz J. F. (2018). Molecular basis of hemoglobin adaptation in the high-flying bar-headed goose. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007331 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberthür W., Braunitzer G. and Würdinger I. (1982). Hemoglobins, XLVII. Hemoglobins of the bar-headed goose (Anser indicus): primary structure and physiology of respiration, systematic and evolution. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol. Chem. 363, 581-590. 10.1515/bchm2.1982.363.1.581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opazo J. C., Hoffmann F. G., Natarajan C., Witt C. C., Berenbrink M. and Storz J. F. (2015). Gene turnover in the avian globin gene families and evolutionary changes in hemoglobin isoform expression. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 871-887. 10.1093/molbev/msu341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perutz M. F. (1983). Species adaptation in a protein molecule. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1, 1-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petschow D., Wurdinger I., Baumann R., Duhm J., Braunitzer G. and Bauer C. (1977). Causes of high blood O2 affinity of animals living at high altitude. J. Appl. Physiol. 42, 139-143. 10.1152/jappl.1977.42.2.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Projecto-Garcia J., Natarajan C., Moriyama H., Weber R. E., Fago A., Cheviron Z. A., Dudley R., McGuire J. A., Witt C. C. and Storz J. F. (2013). Repeated elevational transitions in hemoglobin function during the evolution of Andean hummingbirds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 20669-20674. 10.1073/pnas.1315456110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio A., Tamburrini M., Giardina B. and di Prisco G. (2001). Molecular dynamics analysis of a second phosphate site in the hemoglobins of the seabird, South Polar skua. Is there a site-site migratory mechanism along the central cavity? Biophys. J. 81, 1938-1946. 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75845-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs A. F. (1998). Self-association, cooperativity and supercooperativity of oxygen binding by hemoglobins. J. Exp. Biol. 201, 1073-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H. S. and Bauer C. (1979). The interaction of inositol pentaphosphate with the hemoglobins of highland and lowland geese. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 12038-12043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott G. R. (2011). Elevated performance: the unique physiology of birds that fly at high altitudes. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 2455-2462. 10.1242/jeb.052548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott G. R. and Milsom W. K. (2006). Flying high: a theoretical analysis of the factors limiting exercise performance in birds at altitude. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 154, 284-301. 10.1016/j.resp.2006.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott G. R. and Milsom W. K. (2007). Control of breathing and adaptation to high altitude in the bar-headed goose. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 293, R379-R391. 10.1152/ajpregu.00161.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott G. R., Hawkes L. A., Frappell P. B., Butler P. J., Bishop C. M. and Milsom W. K. (2015). How bar-headed geese fly over the Himalayas. Physiology 30, 107-115. 10.1152/physiol.00050.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz J. F. (2016). Hemoglobin-oxygen affinity in high-altitude vertebrates: is there evidence for an adaptive trend? J. Exp. Biol. 219, 3190 10.1242/jeb.127134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz J. F. (2018). Compensatory mutations and epistasis for protein function. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 50, 18-25. 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz J. F., Natarajan C., Moriyama H., Hoffmann F. G., Wang T., Fago A., Malte H., Overgaard J. and Weber R. E. (2015). Oxygenation properties and isoform diversity of snake hemoglobins. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 309, R1178-R1191. 10.1152/ajpregu.00327.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburrini M., Riccio A., Romano M., Giardina B. and di Prisco G. (2000). Structural and functional analysis of the two haemoglobins of the Antarctic seabird Catharacta maccormicki. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 6089-6098. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01699.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufts D. M., Natarajan C., Revsbech I. G., Projecto-Garcia J., Hoffmann F. G., Weber R. E., Fago A., Moriyama H. and Storz J. F. (2015). Epistasis constrains mutational pathways of hemoglobin adaptation in high-altitude pikas. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 287-298. 10.1093/molbev/msu311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Assendelft O. W. and Zijlstra W. G. (1975). Extinction coefficients for use in equations for the spectrophotometric analysis of haemoglobin mixtures. Anal. Biochem. 69, 43-48. 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90563-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward S., Bishop C. M., Woakes A. J. and Butler P. J. (2002). Heart rate and the rate of oxygen consumption of flying and walking barnacle geese (Branta leucopsis) and bar-headed geese (Anser indicus). J. Exp. Biol. 205, 3347-3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber R. E. (1981). Cationic control of O2 affinity in lugworm erythrocruorin. Nature 292, 386-387. 10.1038/292386a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber R. E. (1992). Use of ionic and zwitterionic (Tris/BisTris and HEPES) buffers in studies on hemoglobin function. J. Appl. Physiol. 72, 1611-1615. 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.4.1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber R. E. (2007). High-altitude adaptations in vertebrate hemoglobins. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 158, 132-142. 10.1016/j.resp.2007.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber R. E. and Fago A. (2004). Functional adaptation and its molecular basis in vertebrate hemoglobins, neuroglobins and cytoglobins. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 144, 141-159. 10.1016/j.resp.2004.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber R. E., Jessen T. H., Malte H. and Tame J. (1993). Mutant hemoglobins (alpha 119-Ala and beta 55-Ser): functions related to high-altitude respiration in geese. J. Appl. Physiol. 75, 2646-2655. 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.6.2646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber R. E., Fago A., Malte H., Storz J. F. and Gorr T. A. (2013). Lack of conventional oxygen-linked proton and anion binding sites does not impair allosteric regulation of oxygen binding in dwarf caiman hemoglobin. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 305, R300-R312. 10.1152/ajpregu.00014.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Hua Z., Tame J. R. H., Lu G., Zhang R. and Gu X. (1996). The crystal structure of a high oxygen affinity species of haemoglobin (bar-headed goose haemoglobin in the oxy form). J. Mol. Biol. 255, 484-493. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Guan Y., Signore A. V., Natarajan C., DuBay S. G., Cheng Y., Han N., Song G., Qu Y., Moriyama H. et al. (2018). Divergent and parallel routes of biochemical adaptation in high-altitude passerine birds from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 1865 10.1073/pnas.1720487115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.