Abstract

Background and Objectives

Mobility limitation is common and has been linked to high energetic requirements of daily activities, including walking. The study objective was to determine whether two separate forms of exercise could reduce the energy cost of walking and secondary outcomes related to activity and participation domains among older adults with mobility limitation.

Research Design and Methods

Community-dwelling older adults with self-reported mobility limitation (n = 72) were randomized to 12 weeks of twice-weekly, group-based, instructor-led timing and coordination, aerobic walking, or stretching and relaxation (active control) programs. The primary outcome was the energy cost of walking (mL O2/kg/m), assessed by a 5-minute treadmill walking test (0.8 m/s). Secondary outcomes were fatigability, physical activity, endurance, physical function, and life-space. Baseline-adjusted ANCOVAs were used to determine mean differences between exercise and control groups at 12 and 24 weeks.

Results

Exercise session attendance was high: 86% for timing and coordination, 81% for aerobic walking, and 90% for stretching and relaxation. At 12 weeks, timing and coordination reduced the mean energy cost of walking by 15% versus stretching and relaxation (p = .008). Among those with high baseline cost, timing and coordination reduced mean energy cost by 20% versus stretching and relaxation (p = .055). Reductions were sustained at 24 weeks. Aerobic walking had no effect on the energy cost of walking at 12 or 24 weeks. At 12 weeks, there was a trend toward faster gait speed (by 0.1 m/s) in timing and coordination versus stretching and relaxation (p = .074). Fatigability, physical activity, endurance, physical function, and life-space did not change with timing and coordination or aerobic walking versus stretching and relaxation at 12 or 24 weeks.

Discussion and Implications

Twelve weeks of timing and coordination, but not aerobic walking, reduced the energy cost of walking among older adults with mobility limitation, particularly among those with high baseline energy cost; reductions in energy cost were sustained following training cessation. Timing and coordination also led to a trend toward faster gait speed.

Keywords: Energy cost of walking, Fatigability, Gait speed, Timing and coordination training, Elderly

Translational Significance

Mobility is fundamental to healthy aging, but mobility limitation is common and has been linked to a high energetic cost of walking. Older adults with mobility limitation assigned to 12 weeks of exercise that trained the timing and coordination of walking reduced their mean energy cost of walking by 15% compared with an active control group.

Background and Objectives

Mobility limitation, typically defined as difficulty walking one-quarter mile or climbing one flight of stairs (1), is reported by 30%–40% of older adults (2). Mobility limitation is a precursor to more severe mobility disability and increased dependence in daily activities (3), entry into nursing homes (4), and mortality (5). An emerging body of evidence supports the hypothesis that high energy requirements for daily activities, such as walking, play a central role in the development of mobility limitation among older adults (6–9).

The energy cost of walking measures how much physiological work the body must perform during walking. Most healthy individuals have a preferred walking speed that minimizes their energy cost of walking (10). The energy cost of walking rises progressively with aging and is especially high among older adults who report walking difficulty (6,11,12). In young adults, the energy cost of walking at preferred speed averages approximately 0.15 mL O2/kg/m (12), whereas older adults with difficulty walking may use up to two times this energy (9). As a consequence, walking can be physiologically demanding for older adults, occupying up to 90% of reserve aerobic capacity (6), likely contributing to high perceived fatigability during walking (13). Fatigability is a major source of activity limitation, such that older adults may opt to walk more slowly or walk less to minimize fatigue (6,14). Therefore, a high energy cost of walking can have profound negative impacts on an older adult’s overall mobility, causing decreases in the speed and quantity of movement. Reductions in the energy cost of walking could thus decrease fatigability and thereby increase daily physical activity, endurance, physical function, and life-space.

Very few studies have attempted to reduce the energy cost of walking among older adults through exercise. Traditional multicomponent exercise interventions that target impairments in strength, aerobic capacity, range of motion and balance lead to improvements in physical function, including leg strength, standing balance, and walking endurance, but they do not reduce the energy cost of walking (9,15,16). The most promising intervention to reduce the energy cost of walking is based on principles of motor skill acquisition and focuses on training the timing and coordination of gait (9,17). Among older adults with slow and variable gait, 12 weeks of one-to-one physical therapist instructed timing and coordination training reduced the energy cost of walking by 15% (9). It remains unknown whether this reduction in energy cost is sustained following training cessation, and there has been limited investigation of intervention effects on fatigability, daily physical activity, endurance, physical function, and life-space. Moreover, effectiveness has not been reported when delivered in small-group settings by certified fitness instructors to community-dwelling older adults selected for self-reported mobility limitation. Such a delivery mechanism would be more scalable than one-to-one physical therapist led training.

Alternatively, aerobic exercise and walking practice may improve walking energetics, as aerobic exercise improves oxidative metabolism in active muscles, and practice is a fundamental component of motor learning to enhance motor skill. Thus, the regular practice of walking may also improve gait efficiency, but no trial has assessed the effect of aerobic walking on the energy cost of walking.

The study purpose was to test the hypothesis that two independent, 12-week, twice-weekly group exercise programs (timing and coordination, aerobic walking) could reduce the energy cost of walking and fatigability, and increase daily physical activity, endurance, physical function, and life-space mobility among community-dwelling older adults with mobility limitation.

Research Design and Methods

Research Design

We conducted the HealthySteps Study, a three-arm, 12-week, pilot randomized controlled trial of exercise among older adults with mobility limitation (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01740505). Descriptive measurements and outcomes were assessed at baseline (T0), 12 weeks (intervention end, T1), and 24 weeks (follow-up end, T2). Outcome assessors were blinded to intervention assignments at T0 only. The trial was approved by the Research Ethics Boards at Simon Fraser University and Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, and was conducted at the Centre for Hip Health and Mobility, in Vancouver, Canada.

Participants

Participant recruitment primarily focused on newspaper, poster, and email advertisement in the Vancouver and Burnaby area. Participant eligibility was determined by telephone screening using a standardized questionnaire (~15–30 minutes). Older adults were recruited to meet the following criteria at telephone screening: (a) ≥65 years; (b) living independently in the community as opposed to residing at an assisted-living or long-term care site; (c) reported mobility limitation, defined as difficulty walking one-quarter mile or climbing one flight of stairs (1,18); (d) able to walk without assistance; and (e) willing to be randomized. Similar to past research (13), we excluded those with the following: (a) history of medical conditions that might alter gait energetics or the ability to safely complete treadmill walking or exercise classes (eg, recent heart attack or excessive pain); (b) exercise trial participation in past 6 months; (c) moderate-to-vigorous intensity walking for ≥30 minutes twice per week; (d) unable to wear an armband activity monitor for 1 week; or (e) not fluent in English. Following telephone screening, eligible individuals were mailed a package containing study information, informed consent form, and a letter for their physician to sign indicating the individual’s appropriateness to participate in an exercise program. Participants were also asked to attend a 60-minute in-person information session at the research center where they learned details about the intervention groups and randomization. The session concluded with provision of written informed consent (Figure 1).

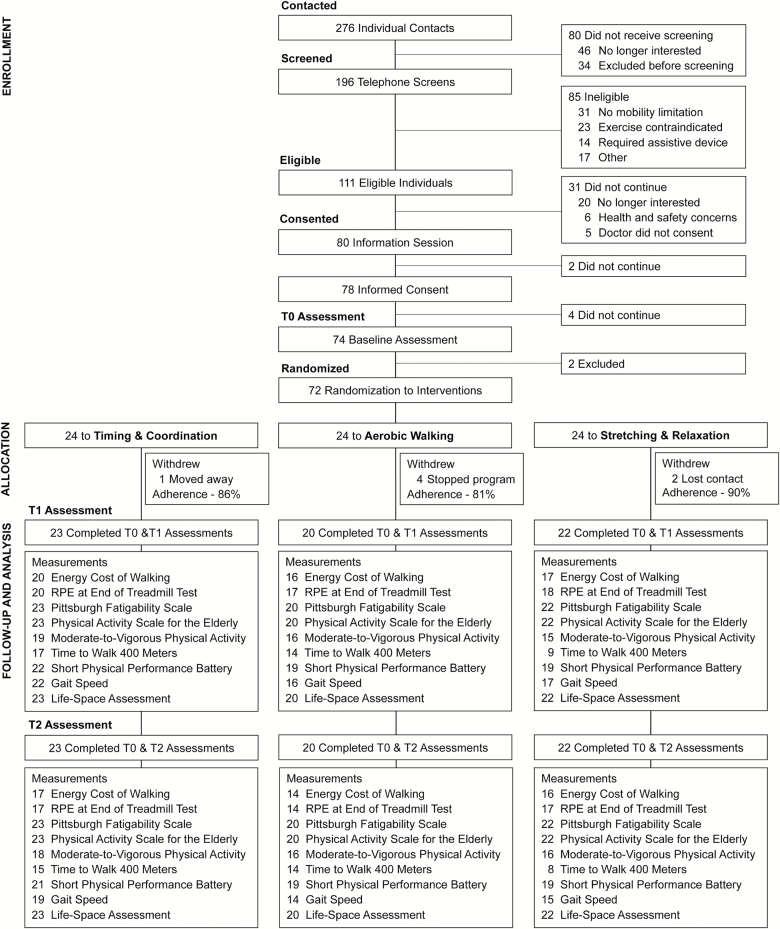

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the HealthySteps Study. Note: T0, baseline; T1, 12-week follow-up; T2, 24-week follow-up. Average intervention adherence was calculated by excluding seven participants who withdrew from the study between T0 and T1. Average adherence for the participants who attended ≥1 intervention class was 84% for timing and coordination, 75% for aerobic walking, and 84% for stretching and relaxation.

Measurements

Descriptive measurements

Height and weight were measured (SECA 2841300109). Body mass index was calculated. Sex, age, race, and self-rated health were ascertained by standard questionnaire. Participants reported if they currently smoked or if they had ever smoked on a regular basis, defined as daily for at least 6 months. Alcohol consumption was reported as the average number of alcoholic drinks consumed per week. Participants self-reported if a medical professional had ever diagnosed them with each listed disease or condition. Global cognitive function was assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination from 0 to 100 (19). Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale from 0 to 60 (20).

Primary outcome measurement

Energy cost of walking.

We determined mean energy cost of walking (mL O2/kg/m) during submaximal walking by measuring the rate of oxygen consumption (mL/min) with a portable metabolic system (Cosmed K4b2, Rome, Italy) (21). After being outfitted, participants adapted to the equipment and became familiar with treadmill walking before data collection. Light-weight portable metabolic monitors, such as the Cosmed K4b2, do not impact gait characteristics of older adults with mobility limitation (22). Participants then walked for 5 minutes at 0.8 m/s on a motor-driven treadmill (0° incline). This speed was chosen to maximize participant inclusion without being uncomfortably slow (13).

To calculate mean during steady state, beginning breath-by-breath data were discarded while participants adjusted to the workload to reach stable and the remaining data were averaged. If the 5-minute test was completed, we discarded the first 3 minutes of data and averaged the final 2 minutes. If the participant or examiner chose to end the test early such that test duration was 3 to <5 minutes, we discarded the first 2 minutes of data and averaged the remaining minutes. If test duration was <3 minutes, data were excluded from analysis. Mean was then converted to mean energy cost of walking per unit distance (mL/kg/m) (13).

Secondary outcome measurements

We assessed secondary outcomes related to the World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health domains (23) of activity (fatigability, endurance, physical function) and participation (daily physical activity, life-space mobility).

Fatigability.

Perceived fatigability (self-reported fatigue in relation to a standardized task (24)), was assessed using the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Scale from 6 to 20 (25) at the end of the 0.8 m/s treadmill test (13). Physical fatigability, scored from 0 to 50, was assessed with the Pittsburgh Fatigability Scale (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.88) (26); participants rated their physical fatigue from 0 (“no fatigue”) to 5 (“extreme fatigue”) for 10 activities of specified intensity and duration.

Daily physical activity.

We measured daily self-reported occupational, household, and leisure physical activities over the past 7 days using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly from 0 to 400 (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.69) (27). We also measured mean time (mins/day) spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA, 3+METs) using the SenseWear Pro armband (Bodymedia, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA). Participants were instructed to wear the armband for 7 days following each assessment; we calculated MVPA over a minimum of 5 valid wear days (wear time > 90% of 24 hours).

Endurance.

Endurance was measured as minutes to complete a 400-m overground walk (20 m per segment) with the instruction to “walk as quickly as you can, without running, at a pace you can maintain” (28).

Physical function.

The Short Physical Performance Battery, scored from 0 to 12, assessed lower extremity physical function based on standing balance, usual 6-m gait speed, and time to complete five chair stands (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.76) (18,29). We also measured usual gait speed on a 3-minute overground course with instructions to “walk at your usual pace without overexerting yourself.”

Life-space mobility.

The Life-Space Assessment measured the extent, frequency, and independence of movement during the prior 4 weeks across five life-space levels (30). Composite scores ranged from 0 (restricted to one’s bedroom on a daily basis) to 120 (travels out of one’s town without assistance daily) (30).

Randomization

Randomization of participants in 1:1:1 ratio was performed by a research assistant after T0 assessments. The sequence was computer generated and concealed by the research assistant until interventions were assigned.

Sample Size

We calculated that 22 participants per group would yield statistical power of 0.80 to detect a clinically meaningful 15% reduction in energy cost of walking between the exercise and control groups with a two-sided alpha of 0.05 and 20% loss to follow-up over 12 weeks. We estimated baseline mean energy cost of walking would be 0.25–0.30 mL/kg/m with SD of 0.06 mL/kg/m (13).

Interventions

Participants were scheduled for two, small-group (≤8 participants), 60-minute classes per week for 12 weeks. Classes were led by certified fitness instructors who received in-person training specific to three interventions: timing and coordination of gait training, outdoor aerobic walk training, and stretching and relaxation training. All classes involved 10 minutes warm-up, 40 minutes intervention-specific content, and 10 minutes cool down. Participants were not blinded to their assigned intervention; however, they were instructed not to discuss their assignment with other participants, and they were only permitted to attend their assigned classes. The project coordinator conducted quality assurance assessments every four weeks to correct inconsistencies in intervention delivery versus protocol. At intervention end, all participants received a list of exercise programs within their communities.

Timing and coordination of gait training

The timing and coordination program was adapted from a published goal-oriented motor skill training program (17) and focused on stepping patterns (~10–20 min/class) and walking patterns (~10–20 min/class) to promote timing and coordination within the gait cycle. Stepping patterns involved forward, backward, and diagonal (across the body midline) steps with both feet. Walking patterns incorporated sequences of ovals, spirals, and serpentines. Participants were instructed to maintain consistent walking speed while turning and moving in a straight line. Progression for stepping and walking was accomplished by increases in speed, amplitude, and complexity of performance. To increase complexity, tasks involving object manipulation were added (eg, bouncing a ball while stepping or walking), and more complex tasks that combined different activities were incorporated into the training sessions (eg, walking past other people while bouncing a ball). Changes to speed, amplitude, and complexity were progressed one item at a time. Treadmill walking at preferred speed (~10–15 min/class) was also completed to reinforce rhythmic stepping. Brief increases in speed (ie, 10% for 30–60 seconds) were used to reinforce timing of gait, but were not intended to increase endurance or raise perceived effort.

Outdoor aerobic walk training

The aerobic walking group focused on outdoor walking in surrounding neighborhoods. Exercise intensity was prescribed and monitored for each class using the Borg RPE scale (25). Target RPE was set by the instructor and monitored subjectively at the start, mid-point, and end of class. Participants were instructed to gradually progress walking intensity over the intervention to a target RPE of 14–15, corresponding to “hard” (25). To further guide intensity, participants were instructed to use a simple “talk” test and to initially walk at a pace they could talk comfortably without effort and gradually progress to a pace at which conversation required more effort. Within each group, participants walked in small subgroups to accommodate variability in speed. Walking routes increased in length and incorporated more slopes as the intervention progressed. Walking intensity was intended to remain constant during a given class. Therefore, the aerobic walking intervention was not intended to be comparable to interval training.

Stretching and relaxation training

The stretching and relaxation group served as an active control to account for potential effects related to traveling to the training center, social interactions, and changes in lifestyle secondary to study participation. Each class involved full-body stretching, range-of-motion exercises, and relaxation techniques for which there was no available evidence to suggest an effect on energy cost of walking. No gait training was included.

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables were summarized as mean (SD), and categorical variables as N (%). We compared continuous primary and secondary outcomes between each exercise group and the control group (ie, timing and coordination vs stretching and relaxation; aerobic walking vs stretching and relaxation) using an analysis of covariance model with Tukey multiple comparisons procedure for post hoc testing. We analyzed intervention effects by comparing T1 measurements between exercise and control groups, adjusting for T0 measurements. We analyzed sustained effects by comparing T2 measurements between exercise and control groups, adjusting for T0 measurements. We did not adjust for any other covariates beyond T0 measurements. Given the pilot nature of this trial, we did not adjust the significance level to account for multiple comparisons.

We performed standard intention-to-treat analysis for each outcome. We also completed as-treated analysis for each outcome by restricting to participants with ≥85% class adherence. Finally, we conducted a subgroup analysis for the energy cost of walking outcome to determine if those with high baseline energy cost (>overall median) had greater effects. Past research has used this approach to yield subgroups of similar size (9). Alpha was 0.05 for intention-to-treat and as-treated analyses. The subgroup analysis was exploratory, so alpha was 0.20 (31). Consistent with current recommendations for the analysis of data from randomized controlled trials, we did not test for statistical differences in baseline participant characteristics between groups (32–34). Analyses were performed using R, version 1.0.44 (RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA).

Results

Participant Flow and Intervention Adherence

Of 196 individuals screened by telephone, 72 were randomized (Figure 1). Average intervention adherence was 86%. Seven participants withdrew from the study, while 65 (90%) completed T1 and T2 assessments. The energy cost of walking test was completed by 67 participants at T0, 58 at T1, and 50 at T2.

Participant Characteristics

At baseline, participants had mean age of 74.2 (SD: 6.6) years, and were predominantly white (67%) women (74%), with 61% reporting osteoarthritis, and mean BMI within the obese range (30.2, SD: 6.3 kg/m2; Table 1). Mean gait speed was 0.9 (SD: 0.2) m/s, and mean energy cost of walking was 0.260 (SD: 0.052) mL/kg/m. Participant characteristics were well balanced at T0.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics (n = 72)

| Characteristic | Timing and Coordination (n = 24) | Aerobic Walking (n = 24) | Stretching and Relaxation (n = 24) | Total (n = 72) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women, N (%) | 17 (70.8) | 18 (75.0) | 18 (75.0) | 53 (73.6) |

| Age (years) | 73.6 (6.3) | 74.4 (6.8) | 74.7 (6.9) | 74.2 (6.6) |

| Race, N (%) | ||||

| White | 16 (66.7) | 17 (70.8) | 15 (62.5) | 48 (66.7) |

| Chinese | 4 (16.7) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | 11 (15.3) |

| Other | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | 6 (25.0) | 13 (18.1) |

| Good/excellent health, N (%) | 14 (58.3) | 8 (33.3) | 11 (45.8) | 33 (45.8) |

| Teng Mini Mental (/100) | 90.0 (9.6) | 93.3 (4.8) | 89.9 (9.1) | 91.1 (8.2) |

| CES-D ≥ 16,aN (%) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (12.5) | 5 (20.8) | 10 (13.9) |

| Smoking status, N (%) | ||||

| Never | 15 (62.5) | 13 (54.2) | 13 (54.2) | 41 (56.9) |

| Current | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.8) |

| Past | 8 (33.3) | 10 (41.7) | 11 (45.8) | 29 (40.3) |

| <1 Alcoholic drink/week, N (%) | 18 (75.0) | 12 (50.0) | 18 (75.0) | 48 (66.7) |

| Medical history, N (%) | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (4.2) | 4 (16.7) | 2 (8.3) | 7 (9.7) |

| Stroke | 3 (12.5) | 3 (12.5) | 2 (8.3) | 8 (11.1) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.8) |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 1 (4.2) | 5 (20.8) | 6 (25.0) | 12 (16.7) |

| Osteoarthritis | 15 (62.5) | 15 (62.5) | 14 (58.3) | 44 (61.1) |

| Depression | 7 (29.2) | 2 (8.3) | 4 (16.7) | 13 (18.1) |

| Cancer | 4 (16.7) | 9 (37.5) | 10 (41.7) | 23 (31.9) |

| Fallen in the last 12 months, N (%) | 9 (37.5) | 7 (29.2) | 8 (33.3) | 24 (33.3) |

| 1 time | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | 3 (12.5) | 10 (13.5) |

| 2+ times | 5 (20.8) | 4 (16.7) | 5 (20.8) | 14 (19.4) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.6 (5.8) | 29.6 (6.3) | 31.5 (6.8) | 30.2 (6.3) |

Note: Cells are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

aCentre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (/60) ≥16 is suggestive of depressive symptoms.

Primary Outcome: Energy Cost of Walking

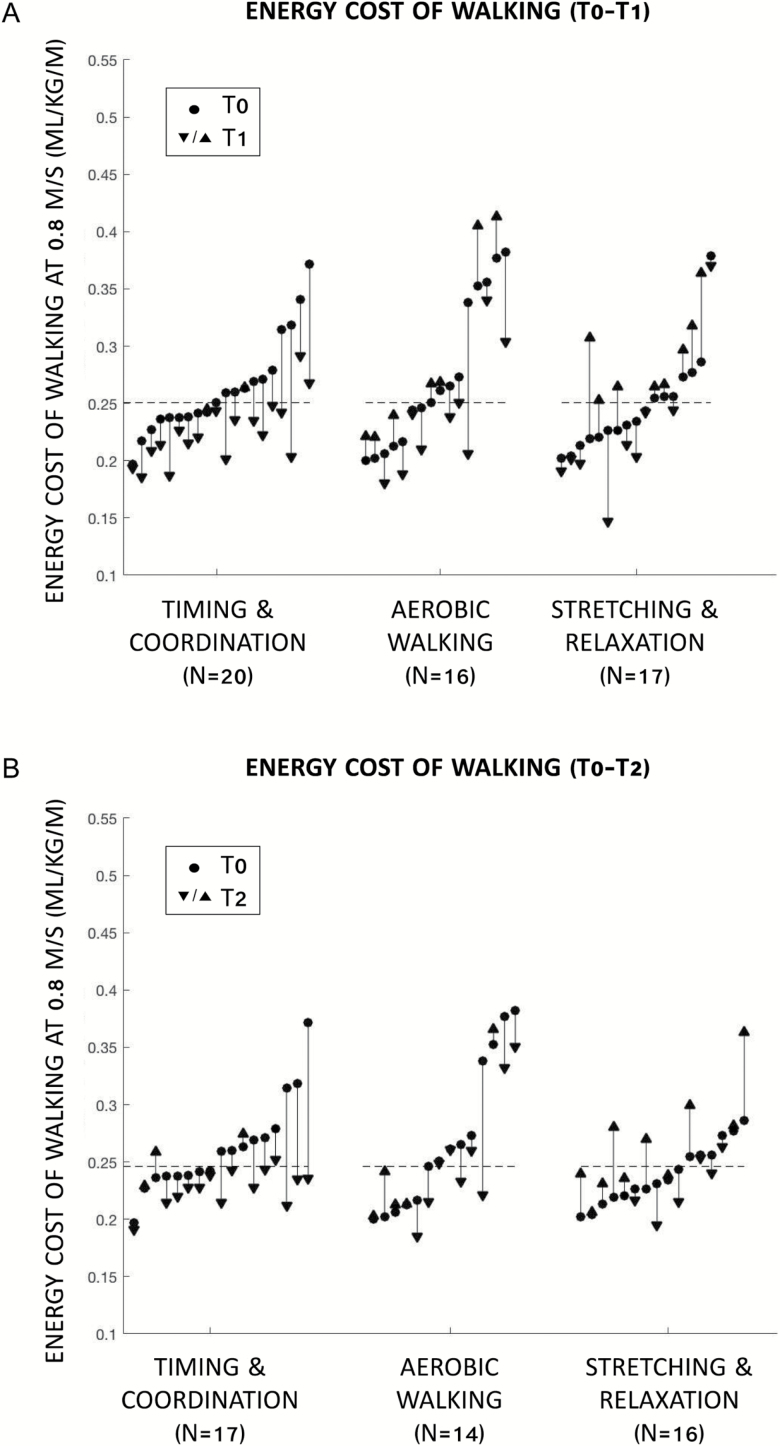

At T1, timing and coordination reduced mean energy cost of walking by 15% compared with stretching and relaxation (adjusted mean difference = −0.040 mL/kg/m, p = .008) (Table 2; Figure 2A). Results were consistent after restricting to adherence ≥85% (n = 29, p = .025). In subgroup analysis, timing and coordination reduced mean energy cost by 20% compared with stretching and relaxation (adjusted mean difference = −0.062 mL/kg/m, p = .055) among those with high baseline cost (>median = 0.251 mL/kg/m), but had no effect among those with low baseline cost (p = .997).

Table 2.

Energy Cost of Walking (mL/kg/m) on Treadmill at 0.8 m/s (n = 72)

| Adjusted Mean (95% CI) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing and Coordination | Aerobic Walking | Stretching and Relaxation | Timing and Coordination Vs Stretching and Relaxation | Aerobic Walking Vs Stretching and Relaxation | |

| T1 | 0.227 (0.210 to 0.244) |

0.252 (0.233 to 0.272) |

0.267 (0.248 to 0.285) |

−0.040 (−0.070 to −0.009) |

−0.014 (−0.047 to 0.018) |

| p = .008* | p = .549 | ||||

| T2 | 0.229 (0.213 to 0.245) |

0.245 (0.228 to 0.263) |

0.262 (0.246 to 0.278) |

−0.033 (−0.060 to −0.005) |

−0.017 (−0.046 to 0.013) |

| p = .016* | p = .359 | ||||

Note: Comparisons are reported between exercise (timing and coordination, aerobic walking) and active control (stretching and relaxation) groups. T0, baseline; T1, 12-week follow-up; T2, 24-week follow-up. Adjusted mean, adjusted for T0. Mean difference, analysis of covariance adjusted for T0. Sample sizes: timing and coordination: T0 (n = 22), T1 (n = 22), T2 (n = 18); aerobic walking: T0 (n = 23), T1 (n = 17), T2 (n = 15); stretching and relaxation: T0 (n = 21), T1 (n = 18), T2 (n = 17).

*p < .05.

Figure 2.

Participant measurements of the energy cost of walking at 0.8 m/s. (A) Intervention effects: baseline (T0) to 12-week follow-up (T1). (B) Sustained effects: T0 to 24-week follow-up (T2). Note: Dashed lines represent median baseline energy cost across all participants.

At T2, the intervention group differences were sustained, with a 13% reduction in mean energy cost of walking for timing and coordination compared with stretching and relaxation (adjusted mean difference = −0.033 mL/kg/m, p = .016; Table 2, Figure 2B). At T2, results were consistent after restricting to adherence ≥85% (n = 27, p = .028). In subgroup analysis, timing and coordination reduced mean energy cost by 16% compared with stretching and relaxation (adjusted mean difference = −0.044 mL/kg/m, p = .160) among those with high baseline cost (>median = 0.246 mL/kg/m), but had no effect among those with low baseline cost (p = .997).

Aerobic walking had no effect on mean energy cost of walking compared with stretching and relaxation at T1 (p = .549) or T2 (p = .359; Table 2). Results were unchanged at T1 and T2 after restricting to adherence ≥85% and stratifying by baseline energy cost.

Secondary Outcomes

Compared with stretching and relaxation, neither timing and coordination nor aerobic walking led to significant changes in fatigability, daily physical activity, endurance, lower extremity physical function, or life-space mobility at T1 or T2 based on intention-to-treat and as treated analyses (Supplementary Tables 1–5). However, we observed a trend toward a 10% increase in gait speed for timing and coordination compared with stretching and relaxation at T1 (mean difference = 0.10 m/s, p = .074; Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion and Implications

In community-dwelling older adults aged 65–90 with self-reported mobility limitation, 12 weeks of twice-weekly timing and coordination training reduced the energy cost of walking by 15% relative to an active control; the reduction in energy cost was greater among those with high baseline energy cost. The reduction in energy cost was sustained 12 weeks after intervention end, particularly among those with high baseline energy cost. There was a trend for timing and coordination to increase usual gait speed by a clinically meaningful amount of 0.10 m/s.

This study replicates and extends work by VanSwearingen and colleagues (9,35) and Brach and colleagues (16,36) who have reported that 12 weeks of one-to-one physical therapist guided, twice-weekly timing and coordination training improved energetic cost, speed, skill, and walking confidence among older adults with a range of walking difficulties. Our results suggest the timing and coordination training effects are sustained following 12-weeks of training cessation, which has not been previously reported, and they appear to be robust to intervention setting, delivery mode, and participant group. Specifically, we demonstrated that timing and coordination training can be effectively delivered to small groups of older adults with self-reported mobility limitation in community settings by fitness instructors. The effect size reduction in the energy cost of walking was consistent with those of one-to-one physical therapist guided interventions (17), and average intervention adherence was high at 86%.

The reduction in energy cost of walking was not accompanied by a corresponding reduction in fatigability, as was predicted from Schrack’s energetic pathway to mobility loss (7). One explanation is that the moderate reduction in energy cost of walking was not large enough to cause perceivable changes in fatigability. A longer duration trial that elicits larger reductions in energy cost may lead to changes in fatigability. Another explanation is that older adults with walking difficulty have a high level of fatigability, developed over years of experience, that is, insensitive to change. Indeed, each group had high mean baseline Pittsburgh Fatigability Scale scores of ≥20 (26).

We observed a trend toward a clinically meaningful increase in gait speed of 0.1 m/s at intervention end in timing and coordination compared with control, consistent with other trials of timing and coordination (9,16). Timing and coordination did not, however, lead to discernable meaningful changes in other outcomes theorized to be downstream of energy cost of walking (7), including daily physical activity, endurance, lower extremity physical function, or life-space. Timing and coordination training did not specifically target lower extremity strength or endurance, which may be necessary to realize improvements in these domains secondary to reduced energetic cost. Timing and coordination training also did not incorporate behavior change techniques, which may be necessary to achieve improvements in daily physical activity and life-space.

Aerobic walking did not improve energy cost of walking or any downstream secondary outcome. Walking difficulty in older adults is typically attributed to age-related changes in the biomechanics and motor control of walking that impose inefficiencies within the gait cycle that produce slow, inefficient, and unskilled movement (17). Our results suggest that regularly practicing outdoor walking for a short period of time (12 weeks) may not address these age-related changes.

The HealthySteps Study has certain limitations. First, as this was a pilot study, the sample size was small, and the study was not designed or powered to detect changes in the secondary outcomes. The effect size and variability estimates observed in HealthySteps, however, may help to plan appropriate sample sizes for future trials. Second, screening participants for inclusion based on self-reported mobility limitation was efficient and precluded the need for in-person screening; however, it yielded a large degree of variability in baseline energy cost of walking. Since participants with higher baseline energy cost experienced larger reductions in the energy cost of walking, future studies may benefit by screening for energy cost. Third, outcome assessors were not blinded to assignments at T1 or T2, but the potential for bias was small because outcomes were objective and assessments were standardized. Fourth, the results of this study apply specifically to community-dwelling older adults with self-reported mobility limitation who are able to walk without assistance, and they may not generalize to other segments of the older adult population with different mobility statuses.

In conclusion, we provide novel evidence that a 12-week timing and coordination exercise program delivered by fitness instructors to small groups of community-dwelling older adults with mobility limitation led to a reduction in the energy cost of walking, particularly among those with high baseline energy cost, which was sustained following 12-weeks of training cessation. Timing and coordination also led to a trend toward faster gait speed. These results suggest that it may be beneficial to incorporate timing and coordination training in community-based exercise programs for older adults that are designed to make walking easier and faster. A larger, definitive trial is warranted to examine effects of timing and coordination training on longer-term outcomes including mobility disability.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Innovation in Aging online.

Funding

This work was supported by a Drummond Foundation 2011 Medical Grant [to D.C.M.]. D.C.M. was supported by a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. A presentation on this study was made at the Simon Fraser University Biomedical Physiology and Kinesiology Research Day, March 2017.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the study participants, the three fitness instructors who led all HealthySteps exercise classes (Bonnie McCoy, Danielle Scheier, and Debbie Sharun), and staff at the Centre for Hip Health and Mobility who assisted with assessments and study events. Author’s Contributions: K.J.C. contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising the article critically for intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. J.A.S. and N.W.G. contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, revising the article critically for intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. J.M.V. contributed to study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, revising the article critically for intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. M.C.P. and V.E.G. contributed to study design, acquisition of data, revising the article critically for intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. D.C.M. contributed to study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising the article critically for intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published.

References

- 1. Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Visser M, et al. ; Health, Aging and Body Composition Study Mobility limitation in self-described well-functioning older adults: importance of endurance walk testing. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:841–847. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.8.841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shumway-Cook A, Ciol MA, Yorkston KM, Hoffman JM, Chan L. Mobility limitations in the Medicare population: prevalence and sociodemographic and clinical correlates. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1217–1221. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53372.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wolinsky FD, Miller DK, Andresen EM, Malmstrom TK, Miller JP. Further evidence for the importance of subclinical functional limitation and subclinical disability assessment in gerontology and geriatrics. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:S146–S151. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.3.S146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Foley DJ, Ostfeld AM, Branch LG, Wallace RB, McGloin J, Cornoni-Huntley JC. The risk of nursing home admission in three communities. J Aging Health. 1992;4:155–173. doi: 10.1177/089826439200400201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hirvensalo M, Rantanen T, Heikkinen E. Mobility difficulties and physical activity as predictors of mortality and loss of independence in the community-living older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:493–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04994.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fiser WM, Hays NP, Rogers SC, et al. Energetics of walking in elderly people: factors related to gait speed. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:1332–1337. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schrack JA, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L. The energetic pathway to mobility loss: an emerging new framework for longitudinal studies on aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(Suppl 2):S329–S336. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02913.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schrack JA, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L. The relationship of the energetic cost of slow walking and peak energy expenditure to gait speed in mid-to-late life. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92:28–35. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3182644165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. VanSwearingen JM, Perera S, Brach JS, Cham R, Rosano C, Studenski SA. A randomized trial of two forms of therapeutic activity to improve walking: effect on the energy cost of walking. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1190–1198. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. VanSwearingen JM, Studenski SA. Aging, motor skill, and the energy cost of walking: implications for the prevention and treatment of mobility decline in older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:1429–1436. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malatesta D, Simar D, Dauvilliers Y, et al. Energy cost of walking and gait instability in healthy 65- and 80-yr-olds. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2003;95:2248–2256. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01106.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Waters RL, Mulroy S. The energy expenditure of normal and pathologic gait. Gait Posture. 1999;9:207–231. doi:10.1016/s0966-6362(99)00009-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Richardson CA, Glynn NW, Ferrucci LG, Mackey DC. Walking energetics, fatigability, and fatigue in older adults: the study of energy and aging pilot. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:487–494. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vestergaard S, Nayfield SG, Patel KV, et al. Fatigue in a representative population of older persons and its association with functional impairment, functional limitation, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:76–82. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mian OS, Thom JM, Ardigò LP, Morse CI, Narici MV, Minetti AE. Effect of a 12-month physical conditioning programme on the metabolic cost of walking in healthy older adults. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;100:499–505. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0141-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brach JS, Van Swearingen JM, Perera S, Wert DM, Studenski S. Motor learning versus standard walking exercise in older adults with subclinical gait dysfunction: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1879–1886. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brach JS, VanSwearingen JM. Interventions to improve walking in older adults. Curr Transl Geriatr Exp Gerontol Rep. 2013;2:230–238. doi: 10.1007/s13670-013-0059-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:314–318. doi:10.1007/springerreference_183334 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schrack JA, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L. Comparison of the Cosmed K4b(2) portable metabolic system in measuring steady-state walking energy expenditure. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wert DM, VanSwearingen J, Perera S, Studenski S, Brach JS. The impact of a portable metabolic measurement device on gait characteristics of older adults with mobility limitations. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2016;39:77–82. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0000000000000053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2002:1–22. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/training/icfbeginnersguide.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eldadah BA. Fatigue and fatigability in older adults. PM R. 2010;2:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Borg G. Ratings of perceived exertion and heart rates during short-term cycle exercise and their use in a new cycling strength test. Int J Sports Med. 1982;3:153–158. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1026080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glynn NW, Santanasto AJ, Simonsick EM, et al. The Pittsburgh Fatigability scale for older adults: development and validation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:130–135. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153–162. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Naydeck BL, et al. Association of long-distance corridor walk performance with mortality, cardiovascular disease, mobility limitation, and disability. JAMA. 2006;295:2018–2026. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.M85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peel C, Baker PS, Roth DL, Brown CJ, Brodner EV, Allman RM. Assessing mobility in older adults: the UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment. Phys Ther. 2005;85:1008–1119. doi: 10.1093/ptj/85.10.1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schoenfeld D. Statistical considerations for pilot studies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1980;6:371–374. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(80)90153-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Senn S. Testing for baseline balance in clinical trials. Stat Med. 1994;13:1715–1726. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roberts C, Torgerson DJ. Baseline imbalance in randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1999;319:185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7203.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Friedman LM, Furberg CD, DeMets DL, Reboussin DM, Granger CB. Baseline Assessment. In: Fundamentals of Clinical Trials. 5th ed Switzerland: Springer; 2015: 201–214. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18539-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. VanSwearingen JM, Perera S, Brach JS, Wert D, Studenski SA. Impact of exercise to improve gait efficiency on activity and participation in older adults with mobility limitations: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2011;91:1740–1751. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brach JS, Lowry K, Perera S, et al. Improving motor control in walking: a randomized clinical trial in older adults with subclinical walking difficulty. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.