Abstract

Introduction

As a causal organism in infective endocarditis, Burkholderia pseudomallei is rare. Burkholderia pseudomallei is intrinsically resistant to aminoglycosides but a gentamicin-susceptible strain was discovered in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo in 2010. We report the first occurrence of infective endocarditis due to the gentamicin-susceptible strain of B. pseudomallei.

Case presentation

A 29-year-old man presented with pneumonia and melioidosis septicaemia. His condition was complicated with infective endocarditis and septic emboli to the brain. Despite difficulties in reaching a diagnosis, the patient was successfully treated using intravenous gentamicin and ceftazidime and was discharged well.

Discussion

The role of gentamicin in the treatment of the gentamicin-susceptible strain of B. pseudomallei remains unclear.

Keywords: Melioidosis, Infective endocarditis, Gentamicin, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Case report, Bintulu, Sarawak, Malaysia, Borneo, Gentamicin susceptible strain

Learning points

Burkholderia pseudomallei is an unusual cause of infective endocarditis.

Burkholderia pseudomallei is known to be resistant to many antibiotics, including aminoglycosides. A strain of B. pseudomallei that is gentamicin-susceptible was found in Sarawak in Malaysian Borneo in 2010.

The standard intensive phase therapy using carbapenem or ceftazidime can be instituted together with intravenous gentamicin for its synergistic effect in the treatment of infective endocarditis caused by the gentamicin susceptible strain of B. pseudomallei.

Introduction

Melioidosis is caused by the bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei. It is endemic in many regions in Southeast Asia and Northern Australia.1 It is also increasingly reported in other tropical countries.1 It has a high mortality rate due to its systemic involvement and intrinsic resistance to a myriad of antibiotics.2 A novel strain of gentamicin-susceptible B. pseudomallei was recently reported to be predominantly found in the central region of Sarawak in Malaysian Borneo.3

Infective endocarditis causes significant morbidity and mortality.4,5 Complications of infective endocarditis include thromboembolic events, which could be life-threatening. Treatment of infective endocarditis requires the administration of an effective intravenous (IV) antibiotic over a prolonged duration.6 Common organisms identified for infective endocarditis are Streptococci and Staphylococci, both of which contributed to 80% of cases.6

We report the first occurrence of infective endocarditis due to the gentamicin-susceptible strain of B. pseudomallei in a tertiary hospital in central Sarawak of Malaysian Borneo.

Timeline

| Week | Day | Patient’s progress | Culture site | Culture result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Septic shock secondary to pneumonia | Blood | Burkholderia pseudomallei |

| Stared intravenous (IV) ceftazidime and IV C-penicillin | ||||

| 3–4 | Developed ventilator associated pneumonia | — | — | |

| 6 | Blood culture taken on first day confirmed for B. pseudomallei | Blood | B. pseudomallei | |

| 2 | 8 | Weaned off inotrope | Respiratory tract | Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumanii |

| 11 | — | Respiratory tract | Multidrug-resistant A. baumanii | |

| 12 | — | Blood | B. pseudomallei | |

| 14 | Started on oral bactrim | |||

| 24 | — | Blood | No growth | |

| 3 | 25 | Left side hemiplegia and pansystolic murmur | ||

| Echocardiography and computed tomography of the brain done | ||||

| 26 | — | Blood | No growth | |

| 27 | Weaned from ventilator support | Blood | No growth | |

| 5 | Started on IV gentamicin | |||

| 7 | Completed intensive phase of antibiotics and physiotherapy. Patient was discharged from hospital | |||

| 36 | Last follow-up visit |

Case presentation

The patient, a regular and heavy consumer of alcohol, was a 29-year-old male lumberjack with no known medical illness. He had been having fever and cough for 2 weeks. He was brought to the hospital in a confused state after being reported missing from work for a few days.

The patient presented with septic shock, which was consistent with the definition of Sepsis-3.7 He was in a very confused state and was talking irrelevantly. His Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) registered E4V2M5. His temperature was 38.0°C, blood pressure was 85/42 mmHg, and his pulse rate was 135 b.p.m. He also had neck stiffness, bilateral upper and lower limbs power registered at least three, while his tone and reflexes were normal. He had normal heart sounds with no murmur and bilateral lung crepitations. The patient was given fluid resuscitation and required a vasopresssor for blood pressure support. He was also put on a mechanical ventilator before being admitted into the intensive care unit (ICU).

Initial blood investigations showed anaemia and thrombocytopenia with normal total white cells and renal function. Ultrasonography examination showed the presence of splenic microabscesses and chest radiograph showed bilateral lung fields consolidation. Computed tomography (CT) of the brain was normal and lumbar puncture examination of the cerebrospinal fluid on admission showed no signs of inflammation or infection.

The patient’s blood culture taken on admission grew B. pseudomallei. This was confirmed by a real-time polymerase chain reaction assay targeting the type III secretion system (TTS1).8 This B. pseudomallei isolate appeared to be gentamicin-susceptible by the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion susceptibility test (Table 1). He remained bacteraemic with positive blood cultures on Day 6 and 12 of admission yielding B. pseudomallei with the same antibiogram pattern. Subsequent blood cultures on Day 24, 26 and 27 of admission had no growth.

Table 1.

Antibiogram of B. pseudomallei isolate based on disk diffusion test

| Antibiotics tested | Disk diffusion result |

|---|---|

| Ampicilin | Sensitive |

| Ceftazidime | Sensitive |

| Ciprofloxacin | Sensitive |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Sensitive |

| Imipenem | Sensitive |

| Meropenem | Sensitive |

| Tetracycline | Sensitive |

| Gentamicin | Sensitive |

The patient was administered IV noradrenaline upon admission. The highest dose used was 0.27 mcg/kg/min on Day 4 of admission, and he was subsequently weaned off after a week. Upon admission, he was empirically given IV ceftazidime and IV C-penicillin. On Day 4 of admission, antibiotics were escalated to IV imipenem in view of the patient’s persistent high-grade temperature and leukopenia. He required ventilatory support on a high setting for 2 weeks. During the second week of intensive phase therapy with IV antibiotics, he was started on oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (co-trimoxazole). His condition was complicated with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Culture of endotracheal secretions grew a multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumanii, which was treated successfully with high dose IV ampicilin-sulbactamfor 14 days. He also developed sepsis-induced supraventricular tachycardia which resolved spontaneously.

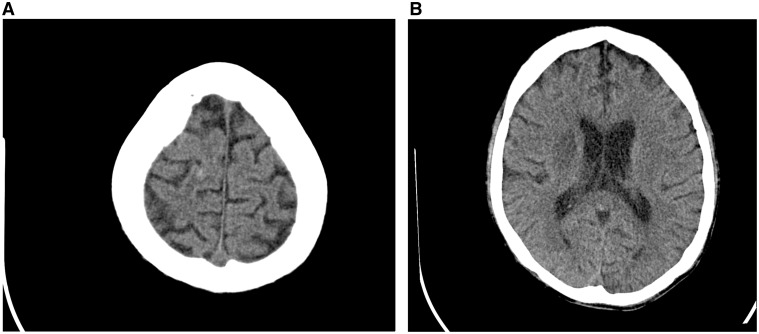

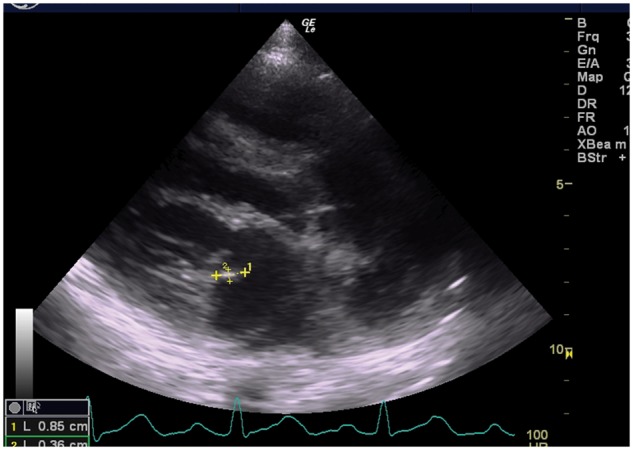

In the third week of admission, there was a new onset of left-sided hemiparesis (muscle power 1/5) and pansystolic murmur with thrills at the apex of the heart. A repeat CT of the brain showed a right corona radiata infarct with a high parietal petechia haemorrhage (Figure 1). An echocardiogram showed a thickened mitral valve with an oscillating mass at the posterior mitral valve leaflet suggestive of vegetation (Figure 2) with a moderate eccentric mitral regurgitation.

Figure 1.

(A) Axial plain computed tomography brain shows there is a small hyperdense punctate haemorrhage at right high parietal region. (B) Axial plain computed tomography brain shows ill-defined hypodense area at right basal ganglia in keeping with infarction.

Figure 2.

Echocardiogram of parasternal long-axis view showed an oscillating mass of 0.3 cm × 0.8 cm attached to posterior mitral leaflet suggestive of vegetation.

The intensive phase therapy for melioidosis was extended to 6 weeks using IV ceftazidime, and we added IV gentamicin at the dose of 60 mg, 8-hourly for 14 days. He was also given concurrent oral co-trimoxazole, which was subsequently continued as monotherapy in the eradication phase therapy for melioidosis.

He was discharged after 12 weeks of admission with minimal residual left sided weakness (Modified Rankin Score of 2). The patient was able to perform all activities of daily living independently with intact cognitive function. He was subsequently transferred to a cardiac referral centre for definitive management. He remained well during follow-up in the cardiac centre at nine months from initial presentation. Echocardiogram showed that the vegetation on mitral valve had resolved with residual moderate mitral regurgitation and left ventricular ejection fraction of 66.5%. He remained in Modified Rankin Score of 2.

Discussion

Majority of the melioidosis cases are presented with bacteraemia and pneumonia is a common presentation.2 Cardiac involvement is very rare. A prospective study on melioidosis in Darwin reported pericarditis in only 4 out of 540 cases.2 As well, melioidosis pericardial effusion was reported in around 1–3% of the total cases in previous studies.9,10 A defective native heart valve, however, is a predisposition for infective endocarditis.6 And B. pseudomallei was recently found to cause infective endocarditis.4,5

This case illustrates that of a young man, with no known medical illness, who presented with disseminated melioidosis but, which was complicated with infective endocarditis and cerebral infarct. The diagnosis of infective endocarditis was unexpected because the patient was initially sedated and ventilated. Infective endocarditis was only discovered upon cessation of sedative medications, when he was found to have hemiparesis. A possible septic embolus was suspected. This led to the discovery of the prolapsed mitral valve, which had a vegetation. Infective endocarditis was complicated with septic emboli to the brain. This resulted in cerebral infarct and haemorrhages as seen in this case.

Gentamicin is not used for treatment of melioidosis because B. pseudomallei is intrinsically resistant to penicillin, first and second-generation cephalosporin, aminoglycosides, and macrolides.3,11 However, this patient was infected by the gentamicin-susceptible B. pseudomallei strain. Therefore, we decided to use the combination of ceftazidime and gentamicin for the treatment of infective endocarditis in this patient. This was based on the experience of the synergistic effect of cephalosporins and aminoglycosides in the treatment of infective endocarditis. There are currently no guidelines on the treatment of melioidosis infective endocarditis. The identification of the specific aetiologic organism of infective endocarditis was important for the appropriate antibiotic therapy. In managing this case, we used 6 weeks of intensive phase antibiotics in the treatment of melioidosis, which was also consistent with the duration of treatment of infective endocarditis.

Conclusion

Melioidosis infective endocarditis is rare and reaching a diagnosis can be difficult. The intensive phase of melioidosis treatment must coincide with the duration of treatment of infective endocarditis. This would require clinical judgement, which would be guided by the patient’s clinical response and blood culture results. The use of gentamicin in the intensive phase of treatment for the gentamicin-susceptible B. pseudomallei strain requires further study.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Chua Hock Hin and Prof. Bart Currie for their advice and input in managing this case. We thank Dr Andrew Aeria for language editing. We also acknowledge the contributions of our colleagues from the ICU, medical, laboratory, and radiology teams in the management of this case.

Funding

This work is supported partly by the Ministry of Higher Education under the Research Acculturation Collaborative Effort Grant Scheme [RACE/b(2)/1246/2015(02))] and partly by our own operational funds.

Consent: The author/s confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including image(s) and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Authors' contributions: T.S. was responsible for patient management and this case write-up. T.B. provided radiology support, i.e. selecting images and providing related explanations. Y.P. was responsible for laboratory confirmation of the isolates. T.S., Y.P. and J.W. jointly prepared and compiled the facts of this case.

References

- 1. Limmathurotsakul D, Golding N, Dance DA, Messina JP, Pigott DM, Moyes CL, Rolim DB, Bertherat E, Day NP, Peacock SJ, Hay SI.. Predicted global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and burden of melioidosis. Nat Microbiol 2016;1:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Currie BJ, Ward L, Cheng AC.. The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis: 540 cases from the 20 Year Darwin prospective study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010;4:e900.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Podin Y, Sarovich DS, Price EP, Kaestli M, Mayo M, Hii K, Ngian H, Wong S, Wong I, Wong J, Mohan A, Ooi M, Fam T, Wong J, Tuanyok A, Keim P, Giffard PM, Currie BJ.. Burkholderia pseudomallei isolates from Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, are predominantly susceptible to aminoglycosides and macrolides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014;58:162–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mansoor CA, Jemshad A.. Melioidosis with endocarditis and massive cerebral infarct. Ital J Med 2015;10:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Piyasiri LB, Wickramasinghe SA, Lekamvasam VC, Corea EM, Gunarathne R, Priyadarshana U.. Endocarditis in melioidosis. Ceylon Med J 2016;61:192–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kandavello G, Adnan A, Chan JKM, Peariasmy KM, Arumugam K, Leong CL. et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and management of infective endocarditis. Putrajaya: Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2017.

- 7. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC.. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315: 801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Novak RT, Glass MB, Gee JE, Gal D, Mayo MJ, Currie BJ, Wilkins PP.. Development and evaluation of a real-time PCR assay targeting the type III secretion system of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schultze D, Muller B, Bruderer T, Dollenmaier G, Riehm JM, Boggian K.. A traveller presenting with severe melioidosis complicated by a pericardial effusion: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:242.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chetchotisakd P, Anunnatsiri S, Kiatchoosakun S, Kularbkaew C.. Melioidosis pericarditis mimicking tuberculous pericarditis. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:e46–e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Currie BJ. Melioidosis: evolving concepts in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015;36: 111–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]