Abstract

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are a subset of cancer cells that are shed from the primary or metastatic tumors into the bloodstream. CTCs are responsible for the establishment of blood-borne distant metastases but their rarity, estimated at one CTC per billion blood cells, presents the biggest technical barrier to their functional studies. Recent advances in CTC isolation technology have allowed for the reliable capture of CTCs from the whole blood of cancer patients. The ability to derive clinically relevant information from CTCs isolated through a blood draw allows for the monitoring of active disease, avoiding the invasiveness inherent to traditional biopsy techniques. This review will summarize recent developments in CTC isolation technology; the development of CTC-derived models; the unique molecular characteristics of CTCs at the transcriptomic, genomic, and proteomic levels; and how these characteristics have been correlated to prognosis and therapeutic efficacy. Finally, we will summarize the recent findings on several signaling pathways in CTCs and metastasis. The study of CTCs is central to understanding cancer biology and promises a “liquid biopsy” that can monitor disease status and guide therapeutic management in real time.

Introduction

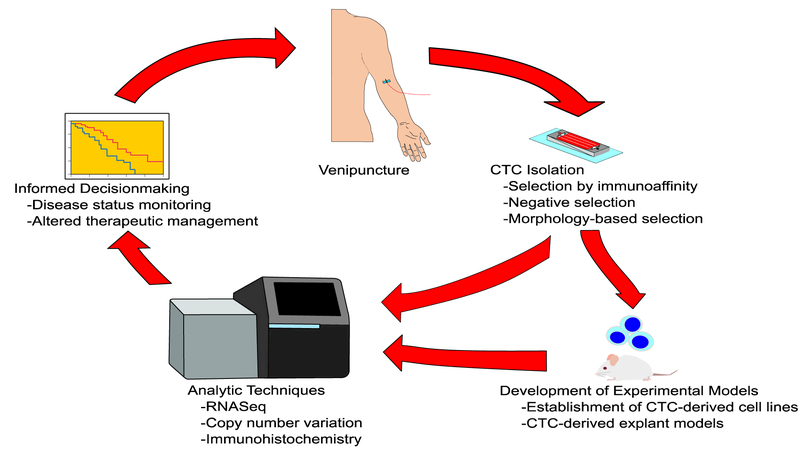

As a complex multi-step event that enables the primary tumor to spread and colonize other parts of the body, metastasis contributes up to 90% of cancer-related mortality.1 Metastasis requires the primary tumor cells to invade surrounding tissue, intravasate, transit while surviving anoikis, extravasate into tissues different from the original site, and adapt to the new microenvironment in a way that enables the formation of a macroscopic tumor.2–4 Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are directly involved in the metastatic process, presenting a unique opportunity to study cancer metastasis and progression. Additionally, clinicians can access CTCs through a blood draw, raising the possibility of utilizing CTCs as a “liquid biopsy” to determine prognosis or monitor therapeutic response.5–7 However, the prevalence of CTCs is estimated to be as low as 0–10 cells per 10mLs of blood in patients with metastatic disease, making their rarity the biggest challenge to isolation.8 Despite this, novel experimental models to amplify these rare cells and newly refined analytic techniques have begun to shed light on the unique properties of CTCs. These measurable properties must be correlated with clinical outcomes before CTCs can be used as a “liquid biopsy” to monitor disease status and inform clinical management (Figure 1). This review will focus on recent insights into CTC biology that inform our understanding of the metastatic process and the unique role CTCs play in cancer progression.

Figure 1.

Illustration of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) as a “liquid biopsy” for cancer patients. CTCs obtained from venipuncture are purified through 1 or several isolation techniques. These cells can be further amplified through the development of experimental models or analyzed directly through techniques requiring very little input material. Properties of CTCs at the genomic, transcriptome, or proteomic level can then be correlated to clinical outcomes either through overall survival or predicting therapeutic prognosis. This information can alter medical management with the process repeated at a future point in time. The current ability to do this is limited by the lack of understanding of the mechanistic role of CTCs in cancer progression. However, using serial CTC isolations as a “liquid biopsy” is predicted to become increasingly prevalent in guiding patient care and management.

CTC Isolation

The greatest technical challenge in capturing and studying CTCs is their rarity: it is estimated to be approximately 1 CTC per billion blood cells. CTC capture technologies have overcome this by exploiting the properties of CTCs that are distinct from other blood cells. Currently, the most commonly used technology is the CellSearch platform by Veridex, which is an immunoaffinity-based assay that isolates CTCs by positively selecting for an epithelial cell surface marker—specifically, epithelial cell adhesion marker (EpCAM). Captured cells can then be immunostained to confirm epithelial origin, verifying that they are positive for the epithelial marker cytokeratin (CK) and negative for the leukocyte marker CD45. The majority of competing CTC isolation technologies also rely on EpCAM and CK staining. Because of these techniques, the majority of CTC research exclusively involves EpCAM-positive cells.

EpCAM is prevalent in CTCs with epithelial characteristics but it is not a universal CTC biomarker. CTCs that have undergone epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and CTCs of mesenchymal origin can be EpCAM-negative.9 Additionally, cancer cell lines and CTCs isolated from patients have shown a wide range of EpCAM expression, with a portion of these cells being EpCAM-negative.10–12 Some technologies have tried to avoid biasing capture towards EpCAM-positive CTCs by removing CD45+ leukocytes, a process of negative selection, but these technologies suffer from low purity. Other negative selection technologies have relied on the unique mechanical properties of CTCs conferred by their greater nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, larger size, and abnormal nuclear morphology. These technologies have isolated CTCs based on cytoskeletal stiffness (which is potentially important in extravasation), density gradient centrifugation, porous microfiltration (which differentiates cells by size), and dielectrophoresis (which separates cells based on polarizability).9 However, these technologies lack specificity, which is particularly problematic when seeking out rare cell populations. For example, obtaining a purity of 99.9% in a sample with 1 rare cell per billion background cells still leaves a background of 1 million cells per desired cell. The technology continues to mature with increasing rates of capture and enrichment but CTC rarity remains the biggest barrier to studying the biology of these cells.

Models for Studying CTCs

To circumvent the limitations imposed by rarity several groups have attempted to develop additional models to study CTCs. One group implanted CTCs isolated from patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) into the flanks of immunodeficient mice to generate CTC-derived xenograft (CDX) models. Similar to patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models with tumor tissues, these CDX models can serve as avatars to monitor treatment responses for corresponding patients. Because of the availability of CTCs through a relatively non-invasive venipuncture, these models are particularly useful for aggressive SCLC, in which traditional biopsies are less commonly performed. It was also found that the number of CTCs correlated with time to palpable tumor in CDX models and that CDX tumors derived from chemorefractory disease had shorter doubling times than those from chemosensitive disease. Additionally, 3 CDX models treated with either cisplatin or etoposide showed a spectrum of therapeutic response to therapy with tumor growth correlating with survival times of corresponding patients, underscoring the potential clinical utility of these models.13

However, in some cases, there was genetic discordance between the CDX model and the corresponding patient. In 1 model, 2 CDX mice were generated with CTCs xenografted into their flanks. Although CTCs and CDX tumors from the same patient showed a strong correlation in copy number alterations (CNAs), 1 mouse showed a loss of chromosome arm 2p, which contains MYCN, and gain of BCL2 and SOX2 that were not present in the contralateral flank tumor. The second mouse showed an additional alteration of BCL2 not present in the contralateral tumor. Additionally, a c.440T>G mutation in TP53 was present in 1 patient’s tumor and CTCs, but not in the xenografted tumor.

An additional model of study is CTC-derived cell lines. Zhang et al. isolated EGFR+/HPSE+/ALDH1+ cells from the peripheral blood and established CTC-derived lines from 3 patients with breast cancer that had metastasized to the brain.14 We reported the establishment of CTC lines from 6 patients with metastatic ER+ breast cancer. Importantly, these lines were not selected from EpCAM+ cells and are grown in nonadherent culture with physiological oxygen levels that mimic in vivo conditions.15 A third group was also able to establish an EpCAM+ CTC line from a patient with chemotherapy-naïve metastatic colorectal cancer.16 These CTC-derived lines will be critical in performing detailed functional studies of these rare cells.

CTC Enumeration

CTC Enumeration Parallels Disease Course

Of all CTC isolation technologies, CellSearch is the only platform approved for prognostic use by the FDA, with the presence of 5 or more CTCs per 7.5mLs of blood serving as a negative prognostic indicator of progression-free survival and overall survival in metastatic breast, prostate, and colon cancer.12,17,18 Although FDA approval does not extend beyond prognosis, several studies have examined the utility of CTC enumeration in monitoring disease status. In the case of prostate cancer, serial measurement of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) remains the gold standard for detecting treatment failure.19 Comparing PSA levels to CTC enumeration longitudinally, Stott et al. found CTC enumeration tightly correlated with PSA measurements in 6 treatment-naïve metastatic prostate cancer patients after treatment with gonadotropin-receptor agonist leuprolide.20 Three patients, who were later found to be castration-resistant through a rise in PSA, showed a coincident rise in CTCs and a coincident decrease in both PSA and CTCs after treatment was switched to second-line agent docetaxel. One patient, who had disease progression while on leuprolide, showed a coincident increase in PSA and CTCs with both measures decreasing after adding bicalutamide to the treatment regimen. In all 6 cases, serial enumeration of CTCs closely paralleled measurements of serum PSA with both measurements correlating with disease status during treatment.

CTC Heterogeneity

The CellSearch platform has been widely used to enumerate CTCs but utilizing CTCs as a “liquid biopsy” requires analysis beyond enumeration. Emerging techniques have shown CTCs respond rapidly to changes in disease status due to their short lifespan of less than 24 hours, estimated by rapid decline after resection of localized prostate cancer.20 Additionally, 2 separate studies applying single cell RNA-seq to CTCs showed 45-60% have RNA with sufficient integrity to be sequenced.21,22 Taken together, these findings demonstrate the relatively rapid response of CTCs to changes in disease status as well as the ability to analyze these cells after isolation.

Analysis of CTC Heterogeneity

The rarity of CTCs raises the question as to whether isolating such a small subset of cells can accurately reflect disease status as a whole.23 In a patient with lung adenocarcinoma, one study investigated the concordance of genetic mutations between CTCs and primary or metastatic tumor populations using next-generation sequencing in matched biopsy samples from the primary tumor, a metastatic tumor in the liver, and 8 isolated CTCs. The investigators detected the same 4 mutations (EGFR, PIK3CA, RB1, TP53) across these tumor sources but only 1 mutation, EGFR, was in high abundance in the primary tumor.24 The remaining 3 mutations were initially missed by next-generation sequencing techniques and later found by PCR amplification, suggesting that these mutations are enriched in CTCs and metastases. A second study looking at the concordance between the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion locus—the most common molecular subtype of prostate cancer—found a 60-70% concordance between primary tumors and isolated CTCs, depending on whether the samples were analyzed by FISH or RT-PCR.25 A third study found that EGFR mutations were 74% concordant between matched primary tumors and CTCs in 21 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).26 Taken together, these studies showed a similar level of concordance between mutations found in CTCs and tumor populations.

Two studies showed an even higher concordance of CNAs between CTCs. Ni et al. found an average of 83% concordance in CNAs between any 2 CTCs among 8 CTCs of 1 patient with lung adenocarcinoma.27 A second study found an overall concordance of 82% between CTCs in CNAs when examining 31 patients with chemotherapy-naïve SCLC.28

CTC morphological heterogeneity also correlated with differences in the CTC transcriptome. In 1 study, Aceto and colleagues showed that inoculating mice with clusters of breast cancer cell lines resulted in significantly higher lung metastatic signal compared to inoculating with an equal number of single cancer cells. In addition, CTC clusters isolated from breast cancer patients expressed much higher levels of plakoglobin than single CTCs and plakoglobin knockdown reduced cluster formation and lung metastases in breast cancer cell lines.29 In a separate study using the KPC mouse model, which spontaneously develops pancreatic cancer, CTC clusters were found to be ~50 times more efficient in forming metastases than CTCs circulating as single cells.29,30 The CTCs in these clusters also showed similar transcriptomic heterogeneity to single cells isolated from the primary pancreatic cancer.22

CTC Heterogeneity Is Reflected in Disease Status

Although studies have shown that CTC enumeration can parallel the course of disease and that CTC heterogeneity can be reliably measured, utilizing CTCs as a “liquid biopsy” requires evaluating their ability to reflect disease status in response to treatment.31 In 1 study, 16 of 19 patients with ER+/HER2- breast cancer had detectable HER2 expression in their CTCs, despite the absence of HER2 amplification. After ex vivo culture, patient-derived CTC lines showed a bimodal distribution of HER2 expression. Following expansion in culture, FACS-sorted HER2+ or HER2- populations eventually reached a bimodal distribution approaching that of the parental lines, suggesting interconversion between HER2+ and HER2- cells. Mass spectrometry of the HER2+ and HER2- subpopulations showed increases in receptor tyrosine kinase expression and in Notch signaling, respectively. The HER2- subpopulation proliferated more slowly than did the HER2+ subpopulation, suggesting that the HER2- cells could serve as a reservoir of chemotherapy-resistant cells. This was validated when xenografted CTCs formed tumors that showed initial susceptibility to paclitaxel but rebounded in size 3 weeks after treatment withdrawal. In contrast, treating the same xenografted tumors with paclitaxel plus a Notch inhibitor showed a continued decline in tumor size after drug withdrawal.32

Carter et al. explored whether chemotherapeutic response can be predicted through genomic features of baseline CTCs isolated from patients with treatment-naive SCLC. Defining disease progression within 90 days of first-line therapy as chemorefractory, the authors sequenced a total of 72 single CTCs isolated at baseline from 6 chemorefractory patients and 7 chemosensitive patients. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the status of 13 genes known to be frequently amplified or deleted in SCLC did not show separation between CTCs from chemosensitive or chemorefractory patients. However, principal component analysis of CNA showed partial separation between the 2 groups, based on 16 CNA profiles. Applying these CNA profiles to 18 additional patients correctly classified them as chemosensitive or chemorefractory disease in 83% of cases. However, applying the same analysis to 46 CTCs from 5 initially chemosensitive patients after relapse only classified 6 of 46 CTCs correctly, suggesting that inherently chemorefractory SCLC and progressively chemorefractory SCLC involve fundamentally different mechanisms.28 In line with this finding, a separate study examined changes in SNV/INDEL status in CTCs isolated pre- and post-treatment and found increased mutations in 23 genes post-treatment. Gene ontology analysis identified 6 of the genes as belonging to the GO category “ATP binding”, although it was unclear how this pathway contributed to disease progression.27

Based on single cell RNA-seq analysis, Miyamoto and colleagues have found that CTCs, primary tumor samples, and individual cells from prostate cancer cell lines grouped into distinct clusters. Interestingly, individual CTCs from the same patient showed more heterogeneity than individual cells taken from established cell lines. Intrapatient CTC genetic heterogeneity was also seen in the T877A mutation of androgen receptor, present in 5 of 9 CTCs from the same patient. Comparing 41 CTCs from patients not treated with enzalutamide—a nonsteroidal antiandrogen used to treat castration-resistant prostate cancer—to 36 CTCs from patients with enzalutamide-resistant disease identified the enrichment of non-canonical Wnt signaling in the enzalutamide-resistant group.21 The phenotypic and transcriptional dynamics of CTCs in response to treatment was also detected in breast cancer patients based on the ratio of epithelial to mesenchymal transcripts.33 Taken together, these studies demonstrate that individual cancers with inherently different disease processes can be detected by analyzing changes in CTC genetics and expression.

Mechanistic Insights Derived from CTC analysis

Much of the literature on cancer has focused on classifying genes as either tumor suppressors or oncogenes based on their effect on tumor cell proliferation. However, metastasis is a complex process involving multiple aspects in addition to proliferation.34 Recently, several proliferating signaling pathways have been re-evaluated in the context of their metastatic involvement.

Wnt Signaling

The Wnt signaling pathway is well-known in tumorigenesis for its role in promoting cell proliferation and stemness. Aberrant Wnt signaling through either activation of positive regulators leading to constitutive pathway activation or loss-of-function mutations in Wnt signaling inhibitors are closely associated with carcinogenesis in breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancer.35–37 The loss of negative Wnt regulator APC is well-known for its role in familial adenomatous polyposis, an inherited syndrome predisposing patients to colorectal cancer, and roughly half of breast cancer cases are associated with aberrant Wnt signaling. 38,39 In agreement with this finding, non-canonical Wnt signaling was elevated in CTCs and metastasis in an engineered pancreatic cancer mouse model, and in CTCs isolated from castration-resistant prostate cancer patient.21,40

Despite the clear role of Wnt signaling in cancer progression, the role of DKK1—a negative regulator of Wnt—remains undefined.41,42 Unlike other negative regulators of Wnt signaling, loss-of-function mutations in DKK1 have been positively or negatively correlated with cancer progression in different studies.43–45 Several reviews have examined these disparities and failed to come to a consensus, concluding that DKK1’s role as tumor suppressor or oncogene may be dependent on context.46–48

Two recent studies evaluating DKK1’s role in cancer biology have recently shed light on this question by studying the effects of DKK1 unrelated to proliferation. Malladi et al. demonstrated that increased DKK1 allows 2 cell lines to enter a latent state in response to the stress of nutrient-poor media. DKK1 facilitates the evasion of innate immune surveillance by suppressing the expression of multiple natural killer cell activating ligands and inhibiting the migration of macrophages and granulocytes.49 Metastatic relapse after years or decades of latent tumor growth is a well-established phenomenon and upregulated DKK1 shows a plausible mechanism by which CTCs can enter a slow-growing state and avoid immune surveillance in disseminated organs.50,51

A second study by Zhuang et al. demonstrated how the microenvironment can modulate the differential effects of DKK1. Using breast cancer cell lines, the group showed DKK1 secretion by tumor cells suppressed metastatic growth in the lung but promoted growth in the bone. Intriguingly, the group also showed these results were accomplished by growth factor transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β). DKK1 secretion by tumor cells in the lung decreased tumor growth by decreasing the amount of bioavailable TGF-β but DKK1 secretion by tumor cells in the bone stimulated osteoclast formation that released TGF-β from catabolized bone mineral cortex.52 Taken together, the studies by Malladi et al. and Zhuang et al. demonstrate a complex picture for how DKK1 can convey advantages to tumor cells unrelated to proliferation and how this protein’s interaction with the microenvironment can affect organotropism.53–55

TGF-β Signaling

TGF-β is another signaling molecule that has been paradoxically described as enabling or inhibiting cancer progression, depending on timing and context. TGF-β is a signaling protein that binds to serine-threonine kinase receptors. One arm of the pathway activates members of the SMAD family, which are signal transducers known to suppress growth. A second arm activates death-associated protein 6 (DAXX), which activates the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway and induces apoptosis. Because of these effects, TGF-β is considered a tumor suppressor in early cancer progression but has been described as a permissive signal in late cancer progression.56 TGF-β is involved in many tissue types and activates or inhibits a large number of downstream transcripts. The transcripts regulated by TGF-β signaling are dependent on cellular context and epigenetic state. The discrepancy between TGF-β’s role in suppressing cancer progression early in the disease and later enabling progression has been proposed to be mediated by the loss of certain pathways and the enabling of others.57

In support of this, microarray analysis by Padua et al. found an association between TGF-β expression and lung metastasis in ER- breast cancers. This effect was found to be mediated by increased angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) expression, which facilitated invasion into the lung parenchyma through increased lung capillary permeability. This effect was found to be specific to lung metastasis while bone metastasis was unaffected by increased TGF-β expression. This organotropic effect was hypothesized to occur because of inherent differences in the bone architecture, which already contains discontinuous capillary channels.58 The study by Zhang et al. discussed earlier showed that tumor cells in the lung did not alter their expression of TGF-β but were able to alter its bioavailability by interacting with the lung and bone microenvironments.52 Taken together, these two studies demonstrate complex interactions between tumor cells and the microenvironment that affect how tumor cells respond to TGF-β in different contexts.

Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a highly conserved process that allows for increased migration and invasion. Developmentally, epithelial trophoblasts undergo EMT in order to invade the endometrium and initiate the formation of the placenta, and epithelial neuroectoderm cells undergo EMT to generate migratory neural crest cells. In wound healing, epithelial keratinocytes undergo EMT at the wound border and then revert via mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) for wound closure.59 EMT has been proposed as a mechanism by which cancer cells acquire properties required for intravasation and colonization of distant metastatic sites.

Studies of EMT have been limited by its inherent plasticity because cells that have undergone EMT are histologically indistinguishable from surrounding stroma. Additionally, most mesenchymal markers are intracellular, which limits isolation and immunoaffinity-based sorting.60 To get around this, several animal models have been developed that allow for lineage tracing by stably expressing fluorescent proteins in cancer cells that have undergone EMT.61,62 Previous studies had shown inducing EMT in cell culture allowed for increased invasiveness to the brain and lung but recent studies have questioned the necessity of EMT for cancer progression.14 Inhibiting EMT did not impact metastasis to the lung in one animal model of breast adenocarcinoma nor metastatic development in another mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.62,63 However, a study by Rhim et al. showed cancer cells can undergo EMT and seed distant organs before gross development of the primary tumor in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer.64 Furthermore, a recent study by Pastushenko et al. was able to identify cell populations undergo different states of EMT process and demonstrate their phenotypic differences in the metastatic cascade.65 Taken together, these studies have demonstrated the plasticity of EMT and the complexity in its role in cancer progression in animal models, which will require detailed investigation in various contexts of human cancers.

Although EMT is being highly debated for its necessity in metastasis initiation, a handful of studies have shown it may be involved in conferring therapeutic resistance. We have found an increase in CTCs with mesenchymal markers in cases where breast cancer was associated with treatment resistance, a finding which was corroborated by animal studies demonstrating similarly decreased sensitization of EMT-derived lineages to chemotherapy.33,62,63 Specific mechanisms by which this occurs have not been elucidated but the slower cycling rate conferred by a mesenchymal phenotype may explain resistance to chemotherapy, which is more effective against actively proliferating cells.32,49 Although no coherent theory has been universally accepted for the role of EMT in facilitating metastasis, its association with therapeutic resistance points to the importance in detecting EMT in CTCs as a liquid biopsy for the active tumors. Several studies have focused on characterizing EpCAM- cells that are absent for typical leukocyte markers in the blood stream. A study by Zhang et al. isolated EpCAM- CTCs and found that CTC lines derived from EpCAM- cells efficiently metastasized to the brain and lungs of immunodeficient mice.14

Summary

The study of CTCs has been challenging due to their extreme rarity and difficulty in isolation. Despite this, recent advances have enabled the understanding of CTC biology, which is central to fundamentally understanding the nature of cancer. Recent publications have demonstrated that CTCs can be used as a “liquid biopsy” to predict prognosis, monitor disease status, and inform therapeutic management. Outside of the clinical setting, studies on CTC biology have begun to shed light on the role of CTCs in cancer progression. Previously described pathways and processes such as Wnt signaling antagonist DKK1, TGF-β, and EMT are coopted during metastasis in order to facilitate cancer progression. These events are sensitive to microenvironmental contexts, have roles in facilitating immune evasion, and confer chemotherapeutic resistance in ways that are unique to CTCs. The understanding of CTCs is still in its infancy but elaborating their molecular properties that contribute to metastasis will be key to halting cancer progression.

Acknowledgments

Research in the M.Y. laboratories is funded by the NIH K22 award (K22 CA175228-01A1), NIH DP2 award (DP2 CA206653), Donald E. and Delia B. Baxter Foundation, Stop Cancer Foundation, Wright Foundation, and the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Alexander & Margaret Stewart Trust (Pew-Stewart Scholar for Cancer Research) to M.Y. We are grateful to Ms. C. Lytal for assisting us with the manuscript editing. We apologize to colleagues whose studies were not incorporated in this review due to space limitations.

Abbreviations:

- ANGPTL4

angiopoietin-like 4

- CDX

CTC-derived xenograft

- CK

Cytokeratin

- CNA

copy number alteration

- CTC

circulating tumor cell

- DAXX

death-associated protein 6

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- EpCAM

epithelial adhesion molecules

- INDEL

insertion/deletion

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinases

- MET

mesenchymal-epithelial transition

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- PDX

patient-derived xenograft

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- SCLC

small cell lung cancer

- SNV

single nucleotide variation

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor beta

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have read the journal’s policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest and have none to declare. All authors have read the journal’s authorship agreement.

References

- 1.Sporn MB. The War on Cancer. Lancet. 1996;347(9012):1377–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A Perspective on Cancer Cell Metastasis. Science. 2011;331(6024):1559–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanharanta S, Massague J. Origins of Metastatic Traits. Cancer Cell. 2013;24(4):410–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim M-Y, Oskarsson T, Acharyya S, et al. Tumor Self-seeding by Circulating Tumor Cells. Cell. 2009;139(7):1315–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alix-Panabieres C, Pantel K. Circulating Tumor Cells: Liquid Biopsy of Cancer. Clin Chem. 2013;59(1):110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bardelli A, Pantel K. Liquid Biopsies, What We Do Not Know (Yet). Cancer Cell. 2017;31(2):172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu M, Stott S, Toner M, Maheswaran S, Haber DA. Circulating Tumor Cells: Approaches to Isolation and Characterization. J Cell Biol. 2011:192(3):373–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Micalizzi DS, Maheswaran S, Haber DA. A Conduit to Metastasis: Circulating Tumor Cell Biology. Genes Dev. 2017;31(18):1827–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabriel MT, Calleja LR, Chalopin A, Ory B, Heymann D. Circulating Tumor Cells: A Review of Non-EpCAM-Based Approaches for Cell Enrichment and Isolation. Clin Chem. 2016:62(4):571–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Wit S, van Dalum G, Lenferink ATM, et al. The Detection of EpCAM+ and EpCAM-Circulating Tumor Cells. Sci Rep. 2015:5:12270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pantel K, Deneve E, Nocca D, et al. Circulating Epithelial Cells in Patients with Benign Colon Diseases. Clin Chem. 2012;58(5):936–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikolajczyk SD, Millar LS, Tsinberg P, et al. Detection of EpCAM-Negative and Cytokeratin-Negative Circulating Tumor Cells in Peripheral Blood. J Oncol. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodgkinson CL, Morrow CJ, Li Y, et al. Tumorigenicity and Genetic Profiling of Circulating Tumor Cells in Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Nat Med. 2014;20(8):897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Ridgway LD, Wetzel MA, et al. The Identification and Characterization of Breast Cancer CTCs Competent for Brain Metastasis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;10(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu M, Bardia A, Aceto N, et al. Ex Vivo Culture of Circulating Breast Tumor Cells for Individualized Testing of Drug Susceptibility. Science. 2014;345(6193):216–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cayrefourcq L, Mazard T, Joosse S, et al. Establishment and Characterization of a Cell Line from Human Circulating Colon Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75(5):892–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Bono JS, Scher HI, Montgomery RB, et al. Circulating Tumor Cells Predict Survival Benefits from Treatment in Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(9):6302–6309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giuliano M, Giordano A, Jackson S, et al. Circulating Tumor Cells as Early Predictors of Metastatic Spread in Breast Cancer Patients with Limited Metastatic Dissemination. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penson DF. Follow-up Surveillance During and After Treatment for Prostate Cancer. UpToDate. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stott SL, Lee RJ, Nagrath S, et al. Isolation and Characterization of Circulating Tumor Cells from Patients with Localized and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(25). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyamoto DT, Zheng Y, Wittner BS, et al. RNA-Seq of Single Prostate CTCs Implicates Noncanonical Wnt Signaling in Antiandrogen Resistance. Science. 2015;349(6254):1351–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ting DT, Wittner BS, Ligorio M, et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Identifies Extracellular Matrix Gene Expression by Pancreatic Circulating Tumor Cells. Cell Rep. 2014;8(6):1905–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Punnoose EA, Atwal SK, Spoerke JM, et al. Molecular Biomarker Analyses Using Circulating Tumor Cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomlin SA, Laxman B, Varambally S, et al. Role of the TMPRSS2-ERG Gene Fusion in Prostate Cancer. Neoplasia. 2008;10(2):177–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sundaresan TK, Sequist L V, Heymach J V, et al. Detection of T790M, the Acquired Resistance EGFR Mutation, by Tumor Biopsy versus Noninvasive Blood-Based Analyses. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(5):1103–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ni X, Zhou M, Su Z, et al. Reproducible Copy Number Variation Patterns among Single Circulating Tumor Cells of Lung Cancer Patients. PNAS. 2013;110(52):21083–21088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter L, Rothwell DG, Mesquita B, et al. Molecular Analysis of Circulating Tumor Cells Identifies Distinct Copy-Number Profiles in Patients with Chemosensitive and Chemorefractory Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Nat Med. 2016;23(1):114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aceto N, Bardia A, Miyamoto DT, et al. Circulating Tumor Cell Clusters are Oligoclonal Precursors of Breast Cancer Metastasis. Cell. 2014;158(5):1110–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maddipati R, Stanger BZ. Pancreatic Cancer Metastases Harbor Evidence of Polyclonality. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(10):1086–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cruz MR, Costa R, Cristofanilli M. The Truth is in the Blood: The Evolution of Liquid Biopsies in Breast Cancer Management. Asco Annu Meet. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordan NV, Bardia A, Wittner BS, et al. HER2 Expression Identifies Dynamic Functional States within Circulating Breast Cancer Cells. Nature. 2016;537:102–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu M, Bardia A, Wittner BS, et al. Circulating Breast Tumor Cells Exhibit Dynamic Changes in Epithelial and Mesenchymal Composition. Science. 2013:339(6119):580–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gospodarowicz M, O’Sullivan B. Prognostic Factors in Cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 2003;21(1):13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rapp J, Jaromi L, Kvell K, Miskei G, Pongracz JE. WNT Signaling - Lung Cancer is no Exception. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murillo-Garzón V, Kypta R. WNT Signalling in Prostate Cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14(11):683–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pohl S-G, Brook N, Agostino M, Arfuso F, Kumar AP, Dharmarajan A. Wnt Signaling in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Oncogenesis. 2017;6:e310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhan T, Rindtorff N, Boutros M. Wnt Signaling in Cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36(11):1461–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin S-Y, Xia W, Wang JC, et al. Beta-catenin, a Novel Prognostic Marker for Breast Cancer: its Roles in Cyclin D1 Expression and Cancer Progression. PNAS. 2000;97(8):4262–4266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu M, Ting DT, Stott S, et al. RNA Sequencing of Pancreatic Circulating Tumour Cells Implicates WNT Signalling in Metastasis. Nature. 2012;487(7408):510–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polakis P Wnt Signaling and Cancer. Genes Dev. 2000;14(15):1837–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polakis P Wnt Signaling in Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao YP, Wang W, Wang XH, et al. Downregulation of Serum DKK-1 Predicts Poor Prognosis in Patients with Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14(4):18886–18894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ko YB, Kim B-R, Yoon K, et al. WIF1 can Effectively Co-regulate Pro-apoptotic Activity through the Combination with DKK1. Cell Signal. 2014;26(11):2562–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du Q, Zhang X, Liu Q, Zhang X, Bartels CE, Geller DA. Nitric Oxide Production Upregulates Wnt/B-catenin Signaling by Inhibiting Dickkopf-1. Cancer Res. 2013;73(21):6526–6537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Menezes ME, Devine DJ, Shevde LA, Samant RS. Dickkopf1: A Tumor Suppressor or Metastasis Promoter? Int J Cancer. 2012;130(7):1477–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Rojo F, Munoz A. The Complex Life of DICKKOPF-1 in Cancer Cells. Cancer Cell Microenviron. 2015;2(3). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kagey MH, He X. Rationale for Targeting the Wnt Signalling Modulator Dickkopf-1 for Oncology. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174(24):4637–4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malladi S, Macalinao DG, Jin X, et al. Metastatic Latency and Immune Evasion through Autocrine Inhibition of WNT. Cell. 2016;165(1):45–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Braun S, Vogi F, Naume B, et al. A Pooled Analysis of Bone Marrow Micrometastasis in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(8):793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sosa MS, Bragado P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Mechanisms of Disseminated Cancer Cell Dormancy: An Awakening Field. Nat Rev. 2014;14(9):611–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhuang X, Zhang H, Li X, et al. Differential Effects on Lung and Bone Metastasis of Breast Cancer by Wnt Signalling Inhibitor DKK1. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19(10):1274–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meng S, Tripathy D, Frenkel EP, et al. Circulating Tumors Cells in Patients with Breast Cancer Dormancy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(24):8152–8162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fidler IJ. The Pathogenesis of Cancer Metastasis: the “Seed and Soil” Hypothesis Revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003:3,453–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duda DG, Duyverman AMMJ, Kohno M, et al. Malignant Cells Facilitate Lung Metastasis by Bringing their Own Soil. PNAS. 2010:107(50):21677–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Massague J TGFB Signalling in Context. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:616–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Massague J TGFB in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134(2):215–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Padua D, Zhang XH, Wang Q, et al. TGFB Primes Breast Tumors for Lung Metastasis Seeding through Angiopoietin-like 4. Cell. 2008;133(1):66–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heerboth S, Housman G, Leary M, et al. EMT and Tumor Metastasis. Clin Transl Med. 2015;4(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rhim AD. Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition and the Generation of Stem-like Cells in Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreatology. 2013;13(2):144–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aiello NM, Rhim AD, Stanger BZ. Isolating Epithelial and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Populations from Primary umors by Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2016:34–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fischer KR, Durrans A, Lee S, et al. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition is not Required for Lung Metastasis but Contributes to Chemoresistance. Nature. 2015;527(472–476). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng X, Carstens J, Kim J, et al. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition is Dispensable for Metastasis but Induces Chemoresistance in Pancreatic Cancer. Nature. 2015;527:525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rhim AD, Mirek ET, Aiello NM, et al. EMT and Dissemination Precede Pancreatic Tumor Formation. Cell. 2012;148(1–2):349–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pastushenko I, Brisebarre A, Sifrim A, et al. Identification of the Tumour Transition States Occuring During EMT. Nature. 2018; 556:463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]