Abstract

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) is a common problem for pregnant women. Researchers have recently paid special attention to complementary medicine methods for the treatment of NVP. Regarding the high prevalence of NVP as well as maternal and fetal adverse effects of chemical drugs, the present study, focusing on clinical trials carried out in Iran, was conducted to assess safety and efficacy of different nonpharmacological methods in relieving NVP. This systematic review focused on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and assessed complementary medicine on NVP for which databases including MedLib, Magiran, Iran Medex, SID, PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar search engines from 2000 to 2015 were searched. Those articles that gained score 3 or higher, according to Jadad criteria, were recruited for the study. In this study, 31 clinical trials assessing NVP were conducted on Iranian pregnant women. After removing ten articles, 21 articles with scores 3 and higher, according to Jedad criteria, were assessed. Out of 21 papers, 10 papers were about ginger, one was about cardamom, one was about lemon, two were about peppermint aromatherapy, six were about pericardium 6 (P6) acupressure, and one article about KID21 acupressure. Most studies have demonstrated a positive effect on reducing NVP; however, no adverse effect was reported. According to the results of this review, the majority of methods employed were effective in reducing the incidence of NVP, among which ginger and P6 acupressure can be recommended with more reliability.

Keywords: Clinical trial, complementary medicine, nausea, pregnancy, vomiting

Introduction

More than two-third of pregnant women suffer from nausea and vomiting;[1] it usually starts in weeks 6–8 of pregnancy and ends around week 12 although its symptoms may remain until week 20 in some women.[2] Half of the pregnant women usually suffer from nausea and vomiting and 25% suffer from only nausea.[3] Severe nausea and vomiting accompanied by symptoms including dehydration, acidosis, alkalosis, and weight loss threaten the mother's health.[4] The main cause of this common problem of pregnancy is unknown and is probably due to several factors among which hormonal changes have the most important role.[5] Although nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) is limited to the first trimester of pregnancy, a minimal percentage of cases continue until delivery.[6] NVP is accompanied by an increased risk of maternal stress, anxiety and depression,[7] low quality of life,[8] and reduction of maternal physical and social function.[9] The risk factors of NVP include race,[10] baby's sex,[11] young maternal age,[12] multifetal gestation, low income, low education level,[13] history of premenstrual syndrome, and unwanted pregnancy.[14] Complementary medicine has obtained special attention over the recent years.[15] Complementary medicine is based on ancient and natural remedies. Pregnant women are applying different methods of complementary medicine including aromatherapy, acupressure/acupuncture, herbs, homeopathy, and reflexology.[16] Different types of treatment are used for NVP.[17] Treatment of NVP depends on the severity of symptoms.[18] In addition to diet, therapy, and lifestyle modification, complementary medicine is an interesting complementary for many women[19] so that more than 87% of women use at least one method of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy.[20] Many pregnant women prefer complementary medicine, due to its lower adverse effects, to chemical drugs.[21] In a review, complementary and alternative therapies were more frequently used in pregnant women with higher education and a history of vaginal delivery.[22]

Iranian traditional medicine is a school of holistic medicine, special comments on diagnosis and treatment of diseases.[23]

Since review studies due to their precise and strict structure are considered a standard resource to establish healthcare-related evidence,[24] a systematic review is a “vital link” between research-based studies and clinical decision-making.[25] Indeed, considering the importance of maternal and fetal health and the side effects of chemical drugs as well as the need for effective treatment methods with minimal adverse effects, this study as a systematic review aimed to summarize the analysis of retrospective clinical trials carried out in Iran. Regarding the increasing demand for complementary medicine, this is the first systematic review in this field in Iran. This study aimed to review and summarize the analysis of clinical trials in this context and to assess safety and efficacy of different methods for relieving NVP in Iran.

Methods

Searching strategy

This study is a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), assessing all published Iranian articles (RCT) from 2000 to 2015 in Persian or English searched from Iranian databases including MedLib, Magiran, Iran Medex, SID, Scopus, and PubMed and Google Scholar search engines. The articles were searched with the following keywords: Nausea and vomiting, pregnancy, complementary medicine, and clinical trials. In this study, all clinical trials assessing NVP in Iran were recruited. In Scopus, the articles were limited to Iran, and in PubMed, the articles were limited to clinical trials in all databases, advance search was used.

Criteria for inclusion in this review

Selection of studies

Two authors reviewed the eligibility of trials, independently evaluated the risk of bias, and extracted the data for the included trials. Information on demographic characteristics of the study population during the study period, the number of patients in control group, duration of study, measurement tools, adverse effect of each intervention, and the number of affected participants who got better with treatment and placebo were extracted. All RCTs containing complementary medicine for treatment of NVP were included in the study, and all clinical trials employed one of the following standard tools to measure the severity of NVP: the Rhodes Index of Nausea and Vomiting, visual analog scale-McGill nausea questionnaire, and Pregnancy-Unique Quantification of Emesis and Nausea.

Types of participants

All clinical trials including healthy pregnant women who had experienced nausea with or without vomiting, with single fetus, and without any history of gastrointestinal diseases were assessed.

Types of interventions

The types of interventions used were all clinical trials including complementary medicine treatment versus placebo, no treatment, or any treatment for NVP.

Types of comparator/control

The types of comparator/control used were placebo and no treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Nausea and vomiting symptom scores were measured by standardized scales. The occurrence of adverse effects and side effects was recorded.

Risk of bias

Jadad criteria were used to evaluate the articles. This scale assesses the articles based on the probability of bias in randomization, the patients’ follow-up, and blinding. The overall score of this scale ranges from 0 to 5 where score 5 is the strongest methodologically.[26] According to these criteria, the articles with a score 3 or higher were included in the study. Searching in databases was performed by two authors; the abstracts were first assessed and then some articles were subjected to final assessment according to Jadad scale and inclusion criteria.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Shahid Beheshti Medical University (IR.SBMU.PHNM. 1395.629).

Results

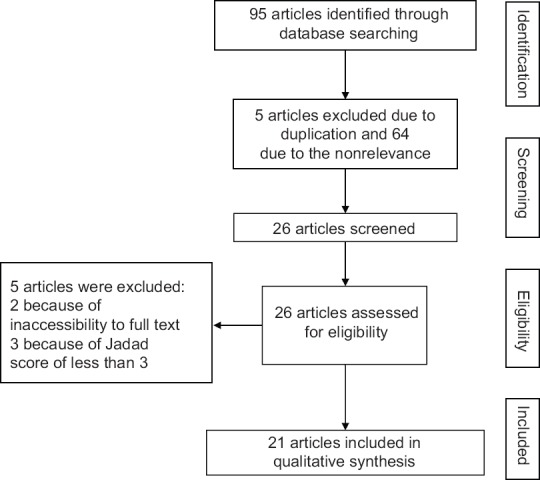

In this study, 95 clinical trials were recruited, and after eliminating 74 articles, 21 articles were eventually assessed: out of 21 articles, 10 papers were about ginger, one was about cardamom, three were about aromatherapy, six were about pericardium 6 (P6) acupressure, and one was about KID21 acupressure. Most studies have demonstrated a positive effect on reducing NVP; however, no adverse effect was reported.

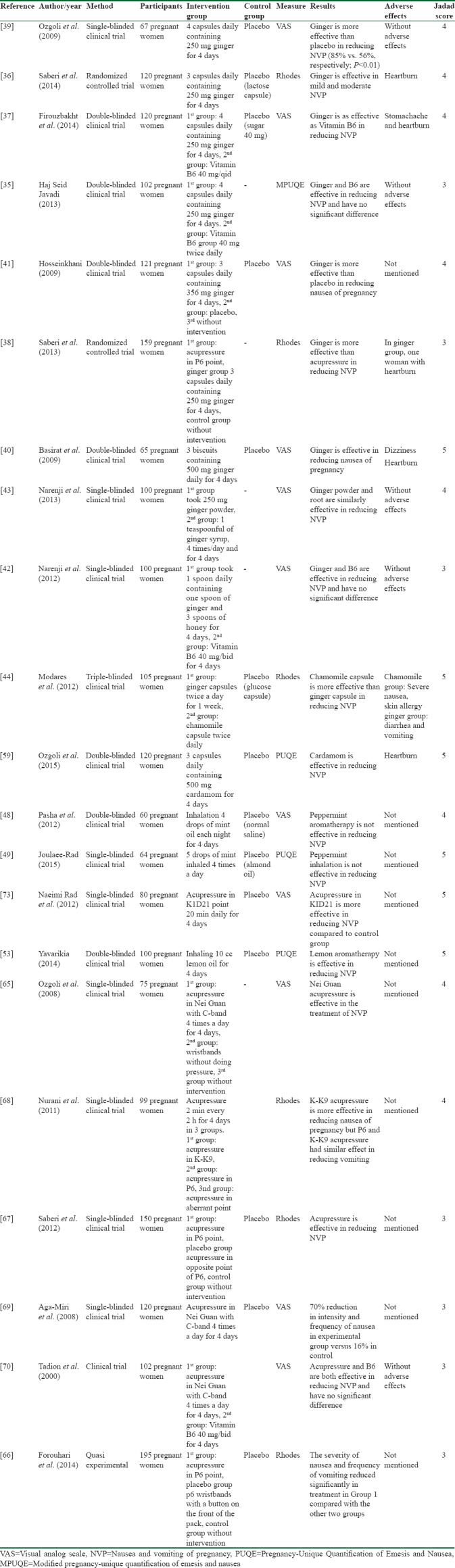

The evaluated studies are summarized in Table 1, and the assessed methods are described in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

Figure 1.

Flowchart of article selection

Ginger

Ginger is considered a medicinal herb used for the treatment of nausea of pregnancy, alleviation of joint pain, treatment of inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis,[27] improving the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome,[28] reducing nausea and vomiting after surgery,[29,30] and after chemotherapy.[31] Ginger's mechanism of action in reducing nausea and vomiting is unknown.[32] In this review, ten clinical trials with 1059 participants evaluated the effectiveness of ginger for NVP.

However, some studies have shown that ginger acts through antiserotonin-3 (5HT3).[33,34] Haji Seid Javadi et al. reported that ginger and Vitamin B6 are both effective in reducing NVP. Although the impact of Vitamin B6 was greater, there was no statistically significant difference.[35] Saberi et al. found that ginger capsules led to more significant mitigation of NVP compared to the control group and placebo.[36] Firouzbakht et al. found that ginger capsule was as effective as Vitamin B6 in alleviating NVP.[37] In another study, Saberi et al. demonstrated that ginger is more effective than acupressure in reducing NVP.[38] Ozgoli et al. showed that 1000 mg of daily ginger intake was more effective than placebo in reducing NVP (85% vs. 56%, respectively; P < 0.01).[39] Basirat et al. (2009) demonstrated a significant decrease in nausea of pregnancy in the study group receiving ginger biscuits, but there was no significant reduction in vomiting of pregnancy in the ginger group.[40] Hosseinkhani and Sadeghi found ginger capsules to be effective in reducing nausea of pregnancy.[41] Narenji et al. (2012) demonstrated that ginger root syrup was almost as effective as Vitamin B6 in reducing NVP.[42] Likewise, Narenji et al. found that ginger root and powder were similarly effective in the alleviation of NVP.[43] Modares et al. found that chamomile oral capsules are more effective in reducing the symptoms of NVP compared to ginger and placebo.[44]

Peppermint aromatherapy

Mint is a well-known and important medicinal herb that is used as a reducer of postoperative nausea as well as an antiseptic, analgesic, and anticlotting agent in medicine.[45] One proposed mechanism for its anti-emetic and anti-spasmodic effects on the gastrointestinal system is inhibition of serotonin-induced muscle contractions.[46] Peppermint also acts as an anesthetic on the stomach wall that stops nausea and vomiting.[47] In this review, two studies with 124 participants evaluating the effectiveness of peppermint for NVP were reviewed. In a study conducted by Pasha et al., aromatherapy with peppermint oil caused no significant reduction in NVP compared to the placebo (normal saline).[48] Furthermore, Joulaee Rad found that inhaled peppermint had no effect on reducing the severity of NVP, compared to almond oil (placebo).[49]

Lemon aromatherapy

Aromatherapy is a complementary medicine which using inhaled essences for treatment of disease.[50] Lemon is rich in phenolic compounds, vitamins, minerals, fiber, and carotenoid oil[51] and has analgesic, antiseptic, anti-emetic, and diuretic properties.[52] In a study by Yavari-Kia et al. (2014), lemon aromatherapy led to a significant reduction in NVP compared to placebo.[53]

Cardamom

Cardamom is a fragrant herb with a long history in the treatment of gastrointestinal symptoms and stomach pain. The oil extracted from cardamom seeds is a combination of terpenes, esters, flavonoids, and other compounds.[54] This herb has medical benefits for asthma treatment[55] and it has anti-hyperlipidemic,[56] anti-septic, anti-spasmodic, anti-bloating, and diuretic properties.[57] Aromatherapy with inhalation of cardamom oils is effective in relieving nausea caused by chemotherapy in patients with cancer.[58] Ozgoli et al. (2015) demonstrated that intake of capsules containing 500 mg cardamom powder three times a day significantly reduced the severity of NVP.[59]

Pericardium 6 (Nei Guan)

Acupressure is a nonmedicinal method for reducing nausea and vomiting.[60] Acupressure in C-band area is an effective, safe, and inexpensive method for mitigating NVP.[61] Acupressure in P6 point which is two-thumb width above the distal crease of the internal wrist has long been used in the treatment of NVP, postoperative nausea, and chemotherapy-induced nausea.[62] The mechanism of acupressure is unknown, but low-frequency transcutaneous stimulation may change the transmission of neurotransmitters.[63] Acupressure also has an inhibitory effect on the secretion of gastric acids.[64] In a study conducted by Ozgoli et al., a wristband with a button was more effective than placebo in alleviating the severity of nausea and was more effective than control group in reducing the frequency of vomiting; however the wristband, compared to placebo, was not effective in reducing the frequency of vomiting.[65] Forouhari et al. (2014) concluded that P6 acupressure caused a significant reduction in severity and frequency of NVP.[66] Saberi et al. demonstrated that P6 acupressure is an effective treatment for NVP and the difference was not significant between placebo and P6 acupressure.[67] Nurani et al. also suggested that K-K9 acupressure (in the second phalanx of ring finger) was more effective in reducing nausea during pregnancy, but it had similar effects as P6 acupressure in reducing vomiting of pregnancy.[68] Aga-Miri et al. demonstrated that acupressure in Nei Guan point reduced the frequency and severity of nausea by 70%.[69] In a study conducted by Tadion et al., acupressure in Nei Guan point and Vitamin B6 were equally effective in reducing NVP.[70]

Acupressure in KID21 point

Acupressure as a nonmedicinal method is effective in reducing nausea and vomiting after surgery[71] and chemotherapy.[72] KID21 is the distance of 2 cuns below the sternocostal angle and 0.5 cuns lateral to mid anterior in the abdominal area. Naeimi Rad et al. showed that acupressure in KID21 area is more effective than placebo (shame acupressure) in reducing NVP in pregnant women.[73]

Discussion

This review was intended to assess the effects of complementary medicine on NVP. Twenty-one clinical trials with 2004 participants were included in this review. Different types of intervention such as acupressure, aromatherapy, and herbal medicine have been used in these studies. Twenty-one studies took 3–5 scores of Jadad scale. Jadad criteria such as the randomization, blinding, follow-up concealment allocation, intention to treat[26] were used in evaluating all the respective articles.

Ten articles were dedicated to the effects of ginger and six to the impacts of Nei Guan acupressure. Cochrane's reviews found that ginger and acupressure can reduce nausea of pregnancy without adverse effects.[74] Other meta-analyses have also supported the safe effectiveness of ginger on NVP.[32,75] The exact mechanism of ginger in reducing NVP is unknown,[76] but ginger-containing compounds such as 6-gingerol, 6-shogaol, and galano-lactogen have antiserotonin-3 (5HT3) effects.[77] Moreover, ginger has central anti-emetic and anticholinergic properties.[78,79] The recommended dose of ginger in most studies is 250 mg every 4 h and the side effects of this herb are unknown although it may cause heartburn, diarrhea, and fibrinolysis.[76] In our review, different forms of ginger such as capsule, syrup, and biscuit have been compared versus placebo or anti-emetic drug, and the side effects of using this intervention have been mentioned. In clinical consultations for the management of NVP, it is very important to address the potential harms and benefits of ginger.[80]

Six articles have examined the effect of P6 acupressure on NVP. The exact mechanism of acupressure effect on preventing from NVP is unknown, but studies have shown that concentration of β-endorphin increases in cerebrospinal fluid after acupressure which has anti-emetic effect.[81,82] In addition, P6 stimulation reduces nausea and vomiting by increasing blood flow and stabilizing the brain cortex[83] and also increases the regular gastrointestinal myoelectrical activity.[84] A systematic review conducted by Van den Heuvel et al. reviewed RCT studies on the efficacy of different techniques of acupoint stimulation in pregnant women for treatment of NPV or hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) and their studies did not show any evidence of symptoms alleviation in NVP and HG.[85] Matthews et al. (2014) reviewed different interventions for nausea and vomiting such as acupressure, acustimulation, acupuncture, ginger, and Vitamin B6 in early pregnancy as previously published in 2003 and reported no significant effect of P6 or traditional acupuncture in pregnant women with nausea and vomiting and also presented limited evidence on the effectiveness of ginger.[86] However, the results presented by Lete and Allué demonstrated that ginger was used as an effective treatment for nausea and vomiting of early pregnancy.[87] Only one study examined each on cardamom, lemon, and KID21 acupressure and two studies examined peppermint aromatherapy. Although the results of most studies were positive and these methods were effective in reducing NVP, more research in this field is required. Regarding safety, more clinical trials are needed to evaluate their side effects. The results of this study can improve the quality of health services and health problem-solving in pregnant women. In general, to provide sufficient evidence on the effects of complementary medicine, high-quality methodological studies are needed. It is hoped that further studies with high methodological quality can establish a protocol about the effectiveness of complementary medicine in the treatment of NVP to use health-care team, including physicians, gynecologists, and midwives provided.

Limitation

There are a few limitations in our systematic review; one limitation is related to variability in dosage and duration of treatment, another limitation concerns differences in the formulation of some treatment methods such as different forms of ginger including syrup, biscuit, and capsules. Another limitation of this study is that, since a scanty number of studies have been conducted on some types of interventions such as aromatherapy and acupressure, along with inconsistency of studies, it was impossible to perform meta-analysis. Another limitation of this study was that there was no possibility to search in gray literature. The strength of this study is that this is the first systematic review of clinical trials about the effects of complementary medicine on NVP carried out in Iran.

Conclusions

Some types of complementary medicine are commonly consumed in our life. According to results of the review, most methods were effective in reducing the incidence of NVP, among which ginger and P6 acupressure can be recommended more confidently. In addition, regarding our systematic review, we concluded that complementary medicine is an effective nonpharmacological option for improving NVP with respect to the inherent inconsistency of available literature.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Herrell HE. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:965–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarvis S, Nelson-Piercy C. Management of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. BMJ. 2011;342:d3606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krzyscin M, Grzymislawski M, Dera A, Breborowicz G. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Arch Perinat Med. 2009;15:209–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mylonas I, Gingelmaier A, Kainer F. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Dtsch Arztebl. 2007;104:1821–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor T. Treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Indep Rev. 2014;37:42–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee NM, Saha S. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40:309–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.03.009. vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer J, Bowen A, Stewart N, Muhajarine N. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: Prevalence, severity and relation to psychosocial health. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2013;38:21–7. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e3182748489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attard CL, Kohli MA, Coleman S, Bradley C, Hux M, Atanackovic G, et al. The burden of illness of severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:S220–7. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith C, Crowther C, Beilby J, Dandeaux J. The impact of nausea and vomiting on women: A burden of early pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;40:397–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.2000.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lacasse A, Rey E, Ferreira E, Morin C, Bérard A. Epidemiology of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: Prevalence, severity, determinants, and the importance of race/ethnicity. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tezerjani FZ, Sekhavat L. Relationship between fetal sex and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. World Appl Sci J. 2013;28:1024–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Källén B, Lundberg G, Aberg A. Relationship between vitamin use, smoking, and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:916–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louik C, Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: Maternal characteristics and risk factors. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20:270–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soltani A, Kajuri MD, Safavi S, Hosseini F. Frequency and severity of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and the related factors among pregnant women. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 07];Iran J Nurs. 2007 19:95–102. Available from: http://ijn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-222-en.html or http://ijn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-222-en.html . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams J, Lui C, Sibbritt D, Broom A, Wardle J, Homer C. Women's use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy: A critical review of the literature. Birth. 2009;36:237–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bishop J, Northstone K, Green J, Thompson E. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in pregnancy: Data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) Complement Ther Med. 2011;19:303–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babaei AH, Foghaha MH. A randomized comparison of Vitamin B6 and dimenhydrinate in the treatment of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19:199–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith J, Refuerzo J, Ramin S. Treatment of Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy (Hyperemesis Gravidarum and Morning Sickness) Document consulté le. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollyer T, Boon H, Georgousis A, Smith M, Einarson A. The use of CAM by women suffering from nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2002;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frawley J, Adams J, Broom A, Steel A, Gallois C, Sibbritt D, et al. Majority of women are influenced by nonprofessional information sources when deciding to consult a complementary and alternative medicine practitioner during pregnancy. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:571–7. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abedzadeh Kalahroudi M. Complementary and alternative medicine in midwifery. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2014;3:e19449. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strouss L, Mackley A, Guillen U, Paul DA, Locke R. Complementary and alternative medicine use in women during pregnancy: Do their healthcare providers know? BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:85. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jafari-dehkordi E, Sohrabvand F, Nazem E, Minaee B, Hashem-Dabagian F, Sadegpor O, et al. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and an overview of the causes and treatments of traditional medicine in Iran. Open J Obstetrics Gynecol. 2013;5:33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malboosbaf F, Azizi F. What is systematic review and how we should write it? Pejouhesh. 2010;34:203–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biniaz V. A review of the world-wide researches on the therapeutic effects of ginger during the past two years. Jentashapir J Health Res. 2013;4:333–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khayat S, Kheirkhah M, Behboodi Moghadam Z, Fanaei H, Kasaeian A, Javadimehr M, et al. Effect of treatment with ginger on the severity of premenstrual syndrome symptoms. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:792708. doi: 10.1155/2014/792708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandal P, Das A, Majumdar S, Bhattacharyya T, Mitra T, Kundu R, et al. The efficacy of ginger added to ondansetron for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting in ambulatory surgery. Pharmacognosy Res. 2014;6:52–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.122918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montazeri AS, Hamidzadeh A, Raei M, Mohammadiun M, Montazeri AS, Mirshahi R, et al. Evaluation of oral ginger efficacy against postoperative nausea and vomiting: A randomized, double-blinded clinical trial. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15:e12268. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panahi Y, Saadat A, Sahebkar A, Hashemian F, Taghikhani M, Abolhasani E, et al. Effect of ginger on acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A pilot, randomized, open-label clinical trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:204–11. doi: 10.1177/1534735411433201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomson M, Corbin R, Leung L. Effects of ginger for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy: A meta-analysis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27:115–22. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.01.130167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamahara J, Rong H, Iwamoto M, Kobayashi G, Matsuda H, Fujimura H. Active components of ginger exhibiting anti-serotonergic action. Phytother Res. 1989;3:70–1. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marx W, Kiss N, Isenring L. Is ginger beneficial for nausea and vomiting? An update of the literature. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:189–95. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haji Seid Javadi E, Salehi F, Mashrabi O. Comparing the effectiveness of vitamin b6 and ginger in treatment of pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2013;2013:927834. doi: 10.1155/2013/927834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saberi F, Sadat Z, Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi M, Taebi M. Effect of ginger on relieving nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2014;3:e11841. doi: 10.17795/nmsjournal11841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Firouzbakht M, Nikpour M, Jamali B, Omidvar S. Comparison of ginger with Vitamin B6 in relieving nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Ayu. 2014;35:289–93. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.153746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saberi F, Sadat Z, Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi M, Taebi M. Acupressure and ginger to relieve nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: A randomized study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15:854–61. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.12984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ozgoli G, Goli M, Simbar M. Effects of ginger capsules on pregnancy, nausea, and vomiting. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:243–6. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basirat Z, Moghadamnia A, Kashifard M, Sharifi-Razavi A. The effect of ginger biscuit on nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Acta Med Iran. 2009;1:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hosseinkhani N, Sadeghi T. The effect of ginger on pregnancy-induced nausea during first trimester. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 07];Iran J Nurs. 2009 22:75–83. Available from: http://ijn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-716-en.html . [Google Scholar]

- 42.Narenji F, Delavar M, Rafiee M. Comparison of ginger with Vitamin B6 in relieving nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. IJOGI. 2012;15:39–43. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.153746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narenji F, Delarvar M, Rafie M. Comparison of ginger powder and fresh root of ginger on the nausea and vomiting of the pregnancy. J Complement Med Res. 2013;2013:336–43. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Modares M, Besharat S, Mahmoudi M. Effect of ginger and chamomile capsules on nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2012;14:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alankar S. A review on peppermint oil. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 07];Asian J Pharma Clin Res. 2009 2:27–33. Available from: https://innovareacademics.in/journal/ajpcr/Vol2Issue2/187.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stea S, Beraudi A, De Pasquale D. Essential oils for complementary treatment of surgical patients: State of the art. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2014/726341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmed EM, Soliman SM, Mahmoud HM. Effect of peppermint as one of carminatives on relieving gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) during pregnancy. J Am Sci. 2012;8:132–143. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pasha H, Behmanesh F, Mohsenzadeh F, Hajahmadi M, Moghadamnia AA. Study of the effect of mint oil on nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14:727–30. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joulaee Rad N. Effect of Inhaling the Fragrance of Peppermint on Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy in Women Referred to Selected Health Centers of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tayarani-Najaran Z, Talasaz-Firoozi E, Nasiri R, Jalali N, Hassanzadeh M. Antiemetic activity of volatile oil from Mentha spicata and Mentha piperita in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Ecancermedicalscience. 2013;7:290. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2013.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.González-Molina E, Domínguez-Perles R, Moreno D, García-Viguera C. Natural bioactive compounds of Citrus limon for food and health. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2010;51:327–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arias BA, Ramón-Laca L. Pharmacological properties of citrus and their ancient and medieval uses in the Mediterranean region. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yavari kia P, Safajou F, Shahnazi M, Nazemiyeh H. The effect of lemon inhalation aromatherapy on nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: A double-blinded, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e14360. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.14360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharma R. Cardamom comfort. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2012;9:237. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.95243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ullah Khan A, Khan Q, Gilani A. Pharmacological basis for the medicinal use of cardamom in asthma. Bangladesh J Pharmacol. 2011;6:34–7. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sailesh K. A study on anti hyper lipidemic effect of oral administration of cardamom in Wistar albino rats. Narayana Med J. 2013;2:31–9. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agaoglu S, Dostbil N, Alemdar S. Antimicrobial effect of seed extract of Cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum Maton) Vet. Fak. Derg. 2005;16:99–101. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khalili Z, Khatiban M, Faradmal J, Abbasi M, Zeraati F, Khazaei A. Effect of cardamom aromas on the chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in cancer patients. Sci J Hamadan Nurs Midwifery Faculty. 2014;22:64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ozgoli G, Gharayagh Zandi M, Nazem Ekbatani N, Allavi H, Moattar F. Cardamom powder effect on nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Complement Med J. 2015;14:1056–76. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harmon D, Gardiner J, Harrison R, Kelly A. Acupressure and the prevention of nausea and vomiting after laparoscopy. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:387–90. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steele NM, French J, Gatherer-Boyles J, Newman S, Leclaire S. Effect of acupressure by Sea-Bands on nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2001;30:61–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dundee JW, McMillan C. Positive evidence for P6 acupuncture antiemesis. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67:417–22. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.67.787.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rowbotham DJ. Recent advances in the non-pharmacological management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:77–81. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ouyang H, Chen J. Therapeutic roles of acupuncture in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharm Ther. 2004;20:831–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ozgoli G, Shahbazzadegan S, Rasaeian Z, Alavi Majd H. The effect of acupressure wristbands on pregnancy nausea and vomiting. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci. 2008;7:247–53. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Forouhari S, Ghaemi SZ, Roshandel A, Moshfegh Z, Rostambeigy P, Mohaghegh Z. The effect of acupressure on nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Researcher. 2014;6:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saberi F, Sadat Z, Abedzadeh-Kalahroodi M, Taebi M. Impact of acupressure on nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Feyz J Kashan Univ Med Sci. 2012;16:212–8. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nurani S, Aparnak F, Sar-Nabavi R, Ebrahimzadeh S. Comparison of acupressure on P6 with K1-K9 in relieving nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. J Urmia Med Sci. 2011;22:369–78. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aga-Miri Z, Hosseini N, Ramazanzadeh F, Hagollahi F, Vijeh M. Effect of acupressure on the frequency and severity of nausea in pregnancy. J Payesh. 2008;7:370–4. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tadion M, Salehian T, Abaspour Z, Latifi M. Comparison of acupressure with Vitamin B6 in relieving nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. J Med Sci. 2000;4:196–200. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Soltanzadeh M, Behaeen K, Pourmehdi Z, Safarimohsenabadi A. Effects of acupressure on nausea and vomiting after gynecological laparoscopy surgery for infertility investigations. Life Sci J. 2012;9:871–5. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Augustine A, Devi E, Latha T. Effectiveness of acupressure on chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting and the functional status among cancer patients receiving cisplatin as radiosensitizer chemotherapy in Kasturba hospital Manipal. Int J Nurs Educ. 2015;7:32. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Naeimi Rad M, Lamyian M, Heshmat R, Jaafarabadi MA, Yazdani S. A randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of KID21 point (Youmen) acupressure on nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14:697–701. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Waite RC, Velleman Y, Woods G, Chitty A, Freeman MC. Integration of water, sanitation and hygiene for the control of neglected tropical diseases: A review of progress and the way forward. Int Health. 2016;8(Suppl 1):i22–7. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihw003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moradi Lakeh M, Taleb AM, Saeidi M. Efficacy and safety of ginger to reduce nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Payesh. 2008;7:345–54. [Google Scholar]

- 76.White B. Ginger: An overview. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:1689–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sontakke S, Thawani V, Naik M. Ginger as an antiemetic in nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy: A randomized, cross-over, double blind study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2003;35:32–6. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bryer E. A literature review of the effectiveness of ginger in alleviating mild-to-moderate nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50:e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pongrojpaw D, Somprasit C, Chanthasenanont A. A randomized comparison of ginger and dimenhydrinate in the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90:1703–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shawahna R, Taha A. Which potential harms and benefits of using ginger in the management of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy should be addressed? a consensual study among pregnant women and gynecologists. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17:204. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1717-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Clement-Jones V, McLoughlin L, Tomlin S, Besser GM, Rees LH, Wen HL, et al. Increased beta-endorphin but not met-enkephalin levels in human cerebrospinal fluid after acupuncture for recurrent pain. Lancet. 1980;2:946–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Samad K, Afshan G, Kamal R. Effect of acupressure on postoperative nausea and vomiting in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Pak Med Assoc. 2003;53:68–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shin H, Song Y, Seo S. Effect of Nei-Guan point (P6) acupressure on ketonuria levels, nausea and vomiting in women with hyperemesis gravidarum. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59:510–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin X, Liang J, Ren J, Mu F, Zhang M, Chen JD, et al. Electrical stimulation of acupuncture points enhances gastric myoelectrical activity in humans. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1527–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Van den Heuvel E, Goossens M, Vanderhaegen H, Sun HX, Buntinx F. Effect of acustimulation on nausea and vomiting and on hyperemesis in pregnancy: A systematic review of western and Chinese literature. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:13. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-0985-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Matthews A, Dowswell T, Haas D, Doyle M, Dónal P, ‘Mathúna O. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9:1–68. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007575.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lete I, Allué J. The effectiveness of ginger in the prevention of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy and chemotherapy. Integr Med Insights. 2016;11:11. doi: 10.4137/IMI.S36273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]