Abstract

Sorafenib is used worldwide as a first-line standard systemic agent for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) on the basis of the results of two large-scale Phase III trials. Conversely, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) is one of the most recommended treatments in Japan. Although there have been no randomized controlled trials comparing sorafenib with HAIC, several retrospective analyses have shown no significant differences in survival between the two therapies. Outcomes are favorable for HCC patients exhibiting macroscopic vascular invasion when treated with HAIC rather than sorafenib, whereas in HCC patients exhibiting extrahepatic spread or resistance to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, good outcomes are achieved by treatment with sorafenib rather than HAIC. Additionally, sorafenib is generally used to treat patients with Child-Pugh A, while HAIC is indicated for those with either Child-Pugh A or B. Based on these findings, we reviewed treatment strategies for advanced HCC. We propose that sorafenib might be used as a first-line treatment for advanced HCC patients without macroscopic vascular invasion or Child-Pugh A, while HAIC is recommended for those with macroscopic vascular invasion or Child-Pugh A or B. Additional research is required to determine the best second-line treatment for HAIC non-responders with Child-Pugh B through future clinical trials.

Keywords: Treatment strategy, Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, Sorafenib, Hepatocellular carcinoma

Core tip: In Japan, sorafenib and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) are described as treatment options for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Although no randomized controlled trials have compared these treatments, retrospective analyses have shown similar survival between them. Sorafenib is generally used for Child-Pugh A, while HAIC is indicated for Child-Pugh A or B. Compared to sorafenib, HAIC shows better responses in cases exhibiting macroscopic vascular invasion. After reviewing treatment strategies for advanced HCC, we recommended sorafenib as first-line treatment for cases without macroscopic vascular invasion or Child-Pugh A, and HAIC for those with macroscopic vascular invasion or Child-Pugh A or B.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second most common cause of cancer related death worldwide[1]. According to the Global Burden of Disease 2015 study of 195 countries, the number of liver cancer cases increased by 75% between 1990 and 2015, and hepatitis B virus (HBV) was responsible for 33% of global liver cancer mortality compared to 30% from alcohol, 21% from hepatitis C virus (HCV), and 15% from other causes[2]. However, the incidence of both HBs antigen-negative and HCV antibody-negative HCC (non-B, non-C HCC) has recently increased in Japan[3,4]. As there are not yet any established surveillance programs for non-B, non-C HCC patients, it is difficult to diagnose such patients at an earlier disease stage. Therefore, the number of advanced HCC patients at the time of diagnosis may be increasing in Japan. Additionally, even if an earlier disease stage of HCC is detected, many patients progress to an advanced stage because of frequent recurrence of the disease. Therefore, it is now more important than ever to develop a treatment for advanced HCC. In this review, we review the treatment strategies for advanced HCC, particularly sorafenib and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC).

GUIDELINES FOR ADVANCED HCC

The results of the global investigation of therapeutic decisions in HCC and of its treatment with sorafenib (GIDEON) study show differences in the management of HCC, including diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring, among several regions. In consequence, there have been regional differences in patient outcomes[5]. Although several guidelines for the clinical management of HCC have been established worldwide, there are some differences in the treatment algorithms among these guidelines. Table 1 shows the major recent guidelines from Asia, Europe and the United States[6-13]. The Barcelona clinic liver cancer (BCLC) staging system, which stratifies patients by tumor stage and underlying liver disease, is widely accepted in clinical practice[14]. Among the five HCC stages (BCLC 0, A, B, C and D), the advanced BCLC C stage includes symptomatic patients with performance status (PS) 1-2, vascular invasion, extrahepatic spread, or a combination thereof[14]. For patients with BCLC C and good liver function (Child-Pugh A), sorafenib is the preferred first-line treatment according to guidelines from Europe and the United States[11-13]. According to guidelines from Asia[7-9], systemic therapy (molecular-targeted drugs) or transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is recommended as standard treatment for such patients. However, HAIC is not generally recommended as a standard of care in the above-mentioned guidelines.

Table 1.

Guidelines for the clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma

| Publishing year | Guidelines | Drafted by | Treatment algorithm for advanced HCC (BCLC C) | Ref. | |

| Asia | 2014 | JSH-LCSGJ | Japan Society of Hepatology and Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan | HAIC (Vp1-4), Sorafenib (Vp1-3), TACE (Vp1, 2), Resection (Vp1, 2) | [6] |

| 2014 | KLCSG-NCC | Korean Liver Cancer Study Group and National Cancer Center | TACE, Sorafenib | [7] | |

| 2014 | HKLC | Hong Kong Liver Cancer | Systemic therapy, Supportive care | [8] | |

| 2017 | APASL | Asian-Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver | Systemic therapy (sorafenib and regorafenib), TACE for patients with no extrahepatic metastasis | [9] | |

| 2017 | JSH | Japan Society of Hepatology | TACE, Resection, HAIC, Molecular targeted agents | [10] | |

| Europe | 2018 | EASL | European Association for the Study of the Liver | Sorafenib (sorafenib, lenvatinib, regorafenib, and cabozantinib) | [11] |

| 2012 | ESMO-ESDO | European Society for Medical Oncology and European Society of Digestive Oncology | Sorafenib | [12] | |

| United States | 2011 | AASLD | American Association for the Study of Liver Disease | Sorafenib | [13] |

HAIC: Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; Vp1-4: Portal vein invasion according to JSH-LCSGJ; TACE: Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization; BCLC: Barcelona clinic liver cancer.

Whereas sorafenib and HAIC are indicated for the patients with minor portal vein invasion (so-called Vp1, 2) or portal invasion at the first portal branch (so-called Vp3) in the Japan Society of Hepatology and Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan (JSH-LCSGJ) Consensus-based Treatment Algorithm for HCC revised in 2014, HAIC, but not sorafenib, is recommended for portal invasion at the main trunk of the portal vein (so-called Vp4)[6]. Furthermore, according to the most recent version (2017) of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for HCC proposed by JSH, TACE, resection, HAIC, and molecular-targeted agents are equally recommended for HCC patients with portal invasion. It has also been argued that the treatment should be selected after considering all of the patient’s conditions as a whole[10].

Finally, the 2017 version of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines supports HAIC for unresectable HCC; however, its use in the context of a clinical trial is preferred[15].

SORAFENIB FOR ADVANCED HCC

Current status of sorafenib

Sorafenib is an oral multi-targeted kinase inhibitor that suppresses tumor growth, and it was the first drug to demonstrate a survival benefit in patients with advanced HCC. In two large-scale Phase III trials, although the response rate of sorafenib was only 2%-3.3% according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), sorafenib treatment significantly improved overall survival (OS) [sorafenib vs placebo median survival time (MST): 10.7 mo vs 7.9 mo, hazard ratio (HR): 0.69, P < 0.001 in the SHARP trial; and MST: 6.5 mo vs 4.2 mo, HR: 0.68, P = 0.014 in the Asia-Pacific trial] and the time-to-progression (TTP) (sorafenib vs placebo median TTP: 5.5 mo vs 2.8 mo, HR: 0.58, P < 0.001 in the SHARP trial; and TTP: 2.8 mo vs 1.4 mo, HR: 0.57, P = 0.0005 in the Asia-Pacific trial) in patients with advanced HCC[16,17]. Therefore, sorafenib is utilized as a standard first line agent for the treatment of advanced HCC worldwide[6-13]. Recently, Rimola et al[18] reported that 1% of patients treated with sorafenib (12/1119) exhibited complete response (CR), according to RECIST, and the MST for those patients was 85.8 mo.

For several years, antiangiogenic tyrosine-kinase inhibitors other than sorafenib have failed in Phase III clinical trials[19,20]. However, recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of two oral multi-kinase inhibitors, the second-line agent regorafenib, which is used for sorafenib-resistant HCC, and the first-line agent lenvatinib, which has been shown to be non-inferior to sorafenib for OS[21,22].

Regorafenib has been reported as a second-line agent following sorafenib because of improvement in OS (regorafenib vs placebo MST: 10.6 mo vs 7.8 mo, HR: 0.63, P < 0.0001) (RESORCE trial)[21]. According to the results of this study, regorafenib was approved in the United States and Japan in 2017.

Lenvatinib is an oral multi-target inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors 1-3, fibroblast growth factor receptors 1-4, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, KIT, and RET[23]. A comparative global Phase III trial of lenvatinib in the first-line setting (REFLECT trial) demonstrated non-inferiority to sorafenib in advanced HCC patients (lenvatinib vs sorafenib MST: 13.6 mo vs 12.3 mo, HR: 0.92)[22]. In addition, the progression-free survival (PFS), TTP, and overall response rate (ORR) were significantly better in patients treated with lenvatinib than in those treated with sorafenib (lenvatinib vs sorafenib, median PFS: 7.4 mo vs 3.7 mo, HR: 0.66, P < 0.0001; median TTP: 8.9 mo vs 3.7 mo, HR 0.63, P < 0.0001; ORR: 24.1% vs 9.2%, P < 0.0001). Lenvatinib is approved for unresectable thyroid cancer and has been usable for HCC in Japan prior to it being approved in the rest of the world. However, HCC patients with 50% or higher liver occupation, bile duct invasion, or main portal invasion met the exclusion criteria of the REFLECT trial. Such HCC patients may be candidates for general usage of sorafenib.

Predictive factors for response and survival

Bruix et al[24] conducted analyses of two large trials (827 patients, SHARP and Asia-Pacific trials) and reported prognostic factors. According to this report, vascular invasion, high alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and high neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) were prognostic factors for poorer OS, while lack of extrahepatic spread, HCV, and low NLR were predictive factors for greater sorafenib benefit[24]. Among serum and plasma factors, VEGF[25-27], angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2)[25,26], AFP[25,26,28-31], NLR[32,33], TIE-2 expressing monocytes (TEMs)[34], microRNA[35-37], and circulating tumor cells (CTCs)[38] have been identified as potential biomarkers (Table 2). The expression of phospho-ERK[39-41], phospho-c-Jun[42], and VEGFR-2[41], and amplification of FGF3/FGF4[43], have been identified as possible predictive biomarkers in tissues (Table 3). In studies of imaging biomarkers, it has been reported that decreased blood flow after sorafenib treatment[44] and low pretreatment standardized uptake values of 13F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in positron emission tomography (PET)[45] are associated with prolonged OS. Although there have been several reports of a correlation between adverse effects (hypertension, skin toxicity, diarrhea, etc.) and sorafenib efficacy, it has been difficult to establish conclusions because of difference in the frequencies of these adverse effects among patients of different races. However, Howell et al[46] reported that patients with sorafenib-related toxicity such as diarrhea, hypertension, and hand-foot syndrome, had good prognoses in a large, multicenter prospective cohort study. Furthermore, the potential of other biomarkers has been explored[47]. Although several studies have investigated predictive biomarkers for response and survival associated with sorafenib, no such biomarkers have been established.

Table 2.

Serum and plasma biomarkers of sorafenib response and survival

| Biomarkers | Ref. | Publishing year | Case number | Predictive factors for response | Predictive factors for survival | Others |

| VEGF | Llovet et al[25] | 2012 | 299 | No predictive value | Not prognostic value | |

| Miyahara et al[26] | 2013 | 120 | No predictive value | Not prognostic value | ||

| Tsuchya et al[27] | 2014 | 63 | No predictive value | VEGF response (a > 5% decrease during 8 wk of treatment): Better OS | ||

| Ang-2 | Llovet et al[25] | 2012 | 299 | No predictive value | Low Ang-2: Better OS | |

| Miyahara et al[26] | 2013 | 120 | High Ang2: PD | Low Ang-2: Better OS | ||

| Changes of AFP | Personeni et al[28] | 2012 | 85 | AFP response (a > 20% decrease during 8 wk of treatment): Better ORR, DCR | AFP response: Better OS | |

| Yau et al[29] | 2011 | 94 | AFP response (a > 20% decrease during 6 wk of treatment): Better DCR | AFP response: Better PFS | ||

| Kuzuya et al[30] | 2015 | 47 | - | High AFP ratio (a > 1.2 at 2 wk relative to baseline): Poor OS | High poor prognostic score (the absence of disapperance of arterial tumor enhancement on CE-CT, AFP ratio of > 1.2, and two or more increments in CP score after 2 wk of Treatment): Poor OS and DCR | |

| Nakazawa et al[31] | 2013 | 59 | AFP increase (more than 20% from baseline during 4 wk of treatment): PD | AFP increase: Better OS and PFS | ||

| AFP | Llovet et al[25] | 2012 | 299 | - | AFP > 200 ng/mL: Poor OS | |

| Miyahara et al[26] | 2013 | 120 | - | Not prognostic value | ||

| Kuzuya et al[30] | 2015 | 47 | - | Not prognostic value | ||

| NLR | Zheng et al[32] | 2013 | 65 | - | High NLR (> 4): Poor OS and TTP | |

| Howell et al[33] | 2017 | 175 | - | High NLR (> 2.52): Poor OS | ||

| TEMs | Shoji et al[34] | 2017 | 25 | High ΔTEMs (changes in TEMs before and at 1 mo after therapy): PD | High ΔTEMs (changes in TEMs before and at 1 mo after therapy): Poor OS | |

| MicroRNA | Stiuso et al[35] | 2015 | 39 | Upregulation of miR-423-5p after treatment: SD or PR | - | |

| Yoon et al[36] | 2017 | 24 | - | Low miR-10b-3p: Poor OS | ||

| Nishida et al[37] | 2017 | 53 | High miR-181a-5p: PR + SD | High miR-181a-5p: Better OS | ||

| CTCs | Li et al[38] | 2016 | 59 | pERK+/pAkt- CTCs: Better DCR | pERK+/pAkt- CTCs: Better DCR |

Ang-2: Angiopoietin-2; CE-CT: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography; NLR: Neutrophil-to lymphocyte ratio; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; CTC: Circulating tumor cells; TEMs: TIE-2-expression monocytes; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; PD: Progressive disease; OS: Overall survival; DCR: Disease control rate; ORR: Overall response rate; PFS: Progression-free survival; CP: Child-Pugh; pERK: Phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase; PR: Partial response; SD: Stable disease; TTP: Time to progression.

Table 3.

Tissue biomarkers of sorafenib response and survival

| Biomarkers | Ref. | Publishing year | Case number | Predictive factors for response | Predictive factors for survival |

| Expression of p-ERK | Abou-Alfa et al[39] | 2012 | 33 | - | High pERK: Longer TTP |

| Chen et al[40] | 2013 | 54 | - | High pERK: Longer TTP | |

| Negri et al[41] | 2015 | 77 | - | High pERK: Shorter OS and PFS | |

| Expression of p-c-Jun | Hagiwara et al[42] | 2012 | 39 | High p-c-jun: Poor response | High p-c-jun: Shorter TTP and OS |

| Expression of VEGFR-2 | Negri et al[41] | 2015 | 54 | - | High VEGFR-2: Shorter OS and PFS |

| FGF3/FGF4 amplification | Arao et al[43] | 2013 | 48 | FGF3/FGF4 amplification: Responder | - |

ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FGF: Fibroblast growth factor; TTP: Time to progression; OS: Overall survival; pERK: Phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase; PFS: Progressive-free survival; VEGFR: Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

HAIC FOR ADVANCED HCC

Current status of HAIC

In HAIC, as it is theoretically possible to accumulate local concentrations of anti-cancer drugs in the liver and to reduce their systemic distribution, it is believed to have a stronger antitumor effect and lower incidence of adverse reactions compared with systemic chemotherapy. On the other hand, one disadvantage is the need to master the HAIC procedure, and several adverse effects are associated with HAIC including inflammation of blood vessels, arterial obstructions, peptic ulcers due to drug leakage, and infections or obstructions of reservoir catheters.

According to the 2017 version of the treatment algorithm for HCC produced by JSH[10], HAIC is recommended as a second-line treatment for patients with ≥ 4 HCCs and an absence of portal invasion, while HAIC is considered a first-line treatment for those with portal invasion.

HAIC has become widely used in Asia, especially Japan, where the main HAIC regimens are low-dose cisplatin (CDDP) combined with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (low-dose FP)[48-51], interferon (IFN) in combination with 5-FU (FAIT)[50,52,53], and CDDP alone[51,54-56] (Table 4). In both low-dose FP and FAIT regimens, the key drug is 5-FU. In addition, CDDP or IFN exert their own effects to amplify the effect of 5-FU, and they are therefore considered biochemical modulators of 5-FU. Moreover, one benefit of the CDDP alone regimen is that a catheter is inserted each time, making the troublesome implantation of a reservoir catheter unnecessary. The regimens using low-dose FP or FAIT have response rates of approximately 30%-40%, while the CDDP alone regimen has rates of approximately 20%-30% (Table 4)[48-53,55-57]. Survival is significantly better in patients with radiological response [CR or partial response (PR)] (so-called responders) than in patients with radiological no-response (stable or progressive disease) (so-called non-responders).

Table 4.

Regimens of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

| Ref. | Publishing year | Case number | Vascular invasion (%) | Regimens | Response rate (%) | Median survival time (mo) |

| Saeki et al[48] | 2015 | 90 | ND | Low-dose FP, including the combination of LV/IV or IV plus IFN | 34.4 | 10.6 |

| Nouso et al[49] | 2013 | 476 | 44.1 | CDDP + 5-FU | 40.5 | 14.0 (341 patients) |

| Monden et al[50] | 2012 | 34 | 90 | IFNα, 5-FU | 26.7 | 8.4 |

| 35 | 90.3 | Low-dose FP/CDDP | 25.8 | 11.8 | ||

| Yamashita et al[52] | 2011 | 57 | 26.7 | IFNα, CDDP, 5-FU | 45.6 | 17.6 |

| 57 | 50 | IFNα, 5-FU | 24.6 | 10.5 | ||

| Nagano et al[57] | 2011 | 102 | 100 | IFNα, 5-FU | 39.2 | 9 |

| Obi et al[53] | 2006 | 116 | 100 | IFNα, 5-FU | 52 | 6.9 |

| Ikeda et al[54] | 2013 | 25 | 100 | CDDP powder (IA call) | 28 | 7.6 |

| Iwasa et al[55] | 2011 | 84 | 31 | CDDP powder (IA call) | 3.6 | 7.1 |

| Kim et al[51] | 2011 | 41 | 83.3 | CDDP | 12.2 | 7.5 |

| 97 | CDDP, 5-FU | 27.8 | 12 | |||

| Yoshikawa et al[56] | 2008 | 80 | 27.5 | CDDP powder (IA call) | 33.8 | ND |

ND: Not described; Low-dose FP: Low-dose 5-FU plus Cisplatin; LV: Leucovorin; IV: Isovorin; IFN: Interferon; CDDP: Cisplatin.

The principal reasons for low clinical recognition of HAIC are the small sample size of almost all studies and the lack of large randomized trials. However, effective results have been demonstrated by previous studies. In a report comparing the FAIT regimen of HAIC with historical controls, HAIC was shown to significantly improve survival[53]. A Japanese nationwide survey supported the efficacy of the low-dose FP regimen of HAIC for treating advanced HCC[49]. After adjusting for known risk factors, survival benefits of this therapy were evident (HR: 0.48, 95%CI: 0.41-0.56, P < 0.0001). In a propensity score-matched analysis, the MST was longer in patients who received HAIC (n = 341, 14.0 mo) than in those who did not receive active treatment (n = 341, 5.2 mo) (HR: 0.60, 95%CI: 0.49-0.73, P < 0.0001). In cases of Child-Pugh A or B disease with more than three tumors (370 propensity score-matched patients), the MST was longer in patients treated with HAIC (13.9 mo) than in those with no therapy (3.7 mo) (P < 0.0001). In cases of Child-Pugh A or B disease with portal vein tumor thrombus (378 propensity score-matched patients), the MST was also longer in patients treated with HAIC (7.9 mo) than in those with no therapy (3.1 mo) (P < 0.0001).

Predictive factors for response and survival

As HAIC is selected for advanced HCC patients with poor prognoses, it is important to identify predictive factors for response and survival (Table 5)[48,49,53,58-61].

Table 5.

Predictive factors for response and survival of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

| Ref. | Publishing year | Case number | Regimens | Poor predictive factors for response | Poor predictive factors for survival |

| Saeki et al[48] | 2015 | 90 | Low-dose FP with/without LV, IV, or IV plus IFN | DCP reduction or increase of < 20% from baseline to 2 wk after HAIC | Child-Pugh B, AFP reduction or increase of < 20% from baseline to 2 wk after HAIC, DCP reduction or increase < 20% from baseline to 2 wk after HAIC |

| Terashima et al[58] | 2015 | 266 | IFNα, 5-FU with/without CDDP | NLR ≥ 2.87 (cut-off, median value), presence of vascular invasion, presence of extrahepatic metastasis | NLR ≥ 2.87 (cut-off, median value), ECOG PS 1/2, Child-Pugh score 8-9, presence of extrahepatic metastasis, CRP ≥ 0.8 mg/dL, AFP ≥ 235.5 ng/mL |

| Zaitsu et al[59] | 2014 | 44 | Low-dose FP with/without IV, or IV plus IFN | ND | Child-Pugh B, serum transferrin < 190 mg/dL |

| Nouso et al[49] | 2013 | 476 | CDDP + 5-FU | ND | HBs antigen positive, Child-Pugh B, tumor number > 3, tumor size > 3 cm, presence of extrahepatic metastasis, Vp3/4, AFP > 400 ng/mL |

| Niizeki et al[60] | 2012 | 71 | Low-dose FP | VEGF ≥ 100 pg/mL | Child-Pugh B, VEGF ≥ 100 pg/mL, therapeutic effect SD + PD |

| Miyaki et al[61] | 2012 | 249 | Low-dose FP (106 patients); IFNα, 5-FU (143 patients) | HCV antibody negative, platelet count ≥ 15 × 104/μL | ECOG PS 1-2, Child-Pugh score 8-9, presence of extrahepatic metastasis, AFP ≥ 1000 ng/mL, abcence of additional therapy, theraputic effect SD + PD + DO |

| Obi et al[53] | 2006 | 116 | IFNα, 5-FU | Not detect | Vp4, Total bilirubin ≥ 1.0 mg/dL, theraputic effect PR + SD + PD |

Low-dose FP: Low-dose 5-FU plus Cisplatin; LV: Leucovorin; IV: Isovorin; IFN: Interferon; CDDP: Cisplatin; DCP: Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin; NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; ND: Not described; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; PS: Performance status; SD: Stable disease; PD: Progressive disease; DO: Drop-out; CR: Complete response.

The predictive factors for poor response to HAIC include the presence of vascular invasion[58], the presence of extrahepatic metastasis[58], NLR ≥ 2.87[58], a concentration of serum VEGF ≥ 100 pg/mL[60], a negative HCV antibody test result[61], and a platelet count ≥ 15 × 104/μL[61], and a negative des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin (DCP) response [defined as a reduction of < 20% or an increase from baseline after a half course of HAIC (2 wk)][48].

Survival benefits for HAIC have been reported in HAIC responders[53,60,61]. However, therapeutic effect is not an effective prognostic predictor. The poor prognostic predictors include not only tumor-associated factors, such as more than three tumors[49], large tumors (> 3 cm)[49], the presence of vascular invasion[49,53], the presence of extrahepatic metastasis[49,58,61] and high AFP levels[49,58,61], but also those associated with the patient, including dysfunction of the liver reserve[48,49,53,58-61], ECOG PS 1-2[58,61], and a positive HBs antigen test result[49]. Additionally, poor prognostic predictors include negative responses of AFP or DCP[48], high levels of inflammation-related markers such as NLR and CRP[58], low transferrin levels (< 190 mg/dL)[59] and high VEGF levels (≥ 100 pg/mL)[60].

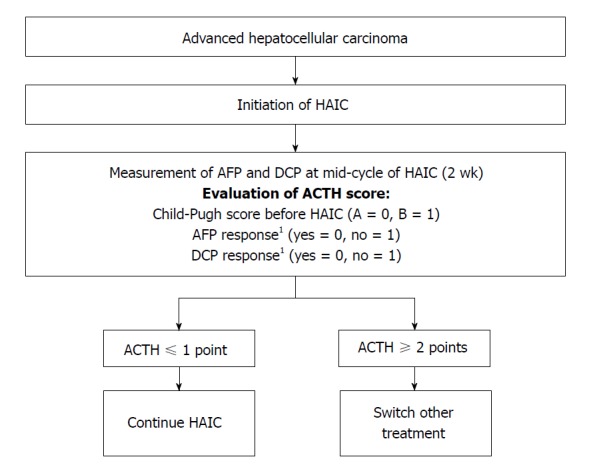

A new assessment score: Assessment for continuous treatment with HAIC

It is important to identify the effective benefit of early HAIC treatment in HCC patients. Therefore, we developed a new therapeutic assessment score to guide decisions regarding HAIC treatment, the Assessment for Continuous Treatment with HAIC (ACTH)[48]. The ACTH score (range, 0-3) is calculated from simple three parameters: Child-Pugh score before HAIC (A = 0, B = 1), AFP response (yes = 0, no = 1), and DCP response (yes = 0, no = 1). The tumor markers’ responses are assessed as the difference between the baseline and 2 wk after HAIC induction (positive response: A reduction of ≥ 20% from the baseline). ACTH score could stratify patients’ survival (score ≤ 1 vs score ≥ 2, 15.1 mo vs 8.7 mo; P = 0.003)[48]. A validation study similarity showed that this score is useful for therapeutic assessment[62]. Therefore, the ACTH score makes it possible to provide an early prediction of the prognosis of advanced HCC patients receiving HAIC, and can improve treatment efficiency by switching to other treatments, such as sorafenib or an experimental treatment in a clinical trial, for patients with a score ≥ 2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Treatment strategy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma according to the hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy score to assess continuous treatment. The score (range, 0-3) was calculated as follows: Child-Pugh score before hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) (A = 0, B = 1), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) response (yes = 0, no = 1), and des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin (DCP) response (yes = 0, no = 1). For patients with a score ≤ 1, HAIC treatment would be continued, while for patients with a score ≥ 2, a second-line therapy such as sorafenib and/or participation in a new clinical trial would be a better option. 1The AFP and DCP responses were assessed 2 wk after HAIC induction; a positive response is defined as a reduction of ≥ 20% from baseline. ACTH: Arterial infusion chemotherapy.

Modified HAIC and the combination approach

Nagamatsu et al[63] developed a modified procedure for administering a low-dose FP regimen: HAIC using 5-FU after lipiodol-transcatheter arterial infusion chemotherapy (Lip-TAI) with CDDP; a multicenter phase II study showed that the MST and response rate were 27.0 mo and 75% for advanced HCC patients with portal vein thrombosis, respectively[64]. Although this regimen produced a favorable outcome, it has not become widespread owing to the high level of proficiency needed for the procedure.

A multicenter open-labeled randomized Phase II trial was conducted to evaluate the effect of combining the CDDP regimen of HAIC with sorafenib for treating advanced HCC. The results showed that survival was significantly better for patients receiving sorafenib plus HAIC (MST, 10.6 mo) than those receiving sorafenib alone (MST, 8.7 mo) (HR: 0.60, P = 0.031)[65]; however, there was not a significant difference in survival between patients receiving sorafenib plus HAIC using low-dose FP and those receiving sorafenib alone[66]. Therefore, further investigation is required.

Radiotherapy (RT) has become recognized as an optional treatment for HCC in the APASL and NCCN guidelines[9,15], but it is not recommended in the AASLD and EASL guidelines[11,13]. For advanced HCC patients with intravascular tumor thrombus, a combination of HAIC with RT is a reasonable approach. Compared to HAIC alone, a beneficial effect of 3-D conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) for major portal vein tumor thrombosis combined with HAIC has been demonstrated, although these results came from retrospective cohort studies[67,68].

SORAFENIB VS HAIC

Sorafenib is recommended as a first-line treatment worldwide for advanced HCC patients (those with BCLC-C HCC)[11-13]. Because of the low response rate to sorafenib, we suggest that maintaining the stability of HCC by suppressing tumor growth can significantly improve survival. Sorafenib therapy also worsens survival in patients with Child-Pugh B, unlike those with Child-Pugh A[69]. Therefore, advanced HCC patients with Child-Pugh A are candidates for general usage of sorafenib.

On the other hand, HAIC is not widely recommended as a standard of care for advanced HCC patients. As HAIC is thought to be one of the most effective treatment options for such patients, HAIC has become widely used in Asia, especially Japan. We propose that HAIC might be used as a treatment for achieving CR or PR. If patients with PR after HAIC receive additional therapies such as surgical resection, local ablation, or radiation, it is possible for those who show a disappearance of viable HCC to have a long survival time[64]. In addition, although liver reserve dysfunction is a poor prognostic factor[48,49,53,58-61], advanced HCC patients with Child-Pugh B are candidates for HAIC[6,10].

Currently, no criteria have been established for selecting advanced HCC patients to receive either sorafenib or HAIC. According to the results of two largescale randomized controlled trials (RCTs), sorafenib indeed improved the survival of patients with macroscopic vascular invasion[16,17]. However, these HCC patients with macroscopic vascular invasion have poorer prognoses than those without such invasion[16,17,70,71]. Moreover, there have been no RCTs comparing sorafenib with HAIC. In a retrospective cohort study, while there was no significant difference in survival between the sorafenib group and the HAIC group, survival was significantly better in the HAIC group than in the sorafenib group among patients with macroscopic vascular invasion (14 mo vs 7 mo, P = 0.005)[72]. A propensity score matched analysis also showed no significant differences in survival or disease progression between the two groups, while PFS was significantly longer in the HAIC group than in the sorafenib group, particularly for patients with portal vein invasion and/or without extrahepatic spread[73]. On the other hand, survival was favorable in patients with HCC refractory to TACE treated with sorafenib rather than HAIC[74]. Furthermore, it is important to preserve liver function during and after chemotherapy in advanced HCC patients. It has been reported that liver function after therapy was not significantly reduced in patients treated with HAIC compared with those treated with sorafenib[75], and the Child-Pugh score of HAIC responders with deteriorated liver function was significantly improved after HAIC[76]. According to our report[62], most HAIC responders showed no deterioration of liver function. It was interesting to note that the Child-Pugh class of some responders with deteriorated live function improved from B to A after HAIC, but this did not occur in non-responders. Therefore, we conclude that HAIC may be well tolerated by advanced HCC patients with deteriorated liver function.

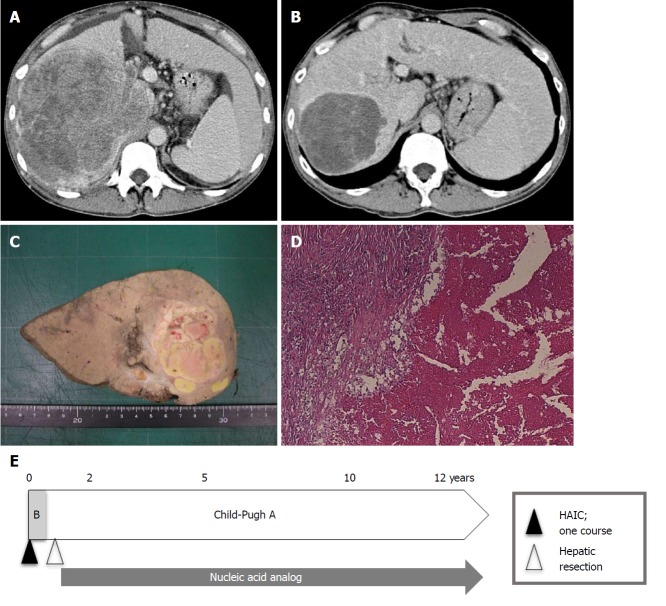

As of 2017, only 10 years have passed since sorafenib was first shown to be efficacious against advanced HCC. As such, it is impossible to assess survival longer than 10 years. However, we can examine survival rates from shorter-duration studies. As previously mentioned, Rimola et al[18] reported a CR rate and MST for CR patients under sorafenib of 1% and 85.8 mo, respectively. Shiba et al[77] reported that the CR rate was below 0.6% (18/3047 patients) in a nationwide study from Japan. By contrast, the CR rate for HAIC was 4.0% (19/476 patients) in a nationwide survey in Japan[49]. According to our previous report[78], the CR rate under HAIC using a low-dose FP-based regimen was 5% (6/114 patients), and overall 1-, 3-, 5-, 7-, and 10-year cumulative survival rates were 43.9%, 10.0%, 5.6%, 2.8%, and 2.8%, respectively (MST, 10.2 mo). Three of six CR patients from our study survived over 10 years, though 2 patients have since died and only one is still alive (Table 6 and Figure 2). Further investigations are required to compare long-term survival rates between sorafenib and HAIC.

Table 6.

Clinical characteristics of three advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients with complete response who have survived over 10 years

| Age diagnosed as HCC | Sex | Etiology | Child-Pugh | Tumor stage1 | Previous treatment | Maximum tumor size (mm) | Vascular invasion1 | Regimen | Therapeutic effect | AFP (ng/mL) | DCP (mAU/mL) | HCC recurrence | Prognosis | Cause of death |

| 67 | Male | HCV | A (5) | IVA | None | 110 | Vp4, Vv0 | Low-dose FP | CR | 120700 | 260 | 62 mo | 151 mo (dead) | Hepatic failure |

| 66 | Male | HCV | A (5) | III | None | 50 | Vp0, Vv0 | Low-dose FP + IV | CR | 6.4 | 2970 | None | 176 mo (dead) | Larynx cancer |

| 44 | Male | HBV | B (7) | III | None | 150 | Vp3, Vv3 | Low-dose FP + IV + Peg IFN | CR | 7145 | 233640 | None | 148 mo (alive2) | - |

According to the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan;

The follow-up period ended on January 31, 2018. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; DCP: Des-γ-carboxyprothrombin; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; CR: Complete remission; Low-dose FP: Low-dose cisplatin combined with 5-FU; IV: Isovorin; Peg IFN: Pegylated interferon.

Figure 2.

Patient with complete response treated with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy using low-dose cisplatin combined with a 5-fluorouracil (low-dose FP)-based regimen. A: This 44-year-old man had massive hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (16 cm in diameter) with tumor thrombosis in the right portal vein (Vp3) and the inferior vena cava (Vv3) on dynamic computed tomography; B: After one course of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC), the liver tumor markedly decreased; however, as slight tumor vascularity remained, the patient was assessed as having partial response at that time; C, D: Three tumor markers [alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), des-γ-carboxyprothrombin (DCP), and AFP L3] decreased after HAIC (AFP from 7145 ng/mL to 12.7 ng/mL, DCP from 233460 mAU/mL to 51 mAU/mL, AFP L3 from 58.1% to 3.1%). The patient’s Child-Pugh classification improved from B (8 points) to A (5 points). Thus, hepatic resection was performed, and histological findings showed no viable tumor cells (C, D). Finally, the patient was considered to have a complete response; E: The patient has been treated with nucleic acid analogs after the operation, and Child-Pugh A has been maintained. The patient is alive without HCC recurrence 148 mo after HAIC treatment.

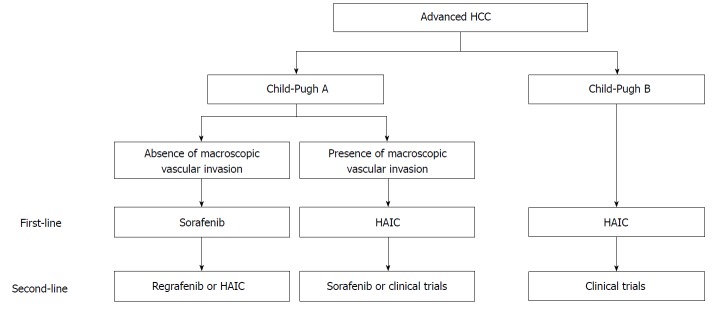

Finally, we present a draft proposal of a treatment strategy for advanced HCC (Figure 3): (1) For advanced HCC patients without macroscopic vascular invasion and Child-Pugh A, the first-line treatment should be sorafenib, and second-line treatments should be either regorafenib[21] or HAIC; (2) For advanced HCC patients with macroscopic vascular invasion and Child-Pugh A, the first-line treatment should be HAIC, and the second-line treatments should be either sorafenib or experimental treatment in clinical trials; (3) For advanced HCC patients with Child-Pugh B, the first-line treatment should be HAIC, and the second-line treatment should be clinical trials. Miyaki et al[79] reported that additional therapy with sorafenib improved the prognosis of HAIC refractory patients compared with that of patients not treated with sorafenib therapy in a retrospective cohort study. Nonetheless, there have been no effective treatments for HAIC non-responders with deteriorated liver function (Child-Pugh B). We have shown the efficacy of an intra-arterial infusion therapy using the iron chelator deferoxamine for advanced HCC patients with deteriorated liver function[78,80], and clinical trials are now ongoing[81]. Because the best second-line treatment for HAIC non-responders with Child-Pugh B is to enroll in clinical trials, this remains an issue for future research.

Figure 3.

Draft proposal of a treatment strategy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. (1) For advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients without macroscopic vascular invasion and Child-Pugh A, the first-line treatment should be sorafenib, while second-line treatments should be either regorafenib or hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC); (2) For advanced HCC patients with macroscopic vascular invasion and Child-Pugh A, the first-line treatment should be HAIC, and the second-line treatments should be either sorafenib or experimental treatment in clinical trials; (3) For advanced HCC patients with Child-Pugh B, the first-line treatment should be HAIC, and the second-line treatment should be clinical trials.

CONCLUSION

We reviewed the current status and predictive biomarkers regarding the administration of sorafenib and HAIC for advanced HCC, and we have proposed a treatment strategy for patients with advanced HCC. The success of sorafenib, regorafenib, and lenvatinib in treating advanced HCC has shifted the treatment paradigm to molecular-targeted therapies. Furthermore, several immune-oncologic agents have been identified with potential for the treatment of advanced HCC[82,83]. Thus, the chemotherapeutic interventions for advanced HCC have been kept up-to-date through several advances. However, alternative therapies will be required because of the high cost and ineffectiveness of these molecular agents for patients with deteriorated liver function.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: March 27, 2018

First decision: April 18, 2018

Article in press: August 7, 2018

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hashimoto N, Roohvand F, Streba CT S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

Contributor Information

Issei Saeki, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan.

Takahiro Yamasaki, Department of Oncology and Laboratory Medicine, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan. t.yama@yamaguchi-u.ac.jp.

Masaki Maeda, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan.

Takuro Hisanaga, Department of Medical Education, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan.

Takuya Iwamoto, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan.

Koichi Fujisawa, Center of Research and Education for Regenerative Medicine, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi, 755-8505, Japan.

Toshihiko Matsumoto, Department of Oncology and Laboratory Medicine, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan.

Isao Hidaka, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan.

Yoshio Marumoto, Center for Clinical Research, Yamaguchi University Hospital, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan.

Tsuyoshi Ishikawa, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan.

Naoki Yamamoto, Yamaguchi University Health Administration Center, Yamaguchi 753-8511, Japan.

Yutaka Suehiro, Department of Oncology and Laboratory Medicine, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan.

Taro Takami, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan.

Isao Sakaida, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi 755-8505, Japan.

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx.

- 2.Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer Collaboration, Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA, Allen C, Al-Raddadi R, Alvis-Guzman N, Amoako Y, Artaman A, Ayele TA, Barac A, Bensenor I, Berhane A, Bhutta Z, Castillo-Rivas J, Chitheer A, Choi JY, Cowie B, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dey S, Dicker D, Phuc H, Ekwueme DU, Zaki MS, Fischer F, Fürst T, Hancock J, Hay SI, Hotez P, Jee SH, Kasaeian A, Khader Y, Khang YH, Kumar A, Kutz M, Larson H, Lopez A, Lunevicius R, Malekzadeh R, McAlinden C, Meier T, Mendoza W, Mokdad A, Moradi-Lakeh M, Nagel G, Nguyen Q, Nguyen G, Ogbo F, Patton G, Pereira DM, Pourmalek F, Qorbani M, Radfar A, Roshandel G, Salomon JA, Sanabria J, Sartorius B, Satpathy M, Sawhney M, Sepanlou S, Shackelford K, Shore H, Sun J, Mengistu DT, Topór-Mądry R, Tran B, Ukwaja KN, Vlassov V, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wakayo T, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Yonemoto N, Younis M, Yu C, Zaidi Z, Zhu L, Murray CJL, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C. The Burden of Primary Liver Cancer and Underlying Etiologies From 1990 to 2015 at the Global, Regional, and National Level: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1683–1691. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tateishi R, Okanoue T, Fujiwara N, Okita K, Kiyosawa K, Omata M, Kumada H, Hayashi N, Koike K. Clinical characteristics, treatment, and prognosis of non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma: a large retrospective multicenter cohort study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:350–360. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0973-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urata Y, Yamasaki T, Saeki I, Iwai S, Kitahara M, Sawai Y, Tanaka K, Aoki T, Iwadou S, Fujita N, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma patients with modest alcohol consumption. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:434–442. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kudo M, Lencioni R, Marrero JA, Venook AP, Bronowicki JP, Chen XP, Dagher L, Furuse J, Geschwind JF, Ladrón de Guevara L, et al. Regional differences in sorafenib-treated patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: GIDEON observational study. Liver Int. 2016;36:1196–1205. doi: 10.1111/liv.13096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kudo M, Matsui O, Izumi N, Iijima H, Kadoya M, Imai Y, Okusaka T, Miyayama S, Tsuchiya K, Ueshima K, et al. JSH Consensus-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2014 Update by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Liver Cancer. 2014;3:458–468. doi: 10.1159/000343875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korean Liver Cancer Study Group (KLCSG); National Cancer Center, Korea (NCC) 2014 Korean Liver Cancer Study Group-National Cancer Center Korea practice guideline for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16:465–522. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yau T, Tang VY, Yao TJ, Fan ST, Lo CM, Poon RT. Development of Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system with treatment stratification for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1691–700.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omata M, Cheng AL, Kokudo N, Kudo M, Lee JM, Jia J, Tateishi R, Han KH, Chawla YK, Shiina S, et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 2017 update. Hepatol Int. 2017;11:317–370. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9799-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Japan Society of Hepatology. 2017. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (2017 version). Kanehara, Tolyo, Japan. Available from: https://www.jsh.or.jp/medical/guidelines/jsh_guidlines/examination_jp_2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verslype C, Rosmorduc O, Rougier P; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO-ESDO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23 Suppl 7:vii41–vii48. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benson AB 3rd, D’Angelica MI, Abbott DE, Abrams TA, Alberts SR, Saenz DA, Are C, Brown DB, Chang DT, Covey AM, Hawkins W, Iyer R, Jacob R, Karachristos A, Kelley RK, Kim R, Palta M, Park JO, Sahai V, Schefter T, Schmidt C, Sicklick JK, Singh G, Sohal D, Stein S, Tian GG, Vauthey JN, Venook AP, Zhu AX, Hoffmann KG, Darlow S. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Hepatobiliary Cancers, Version 1.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:563–573. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rimola J, Díaz-González Á, Darnell A, Varela M, Pons F, Hernandez-Guerra M, Delgado M, Castroagudin J, Matilla A, Sangro B, Rodriguez de Lope C, Sala M, Gonzalez C, Huertas C, Minguez B, Ayuso C, Bruix J, Reig M. Complete response under sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Relationship with dermatologic adverse events. Hepatology. 2017 doi: 10.1002/hep.29515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kudo M. Systemic Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2017 Update. Oncology. 2017;93 Suppl 1:135–146. doi: 10.1159/000481244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikeda M, Morizane C, Ueno M, Okusaka T, Ishii H, Furuse J. Chemotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: current status and future perspectives. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:103–114. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyx180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, Pracht M, Yokosuka O, Rosmorduc O, Breder V, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, Baron A, Park JW, Han G, Jassem J, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikeda K, Kudo M, Kawazoe S, Osaki Y, Ikeda M, Okusaka T, Tamai T, Suzuki T, Hisai T, Hayato S, et al. Phase 2 study of lenvatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:512–519. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1263-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruix J, Cheng AL, Meinhardt G, Nakajima K, De Sanctis Y, Llovet J. Prognostic factors and predictors of sorafenib benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Analysis of two phase III studies. J Hepatol. 2017;67:999–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Llovet JM, Peña CE, Lathia CD, Shan M, Meinhardt G, Bruix J; SHARP Investigators Study Group. Plasma biomarkers as predictors of outcome in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2290–2300. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyahara K, Nouso K, Morimoto Y, Takeuchi Y, Hagihara H, Kuwaki K, Onishi H, Ikeda F, Miyake Y, Nakamura S, et al. Pro-angiogenic cytokines for prediction of outcomes in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2072–2078. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuchiya K, Asahina Y, Matsuda S, Muraoka M, Nakata T, Suzuki Y, Tamaki N, Yasui Y, Suzuki S, Hosokawa T, et al. Changes in plasma vascular endothelial growth factor at 8 weeks after sorafenib administration as predictors of survival for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2014;120:229–237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Personeni N, Bozzarelli S, Pressiani T, Rimassa L, Tronconi MC, Sclafani F, Carnaghi C, Pedicini V, Giordano L, Santoro A. Usefulness of alpha-fetoprotein response in patients treated with sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;57:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yau T, Yao TJ, Chan P, Wong H, Pang R, Fan ST, Poon RT. The significance of early alpha-fetoprotein level changes in predicting clinical and survival benefits in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving sorafenib. Oncologist. 2011;16:1270–1279. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuzuya T, Ishigami M, Ishizu Y, Honda T, Hayashi K, Katano Y, Hirooka Y, Ishikawa T, Nakano I, Goto H. Early Clinical Response after 2 Weeks of Sorafenib Therapy Predicts Outcomes and Anti-Tumor Response in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakazawa T, Hidaka H, Takada J, Okuwaki Y, Tanaka Y, Watanabe M, Shibuya A, Minamino T, Kokubu S, Koizumi W. Early increase in α-fetoprotein for predicting unfavorable clinical outcomes in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:683–689. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835d913b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng YB, Zhao W, Liu B, Lu LG, He X, Huang JW, Li Y, Hu BS. The blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma receiving sorafenib. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:5527–5531. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.9.5527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howell J, Pinato DJ, Ramaswami R, Arizumi T, Ferrari C, Gibbin A, Burlone ME, Guaschino G, Toniutto P, Black J, et al. Integration of the cancer-related inflammatory response as a stratifying biomarker of survival in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Oncotarget. 2017;8:36161–36170. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shoji H, Yoshio S, Mano Y, Doi H, Sugiyama M, Osawa Y, Kimura K, Arai T, Itokawa N, Atsukawa M, et al. Pro-angiogenic TIE-2-expressing monocytes/TEMs as a biomarker of the effect of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:1011–1017. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stiuso P, Potenza N, Lombardi A, Ferrandino I, Monaco A, Zappavigna S, Vanacore D, Mosca N, Castiello F, Porto S, et al. MicroRNA-423-5p Promotes Autophagy in Cancer Cells and Is Increased in Serum From Hepatocarcinoma Patients Treated With Sorafenib. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e233. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoon EL, Yeon JE, Ko E, Lee HJ, Je JH, Yoo YJ, Kang SH, Suh SJ, Kim JH, Seo YS, et al. An Explorative Analysis for the Role of Serum miR-10b-3p Levels in Predicting Response to Sorafenib in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32:212–220. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishida N, Arizumi T, Hagiwara S, Ida H, Sakurai T, Kudo M. MicroRNAs for the Prediction of Early Response to Sorafenib Treatment in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2017;6:113–125. doi: 10.1159/000449475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Shi L, Zhang X, Sun B, Yang Y, Ge N, Liu H, Yang X, Chen L, Qian H, et al. pERK/pAkt phenotyping in circulating tumor cells as a biomarker for sorafenib efficacy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:2646–2659. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S, Amadori D, Santoro A, Figer A, De Greve J, Douillard JY, Lathia C, Schwartz B, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4293–4300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen D, Zhao P, Li SQ, Xiao WK, Yin XY, Peng BG, Liang LJ. Prognostic impact of pERK in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:974–980. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Negri FV, Dal Bello B, Porta C, Campanini N, Rossi S, Tinelli C, Poggi G, Missale G, Fanello S, Salvagni S, et al. Expression of pERK and VEGFR-2 in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and resistance to sorafenib treatment. Liver Int. 2015;35:2001–2008. doi: 10.1111/liv.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hagiwara S, Kudo M, Nagai T, Inoue T, Ueshima K, Nishida N, Watanabe T, Sakurai T. Activation of JNK and high expression level of CD133 predict a poor response to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1997–2003. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arao T, Ueshima K, Matsumoto K, Nagai T, Kimura H, Hagiwara S, Sakurai T, Haji S, Kanazawa A, Hidaka H, et al. FGF3/FGF4 amplification and multiple lung metastases in responders to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;57:1407–1415. doi: 10.1002/hep.25956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arizumi T, Ueshima K, Chishina H, Kono M, Takita M, Kitai S, Inoue T, Yada N, Hagiwara S, Minami Y, et al. Decreased blood flow after sorafenib administration is an imaging biomarker to predict overall survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis. 2014;32:733–739. doi: 10.1159/000368013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JH, Park JY, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Han KH, Seo HJ, Lee JD, Choi HJ. Prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET for hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Liver Int. 2011;31:1144–1149. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howell J, Pinato DJ, Ramaswami R, Bettinger D, Arizumi T, Ferrari C, Yen C, Gibbin A, Burlone ME, Guaschino G, et al. On-target sorafenib toxicity predicts improved survival in hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-centre, prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1146–1155. doi: 10.1111/apt.13977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shao YY, Hsu CH, Cheng AL. Predictive biomarkers of sorafenib efficacy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Are we getting there? World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10336–10347. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i36.10336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saeki I, Yamasaki T, Tanabe N, Iwamoto T, Matsumoto T, Urata Y, Hidaka I, Ishikawa T, Takami T, Yamamoto N, et al. A new therapeutic assessment score for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nouso K, Miyahara K, Uchida D, Kuwaki K, Izumi N, Omata M, Ichida T, Kudo M, Ku Y, Kokudo N, et al. Effect of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy of 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in the Nationwide Survey of Primary Liver Cancer in Japan. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1904–1907. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monden M, Sakon M, Sakata Y, Ueda Y, Hashimura E; FAIT Research Group. 5-fluorouracil arterial infusion + interferon therapy for highly advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter, randomized, phase II study. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:150–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim BK, Park JY, Choi HJ, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Kim JK, Lee DY, Lee KH, Han KH. Long-term clinical outcomes of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with cisplatin with or without 5-fluorouracil in locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:659–667. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0917-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamashita T, Arai K, Sunagozaka H, Ueda T, Terashima T, Yamashita T, Mizukoshi E, Sakai A, Nakamoto Y, Honda M, et al. Randomized, phase II study comparing interferon combined with hepatic arterial infusion of fluorouracil plus cisplatin and fluorouracil alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2011;81:281–290. doi: 10.1159/000334439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Obi S, Yoshida H, Toune R, Unuma T, Kanda M, Sato S, Tateishi R, Teratani T, Shiina S, Omata M. Combination therapy of intraarterial 5-fluorouracil and systemic interferon-alpha for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal venous invasion. Cancer. 2006;106:1990–1997. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ikeda M, Okusaka T, Furuse J, Mitsunaga S, Ueno H, Yamaura H, Inaba Y, Takeuchi Y, Satake M, Arai Y. A multi-institutional phase II trial of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with cisplatin for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;72:463–470. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iwasa S, Ikeda M, Okusaka T, Ueno H, Morizane C, Nakachi K, Mitsunaga S, Kondo S, Hagihara A, Shimizu S, et al. Transcatheter arterial infusion chemotherapy with a fine-powder formulation of cisplatin for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma refractory to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:770–775. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyr037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshikawa M, Ono N, Yodono H, Ichida T, Nakamura H. Phase II study of hepatic arterial infusion of a fine-powder formulation of cisplatin for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:474–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2008.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagano H, Wada H, Kobayashi S, Marubashi S, Eguchi H, Tanemura M, Tomimaru Y, Osuga K, Umeshita K, Doki Y, et al. Long-term outcome of combined interferon-α and 5-fluorouracil treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with major portal vein thrombosis. Oncology. 2011;80:63–69. doi: 10.1159/000328281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terashima T, Yamashita T, Iida N, Yamashita T, Nakagawa H, Arai K, Kitamura K, Kagaya T, Sakai Y, Mizukoshi E, et al. Blood neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a predictor in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy. Hepatol Res. 2015;45:949–959. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zaitsu J, Yamasaki T, Saeki I, Harima Y, Iwamoto T, Harima Y, Matsumoto T, Urata Y, Hidaka I, Marumoto Y, et al. Serum transferrin as a predictor of prognosis for hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:481–490. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niizeki T, Sumie S, Torimura T, Kurogi J, Kuromatsu R, Iwamoto H, Aino H, Nakano M, Kawaguchi A, Kakuma T, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor as a predictor of response and survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:686–695. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0555-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miyaki D, Aikata H, Honda Y, Naeshiro N, Nakahara T, Tanaka M, Nagaoki Y, Kawaoka T, Takaki S, Waki K, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma according to Child-Pugh classification. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1850–1857. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saeki I, Yamasaki T, Maeda M, Hisanaga T, Iwamoto T, Matsumoto T, Hidaka I, Ishikawa T, Takami T, Sakaida I. Evaluation of the “assessment for continuous treatment with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy” scoring system in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2018;48:E87–E97. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagamatsu H, Hiraki M, Mizukami N, Yoshida H, Iwamoto H, Sumie S, Torimura T, Sata M. Intra-arterial therapy with cisplatin suspension in lipiodol and 5-fluorouracil for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumour thrombosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:543–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagamatsu H, Sumie S, Niizeki T, Tajiri N, Iwamoto H, Aino H, Nakano M, Shimose S, Satani M, Okamura S, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemoembolization therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: multicenter phase II study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2892-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ikeda M, Shimizu S, Sato T, Morimoto M, Kojima Y, Inaba Y, Hagihara A, Kudo M, Nakamori S, Kaneko S, et al. Sorafenib plus hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with cisplatin versus sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: randomized phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:2090–2096. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kudo M, Ueshima K, Yokosuka O, Ogasawara S, Obi S, Izumi N, Aikata H, Nagano H, Hatano E, Sasaki Y, et al. Sorafenib plus low-dose cisplatin and fluorouracil hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus sorafenib alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (SILIUS): a randomised, open label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:424–432. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fujino H, Kimura T, Aikata H, Miyaki D, Kawaoka T, Kan H, Fukuhara T, Kobayashi T, Naeshiro N, Honda Y, et al. Role of 3-D conformal radiotherapy for major portal vein tumor thrombosis combined with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2015;45:607–617. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Onishi H, Nouso K, Nakamura S, Katsui K, Wada N, Morimoto Y, Miyahara K, Takeuchi Y, Kuwaki K, Yasunaka T, et al. Efficacy of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in combination with irradiation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein invasion. Hepatol Int. 2015;9:105–112. doi: 10.1007/s12072-014-9592-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hollebecque A, Cattan S, Romano O, Sergent G, Mourad A, Louvet A, Dharancy S, Boleslawski E, Truant S, Pruvot FR, et al. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma: the impact of the Child-Pugh score. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1193–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bruix J, Raoul JL, Sherman M, Mazzaferro V, Bolondi L, Craxi A, Galle PR, Santoro A, Beaugrand M, Sangiovanni A, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: subanalyses of a phase III trial. J Hepatol. 2012;57:821–829. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheng AL, Guan Z, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Yang TS, Tak WY, Pan H, Yu S, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma according to baseline status: subset analyses of the phase III Sorafenib Asia-Pacific trial. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1452–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kawaoka T, Aikata H, Hyogo H, Morio R, Morio K, Hatooka M, Fukuhara T, Kobayashi T, Naeshiro N, Miyaki D, et al. Comparison of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus sorafenib monotherapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Dig Dis. 2015;16:505–512. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fukubayashi K, Tanaka M, Izumi K, Watanabe T, Fujie S, Kawasaki T, Yoshimaru Y, Tateyama M, Setoyama H, Naoe H, et al. Evaluation of sorafenib treatment and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparative study using the propensity score matching method. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1214–1223. doi: 10.1002/cam4.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hatooka M, Kawaoka T, Aikata H, Morio K, Kobayashi T, Hiramatsu A, Imamura M, Kawakami Y, Murakami E, Waki K, et al. Comparison of Outcome of Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy and Sorafenib in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Refractory to Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:3523–3529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Terashima T, Yamashita T, Arai K, Kawaguchi K, Kitamura K, Yamashita T, Sakai Y, Mizukoshi E, Honda M, Kaneko S. Beneficial Effect of Maintaining Hepatic Reserve during Chemotherapy on the Outcomes of Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2017;6:236–249. doi: 10.1159/000472262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Terashima T, Yamashita T, Arai K, Kawaguchi K, Kitamura K, Yamashita T, Sakai Y, Mizukoshi E, Honda M, Kaneko S. Response to chemotherapy improves hepatic reserve for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and Child-Pugh B cirrhosis. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:1263–1269. doi: 10.1111/cas.12992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shiba S, Okusaka T, Ikeda M, Saito H, Ichida T. Characteristics of 18 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who obtained a complete response after treatment with sorafenib. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:1268–1276. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamasaki T, Sakaida I. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and future treatments for the poor responders. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:340–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miyaki D, Aikata H, Kan H, Fujino H, Urabe A, Masaki K, Fukuhara T, Kobayashi T, Naeshiro N, Nakahara T, et al. Clinical outcome of sorafenib treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma refractory to hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1834–1841. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yamasaki T, Terai S, Sakaida I. Deferoxamine for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:576–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1105726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yamasaki T, Saeki I, Sakaida I. Efficacy of iron chelator deferoxamine for hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients refractory to current treatments. Hepatol Int. 2014;8 Suppl 2:492–498. doi: 10.1007/s12072-013-9515-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kudo M. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Basics and Ongoing Clinical Trials. Oncology. 2017;92 Suppl 1:50–62. doi: 10.1159/000451016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, Kim TY, Choo SP, Trojan J, Welling TH Rd, Meyer T, Kang YK, Yeo W, Chopra A, Anderson J, Dela Cruz C, Lang L, Neely J, Tang H, Dastani HB, Melero I. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]