ABSTRACT

Background

In the past two decades, bats have emerged as an important model system to study host-pathogen interactions. More recently, it has been shown that bats may also serve as a new and excellent model to study aging, inflammation, and cancer, among other important biological processes. The cave nectar bat or lesser dawn bat (Eonycteris spelaea) is known to be a reservoir for several viruses and intracellular bacteria. It is widely distributed throughout the tropics and subtropics from India to Southeast Asia and pollinates several plant species, including the culturally and economically important durian in the region. Here, we report the whole-genome and transcriptome sequencing, followed by subsequent de novo assembly, of the E. spelaea genome solely using the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) long-read sequencing platform.

Findings

The newly assembled E. spelaea genome is 1.97 Gb in length and consists of 4,470 sequences with a contig N50 of 8.0 Mb. Identified repeat elements covered 34.65% of the genome, and 20,640 unique protein-coding genes with 39,526 transcripts were annotated.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that the PacBio long-read sequencing platform alone is sufficient to generate a comprehensive de novo assembled genome and transcriptome of an important bat species. These results will provide useful insights and act as a resource to expand our understanding of bat evolution, ecology, physiology, immunology, viral infection, and transmission dynamics.

Keywords: bat, Eonycteris spelaea, PacBio, Iso-Seq, genome assembly, alternative splicing

Data Description

Background

Unique among the mammalian species as they are the only order with true powered-flight capability, bats have served as a unique model for studying evolutionary adaptation and morphological innovations, such as flight, echolocation, and longevity [1, 2]. More recently, bats have been increasingly recognized as an important reservoir harboring numerous pathogenic viruses while displaying minimal clinical signs of disease [3]. Indeed, comparing the genomes of bats with the genomes of other mammalian species has revealed an unexpected concentration of positively selected genes. These include those involved in DNA damage repair and innate immune functions, which may partially explain bats’ unique tolerance to deadly viruses and their unusually long life span [4]. Together, this highlights bats as an emerging model organism in the study of ecology, development, aging, and evolution.

Accurate assembly and annotation of genomes is a critical first step for further functional studies of genetic variation. To date, there are 14 draft bat genomes that are published and deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (Eidolon helvum, Eptesicus fuscus, Hipposideros armiger, Megaderma lyra, Miniopterus natalensis, Myotis brandtii, Myotis davidii, Myotis lucifugus, Pteropus alecto, Pteronotus parnellii, Pteropus vampyrus, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, Rhinolophus sinicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus; Supplementary Table S1) [2, 4–7]. Most of these genomes were assembled using only short Illumina sequencing reads (49–150 bp), with the exception of R. aegyptiacus, which utilized both short reads (data not released) from the Illumina HiSeq platform and long reads (data not released) from the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) platform, resulting in a hybrid genome assembly. The long-read length of PacBio sequencing, which is available for both DNA and RNA sequencing (also known as isoform sequencing [Iso-Seq]), has shown considerable promise in genomics studies. For example, PacBio DNA sequencing has improved assembly of the human [8], gorilla [9], loblolly pine [10], and avian genomes [11], while Iso-Seq has helped deepen our understanding of alternative splicing in the chicken [12], coffee bean [13], and maize [14] transcriptomes.

To produce a reliable genome resource and more thoroughly annotated genome than that of other bats, we employed PacBio technology to sequence both the genome and transcriptome of the cave nectar bat (also known as common nectar bat, dawn bat, common dawn bat, and lesser dawn bat [Fig. 1]), Eonycteris spelaea (E. spelaea, NCBI taxonomy ID: 58 065). We hoped the PacBio long-read technology would facilitate accuracy in annotating this evolutionary divergent species. Eonycteris spelaea is a specialist nectar-feeding bat that feeds predominantly on nectar and pollen. It is widely distributed over both the tropics and subtropics, throughout the Indomalayan region [15–17]. This species has been associated with pollination of durian and other fruits of both cultural and economic importance throughout Asia [18]. Additionally, this species has been identified as a carrier of orthoreoviruses, Lyssa virus, filoviruses, flavivirus, coronaviruses, and astroviruses [19–26]. The spread and abundance of this species make it an ideal subject for research purposes.

Figure 1:

Female cave nectar bat (Eonycteris spelaea) with pup.

This newly assembled bat genome is 1.97 Gb in length, consisting of 4,470 sequences with a contig N50 of 8.0 Mbp. Identified repeat elements (REs) covered 34.65% of the genome, and 20,640 protein-coding genes were annotated. Also, 29,493 alternative spliceosomes for 10,607 genes were identified. Together, this resource and the identified regulatory elements provide information on the functional roles and relationships of various genomic loci, which in turn can be comparatively analyzed to further understand a vast array of bat-specific physiological features.

Sampling and sequencing

For whole-genome sequencing, 175 single-molecule real-time (SMRT) cells were sequenced. This yielded 15,518,413 (∼161 Gb) reads with a mean subread length of 10,381 bp (standard deviation [SD], 7,424) and a N50 read length of 14,941 bp (Table 1). This translated into an ∼80x coverage for the target genome (∼2 Gb in length, estimates based on the average size of all previously sequenced 14 bat genomes, Supplementary Fig. S1). The ∼80x coverage is above the minimum 50x–60x coverage reported for self-correction of the high-error PacBio reads compared to Illumina reads [27].

Table 1:

Data counts and library information for the E. spelaea genome

| Library type | Insert size, kb | No. of subreads | N50 size | Total bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA sequencing | 20 | 15 518 413 | 14 941 | 161 109 271 053 |

| Iso-Seq | 1–2 | 107 230 | 1 409 | 148 990 235 |

| 2–3 | 95 170 | 2 299 | 226 856 499 | |

| 3–6 | 104 687 | 3 700 | 403 584 865 | |

| 5–10 | 50 635 | 5 673 | 270 216 738 | |

| Total | 357 722 | 3 557 | 1 049 648 337 |

For Iso-Seq, 357,722 (∼1 Gb in total length) raw subreads (read length mean ± SD, 2934 ± 1775) were obtained (Table 1), representing an ∼20x coverage of the bat transcriptome repertoire (estimated using P. alecto’s 21,593 unique annotated genes, accounting for ∼0.05 Gb in length). After length-filtering and duplicate-collapsing (see Methods section), 31,639 unique full-length (FL) transcripts were used for subsequent analysis and gene annotation.

Genome assembly and evaluation

After several rounds of parameter adjustments with the Falcon (v. 0.3.0) algorithm (see Methods section), we obtained a final 1.97-Gb assembly (named Espe.v1), which consists of 4,470 sequences with a contig N50 of 8.0 Mb (Table 2). We employed the Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) (v. 3) method [28] to evaluate the completeness of the genome annotation. The result showed that the vast majority (92.8%) of the representative mammal gene set (mammalia_odb9, which contains 4,104 single-copy genes that are highly conserved in mammals) was present in the assembled bat genome, demonstrating the completeness of gene set identification (Table 2). The Guanine-Cytosine (GC) content was 40.3%, similar to those of P. alecto (39.7%) and R. aegyptiacus (40.2%, Table 2). Overall, these metrics compare well with other recently published bat genomes, confirming Espe.v1 to be a reliable substrate for further genomic analyses.

Table 2:

Comparison of genome features among E. spelaea, P. alecto, and R. aegyptiacus

| Type | E. spelaea | P. alecto | R. aegyptiacus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing technology | PacBio | Illumina HiSeq | Illumina HiSeq + PacBio |

| Genome coverage | ∼83x | ∼110x | ∼169x |

| Total genome length (bp) | 1 966 861 576 | 1 985 975 446 | 1 910 250 568 |

| Number of Contigs/scaffold | 4 470/N.A. | 170 164/65 598 | 3 049/2 490 |

| Contigs/scaffold N50 (bp) | 8 002 591/N.A. | 31 841/15 954 802 | 1 488 988/2 007 187 |

| GC level | 40.3% | 39.7% | 40.02% |

| Repetitive elementsa | 34.65% | 30.08% | 29.58% |

| Number of coding genes | 20,640 | 18,363 | 19,668 |

| b (n = 4104) | C:92.8%,F:4.8%,M:2.4% | C:94.1%,F:3.7%,M:2.2% | C:93.5%,F:4.4%,M:2.1% |

aKnown mammalian repetitive elements deposit in Repbase (Update 20 160 829).

bBUSCO: Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs; C: complete BUSCOs; F: fragmented BUSCOs; M: missing BUSCOs; N.A. not available.

Genome annotation

RepeatMasker (v. 4.0.6) [29] was conducted with RMBlast (v. 2.2.28) to mask all the known mammalian transposon-derived REs. In order to compare the REs of E. spelaea with those of other genomes, we also performed the same analysis on all 14 available bat genomes on NCBI. Consistent with observations that PacBio technology is a better solution for solving repeats [8, 27], we found that known REs accounted for 34.65% of the genome in Espe.v1, which is the highest proportion among all bat genomes published to date (0.71% higher than that of the second RE-abundant bat genome, R. sinicus; Table 2, Supplementary Fig. S1). Similar to other bat genomes, the long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) and long terminal repeat elements constituted two of the highest proportion of all REs in Espe.v1, 51.32% and 18.05%, respectively (Supplementary Table S2).

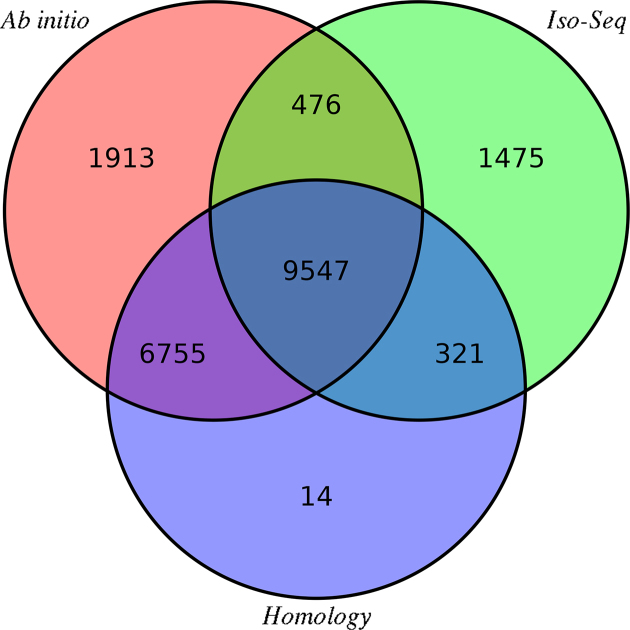

After repeat masking, the genome was annotated with Maker2 (v. 2.31.9) [30] by integrating homologous prediction, ab initio prediction, and Iso-Seq-based prediction methods (see Methods section). As a result, the predicted gene set included 20,640 protein-coding genes (Fig. 2), of which 11,819 (57.2%) unique coding genes were supported by Iso-Seq and 16,637 (80.6%) were supported by homologous predictions. The relatively higher number of protein-coding genes predicted in E. spelaea compared to P. alecto and R. aegyptiacus is likely due to a more homologous approach being used to predict the gene models of E. spelaea than that of P. alecto and R. aegyptiacus (see Methods section). In summary, 18,588 (90.1%) of the coding genes were supported by at least one of the two types of prediction evidence (homologous and Iso-Seq evidence).

Figure 2:

Venn diagram for coding gene predictions based on evidence sources. The different colors indicate various sources of evidence, and the values reflect the number of genes supported by each type of evidence.

Phylogenetic analysis

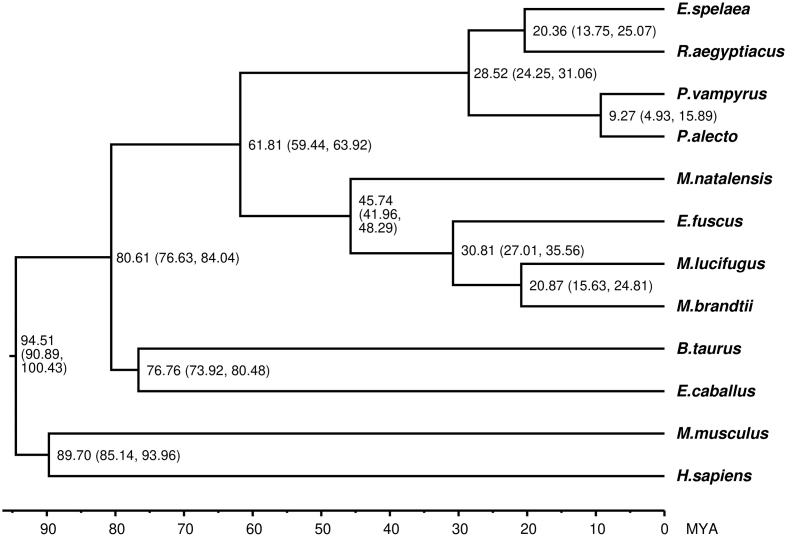

To evaluate the similarities and differences of available bat genomes and their evolutionary relationship, it is necessary to compare the phylogenies of E. spelaea to those of other bats and other mammalian species. Despite significant biological differences in the behaviors of bats, genetically some species are phylogenetically close, and this may impact any study of the homology between species. We identified single-copy orthologous gene clusters from 13 published genomes (8 bat genomes: M. brandtii, M. lucifugus, M. davidii, E. spelaea, E. fuscus, P. alecto, P. vampyrus, and R. aegyptiacus and 5 other mammalian genomes: Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Bos taurus, and Equus caballus and Monodelphis domestica; with M. domestica as the outgroup; Supplementary Table S1) using the Proteinortho software [31]. In total, 3,185 single-copy gene families across all 13 species were identified.

The divergence times of E. spelaea and the 11 mammals (excluding M. domestica) were estimated using 999,609 4-fold degenerate sites from the 3,185 single-copy genes. The topological order and estimated divergence time of our phylogeny analysis (Fig. 3) are consistent with those from previous studies [4, 32], with bats, E. caballus (horse), and B. taurus (cow) clustering together within the Laurasiatheria superorder (bats diverging ∼80.61 million years ago [Mya) [4]. Our analysis also revealed that E. spelaea was the closest sister taxon to R. aegyptiacus, an Egyptian fruit bat that is distributed throughout Africa [33]. The divergence time between these two bat species was estimated at ∼20.36 Mya, indicating a relatively recent divergence. As P. alecto, R. aegyptiacus, and E. spelaea are all relatively close on the phylogenetic tree and all have reliable genome annotations, we focus on these three species for a more detailed comparison.

Figure 3:

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis of 3,185 genes in bats and mammalian species. The estimated divergence time (100 Mya) is given at the nodes, with the 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. Monodelphis domestica, used as an outgroup species, was excluded in this figure.

Iso-Seq analysis

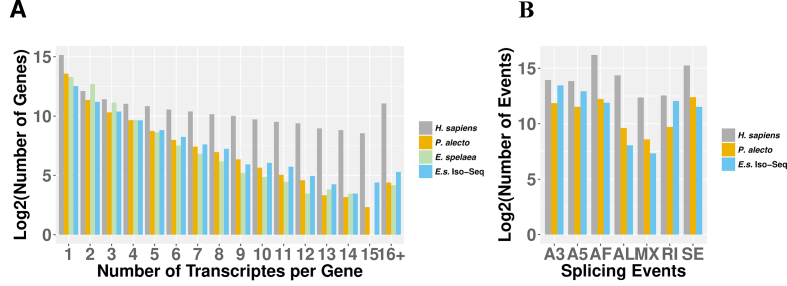

A major advantage of Iso-Seq technology is that it captures FL gene isoforms without the need for any downstream assembly. The large number of unique transcripts recovered through Iso-Seq enabled us to make a general assessment of transcriptional complexity of the bat genome. Of the 31,639 FL Iso-Seq transcripts, 382 RE transcripts (98 LTRs, 31 DNA elements, 7 satellites, 244 LINEs, 1 short interspersed nuclear element, and 1 unknown RE) were filtered out from further analysis using RepeatMasker (see Methods section). The remaining 31,257 clean transcripts were compared against our homology and ab initio predicted genes. Of the 20,640 coding genes, we observed 10,033 (5,925 are supported by clean Iso-Seq transcripts) single transcript genes and 10,607 (5,894 are supported by clean Iso-Seq transcripts) alternatively spliced genes. Overall, we found an isoform-to-gene ratio of 1.92 (39,526 transcripts per 20,640 genes) in E. spelaea, which is lower than 3.62 (167,430 transcripts per 46,298 genes) in human, but higher than 1.49 (33,093 transcripts per 22,264 genes) in P. alecto (Fig. 4A). When narrowed down to genes only observed by Iso-Seq, we found an isoform-to-gene ratio of 2.39 (28,289 transcripts per 11,819 genes), suggesting that PacBio Iso-Seq technology has significantly increased the isoform diversity discovery of E. spelaea’s transcriptome compared to that of P. alecto’s transcriptome, which was sequenced using the Illumina RNA-Seq technology (Fisher exact test, P value < 10−5).

Figure 4:

The alternative splicing of E. spelaea’s coding genes. (A) Comparison of number of alternative transcripts per annotated gene between H. sapiens, P. alecto, E. spelaea, and PacBio Iso-Seq E. spelaea transcriptomes. (B) Comparison of rate of occurrence for the different classes of alternative transcripts between H. sapiens, P. alecto, and the E. spelaea PacBio Iso-Seq transcriptome. Abbreviations: A5/A3: alternative 5′/3′ splice sites; AF/AL: alternative first/last exons; MX: mutually exclusive exons; RI: retained intron; SE: skipping exon.

The alternative transcript events were further classified into skipping exon, alternative 5′/3′ splice sites, mutually exclusive exons, retained intron, and alternative first/last exons by SUPPA software (last updated 02/07/2017) [34]. We identified 30,487 alternative splicing events in the Iso-Seq dataset, which is 5.80-fold lower than that in human but 1.62-fold higher than that in P. alecto (Fig. 4B). In particular, alternative 5’- (7,783 events) and 3’- (11,258 events) splicing were two of the most predominant events in the E. spelaea spliceosome repertoire (Fig. 4B). Our results provide the first comprehensive overview of splice variants in any bat species using a direct sequencing analysis approach rather than in silico analysis.

Conclusions and discussion

In this study, we provided the first assembly of a bat genome solely using PacBio long-read sequencing technology. The E. spelaea genome assembly exemplifies the power of long-read sequencing technologies in rapid de novo assembly of a nonmodel genome and alternative-splicing isoform identification. Compared to the hybrid assembled R. aegyptiacus genome, the “PacBio-only” assembly was faster, more straightforward, and possessed higher contiguous N50 contigs and better repeat-resolving with a minimum difference (0.7%) in gene integrity. Thus, our study provides a high-quality reference genome for use in any future comparative studies. Even without scaffolding, these highly contiguous contigs and FL gene transcripts will be helpful to researchers to extract more accurate genomic loci information of their genes of interest, saving a great amount of energy, resources, and time. Our Iso-Seq results have increased our understanding of the complexity of the bat transcriptome and aided in alternative transcript identification. This complexity in the transcriptome of bats is still likely to be underestimated since Iso-Seq was performed at a relatively shallow depth (∼20x coverage) in this study. We would like to further highlight that this complexity is attributed by the type and number of alternative transcription events, as well as previously unannotated transcripts in bats. As more and more transcriptome data become available for E. spelaea, e.g., Illumina transcriptome sequencing of various tissues, this will aid in the identification of other alternative transcripts and continuously improve the annotation of the genome and the accuracy of protein coding sequences, as has been evident with the P. alecto genome since its first release. Taken together, we have provided a valuable resource, an E. spelaea genome and transcriptome database, for future comparative and functional studies, as well as demonstrated the advantages of employing the latest long-read sequencing technology in such studies of exotic species.

Methods

Bat sample processing

Eonycteris spelaea was captured in Singapore at dusk using mist nets and transferred to clean customized bat bags for transportation. All animal processing work was conducted in accordance with approved guidelines and methods in line with permits obtained from the National Parks Board, Singapore (NP/RP14–109) and animal ethics approval from the National University of Singapore (B16–0159). Bats were euthanized using isoflurane and exsanguinated via cardiac bleed. Various tissue samples, as detailed in Supplementary Table S3, were harvested and preserved in RNAlater stabilization solution (Invitrogen). Tissues were homogenized, and RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) with an additional on-column DNase digestion step using RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen). Extracted RNA was subsequently eluted in RNase-Free water and stored at –80 °C.

For genomic DNA extraction, fresh lung and kidney samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately upon harvesting and pounded into powder form before extraction using the Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit (Qiagen).

DNA and Iso-Seq sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from a single male E. spelaea. Two DNA libraries, derived from kidney and lung samples, were constructed using SMRTbell Template Prep Kits 1.0 (Pacific Biosciences) with a 20 kb insert size. SMRT sequence data were generated using P6v2 polymerase binding and C4 chemistry (P6-C4) kits over a 6-hour movie run-time on the PacBio RSII instrument. Library construction and sequencing runs were performed by a commercial sequencing provider DNA Link Inc. (Korea).

For Iso-Seq sequencing, total RNA from a panel of tissues (Supplementary Table S3) was extracted from two individuals, a female and a male. Tissue RNA from individual bats was then pooled together. Four libraries of 1–2 kb, 2–3 kb, 3–6 kb, and 5–10 kb insert sizes were generated using the P6-C4 kits and subsequently sequenced. In total, 34 SMRT cells were sequenced on the PacBio RS II platform over a 3- to 4-hour movie run time. Library construction and Iso-Seq runs were performed at the Duke-NUS Genome Biology Facility (Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore).

Genome assembly

PacBio subreads were filtered with default parameters and submitted to Falcon ([35], v. 0.3.0) for genome assembly. For the final assembly (Espe.v1), 15,518,413 subreads (read length mean ± SD, 10,382 ± 7,424) were used for assembly, with a length-cutoff parameter of 2 kb for initial mapping to build pre-assembled reads (also referred to as error-corrected preads). The pre-assembly module is a built-in module in Falcon for error-correcting PacBio subreads. A total of 15,470,844 preads were generated (read length mean ± SD, 7,034 ± 5,874) from the PacBio subreads. Preads over 10 kb were used (length-cutoff-pr) to seed pre-assembly. Daligner was used to detect all pairwise local overlapping regions between subreads and also between corrected preads. Overlapping options were set to “-v -B128 -M40 -e.70 -l2000 -s400” for pre-assembly and “-v -B128 -M40 -h45 -e.96 -l500 -s400” for alignment of corrected preads. To reduce computation and assembly graph complexity, overlaps built by corrected preads were filtered by “–max-diff 300 –max-cov 400 –min-cov 2 –bestn 20” to remove the transitive reducible overlaps. Consensus was built from the overlapping preads on “–output-multi –min-idt 0.70 –min-cov –max-n-read 400.” Finally, primary and associated contigs were polished using Quiver with default parameters.

Iso-Seq analysis

For Iso-Seq analysis, raw reads were classified into circular consensus sequences (CCS) and non-CCS subreads by ToFu (v. 4.1) [36], and FL CCS reads were filtered out if both the 5′- and 3′-cDNA primers were present, as well as a polyA tail signal preceding the 3′-primer. To improve consensus accuracy, the isoform-level clustering algorithm (iterative clustering for error correction) and Quiver were applied to generated FL transcripts with ≥99% post-correction accuracy. Next, the Quiver-polished FL CCS reads were mapped to the assembled genome using GMAP (v. 2018–01-26) [37] and collapsed by the pbtranscript-ToFU package ([38], last updated: 10/15/2015) with default parameters to collapse redundant transcripts. Collapsed transcripts were screened for REs by RepeatMasker (v. open-4.0.6) [39] to mask all mammalian RE sequences. Transcripts with ≥70% bases masked were denoted as REs and discarded from further analysis. Alternative splicing events in the repeat-cleaned Iso-Seq reads, human (Ensembl GRCh38.p10), and P. alecto (NCBI assembly ASM32557v1) mRNAs were classified with SUPPA (last updated 02/07/2017) under default parameters.

Genome annotation

Maker2 (v. 2.31.9) [30] was utilized to perform genome annotation. Repetitive genomic elements were identified and masked from annotation with RepeatMasker using the Repbase database (Update 20 160 829) [40]. Cleaned Iso-Seq transcripts (see above) were used as transcript evidence. Augustus (v. 2.7) [41] and SNAP (release 11/29/2013) [42] were used as ab initio gene predictors. Unique protein sequences from eight different mammals (B. taurus, Canis familiaris, E. caballus, H. sapiens, M. musculus, M. lucifugus, P. alecto, P. vampyrus; Supplementary Table S1) were downloaded from Ensembl (last accessed: 5/15/2017) [43] and used for homology-based prediction. The Maker2 pipeline was first run on the masked genome using the Iso-Seq transcriptome to infer gene predictions (est2genome = 1), and training files for the ab initio gene predictors Augustus and SNAP were generated based on these results. Then, the annotation pipeline was run iteratively two additional times using the Iso-Seq transcriptome as evidence (est2genome = 0) and providing new training files with each run. At this point, the protein-homology evidence was set to include all unique proteins in the eight different mammals. Next, Maker predict transcripts were merged with Iso-Seq transcripts and collapsed using pbtranscript-ToFU to include all the unique alternative spliced transcripts. Finally, low-quality genes shorter than 50 amino acids and/or exhibiting premature termination were removed to produce the final gene set.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic tree construction and divergence time estimation were performed as described in [4]. Briefly, Proteinortho software (v. 5.16b) [31] was used to identify the single-copy orthologous genes under default parameter setting. Using M. domestica as an outgroup, we identified 3,185 single-copy orthologous genes from E. spelaea and 11 other mammalian genomes (as described above). The coding sequence from each single-copy family was aligned by MUSCLE (v. 3.8.31) [44]. Four-fold degenerate sites were extracted from each gene alignment by an in-house Python script and concatenated to one super gene for each species. Then, RAxML (v. 8.2.11) [45] was applied to build phylogenetic trees for the concatenated sequences as described [4]. A total of 1,000 bootstrap replicates were employed to assess branch reliability in RAxML. Last, PAML (v. 4.9c) mcmctree [46] was used to determine split times based on the topology obtained in the RAxML analysis [4]. The gamma prior for the overall substitution rate was described by shape and scale parameters that were set as 1 and 11.1, respectively, calculated according to the substitution rate per time unit using PAML baseml [47]. Fossil calibrations were retrieved from the TimeTree database (last accessed 12/15/2017) [48]. Other parameters were set as default. The PAML mcmctree pipeline was run two independent times to confirm convergence and all acceptance proportions fall in the interval (20%, 40%).

Availability of supporting data

Genome data are available in the NCBI database ( project accession PRJNA427241). Further supporting data can be found in the GigaScience repository, GigaDB [49].

Additional files

Figure S1: Scatter plot of the genome size and proportion of repeat content for 15 bats genomes.

Table S1: Reference genomes used in this study.

Table S2: Descriptive statistics of the E. spelaea genome repeat elements using RepeatMasker. RepBase Update 20 160 829.

Table S3: Detailed listing of E. spelaea tissue RNA used for Iso-Seq analysis

Abbreviations

BUSCO: Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs; CCS: circular consensus sequence; FL: full-length; GC: Guanine-Cytosine; Iso-Seq: isoform sequencing; LINE: long interspersed nuclear element; Mya: million years ago; NCBI: National Center for Biotechnology Information; P6-C4: P6v2 polymerase binding and C4 chemistry; PacBio: Pacific Biosciences; RE: repeat element; SD: standard deviation; SMRT: single-molecule real-time.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was funded by the Singapore National Research Foundation Competitive Research Programme (grant NRF2012NRF-CRP001–056). A.T.I. is supported by a New Investigator's Grant from the National Medical Research Council of Singapore (NMRC/BNIG/2040/2015). I.H.M. was supported by a New Investigator's Grant from the National Medical Research Council of Singapore (NMRC/BNIG/2005/2013). B.P.Y-H.L. was supported by a research grant from the Wildlife Reserves Singapore Conservation Fund (WRSCF).

Author contributions

L-F.W. and J.H.J.N. conceived and designed the study; I.H.M., B.P.Y-H.L., C.Y.T., A.T.I and J.H.J.N. led the bat field work; C.Y.T. and J.H.J.N. performed the experimental processing of samples; M.W. and F.Z. led the sequence analysis; and F.Z. and A.T.I. contributed to data analysis. All authors contributed to manuscript writing, reviewing, and approval of the final version for submission.

Supplementary Material

4/20/2018 Reviewed

4/24/2018 Reviewed

5/1/2018 Reviewed

4/20/2018 Reviewed

8/3/2018 Reviewed

8/5/2018 Reviewed

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by the Singapore National Research Foundation Competitive Research Programme (grant NRF2012NRF-CRP001–056). A.T.I. is supported by a New Investigator's Grant from the National Medical Research Council of Singapore (NMRC/BNIG/2040/2015). I.H.M. was supported by a New Investigator's Grant from the National Medical Research Council of Singapore (NMRC/BNIG/2005/2013). B.P.Y-H.L. was supported by a research grant from the Wildlife Reserves Singapore Conservation Fund (WRSCF). We thank Dolyce Low Hong Wen, Erica Sena Neves, and Sophie Alison Borthwick for their help with bat fieldwork; the Duke-NUS Genome Biology Facility and the Genome Institute of Singapore for library construction, quality control, sequencing, and data delivery; and the Duke-NUS High Performance Computing Infrastructure for computational resources.

References

- 1. Simmons NB, Seymour KL, Habersetzer J, et al. Primitive early eocene bat from Wyoming and the evolution of flight and echolocation. Nature. 2008;451(7180):818–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seim I, Fang X, Xiong Z, et al. Genome analysis reveals insights into physiology and longevity of the Brandt's bat Myotis brandtii. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olival KJ, Hosseini PR, Zambrana-Torrelio C, et al. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature. 2017;546(7660):646–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang G, Cowled C, Shi Z et al. Comparative analysis of bat genomes provides insight into the evolution of flight and immunity. Science. 2013;339(6118):456–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eckalbar WL, Schlebusch SA, Mason MK et al. Transcriptomic and epigenomic characterization of the developing bat wing. Nat Genet. 2016;48(5):528–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dong D, Lei M, Hua P et al. The genomes of two bat species with long constant frequency echolocation calls. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34(1):20–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parker J, Tsagkogeorga G, Cotton JA, et al. Genome-wide signatures of convergent evolution in echolocating mammals. Nature. 2013;502(7470):228–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pendleton M, Sebra R, Pang AW, et al. Assembly and diploid architecture of an individual human genome via single-molecule technologies. Nat Methods. 2015;12(8):780–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gordon D, Huddleston J, Chaisson MJ et al. Long-read sequence assembly of the gorilla genome. Science. 2016;352(6281):aae0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zimin AV, Stevens KA, Crepeau MW et al. An improved assembly of the loblolly pine mega-genome using long-read single-molecule sequencing. GigaScience. 2017;6(1):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Korlach J, Gedman G, Kingan SB et al. De novo PacBio long-read and phased avian genome assemblies correct and add to reference genes generated with intermediate and short reads. GigaScience. 2017;6(10):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuo RI, Tseng E, Eory L, et al. Normalized long read RNA sequencing in chicken reveals transcriptome complexity similar to human. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cheng B, Furtado A, Henry RJ. Long-read sequencing of the coffee bean transcriptome reveals the diversity of full-length transcripts. GigaScience. 2017;6(11):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang B, Tseng E, Regulski M, et al. Unveiling the complexity of the maize transcriptome by single-molecule long-read sequencing. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ghanem SJ, Voigt CC. Increasing awareness of ecosystem services provided by bats. Advances in the Study of Behavior. 2012;44:279–302. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shao WW, Hua PY, Zhou SY et al. Characterization of microsatellite loci in the lesser dawn bat (Eonycteris spelaea). Mol Ecol Resour. 2008;8(3):695–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Francis CM, Barrett P. A Guide to the Mammals of Southeast Asia. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bumrungsri S, Sripaoraya E, Chongsiri T et al. The pollination ecology of durian (Durio zibethinus, Bombacaceae) in southern Thailand. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 2009;25(1):85–92. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laing ED, Mendenhall IH, Linster M et al. Serologic evidence of fruit bat exposure to filoviruses, Singapore, 2011–2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(1):114–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mendenhall IH, Borthwick S, Neves ES et al. Identification of a lineage D betacoronavirus in cave nectar bats (Eonycteris spelaea) in Singapore and an overview of lineage D reservoir ecology in SE Asian bats. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2017;64(6):1790–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mendenhall IH, Skiles MM, Neves ES, et al. Influence of age and body condition on astrovirus infection of bats in Singapore: an evolutionary and epidemiological analysis. One Health. 2017;4:27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang XL, Zhang YZ, Jiang RD et al. Genetically diverse filoviruses in rousettus and eonycteris spp. bats, China, 2009 and 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(3):482–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kapoor A, Simmonds P, Lipkin WI, et al. Use of nucleotide composition analysis to infer hosts for three novel picorna-like viruses. J Virol. 2010;84(19):10322–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lumlertdacha B, Boongird K, Wanghongsa S, et al. Survey for bat lyssaviruses, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(2):232–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taniguchi S, Maeda K, Horimoto T et al. First isolation and characterization of pteropine orthoreoviruses in fruit bats in the Philippines. Arch Virol. 2017;162(6):1529–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Varelas-Wesley I, Calisher CH. Antigenic relationships of flaviviruses with undetermined arthropod-borne status. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31(6):1273–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berlin K, Koren S, Chin CS et al. Assembling large genomes with single-molecule sequencing and locality-sensitive hashing. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(6):623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Simao FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P et al. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(19):3210–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2009, 25, 1, 4.10.1–4.10.14.;Chapter 4:Unit 4 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Holt C, Yandell M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics, 2011;12:491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lechner M, Findeiß S, Steiner L, et al. Proteinortho: detection of (co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bhak Y, Jeon Y, Jeon S, et al. Myotis rufoniger genome sequence and analyses: M. rufoniger's genomic feature and the decreasing effective population size of Myotis bats. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lučan RK, Bartonička T, Benda P, et al. Reproductive seasonality of the Egyptian fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus) at the northern limits of its distribution. J Mammal. 2014;95(5):1036–42. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alamancos GP, Pagès A, Trincado JL et al. Leveraging transcript quantification for fast computation of alternative splicing profiles. RNA. 2015;21(9):1521–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. FALCON GitHub page https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/FALCON.

- 36. Gordon SP, Tseng E, Salamov A et al. Widespread polycistronic transcripts in fungi revealed by single-molecule mRNA sequencing. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wu TD, Watanabe CK. GMAP: a genomic mapping and alignment program for mRNA and EST sequences. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(9):1859–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scripts for processing PacBio Transcriptome (Iso-Seq) data. December 2017 http://github.com/PacificBiosciences/cDNA_primer/, Scripts for processing PacBio Transcriptome (Iso-Seq) data. Accession Date: December 2017.

- 39. Smit A, Hubley R, Green P. RepeatMasker Open-4.0. 2015. http://repeatmasker.org. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bao W, Kojima KK, Kohany O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob DNA. 2015;6:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stanke M, Steinkamp R, Waack S, et al. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene finding in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W309–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zerbino DR, Achuthan P, Akanni W, et al. Ensembl 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;46(D1):D754–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. dos Reis M, Yang Z. Approximate likelihood calculation on a phylogeny for Bayesian estimation of divergence times. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(7):2161–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(8):1586–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hedges SB, Dudley J, Kumar S. TimeTree: a public knowledge-base of divergence times among organisms. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(23):2971–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wen M, J Ng JH, Zhu F et al. Supporting data for “Exploring the genome and transcriptome of the cave nectar bat Eonycteris spelaea with PacBio long-read sequencing.” GigaScience Database. 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.5524/100500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

4/20/2018 Reviewed

4/24/2018 Reviewed

5/1/2018 Reviewed

4/20/2018 Reviewed

8/3/2018 Reviewed

8/5/2018 Reviewed