Abstract

Background:

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) reflects a patient’s perceived disease burden, treatment effectiveness, and health status. Given the time burden and physiologic effects of hemodialysis, patients who spend dialysis time (9–15 hours/week) physically or intellectually engaged may have better HRQOL. We characterized the intradialytic activities and explored their association with HRQOL.

Methods:

In a cross-sectional study of 431 hemodialysis patients we ascertained kidney disease quality of life, measured frailty, and surveyed participants about their usual active intradialytic activities (reading, playing games, doing puzzles, chatting or other) and passive intradialytic activities (watching TV or sleeping). We used adjusted ordered logistic regression to identify correlates of the activity index (the sum of active intradialytic activities) and adjusted linear regression to quantify the association between the activity index and physical, mental, and kidney-disease specific HRQOL.

Results:

The two most common intradialytic activities were passive [watching TV=87.9%; sleeping=72.4%]. Participants who were female (aOR=1.85, 95%CI:1.28,2.66; p=0.001), nonfrail (aOR=1.70, 95%CI:1.06–2.70; p=0.03), and nonsmokers (aOR=2.61, 95%CI:1.39,4.90; p=0.003) had a higher intradialytic activity index after adjustment. Higher intradialytic activity index was associated with better mental (+0.83 points, 95%CI: +0.04,+1.62; p=0.04) and kidney disease-specific HRQOL (+1.70 points, 95%CI: +0.47,+2.93; p=0.007), but not physical HRQOL.

Conclusions:

Hemodialysis patients with more active intradialytic activities report better mental and kidney disease-specific HRQOL. These results should be confirmed in a prospective study with a broader cohort of hemodialysis patients. Dialysis providers may consider offering patients with low levels of activity additional support and opportunities to engage in beneficial intradialytic activities.

Keywords: hemodialysis, intradialytic activities, HRQOL

INTRODUCTION

Patients undergoing hemodialysis are especially prone to impairments in health-related quality of life (HRQOL), a multidimensional construct that reflects a patient’s perceived disease burden, treatment effectiveness, and overall health status (1). Because HRQOL accounts for the clinical manifestation of disease, the side effects of treatments, and the support of family members and healthcare providers, it is an important patient-centered outcome for patients undergoing hemodialysis. In addition to a marker of overall wellbeing, HRQOL is also a salient predictor of healthcare utilization and clinical outcomes. Among patients undergoing hemodialysis, poor physical HRQOL is associated with 1.09-fold increased risk of hospitalization and 1.21-fold increased risk of mortality (2). Similarly, poor mental and kidney-disease specific HRQOL are also associated with significantly increased risks of hospitalization and mortality, indicating that all three domains of HRQOL are important predictors of adverse health events (2,3).

Given that hemodialysis treatment requires that patients are connected to a dialyzer for 3 to 5 hours at least three times a week, and the profound physiologic and cognitive toll of hemodialysis (2,4–7), it is likely that patients who spend dialysis time more actively engaged have better HRQOL. However, little is known about the array of intradialytic activities patients perform. The majority of studies of intradialytic activities have been qualitative studies (8,9) and clinical trials (10–14) that evaluate whether implementing exercise training, brain games, and nutritional support regimens during dialysis ameliorate dialysis-related symptoms. A growing body of literature suggests that such discretionary activities are safe, feasible to administer, and may have beneficial effects on HRQOL (8,15). However, there is little known about the typical intradialytic activities that would be replaced by such interventions or whether the willingness of hemodialysis patients to participate in intradialytic interventions differs by how active they are while undergoing hemodialysis.

To better understand the intradialytic activities of patients undergoing hemodialysis, the association between intradialytic activity and HRQOL, as well as the interest of patients in performing potentially beneficial intradialytic interventions, we conducted a cross-sectional study of 431 patients undergoing hemodialysis. The primary objectives of this study were to: 1) characterize the activities patients perform during dialysis, 2) quantify the association between intradialytic activity and physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL, and 3) understand willingness to perform intradialytic physical exercise and cognitive training.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

We leveraged a cohort study of 431 hemodialysis patients enrolled in a longitudinal study of frailty and kidney transplantation prior to listing for kidney transplantation. Participants were English-speaking patients aged 18 years and older who were evaluated for kidney transplantation at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland from October 2016 to December 2017; their selection for listing was not based on their response during this research study. In this cross-sectional study, we ascertained intradialytic activity, HRQOL, and willingness to perform intradialytic intervention at the time of evaluation as described below. Demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, employment status, and smoking status) were assessed at the time of enrollment. Additional clinical factors (body mass index [BMI], dialysis vintage) which were abstracted from medical records. A Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) adapted for patients with ESRD was calculated from comorbidities in the medical record at the time of enrollment (16). As described below, we ascertained each participant’s frailty status, their depressive symptoms, and their leisure time activities. The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent. This research is in adherence with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Intradialytic Activity

We ascertained intradialytic activity, the primary exposure in this study, by surveying participants about the activities they typically perform during dialysis. Participants responded verbally to the question: “What do you normally do on dialysis?” by responding “yes” or “no” to the following activities: Read, Play electronic games, Do Puzzles, Watch TV, Sleep, Talk/Chat. Participants were also able to respond Other and provide a description of one or multiple additional activities. We created an activity index on a scale of 0- to 5-points. Active intradialytic activities (Read, Play electronic games, Puzzles, Chat, Other [physical or cognitive activity] were assigned one point each. Passive intradialytic activities (Watch TV, Sleep, Other [non-physical or non-cognitive activity]) were assigned zero points. Higher scores on the intradialytic activity index reflect more active intradialytic activities.

Frailty, Depressive Symptoms, and Leisure Time Activities

We ascertained depressive symptoms at KT admission using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), a 20-item questionnaire that queries depressive symptoms over the past week (17), and leisure time activities over the last two weeks was ascertained by the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activities Questionnaire (18). We additionally studied the physical frailty phenotype as defined by Fried et al in older adults (19) and by our group in ESRD and KT populations (4,7,20–30), which is comprised of 5 components which were measured at the same time as the intradialytic activities: slowed gait speed (walking time of 15 feet below an established cutoff by gender and height), weakness (grip strength below an established gender-and BMI- based cutoff), exhaustion (self-report using two items from the CES-D), shrinking (self-report of unintentional weight loss of more than 10 pounds in the past year based on dry weight), and low physical activity (kilocalories/week below an established cutoff based on the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activities Questionnaire) (19).

Health-Related Quality of Life

We assessed health-related and kidney disease-specific quality of life using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument short form (KDQOL) version 1.3 (31,32). The KDQOL is comprised of a core component that measures health-related quality of life (KDQOL-36) in addition to 11 multi-item domains targeted at particular concerns of patients undergoing dialysis that measure kidney disease-specific quality of life. The KDQOL-36 is comprised of eight domains (physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health perceptions, emotional well-being, role limitations due to emotional problems, social functioning, and energy). We calculated and linearly converted SF-36 domain scores to a 0- to 100-point scale according to published guidelines, with higher scores reflecting better HRQOL (33,34). Physical HRQOL and mental HRQOL summary scores were standardized to the 1998 U.S. adult population and were thus converted to T-scores (mean=50 and a standard deviation [SD]=10) (31,35). Kidney disease-specific quality of life was assessed using 11 additional domains (symptoms, effects, burden, cognitive function, social interaction, sleep, social support, work status, dialysis staff encouragement, and patient satisfaction). We linearly converted kidney-disease specific domain scores to a 0- to 100-point scale in the same manner used for the SF-36 domains. A kidney disease-specific quality of life summary score was calculated from an average of the domain scores as has been previously reported (33,34,36).

Willingness to Perform Intradialytic Activity

Participants’ willingness to perform intradialytic physical exercise and cognitive tasks was surveyed using two close-ended questions: “Are you interested in exercising to improve your strength while on dialysis,” and “Are you interested in improving your memory through brain training while on dialysis?” Participants answered these questions verbally by responding “yes” or “no”.

Statistical Analysis

We tested whether there were differences in participant characteristics by intradialytic activity index using a Chi-squared test for categorical variables and the Student’s t-test for continuous variables. We identified correlates of higher intradialytic activity using ordered logistic regression, including age, sex, race, frailty, smoking status, CCI score, BMI, dialysis vintage, and education in a single model. Linear regression was used to examine the association between intradialytic activity index and physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL, adjusting for demographic and clinical factors including age, sex, BMI, dialysis vintage, race, and education. We used logistic regression to quantify the association between intradialytic activity index and intervention preferences. For all analyses, a p-value <0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using Stata 15/MP (College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Study Population of Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis

Among 431 participants undergoing hemodialysis, the mean age was 54 years (SD=13; range: 20–83), 35.3% were women, 53.6% were African American, 8.6% were current smokers, and 5.6% of participants attained less than a high school education. The mean dialysis vintage was 2.5 years [SD=3.4]. Outside of the dialysis clinic, 83.1% reported participating in at least one leisure time physical activity in the last two weeks; the most commonly reported activities were walking (59.2%), moderately strenuous household chores (54.8%), gardening (13.2%), and calisthenics/general exercise (13.2%).

Intradialytic Activity

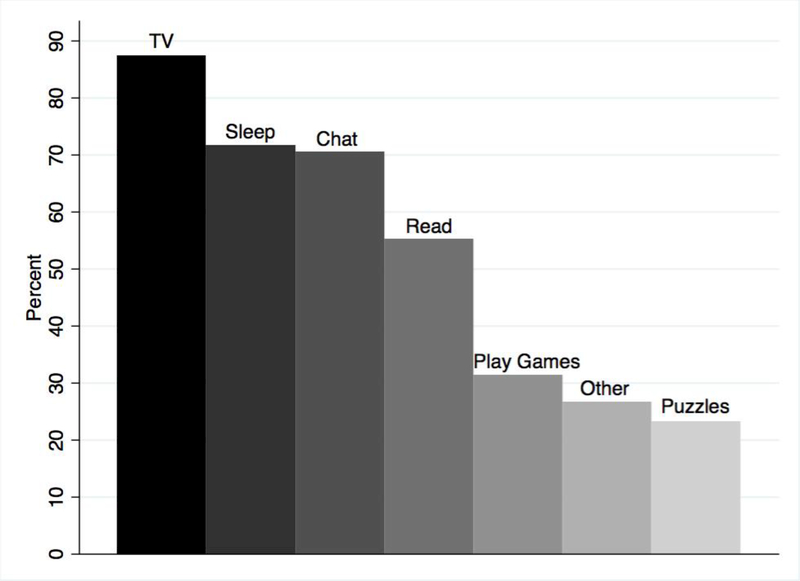

The most common intradialytic activities were watching TV (87.9%), sleeping (72.4%), and talking/chatting (70.5%) (Figure 1). A majority of participants reported performing both passive and active intradialytic activities (85.2%), while 1.4% of participants reported only active intradialytic activities and 13.5% reported only passive intradialytic activities. The intradialytic activity index ranged from 0 to 5 with 25.1% reporting 1 active intradialytic activity, 29.9% reporting 2 activities, 21.8% reporting 3 activities, 9.1% reporting 4 activities, and <1% reporting 5 activities; the median was 2 active intradialytic activities. The median active intradialytic activity index was 2 and did not vary by age (ages≥65 vs. age<65), comorbidity (CCI≥1 vs. CCI=0), or dialysis vintage (≥1 year or <1 year). There were 15 participants (3.4%) who reported eating while on hemodialysis. In addition to the list of possible intradialytic activities, other common responses that participants reported included listening to music/podcasts/educational lectures/audiobooks/news (9.0%), using social media/browsing internet (4.2%), working/studying (5.6%), and drawing/coloring/crafts (2.6%).

Figure 1:

Intradialytic Activities Reported among Adults Undergoing Hemodialysis (n=431). Participants undergoing hemodialysis reported what the normally do on dialysis. The most common activities were watching TV (87.9%), sleeping (72.4%), and talking/chatting (70.5%).

Correlates of Intradialytic Activity Level

Participants who were current smokers were more likely to report only passive intradialytic activities (15.5% vs. 7.5%; p=0.04) (Table 1). Participants who were female (aOR=1.85, 95%CI:1.28–2.66; p=0.001), nonfrail (aOR=1.70, 95%CI:1.06–2.70; p=0.03), and nonsmokers (aOR=2.61, 95%CI:1.39–4.90; p=0.003) were more likely to have a higher intradialytic activity index (Table 2). There were no significant differences in intradialytic activity index based on dialysis vintage, BMI, race, age, and Charlson comorbidity index.

Table 1.

Adults Undergoing Hemodialysis, Stratified by ‘Only Passive’ Intradialytic Activities and ‘Active or Both’ Intradialytic Activities (n=431).

| Intradialytic Activities |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Participants |

Passive (n=58) |

Active or Both (n=373) |

P-value | |

| Age (years), % | 0.75 | |||

| 18–34 | 10.2 | 13.8 | 9.7 | |

| 35–49 | 29.2 | 27.6 | 29.5 | |

| 50–64 | 38.1 | 34.5 | 38.6 | |

| ≥65 | 22.5 | 24.1 | 22.3 | |

| African American race, % | 53.6 | 50 | 54.2 | 0.56 |

| Hispanic ethnicity, % | 97.4 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 0.66 |

| Male sex, % | 64.7 | 67.2 | 64.3 | 0.68 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.2 [6.6] | 27.4 [5.7] | 28.3 [6.7] | 0.31 |

| Dialysis vintage (years), mean (SD) | 2.5 [3.4] | 2.5 [3.5] | 2.6 [2.8] | 0.81 |

| Highest level of education, % | 0.25 | |||

| Grade school | 5.6 | 5.2 | 5.6 | |

| High school | 30.2 | 37.9 | 29 | |

| Technical school | 12.1 | 3.5 | 13.4 | |

| College | 34.8 | 39.7 | 34.1 | |

| Graduate school | 16.9 | 13.8 | 17.4 | |

| Other | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | |

| Employed | 25.8 | 31 | 24.9 | 0.32 |

| Current smoker, % | 8.6 | 15.5 | 7.5 | 0.04 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 2.3 (2.3) | 2.3 (2.5) | 2.3 (2.3) | 0.98 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 12.1 | 8.6 | 12.6 | 0.38 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 5.8 | 3.5 | 6.2 | 0.41 |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 8.4 | 6.9 | 8.6 | 0.66 |

| Dementia | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Chronic lung disease | 3.7 | 6.9 | 3.2 | 0.17 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 6.5 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 0.9 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 2.1 | 0 | 2.5 | 0.23 |

| Diabetes | 49 | 46.6 | 49.3 | 0.69 |

| Diabetes with complications | 25.5 | 20.7 | 26.3 | 0.36 |

| Moderate/severe liver disease | 4.4 | 5.2 | 4.3 | 0.76 |

| Metastatic cancer | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.67 |

| Leukemia | 0.2 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.01 |

| Lymphoma | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.58 |

| Congestive heart failure | 16.6 | 27.8 | 14.9 | 0.05 |

| HIV | 5.3 | 6.9 | 5.1 | 0.57 |

| Frailty | 16 | 19 | 15.6 | 0.51 |

| Depressive symptoms | 25.8 | 27.6 | 25.5 | 0.73 |

Note: Active intradialytic activities include: read, play electronic games, puzzles, chat, other (physical or cognitive activity; passive intradialytic activities include: watch TV, sleep, other (non-physical or non-cognitive activity).

Table 2:

Correlates of Intradialytic Activity Level Among Adults Undergoing Hemodialysis (n=431).

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Older age (≥65 years) | 0.75 (0.50, 1.13) | 0.17 |

| Female sex | 1.85 (1.28, 2.66) | 0.001 |

| Black race | 1.09 (0.77, 1.55) | 0.63 |

| Less than a high school education | 0.78 (0.37, 1.64) | 0.5 |

| Nonfrail | 1.70 (1.06, 2.70) | 0.03 |

| Non-smoker | 2.61 (1.39, 4.90) | 0.003 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, for each 1- point increase in the index |

0.95 (0.88, 1.03) | 0.2 |

| Body mass index | ||

| Normal weight | Reference | |

| Overweight | 1.08 (0.69, 1.68) | 0.74 |

| Obese | 1.20 (0.80, 1.80) | 0.38 |

| Dialysis vintage (years) | ||

| <1 year | Reference | |

| 1–2 years | 0.83 (0.43, 1.60) | 0.57 |

| >2 years | 1.03 (0.73, 1.48) | 0.83 |

Note: Higher intradialytic activity levels as measured by this index reflect more activity during the dialysis session. All factors listed above were included in a single model.

Intradialytic Activity Level and HRQOL

The mean mental, physical, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL scores were 52.8 (SD=10.1), 41.6 (SD=9.9), and 74.0 (SD=15.7), respectively. Each 1-point increase in the intradialytic activity index was associated with a 0.83-point increase in mental HRQOL (+0.83 points; 95%CI: +0.04, +1.62; p=0.04) and 1.70-point increase in kidney disease-specific HRQOL (+1.70 points; 95%CI: +0.47, +2.93; p=0.007), after adjustment for demographic and clinical factors. However, the intradialytic activity index was not associated with physical HRQOL (+0.52 points; 95%CI: −0.27, +1.31; p=0.19) (Table 3). Results were consistent when we adjusted for categorical education level (highest level of education: grade school, high school, technical school, college, graduate school, or other) as a sensitivity analysis. Additionally, the association between intradialytic activity index and mental HRQOL (p for interaction=0.31), kidney disease-specific HRQOL (p for interaction=0.30), and physical HRQOL (p for interaction=0.28) did not differ between male and female participants.

Table 3:

Intradialytic Activity Level and Physical, Mental, and Kidney Disease-Specific Health-Related Quality of Life Among Adults Undergoing Hemodialysis (n=431).

| Difference in HRQOL score for each 1-point increase in activity index (95% CI) |

P- value | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical HRQOL | 0.52 (−0.27, 1.31) | 0.19 |

| Mental HRQOL | 0.83 (0.04, 1.62) | 0.04 |

| Domains: | ||

| Physical functioning | 1.97 (−0.02, 3.95) | 0.05 |

| Role limitations due to physical health problems | 0.73 (−2.28, 3.75) | 0.63 |

| Bodily pain | 1.28 (−0.95, 3.52) | 0.26 |

| General health | 1.27 (−0.60, 3.14) | 0.18 |

| Emotional well being | 1.33 (0.03, 2.62) | 0.04 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 1.56 (−1.14, 4.25) | 0.26 |

| Social functioning | 1.71 (−0.41, 3.83) | 0.11 |

| Energy | 2.97 (1.10, 4.84) | 0.002 |

| Kidney disease-specific HRQOL | 1.70 (0.47, 2.93) | 0.007 |

| Domains: | ||

| Symptoms | 1.32 (0.03, 2.61) | 0.046 |

| Effects | 2.18 (0.40, 3.96) | 0.02 |

| Burden | 2.76 (0.35, 5.17) | 0.03 |

| Cognitive function | 0.18 (−1.29, 1.66) | 0.81 |

| Social interaction | 1.01 (−0.38, 2.41) | 0.16 |

| Sleep | 2.66 (0.81, 4.51) | 0.005 |

| Social support | 1.79 (−0.07, 3.66) | 0.06 |

Note: Higher intradialytic activity levels as measured by this index reflect more activity during the dialysis session. Each measure of association was estimated using a separate model. All models are adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, dialysis vintage, and education.

At the HRQOL domain level, each 1-point increase in intradialytic activity index was associated with better scores in emotional well-being (+1.33 points; 95%CI: +0.03, + 2.62; p=0.04), energy (+2.97 points; 95%CI: 1.10, 4.84; p=0.002), symptoms of kidney disease (+1.32 points; 95%CI: +0.03, +2.61; p=0.046), effects of kidney disease on daily living (+2.18 points; 95%CI: +0.40, +3.96; p=0.02), burden of disease (+2.76 points; 95%CI: +0.35, +5.17; p=0.03), and sleep (+2.66 points; 95%CI: +0.81, +4.51; p=0.005), after adjustment for demographic and clinical factors (Table 3).

Intradialytic Activity Preferences

Among participants undergoing hemodialysis, 67.9% reported an interest in playing brain games during dialysis and 76.0% reported an interest in performing exercise during dialysis (Supplemental Table 1). A higher intradialytic index was associated with a 1.30-fold (95% CI: 1.08, 1.57; p=0.01) increased odds of being interested in playing brain games. A higher intradialytic index was also associated with a 1.25-fold (95% CI: 1.03, 1.52; p=0.03) increased odds of being interested in exercising during dialysis. Reported interest in playing games and performing exercise was similar among female, black, and older participants. Furthermore, younger (<65 years) participants undergoing hemodialysis were had a 3.15-fold (95% CI: 1.94, 5.13; p<0.001) increased odds of being interested in playing brain games but there was no association between age and interest in exercise.

DISCUSSION

Among this cohort of 431 adults undergoing hemodialysis, participants more commonly engaged in passive intradialytic activities such as watching television and sleeping compared to active tasks such as reading, completing puzzles, and playing electronic games. We found that participants with a higher intradialytic activity index had better mental HRQOL (+0.83 points per active intradialytic task) and kidney-disease specific HRQOL (+1.70 points per active intradialytic task), particularly within the domains of emotional well-being, energy, kidney disease symptomology, effects of disease on daily living, burden of disease, and sleep quality.

Participants with a higher intradialytic activity index were more likely to be female, nonsmokers, and nonfrail. Additionally, participants with a higher intradialytic activity index were more likely to be interested in exercising and performing cognitive tasks during dialysis. Of note, participants’ interest in these potentially beneficial activities did not differ by sex, or by race; however, younger (<65 years) participants were at a 3.15-fold increased odds of being interested in playing brain games compared to younger participants.

This was a large cohort study that characterized intradialytic activities among patients undergoing hemodialysis. Thus, our finding of a higher intradialytic activity index among females, nonsmokers, and nonfrail participants should be considered in the context of previous studies (37–39). For instance, smoking and frailty are also risk factors for lower leisure-time physical activity in this population (28,40). This fits with our conceptual model in which frail patients undergoing hemodialysis are particularly vulnerable to stressors induced by hemodialysis and thus, are less likely to be active during their session; we believe that frailty has both a direct impact on HRQOL (36,41) and indirectly impacts HRQOL through their inability to perform active intradialytic activities (ie full and partial mediation). Our finding of an association between frailty and lower intradialytic activity expands previously observed associations between frailty and increased risk of falls, hospitalization, and mortality, as well as declines in cognitive function and HRQOL in patients undergoing hemodialysis (4,5,7,27,36). As a marker of physiologic reserve, frailty captures an inability to efficiently recover from stressors (19). Our finding may further demonstrate that frail patients are less able to withstand the stressor involved with hemodialysis, which may be manifested in lower intradialytic activity.

Notably, we found that a higher intradialytic activity index was associated with better mental and kidney disease-specific HRQOL, which may reflect clinically significant findings, as each 1-point increase in mental HRQOL is associated with a two percent reduced relative risk of hospitalization (42,43). However, we observed no association in our study sample between intradialytic activity and physical HRQOL. It is likely that the cognitive nature of the intradialytic tasks reported by participants would have less impact on physical HRQOL. Currently, the Center for Medicare Services mandates dialysis facilities perform routine measures of quality of life (44); given this and our study findings, HRQOL may serve as a patient-centered outcome to determine the efficacy of dialysis facility interventions on intradialytic activity.

We found that participants were interested in performing additional activities during dialysis, namely physical exercise (76.0%) and cognitive tasks (67.9%). The willingness of patients to perform intradialytic physical exercise has thus far only been reported in smaller qualitative studies of 16–25 patients at individual dialysis centers (8,9) as well as a number of clinical trials of intradialytic physical activity (10–14). Our finding that participants with a higher intradialytic activity were more likely to report an interest in exercise and cognitive tasks may suggest that patients performing less activity during dialysis require additional support in order to increase activity level, particularly because lack of time on dialysis days is a commonly-reported barrier to exercise among hemodialysis patients (37). Furthermore, older patients were less likely to report an interest in exercise training and may need to have such interventions tailored to their interest. Additionally, while qualitative studies on intradialytic interventions have largely focused on exercise training (8,37), rather than cognitive training, these findings indicate wider patient-level interest in both physical and cognitive interventions. While our pilot study on intradialytic exercise and cognitive training suggests that these may be effective interventions to preserve cognitive function (45), we are starting a larger multi-center study of these interventions and plan to explore their impact on HRQOL (IMPCT trial).

This study has several important strengths, including the use of patient-reported measures of quality of life and intradialytic behaviors in combination with objective measures such as frailty. We used the KDQOL-SF instrument to assess quality of life, and this tool has both been rigorously validated among patients with ESRD (34) and has been established as an important predictor of health outcomes (2,42,43). The main limitation of our work is that this was a cross-sectional study, and this analysis does not establish a causal relationship between intradialytic activities and health-related quality of life. It is possible, though less plausible, that patients with poor HRQOL choose to participate in less active intradialytic activities but the temporality cannot be established in this study. Secondly, we assessed intradialytic activity by self-report and did not collect the duration of these activities during a dialysis session; however, participants were not made aware of which activities were considered active and which were considered passive. Thirdly, we did not have data on the type of vascular access or the amount of intradialytic weight loss. Finally, because the participants of this study were presenting for transplant evaluation, they may represent a population that is generally healthier, more educated, and functional compared to the general hemodialysis population (46). These participants may have different intradialytic activities from the hemodialysis population who are not referred for KT evaluation; the generalizability of these results should be confirmed in future studies. However, participants enrolled in this study were not enrolled from a single dialysis center which may increase the generalizability of our results.

In conclusion, we found that hemodialysis patients with greater intradialytic activities reported better mental and kidney disease-specific HRQOL and increased interest in participating in intradialytic interventions. Dialysis centers may consider offering patients with low levels of intradialytic activity additional support and opportunities to engage in beneficial intradialytic activities. Overall, hemodialysis patients may benefit from intradialytic interventions that offer a range of activity options that can be integrated into the existing dialysis routine and that provide patient-centered resources to address health-related quality of life.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the study participants for their commitment to this study.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK) grant numbers: R01DK114074 (PI: McAdams-DeMarco), K24DK101828 (PI: Segev), K23DK097184 (PI: Crews), and the National Institute on Aging (NIA) grant numbers: F32AG053025 (PI: Haugen), R01AG042504 (PI: Segev), K01AG043501 (PI: McAdams-DeMarco), and R01AG055781 (PI: McAdams-DeMarco). Mara A. McAdams-DeMarco was also supported by the Johns Hopkins University Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG021334). The funders above did not have a role in study design; collection, analyses, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liem YS, Bosch JL, Arends LR, Heijenbrok-Kal MH, Hunink MGM. Quality of life assessed with the medical outcomes study short form 36-item health survey of patients on renal replacement therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Value Heal. 2007;10(5):390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mapes DL, Lopes AA, Satayathum S, McCullough KP, Goodkin DA, Locatelli F. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization : The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study ( DOPPS ). Kidney Int. 2003;64(3):339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mapes DL, Bragg-Gresham JL, Bommer J, et al. Health-related quality of life in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(SUPPL. 2):54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAdams-Demarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. Frailty as a novel predictor of mortality and hospitalization in individuals of all ages undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):896–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bao Y, Dalrymple L, Chertow GM, Kaysen GA, Johansen KL. Frailty, dialysis initiation, and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1071–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster R, Walker S, Brar R, et al. Cognitive Impairment in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease: The Canadian Frailty Observation and Interventions Trial. Am J Nephrol. 2016:473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAdams-Demarco MA, Tan J, Salter ML, et al. Frailty and cognitive function in incident hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(12):2181–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson S, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Molzahn A. A Qualitative Study to Explore Patient and Staff Perceptions of Intradialytic Exercise. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:1024–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jhamb M, Mcnulty ML, Ingalsbe G, et al. Knowledge, barriers and facilitators of exercise in dialysis patients : a qualitative study of patients, staff and nephrologists. BMC Nephrol. 2016:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheng K, Zhang P, Chen L, Cheng J. Intradialytic Exercise in Hemodialysis Patients : A Systematic Review and. Am J Nephrol. 2014;4(40):478–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Konel J, Warsame F, et al. Intradialytic Cognitive and Exercise Training May Preserve Cognitive Function. Kidney Int Reports. 2017:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pupim LB, Flakoll PJ, Brouillette JR, Levenhagen DK, Hakim RM, Ikizler T a. Intradialytic parenteral nutrition improves protein and energy homeostasis in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(4):483–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young HML, March DS, Graham-Brown MPM, et al. Effects of intradialytic cycling exercise on exercise capacity, quality of life, physical function and cardiovascular measures in adult haemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;(April):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konstantinidou E, Koukouvou G, Kouidi E, Deligiannis A. Exercise training in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis: comparison of three rehabilitation programs. J Rehabil Medi. 2002;34(1):40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheema BSB, Smith BCF, Singh MAF. A rationale for intradialytic exercise training as standard clinical practice in ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(5):912–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Quan H, Ghali WA. Adapting the Charlson comorbidity index for use in patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(1 SUPPL. 2):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radloff LS. A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor HL, Jacobs DR, Schucker B, Knudsen J, Leon AS, Debacker G. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31(12):741–755. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–M157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Delgado C, et al. Factors associated with frailty and its trajectory among patients on hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(7):1100–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Tan J, et al. Frailty, Mycophenolate Reduction, and Graft Loss in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2015;99(4):805–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garonzik-Wang JM, Govindan P, Grinnan JW, et al. Frailty and delayed graft function in kidney transplant recipients. Arch Surg. 2012;147(2):190–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAdams‐DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. Frailty and Early Hospital Readmission After Kidney Transplantation. Am J Transpl. 2013;13(8):2091–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nastasi AJ, Mcadams-Demarco MA, Schrack J, et al. Pre-Kidney Transplant Lower Extremity Impairment and Post-Kidney Transplant Mortality. Am J Transplant. 2017:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAdams-Demarco MA, Law A, King E, et al. Frailty and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(1):149–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Isaacs K, Darko L, et al. Changes in frailty after kidney transplantation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(10):2152–2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McAdams-DeMarco A, Suresh S, Law A, et al. Frailty and falls among adult patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Delgado C, et al. Association between Body Composition and Frailty among Prevalent Hemodialysis Patients: A US Renal Data System Special Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(2):381–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haugen CE, Mountford A, Warsame F, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and sequelae of post-kidney transplant delirium. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Ying H, Thomas AG, Warsame F, Shaffer A. Frailty, Inflammatory Markers, and Waitlist Mortality Among Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease in a Prospective Cohort Study. Transplantation. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Carter WB. Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(5):329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hays Ron D., Kallich Joel D, Mapes Donna L, Coons Stephen Joel, WBC Naseem Amin and CK. Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form. Version 1.3. A Manual for Use and Scoring. Rand. 1997:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saban KL, Stroupe KT, Bryant FB, Reda DJ, Browning MM, Hynes DM. Comparison of health-related quality of life measures for chronic renal failure: Quality of well-being scale, short-form-6D, and the kidney disease quality of life instrument. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(8):1103–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saban KL, Bryant FB, Reda DJ, Stroupe KT, Hynes DM. Measurement invariance of the kidney disease and quality of life instrument (KDQOL-SF) across Veterans and non-Veterans. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware JE, Keller SD, Kosinski M. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User’s Manual. Boston, MA: Health Assessment Lab; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McAdams‐DeMarco MA, Ying H, Olorundare I, et al. Frailty and Health-Related Quality of Life in End Stage Renal Disease Patients of All Ages. J Frailty Aging. 2016;5(3):174–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delgado C, Johansen KL. Barriers to exercise participation among dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(3):1152–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blake C, Codd MB, Cassidy A, O’Meara YM. Physical function, employment and quality of life in endstage renal disease. J Nephrol. 2000;13(2):142–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Ng A V., et al. Physical activity levels in patients on hemodialysis and healthy sedentary controls. Kidney Int. 2000;57(6):2564–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tentori F, Elder SJ, Thumma J, et al. Physical exercise among participants in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study ( DOPPS ): correlates and associated outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(4):3050–3062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Olorundare IO, Ying H, et al. Frailty and Postkidney Transplant Health-Related Quality of Life. Transplantation. 2018;102(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowrie EG, Curtin RB, LePain N, Schatell D. Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36: A consistent and powerful predictor of morbidity and mortality in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(6):1286–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Block G, Humphreys MH. Association among SF36 quality of life measures and nutrition, hospitalization, and mortality in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(12):2797–2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schatell Dori; Witten B Measuring Dialysis Patients ‘ Health-Related Quality of Life with the Kidney Disease Quality of Life ( KDQOL-36 ™ ) Survey. KDQOL Complet. 2008;(608):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Konel J, Warsame F, et al. Intradialytic Cognitive and Exercise Training May Preserve Cognitive Function. Kidney Int Reports. 2018;3(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Balhara KS, Jaar BG, Segev DL. Disparities in provision of transplant information affect access to kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(2):351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.