Abstract

This paper investigates how social support differentially benefits self-rated health among men and women hospitalized with heart disease. Using cross-sectional data about patients admitted to a university hospital, we examine the extent to which gender moderates effects for the frequency of contact with family, friends, and neighbors on health, and whether these effects differ between those with new vs. established diagnoses. We find that gender differentiates the effect of non-marital family contact on health but only when heart disease is newly diagnosed. When newly diagnosed, more frequent contact from family is associated with better self-rated health for women but not men. Men and women with pre-existing diagnoses benefit equally from more frequent contact with family.

There is an established relationship between social support and health: those with access to family and friends are healthier than those without these social ties (Uchino, Cacioppo, and Kiecolt-Glaser 1996; Reblin and Uchino 2008). Gender also differentiates health outcomes, albeit in paradoxical ways. Women have higher morbidity rates, with more chronic conditions and disability, but they also live longer than men, who experience more life-threatening acute illnesses and die younger (Bird and Rieker 2008). Women are also more likely than men to be depressed (Gorman 2006). Yet, although clear gender patterns emerge from studies addressing the marital components of social support, findings about non-marital dimensions of social support are less clear, as we show below.

In this paper, we consider “the stage of disease potentially impacted by social support” (Uchino 2006: 382) by examining whether and how disease onset matters in the process by which gender differentiates the effects of non-marital support on self-reported health. We draw on prior research about how social support and its relationship to health varies by gender, and test hypotheses about gender-moderating effects of support and how they differ by timing of diagnosis. We focus on the consequences of gender differences for the health of heart disease patients to remedy existing knowledge about cardiovascular disease, which until recently has focused on men (Lee et al. 2001). To do this, we analyze data collected from heart disease patients admitted to a university hospital. We also rely on medical records data from these patients to assess how support operates at different developmental stages of heart disease: i.e., at onset, or when first diagnosed, compared to having a pre-existing diagnosis. Overall, gender differentiates the effects of non-marital family support only when heart disease is newly diagnosed, suggesting that the health benefits of non-marital family support vary as the disease process begins and progresses.

BACKGROUND

Literature Review

Social support takes various forms. It is instrumental, e.g., tangible and/or financial assistance (House 1981); emotional, e.g., involving love, sympathy, and/or understanding from others (Thoits 1995); or informational, e.g., assistance in making decisions and giving feedback (Cohen and Willis 1985). Some conceptualizations differentiate between structural components, such as participating in a social network, and functional dimensions, including positive or negative interactions with others (Cohen and Wills 1985; Reblin and Uchino 2008).

Intimacy of support and/or perceived responsiveness are also important, especially given a serious health condition. Close family and friends may offer more intimate and useful social support, whereas support from casual friends and acquaintances may be less beneficial (Antonucci 1985; Li et al. 2014). Prior studies also report that family social support improves cardiovascular regulation (Dressler 1980; Spitzer et al. 1992; Uchino, Cacioppo and Kiecolt-Glaser 1996). However, Bolger et al. (1996) show that although close network members are called on after a serious diagnosis, it may also lead them to withdraw as they cope with the stressful situation.

In addition to receiving support, studies consider the benefits and costs of giving support (Thoits 1995). Ishikawa et al. (2014) and Thomas (2010) find that providing support improved health behaviors and well-being more than receiving it. Brown et al. (2003) reveal lower mortality risks for those providing instrumental support to friends and relatives and emotional support to spouses. However, Thoits (1995) notes there are costs to giving support and/or caring for others (see also Aneshensel, Pearlin, and Schuler 1993; Wakabayashi and Donato 2006).

Uchino et al. (2012) emphasize the context of support, consideration of more specific health states, and a life-course perspective. In one study, Thoits (2011) distinguishes between primary and secondary groups. The former are persons with close informal ties, and latter represent those with more formal, less personal ties who use discretion to enter and exit support groups. Primary group members are more effective giving emotional support, but secondary groups are more effective giving informational assistance. Other studies examine how the social support-health relationship varies across the life cycle (Umberson and Montez 2010; Umberson, Crosnoe, and Reczek 2010). Without many social ties, stressful relationships create cumulative life course disadvantages (Berkman and Syme 1979; Luo et al. 2012).

Gender, Social Support and Health

For decades, researchers have linked social support to morbidity and mortality (Wallston et al. 1983; Berkman et al. 2000; Cohen 1988; House, Landis, and Umberson 1988; Seeman 1996; Uchino 2004; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, and Layton 2010; Pinquart and Duberstein 2010). Less support, fewer ties, and weak social integration are related to higher mortality, especially from cardiovascular disease (Berkman, Leo-Summers, and Horwitz 1992; Frasure-Smith et al. 2000; Orth-Gomér, Rosengren, and Wilhelmsen 1993; Williams et al. 1992). Yet prior studies are inconsistent about gender differences in social support.

Because it is inextricably linked to socialization, gender underlies the emergence and perpetuation of social networks, leading to differences in receipt of social support (Shumaker and Hill 1991).1 Men’s networks are less intimate and intensive because they often view spouses as primary sources of support (Belle 1987). Women identify friends and family, including spouses, as intimate sources of support (Powers and Bultena 1976). Not only are women’s networks more extensive than men’s, women are more involved in the lives of others (Wethington, McLeod, and Kessler 1987). Compared to men, married women had larger networks and received support from multiple sources, and the quality and quantity of support had larger health benefits for women (Antonucci and Akiyama 1987).

Although marriage is a salient social form of social support (Waite and Gallagher 2000; Umberson and Montez 2010; Liu 2012), marital disruption – in the form of being divorced or widowed – worsens health (Hughes and Waite 2009). In addition, there are substantial gender differences. Studies suggest that marriage is positive and lowers the mortality risks of men not women (House et al. 1982; Shumaker and Hill 1991). Men benefit through positive lifestyle and health behaviors learned with marriage and via lower costs experienced from spousal caregiving, childrearing, caring for aging parents, and balancing work/family demands (Waite 1995). Therefore, married men’s health is better than their spouses because men benefit from spouses’ efforts to improve health (Umberson 1992).

In contrast, women may experience more everyday strain in marriage (Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton 2001) because they are more troubled than men by problems in close relationships (Davis and Greenstein 2009). One consequence is greater physiological effects that undermine the health benefits of marriage for women.2 Zhang and Hayward (2006) found that, although middle-aged men and women with a marital loss had higher cardiovascular disease prevalence at baseline than those without such a loss, in late midlife women who did not remarry had higher risks relative to continuously married women. Liu and Waite (2014) found that poor marital quality and marital loss were more strongly linked to women’s cardiovascular risks than men’s, and Cable et al. (2013) reported being married improved men’s psychological well-being at age 50 but not women’s.

Gender differences also exist in non-marital forms of social support. Meaningful contact with friends and family, such as how much respondents felt spouses, family, and friends understood their feelings and cared about them, is more positive for women than men (Walen and Lachman 2000). Lyyra and Heikkinen (2006) reported that perceptions of low emotional support predicted higher mortality among elderly women (but not men), after controlling for other attributes.2

In an extensive review, Uchino et al. (1996) found that social support improved cardiovascular regulation in both men and women, However, of the twenty studies including men and women, only eight reported gender effects. Shye et al. (1995) found evidence of gender differences in the effects of network size on mortality: men’s mortality risks benefitted more from smaller networks than women’s. Gallicchio, Hoffman, and Helzlsouer (2007) reported that, despite higher mortality and lower life expectancy, men reported higher quality of life although social support improved both sexes’ health-related quality of life.

Therefore, our first hypothesis is below:

H1: Frequency of contact with family, friends, and neighbors will be positively associated with women’s health ratings more so than men’s.

Why Disease Timing Matters

Following Uchino’s (2006: 382) call for “more data on the stage of disease potentially impacted by social support,” we draw on studies that consider the relationship between social support, stress, and physical health.3 Stressful events may produce different responses for men and women, and stress from illness diagnosis may shift resources embedded in social networks.

There are many ways that people respond to and/or cope with stress. As Taylor et al. (2000: 411) described, Cannon’s (1932) fight-or-flight response was considered “the prototypic human response to stress.” Behaviorally, the fight-or-flight metaphor describes an acute stress response of males who, because they perceive survival as being threatened, harmed, or attacked, reacts by fighting or fleeing the stressor.4

Taylor et al. (2000) argue that women’s stress response may take the form of fight or flight, but it may also take another form: tend-and-befriend. Faced with stressful conditions, women respond in complex ways, caring for offspring, joining groups to reduce susceptibility, and developing social ties – especially with other women – to exchange resources and share responsibilities. Thus, gender differentiates stress responses; women’s are maternal and affiliative and men’s are fight-flight. Although the physiological neuroendocrine stress response is the same for both, women’s pregnancy and maternal demands translate into a different adaptation process whereby they protect offspring now and in the future. This is consistent with studies documenting that, under stressful conditions, women are more likely to seek out sources of social support (Wethington, McLeod, and Kessler 1987) and they are no more psychologically reactive than men (Umberson et al.1996). Moreover, men form larger groups (Baumeister and Sommer 1997) into which defined hierarchies and tasks are embedded but without the socioemotional bonding in women’s groups (Cross and Madson 1997).

If Taylor et al. (2000) are correct in suggesting women’s stress responses are more affiliative than men’s, then women will adapt to a stressful event by relying on support from groups of people rather than a few individuals. Therefore, at the onset of disease trajectories, when diseases are first diagnosed, women will have more social support resources to activate and they will be more beneficial than men’s. But what happens to social support and its gender moderating effects as a disease progresses?

Perry and Pescosolido (2012: 139) suggest that demands for social support are dynamic as illness trajectories shift because illness contains “disruptive episodes that are characterized by interdependent patterns and pathways of decisions, social interactions, and experiences.” Comparing the social networks of mental health patients across three years to a representative sample of persons with no self-reported mental illness, they report that network size declined among users of mental health services after illness onset but it increased among those without mental illness. As people progressed through treatment, previously supportive persons dropped out of patients’ networks, increasing support by members in smaller, newly rearranged, networks. Thus, “social network dynamics reflect changing needs and resources”: mentally ill patients learned to manage their illness but with less support (Perry and Pescosolido 2012: 134). People leave networks for many reasons: either the situation is too stressful or the illness stage demands a different type or amount of social support than what he/she usually provides.

Following Perry and Pescosolido (2012), we consider illness development as a turning point. A new medical diagnosis is disruptive and requires different social support than a chronic illness; each episode evokes distinct support patterns that may or may not reflect established gendered differences. Being admitted to a hospital with a new heart disease diagnosis is the first stage in a stressful set of episodes that requires different amounts and types of social support than being admitted with a pre-existing diagnosis. Compared to chronic disease progression, disease onset is a crisis moment when social support mobilizes in size and functionality (Carpentier and Ducharme 2005). Because they traditionally affiliate in groups that offer socio-emotional support, women are more likely to reap support benefits at disease onset than men. However, throughout disease progression, gender is less likely to moderate support effects because these resources experience turnover and become smaller in size and more specific to patients’ needs.5

Therefore, we expect that:

H2: Gender moderates the effects of social support when an illness is first diagnosed. Women will be more likely than men to benefit from more frequent contact with family, friends, and neighbors at the early stage of disease progression.

H3: At later stages of disease progression, gender will not differentiate effects for social support. Although more contact with family, friends, and neighbors may be beneficial, men and women will benefit equally.

Data and Methods

We use data from the Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS), a prospective longitudinal study of 3,000 patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndrome or congestive heart failure (Meyers et al. 2014). Patients were enrolled and data collected between 2011 and 2016. To enroll respondents, trained assistants and study physicians reviewed daily hospital records for patients admitted to the hospital for either acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or exacerbation of congestive heart failure (CHF). The Centers for Disease Control define ACS as a diagnosis that includes patients that have had a heart attack or unstable angina. CHF refers to patients that have fluid buildup in the lungs, liver, gastrointestinal tract, and/or arms and legs. Of the two, CHF portends a worse prognosis because it is chronic and signals a weak heart muscle that cannot pump enough blood. ACS is more amenable to acute treatments such as angioplasty.

After reviewing hospital records, research staff then approached potential study participants to verify eligibility. Principal exclusion criteria were being too ill to complete the in-hospital interview, severe cognitive impairment, lack of reliable follow-up contact information, inability to communicate in English, unstable psychiatric illness, and in hospice care. Of those eligible, approximately 80 percent consented and enrolled. After obtaining written informed consent, interviewers gathered baseline survey data during hospitalization using tablet computers at patients’ bedsides.

VICS data include information about demographic, cognitive, psychological, behavioral, and functional health, and social support. Trained nurses also recorded data from medical records, including whether diagnosis at the time of hospitalization was new or pre-existing. For ACS respondents, the pre-existing condition was a history of coronary artery disease (a chronic narrowing and limitation of blood flow in the arteries); for those admitted with an exacerbation of CHF, the pre-existing condition was chronic diagnosis of CHF.

This analysis uses baseline cross-sectional data from respondents with ACS or CHF and for whom medical record data were available. From the completed 3,000 sample, we removed those diagnosed with both ACS and CHF (n=197) because we could not assess, at the time of hospitalization, whether both conditions were diagnosed at the same time, or if one was new and the other pre-existing. We also removed 158 cases for whom we had missing observations on some variables, including income.6 The final analytic sample is 2,645 respondents.

The dependent variable measures self-rated health status derived from questions in the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) (Hays et al. 2009). Cella et al. (2010) found that all PROMIS items have both strong reliability and construct validity. To calculate the dependent variable, we summed responses to three questions about self-rated general, physical and mental, health. Responses for each ranged from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent); after creating the summary index, responses ranged from 3 (low self-rated health) to 15 (high self-rated health).7

Our key interest is in three variables that measure the presence of potential and actual sources of non-marital support received from family, friends, and neighbors. (VICS does not have information about giving support.) These items, which proxy received network social support, derive from the Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) study, and assess frequency of contact with friends, family, and neighbors (Rossi 2004). Frequency of contact with family (or friends) includes visits, phone calls, letters and emails with family (or friends) not living with respondents; these two variables range from 1 (never) to 8 (several times a day). Frequency of neighbor contact is frequency of any contact with neighbors, ranging from 1 (never) to 8 (several times a day). For these three measures, higher scores indicate more contact. The two other variables of interest are onset of disease and gender. From respondents’ medical records, we include a variable indicating whether a respondent’s diagnosis at hospitalization is new (=1) or pre-existing (=0). Gender is coded as 1=female, 0=male.

We also control for other variables that capture dimensions related to social support. From the Health and Retirement Study, we use two items that are counts of relatives and friends with whom respondents have close relationships (Juster and Suzman 1995). In addition, we use the ENRICHD Social Support Instrument as a valid indicator of perceived social support for coronary artery patients (Vaglio et al. 2004).8

We operationalize other social determinants, such as socioeconomic position and race, which influence cardiovascular disease (Havranek et al. 2015). We include human capital characteristics (education and age); employment status; and annual household income. We measure age and education in continuous years. Race and employment status are dichotomous variables where 1=nonwhite and 0=white,9 and 1=employed and 0=unemployed, homemaker, retired, student, or disabled. We also assess the independent effect of being married or living with a partner (=1) vs. being single, separated, divorced, or widowed (=0). Last year’s household income is in five continuous categories, ranging from 1=less than $20,000 to 5=$100,000 or more. Finally, we include a dummy variable for type of diagnosis (1=ACS and 0=CHF).

Analytic Plan

We begin with descriptive statistics, emphasizing differences by gender and for those with pre-existing and new diagnoses. The multivariate models examine effects of gender, frequency of contact with family, friends, and neighbors, and onset of diagnosis, on self-rated health net of other variables. To assess the first hypothesis (that gender differentiates the effects for non-marital support), we examine interaction coefficients between gender and frequency of contacts with family, friends, and neighbors for the total sample.10 We then investigate differences between pre-existing and newly diagnosed respondents and allow for the possibility that both the effects of family, friends, and neighbor contact and the moderating effect of gender vary by timing of diagnosis. Thus, evidence related to the second and third hypotheses derives from interactions that examine whether and how gender moderates effects for frequency of contacts with family, friends, and neighbors for respondents whose disease is newly diagnosed and those with pre-existing diagnoses. To illustrate the findings, we visually describe significant gender differences.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all variables. The bottom row shows distributions of men and women across the three samples. Men comprise more than half of these three groups. Men’s representation (in the total sample and two sub-samples) is consistent with national data that show women’s representation in various forms of cardiovascular disease is lower than men’s (Mosca et al. 2011). Knowledge about cardiovascular disease and its treatment is largely based on data about men (Sinha and Tremmel 2007), a point we return to in the discussion.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for All Variables by History of Diagnosis and Gender.

| Total Sample | Preexisting Diagnosis | New Diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Dependent Variable | ||||||

| Self-Rated Health | 8.53 (2.59) | 7.97 (2.59)*** | 8.12 (2.46) | 7.48 (2.45)*** | 9.06 (2.67) | 8.66 (2.64)* |

| Key Independent Variables | ||||||

| % New Diagnosis (ref=preexisting) | 42.78 | 40.99 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Extent of Contact with Network | ||||||

| Contact with Family | 6.02 (1.69) | 6.60 (1.62)*** | 6.04 (1.71) | 6.65 (1.60)*** | 5.99 (1.68) | 6.53 (1.65)*** |

| Contact with Friends | 5.74 (1.98) | 5.87 (1.97) | 5.69 (2.02) | 5.81 (1.98) | 5.80 (1.92) | 5.95 (1.95) |

| Contact with Neighbors | 5.28 (2.18) | 5.15 (2.29) | 5.33 (2.15) | 5.19 (2.33) | 5.22 (2.23) | 5.09 (2.25) |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Number of Close Relatives | 4.60 (3.10) | 4.84 (3.06)* | 4.53 (3.12) | 4.80 (3.12) | 4.68 (3.04) | 4.91 (2.97) |

| Number of Close Friends | 4.35 (3.26) | 3.82 (2.88)*** | 4.37 (3.29) | 3.69 (2.83)*** | 4.32 (3.21) | 4.00 (2.96) |

| Perceived Social Support | 25.99 (4.75) | 25.78 (4.53) | 26.00 (4.86) | 25.57 (4.68) | 25.98 (4.61) | 26.08 (4.30) |

| Age (years) | 60.04 (11.78) | 60.55 (13.17) | 60.09 (11.93) | 60.86 (13.09) | 59.97 (11.60) | 60.1 (13.30) |

| % Nonwhite (ref=white) | 12.99 | 18.86*** | 13.84 | 21.94*** | 11.85 | 14.42*** |

| % Married/Partnered (ref=unmarried) | 68.94 | 49.06*** | 70.32 | 49.17*** | 67.11 | 50.34*** |

| Education (years) | 13.91 (2.99) | 13.25 (2.65)*** | 13.99 (3.10) | 13.10 (2.74)*** | 13.80 (2.83) | 13.47 (2.53)* |

| Household Income | ||||||

| % < $20,000 | 16.73 | 28.52*** | 18.05 | 31.96*** | 14.96 | 23.57*** |

| % $20,000 to < $50,000 | 38.33 | 46.34*** | 37.43 | 46.74*** | 39.56 | 45.77* |

| % $50,000 to < $75,000 | 15.78 | 12.01** | 15.95 | 11.61* | 15.56 | 12.59 |

| % $75,000 to < $100,000 | 11.60 | 6.00*** | 11.63 | 4.61*** | 11.56 | 8.00 |

| % $100,000 or more | 17.55 | 7.13*** | 16.94 | 5.09*** | 18.37 | 10.07*** |

| % Employed (ref=unemployed) | 41.25 | 25.70*** | 35.22 | 20.92*** | 49.33 | 33.64*** |

| % ACS (ref=CHF) | 70.27 | 63.04*** | 56.58 | 49.60** | 88.59 | 82.38** |

| N | 1579 | 1066 | 903 | 629 | 676 | 437 |

Note: Means/percentages presented. Standard deviations in parentheses. Asterisks denote significant differences between men and women,

p<.05

p<.01, and

p<.001 (two-tailed tests).

ACS=acute coronary syndrome, CHF=congestive heart failure

The first two columns refer to gender differences for the total sample. Results suggest that men and women differ in self-reported health: men’s rankings are significantly higher than women’s. Women also report significantly more family contact than men. Although women also report slightly more frequent contact with friends, and men more contact with neighbors, these differences are not significant. In addition, women report having significantly more close relatives and men report significantly more close friends, but perceived social support does not vary by gender. Men are less likely to be nonwhite but more likely to be married, with more education and higher household income, and they are more likely to be employed than women. Men are also more likely to have been hospitalized for ACS.

The second set of columns in Table 1 presents gender differences among respondents with pre-existing diagnoses, and the third set compares men and women with new diagnoses. Some gender differences in the total sample appear in these sub-samples. For example, among those with pre-existing or new diagnoses, men report significantly better health than women. These men also report significantly less contact with family, but no other gender differences exist in frequency of contact with friends or neighbors. Moreover, only men with a pre-existing diagnosis report significantly more close friends than women, and there are no gender differences in perceived social support. Once again men were less likely to be non-white, but more likely than comparable women to be married/partnered, with more education and household income, and more likely to be employed. We also see a gender difference in diagnosis type. Among those with pre-existing diagnoses, 56.6 percent of men had ACS compared to 49.6 percent of women.

As expected, those receiving a new diagnosis reported better health than those with a pre-existing diagnosis and men reported better health than women. Similar to those with pre-existing diagnoses, women with new diagnoses reported greater frequency of contacts with family than men. Yet, in contrast to those with pre-existing diagnoses, among those newly diagnosed there was no gender difference in the number of close friends. Men with new diagnoses were more likely to be married/partnered, with slightly higher levels of education and household income, and they were more likely to be employed, than comparable women. Again, a gender difference in type of diagnosis appears: 88.6 percent of newly diagnosed men had ACS compared to 82.4 percent of comparable women.

Multivariate Models: Effects of Gender, Social Support, and Timing of Diagnosis

Table 2 presents multivariate models predicting self-rated health for the total sample. Model 1 summarizes main effects, and Models 2-4 present interactions between gender and frequency of contacts with family, friends and neighbors. The findings offer some evidence in support of our first hypothesis, i.e., that frequency of contact with others – as a proxy of social support – is positively associated with women’s health more so than men’s.

Table 2.

Self-Rated Health for the Total Sample Regressed on Extent of Contact with Network (N=2,645)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Key Independent Variables | ||||||||

| Female (ref=male) | −.207* | .096 | −.224* | .096 | −.209* | .096 | −.207* | .096 |

| New Diagnosis (ref=preexisting) | .679*** | .096 | .682*** | .096 | .679*** | .096 | .679*** | .096 |

| Extent of Contact with Network | ||||||||

| Contact with Family | .005 | .029 | −.034 | .036 | .005 | .029 | .005 | .029 |

| Contact with Friends | .075** | .026 | .076** | .026 | .094** | .031 | .075** | .026 |

| Contact with Neighbors | .034 | .021 | .034 | .021 | .033 | .021 | .037 | .027 |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Female × Contact with Family | ---- | ---- | .103* | .050 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Female × Contact with Friends | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | −.047 | .046 | ---- | ---- |

| Female × Contact with Neighbors | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | −.008 | .041 |

| Control Variables | ||||||||

| Number of Close Relatives | .023 | .016 | .023 | .016 | .023 | .016 | .023 | .016 |

| Number of Close Friends | .053** | .017 | .054** | .017 | .053** | .017 | .053** | .017 |

| Perceived Social Support | .063*** | .011 | .063*** | .011 | .063*** | .011 | .063*** | .011 |

| Age (years) | .033*** | .004 | .033*** | .004 | .033*** | .004 | .033*** | .004 |

| Age Squared | .001*** | .000 | .001*** | .000 | .001*** | .000 | .001*** | .000 |

| Nonwhite (ref=white) | .271* | .130 | .265* | .130 | .274* | .130 | .270* | .130 |

| Married/Partnered (ref=unmarried) | −.106 | .108 | −.101 | .108 | −.107 | .107 | −.107 | .107 |

| Education (years) | .107*** | .017 | .107*** | .017 | .108*** | .017 | .107*** | .017 |

| Household Income | .140*** | .026 | .140*** | .026 | .140*** | .026 | .139*** | .026 |

| Employed (ref=unemployed) | 1.049*** | .111 | 1.055*** | .111 | 1.048*** | .111 | 1.051*** | .111 |

| ACS (ref=CHF) | .515*** | .106 | .508*** | .106 | .517*** | .106 | .516*** | .106 |

| Constant | .385 | .430 | .610 | .446 | .274 | .446 | .366 | .440 |

| R-Square | .243 | .244 | .244 | .243 | ||||

Note:

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001 (two-tailed tests).

ACS=acute coronary syndrome, CHF=congestive heart failure

Model 1 reveals a significant negative effect for being female: women report significantly worse health than men. Also, the coefficient for timing of diagnosis is robust and positive. Compared to those with pre-existing diagnoses, those with new diagnoses report significantly better self-rated health. With respect to frequency of contacts with family, friends, and neighbors, Model 1 shows that only frequency of contact with friends is uniquely associated with self-rated health. Among the covariates, the number of close friends and perceived social support are positively associated with self-rated health. Coefficients for age and age squared suggest a nonlinear relationship. Each additional year of age is positively associated with an increase in self-rated health but this effect is smaller in later, than in earlier, years. There is a significant race effect, with non-whites reporting better health. Interestingly, in the presence of the other variables there is no effect for being married/partnered. However, socio-economic status is consistently and positively associated with self-rated health. It improves with more education and more income, and it is significantly higher among those who are employed. In addition, relative to those with congestive heart failure, ACS respondents reported better health.

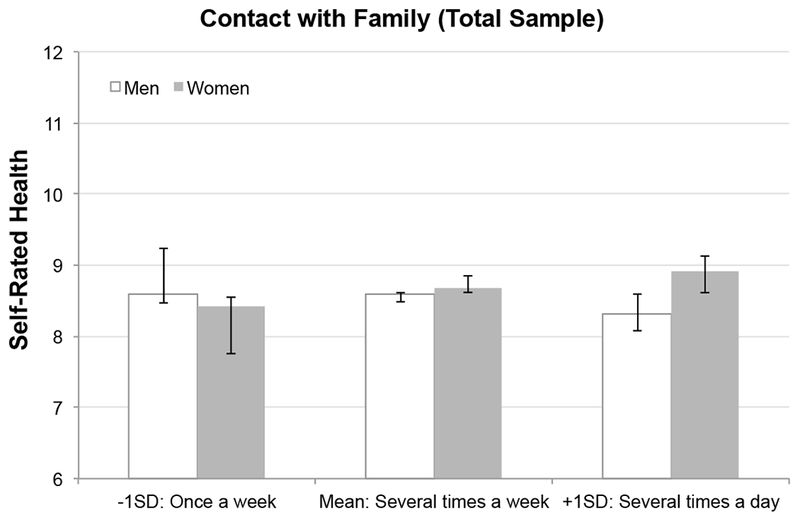

Model 2 reveals a significant interaction between being female and frequency of family contact. More contact with family is associated with greater improvements in women’s, than in men’s, health. Men, on the other hand, report a slight decrease in health as family contact increases. Although Models 3 and 4 examine similar interactions between being female and frequency of contact with friends and neighbors, the coefficients for the interaction terms are not significant. Together, the findings offer partial evidence for the first hypothesis: gender significantly interacts with frequency of non-marital family contacts to affect self-rated health.

To visualize this finding, we graphically display the predicted values of self-rated health using coefficients from Model 2. Figure 1 shows that, among women, the effect of having more family contact is positive. At low levels of contact with family, mens’ and womens’ reports of self-rated health are comparable and not statistically different. However, as frequency of family contact increases, at and exceeding its mean, e.g. several times a week, women’s self-rated health significantly improves beyond that for men. However, although this is some evidence in support of the first hypothesis, the other models do not reveal significant interaction coefficients.

Figure 1.

Significant Gender Differences in the Effect of Contact with Family on Self-Rated Health, Total Sample (N=2,645)

Table 3 reports selected coefficients from models estimating separate equations for respondents by when they were diagnosed. We begin with results for respondents with pre-existing diagnoses. We show only Model 1, which presents the main effects, because all three interaction terms between gender and frequency of contact from family, friends, and neighbors were not significant for those with pre-existing diagnoses. Appendix A presents models with coefficients for non-significant interactions.

Table 3.

Self-Rated Health Regressed on Extent of Contact with Network by History of Diagnosis (Selected Models)

| Preexisting Diagnosis | New Diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Key Independent Variables | ||||||

| Female (ref=male) | −.294** | .122 | −.144 | .154 | −.162 | .154 |

| Extent of Contact with Network | ||||||

| Contact with Family | .021 | .037 | −.002 | .047 | −.070 | .059 |

| Contact with Friends | .101** | .032 | .037 | .043 | .037 | .043 |

| Contact with Neighbors | .058* | .026 | .001 | .034 | .002 | .034 |

| Significant Interaction | ||||||

| Female × Contact with Family | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | .178* | .089 |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Number of Close Relatives | .013 | .020 | .030 | .027 | .030 | .027 |

| Number of Close Friends | .053* | .021 | .056* | .027 | .056* | .027 |

| Perceived Social Support | .053*** | .013 | .077*** | .017 | .076*** | .017 |

| Age (years) | .033*** | .005 | .036*** | .007 | .037*** | .007 |

| Age Squared | .001*** | .000 | .001*** | .000 | .001*** | .000 |

| Nonwhite (ref=white) | .233 | .158 | .347 | .223 | .332 | .223 |

| Married/Partnered (ref=unmarried) | −.203 | .139 | .007 | .171 | .002 | .171 |

| Education (years) | .080*** | .021 | .151*** | .030 | .152*** | .030 |

| Household Income | .129*** | .033 | .152*** | .042 | .151*** | .042 |

| Employed (ref=unemployed) | 1.088*** | .144 | 1.018*** | .175 | 1.046*** | .175 |

| ACS (ref=CHF) | .672*** | .119 | .060 | .220 | .058 | .220 |

| Constant | .730 | .523 | .593 | .746 | .930 | .764 |

| R-Square | .237 | .197 | .200 | |||

| N | 1,532 | 1,113 | 1,113 | |||

Note:

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 (two-tailed tests).

ACS=acute coronary syndrome, CHF=congestive heart failure

Appendix A.

Wording and Operationalization of Measures for Self-Rated Health and Extent of Contact with Family, Friends, and Neighbors

| DependentVariable | |

|---|---|

| Self-Rated Health | Constructed using the sum of three items from the NIH Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health Scale: (1) In general, would you say your health is…; (2) In general, how would you rate your physical health (which includes physical illness and injury)?; (3) In general, how would you rate your mental health, including your mood and your ability to think? Responses for each item ranged from 1=Poor to 5=Excellent. Responses for the summed measure range from 3 to 15, with higher scores indicating better self-rated health. |

| Key Independent Variables | |

| Extent of Contact with Family, Friends, and Neighbors | |

| Contact with Family | Respondent was asked: “How often are you in contact with any members of your family who do not live with you, such as your brothers, sisters, parents, or adult children -- including visits, phone calls, letters, or electronic mail messages?” Responses ranged from 1=Several times a day to 8=Never or hardly ever, but were reverse coded so that higher scores indicate more contact. |

| Contact with Friends | Respondent was asked: “How often are you in contact with any of your friends -- including visits, phone calls, letters, or electronic mail messages?” Responses ranged from 1=Several times a day to 8=Never or hardly ever, but were reverse coded so that higher scores indicate more contact. |

| Contact with Neighbors | Respondent was asked: “How often do you have any contact -- even something as simple as saying “hello” -- with any of your neighbors?” Responses ranged from 1=Several times a day to 8=Never or hardly ever, but were reverse coded so that higher scores indicate more contact. |

Coefficients from Model 1 show that women with pre-existing diagnoses report significantly lower self-rated health than men. Greater frequency of contact with friends and neighbors are associated with better self-rated health, and so too is having more close friends and perceived social support, net of other factors. All socioeconomic characteristics are also positively associated, but neither race nor being married/partnered matter for those with pre-existing diagnoses.

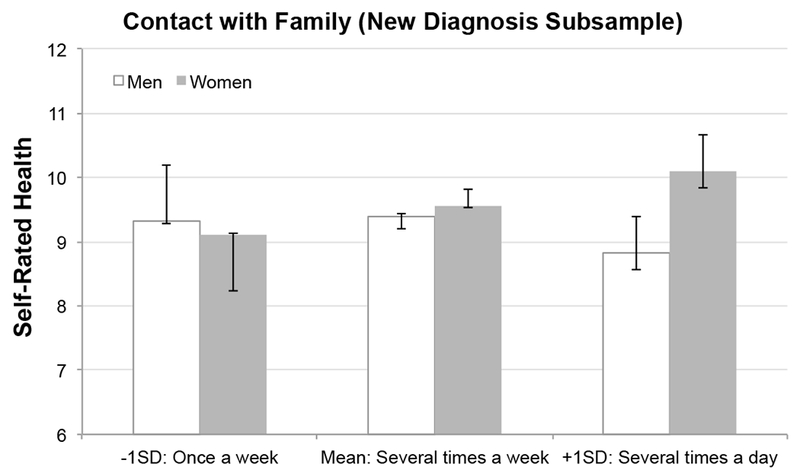

Model 2 in Table 3 presents the main effects for the newly diagnosed subsample, and Model 3 presents model coefficients that contain the significant gender-by-frequency-of-family-contact interaction.11 In contrast to those with pre-existing diagnoses, we find that gender moderates the effect for frequency of family contact. Specifically, being female potentiates the effect for greater contact with non-marital family members not living with respondents. Once again, to visualize these results, we calculated predicted values of self-rated health. Figure 2 illustrates gender differences by frequency of contact with family for those with new diagnoses (derived from Model 3 in Table 3). We see that the effect of frequency of family contact for women is strong and positive. As frequency of contact with family approaches its mean, e.g. several times a week, women’s self-rated health slightly surpasses the health of men (see Figure 2). Above the mean, with daily or more contact with family, women’s self-rated health is significantly higher than men’s. Thus, gender moderates the effect for frequency of family contact on self-rated health, but only for respondents with new diagnoses.12

Figure 2.

Significant Gender Differences in the Effects of Contact with Family on Self-Rated Health, New Diagnosis Subsample (N=1,113)

Discussion

For decades, although prior studies have revealed the beneficial effects of social support on health, they have also presented inconsistent and complicated gender differences in these effects. Some studies suggest that both women and men benefit from support, others show no gender effects, and still others suggest that men benefit more from marriage and women from close family ties and friends. Despite these efforts to capture effects over the life course, scholarship also remains underdeveloped about how social support affects health at disease onset and as it subsequently progresses. In this article, we considered whether and how cardiovascular disease onset matters for gender differences in the effects of non-marital social support on self-reported health.

Building on prior studies about social support, gender, and health, and responses to stress and shifting resources as social networks change, we developed hypotheses about gender-moderating effects on the relationship between social support and self-rated health and how they differ for respondents with new and pre-existing diagnoses of heart disease. We argue that gender differences in the effects of social support are most likely at the onset of disease. After initial diagnosis, gender is not associated with how social support affects self-rated health. Therefore, women differentially benefit from social support only at the onset of an illness.

Results from an analysis of patients with heart disease are in line with these hypotheses. We began by examining how social support is related to self-rated health, and operationalizing social support using three measures that capture the frequency of contact with family, friends, and neighbors. We then found some support for the first hypothesis. For the full sample, women reported poorer self-rated health than men and gender differentiated the effects for frequency of contact with non-marital family members.

We also estimated separate models for those with pre-existing and new diagnoses. Consistent with Hypotheses 2 and 3, we found gendered effects of family contact but only when the illness is newly diagnosed. When first diagnosis occurred at hospitalization, women, not men, significantly benefitted from having more frequent contact from family. In contrast, among women and men with pre-existing diagnoses, men report better health than women, and having more frequent contacts with friends and neighbors are positively associated with self-rated health, but gender does not differentiate these effects.

We suggest that prior studies’ inconsistent findings about gender differences in the benefits of social support for health are due, in part, to the lack of attention given to the timing of diagnosis. Unlike past studies, we show that understanding how and when gender differentiates the effects of non-marital family contact is linked to disease onset and whether diagnoses are new or old. Different mechanisms may underlie this relationship, assuming network strength dissipates as a disease progresses. For example, frequent contact with others may influence health behaviors immediately after disease onset, but as the disease progresses, such influence is likely to diminish. Inconsistency across prior studies may also be related to differences in the types of social support offered by family vs. friends vs. others. Although social support takes various forms (Cohen and Wills 1985; Berkman et al. 2000; Kanaiaupuni et al. 2005), few studies consider both how different sources of social support are related to differences in health outcomes and how these sources vary as diseases develop and progress. Our findings about frequent non-marital family contact are clear: among those newly diagnosed, women’s (but not men’s) health improves with more family contact.

Less clear, however, is why gender does not differentiate effects for contacts with friends and neighbors. One possible explanation may be that family contact is more salient when patients are admitted to the hospital, which is when the data used in this analysis were collected. Friends and neighbors may not always be aware of a hospitalization immediately after it happens; thus family members are likely to be more important, especially for women who report more frequent family contact than men (see Table 1). Moreover, even after they find out, friends and neighbors may stay away until the situation stabilizes. Future research should consider differences in the roles of groups providing social support, and whether and how groups substitute for one another under certain conditions.

As with all research, this project has important limitations. The first is whether our findings suggest selection or causation. This is a persistent issue in social science studies on health. Although findings suggest there are gendered effects of social support on health, these gendered differences may simply reflect selective processes among men and women who receive and/or give social support. Using longitudinal data in future research will help us understand this issue because such data permit tracking respondents and their social support as health shifts.

Using cross-sectional data is also a limitation because it does not consider normative gendered expectations about being healthy and how they relate to subjective health assessments, whether marriage is less important for people with serious health conditions, and the potential impact of disease severity. All reflect a broader concern about our lack of understanding about social and biological sources of difference in men’s and women’s health (Bird and Reiker 2008). For example, longitudinal data permit an examination of the gendered effects of non-marital received support at early and later disease stages, and the longer-term effects on health as the disease progresses after initial diagnosis. Focusing only on cardiovascular disease is another limitation because it is more prevalent among men who, because they have more overt symptoms and seek treatment, receive more attention from the medical system (Lee et al. 2001). For other diseases, women seek care more readily than men and, if insured, they are also more likely to get routine screenings. Therefore, it is important to understand whether the timing of diagnosis affects how gender is associated with social support for persons with other serious illnesses, such as auto-immune diseases, which are more prevalent among women (Whitacre, Reingold, and O’Looney 1999; Voskuhl 2011; Ngo, Steyn, and McCombe 2014). One final limitation is that the analysis fails to simultaneously capture all possible indicators of social isolation (Cornwell and Waite 2009). Although we control for perceived social support, and for the number of close friends and relatives, our models do not control for perceived loneliness or isolation. These are tasks for future research.

Future research also needs to consider how societal expectations of male and female strength relate to self-reported health assessments. Because society expects men to be strong, powerful, and not sick, men may be more likely than women to report themselves as healthy. Even when hospitalized with compromised health status, men’s own self-rating of health may be better than it is because they are influenced by larger societal expectations about them.

In addition, although studies show that marriage is a special social relationship in which spouses affect their partners’ health behaviors and outcomes (Umberson 1987, 1992; Waite and Gallagher 2000), for our sample of hospitalized patients, marriage is not an independent predictor when other types of social support are measured. Future research must consider what this finding means. It may suggest that researchers should use broader measures of support to understand how social support is associated with chronic illness. Alternatively, it may suggest that marriage is less important as a form of social support for respondents with serious illnesses. One way to assess this is to integrate measures of marital quality which, for older couples, affect cardiovascular risks differently for women and men (Liu and Waite 2014). Not only is poor marital quality and marital loss more strongly linked to women’s cardiovascular risks than men’s, it is also related to women’s diabetic health (Liu et al. 2016). Understanding marital support may also be related to when a spouse/partner is the only person providing support, or when a spouse’s ability to provide good support is complicated by a sudden worsening of their partner’s illness. Thus, marital support may still be important, although it may be one of many types of support that facilitate adaptation to chronic illness. Moreover, because of stressors in certain situations, the effect of marital support may not always be positive.

Finally, although VICS respondents have diagnoses of ACS or CHF, we were unable to assess the potential impact of disease severity, how it varies by gender and whether it is associated with frequency of contact with family, friends, and neighbors. Women are often diagnosed later than men, and are more likely to be under-diagnosed (Loboz-Grudzien and Jaroch 2011). ACS-diagnosed women are also less likely to have invasive procedures, and despite recent growth in the prevalence of ACS among women, they remain under-represented in clinical trials (Stramba-Badiale et al. 2006). Women with ACS also have more risk factors, such as having more co-morbidities and worse prognoses (Elsaesser and Hamm 2004). These factors could contribute to lower self-rated health among women. In addition, women’s longer time to treatment is associated with significantly higher mortality compared to men (Sadowski et al. 2011). Therefore, future work must assess whether women benefit more because they have a disease process that, especially at first diagnosis, is more severe than men.

Together these questions represent a necessary research agenda to understand how gender affects the relationship between social support and health. Our results show that the gendered effects of social support on the health of people with heart disease are contingent on the timing of diagnosis, but they also raise new questions. We expect that collaborative research emphasizing the social and biological foundations of difference in men’s and women’s health will help move this research agenda forward.

Appendix B.

Non-Significant Interaction Models for the Preexisting Diagnosis and New Diagnosis Subsamples

| Preexisting Diagnosis | New Diagnosis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Key Independent Variables | ||||||||||

| Female (ref=male) | −.299* | .122 | −.293** | .121 | −.296** | .122 | −.144 | .154 | −.143 | .154 |

| Extent of Contact with Network | ||||||||||

| Contact with Family | .004 | .045 | .019 | .037 | .021 | .037 | −.002 | .047 | −.002 | .059 |

| Contact with Friends | .101** | .032 | .136*** | .039 | .100** | .032 | .040 | .053 | .038 | .043 |

| Contact with Neighbors | .058* | .026 | .058* | .026 | .073* | .035 | .001 | .034 | −.006 | .043 |

| Interactions | ||||||||||

| Female × Contact with Family | .046 | .069 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Female × Contact with Friends | ---- | ---- | −.089 | ---- | ---- | −.007 | .077 | ---- | ---- | |

| Female × Contact with Neighbors | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | −.033 | .051 | ---- | ---- | .019 | .067 |

| Control Variables | ||||||||||

| Number of Close Relatives | .013 | .020 | .012 | .020 | .013 | .020 | .029 | .027 | .029 | .027 |

| Number of Close Friends | .054* | .021 | .053* | .021 | .053* | .021 | .055* | .027 | .056* | .027 |

| Perceived Social Support | .053*** | .013 | .054*** | .013 | .053*** | .013 | .077*** | .017 | .077*** | .017 |

| Age (years) | .033*** | .005 | .033*** | .005 | .033*** | .005 | .036*** | .007 | .035*** | .007 |

| Age Squared | .001*** | .000 | .001*** | .000 | .001*** | .000 | .001*** | .000 | .001*** | .000 |

| Nonwhite (ref=white) | .232 | .158 | .246 | .158 | .233 | .158 | .346 | .223 | .350 | .223 |

| Married/Partnered (ref=unmarried) | −.197 | .139 | −.210 | .139 | −.205 | .139 | .007 | .171 | .011 | .172 |

| Education (years) | .080*** | .021 | .080*** | .021 | .081*** | .021 | .151*** | .030 | .151*** | .030 |

| Household Income | .129*** | .033 | .129*** | .033 | .127*** | .033 | .152*** | .042 | .152*** | .042 |

| Employed (ref=unemployed) | 1.088*** | .144 | 1.086*** | .144 | 1.092*** | .144 | 1.018*** | .175 | 1.014*** | .175 |

| ACS (ref=CHF) | .669*** | .119 | .676*** | .119 | .673*** | .119 | .061 | .220 | .058 | .220 |

| Constant | .838 | .548 | .541 | .536 | .656 | .535 | .572 | .777 | .639 | .765 |

| R-Square | .237 | .238 | .237 | .197 | .197 | |||||

| N | 1,532 | 1,532 | 1,532 | 1,113 | 1,113 | |||||

Note:

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 (two-tailed tests).

ACS=acute coronary syndrome. CHF=congestive heart failure

NOTES

Women are also more likely to give support, especially emotional support, than men (Belle 1987). Support given by young adult women in a laboratory setting benefitted both women’s and men’s cardiovascular responses by lowering both blood pressure and heart rates, but similar support offered by men had no impact (Glynn et al. 1999). Kahn et al. (2011) find that women offer more support to elderly parents than men.

For studies addressing gendered effects of familial roles, see Waite (1995), Cross and Madson (1997), Bird (1999), Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, and Grayson (1999), Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton (2001).

One early study by B. S. Wallston et al. (1983: 375) noted although few studies reported a clear relationship between social support and disease onset, findings “warrant further research on social support as a moderator of stressors.”

Cannon’s fight or flight response to stress became less salient after Lazarus and Folkman (1984) distinguished between problem- and emotion-focused coping in stress appraisal theory.

Persons with a serious illness may construct social support networks with needed resources, such as others who have (or had) a specific disease (Thoits 2006).

Income accounted for most of the 158 missing observations. Because these values were not missing at random, we did not use multiple imputation.

The Cronbach alpha for the self-rated health measure is .82.

Although the ENRICHD is a 7-item scale constructed from questions that ask about marital status and how often there is someone available to listen, give advice, show affection, help with chores, offer emotional support, and confide in, we use only the 6-item scale and include marital status as a separate variable.

Race is coded as white/nonwhite because we did not have sufficient variation to code it into detailed categories. Only 15 percent of the sample identified as black, Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, or other.

We tested for multicollinearity among these variables by examining variance inflation factors. Because the interaction terms were collinear with their component variables, we centered the continuous variables that are part of the interaction terms to reduce the correlation between them and their component variables (Afshartous and Preston 2011).

We also assessed whether gender differences are significant at different levels of frequency of family, friend, and neighbor contact by generating predicted values of self-rated health by history of diagnosis from: Model 3 in Table 3 and from models in Appendix A. We then ran a macro developed by Andrew Hayes (see (http://www.personal.psu.edu/jxb14/M554/articles/Hayes&Matthes2009.pdf) to test for significant gender differences at three different levels of contact frequency: less than 1 standard deviation from the mean, at the mean, and above 1 standard deviation of the mean – for the two subsamples: those with new and pre-existing diagnoses. We found two significant gender differences for frequency of family contact in the newly diagnosed sample: one at the mean and the other at 1 standard deviation above the mean. Because these were the only two significant gender differences, and are in line with the significant interaction coefficient (Model 3 in Table 3), we do not present the results here but they are available upon request.

References

- Afshartous David and Preston Richard A.. 2011. “Key Results of Interaction Models with Centering.” Journal of Statistics Education 19(3): 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel Carol S., Pearlin Leonard I., and Schuler Roberleigh H.. 1993. “Stress, Role Captivity, and the Cessation of Caregiving.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 34:54–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci Toni C 1985. “Personal Characteristics, Social Support, and Social Behavior.” Pp. 94–128 in Binstock RH, Shanas E (eds.), Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. New York: Van Nostrand. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci Toni C. and Akiyama Hiroko. 1987. “An Examination of Sex Differences in Social Support Among Older Men and Women.” Sex Roles 17(11–12): 737–749. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister Roy F. and Sommer Kristin L.. 1997. “What Do Men Want? Gender differences and two spheres of belongingness: Comment on Cross and Madson.” Psychological Bulletin 122(1): 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belle Deborah. 1987. “Gender differences in the social moderators of stress.” Pp. 257–77 in Rosalind Barnett, with Biener Lois and Baruch Grace (eds.), Gender and Stress. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman Lisa F. and S. Leonard Syme. 1979. “Social Networks, Host Resistance, and Mortality: A Nine-year Follow-up Study of Alameda County Residents.” American Journal of Epidemiology 109(2): 186–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman Lisa F., Leo-Summers Linda, and Horwitz Ralph I.. 1992. “Emotional Support and Survival after Myocardial Infarction: A Prospective, Population-based Study of the Elderly.” Annals of Internal Medicine 117(12): 1003–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman Lisa F., Glass Thomas, Brissette Ian, and Seeman Teresa E.. 2000. “From Social Integration to Health: Durkheim in the New Millennium.” Social Science & Medicine 51: 843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird Chloe E. 1999. “Gender, Household Labor, and Psychological Distress: The Impact of the Amount and Division of Housework.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 40: 32–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird Chloe E. and Rieker Patricia P.. 2008. Gender and Health: The Effects of Constrained Choices and Social Policies. London, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger Niall, Foster Mark, Vinokur Amiram D. and Ng Rosanna. 1996. “Close relationships and adjustment to a Life Crisis: The Case of Breast Cancer.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70: 283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Stephanie L., Nesse Randolph W., Vinokur Amiram D., and Smith Dylan M.. 2003. “Providing Social Support May Be More Beneficial Than Receiving It: Results from a Prospective Study of Mortality.” Psychological Science 14(4): 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable Noriko, Bartley Mel, Chandola Tarani, and Sacker Amanda. 2013. “Friends are Equally Important to Men and Women, But Family Matters More for Men’s Well-being.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 67(2): 166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon Walter B. 1932. The Wisdom of the Body. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier Normand and Ducharme Francine. 2005. “Support Network Transformations in the First Stages of the Caregiver’s Career.” Qualitative Health Research 15(3): 289–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella David, Riley William, Stone Arthur, Rothrock Nan, Reeve Bryce, Yount Susan, Amtmann Dagmar, Bode Rita, Buysse Daniel, Choi Seung, Cook Karon, Robert DeVellis Darren DeWalt, Fries James F., Gershon Richard, Hahn Elizabeth A., Lai Jin-Shei, Pilkonis Paul, Revicki Dennis, Rose Matthias, Weinfurt Kevin, and Hays Ron. 2010. “Initital Adult Health Item Banks and First Wave Testing of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Network: 2005–2008.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63(11): 1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Sheldon. 1988. “Psychosocial Models of Social Support in the Etiology of Physical Disease.” Health Psychology 7: 269–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Sheldon and Wills Thomas Ashby. 1985. “Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis.” Psychological Bulletin 98(2): 310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell Erin York and Waite Linda J.. 2009. “Social Disconnectedness, Perceived Isolation, and Health among Older Adults.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 50(1): 31–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross Susan E. and Madson Laura. 1997. “Models on the Self: Self-Construals and Gender.” Psychological Bulletin 122(1): 5–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis Shannon N. and Greenstein Theodore N.. 2009. “Gender Ideology: Components, Predictors, and Consequences.” Annual Review of Sociology 35: 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler William W. 1980. “Blood Pressure, Relative Weight, and Psychosocial Resources.” Psychosomatic Medicine 45: 527–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsaesser A and Hamm CW. 2004. “Acute Coronary Syndrome: The Risk of Being Female.” Circulation 109: 565–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasure-Smith Nancy, Lesperance Francois, Gravel Ginette, Masson Aline, Juneau Martin, Talajic Martin, and Bourassa Martial G.. 2000. “Social Support, Depression, and Mortality during the First Year after Myocardial Infarction.” Circulation 101: 1919–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallicchio Lisa, Hoffman Sandra C., and Helzlsouer Kathy J.. 2007. “The Relationship between Gender, Social Support, and Health-Related Quality of Life in a Community-Based Study in Washington County, Maryland.” Quality of Life Research 16: 777–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn Laura M., Christenfeld Nicholas, and Gerin William. 1999. “Gender, Social Support, and Cardiovascular Responses to Stress.” Psychosomatic Medicine 61: 234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman Bridget. 2006. “Gender Differences in Depression and Response to Psychotropic Medication.” Gender Medicine 3(2): 93–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havranek Edward P., Mujahid Mahasin S., Barr Donald A., Blair Irene V., Cohen Meryl S., Salvador Cruz-Flores George Davey-Smith, Dennison-Himmelfarb Cheryl R., Lauer Michael S., Lockwood Debra W., Rosal Milagros, Yancy Clyde W.. 2015. “Social Determinants of Risk and Outcomes for Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association.” Circulation, published online August 3, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays Ron D., Bjorner Jakob B., Revicki Dennis A., Spritzer Karen L., and Cella David. 2009. “Development of Physical and Mental Health Summary Scores from the Patient-reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Items.” Quality of Life Research 18(7): 873–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lundstad Julianne, Smith Timothy B., and Bradley Layton J. 2010. “Social Relationships and Mortality Risks: A Meta-analytic Review.” PLOS Medicine 7(7): 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House James S. 1981. Work Stress and Social Support. Reading, MA: Addison, Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- House James S., Robbins Cynthia, and Metzner Helen L.. 1982. “The Association of Social Relationship and Activities with Mortality: Prospective Evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study.” American Journal of Epidemiology 116(1): 123–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House James S., Landis Karl R., and Umberson Debra. 1988. “Social Relationships and Health.” Science 241(4865): 540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Mary Elizabeth and Waite Linda J.. 2009. “Marital Biography and Health at Mid-life.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 50(3): 344–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa R, Matsuda Y, and Eto S. 2014. “The Effects of Giving and Receiving Social Support on Improvement of Health Behavior and Subjective Well-being.” Bulletin of the European Health Psychology Society 16(Supp.). http://www.ehps.net/ehp/index.php/contents/issue/view/23 [Google Scholar]

- Juster F. Thomas and Suzman Richard. 1995. “An overview of the Health and Retirement Survey.” Journal of Human Resources 30(suppl): S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn Joan R., McGill Brittany S., and Bianchi Suzanne M.. 2011. “Help to Family and Friends: Are There Gender Differences at Older Ages?” Journal of Marriage and Family 73(1): 77–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaiaupuni Shawn Malia, Donato Katharine M., Thompson-Colon Theresa, and Stainback Melissa. 2005. “Counting on Kin: Social Networks, Social Support, and Child Health Status.” Social Forces 83(2): 1137–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser Janice K. and Newton Tamara L.. 2001. “Marriage and Health: His and Hers.” Psychological Bulletin 127(4): 472–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus Richard S. and Folkman Susan. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Patrick Y., Alexander Karen P., Hammill Bradley G., Pasquali Sara K., Peterson Eric D.. 2001. “Representation of elderly persons and women in published randomized trials of acute coronary syndromes.” JAMA 286: 708–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Haifeng, Ji Yang, and Chen Tianyong. 2014. “The Roles of Different Sources of Social Support on Emotional Well-Being among Chinese Elderly.” PLoS One 9(3): 10.1371/journal.pone.0090051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Hui. 2012. “Marital Dissolution and Self-Rated Health: Age Trajectories and Birth Cohort Variations.” Social Science & Medicine 74: 1107–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Hui and Waite Linda. 2014. “Bad Marriage, Broken Heart? Age and Gender Differences in the Link between Marital Quality and Cardiovascular Risks among Older Adults.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 55: 403–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Hui, Waite Linda, and Shen Shannon. 2016. “Diabetes Risk and Disease Management in Later Life: A National Longitudinal Study of the Role of Marital Quality.” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 71(6): 1070–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loboz-Grudzien Krystyna and Jaroch Joanna. 2011. “Women with Acute Coronary Syndromes have a Worse Prognosis – Why? The Need to Reduce ‘Treatment-seeking Delay.’” Cardiology Journal 18(3): 219–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Ye, Hawkley Louise C., Waite Linda J., and Cacioppo John T.. 2012. “Loneliness, Health, and Mortality in Old Age: A National Longitudinal Study.” Social Science & Medicine 74(6): 907–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyyra Tiina-Mari and Heikkinen Riitta-Liisa. 2006. “Perceived Social Support and Mortality in Older People.” Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 61B(3): S147–S152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers Abby G., Salanitro Amanda, Wallston Kenneth A., Cawthon Courtney, Vasilevskis Eduard, Goggins Kathryn M., Davis Corinne M., Rothman Russell L., Castel Liana D., Donato Katharine M., Schnelle John F., Bell Susan P., Schildcrout Jonathan S., Osborn Chandra Y., Harrell Frank E., and Kripalani Sunil. 2014. “Determinants of Health after Hospital Discharge: Rationale and Design of the Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS).” BMC Health Services Research 14: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca Lori, Barrett-Connor Elizabeth, and Kass Wenger Nanette. 2011. “Sex/Gender Differences in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: What a Difference a Decade Makes.” Circulation 124: 2145–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema Susan, Larson Judith, and Grayson Carla. 1999. “Explaining the Gender Difference in Depressive Symptoms.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77(5): 1061–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo Shyuan T., Steyn Frederik J., and McCombe Pamela A.. 2014. “Gender Differences in Autoimmune Disease.” Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 35(3): 347–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth-Gomér Kristina, Rosengren Annika, and Wilhelmsen Lars. 1993. “Lack of Social Support and Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease in Middle-Aged Swedish Men.” Pyschosomatic Medicine 55: 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry Brea L. and Pescosolido Bernice A.. 2012. “Social Network Dynamics and Biographical Disruption: The Case of “First-Timers” with Mental Illness.” American Journal of Sociology 188(1): 134–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart Martin and Duberstein Paul. 2010. “Depression and Cancer Mortality: A Meta-analysis.” Pyschological Medicine 40: 1797–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers Edward A. and Bultena Gordon L.. 1976. “Sex Differences in Intimate Friendships of Old Age.” Journal of Marriage and Family 38(4): 739–747. [Google Scholar]

- Reblin Maija and Uchino Bert N.. 2008. “Social and Emotional Support and its Implication for Health.” Current Opinion in Psychiatry 21(2): 201–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi Alice S. 2004. “Social responsibility to Family and Community” Pp. 550–85 in Orville Gilbert Brim Carol D. Ryff, and Kessler Ronald C. (eds.), How Healthy Are We?: A National Study of Well-being at Midlife. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski M, Janion-Sadowska AA, Gasior M, Gierlotka M, Janion M, and Polonski L. 2011. “Gender-Related Benefit of Transport to Primary Angioplasty: Is It Equal? Cardiology Journal 18: 254–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman Teresa E. 1996. “Social Ties and Health.” Annals of Epidemiology 6: 442–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker Sally A. and Robin Hill D. 1991. “Gender Differences in Social Support and Physical Health.” Health Psychology 10(2): 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shye Diana, Mullooly John P., Freeborn Donald K., and Pope Clyde R.. 1995. “Gender Differences in the Relationship between Social Network Support and Mortality: A Longitudinal Study of an Elderly Cohort.” Social Science & Medicine 41(7): 935–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha Seema and Tremmel Jennifer A.. 2007. Sex differences in acute coronary syndrome Chapter 6 in Symposium in Cardiac and Vascular Medicine (SIS Yearbook): 1–8. http://www.sis.org/docs/2007Yearbook_Ch6.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer Susan B., Llabre Maria M., Ironson Gail H., Gellman Marc D., and Schneiderman Neil. 1992. “The Influence of Social Situations on Ambulatory Blood Pressure.” Psychosomatic Medicine 54: 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stramba-Badiale Marco, Fox Kim M., Priori Silvia G., Collins Peter, Daly Caroline, Graham Ian, Jonsson Benct, Schenck-Gustafsson Karin, and Tendera Michal. 2006. “Cardiovascular Diseases in Women: A Statement from the Policy Conference of the European Society of Cardiology.” European Heart Journal 27: 994–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Shelley E., Laura Cousino Klein Brian P. Lewis, Gruenewald Tara L., Gurung Regan A.R., and Updegraff John A.. 2000. “Biobehavioral Responsees to Stress in Females: Tend-and-Befriend, Not Fight-or-Flight.” Psychological Review 107(3): 411–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits Peggy. 1995. “Stress, Coping, and Social Support Processes: Where Are We? What Next?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35 (Extra Issue): 53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits Peggy. 2006. “Personal Agency in the Stress Process.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 47(4): 309–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits Peggy. 2011. “Mechanisms Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 52(2): 145–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Patricia A. 2010. “Is It Better to Give or to Receive? Social Support and the Well-being of Older Adults.” Journal of Gerontology 65B(3): 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino Bert N. 2004. Social Support and Physical Health: Understanding the Health Consequences of Our Relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino Bert N. 2006. “Social Support and Health: A Review of Physiological Processes Potentially Underlying Links to Disease Outcomes.” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 29(4): 377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino Bert N., Bowen Kimberly, Carlisle McKenzie, and Birmingham Wendy. 2012. “Psychological Pathways Linking Social Support to Health Outcomes: A Visit with the ‘Ghosts’ of Research Past, Present, and Future.” Social Science & Medicine 74(7): 949–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino Bert N., Cacioppo John T., and Kiecolt-Glaser Janice K.. 1996. “The Relationship Between Social Support and Physiological Processes: A Review with Emphasis on Underlying Mechanisms and Implications for Health.” Psychological Bulletin 119(3): 488–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra. 1992. “Gender, Marital Status, and the Social Control of Health Behavior.” Social Science & Medicine 34(8): 907–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra and Montez Jennifer Karas. 2010. “Social Relationships and Health: A Flashpoint for Health Policy.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51(Suppl): S54–S66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Chen Meichu D., House James S., Hopkins Kristine, and Slaten Ellen. 1996. “The Effect of Social Relationships on Psychological Well-Being: Are Men and Women Really So Different?” American Sociological Review 61(5): 837–857. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Crosnoe Robert, and Reczek Corinne. 2010. “Social Relationships and Health Behaviors across the Life Course.” Annual Review of Sociology 36: 139–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jr Vaglio., Mark Conard Joseph, Poston Walker S., O’Keefe James, Haddock C. Keith, House John, and Spertus John A.. 2004. “Testing the Performance of the ENRICHD Social Support Instrument in Cardiac Patients.” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2(24) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC434528/pdf/1477-7525-2-24.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voskuhl Rhonda. 2011. “Sex Differences in Autoimmune Diseases.” Biology of Sex Differences 2(1): 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite Linda J. 1995. “Does Marriage Matter?” Demography 32(4): 483–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite Linda J. and Gallagher M. 2000. “The Case for Marriage: Why Married People are Happier, Healthier, and Better Off Financially.” New York NY: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi Chizuko and Donato Katharine M.. 2006. “Does Caregiving Increase Poverty among Women in Later Life? Evidence from the Health and Retirement Survey.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 47(3): 258–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walen Heather R. and Lachman Margie E.. 2000. “Social Support and Strain from Partner, Family, and Friends: Costs and Benefits for Men and Women in Adulthood.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 17(1): 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wallston Barbara Strudler, Alagna Sheryle Whitcher, DeVellis Brenda McEvoy, and DeVellis Robert F.. 1983. “Social Support and Physical Health.” Health Psychology 2(4): 367–391. [Google Scholar]

- Wethington Elaine, McLeod Jane, and Kessler Ronald C.. 1987. “The Importance of Life Events for Explaining Sex Differences in Psychological Distress.” Pp. 144–154 in Rosalind Barnett, with Biener Lois and Baruch Grace (eds.), Gender and Stress. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitacre Caroline C., Reingold Stephen C., and O’Looney Patricia A.. 1999. “A Gender Gap in Autoimunity.” Science 283(5406): 1277–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams Redford B., Barefoot John C., Califf Robert M., Haney Thomas L., Saunders William B., Pryor David B., Hlatky Mark A., Siegler Ilene C., and Mark Daniel B.. 1992. “Prognostic Importance of Social and Economic Resources among Medically Treated Patients with Angiographically Documented Coronary Artery Disease.” JAMA 267(4): 520–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Zhenmei and Hayward Mark D.. 2006. “Gender, the Marital Life Course, and Cardiovascular Disease in Late Midlife.” Journal of Marriage and Family 68(3): 639–657. [Google Scholar]