Abstract

Background:

The level of occupational violence against nurses increases from 68.8 to 98.6 percent, which is a considerable rate among healthcare settings. To create a safe environment for patient care in the emergency department (ED), a comprehensive program for the prevention of violence is necessary. The aim of this study was to plan a workplace violence prevention program (WVPP) to reduce the level of patients' and their families' violence against nurses.

Materials and Methods:

The present study is a quantitative part of a participatory action research project conducted in an 18-month period from October 2012 to May 2014 in an ED of Iran. In the diagnosing phase, we used quantitative and qualitative approaches. The second and third phases were assigned to design and implementation of WVPP involving a combination of educational and managerial interventions. In the evaluation phase, frequencies of patients' and their families' violence against nurses and nurses' fear of violence were measured.

Results:

Mc-Nemar test showed that 85.70% (n = 42) frequencies of verbal violence before implementing WVPP significantly decreased to 57.10% (n = 28) after implementing WVPP (p = 0.007). Statistical-dependent t-test (p < 0.001) indicated a significant difference in the mean (SD) scores of nurses' fear of violence before 46.10 (8.3) and after intervention 34.30 (4.6).

Conclusions:

Applying educational and managerial interventions was effective in reduction of workplace violence. Thus, it is recommended to include a combined approach in designing WVPP in cultures similar to Iran and pay attention to effective interactions with patients' family.

Keywords: Emergencies, Iran, nurses, policy, workplace violence

Introduction

Violence in the emergency departments (ED) is one of the most important and frequent concerns of emergency practitioners.[1] To create a safe environment for patient care in the ED, there is a need for a comprehensive program for prevention of patient/family violence against nurses.[2] Studies showed that violence was a complex and culturally bound issue. One of the most important factors in designing a successful program is to ensure meeting the unique needs of the intended organization.[3,4] Among healthcare settings, EDs are at the highest risk of violence where nurses are three times more likely to experience violent events as compared with other employees.[5] The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data shows that between 2011 and 2013, workplace assaults ranged from 23,540 and 25,630 annually, with 70 to 74% occurring in healthcare and social service settings.[6]

The ED is the incoming door to all other hospital wards. Emergency nurses are practicing on the front line of patient care.[7] In addition, many well-known problems such as hospital overcrowding, long waiting times, shortage of emergency nurses,[8] considering nursing as uncaring, and misconceptions regarding the staff behavior can result in ED violent incidents.[9] Thus, aggression and violence in EDs are reported to be highly frequent.[10,11]

The 2006 position statement of the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) entitled “Violence in the Emergency Care Setting” states, “Health care organizations are responsible for providing a safe and secure environment for their employees and the public.”[12] The necessity of a comprehensive violence prevention program with the objective of establishing a safe working environment to care for patients in EDs seems almost obvious.[2,13] However, a number of governments have so far announced a violence prevention program. There are several main stages to any workplace violence prevention program (WVPP): Management commitment and employee participation, Worksite analysis, Hazard prevention and control, Safety and health training, and Recordkeeping and program evaluation.[6,14,15,16]

One of the most important factors in creating a successful program is to ensure that it meets the unique needs of the organization. As worksites for healthcare providers and related occupations vary in purpose, size, and complexity, WVPP should be designed to specifically target the unique nature and varied needs of each organization.[3] These recommendations are not a “model program” or a rigid package of violence prevention steps uniformly applicable to all establishments. Employers may use a combination of strategies recommended in this document depending on their particular context.[15]

Violence and WVPPs in Iran: According to the studies conducted in Iran, the level of occupational violence against nurses increases from 68.8 to 98.6 percent, which is a considerable rate.[10,17,18] There is an obvious lack of organized educational programs on violence control and management and ways to appropriately treat violent patients and their families in Iran's healthcare system. Furthermore, no rules and regulations have been approved in this regard to monitor and coordinate the performance of healthcare institutes with the aim of reducing the violence rate.[19] In addition, healthcare professionals, particularly nurses, are merely recommended to keep calm and practice self-composure when treating violent patients.[20,21]

Imam Reza Hospital is one of the biggest medical centers of Mashhad University of medical science to provide healthcare and educational services. The new ED of this hospital, which has been recently built, is the biggest ED in Eastern of Iran. Researchers have found that the rate of violence against nurses remains high and prevention efforts are low. Although there are numerous studies showing that ED violence is a prevalent and serious problem for healthcare workers, there is a lack of published evaluations of interventions aimed at reducing this alarming trend in Iran. We used an action research approach that emphasizes on a close collaboration among researchers, hospital staff, and administrators.[22] The members of this research consisted of an assistant professor as the leader of an academic-service partnership trip to expand patient and family education program at the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Head of the ED, head of the emergency ward, head nurse, and a master student of nursing working in the ED. The above partnership brings together these primary stakeholders to perform action research as a problem-solving process with the stage of assessment, implementation, and evaluation to increase the success rate of the violence prevention program. The aim of this study was to plan a workplace violence prevention program (WVPP) to reduce the level of patients' and their families' violence against nurses using an action research.

Materials and Methods

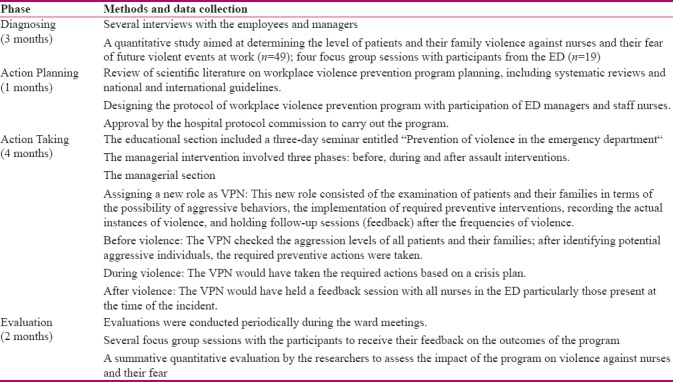

This study is a quantitative part of participatory action research that carried out in the ED of Imam Reza's hospital during an 18-month period from October 2012 to May 2014. Imam Reza's hospital is a province hospital in Mashhad-Iran. The method used in this study was a participatory action research design with cyclical activities involving diagnosis, action planning, action taking, and evaluation and specifying learning.[22] Table 1 presents the specific methods used in different phases of the action research. To critically review the existing situation, we started the diagnosis phase with a working group consisting of the researchers, chief physicians of the department (n = 2), the clinical supervisors (n = 3), the head nurse and in-charge nurses (n = 5), clinical nurses (n = 8), and the manager of the security department (n = 1). The number of participants required to conduct the research was calculated using a sample size formula to compare two proportions through carrying out a preliminary study. The highest sample size was estimated using the values of verbal violence. Thus, with verbal violence before (p1 = 0.04), after (p2 = 0.09), and with 95% confidence interval and power of 80% sample, the size was calculated 44.

Table 1.

Methods of data collection and results of the action research phases

The inclusion criteria for nurses were having at least a 4-month work experience in the ED and having a bachelor or master's degree in nursing, and exclusion criteria consisted of having stressful events such as divorce, death of relatives, immigration or severe accident, leaving a job or transfer, and absence in more than one day of training sessions. The purpose of the focus groups was to determine whether the strategies planned for intervention were relevant, acceptable, feasible, and comprehensive.

The first phase of this research (diagnostic phase) aimed at determining the level of patients and their family violence against nurses. This stage of the study helps us evaluate the problem in our EDs and recognizes the major sources of violence and the common action that nurses take against violence. In this phase, we performed a cross-sectional descriptive study on 68 nursing staff in October 2012.[11] We assessed the workplace violence frequencies against nurses using a self-administered questionnaire which was adjusted by researchers regarding/considering WPV issues in the healthcare settings from the International Labor Office, the International Council of Nurses, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Public Services International (2003).

The level of nurses' fear of violence frequencies was assessed as well. For this purpose, the Fear of Workplace Violence over the Next Year Scale developed by Schat and Kelloway (2000) was translated and used; it comprises 12 propositions on a seven-point Likert scale from “completely disagree” to “completely agree.” Nurses anticipate their fear of workplace violence in the future by choosing a response from 1 to 7 on the Likert scale. A total score of 12 on the scale represents minimum fear, while a score of 84 indicates maximum fear.

The results of the diagnosing phase showed that all nurses were exposed to verbal violence at least once during the last year (14.7% once, 69.1% sometimes, and 16.2% always), while 22.1% had experienced physical violence during the same time. The most common cause of violence against nurses was patients' relatives and most of the nurses had not taken any action against them. More than half of the nurses stated that they did not report the incident as they thought it was ineffective; they also stated that there was no specific action taken by their supervisors to identify the cause of violence. In addition, tracking the reported violence has often been unsatisfactory.[11]

The next step of the diagnosing phase involved the use of a focus group to gather information from employees and managers regarding their beliefs on a certain violent event and identify the strategies that they believed to be beneficial and sustainable in their work settings. We invited “the working group” and held four sessions in the conference hall of the ward. During the first and the second focus group sessions, the data of the descriptive study were presented and the participants were asked to express their experiences regarding the main reason behind the frequencies of violence. The first researcher made notes of the main issues raised in discussions. Based on these two sessions, the main problem was identified as to originate from the lack of knowledge and skills of the nursing staff with respect to stress and conflict management, and communication skills especially with aggressive patients and their families. According to our participants' experiences, the second major reason that put the nursing staff at the risk of violence was the lack of guidelines and recommendations from the government and professional organizations to run WVPP. Therefore, the participants and the researchers decided to develop a two-part WVPP that would consist of educational and managerial sections.

During the third and fourth sessions (action planning phase), the framework of WVPP was designed. The researchers constructed the overall framework of a prevention program on the basis of a series of literature reviews. This framework was presented in the focus group session as a template, while all participants shared their ideas on individual components of the programs. At the end of these sessions, decision was made to administer a WVPP in the ED. The program involved a combination of the educational and managerial intervention: the educational component consisted of a three-day seminar. The working group has some informal verbal communications during phases of action research. They reviewed reports during doctor's visits, doctors, and nursing rounds.

The principal constituents of the managerial component to the WVPP included the assigning of a new role as violence prevention nurse (VPN); this new role consisted of the examination of patients and their families in terms of the possibility of aggressive behaviors, the implementation of required preventive interventions, recording the actual instances of violence, and holding follow-up sessions (feedback) after the frequencies of violence.

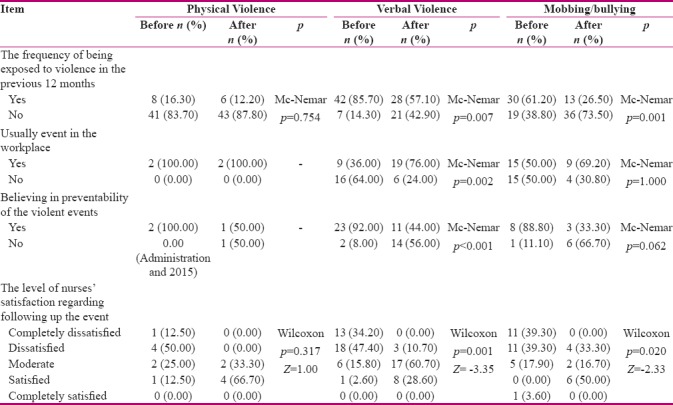

At the end of action planning phase, we assessed again WVPP frequencies against nurses. These data provide a baseline to compare with the results of the evaluation phase [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of the nurses working in ED, according to the amount of violence and the type of reaction to violence

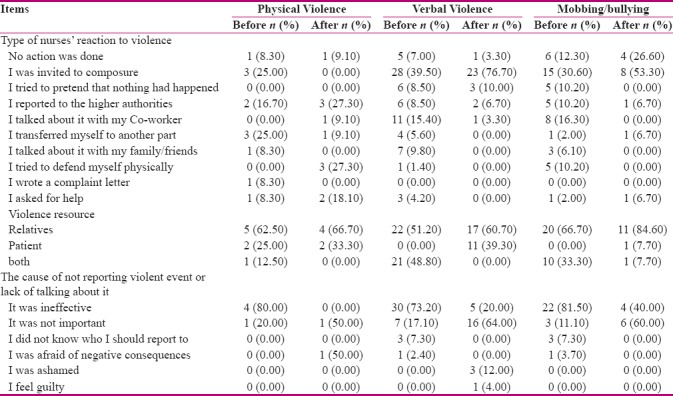

Table 3.

Type of nurses’ reaction to violence

The third phase of this research (action taking) included the implementation of the two-part WVPP; the educational and managerial.continuing education program included a three-day seminar titled “Prevention of violence in the emergency plan.” The main purpose of the educational seminar was to familiarize nurses with workplace violence and its dimensions, to train nurses on anger management, stress management and conflict resolution, as well as briefing them on the WVPP. The managerial part of the program was designed and implemented in the three stages of before, during, and after the violence interventions. In before violence intervention stage, the VPNs checked the aggression levels of all patients and their families in terms of the possible signs of violence at the beginning of each work shift using the alarming signs of an imminent violence form; after identifying potential aggressive individuals, the required preventive actions were taken to manage each instance of violence according to the instructions. The actions consisted of informing all nurses in the ward about the possibility of aggression by patients and their families and offering recommendations on taking the instructed communicative actions during the intervention educational program, facilitating the care process to shorten the waiting hours of potential violent patients, making the required explanations by the medical team to the patient's family about the treatment process, and giving on time information to the families on any sudden change in their patient's status.

This is followed by the VPNs recording the identified potential aggressive individuals as well as the actions taken to prevent the incident in the daily report log of the shift supervisors while reporting to the next supervisor.

During violence intervention, if the violent incident occurred in the ward, the VPNs would have taken the required actions based on a crisis plan (managing the instance of aggression, helping the victimized nurse, calling in the security guards if necessary, and informing the on-call supervisor to take necessary actions), while recording the violence cases using the violence report form was followed by receiving confirmation from the eye-witnesses.

In the After Assault intervention, as soon as possible after the incident, the VPNs would have held a feedback session with all nurses in the ED particularly those present at the time of the incident. Due to the crowdedness of the ED and the short times of nurses, the feedback sessions were usually held during the nurses' resting hours. These sessions aimed at scrutinizing the violent incident; the victimized nurses talked to their co-workers about the incident, while at the same time the reasons behind the act of aggression were investigated. Finally, the session proceedings were recorded in the feedback session recording from which the attendants in the session signed. Depending on the reason behind the frequencies, certain preventive measures were then suggested for taking in the ward based on the ideas of the attendants.

In the course of the program, frequent sessions were held with the team members, the VPNs, the heads of the unit (Chief physician of the department, the clinical supervisors, the head nurse, and the manager of the security department), and the researchers, where the program was constantly revised and balanced. For example, given that many instances of violence were due to the security guards' unfitting treatment of patients' family and considering the significance of the hospital's security units in preventing and managing aggression, a WVPP was also designed exclusively for the security guards. The content of this educational program included: definition of violence, types of violence, sources of violence, alarming signs of imminent violence, communication and its types, and precautions in treating violent individuals.

Given that one of the other major sources of aggressive behaviors in patients and their families was lack of awareness about the physical environment and the ward regulations and their frequent questions of the ED staff as strengthening the possibility of violence frequencies, a series of written guidelines was designed wherein the rules, and regulations of the ED in terms of reception and prioritization of the emergency patients were presented to patients and their families. Also, an image file, shown on the monitors in the ED lobby, was prepared by the researchers to familiarize the clients with different parts of the ED.

In addition, during the intervention process, educational guidelines were installed all over the ED (the resting room, the entrance, the working room, the nursing station, and the security booth) as posters and fliers to constantly recite the instructions about the important points on communicative methods and how to treat violent individuals.

In addition, the VPNs submitted their reports of the existing obstacles on the way of the implementation of the program to the chief nurse shortly after the start of WVPP, and the chief nurse's response to the appropriate measures to resolve these complications was issued to the shift supervisors.

During evaluation phases/between each cycles of the study, the effectiveness of conducting the program was examined via two methods. First, the impacts and consequences of the administration of WVPP from the point of view of the ward managers and nursing professionals were identified and inspected. Second, in a collective evaluation, four months after the implementation, the effectiveness of the program on the level of violence against nurses and their fear of the frequencies of violence was re-examined. Data were analyzed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 16, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical considerations

After explanation of the research stages, an informed written consent was obtained from the participants. This study was derived from a research project and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (IR. MUMSREC.1392.300).

Results

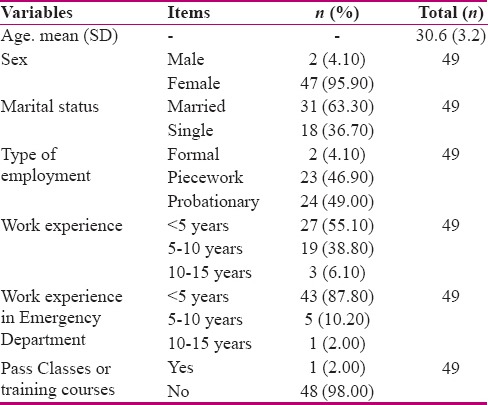

The demographic information of the nursing professionals who participated in the study is given in Table 4. The results indicate the frequency distribution of verbal violence rate and mobbing/bullying against nurses before and after the implementation of WVPP, based on Mc-Nemar's test, was a significant difference for verbal violence (p = 0.007) and for mobbing/bullying (p = 0.001). Also, Student-dependent t-test showed a significant difference between the mean score of nurses' fear of violence before the intervention 46.10 (8.30) with mean score of nurses' fear of violence after the intervention 34.30 (4.60) (p < 0.001). Moreover, according to Mc-Nemar's test, frequency distribution of physical violence against nurses before and after the implementation of WVPP was not significant (p = 0.754) as well [Table 2] and the mean score of concern about the risk of violence at work before the intervention 3.40 (1.10) with mean score of concern about the risk of violence after the intervention 3.00 (0.90) was statistically significant (p = 0.006).

Table 4.

Demographic information of the participating nursing staff

In addition, compared to before the implementation of the program, more nurses (76.00%, n = 19) believed that verbal violence is not a common practice in their workplace, while 56.00% (n = 14) thought it was avoidable as well. Also, after running the program, more than half of the nurses (60.70%, n = 17) evaluated their satisfaction of following up the incident as “moderate,” whereas the level of satisfaction of the violent incident follow-up was much lower (47.40%, n = 18) before the program where they had stated that violence is a common workplace practice and unavoidable (92.00%, n = 23). Furthermore, after intervention, more than half of the nurses stated that they do not report the incident as they think it is ineffective; they also stated that there was no specific action taken by the supervisor to identify the cause of violence. In addition, following up the reported violence has often been unsatisfactory [Table 3].

The results of logistic regression analysis to determine the relationship between individual and background variables (Sex, Marital status, Type of employment, Work experience, Work experience in ED, and Pass Classes or training courses) on the frequency of violence showed no significant relationship between these variables and the frequency of violence.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to plan a workplace violence prevention program to reduce the level of patients and their family violence against nurses. One advantage was that we were able to adapt the implementation of WVPP to our particular setting and tailor the implementation strategies. In this way, we empowered the nurses that participated to play the role of a VPN. It was the nurses themselves who proposed to use WVPP as a means to provide a safe caring environment.

It was evident that the working group and nurses were concerned about violence in the ED and perceived the problem as increasing. Most participants expressed their dissatisfaction with the perception that violence against healthcare workers was often accepted by the administration, managers, and employees as part of the job.

According to the results of the study, first, the level of verbal violence, mobbing/bullying against nurses, their fear of violence as well as their concerns significantly decreased after the implementation of the WVPP. Second, the nurses came to believe that violent incidents are preventable and manageable. Third, they ceased to consider violent incidents as a common workplace practice and as a routine part of their job and they stated that they are well aware of violence reporting techniques and that they are capable of preventing and managing any act of aggression. Based on the above findings, it seems safe to claim that the educational component of WVPP could increase the nurses' understanding of violence management and the ways to prevent workplace violence, as it was at this stage where the nurses received the required instructions on how to treat violent patients and the techniques to prevent and handle the violent incident. The results of other studies in this area confirm the above conclusion as well. In a study on the effectiveness of another aggression management training program, Oostrom and Mierlo (2008) discovered that training results in stable changes in people's understanding and behavior; in addition, they found out that aggression management training can efficiently deepen people's insight into aggression and their ability to adjust to unfavorable working conditions.[23] In our study, as well, the amount of nurses' fear of and concern for violence reduced and they came to accept that violent incidents are avoidable and manageable, a fact that indicates a change in people's insight into aggression management. In another study on the impact of a one-day training program for emergency nurses on managing potential violent situations, Deans (2004) found that first, the number of violent scenarios was calculated in the course of three months, which demonstrated a relative reduction; second, the participants experienced higher levels of self-confidence and cold-bloodedness after the violent incident and they took part in managing assaulting situations as a team member.[24]

Given that healthcare managers are responsible for providing a safe working environment for their employees as well as designing WVPP tailored to the unique needs and properties of their organizations and considering that we discovered, during the diagnosis stage, that there is a lack of rules and regulations in our organization to guide the way to prevent and manage violent incidents and the nurses are merely encouraged to observe self-composure while treating aggressive patients, the managerial component was designed, in addition to the educational section, with the active participation of the nurses themselves, based on which: first, certain guiding policies on treating aggressive patients were prepared and distributed among the employees; second, the new role of VPN was defined for the participant nurses, and in this role, they can identify potentially violent patients and take measures to facilitate and accelerate the process of treatment.

As described earlier, the purpose of the focus groups was to determine whether the strategies planned for intervention were relevant, acceptable, feasible, and comprehensive. The planned strategy was supported by all participants in the four focus groups. Suggested strategies included better communication, increased facilities of comforting, staffing issues, enhanced and more frequent training for the staff and managers, accelerated organizational processes, and separating patients early when an obvious act of aggression is observed.

Based on the above findings and with the help of the nursing staff, a combined educational/managerial WVPP was designed. The educational component aimed at boosting the nurses' knowledge and skill in identifying, preventing and managing any instance of violence, whereas the managerial section paid special attention to the examination of signs of violence within the patients' family by the VPN making close bonds with the families of potential violent patients, trying to avoid the frequencies of aggression by providing accurate information and facilitating the treatment process.

Although our study design was suited to our objective, participation of patients' care givers could improve the results. The participation of patients' care givers in the ED was not possible and it was limitation of our study.

Conclusion

With an action research design and formation of working group for WVPP at ED of a hospital, we were capable of adjusting the administration of violence prevention to our particular medical context and tailor implementation strategies. The results showed that the administration of educational and managerial interventions is an effective strategy to reduce workplace violence. In addition, managing the violent event and its subsequent interventions reduced the risk of mental and physical side-effects of violence in our nurses. Thus, it is recommended to include a combined approach in designing workplace violence prevention programs in societies and cultures similar to our context in Iran and to pay special attention to effective interactions of nurses with patients' families.

Financial support and sponsorship

Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

Conflicts of interest

Nothing to declare.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all participants who voluntarily participated in this study. The present paper was approved by the research department [grant number 921006] of Mashhad Medical Science University. The authors hereby express their gratitude toward the authorities of Mashhad Medical Science University for sponsoring the study and the authorities of the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery and participants for their valuable support.

References

- 1.Wei CY, Chiou ST, Chien LY, Huang N. Workplace violence against nurses–Prevalence and association with hospital organizational characteristics and health-promotion efforts: Cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;56:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillespie GL, Gates DM, Kowalenko T, Bresler S, Succop P. Implementation of a comprehensive intervention to reduce physical assaults and threats in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2014;40:586–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau JB, Magarey J, Wiechula R. Violence in the emergency department: An ethnographic study (part II) Int Emerg Nurs. 2012;20:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Ali NM, Al Faouri I, Al-Niarat TF. The impact of training program on nurses' attitudes toward workplace violence in Jordan. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30:83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jabbari-Bairami H, Heidari F, Ghorbani V, Bakhshian F. Workplace Violence: A Regional Survey in Iranian Hospitals' Emergency Departments. Int J Hosp Res. 2013;2:11–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Administration OSHA. Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers. U.S Depatrment of labor occupational safety and health administration. OSHA 3148-06R. 2016. [Last accessed on 2016 may 14]. Available from: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3148.pdf .

- 7.Fute M, Mengesha ZB, Wakgari N, Tessema GA. High prevalence of workplace violence among nurses working at public health facilities in southern Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2015;14:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12912-015-0062-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Speroni KG, Fitch T, Dawson E, Dugan L, Atherton M. Incidence and cost of nurse workplace violence perpetrated by hospital patients or patient visitors. Emerg Nurs. 2014;40:218–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gacki SJ, Juarez A, Boyett L, Homeyer C, Robinson L, MacLean S. Violence against nurses working in US emergency departments. J Healthc Prot Manage. 2010;26:81–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esmaeilpour M, Salsali M, Ahmadi F. Workplace violence against Iranian nurses working in emergency departments. Int Nurs Rev. 2011;58:130–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heshmati Nabavi F, Reihani HR. Evaluation of violence of patients and their families against emergency nurses of Imam Reza Central Hospital in Mashhad. Iran J Crit Care Nurs. 2015;8:227–36. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gates D, Gillespie G, Smith C, Rode J, Kowalenko T, Smith B. Using action research to plan a violence prevention program for emergency departments. J Emerg Nurs. 2011;37:32–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McPhaul K, London M, Murrett K, Flannery K, Rosen J, Lipscomb J. Environmental Evaluation for Workplace Violence in Healthcare and Social Services. J Saf Res. 2008;39:237–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angland S, Dowling M, Casey D. Nurses' perceptions of the factors which cause violence and aggression in the emergency department: A qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2014;22:134–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 3153-12R O. Recommendations for Workplace Violence Prevention Programs in Late-Night Retail Establishments. Labor USDo, editor. 2009. [Last accessed on 2017 May 18]. Available from: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3153.pdf .

- 16.Stokowski LA. Nurses M, editor. Violence: Not in My Job Description. 2010. [Last accessed on 2017 May 15]. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/727144 .

- 17.Rahmani A, Hassankhani H, Mills J, Dadashzadeh A. Exposure of Iranian emergency medical technicians to workplace violence: A cross-sectional analysis. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24:105–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2011.01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghodsbin F, Dehbozorgi Z, Tayari N. Prevalence of violence against nurses. Bimonthly Scientific Journal. J Med Res. 2007;78:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Najafi F, Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Dalvandi A, Ahmadi F, Rahgozar M. Workplace violence against Iranian's nurses: A systematic review. Health Promot Manage. 2014;3:72–85. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasani A, Zaheri MM, Abbasi M, Saeedi H, Hosseini M, Fathi M. Incidence rate of physical and verbal violence inflicted by patients and their companions on the emergency department staff of Hazrate-e-Rasoul Hospital in the Fourth Trimester of the year 1385. Iran Univ Med Sci. 2010;16:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teimoorzadeh E, Rashidian A, Arab M, Ghasemi M. Measuring nurses' exposure to violence in a large educational hospital in Tehran. J Sch Health Health Res Inst. 2010;7:41–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Susman GI, Evered RD. An assessment of the scientific merits of action research. Administrative science quarterly. 1978;23:582–603. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oostrom JK, van Mierlo H. An Evaluation of an aggression management training program to cope with workplace violence in the healthcare sector. Nurs Health. 2008;31:320–8. doi: 10.1002/nur.20260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deans C. The effectiveness of a training program for emergency department nurses in managing violent situations. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2004;21:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]