Abstract

Background:

Qualitative research methods can help investigators ascertain the depth of people's needs and their perceptions. This study was designed to describe mothers' experiences and perceptions of lay doula services during labor and delivery.

Materials and Methods:

This study was conducted using a qualitative approach and conventional procedures of content analysis. The participants consisted of 13 nulliparous women at three hospitals affiliated with Zahedan University of Medical Sciences in 2016. Data were collected using face-to-face semi-structured interviews. Purposive sampling continued until data saturation was ensured. All interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed in verbatim.

Results:

Participants' experiences were categorized into 11 subthemes and five major themes including (1) achieving self-esteem and empowerment, (2) more trust in God, (3) promoting mental health of the mother, (4) willingness toward normal childbirth, and (5) lay doula as a listener and perceiver.

Conclusions:

In our study, the mothers evaluated the presence of a lay companion as an effective helper during childbirth and someone who promoted a remarkable willing toward normal childbirth. Healthcare professionals must be cognizant of the needs, values, beliefs, preferences, and emotional well-being of disadvantaged women during labor and delivery in poverty-stricken areas of Iran. Also, this study highlighted that it is important to include the perspective of support persons (such as husbands) in research design of future studies.

Keywords: Doulas, experiences, Iran, mothers, poverty, qualitative research

Introduction

Pregnant women who live in deprived area experience high risk of adverse outcomes due to lack of sufficient health and social care services. One of the best ways to support disadvantaged pregnant women is attendance of doulas beside them during childbearing to improve their outcomes.[1]

Women have experiences during childbirth that remain with them for the rest of their lives.[2] Research conducted in several countries indicates that the presence of a supportive person in the delivery room provides comfort to the mother, a pleasant experience throughout the childbirth process, and a reduced need for medical interventions. This supportive person maybe a midwife, husband, or someone with a close relationship to the expectant mother.[3] The presence of an attendant during childbirth has been reported to be associated with positive feelings and decreased anxiety among the mothers, and reductions in the number of caesarean sections and the duration of labor.[4] A study conducted in Iran on women's experiences with pain found that the optimal conditions for childbirth were a safe environment and the inclusion of multiparous women who shared their childbirth experiences.[5] A doula might also be someone who is trained in maternal-child care.[6] A recent study found that women who had more psychological support experienced greater satisfaction and were more engaged in decision-making about pain during normal deliveries compared with those in the control group.[7]

The presence of a trained or untrained individual during labor has recently become a status symbol in Iran. All mothers should be allowed and encouraged to be supported by someone when giving birth.[3] Although the presence of a doula in the delivery room is common in some private centers in Iran, it is less common in public facilities, which are used primarily by women opting for a low-cost, normal delivery. Failure to address this issue deprives women who are giving birth of the emotional support from relatives during this very stressful event. A reason for providing this kind of care is most likely related to the ignorance of the healthcare team about the real needs of expectant mothers, whereas research findings show that presence of an attendant or relative reduces the mother's anxiety and fear and increases her comfort during labor and delivery.[8,9] The evidence from Iran is that doulas may position themselves as advisers of “normal vaginal delivery and encouraging the mothers.”[10] A review of the relevant literature from Iran indicated that studies have not been conducted on the experiences and perceptions of expectant mothers regarding lay doula support. Thus, this study was designed to elicit and describe mothers' experiences with a lay doula during labor and delivery to gain a better understanding of them.

Materials and Methods

This qualitative study consisted of a structured interview and conventional methods of content analysis. According to Morse and Field, qualitative methods are used when little is known about the phenomenon being studied. This approach is useful to describe a phenomenon from the naive point of view.[11]

The participants consisted of women referring to the maternity units of facilities and hospitals affiliated with the University of Zahedan, Iran, who had their first normal vaginal birth and in the presence of an untrained doula at birth and 1 hour after birth, from August 2016 to April 2017. These centers render maternity care services to people who live in Cystan Baluchistan and have different active beds in labor room. A lay doula, who may be an untrained female friend or a relative and is selected by the mother-to-be, provides support and advocacy to expectant mothers.[10] Women with different levels of education and different ethnicities participated in the study, which was one of its strengths. Women who experienced any of the following childbirth-related conditions or complications were excluded from the study: placental abruption, premature rupture of the membranes, twin pregnancy, pre-term or post-term childbirth, accelerated or prolonged labor, preeclampsia, diabetes, induction, post-partum bleeding, prolapsed cord, and any situation in which there was fetal distress. Thirteen nulliparous women for this study were determined, based on data saturation. Participants were selected using purposive sampling and interviewed after they received a description of the study's goals and gave their written informed consent. The lay doulas were not ethnically diverse. They were selected by participants and ranged in age from early 35 to mid-40s. All had children of their own, and eight were grandmothers. Besides, they had not yet attended a birth.

The surveys, which involved face-to-face interviews, were conducted in participants' preferred environment after a suitable time was scheduled. At the beginning of the first interview session, interview guide and consent form were given to the participant to read, sign, and return to the researcher before the interview was initiated. The expected duration for each individual interview was approximately 60 min, which could be longer or shorter, depending on the length of the participant's responses to the questions.

Data were collected using a semi-structured interview, which began with the statement, “Please describe your experience with a doula.” Subsequent questions were asked to encourage the mother to share specific details (e.g., “What type of support did your doula provide?”). All the interviews were conducted in a quiet environment at a time determined by the mother, and they were audio-recorded and later transcribed. Two mothers chose the project base or their home, but others mother chose to be interviewed in postpartum room. The interview ended when the mother indicated that she had nothing more to say. The researcher carefully listened to the mother's responses and refrained from any form of interrogation.

Immediately following the interview, the author listened to the recorded dialog to determine whether the entire interview or parts of it needed to be repeated or clarified. Content analysis was conducted until data saturation was reached. Saturation occurs when no new content or information can be extracted from the data and when no new codes or themes can be added to the findings. When data saturation was achieved, two additional interviews were conducted to ensure that other possible findings were not overlooked during content analysis.[12,13] Sociodemographic information, including the mother's age, ethnicity, caste, educational level, and age at marriage, as well as her husband's age, educational level, and occupation were collected before the interview began.

Conventional content analysis was selected to examine the data collected in this qualitative study. This method, which is used for its subjective interpretation of textual data, allows codes and themes to be identified through systematic classification. Content analysis involves additional steps to objective content extraction from textual data. Using this method, implicit themes and patterns can also be manifested from the content of the participant's data.[11]

The interviews were audio-recorded with the participant's consent and then transcribed verbatim. Each interview was assigned a code and grouped with other codes based on the similarities and differences of the recorded information. The interviews were then classified and themes were extracted by grouping similar classes together. To ensure data validation, following data analysis, the transcribed content of the interviews and the primary codes that were extracted were given to the participants to review. The research team members had regular meetings and reviewed the process analysis; in addition, they passed the initial codes that came out from each interview to the concerned participants and they approved the emerged codes. Member-checks with the participants were conducted during the approval process. In addition, the extracted codes were shared with colleagues who were both involved and uninvolved in the research study to ensure rigor for data validation.

Ethical considerations

Approval to conduct this study was obtained before its implementation from the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (no. 6995). All participants signed an informed consent form, were made aware of the study's objectives, and were assured that their data would remain anonymous. They were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Results

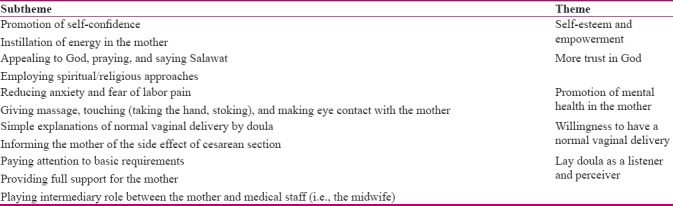

A total of 13 pregnant women who had been referred to childbirth centers or hospitals in Zahedan were interviewed. The mean age of the participants was 18 (22) years. Four of them had received a high school diploma, six had finished elementary school, and three were illiterate. All of them were nulliparous and all were homemakers. Participant's experiences were categorized into 11 subthemes and five major themes including the following: (1) achieving self-esteem and empowerment, (2) more trust in God, (3) promoting the mental health of the mother, (4) willingness toward normal childbirth, and (5) lay doula as a listener and perceiver [Table 1]. The mother's emotional and physical support from the doula continued through labor and after the delivery.

Table 1.

Main theme and subtheme of mothers’ experiences about having a doula during labor and delivery

Achieving self-esteem and empowerment

The mothers understood that their companion's role was as an active contributor who could provide her with a sense of power to overcome feelings of inadequacy.

Promoting self-confidence

A mother who had a positive experience with her companion said, “Thank God for allowing my companion to be here with me. Without my companion, I could not have … I feel as though I was giving birth with the help of my mom.” (Mother 7).

Another participant whose mother supported her noted, “After my delivery, my mom helped me to lactate. I thought I could not give milk to my baby, but I could. I just realized that to become a mother means becoming mature and high self-esteem. God bless you, I am so glad that my companion was with me.” (Mother 3).

Instilling energy in the mother

Another mother who received advice from her friend while giving birth recalled, “I was afraid of having a normal delivery from the beginning of my pregnancy. Nevertheless, when I was giving birth, my friend was with me and said, You were wrong. When you give birth, you forget about all the pain. You will feel it when you are giving milk to your baby.” (Mother 4).

She added, “Motherhood is a beautiful feeling that you will not understand it until you become a mother. These things gave me hope and good feelings. I would have lost my confidence if my companion had not been here. My mom was with me like an angel … she closed the door so that the sounds and screams of the other patients did not disturb me. I also tried to keep my headphones in my ears and listen to my favorite song, but when my pain increased, my companion helped me.”

One mother told, “my companion said to me: 'You are very strong … you are going to become a mother … you must be able to deal with problems from now on … you should think about raising your baby … you are not a child anymore … you are a mother'.” (Mother 7).

More trust in God

Another extracted theme was the faith of the mother and her companion in helping the mother to endure the pain and suffering of childbirth. Most of the mothers considered keeping a prayer on their stomach, leg, or neck, saying Salawat, and imploring God and the Imams to be effective in reducing their pain and fear, and to help them become calm. These beliefs were more prevalent in Baluchistan women.

Appealing to God, praying, and saying Salawat

A mother said, “Before coming to the hospital, my mom put a prayer on my leg … I think it was the effect of the prayer that made me calm and helped me give birth. Of course, my companion was already praying and blowing on my face.” (Mother 1).

Spiritual and religious approach

Another participant described her spiritual and religious approach as follows: “I think the prayers of my mommy, who was beside me, made me feel calm and less pain. My mom was with me and was constantly telling me to say Salawat for asking God to help me, especially at the end of my childbirth when my pain was worse and I had to scramble.” (Mother 12).

Another mother who shared her religious and spiritual views said, “We are a religious family. When my sister was beside me, she said that God gives us this pain to put Paradise under our legs … You know that the prophet's hadith says that heaven is under the mother's foot … I was so pleased with this, I tolerated the pain for God, and God helped me. I would die for my mom.”

“She always understands me. Now that my mom is beside me, I think that God is with me … My mom calms me down … and now I love her … I should never have hurt her … She used to tell me that she understood me and then she would hug me. Now that I hug my baby, I feel my mother better … She is love … She is God on the earth. I tolerated the pain for my mom and did not choose to have a caesarean.” (Mother 13).

Promoting the mental health of the mother

Most of the mothers believed that eye contact, touch, and massage by the companion provided a sense of calm and support during the different stages of childbirth. They said that these behaviors by the companion even facilitated a better relationship with medical staff. The time spent in the private room with a person with whom the mother had an emotional connection helped the mothers feel as if they were at home without fear or stress.

Reducing anxiety and fear of labor pain

A participant said, “When I had pain and my sister was beside me, I felt relaxed because someone who understood me was beside me and I could talk to her and forget my pain, which soon passed.” (Mother 5).

One of the mothers said, “My companion helped me overcome the fears I had because she was able to calm me down with a interaction and divert my attention, so that I could forget my pain. When she was not with me, every second passed like an hour.” (Mother 10).

Massage, touch (taking the hand, stoking), and eye contact with mother

Two mothers talked about the positive effects of being touched by others: “When I had pain, my mom's caresses were helpful.” (Mothers 2 and 3).

One of them recalled thinking about it: “I said to myself, 'I wanted my husband to be with me and hug me like my mom. Perhaps it was better that my husband was beside me and touched me'.” (Mother 2).

A second participant stated, “When I had pain, my sister was beside me and I felt brave because someone was beside me who understood me, so I could talk to her to forget my pain … Most of the time, the pain passed quickly and I was not scared.” (Mother 3).

One mother said, “My companion helped me to overcome my fears because she could calm me down by massaging my waist. She tried to divert my attention so that I would forget my pain momentarily. When she was not with me, every second passed as if it was an hour. If my companion had not been with me, I would have escaped from fear and anxiety, and no one would have taken me because I was going crazy due to the pain.” (Mother 6).

Willingness to normal vaginal delivery

The achievement of delivering a healthy baby led to a remarkable willing among the mothers toward normal childbirth.

Simple explanations of the normal vaginal delivery by doula who experienced vaginal birth

One participant stated, “I thought I would die if I had a normal childbirth because I was told that the pain of a normal delivery is the worst pain in the world … Although I saw the world flash in front of my eyes, I finally could handle it with the help and support of my mom … Every time my pain started, my mom took my hand and said: 'You can do it … you can do it …' A normal delivery is not as hard as you think … I gave you and your sisters birth via normal delivery … but I still did not believe this. I said, 'I am dying mom …' Now (after delivery) that I have given birth, I laugh at my thoughts and myself …” (Mother 8).

Informing the mother of the side effect of cesarean section

Another mother said, “A companion gives me more hope … At first I wanted a caesarean because I thought I would not be able to bear the pain. Is it possible that a child can exit the womb without tearing it?. My sister, who had three normal deliveries said, 'Yes, it is possible.' 'How do I give birth?'… 'You're my sister and you're going to make it'. Then I discovered that labor pain happens only at that time, and then it will be over, but now this woman next to me is infected at the site of the caesarean section and has pain. I wish she could have had a normal delivery.” (Mother 11).

Lay doula as a listener and perceiver

The mothers regarded their companion as a person who could understand them without -doing anything special and they provided continuous support throughout labor.

In her description of her companion's understanding, a mother said, “I did not expect anything special from my companion. Every time I screamed, she did not get angry. I knew that she understood me. I felt more comfortable with my companion. She helped me walk, took me to the toilet, and helped me take a shower.” (Mother 13).

Pays attention to basic needs

“I was more comfortable with my companion than with the personnel. She (companion) helped me walk, took me to the toilet, and helped me take a shower. It was a very nice feeling. I felt as though I was at home.” (Mothers 9 and 4).

Full support for the mother

Doulas provided continuous support throughout labor. One mother said, “My companion asked the midwife to give me a massage. My midwife came and massaged me and taught my companion how to massage me as well. When my mom massaged my waist my pain was reduced so much. My mom tried so hard; she massaged me all the time.” (Mother 5).

Intermediary between the mother and the medical staff (i.e., midwife)

Another mother said, “My companion was an intermediary between my midwife and me. When I was thirsty, my mom would ask her if she could give me water, and if the midwife let her, she would give me water.” (Mothers 2 and 10).

“My companion asked my midwife to give me a massage, and the midwife came and massaged me; then she taught my companion how to massage me as well. When my mom was massaging my waist, my pain was reduced. My mom tried so hard; she was massaging me all the time.” (Mothers 5 and 8).

Discussion

Five main themes were extracted using content analysis. Most of the mothers expressed satisfaction with the presence of a companion in the delivery room and believed that the support of their family (and perhaps their husband) helped to reduce their stress. Several factors were effective in contributing to the mother's development of empowerment including the companion's continuous presence in the delivery room, the mother's experience of closeness with others through their displays of affection (e.g., hugging her), and the companion's encouragement of the mother, especially during the second stage of childbirth in stilled energy and a sense of power in the mother. Several studies have found that the joy of being a mother and the sense of responsibility for a newborn baby increases a woman's confidence and strength.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]

In our study, one of the main themes was the mother's self-esteem and empowerment. The medical staff, the patient's companion, or maybe her husband could also have provided such support, which has been identified as an important and positive factor in the childbirth experience. This finding is consistent with the results of a previous study.[15] In other studies on mothers' views of childbirth and motherhood, the participants stated they felt valued because of their motherhood, which promoted their maturity and sense of responsibility. This feeling increased when the mother benefited from the support of her family or midwife during the birth process.[16] In many studies, trained individuals have served as companions; however, in this study, untrained persons assumed this role. This aspect of doula support has previously been highlighted by mothers in a study by Gentry and Hanley[17,18] Nonetheless, the results are similar, and perhaps, this is one of the strengths of this study. Therefore, it can be argued that if healthcare goal is to promote the optimal health of the mother and her baby, the use of untrained companions should be considered in all relevant planning and organizational policies.

The second extracted theme was “more trust in God.” Our results showed that spiritual and religious approaches were effective ways to deal with pain during labor. When prayers were kept on the mothers' legs or stomach, they felt protected by God and able to cope with the pain and fear of delivery. Several participants believed that their companion played an important role in their appeals to safe and reliable sources, such as Imams and God. This coping method increased their ability to bear the pain of labor and complete the birthing process without any complications. They felt no need for pain medication when they said Salawat. Other qualitative studies, which explored the experiences of mothers in pain during delivery, also found that trust in God was effective for women from different cultures and faiths (including Muslim women) during childbirth. Women who believed in divine providence had fewer fears and shorter delivery durations.[19,20,21]

Another theme obtained from participants' experiences was “Promoting the mental health of the mother.” Continuous psychological support is valuable during childbirth. The presence of a companion is associated with positive experiences, calmness of the mother, and improvement of the mother's mental health.[22,23] Our study's results are consistent with these studies. The participants believed that verbal and non-verbal gestures, such as skin contact with the companion, being massaged by her, listening to her conversations, and making eye contact without saying a word, reduced their fear and anxiety and made them feel as though time had passed more quickly.

In a qualitative study, the main theme was woman's fear of experiencing delivery alone, which included the subthemes of life-threatening risks, feelings of inadequacy, and complications.[20] Studies have found that mother's anxiety and fear have negative consequences for both her and her child. The presence of a companion during childbirth has physiological and psychological benefits, which increase the likelihood of a better delivery.[21,22] The participants in our study requested the presence of their spouses during labor. This request could not be met due to religious and Islamic beliefs that prohibit the presence of a husband at the patient's bedside. In accordance with the relevant laws of poorer communities with a religious context (i.e., Shia and Sunni), scholars believe that the presence of a spouse during childbirth is not permitted by restricted rules of hospitals, and mothers should only choose a woman as a companion (i.e., someone with a continuous presence who can assist the mother with all aspects of personal care).

According to some studies, common barriers to male involvement included lack of men's maternal health and gendered divisions of cultural responsibilities, and health structures. It is important that the barriers identified in this and other studies are addressed in future intervention design and implementation.[23,24] Perhaps this is a study limitation that was beyond the control of the researcher.

The fourth extracted theme was “willingness to normal vaginal delivery.” Our study showed that simple explanations about normal deliveries and complications of caesarean sections given by companions who had this type of delivery, and further explanations by a midwife, increased mothers' familiarity with the risks of deliveries by caesarean sections which have increased in Iran.[25] The mothers' misconceptions about normal birthing process were corrected and there was a positive change in their willing about this type of delivery.[26] Studies have found that the first birth experience is of critical importance in mothers' preference for the type of delivery desired in the future.[27] Nevertheless, the results showed the presence of a companion led to reduced fear and anxiety in the mother, and in most cases, it reduced the duration of the labor and delivery stages of the birth. Reducing the mother's fear and anxiety was effective in improving both her mental health and their willing to give birth through natural delivery. The results from other studies showed that forming an intimate relationship by establishing trust during labor can turn off the cycle of fear, stress, and pain, and it is associated with decreased catecholamine.[28,29]

The last theme obtained in this study was “lay doula as a listener and perceiver.” This study explored how doulas help mothers adapt to changes in circumstances of labor and birth from mothers' idealized birth plan. The mothers in this study believed their relative provided many benefits, such as helping them walk around the labor room, bringing water to them, and, as several pointed out, the companion served as a mediator between them and healthcare professionals (i.e., midwives and doctors). Although several studies have highlighted the significance of the presence of mother's partner or another trusted person during labor,[30,31,32] healthcare providers, especially in poverty-stricken areas of Iran, have ignored this important service. Giving non-judgmental support, assisting with informed decision-making, and acting as a facilitator are cornerstones of doula care and strongly express the shared values of doulas. Many mothers described how they valued the contribution of their doulas in communicating with other staff within hospital setting.

There were some limitations that are common in many qualitative studies such as small sample size and limitation in mothers' memory in verbalizing experiences. Finally, midwives were not participants in the study and mothers were not allowed to choose their husbands as their lay doula due to restrictive hospital rule.

Within the scope of doula research, this study highlighted that it is time to include the perspective of support persons (such as husbands) and maternity health professionals in research design of future studies.

Conclusion

This qualitative study is the first of its kind in Iran to explore the support given to expectant mother through the presence of a family member or friend during labor and delivery stage of childbirth. Doulas can play an important role in improving women's birth experience in deprived area by providing mental and emotional support, encouraging mother to give normal birth and full support of disadvantaged women. The mothers suggested making arrangement so their husbands could be at their bedside or so their next delivery could be at their home with a untrained companion present during childbirth process. Based on the findings of this study, the quality of maternity service should be measured and healthcare professional must be cognizant of the need, value, beliefs, preference, and emotional well-being of disadvantaged women.

Financial support and sponsorship

Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran

Conflicts of interest

Nothing to declare.

Acknowledgement

The authors appreciate and thank the midwives and the mothers admitted to the hospitals and maternity members in the centers, covered by the university, who expressed their valuable experiences.

References

- 1.Spiby H, Green JM, Darwin Z, Willmot H, Knox D, McLeish J, Smith M. Multisite implementation of trained volunteer doula support for disadvantaged childbearing women: A mixed-methods evaluation. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2015;3:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundgren I. Swedish women's experiences of doula support during childbirth. Midwifery. 2010;26:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C, Weston J. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2012;2:37–66. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenneth J, Gruber KJ, Cupito SH, Dobson CF. Impact of doulas on healthy birth outcomes. 2013;22:49–58. doi: 10.1891/1058-1243.22.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahoei R, Khosravy F, Zaheri F, Hasheminasab L, Ranaei F, Hesame K, et al. Iranian Kurdish women's experiences of childbirth qualitative study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19:112–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vonderheid SC, Kishi R, Norr KF, Klima C. Group prenatal care and doula care for pregnant women. In: Handler A, Kennelly J, Peacock N, editors. Reducing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Reproductive and Perinatal Outcomes: The Evidence from Population-Based Interventions. New York: Springer eBooks; 2011. pp. 369–99. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jafari E, Mohebbi P, Mazloomzadeh S. Factors related to women's childbirth satisfaction in physiologic and routine childbirth groups. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2017;22:219–24. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.208161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chor J, Hill B, Martins S, Mistretta S, Patel A, Gilliam M. Doula support during first-trimester surgical abortion: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 2015;212:1–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King TL, Pinger W. Evidence-based practice for intra partum care: The pearls of midwifery. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2014;59:572–585. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safarzadeh A, Beigi M, Salehian T, Khojasteh F, Burayri T. Effect of doula support on labor pain and outcomes in primiparous women in Zahedan, southeastern Iran: A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Relief. 2012;1:100–12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Streubert H, Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nursing; advancing the humanistic imperative. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. pp. 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holloway I, Wheeler S. Qualitative research in nursing and health care. John Wiley & Sons. 2010 ISBN: 978-1-119-09636-8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fathi Najafi T, Latifnejad Roudsari R, Ebrahimipour H. The best encouraging persons in labor: A content analysis of Iranian mothers' experiences of labor support. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darwin Z, Green J, McLeish J, Willmot H, Spiby H. Evaluation of trained volunteer doula services for disadvantaged women in five areas in England: Women's experiences. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:466–77. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell-Voytal K, Fry McComish J, Visger JM, Rowland CA, Kelleher J. Postpartum doulas: Motivations and perceptions of practice. Midwifery. 2011;27:214–21. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gentry QM, Nolte KM, Gonzalez A, Pearson M, Ivey S. “Going beyond the call of doula”: A grounded theory analysis of the diverse roles community-based doulas play in the lives of pregnant and parenting adolescent mothers. J Prenat Educ. 2010;19:24–40. doi: 10.1624/105812410X530910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanley GE, Lee L. An economic model of professional doula support in labor in British Columbia, Canada. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62:607–13. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boryri T, Noori NM, Teimouri A, Yaghobinia F. The perception of primiparous mothers of comfortable resources in labor pain (a qualitative study) Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2016;21:239–46. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.180386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arfaie K, Nahidi F, Simbar M, Bakhtiari M. The role of fear of childbirth in pregnancy related anxiety in Iranian women: A qualitative research. Electron Physician. 2017;9:3733–40. doi: 10.19082/3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahlen HG, Barclay LM, Homer CSE. The novice birthing: Theorizing first- time mother's experiences of birth at home and in hospital in Australia. Midwifery. 2010;26:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theuring S, Mbezi P, Luvanda H, Jordan-Harder B, Kunz A, Harms G. Male involvement in PMTCT services in Mbeya Region, Tanzania. AIDS Behave. 2009;13:92–102. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9543-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reece M, Hollub A, Nangami M, Lane K. Assessing male spousal engagement with prevention of mother-to-child (pMTCT) programs in western Kenya. AIDS Care. 2010;22:743–50. doi: 10.1080/09540120903431330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ministry of Health and Medical Education Ministry of Health and Medical Education Performance in the eleven governments, Annual Report. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Supporting Healthy and Normal Physiologic Childbirth: A Consensus Statement by ACNM, MANA, and NACPM. Prenat Educ. 2013;22:14–8. doi: 10.1891/1058-1243.22.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennel J, Klaus M, McGrath S, Robertson S, Hinckley C. Continuous emotional support during labor in a US hospital. J Am Med Assoc. 1991;265:2197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alehagen S, Wijma B, Lundberg U, Wijma K. Fear, pain and stress hormones during childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;26:153–65. doi: 10.1080/01443610400023072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burman ME, Robinson B, Hart AM. Linking evidence-based nursing practice and patient-centered care through patient preferences. Nurs Adm Q. 2013;37:231–41. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e318295ed6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corry MP, Jolivet R. Doing the right thing for women and babies: Policy initiatives to improve maternity care quality and value. J Perinat Educ. 2009;18:7–11. doi: 10.1624/105812409X396183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karlström A, Nystedt A, Hildingsson I. The meaning of a very positive birth experience: Focus groups discussions with women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:251. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0683-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyndon A, Zlatnik MG, Wachter RM. Effective physician-nurse communication: A patient safety essential for labor & delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]