Abstract

Continuous dopaminergic stimulation (CDS) has become one of the main concepts in present Parkinson's disease (PD) research. This is based on the assumption that CDS, or rather near CDS, is the normal striatal setting in a healthy individual. In PD, the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons leads to a reduced capacity to buffer dopamine, which could increase the vulnerability to a pulsatile administration of drugs. The term continuous drug delivery (CDD) describes the process of delivering drugs continuously with the aim of achieving CDS. There are three principal techniques for non‐oral CDD: continuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusion CSAi), levodopa‐carbidopa intestinal gel infusion (LCIGi), and transdermal rotigotine therapy. CDD has repeatedly been shown effective in the day‐to‐day treatment of PD patients. Although this review does not replace local guidelines regarding the use of the included non‐oral CDD‐based therapies, we have compiled the current base of evidence or consensus view with the intention of facilitating both the selection and the use in a clinical setting. The indications for CSAi and LCIGi are very similar and are centered around motor complications in advanced PD, whereas rotigotine has been proven effective both as a monotherapy in early PD and as an add‐on to levodopa in advanced PD. Deep‐brain stimulation is a relevant option for many of the patients with advanced PD, and we therefore also discuss its use in relation to the CDD‐based techniques. Blinded and controlled trials have shown that non‐oral CDD is an effective approach for the treatment of PD.

Keywords: antiparkinson agents/administration and dosage, drug delivery systems, infusion pumps, Parkinson's disease, review

Introduction

Although Parkinson's disease (PD) often can be treated effectively at an early stage, both motor and non‐motor complications become significant with time. The continuous dopaminergic stimulation (CDS) hypothesis has gradually become one of the primary theoretical underpinnings for development in the PD field, and it constitutes an example of how the integration of basic and clinical research can lead to improved patient outcomes in clinical practice.1

CDS and Complications of Parkinson's Disease

The term CDS refers to the continuous stimulation of postsynaptic neurons, which is postulated to resemble the tonic firing of striatal neurons in individuals without PD.1, 2, 3 When a movement is initiated and the firing of striatal neurons becomes phasic, there is normally enough buffered dopamine to activate the postsynaptic terminal. As PD progresses, the presynapses degenerate and the ability to buffer dopamine is reduced.2, 3 This contributes to the rise of “off”‐fluctuations, in which patients experience periods of “off” between doses. These “off”‐fluctuations also occur in patients treated with dopamine agonists (DAs), which, in contrast to dopamine, are not buffered presynaptically. Hence there is likely to be a postsynaptic contribution to the origin of “off”‐fluctuations as well.2, 3

Studies suggest that there are dose‐dependent relationships between levodopa (l‐dopa) and both dyskinesia and “off”‐fluctuations.4, 5 The plasma levels of a drug do not correspond directly to the amount of active substance available at the synaptic level, but PD patients with motor complications exhibit nonphysiological levels of striatal dopamine,6 possibly as a result of an increased vulnerability to fluctuating plasma levels of l‐dopa. “Off”‐fluctuations during oral l‐dopa therapy might also relate to the short half‐life of l‐dopa and the fact that oral l‐dopa treatment is dependent on the passage through the stomach before uptake—a passage that is often complicated by delayed gastric emptying and gastroparesis.7

Non‐motor symptoms are often more prominent when patients are in motor “off” than in “on,” but there are exceptions that occur in both states or only during “on.”8 Non‐motor complications are likely to be of a heterogeneous origin; some are a direct result of dopaminergic dysfunction and others are an effect of dysregulated interactions between dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons.3 Other symptoms, for example hallucinations/psychosis or impulse control disorders (ICD), are likely in part iatrogenic and are induced by stress on an already dysregulated dopamine system.

CDS Versus CDD

It is complicated to quantify the level of CDS that a certain therapy achieves in a patient. This makes the term “CDS” inaccurate when discussing therapeutic options in a clinical setting. Instead, the closely related term “continuous drug delivery” (CDD) is sometimes used to describe the more hands‐on concept of delivering drugs continuously with the aim of achieving CDS. As all aspects of CDS are not fully understood, it is thus reasonable instead to focus on CDD in the day‐to‐day treatment of PD patients.2

Review Aims—An Update on “Which Non‐oral CDD Suits Which Patient?”

The process for recommending a certain CDD technique to a specific patient is often a matter of local preference, and further clarification is needed. A multinational working group has compiled an evidence‐based review of the selection between two non‐oral CDD techniques and deep‐brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nuclei for patients with advanced PD and motor complications.9 Although that review is both rigorous and useful, several important findings have been published since its compilation. Our aim with this review is to provide an update describing which non‐oral CDD technique to use for various patients and to answer questions on how and when to use it.

Therapies Included in the Review

We describe three non‐oral techniques for CDD: continuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusion (CSAi), levodopa‐carbidopa intestinal gel infusion (LCIGi), and rotigotine therapy.

Apomorphine is a non‐ergot DA and was introduced as a treatment for PD during the second half of the 20th century. The experience with the drug, both as single injections and as a CSAi, is long.10 CSAi is administered with the help of a battery‐driven pump that infuses the drug subcutaneously, mostly on the lower part of the abdomen or on a thigh. The patient carries the injection pump in a pocket or a small pouch.

The suspension used for LCIGi is an aqueous carboxymethylcellulose gel containing 20 mg/mL l‐dopa and 5 mg/mL of the dopa decarboxylase inhibitor carbidopa. The gel is packaged in cassettes that are loaded into a battery‐driven infusion pump that can be carried in a belt, for instance around the waist or over the shoulder. The pump continuously administers the gel through a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with a jejunal tube (PEG‐J) into the upper part of the small intestine.

Rotigotine is a non‐ergot DA that is formulated as a transdermal system. The rotigotine is embedded in a patch that is applied once daily on the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm. The drug is then administered evenly and continuously throughout the day. The next day, the patch is removed and a new patch is applied to a new site. Several formulations of rotigotine have been on the market, and a formulation that is stable in room temperature was approved in 2012.11

The indications for CSAi and LCIGi are very similar: severe PD, pronounced motor fluctuations, dyskinesias, and nocturnal akinesia. Rotigotine is suggested as a monotherapy in early PD and as an add‐on to l‐dopa in patients with advanced PD. Although DBS is not part of the primary focus of this review, DBS is inevitably included also in the discussion on the choice of a non‐oral CDD technique that is suitable for a certain patient. DBS is a safe and efficacious therapy for patients with advanced PD and is in a clinical setting relevant option for many of the patients that are considered for CSAi or LCIGi and vice versa.

Methods

We used two elaborate reviews as the foundation for a new database search performed in June 2015: (1) an evidence‐based review by a multinational working group concerning CSAi and LCIGi9; and (2) a systematic review and meta‐analysis on rotigotine.12 We searched for publications after the reported last search date for an update of the literature for both articles: May 2012 for CSAi and LCIGi, and July 2012 for rotigotine. We searched the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases for variations of the terms “rotigotine,” “levodopa infusion,” and “apomorphine” in combination with “Parkinson disease.” Many practical aspects of PD therapy are not strictly evidence based, and to increase the reliability of these matters in this review, we have used a consensus report on non‐oral medication, Navigate PD,13 in cases for which evidence‐based data are lacking. Navigate PD is a consensus statement based on the experience of more than 100 movement disorder specialists.

As the evidence strength of the published studies varied between the included therapies, we included all original studies with clinical data on CSAi; randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled trials, and open‐label trials including ≥40 patients on LCIGi; and RCTs and meta‐analyses of RCTs on rotigotine. In addition to the three initial reviews, we also included the six studies from the meta‐analysis on rotigotine, as more material on non‐motor aspects of the therapy was needed. Twenty‐one articles were identified during the literature search: three on CSAi #bib11 on LCIGi, and seven on rotigotine. All in all, we included a total of 30 articles.

The literature search was performed by J.T. and was verified by T.H. and P.O. The articles were grouped by CDD technique and then were summarized regarding efficacy, side effects, contraindications, and “for whom, when, and how?” categories. The summaries of the evidence for each technique were used to outline recommendations for therapy selection.

Results

Following the presentation of the non‐oral CDD therapies, we provide a rundown of the selection between non‐oral CDD therapies and DBS.

CSAi

Motor Symptoms

The knowledge regarding CSAi and its effects is currently based on a number of small, open‐label studies. The primary effect of CSAi seems to be a reduction of time spent in “off.” CSAi reduces the time spent in off at a median of 44%, and, although the evidence base for this is weak, it increases the duration spent in or without dyskinesia at a median of 40%.9 The impact of CSAi on dyskinesia varies between studies, but two studies have focused on CSAi and its effect on dyskinesia and they present a beneficial effect on dyskinesia‐related outcomes.9 This improvement seems larger in patients who rely mostly on CSAi and who use either no concurrent oral l‐dopa or only low doses of concurrent oral l‐dopa. When CSAi doses are kept low and the oral medications are not discontinued, dyskinesia seems to improve less.14 Patients on CSAi typically exhibit significant improvements on the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), parts III and IV, during open‐label study,15, 16 but also show improvements in activities of daily living (ADL) function as measured on the UPDRS II.14

Non‐motor Symptoms

In an open‐label study of 43 patients with CSAi, both the mean total score on the Non‐Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS) and the mean score on the NMSS domains sleep/fatigue, mood/apathy, perceptual/hallucinations, attention/memory, gastrointestinal, and urinary were significantly improved at the 6‐month follow‐up.16 In the same study, the outcomes for patients with CSAi were compared to the outcomes for 44 patients with LCIGi. Improvements on the NMSS domains sleep/fatigue, gastrointestinal, urinary, and sexual functioning were significantly larger for patients with LCIGi, but there was also a statistically nonsignificant tendency for a better effect on mood/apathy in patients with CSAi. A small study on patients with CSAi during the day and rotigotine during the night showed a significant improvement in NMSS total score at a 2‐year follow‐up.15

CSAi is often administered only during the waking day, which is based on the clinical experience that this timing may reduce the side effects of the therapy in comparison to around‐the‐clock infusion.9

Health‐Related Quality of Life

According to one study, patient health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) improves significantly after 6 months of CSAi.16 However, another study showed no significant improvements of HRQoL after initiation of CSAi, possibly because of the fact that patients were still relying on oral medication to a large degree.14

Other Relevant Factors

Studies generally fail to present adverse events (AEs) in relation to patient age, but a positive effect of CSAi is seen at least up to the age of 85 years. Long disease duration does not seem to reduce the positive effects of CSAi. There are indications that CSAi includes a beneficial effect on gait, possibly directly related to the reduction of side effects with a linkage to the oral l‐dopa intake, for example, dyskinesias.9

Precautions or Contraindications

Severe dementia, a lack of l‐dopa response, and an inability to handle the device are contraindications to CSAi. CSAi is also to be avoided in patients with low compliance to noninvasive therapies, and it is advisable to consider the use of some other therapeutic approach than CSAi for patients with hallucinations or ICD.9 Because of the high incidence of skin‐related complications, CSAi may be unsuitable for patients with an ongoing skin condition or comorbidity that increases the risk for infection, for example, diabetes mellitus. The clinical experience is that the incidence of skin reactions can be reduced through frequent changes of infusion site, a “dry” application technique (no apomorphine in the needle during application), dilution of the drug, application of silicone gel dressings, a change from steel to Teflon needle, and ultrasound treatment or massage of the infusion site.10

CSAi: For Whom, When, and How?

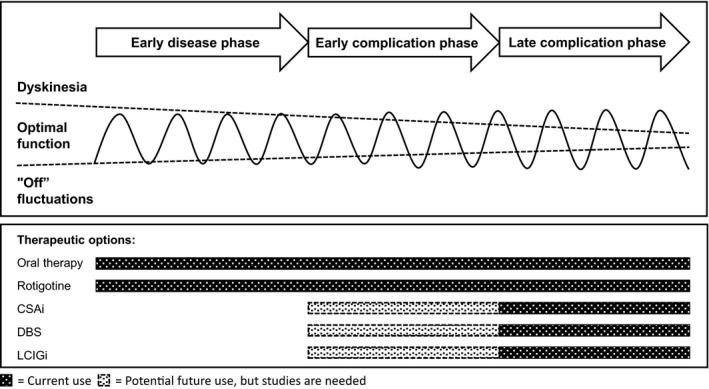

The evidence base for CSAi is poor, but the clinical experience is substantial, and CSAi has repeatedly been shown to result in significant improvements in patients with advanced PD during open‐label study (Box 1). CSAi should be considered for patients with advanced PD in whom oral therapy no longer prevents the patient from experiencing significant periods in “off” or when the needed number of rescue doses of apomorphine injections exceed about four to six per day. CSAi is also less invasive than both DBS and LCIGi and is entirely reversible. CSAi is also an option for patients with a biological age older than 70 to 75 years; an age group in which DBS seems less suitable.9 CSAi should be used with caution in patients with previous drug‐related hallucinations or ICD, and both LCIGi and DBS could be regarded as more suitable in these cases. There are no studies that define the optimal stage for initiation of CSAi, but the effect is hypothesized to be better early in the complication phase rather than late (Fig. 1).

Box 1. Advantages of CSAi.

Improves motor and non‐motor symptoms.

The least invasive device‐aided therapy.

Entirely reversible.

No upper age limit.

An option for patients with slight to moderate dementia.

Figure 1.

The use of different therapeutic techniques in Parkinson's disease. The curve is a stylized representation of the clinical responses at different stages of Parkinson's disease. CSAi, continuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusion; DBS, deep‐brain stimulation; LCIGi, l‐dopa‐carbidopa intestinal gel infusion.

Patients who are initiating CSAi are to undergo an examination including an ECG (for control of QT duration) and blood tests (for exclusion of hemolytic anemia). The risk for developing hemolytic anemia is present throughout the treatment. Therefore, the hemoglobin level should be measured at least twice a year. Patients may be given domperidone to reduce nausea and vomiting during the starting phase of CSAi, which may begin 1 to 3 days before the initiation of treatment and continue up to a few weeks.13 The European Medicines Agency recently lowered the maximum recommended dose of domperidone to 10 mg three times daily to reduce the risk of QT interval prolongation and arrhythmias.

There are several ways to initiate CSAi, and the oral medication is handled differently among methods. Some centers have developed outpatient models for initiation of CSAi, but inpatient initiation is still more common. CSAi treatment is sometimes initiated with an apomorphine test, which may increase compliance as patients obtain a better understanding of the treatment efficacy and side effects. Regardless of the method used, the goal is generally to reduce the l‐dopa dose by at least 50% and to discontinue all other anti‐parkinsonian medications; however, the speed at which this happens differs.

The total daily dose of CSAi consists of three doses: a morning dose, a maintenance dose, and—if needed—extra bolus doses. The CSAi starting dose can either be calculated from the previous medication using the l‐dopa equivalence dose, or it can be started low and then be increased with 0.5 to 1 mg/hr until the maintenance dose is reached, usually around 4 to 7 mg/hr. The CSAi is removed before bedtime, and a long‐acting DA or a slow‐release l‐dopa dose can be administered to reduce nighttime symptoms.15 As CSAi seems to be particularly effective when it is used as a daytime monotherapy, the goal should be to try this for most patients at some point during treatment. However, the majority of patients do need additional l‐dopa in parallel with the CSAi for an optimal effect. Normally, patients spend between 1 and 2 weeks in‐ward during the initiation of the CSAi, which is enough time to adjust the infusion and oral medications, but is also enough time for the patient and/or caregiver to learn to handle the infusion pump.

LCIGi

Motor Symptoms

In the 12‐week RCT on LCIGi, patients allocated to LCIGi exhibited a reduction in mean time per day spent in “off” with 4.0 hours (−64%), which was 1.9 hours more than patients allocated to oral l‐dopa.17 Furthermore, the patients with LCIGi increased the mean time spent in “on without troublesome dyskinesia” with 4.1 hours (+65%), which was 1.9 hours more than their counterparts allocated to oral l‐dopa. The mean “off” duration has also been reported as significantly reduced with LCIGi during open‐label study,9, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 with the decrease typically ranging from 40% to 80%.9 LCIGi is reported to have a beneficial effect on dyskinesia.18, 20, 22 One open‐label study suggests that LCIGi reduces the duration of troublesome dyskinesia for patients with longer dyskinesia durations at baseline, but that the duration with nontroublesome dyskinesia increases for patients who have shorter dyskinesia durations at baseline.23

LCIGi results in mean improvements of motor function as measured on the UPDRS, and most studies present significant improvements of total score and/or subscores on parts II, III, or IV.16, 18, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25 The reduced time with dyskinesia is not thought related to the total daily l‐dopa dose, but rather to the CDD.9 The reported improvements on UPDRS III are measured in “on” and suggest a higher quality “on” period with LCIGi than with the baseline medication, but this finding was not supported by the RCT.17

Non‐motor Symptoms

LCIGi leads to significant improvements of non‐motor symptoms as measured on the NMSS, but thus far these only were evident during open‐label studies.9, 16, 20, 25 The NMSS domains sleep/fatigue, gastrointestinal, and urinary are typically among the domains that exhibit the most notable improvements from LCIGi, both in comparison to other NMSS domains and in comparison to CSAi.9, 16, 20

There is some evidence that LCIGi includes a beneficial impact on neuropsychiatric symptoms, which is likely an effect of the transition from polypharmacy to few drugs or even to monotherapy.9 The clinical experience for some patients is that a switch from oral therapy to LCIGi improves symptoms such as ICD, hallucinations, anxiety, and depression.9, 13

Health‐Related Quality of Life

LCIGi leads to mean improvements in patients' HRQoL. The improvement compared to baseline is present from the first day of treatment to 4 weeks after initiation of LCIGi.18, 20 The effect is then sustained until the last follow‐up at 6 to 12 months from baseline.16, 18, 20, 25 One study presents a significant improvement from the mean 8‐item Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ‐8) total score at baseline, but the durations until the last visits for the patients in question are not presented.22

Other Relevant Factors

A large portion of the AEs related to LCIGi are associated with the PEG‐J and occur in the period directly following the placement of the PEG‐J. An established cooperation with experienced gastroenterologists might contribute to reducing these complications. The structure for presentation of AEs differs among studies, which makes comparison difficult, but studies generally report procedure‐ or device‐related AEs in 28% to 92% of patients.13, 17, 18, 22 Common AEs include abdominal pain, wound infection, and nausea, and all of these are seen in about 10% to 50% of patients.13, 17, 18, 20 Displacement of the tube is commonplace but can be handled. LCIGi is also associated with an increased incidence of polyneuropathy, but it has not been made entirely clear whether this is related specifically to LCIGi, to l‐dopa treatment in general, or even to PD itself. Weight loss was reported in 15.4% of patients in the largest open‐label study,18 but there is currently little evidence for a link between LCIGi and malabsorption.

Precautions or Contraindications

Severe dementia, a lack of l‐dopa response, and an inability to handle the device are contraindications for LCIGi. When filled, the infusion pump used for LCIGi weighs about 500 grams. The weight is perceived as a problem by some patients and could be considered a relative contraindication for the frailest patients.9 This is also a possible explanation for the somewhat higher drop‐out rate among women.26 Medical conditions that prohibit the installation of the PEG‐J are contraindications for LCIGi, for example, significant adherences resulting from previous abdominal surgeries.

LCIGi: For Whom, When, and How?

LCIGi is a valid option for most patients who are considered for DBS and for many of the patients for whom DBS is contraindicated. LCIGi is also efficacious in older PD patients and remains an option for patients with slight to moderate dementia but sufficient support from a caregiver (Box 2).13 LCIGi may be problematic for patients with pronounced dementia, especially when there is a risk for manipulation of the infusion pump or tubing. It has been hypothesized that LCIGi would be even more beneficial to some patients if it were initiated at an earlier stage than what has been common practice, but the evidence for this is weak (Fig. 1).

Box 2. Advantages of LCIGi.

Improves motor and non‐motor symptoms.

The effects on motor symptoms have been verified in a randomized controlled trial.

No upper age limit.

An option for patients with slight to moderate dementia.

Possible monotherapy.

The response to LCIGi may be evaluated during a nasoduodenal testing phase, which is especially valuable in patients with weaker indications and reduces the risk of introducing a PEG‐J in patients with unsatisfying responses to the therapy. This extra step may increase the compliance, as both patient and caregiver obtain a better idea of how the treatment works. The modes of the procedure differ among centers, and the nasoduodenal phase is often skipped, particularly for patients with a clear indication. The PEG‐J needed for LCIGi is placed under short‐acting general anesthesia.

The total daily dose of LCIGi consists of three doses: a morning dose, a maintenance dose, and extra bolus doses if required. The starting LCIGi morning dose is based on the patient's oral morning dose and is usually 5 to 10 mL. The starting maintenance dose is based on the l‐dopa equivalence dose of the discontinued medication and is titrated in steps of 0.1 to 0.2 mL/hr until an optimal response is reached. The bolus doses are 0.5 to 2 mL and the patient can self‐administer when needed. If many bolus doses are required, the maintenance dose should be increased.

The aim often is to use LCIGi as a monotherapy, but some patients are on a combination of LCIGi and low doses of DAs or amantadine. The LCIGi is administered either as a 16‐hour infusion or as a round‐the‐clock infusion with, for instance, a 30% lower maintenance dose by night. In the included studies, LCIGi is mostly administered as a daytime infusion. Slow‐release l‐dopa or long‐acting DAs can be used in the evening to reduce nighttime symptoms for patients with daytime LCIGi.13

There have been attempts to perform the early titration of LCIGi in an outpatient setting, but the inpatient model is still regarded as the established clinical practice. In patients in whom signs of polyneuropathy occur, the symptoms might improve from supplementation of vitamin B12 or folic acid. There is no consensus regarding the handling of polyneuropathy during LCIGi, but it is recommended routinely to control serum‐levels and/or to substitute vitamin B12 and folic acid before and after initiation of LCIGi.13 It is reasonable to do this with shorter intervals during the first year and from then on during yearly controls. In cases in which the polyneuropathy is progressive and is not improved by supplementation of vitamin B12 or folic acid, discontinuation of the LCIGi should be considered.

Rotigotine

Motor Symptoms

Rotigotine has repeatedly been shown to improve ADL and motor function as measured on the UPDRS part II and/or III in patients with either early or advanced PD when compared to the placebo control group12, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 Rotigotine also reduces “off” time significantly as an add‐on to l‐dopa in patients with mid‐ to advanced‐stage PD.29, 34, 35, 37 One study showed that rotigotine doses ≤8 mg/24 hr did not reach noninferiority to ropinirole doses ≤24 mg/24 hr, but were instead similar to the efficacy of ropinirole doses ≤12 mg/24 hr.33 This was supported by a study that showed that ≤16 mg/24 hr rotigotine was noninferior to ≤15 mg/24 hr ropinirole in its effect on UPDRS II and III and on changes in “on” and “off” duration.29 One study indicated noninferiority to pramipexole in the reduction of time in “off.”34 Some studies suggested an increased occurrence of dyskinesias in patients with rotigotine compared to placebo controls.29, 34, 37

The studies mainly focus on the use of rotigotine as a monotherapy in early PD and as an add‐on in mid‐stage to advanced PD. However, when rotigotine monotherapy no longer has the desired effect, the clinical practice is often to use rotigotine simultaneously with l‐dopa also at a relatively early stage of PD. This approach aims to reduce the early l‐dopa use, but the early combination therapy's effect on disease complications is not entirely clear.

Non‐motor Symptoms

One study showed 4 weeks of maintenance treatment with rotigotine as superior to placebo on both the effect on sleep quality and nocturnal disabilities—as measured on a modified version of the Parkinson's Disease Sleep Scale (PDSS‐2)—and other non‐motor symptoms, particularly on the NMSS domains sleep/fatigue and mood/cognition.36 The effect on the PDSS‐2 was also noninferior to ropinirole in a 16‐week trial.29

DAs are commonly reported to increase the risk for induction or exacerbation of several neuropsychiatric symptoms, particularly ICD and psychotic symptoms. Hence, signs of these should be evaluated whenever the patient visits the outpatient clinic.

Health‐Related Quality of Life

Six months of rotigotine therapy led to significant improvements of HRQoL as measured on the 39‐item PDQ (PDQ‐39) in patients with “wearing off” and at least 2.5 hr/day in “off” at baseline.34 Another study used PDQ‐8, but showed a similar significant improvement after 4 weeks of treatment with rotigotine compared to placebo in a population of patients with early‐morning motor symptoms.36 A third study showed a small improvement of HRQoL in the rotigotine group compared to baseline, but the improvement was not statistically significant.31

Other Relevant Factors

Application site reactions are by far the most common AE seen during rotigotine therapy and might occur as often as in 30% to 60% of all patients.27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 35, 38 In some patients, the patch has a tendency to fall off. Early PD patients on rotigotine are at a higher risk of vomiting and nausea compared to placebo controls.12, 30, 31, 32, 38 In the meta‐analyses, there is no evidence that rotigotine increases the risk for constipation,12, 38 which was suggested recently.27

Precautions or Contraindications

As DAs could induce or exacerbate hallucinations or psychotic symptoms, rotigotine may not be suitable for patients with previous psychosis. In a few patients, the skin does not tolerate the patch. Due to a possible effect on blood pressure regulation and orthostatic hypotension, other therapeutic options should be considered in cases with pre‐existing cardiovascular disease. The rotigotine patch contains aluminum and must be removed during magnetic resonance imaging or electric cardioversion.

Rotigotine: For Whom, When, and How?

Rotigotine is efficacious both as a monotherapy in early PD and as an add‐on to l‐dopa in patients with advanced PD (Fig. 1 and Box 3). Any superiority of rotigotine to oral DAs has not been proven, but there has been a report of effects on non‐motor symptoms that might be unique to rotigotine.36 However, it needs to be clarified whether this claim holds also in direct comparison with oral DAs—rather than placebo—and whether the improvements are caused by a direct effect on non‐motor symptoms or if they are the result of an improved motor function. Rotigotine is an option in the treatment of problematic early‐morning motor symptoms, nocturnal disability, or insomnia, but also for perioperative use and for patients with dysphagia or low compliance to oral medications.

Box 3. Advantages of Rotigotine.

Improves motor and non‐motor symptoms in randomized controlled trials.

No upper age limit.

Improves early morning motor symptoms.

Remains effective for patients with delayed gastric emptying or difficulties swallowing.

May increase compliance in patients with low compliance to oral medications.

In the available studies on PD patients, rotigotine is generally well tolerated across all age groups, but, like other DAs, it is reasonable to consider some other therapeutic approach in patients with preexisting psychotic symptoms. The recommended entry doses of rotigotine are 2 mg/24 hr in early and 4 mg/24 hr in advanced PD. Doses may then be increased by 2 mg/24 hr/week up to a maximum dose of 8 mg/24 hr in early and 16 mg/24 hr in advanced PD.39

Recommendations for the Selection Between Non‐oral CDD and DBS

Rotigotine is also used in advanced PD, but the efficacy is not in line with that of the device‐aided therapies. Balanced and personalized information on the device‐aided therapy options is to be provided to the patient at a relatively early stage, especially so for young‐onset patients.13 The physician has a key role in this process, but it is important to encourage the patient to contact one of the PD patient associations.

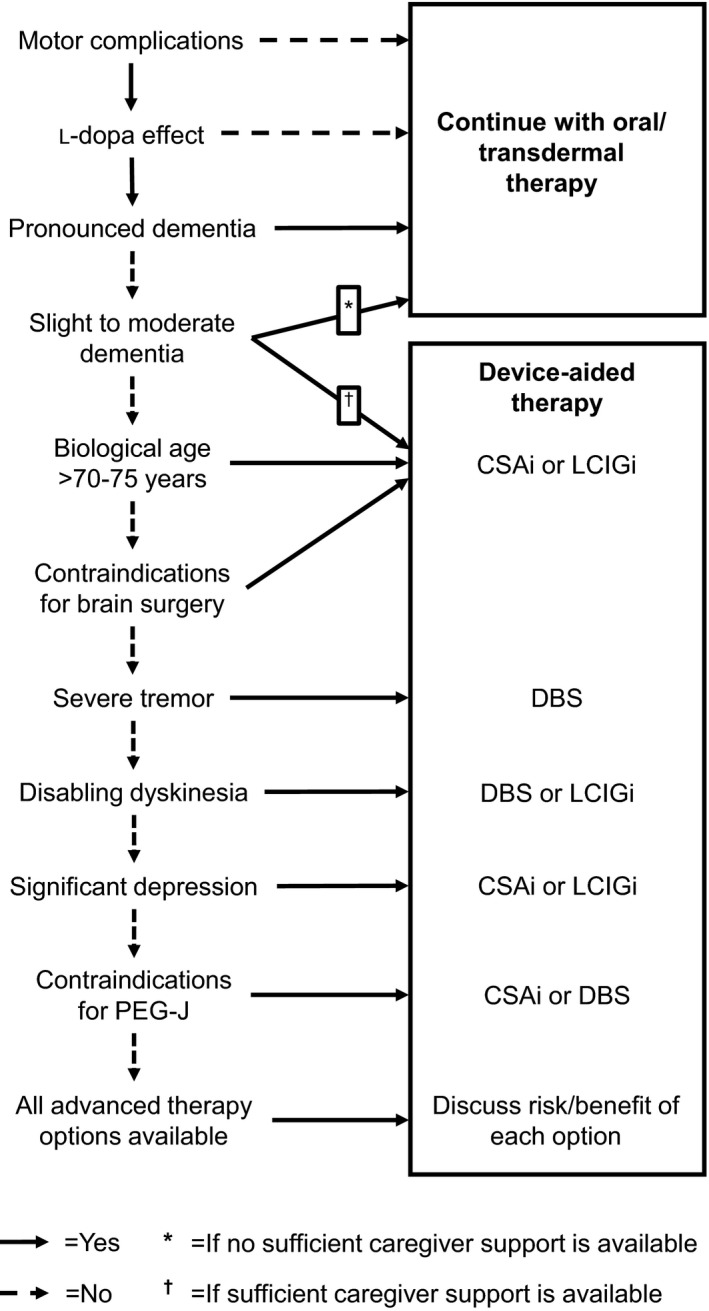

All the device‐aided therapies for PD require patients to exhibit motor complications and to respond to l‐dopa treatment (Fig. 2). Pronounced dementia is a contraindication for all device‐aided therapies, but both CSAi and LCIGi are also possible options for patients with slight to moderate dementia if there is enough caregiver support available to help with the handling of the device.13 DBS is unsuitable for patients with a biological age older than 70 to 75 years or with any contraindications for brain surgery, which makes CSAi and LCIGi the two remaining options for those patients. DBS is instead the primary option for patients with severe tremor and is together with LCIGi one of the two options for patients with disabling dyskinesia. Both CSAi and LCIGi are more suitable than DBS for patients with significant depression. Contraindications against the placement of a PEG‐J prohibit the use of LCIGi. If none of the strict contraindications or characterizing symptoms is present, all therapies are available and the risks and benefits of each option should be discussed with the patient.

Figure 2.

Algorithm for assessment of suitability for device‐aided therapies. CSAi, continuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusion; DBS, deep‐brain stimulation; LCIGi, l‐dopa‐carbidopa intestinal gel infusion.

Conclusions and Future Directions

We sought to bring further clarity to the process of selecting a suitable non‐oral CDD technique for patients at different stages of PD. The therapies included in this review have all been shown to result in significant improvements of both motor and non‐motor symptoms, but each therapy also has a number of characteristic advantages and drawbacks that need to be matched with the patient's symptomatology.

There were noteworthy differences between the CDD therapies in terms of study design. The clinical experience with CSAi is substantial, and its beneficial effect on patient outcomes has repeatedly been demonstrated in open‐label studies. Nonetheless, the need for RCTs to disambiguate the efficacy of CSAi remains urgent. RCTs with comparisons between the different device‐aided therapies are also warranted and would contribute much‐needed clarity to the subject.

The costs related to both CSAi and LCIGi are significant, and further cost reductions are needed to increase access to these therapies. Moreover, there is a need for further development of the non‐oral CDD techniques—both to increase their ease of use and to reduce the relatively frequent device‐related AEs. A reduction in the pump size and drug volume is needed as well as new routes of administration (e.g, subcutaneous l‐dopa infusion).

The benefits of non‐oral CDD have now been proven in blinded and controlled studies on both LCIGi and rotigotine. Although there is still much to learn on the physiological mechanisms of both CDD and CDS, CDD stands as a highly reasonable approach for treatment of PD.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

1. J.T.: Writing of the first draft, review, and critique

2.T.H.: Writing of the first draft, review, and critique

3.P.O.: Writing of the first draft, review, and critique

Disclosures

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest:

The authors report no sources of funding and J.T. reports no conflicts of interest. T.H. received economic compensation for lectures and/or consulting from AbbVie, NordicInfu Care, and UCB. P.O. received economic compensation for lectures and/or consulting from AbbVie, Britannia, Lundbeck, NordicInfu Care, Orion Pharma, and UCB.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 months:

J.T. reports no additional disclosures. T.H. received economic compensation for lectures and/or consulting from AbbVie, NordicInfu Care, and UCB. P.O. received economic compensation for lectures and/or consulting from AbbVie, Britannia, Lundbeck, NordicInfu Care, Orion Pharma, and UCB.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Stocchi F. The therapeutic concept of continuous dopaminergic stimulation (CDS) in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2009;15(suppl 3):S68–S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jenner P. Wearing off, dyskinesia, and the use of continuous drug delivery in disease. Neurol Clin 2013;31(suppl 3):S17–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chaudhuri KR, Rizos A, Sethi KD. Motor and nonmotor complications in Parkinson's disease: an argument for continuous drug delivery? J Neural Transm 2013;120:1305–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fahn S, Oakes D, Shoulson I, et al. Levodopa and the progression of Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2498–2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Warren Olanow C, Kieburtz K, Rascol O, et al. Factors predictive of the development of Levodopa‐induced dyskinesia and wearing‐off in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2013;28:1064–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de la Fuente‐Fernandez R, Sossi V, Huang Z, et al. Levodopa‐induced changes in synaptic dopamine levels increase with progression of Parkinson's disease: implications for dyskinesias. Brain 2004;127(Pt 12):2747–2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marrinan S, Emmanuel AV, Burn DJ. Delayed gastric emptying in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2014;29:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Storch A, Schneider CB, Wolz M, et al. Nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson disease: severity and correlation with motor complications. Neurology 2013;80:800–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Volkmann J, Albanese A, Antonini A, et al. Selecting deep brain stimulation or infusion therapies in advanced Parkinson's disease: an evidence‐based review. J Neurol 2013;260:2701–2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trenkwalder C, Chaudhuri KR, Garcia Ruiz PJ, et al. Expert Consensus Group report on the use of apomorphine in the treatment of Parkinson's disease—Clinical practice recommendations. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2015;21:1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McAfee DA, Hadgraft J, Lane ME. Rotigotine: the first new chemical entity for transdermal drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2014;88:586–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou CQ, Li SS, Chen ZM, Li FQ, Lei P, Peng GG. Rotigotine transdermal patch in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e69738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Odin P, Ray Chaudhuri K, Slevin JT, et al. Collective physician perspectives on non‐oral medication approaches for the management of clinically relevant unresolved issues in Parkinson's disease: consensus from an international survey and discussion program. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2015;21:1133–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rambour M, Moreau C, Salleron J, et al. Continuous subcutaneous infusion of apomorphine in Parkinson's disease: retrospective analysis of a series of 81 patients. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2014;170:205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Todorova A, Martinez‐Martin P, Martin A, Rizos A, Reddy P, Chaudhuri KR. Daytime apomorphine infusion combined with transdermal Rotigotine patch therapy is tolerated at 2 years: a 24‐h treatment option in Parkinson's disease. Basal Ganglia 2013;3:127–130. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martinez‐Martin P, Reddy P, Katzenschlager R, et al. EuroInf: a multicenter comparative observational study of apomorphine and levodopa infusion in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2015;30:510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Olanow CW, Kieburtz K, Odin P, et al. Continuous intrajejunal infusion of levodopa‐carbidopa intestinal gel for patients with advanced Parkinson's disease: a randomised, controlled, double‐blind, double‐dummy study. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:141–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fernandez HH, Standaert DG, Hauser RA, et al. Levodopa‐carbidopa intestinal gel in advanced Parkinson's disease: final 12‐month, open‐label results. Mov Disord 2015;30:500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Slevin JT, Fernandez HH, Zadikoff C, et al. Long‐term safety and maintenance of efficacy of levodopa‐carbidopa intestinal gel: an open‐label extension of the double‐blind pivotal study in advanced Parkinson's disease patients. J Parkinsons Dis 2015;5:165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Antonini A, Yegin A, Preda C, et al. Global long‐term study on motor and non‐motor symptoms and safety of levodopa‐carbidopa intestinal gel in routine care of advanced Parkinson's disease patients; 12‐month interim outcomes. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2015;21:231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zibetti M, Merola A, Artusi CA, et al. Levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel infusion in advanced Parkinson's disease: a 7‐year experience. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Antonini A, Odin P, Opiano L, et al. Effect and safety of duodenal levodopa infusion in advanced Parkinson's disease: a retrospective multicenter outcome assessment in patient routine care. J Neural Transm 2013;120:1553–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Buongiorno M, Antonelli F, Camara A, et al. Long‐term response to continuous duodenal infusion of levodopa/carbidopa gel in patients with advanced Parkinson disease: the Barcelona registry. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2015;21:871–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pickut BA, van der Linden C, Dethy S, Van De Maele H, de Beyl DZ. Intestinal levodopa infusion: the Belgian experience. Neurol Sci 2014;35:861–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reddy P, Martinez‐Martin P, Rizos A, et al. Intrajejunal levodopa versus conventional therapy in Parkinson disease: motor and nonmotor effects. Clin Neuropharmacol 2012;35:205–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nyholm D, Klangemo K, Johansson A. Levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel infusion long‐term therapy in advanced Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:1079–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nomoto M, Mizuno Y, Kondo T, et al. Transdermal rotigotine in advanced Parkinson's disease: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. J Neurol 2014;261:1887–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Timmermann L, Asgharnejad M, Boroojerdi B, Dohin E, Woltering F, Elmer LW. Impact of 6‐month earlier versus postponed initiation of rotigotine on long‐term outcome: post hoc analysis of patients with early Parkinson's disease with mild symptom severity. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015;16:1423–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mizuno Y, Nomoto M, Hasegawa K, et al. Rotigotine vs ropinirole in advanced stage Parkinson's disease: a double‐blind study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20:1388–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mizuno Y, Nomoto M, Kondo T, et al. Transdermal rotigotine in early stage Parkinson's disease: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Mov Disord 2013;28:1447–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jankovic J, Watts RL, Martin W, Boroojerdi B. Transdermal rotigotine: double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2007;64:676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parkinson Study Group . A controlled trial of rotigotine monotherapy in early Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol 2003;60:1721–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Giladi N, Boroojerdi B, Korczyn AD, et al. Rotigotine transdermal patch in early Parkinson's disease: a randomized, double‐blind, controlled study versus placebo and ropinirole. Mov Disord 2007;22:2398–2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Poewe WH, Rascol O, Quinn N, et al. Efficacy of pramipexole and transdermal rotigotine in advanced Parkinson's disease: a double‐blind, double‐dummy, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. LeWitt PA, Lyons KE, Pahwa R, SP 650 Study Group . Advanced Parkinson disease treated with rotigotine transdermal system: PREFER Study. Neurology 2007;68:1262–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Trenkwalder C, Kies B, Rudzinska M, et al. Rotigotine effects on early morning motor function and sleep in Parkinson's disease: a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled study (RECOVER). Mov Disord 2011;26:90–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nicholas AP, Borgohain R, Chana P, et al. A randomized study of rotigotine dose response on “off” time in advanced Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2014;4:361–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oertel W, LeWitt P, Giladi N, Ghys L, Grieger F, Boroojerdi B. Treatment of patients with early and advanced Parkinson's disease with rotigotine transdermal system: age‐relationship to safety and tolerability. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013;19:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim BH, Yu KS, Jang IJ, et al. Pharmacokinetic properties and tolerability of rotigotine transdermal patch after repeated‐dose application in healthy Korean volunteers. Clin Ther 2015;37:902–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]