Abstract

Background

The reasons underlying the loss of efficacy of deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the thalamic nucleus ventralis intermedius (VIM‐DBS) over time in patients with essential tremor are not well understood.

Methods

Long‐term clinical outcome and stimulation parameters were evaluated in 14 patients with essential tremor who underwent VIM‐DBS. The mean ± standard deviation postoperative follow‐up was 7.7 ± 3.8 years. At each visit (every 3–6 months), tremor was assessed using the Fahn‐Tolosa‐Marin tremor rating scale (FTM‐TRS) and stimulation parameters were recorded (contacts, voltage, frequency, pulse width, and total electrical energy delivered by the internal generator [TEED 1sec]).

Results

The mean reduction in FTM‐TRS score was 73.4% at 6 months after VIM‐DBS surgery (P < 0.001) and 50.1% at the last visit (P < 0.001). The gradual worsening of FTM‐TRS scores over time fit a linear regression model (coefficient of determination [R2] = 0.887; P < 0.001). Stimulation adjustments to optimize tremor control required a statistically significant increase in voltage (P = 0.01), pulse width (P = 0.01), frequency (P = 0.02), and TEED 1sec (P = 0.008). TEED 1sec fit a third‐order polynomial curve model throughout the follow‐up period (R2 = 0.966; P < 0.001). The initial exponential increase (first 4 years of VIM‐DBS) was followed by a plateau and a further increase from the seventh year onward.

Conclusions

The current findings suggest that the waning effect of VIM‐DBS over time in patients with essential tremor may be the consequence of a combination of factors. Superimposed on the progression of the disease, tolerance can occur during the early years of stimulation.

Keywords: essential tremor, deep brain stimulation, long‐term efficacy, tolerance, disease progression

Essential tremor (ET) is one of the most common neurological disorders.1 ET is a slowly progressive disease with a variable clinical course and response to pharmacological treatment that can result in significant functional disability in some patients.2, 3, 4 Deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the thalamic nucleus ventralis intermedius (VIM‐DBS) is an effective surgical treatment for selected patients with drug‐refractory ET.5 However, loss of efficacy over time gives cause for concern.6, 7 Up to one‐third of patients experience a worsening of tremor over months to years, and many need VIM‐DBS to be reprogrammed with higher stimulation parameters to control tremor deterioration.4 A recent study suggested that the potential loss of benefit of VIM‐DBS should be discussed during patient counselling on the durability of the expected benefit.8

The underlying reasons for the decline in tremor control by VIM‐DBS are not well understood. Tolerance to stimulation7, 9 and disease progression10 have been proposed as the most likely causes. Other factors, such as suboptimal lead placement,11 gradual loss of the microthalamotomy effect,12 and the potentially increased impedance in brain tissue over time,12, 13 may also play a role. To elucidate the possible causes of the loss of benefits from VIM‐DBS in the control of ET, we evaluated long‐term clinical outcome and stimulation parameters, particularly total electrical energy delivered by the internal generator (TEED1sec),14 in a series of patients who had drug‐refractory ET treated with VIM‐DBS at a single center.

Patients and Methods

This retrospective review of prospectively collected data was approved by the local ethics committee. We included patients with disabling, drug‐refractory ET who underwent lead implantation and programming with either unilateral or bilateral VIM‐DBS at Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (Madrid, Spain) and were followed for at least 2 years after surgery. Target localization was supported by intraoperative microrecordings, the clinical effect of intraoperative electrical stimulation, and postoperative stereotactic magnetic resonance imaging. We excluded patients who had no benefit after initial programming and those who lost the initial benefit within 6 months despite extensive reprogramming sessions. The clinical characteristics recorded included age, sex, duration of ET until surgery, current medication, and medication before VIM‐DBS.

All patients were implanted with devices from Medtronic Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA), which induce constant voltage stimulation. The implantable pulse generator was usually turned on 1–3 weeks after implantation. During the first 2 or 3 months, the stimulation parameters were adjusted to obtain maximal control of tremor without side effects. Patients were followed at routinely scheduled visits every 3–6 months. Additional unscheduled visits were allowed if required, according to the patient's clinical situation.

ET was assessed using the Fahn‐Tolosa‐Marin tremor rating scale (FTM‐TRS)15 before surgery and at each follow‐up visit. This scale evaluates tremor (part A), hand function (part B), and activities of daily living (part C). Stimulation settings, including type of stimulation (active contacts, monopolar/bipolar) amplitude (V), pulse width (μsec), and frequency (Hz), were registered at each follow‐up visit, and an analysis of impedance (Ω) was performed to rule out possible open or short circuits. Stimulation settings were reprogrammed to optimize the control of tremor when deemed necessary. This process usually involved increases in stimulation amplitude of from 0.2 to 0.5 V, increases in pulse width of 30 μsec, or frequency increases to a maximum of 190 Hz. The TEED1sec by the internal pulse generator was calculated for each follow‐up visit using the following equation: TEED1sec(J) = ([voltage2 × frequency × pulse width]/impedance) × 1 second.14 Like in previous studies, an impedance of 1000 Ω was adopted to calculate TEED1sec.16

The statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To assess TEED1sec and FTM‐TRS over time, fitting curves were constructed using regression analysis. The coefficient of determination (R2) was used to assess the fit of the regression line to the data collected. The Wilcoxon signed‐rank test was used to determine statistically significant changes over time in the FTM‐TRS scores and stimulation parameters. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ) was used to measure statistical dependence between stimulation parameters and FTM‐TRS scores. The results are presented as mean values ± standard deviation. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

In total, 14 patients (10 men) were included in the study. Two other patients were excluded because of poor initial benefit due to suboptimal placement of the electrodes.

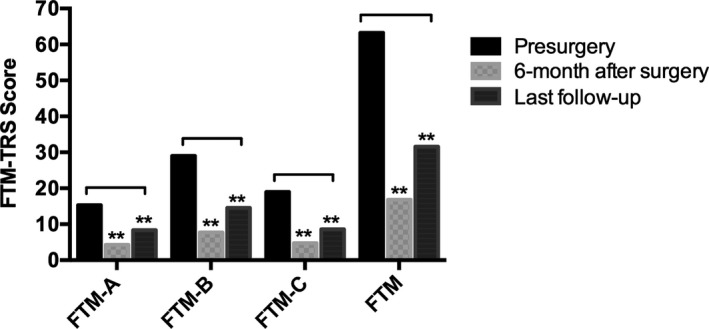

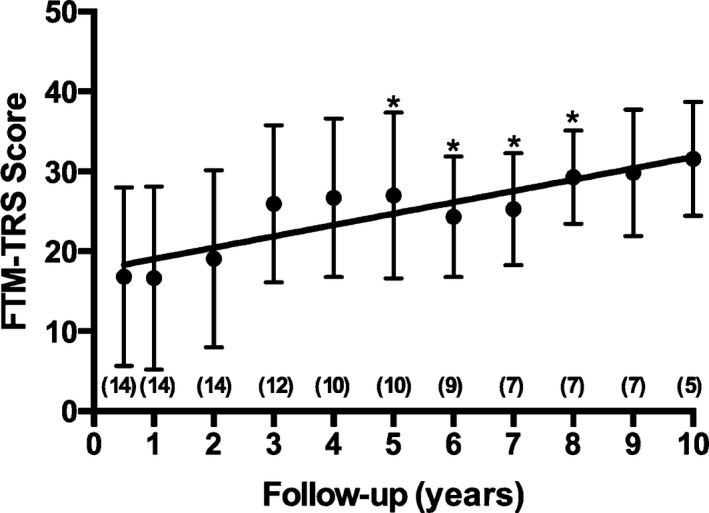

Eleven patients underwent bilateral VIM‐DBS placement, and 3 received unilateral leads. The mean age ± standard deviation at implantation was 61 ± 2.5 years. The mean duration of symptoms before surgery was 25 ± 10.5 years. The mean duration of follow‐up after surgery was 92.6 ± 45.5 months. Medications for ET were discontinued completely after VIM‐DBS surgery in 10 patients (71.5%), usually within the first 6 months. The FTM‐TRS scores and subscores over time are shown in Figure 1. The mean reduction in the total FTM‐TRS score was 73.4% 6 months after implantation (baseline, 63.3 ± 9.9; 6‐month follow‐up, 16.8 ± 11.2; P < 0.01) and 50.1% at the last follow‐up visit (baseline, 63.29; last follow‐up, 31.6 ± 8.2; P < 0.01). Similar statistically significant reductions were obtained for all FTM‐TRS subscores during the follow‐up period (Fig. 1). Although tremor improved throughout the follow‐up period, we detected a steady, mild, progressive worsening of FTM‐TRS scores that began after the first year of VIM‐DBS and fit a linear regression model (R2 = 0.887; P < 0.001) (Figs. 2, 3)

Figure 1.

Mean Fahn‐Tolosa‐Marin (FTM) tremor rating scale scores and subscores (FTM‐A, FTM‐B, and FTM‐C) before surgery, 6 months after surgery, and at the last follow‐up visit are illustrated. This scale includes evaluation of tremor (part A), hand function (part B), and activities of daily living (part C). Double asterisks indicate P < 0.01. The results are presented as mean values.

Figure 2.

Progress of scores on the Fahn‐Tolosa‐Marin tremor rating scale (FTM‐TRS) after surgery is illustrated. A steady, mild, progressive worsening of FTM‐TRS scores was observed beginning the first year after thalamic nucleus ventralis intermedius deep brain stimulation (VIM‐DBS) implantation. The FTM‐TRS score increased significantly compared with scores at the assessment 6 months after surgery (an asterisk indicates P < 0.05). The results are presented as mean values ± standard deviation. The numbers in parentheses represent patients who were included in the follow‐up at each time interval.

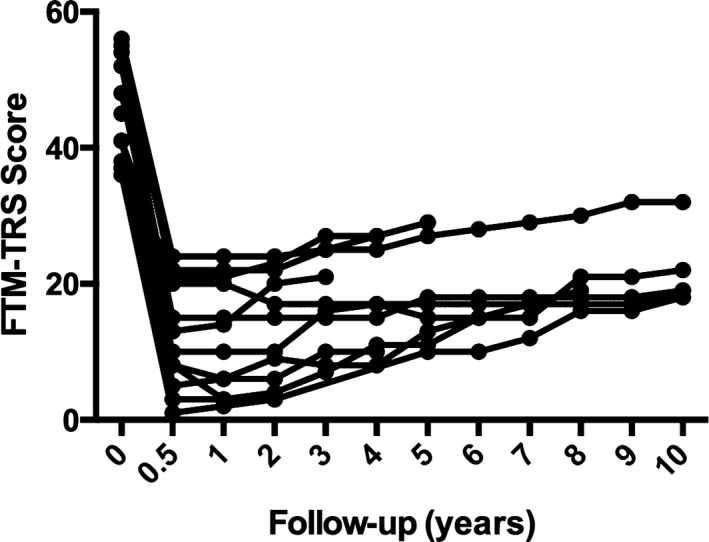

Figure 3.

Total scores on the Fahn‐Tolosa‐Marin tremor rating scale (FTM‐TRS) are illustrated for individual patients during the follow‐up period.

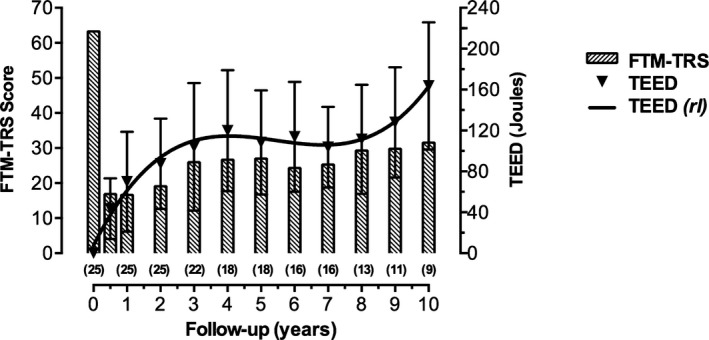

To maintain an appropriate clinical response, stimulation parameters were adjusted if necessary (see above) throughout the follow‐up period (Table 1). At the last visit, significant increases were detected in voltage (2.1 ± 0.6 V at 6 months after surgery; 3.5 ± 0.6 V at the final visit; P = 0.01), pulse width (66.0 ± 19.4 μsec at 6 months after surgery; 90.0 ± 15.0 μsec at the final visit; P = 0.01), and frequency (130 ± 1.0 Hz at 6 months after surgery; 142.0 ± 10.0 Hz at the final visit; P = 0.02). TEED1sec increased significantly over time (43.1 ± 29.8 joules at 6 months after surgery, and 163.5 ± 62.1 joules at the final visit; P < 0.001) fitting a third‐order polynomial regression model (R2 = 0.966; P = 0.008) (Fig. 4). A significant correlation was observed between FTM‐TRS scores and TEED1sec values during the follow‐up period (ρ = 0.927; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Parameters for deep brain stimulation of the thalamic nucleus ventralis intermedius 6 months after surgery and at the last follow‐up

| VIM‐DBS Parameters | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Months | Last Follow‐up | ||||||||||

| Patient | Electrodes | Stimulation | Contacts | V, v | F, Hz | P, μsec | Stimulation | Contacts | V, v | F, Hz | P, μsec |

| 1 | Left | Monopolar | 2(−) | 1.8 | 130 | 60 | Monopolar | 3(−) | 3.1 | 130 | 60 |

| Right | Monopolar | 6(−) | 1.9 | 130 | 60 | Monopolar | 6(−) | 2.8 | 140 | 90 | |

| 2 | Left | Monopolar | 0(−) | 1.0 | 130 | 60 | Monopolar | 0(−) | 1.5 | 130 | 60 |

| 3 | Left | Bipolar | 2(−)3(+) | 2.4 | 130 | 60 | Bipolar | 2(−)3(+) | 3.7 | 130 | 90 |

| Right | Bipolar | 6(−)5(+) | 1.8 | 130 | 60 | Bipolar | 6(−)5(+) | 3.7 | 130 | 90 | |

| 4 | Left | Monopolar | 0(−)1(−) | 2.9 | 130 | 60 | Bipolar | 0(−)1(+) | 3.7 | 140 | 120 |

| Right | Monopolar | 4(−)5(−) | 3.3 | 130 | 60 | Bipolar | 4(−)5(+) | 3.6 | 140 | 60 | |

| 5 | Left | Monopolar | 1(−) | 1.5 | 130 | 60 | Monopolar | 1(−) | 2.4 | 130 | 60 |

| Right | Monopolar | 5(−) | 1.7 | 130 | 60 | Monopolar | 5(−) | 3.2 | 130 | 60 | |

| 6 | Left | Monopolar | 5(−) | 2.2 | 130 | 60 | Bipolar | 5(−)6(+) | 3.2 | 140 | 90 |

| 7 | Left | Monopolar | 1(−) | 2.4 | 130 | 60 | Bipolar | 1(−)2(+) | 2.8 | 140 | 90 |

| Right | Monopolar | 5(−) | 1.7 | 130 | 60 | Monopolar | 5(−) | 2.8 | 140 | 60 | |

| 8 | Left | Monopolar | 1(−) | 1.4 | 130 | 60 | Bipolar | 2(−)3(+) | 3.8 | 140 | 60 |

| Right | Bipolar | 7(−)4(+) | 1.9 | 130 | 150 | Bipolar | 5(−)6(+) | 4.2 | 130 | 90 | |

| 9 | Left | Bipolar | 0(−)1(+) | 2.0 | 130 | 60 | Monopolar | 0(−)1(−) | 3.7 | 145 | 90 |

| 10 | Left | Bipolar | 0(−)1(+) | 3.0 | 130 | 90 | Monopolar | 5(−) | 3.7 | 145 | 90 |

| Right | Monopolar | 4(−) | 1.5 | 130 | 60 | Bipolar | 1(−)2(+) | 4.1 | 145 | 90 | |

| 11 | Left | Monopolar | 1(−) | 3.5 | 130 | 60 | Monopolar | 0(−) | 3.5 | 130 | 90 |

| Right | Bipolar | 3(−)1(+) | 2.5 | 130 | 60 | Bipolar | 0(−)2(+) | 3.7 | 130 | 90 | |

| 12 | Left | Monopolar | 0(−) | 1.5 | 130 | 60 | Monopolar | 1(−) | 2.9 | 130 | 60 |

| Right | Monopolar | 6(−) | 2.0 | 130 | 60 | Monopolar | 6(−) | 3.4 | 130 | 60 | |

| 13 | Left | Monopolar | 2(−) | 1.7 | 135 | 60 | Monopolar | 1(−) | 3.9 | 145 | 90 |

| Right | Bipolar | 0(−)1(+) | 3.0 | 139 | 60 | Bipolar | 2(−)3(+) | 3.2 | 160 | 90 | |

| 14 | Left | Bipolar | 0(−)1(+) | 3.0 | 130 | 90 | Bipolar | 3(+)2(−)1(−) | 3.8 | 145 | 120 |

| Right | Bipolar | 0(−)1(+) | 1.5 | 130 | 60 | Bipolar | 0(−)1(+) | 2.0 | 130 | 60 | |

VIM‐DBS, deep brain stimulation of the thalamic nucleus ventralis intermedius; V, voltage; F, frequency; P, pulse width; (−), negative; (+), positive.

Figure 4.

Progress of the total electrical energy delivered (TEED 1sec) and scores on the Fahn‐Tolosa‐Marin tremor rating scale (FTM‐TRS) during follow‐up are illustrated. The curve shows an initial exponential increase in TEED 1sec during the first 4 years followed by a plateau and a further increase from the seventh year after surgery onward (rl indicates regression line). A gradual worsening of FTM‐TRS scores began the first year after thalamic nucleus ventralis intermedius deep brain stimulation implantation. Results are presented as mean values ± standard deviation. Numbers in parentheses represent individual electrodes at each time interval.

Discussion

Our findings confirm that VIM‐DBS is an effective long‐term treatment for ET. However, although stimulation provided benefit throughout the follow‐up period (more than 10 years in some patients), we observed a slowly progressive worsening of ET scores over time, despite adjusting stimulation parameters to optimize tremor control. Several reasons have been proposed for the decline in the clinical efficacy of VIM‐DBS in ET, including tolerance,7, 8, 9 natural disease progression,10 suboptimal electrode placement,11 loss of the microthalamotomy effect,12 increased impedance in brain tissue over time,12, 13 and long‐term, stimulation‐induced effects.17

The loss of efficacy of VIM‐DBS over years cannot be explained by the “microthalamotomy effect,” which usually occurs over weeks to months.12 Suboptimal lead placement also seems to be an unlikely explanation in this study, because patients who had poor benefit after initial programming were excluded.

Despite extensive reprogramming of stimulation parameters, we detected a slow, declining benefit (as measured by the FTM‐TRS) that resembled the worsening in tremor scores over time observed in epidemiological studies on the natural progression of ET.3, 18 This suggests disease progression as a plausible cause for the partial loss of efficacy in tremor control over time. In 1 of those studies, the average annual increase in severity of ET from baseline ranged from 3.1% to 5.3%.3 The hypothesis of disease progression is also supported by the worsening of tremor scores in other small VIM‐DBS series with long‐term follow‐up.19, 20 In addition, findings from 2 studies of VIM‐DBS administered over a period of years showed that tremor scores when stimulation was turned off for 15 or 30 minutes were higher than the baseline scores (preimplantation).4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 However, these observations should be interpreted with caution because of the short stimulation washout time and the possibility of a rebound effect.

As the disease progresses, some components of tremor, especially severe limb action tremor (which is usually more disabling than postural tremor in hand function and activities of daily living), may be more difficult to control using VIM‐DBS.19 With the progression of ET, the modulation of the synchronized oscillatory cerebellothalamocortical pathway induced by high‐frequency stimulation of the thalamic nucleus ventralis intermedius gradually loses effectiveness, perhaps because tremor may grow more dependent upon other pathophysiological factors that are not ameliorated by VIM‐DBS.

Tolerance to stimulation has also been considered a possible explanation for the gradual loss of efficacy of VIM‐DBS over time. Several investigators have reported the need to increase voltage, amplitude, or frequency during postoperative long‐term programming to maintain the clinical benefit of VIM‐DBS.7, 8, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 This observation is supported by the observation that stimulation holidays temporarily restored the efficacy of VIM‐DBS and that patients may benefit from intermittent use of the stimulator, usually turning it off during sleep.12, 23, 24, 25 Another study showed that the systematic optimization of VIM‐DBS parameters in ET led to a short‐term improvement, which habituated over time, suggesting that tolerance to stimulation could be improved using alternating stimulation protocols.10

We used TEED1sec—a measurement of the total electric energy delivered by the internal generator—to globally assess VIM‐DBS parameters. We found that TEED1sec increased exponentially over the first 4 years of VIM‐DBS to optimized tremor control, followed by a plateau of about 3 years, and a subsequent raise. This observation suggests that the development of tolerance to VIM‐DBS occurs during the first years of treatment, which may be related to the oscillatory nature of the cerebellothalamocortical circuit observed in this disease, with discharges of thalamic neurons coherent with the frequency of the peripheral tremor.26 High‐frequency thalamic stimulation could temporarily modulate this pathway, but subsequent habituation might occur through resetting of the thalamic oscillatory drive. Tolerance to DBS in other movement disorders has rarely been reported.

The increase in TEED1sec after 7 years of VIM‐DBS after a stable period of several years may be the consequence of increasing stimulation parameters to try to improve the progression of clinically disabling tremor. Gliosis around the placement of the electrodes,13, 27, 28, 29, 30 although it cannot be completely ruled out, seems an unlikely cause for the late decline of VIM‐DBS efficacy in this study.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the waning effect of VIM‐DBS over time in patients with ET may be the consequence of a combination of factors. Superimposed on the progression of the disease, which is present throughout the follow‐up period, tolerance may occur during the early years of stimulation. Nevertheless, despite these considerations, VIM‐DBS remains an effective long‐term treatment for severe, otherwise untreatable ET. New developments in stimulation devices and a better understanding of tremor pathophysiology should improve the efficacy of VIM‐DBS in ET.

Author Roles

1. Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; 2. Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; 3. Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

P.M.R.C.: 1A, 1B, 3A

A.V.: 1A, 1B, 3A

C.F.C: 1C, 3B

J.G.: 1C; 3B

B.D.L.C.‐F.: 1A, 3B

F.G.: 1A, 3B

Disclosures

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: No specific funding was received for this work. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

Financial Disclosures for the previous 12 months: Francisco Grandas has received honoraria from AbbVie for Advisory Board participation and a research grant from UCB. The remaining authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jose María Bellón for his review of the statistical analysis presented in this article.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Louis ED, Ferreira JJ. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Mov Disord 2010;25:534–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jankovic J. Essential tremor: a heterogenous disorder. Mov Disord 2002;17:638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Louis ED, Agnew A, Gillman A, Gerbin M, Viner AS. Estimating annual rate of decline: prospective, longitudinal data on arm tremor severity in two groups of essential tremor cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:761–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baizabal‐Carvallo JF, Kagnoff MN, Jimenez‐Shahed J, Fekete R, Jankovic J. The safety and efficacy of thalamic deep brain stimulation in essential tremor: 10 years and beyond. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pahwa R, Lyons K, Koller WC. Surgical treatment of essential tremor. Neurology 2000;54(11 suppl 4):S39–S44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar R, Lozano AM, Sime E, Lang AE. Long‐term follow‐up of thalamic deep brain stimulation for essential and parkinsonian tremor. Neurology 2003;61:1601–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hariz MI, Shamsgovara P, Johansson F, Hariz G, Fodstad H. Tolerance and tremor rebound following long‐term chronic thalamic stimulation for Parkinsonian and essential tremor. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 1999;72:208–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shih LC, LaFaver K, Lim C, Papavassiliou E, Tarsy D. Loss of benefit in VIM thalamic deep brain stimulation (DBS) for essential tremor (ET): how prevalent is it? Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013;19:676–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barbe MT, Liebhart L, Runge M, et al. Deep brain stimulation in the nucleus ventralis intermedius in patients with essential tremor: habituation of tremor suppression. J Neurol 2011;258:434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Favilla CG, Ullman D, Wagle Shukla A, Foote KD, Jacobson CE, Okun MS. Worsening essential tremor following deep brain stimulation: disease progression versus tolerance. Brain 2012;135(pt 5):1455–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Okun MS, Tagliati M, Pourfar M, et al. Management of referred deep brain stimulation failures. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1250–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Benabid AL, Pollak P, Gervason C, et al. Long‐term suppression of tremor by chronic stimulation of the ventral intermediate thalamic nucleus. Lancet 1991;337:403–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boockvar JA, Telfeian A, Baltuch GH, et al. Long‐term deep brain stimulation in a patient with essential tremor: clinical response and postmortem correlation with stimulator termination sites in ventral thalamus: case report. J Neurosurg 2000;93:140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koss AM, Alterman RL, Tagliati M, Shils JL. Calculating total electrical energy delivered by deep brain stimulation systems [letter]. Ann Neurol 2005;58:168; author reply 168–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fahn S, Tolosa E, Marin C. Clinical rating scale for tremor In: Jankovic J, Tolosa E, eds. Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders, 2nd ed Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1993:271–280. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lozano AM, Hallett M. Brain stimulation In: Aminoff MJ, Boller F, Swaab DF, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol 116, 3rd Series. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2013:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pilitsis JG, Metman LV, Toleikis JR, Hughes LE, Sani SB, Bakay RA. Factors involved in long‐term efficacy of deep brain stimulation of the thalamus for essential tremor. J Neurosurg 2008;109:640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Louis ED, Gerbin M, Galecki M. Essential tremor 10, 20, 30, 40: clinical snapshots of the disease by decade of duration. Eur J Neurol 2013;20:949–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sydow O, Thobois S, Alesch F, Speelman JD. Multicentre European study of thalamic stimulation in essential tremor: a six year follow up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1387–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rehncrona S, Johnels B, Widner H, Törnqvist A‐L, Hariz M, Sydow O. Long‐term efficacy of thalamic deep brain stimulation for tremor: double‐blind assessments. Mov Disord 2003;18:163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koller WC, Lyons KE, Wilkinson SB, Troster AI, Pahwa R. Long‐term safety and efficacy of unilateral deep brain stimulation of the thalamus in essential tremor. Mov Disord 2001;16:464–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Limousin P, Speelman JD, Gielen F, Janssens M. Multicentre European study of thalamic stimulation in parkinsonian and essential tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:289–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pahwa R, Lyons KE, Wilkinson SB, et al. Long‐term evaluation of deep brain stimulation of the thalamus. J Neurosurg 2006;104:506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamamoto T, Katayama Y, Kano T, Kobayashi K, Oshima H, Fukaya C. Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of parkinsonian, essential, and poststroke tremor: a suitable stimulation method and changes in effective stimulation intensity. J Neurosurg 2004;101:201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang K, Bhatia S, Oh MY, Cohen D, Angle C, Whiting D. Long‐term results of thalamic deep brain stimulation for essential tremor. J Neurosurg 2010;112:1271–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hua SE, Lenz FA. Posture‐related oscillations in human cerebellar thalamus in essential tremor are enabled by voluntary motor circuits. J Neurophysiol 2005;93:117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. DiLorenzo DJ, Jankovic J, Simpson RK, Takei H, Powell SZ. Long‐term deep brain stimulation for essential tremor: 12‐year clinicopathologic follow‐up. Mov Disord 2010;25:232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. DiLorenzo DJ, Jankovic J, Simpson RK, Takei H, Powell SZ. Neurohistopathological findings at the electrode‐tissue interface in long‐term deep brain stimulation: systematic literature review, case report, and assessment of stimulation threshold safety. Neuromodulation 2014;17:405–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sun DA, Yu H, Spooner J, et al. Postmortem analysis following 71 months of deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus for Parkinson disease. J Neurosurg 2008;109:325–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stock G, Sturm V, Schmitt HP, Schlör KH. The influence of chronic deep brain stimulation on excitability and morphology of the stimulated tissue. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1979;47:123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]