Abstract

Background

Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the pancreas (SCP) is a rare histologic subtype of undifferentiated pancreatic carcinoma. Historically, this has been associated with a worse overall prognosis than adenocarcinoma. However, the clinical course and surgical outcomes of SCP remain poorly characterized owing to its rarity.

Methods

A single-institution, prospectively maintained database was queried for patients who underwent pancreatic resection with a final diagnosis of SCP. We describe their histology, clinicopathologic features, and perioperative outcomes. Survival data are highlighted, and common traits of long-term survivors are examined.

Results

Over a 25-year period, 7009 patents underwent pancreatic resection at our institution. Eight (0.11%) were diagnosed with SCP on final histopathology. R0 resection was achieved in six patients (75%). Four patients had early recurrence leading to death (<3 months). Two (25%) experienced long-term survival (>5 years), with the longest surviving nearly 16 years despite the presence of lymph node metastasis. There were no deaths attributed to perioperative complications. Both long-term survivors had disease in the body/tail of the pancreas and received adjuvant radiotherapy. One also received adjuvant gemcitabine-based chemotherapy.

Conclusions

SCP is a rarely appreciated subset of pancreatic malignancy that does not necessarily portend to a uniformly dismal prognosis. Although some have rapid recurrence and an early demise, long-term survival may be possible. Future studies are needed to better define the cohort with potential for long-term survival so that aggressive therapies may be tailored appropriately in this patient subset.

Keywords: Sarcomatoid carcinoma, Survival, Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is an aggressive malignancy that continues to be a leading cause of mortality. An estimated 53,070 new cases are expected to occur in the United States in 2016, with approximately 42,000 deaths.1 Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the pancreas (SCP) is a rarely observed malignant subtype characterized by a predominance of spindle cells and sarcomatous morphologic features with epithelial derivation.2–4 This histologic feature is distinct from sarcoma, which is broadly defined as a tumor of mesenchymal differentiation. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of gastrointestinal tumors identifies SCP as a subset of the broad class of undifferentiated carcinomas. Other undifferentiated carcinomas that can occur in the pancreas include giant cell tumors and pleomorphic undifferentiated carcinomas (often termed anaplastic carcinoma).5 Although undifferentiated carcinoma of the pancreas has a reported incidence of 5%, SCP is exceptionally rare. Most examples are found in the literature only as case reports.6

Treatment for pancreatic adenocarcinoma as a whole remains challenging. Complete surgical extirpation is the only chance of cure, with 5-year survival rates of approximately 20%.7,8 Although no direct comparisons exist, SCP has historically been thought to have a long-term prognosis that is worse than ductal adenocarcinoma.2,9,10 Despite aggressive surgical management, median postoperative survival has been consistently reported at less than 1 year, with many succumbing to early carcinomatosis.2,9–12 Owing to the rarity of disease, the clinical course, surgical outcomes, and optimal treatment strategies for SCP are poorly characterized. In this study, we report our institution’s experience with sarcomatoid carcinoma to further characterize the clinicopathological features, surgical outcomes, and survival data in the individuals that undergo resection for this rare diagnosis.

Methods

A retrospective cohort analysis of a prospectively managed database was conducted of patients who underwent pancreatectomy with curative intent at the Johns Hopkins Hospital from October 1991 to December 2015. Internal Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the creation and use of this deidentified database for research purposes with waiver of informed consent.

Cases were initially identified by searching our pathology database for the terms “sarcomatoid”, “sarcomatous” and “spindle cell”. Patients identified had a primary diagnosis consistent with SCP and were reviewed by our pancreatic pathologists. Available cases had slides rereviwed and diagnosis confirmed. The histopathologic diagnosis of SCP was defined as the presence of poorly differentiated or anaplastic cells with a predominance of spindle cells, sarcomatoid features, and epithelial derivation. Pathology suggestive of pancreatic sarcoma or anaplastic carcinoma without sarcomatoid features was excluded.

Patient demographics, characteristics, operative, and perioperative outcomes were assessed via chart review. Individuals who obtained initial workup or neoadjuvant/ adjuvant treatment at outside institutions were included. Perioperative mortality was defined as death within 30 days of the operative date or mortality before hospital discharge from index admission. Complications were graded by the Clavien-Dindo scale.13 Overall survival was calculated from the date of surgery. Date of death was obtained from medical records, social security death index, or local obituaries.

Results

From October 1991 to December 2015, 7009 patients underwent pancreatic resections, eight (0.11%) patients had a final pathologic diagnosis of SCP. The median patient age was 66 years (range:54–80).Three patients were male(37.5%).The majority of patients presented with vague back or abdominal pain (62.5%) and the remaining were asymptomatic (37.5%) on initial preoperative visit with tumor found incidentally. Additional findings on presentation included jaundice (12.5%) and weight loss (12.5%). Preoperative workup included multiphase CT scan. Preoperative imaging was unavailable for review in two patients; however, of the images available, pancreatic ductal dilatation was appreciated in four cases (66%), atrophy of remaining pancreas in three cases (50%), a hypodense lesion in five cases (83%), cystic appearance in two cases (33%), heterogenous enhancement in two cases (33%), and venous phase peripheral enhancement in two cases (33%). Tumor size in greatest dimension was a median of 5 cm with range of 3–15cm. Preoperative tissue sampling by needle biopsy was obtained in four patients: two (50%) were identified as pancreatic adenocarcinoma, one(25%)aspleomorphicadenocarcinoma,andone (25%) as atypical epithelioid cells insufficient for diagnosis. Patient cohort characteristics are represented in Table 1.

Table 1 –

Characteristics of patients with sarcomatoid carcinoma of the pancreas.

| Sarcomatoid cancer patients (n = 8) | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean age (years), range | 67.1 (54–80) |

| Tumor size greatest dimension (cm) median, range | 5 (3–15) |

| R0 resection | 6 (75%) |

| Node involvement (≥1) | 6 (75%) |

| >5-year survival | 2 (25%) |

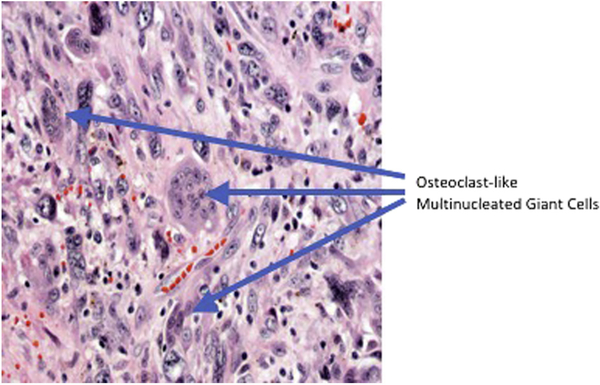

Pathologic analysis revealed a diagnosis of SCP in all cases. Two cases included the presence of mixed osteoclast-like giant cells (OCGCs). Pathologic grade ranged from poorly differentiated (43%) to anaplastic undifferentiated (57%). Five (62%) revealed lymphovascular invasion, and perineural invasion was present in four(50%)cases. Two(25%)subjects did not have any lymph node metastasis appreciated, whereas the remaining subjects had atleast one lymph node positive for metastatic carcinoma. Of note, the longest survivor did have lymph node metastasis in one of 22 nodes at the time of operation.

An R0 resection was achieved in 75% of cases, one of which required a vascular resection of the superior mesenteric vein. Of the remaining cases, one R1 resection (12.5%) had carcinoma at the posterior soft tissue margin following distal pancreatectomy, and an R2 resection (12.5%) found superior mesenteric artery involvement with gross tumor left behind. Neoadjuvant radiation and gemcitabine based therapy was received by one patient (12.5%). Two (37.5%) received adjuvant chemotherapy, and two (37.5%) had adjuvant radiotherapy. Both long-term survivors had disease in the body or tail of the pancreas and received adjuvant radiotherapy. One of the long-term survivors also received adjuvant gemcitabine-based chemotherapy. Individual patient clinicopathologic outcomes represented in Table 2.

Table 2 –

Clinicopathologic outcomes of patients with sarcomatoid carcinoma of the pancreas in our series.

| Case | Sex,age | Size (cm) | Neoadjuvant treatment | Adjuvant treatment | Surgery type | Margin status | LN status | LVI/PNI | Presence of OCGC | Last follow-up | Survival | Recurrence pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F, 67 | 4 | N | N | PD | R2 | 1/7 | N/N | N | 2 mo | 2 mo | NR |

| 2 | F, 80 | 5 | N | N | PD | R0 | 1/20 | Y/Y | Y | 1 mo | NR-live* | NR |

| 3 | F, 63 | 5.7 | N | N | Distal | R1 | 2/32 | N/Y | N | 1 mo | 1 mo | Carcinomatosis |

| 4 | F, 56 | 5 | Gemcitabine cisplatin + radiation | Capecitabine | TP | R0 | 0/10 | N/N | N | 3 mo | NR-live* | NR |

| 5 | M, 79 | 4 | N | N | PD | R0 | 13/17 | Y/Y | N | 3 mo | 3 mo | Local and hepatic |

| 6 | M, 54 | 3 | N | Gemcitabine, capecitabine + radiation | Distal | R0 | 0/27 | N/N | N | 5y 1 mo | Live* | None |

| 7 | M, 65 | 15 | N | N | Distal | R0 | 29/38 | Y/Y | Y | 3 mo | 3 mo | NR |

| 8 | F, 73 | 9 | N | Radiation | PD + TG | R0 | 1/24 | N/N | N | 15y 8 mo | 15y 8 mo | None |

F = female; M = male; N = no; Y = yes; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy; distal = distal pancreatectomy; TP = total pancreatectomy; TG = total gastrectomy; LVI = lymphovascular invasion; PNI = perineural invasion; OCGC = osteoglastic like giant cells; NR = not recorded/unknown; LN = lymph node.

Living patient.

Survival was noted to range from 2 months to nearly 16 years. Four patients had early recurrence leading to death <3 months, and two (25%) experienced long-term survival (>5 years). There were no deaths attributed to perioperative complications in this cohort. Postoperative complications occurred in 50% of patients, three classified as grade II requiring pharmacologic intervention only: either antibiotics or antiarrhythmic medications. One patient required postoperative interventional radiology-guided drain placement (Clavien-Dindo grade IIIa) for a peripancreatic collection. This complication corresponded with the shortest survivor in the cohort; however, the patient’s demise was attributed to carcinomatosis with concomitant malignant bowel obstruction. There were no long-term survivors among those with OCGC identified on histopathology.

Discussion

Undifferentiated carcinoma of the pancreas is a “catch all” term representing a set of rare tumors that account for as many as 5% of pancreatic neoplasms.6 The WHO classification of undifferentiated carcinoma includes many subsets and a variety of terms that are used inconsistently in the literature. Commonly used terms include pleomorphic carcinoma, giant cell carcinoma, large-cell carcinoma, and sarcomatoid carcinoma.5 Alguacil-Garcia et al. divided anaplastic pancreatic carcinomas into four subsets: (1) spindle cell (2) osteoclastic giant cell (3) pleomorphic giant cell, and (4) round cell anaplastic.3 It remains challenging to classify individual cases into one of these categories, as many demonstrate a spectrum of histopathologic features. In contrast to database reviews that rely on inconsistent pathologic classification, our study features a single expert pathologist’s review of samples at a high-volume institution. Our definition for this case series of SCP is most consistent with the aforementioned spindle cell carcinoma: a predominance of sarcomatous cellularity, diffuse prolfiertion of atypical spindle shaped cells, and presumed epithelial derivation. This histopathologic diagnosis was appreciated both with (Fig. 1) and without (Fig. 2) OCGC.

Fig. 1 –

Presence of osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells in background of anaplastic and spindle cells. (Colorversion of figure is available online.)

Fig. 2 –

Sarcomatoid carcinoma with poorly differentiated anaplastic, pleomorphic cells with spindle cell component. (Color version of figure is available online.)

SCP remains rarely described and poorly understood, yet the majority of existing case reports convey a survival worse than that of ductal adenocarcinoma with many succumbing to early metastasis2,9–11 (Table 3). However, previously published reports often inappropriately included carcinosarcoma in their reviews of SCP. Carcinosarcoma is an epithelial malignancy with distinct biphasic components of epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. It is theorized these subparts are from a monoclonal origin with either metaplastic conversion of one type to the other or separate downstream differentiation from a single stem cell.14,15 SCP represents poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with a spindle cell background, without the distinct components of mesenchymal sarcoma and is thus a unique diagnosis from carcinosarcoma.

Table 3 –

Review of clinicopathologic outcomes of patients with sarcomatoid carcinoma of the pancreas reported in literature.

| Author, year | Sex, age | Size (cm) | LN status | LVI/PNI | Presence of OCGC | Survival | Recurrence pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higashi et al., 199911 | M, 74 | 4.5 | 0/NR | Y/Y | N | 3 mo | Carcinomatosis |

| Uenishi et al., 199910 | M, 56 | 11 | NR | NR | NR | 2 mo | Hepatic |

| De la Riva et al., 200612 | F, 72 | NR | NR | NR | N | 9 mo | Carcinomatosis |

| Kane et al., 20142 | M, 85 | 3.5 | Y | N/Y | N | 26 mo-elive* | None |

| Abe et al., 20169 | F, 74 | 12 | NR | NR | NR | 8 mo | NR |

F = female; M = male; N = no; Y = yes; LVI = lymphovascular invasion; PNI = perineural invasion; OCGC = osteoglastic like giant cells; m* = months; NR = not recorded/unknown; LN = lymph node.

Living patient.

Review of our institution’s data confirms the notion that a large proportion of individualswill succumb to early metastatic disease. However, long-term survival after resection for SCP, although still poor, occurs with a similar frequency as ductal adenocarcinoma. Long-term survival after resection for SCP is not unique to our series, with a case of 26-month disease-free survival also reported.2 A diagnosis of sarcomatoid features may not necessarily portend to a uniformly dismal prognosis and still offers a chance for cure with optimal treatment.

Long-term survival after resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma approaches 20%.16–18 In this disease, the prognostic histopathologic factors include tumor grade, receipt of adjuvant therapy, R0 resection margin, and lymph node status.16–18 Owing to the rarity of the SCP diagnosis, we lack statistical power for comparative analysis of these carcinosarcoma.factors. Nevertheless, the two long-term survivors in our series both underwent R0 resections and received adjuvant therapy. These subjects underwent different operations to achieve R0 status. One patient underwent a distal pancreatectomy. The other patient required pancreaticoduodenectomy with subtotal gastrectomy due to large tumor size. Of note, the two patients (25%) who did not undergo complete R0 tumor extirpation both had early recurrence leading to their mortality in <3 months (Table 2).

OCGCs are multinucleated giant cells with abundant cytoplasm that resemble giant cell tumors of the bone. They can occasionally be found interspersed within the stroma of anaplastic tumors.19 Their etiology and pathologic significance remains debated. The presence of OCGC has previously been reported to offer a protective effect in anaplastic carcinoma with 5-year survival reported in some studies in up to 50% of patients.6,20 In other small case series, there is no improvement in this subtype,21,22 and some suggest a worse prognosis.23 The presence or absence of OCGC helps to define two different subclasses of anaplastic pancreatic carcinoma in the current WHO classification system.5 Final histopathologic classification is also impacted by the wide variety in appearance of the background stroma in each specimen. In this series of SCP, we identified two cases with OCGCs. One of these patients succumbed to early mortality. The remaining patient has not had adequate follow-up to determine survival.

One strategy for identifying patients with disease biology amenable to long-term survival might include increased utilization of neoadjuvant therapy in resectable patients. There are several challenges that remain before this approach can be routinely recommended. First, it is challenging to discern the SCP subtype from other pancreatic neoplasia on imaging. Previous reports have suggested anaplastic pancreatic carcinomas to be represented on CT imaging as large, hypodense tumors often cystic in appearance with central necrosis and wall enhancement during the venous phase.20 Some of these features were present in our series; however, no definitive characteristics were consistently noted. Similarly, definitive diagnosis of SCP is challenging from biopsy specimens obtained during endoscopy. Although preoperative tissue diagnoses of SCP or OCGC has been reported from EUS and FNA,12,19 typical findings are less specific.12,20 This was consistent within our population, as preoperative biopsy failed to distinctly identify SCP in all cases. Finally, the benefit of cytotoxic systemic therapy or radiotherapy remains unclear in this disease. Integrating these considerations, the use of neoadjuvant therapy in the setting of SCP remains uncertain and neither long-term survivor in our series underwent neoadjuvant treatment. Both, however, did receive adjuvant treatment with either radiation or chemoradiation therapy.

There are multiple limitations of this study. SCP is a rare diagnosis along a spectrum of diseases with similar histopathologic appearance. The small size of our population provides a challenge for appropriate evaluation of this cohort. Although similar to reports in existing literature, multiple patients in our series were deceased within a 90-day perioperative period. These individuals were discharged from index admission and in many cases had documented metastasis, but remain a study limitation due to the close proximity of major surgery. In addition, the follow-up limits the data available as well as the associated biases with the conduct of retrospective chart reviews. Multi-institutional collaboration with expert pathology review of possible SCP cases may identify more cases and provide improved power to better describe the factors associated with long-term survival.

Conclusions

SCP is a rarely described subset of pancreatic malignancy that exhibits bimodal outcomes following resection. Current literature conveys a nihilistic attitude with a prognosis worse than standard PDA. Although many patients have rapid disease recurrence leading to their early demise, a diagnosis of SCP does not necessarily portend to a uniformly dismal prognosis following complete tumor resection. Long-term survival was achieved in 25% in our series, similar to the survival rates of PDA. The use of multidisciplinary treatment modalities should be considered for these individuals in a curative paradigm of disease management. The optimal multidisciplinary treatment for this disease is not known. Further research is needed to improve preoperative diagnosis and to define the cohort of individuals with potential for longterm survival; therefore, aggressive therapies may be tailored appropriately in this patient subset.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to show their gratitude to Elizabeth Thompson MD, PhD for assistance with pathologic review of identified sarcomatoid carcinoma cases. This work was supported by NCI T32 grant 5T32CA126607 for A.B.B.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health T32 Grant for AB. This abstract was selected for quick shot presentation at 2017 Academic Surgical Congress in Las Vegas, NV.

Footnotes

Disclosure

These authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

R E F E R E N C E S

- 1.Cancer facts & figures 2016. Atlanta, GA: A.C. Society; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane JR, Laskin WB, Matkowskyj AK, Villa C, Yeldandi AV. Sarcomatoid (spindle cell) carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:245–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alguacil-Garcia A, Weiland LH. The histologic spectrum, prognosis, and histogenesis of the sarcomatoid carcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer. 1977;39:1181–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paal E, Thompson LD, Frommelt RA, Przygodzki RM, Heffess CS. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 35 anaplastic carcinomas of the pancreas with a review of the literature. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2001;5:129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosman F, Carneiro F, Hruban R. WHO Classification of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon, France: World Health Organization IARC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark CJ, Graham RP, Arun JS, Harmsen WS, Reid-Lombardo KM. Clinical outcomes for anaplastic pancreatic cancer: a population-based study. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer of the head of the pancreas. 201 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;221:721–731. discussion 731–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He J, Ahuja N, Makary MA, et al. 2564 resected periampullary adenocarcinomas at a single institution: trends over three decades. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abe T, Amano H, Hanada K, et al. A spindle cell anaplastic pancreatic carcinoma with rhabdoid features following curative resection. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;5:327–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uenishi T, Hirohashi K, Kubo S, et al. A pancreatic anaplastic carcinomaofspindle-cellform.IntJPancreatol.1999;26:201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higashi M, Takao S, Sato E. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report with immunohistochemical study. Pathol Int. 1999;49:453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De la Riva S, Munoz-Navas MA, Betes M, Subtil JC, Carretero C, Sola JJ. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the pancreas and congenital choledochal cyst. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:1005e1006. discussion 1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oymaci E, Argon A, Coskun A, et al. Pancreatic carcinosarcoma: case report of a rare type of pancreatic neoplasia. JOP. 2013;14:212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HS, Joo SH, Yang DM, Lee SH, Choi SH, Lim SJ. Carcinosarcoma of the pancreas: a unique case with emphasis on metaplastic transformation and the presence of undifferentiated pleomorphic high-grade sarcoma. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron JL, He J. Two thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA, et al. One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann Surg. 2006;244:10–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serrano PE, Cleary SP, Dhani N, et al. Improved long-term outcomes after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a comparison. between two time periods. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1160–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore JC, Hilden K, Bentz JS, Pearson RK, Adler DG. Osteoclastic and pleomorphic giant cell tumors of the pancreas diagnosed via EUS-guided FNA: unique clinical, endoscopic, and pathologic findings in a series of 5 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strobel O, Hartwig W, Bergmann F, et al. Anaplastic pancreatic cancer: presentation, surgical management, and outcome. Surgery. 2011;149:200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singhal A, Shrago SS, Li SF, Huang Y, Kohli V. Giant cell tumor of the pancreas: a pathological diagnosis with poor prognosis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010;9:433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leighton CC, Shum DT. Osteoclastic giant cell tumor of the pancreas: case report and literature review. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24:77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jo S Huge undifferentiated carcinoma of the pancreas with osteoclast-like giant cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2725–2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]