Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether baseline social participation modifies the effect of a long-term structured physical activity (PA) program on major mobility disability (MMD).

Methods

1,635 sedentary adults (70–89 years) with physical limitations were randomized to either a structured PA or health education (HE) intervention. Social participation was defined categorically at baseline. High social participation was defined as attending organized group functions at least once per week and visiting with noncohabitating friends and family ≥7 hr per week. Anything less was considered limited social participation. Participants performed a standardized walking test at baseline and every 6 months for up to 42 months. MMD was defined as the loss in the ability to walk 400 m.

Results

There was a significant intervention by social participation interaction (p = .003). Among individuals with high levels of social participation, those randomized to PA had significantly lower incidence of MMD (hazard ratio [HR], 0.43 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.27–0.68]; p < .01) than those randomized to HE. Individuals with limited social participation showed no mobility benefit of the PA intervention when compared with their HE counterparts (HR, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.77–1.11]; p = .40).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that baseline social participation is an important factor for the success of a PA intervention aimed at delaying mobility disability.

Keywords: Disability, Physical activity, Social integration

Reduced mobility is a common characteristic among older adults that is associated with increased disability, morbidity, hospitalization, and mortality (Newman et al., 2006). To date, structured physical activity (PA) remains the only definitive intervention shown to delay the onset of mobility disability among this population (Pahor et al., 2014). However, a considerable margin of variability in response still exists. In attempt to understand this variability, it is imperative that potential effect modifiers that explain the differential response to a structured PA program are studied.

Social participation is one potential factor that may explain the variability in response to a structured PA intervention. The term social participation describes the frequency and duration of social interaction with persons other than a spouse (Utz, Carr, Nesse, & Wortman, 2002). Previous literature suggests that it is likely reflective of a personal desire to interact with others (Gow, Corley, Starr, & Deary, 2013). The conceptualization of social participation may be similar to other commonly interchanged terms (e.g., social engagement, community engagement, community participation), yet it is distinguishably different from others (e.g., social support, social network, social integration) depending on how their definition falls into a previously proposed taxonomy of social activities (Levasseur, Richard, Gauvin, & Raymond, 2010). Among the many definitions of social participation found in the literature, the underlying principle is to obtain measurement of an individual’s involvement in activities that provide interaction with other members of society or the community in both a formal and informal context—two statistically and conceptually distinct dimensions. Therefore, an assessment of social participation can be achieved through assessment of frequency and duration of contact with friends and family, and frequency of participation in civic organizations (Levasseur et al., 2010).

Previous research has shown that low levels of social participation are associated with an increased risk in physical inactivity (Kim, Subramanian, Gortmaker, & Kawachi, 2006), mobility impairment (Avlund, Lund, Holstein, & Due, 2004), and mortality (Levasseur et al., 2010). As the transition to older adulthood naturally leads to reductions in both physical function and social participation, there is likely a reciprocal exacerbating relationship between them (Mendes de Leon, Glass, & Berkman, 2003). In fact, since previous longitudinal studies have shown that high levels of social participation are associated with higher amounts of PA (Kaplan, Lazarus, Cohen, & Leu, 1991) and better mobility (Sorensen, Axelsen, & Avlund, 2002), it is plausible that social participation may enhance the effect that PA has on mobility.

Although previous research supports high levels of social participation being beneficial to mobility, the exact mechanism underlying this effect remains unclear (Mendes de Leon et al., 2003). One possible explanation may be related to Festinger’s Social Comparison Theory that suggests that individuals self-enhance by comparing themselves to others (Festinger, 1954). In our application of this theory, individuals with high levels of social participation may be more prone to engage in social comparison (both upward and downward) that in the context of meaningful social involvement is positively interpreted, thus providing a sense of purpose and control in life and efficacy in abilities that relate to disablement (Mendes de Leon et al., 2003). In other words, in a group-based program with measured goals or positive achievements, being more prone to social interaction may have a positive effect through downward comparison to others who are worse off and unable to reach the desired goal (“I’m better off than this person”), or through upward comparison to others who are better off and achieving the desired goal (“I’m as good as this person” or “I’m going to be as good as this person”) (Taylor & Lobel, 1989). In older adults, this positive effect would manifest itself as an enhanced sense of control and self-efficacy that is known to mitigate the impact of age-related changes in physical health on daily function and disability (Seeman, Unger, McAvay, & Mendes de Leon, 1999). For example, Mullen and colleagues found that older adults with higher walking-related self-efficacy demonstrated better lower-extremity function and fewer lower-body functional limitations (Mullen, McAuley, Satariano, Kealey, & Prohaska, 2012). In the context of PA, self-efficacy is known to increase independent of social participation (McAuley, Lox, & Duncan, 1993) and appears to mediate the positive effects by further enhancing the improvement in physical function (McAuley et al., 2007). A previous intervention designed to specifically target self-efficacy through social support yielded results consistent to this idea, however, the analyses considered no objective measure of social participation (Brawley, Rejeski, Gaukstern, & Ambrosius, 2012). In addition, it should be noted that most PA programs are behaviorally designed to promote group cohesiveness through socialization as a result of group exercise being more effective in achieving desired physiological (e.g., blood pressure, lipoproteins) and functional (e.g., gait speed, balance) health outcomes than exercising alone. With the rational assumption that individuals who engage in more social activity are more prone to social cohesion, then perhaps the most social individuals would experience the greatest desired effect in a group exercise setting (Burke, Carron, Eys, Ntoumanis, & Estabrooks, 2006). These findings suggest that the combination of high levels of social participation and induced self-efficacy by a PA program could have a greater impact on reducing disability in older adults. However, certain program design features with underlying social drivers such as the inclusion or absence of health-related goals may cause the potentially positive interaction on mobility disability referenced in the literature to behave differently (de Vries et al., 2012).

In a group-based program with specific health goals and known benefits (e.g., walking minutes per day, sessions per week), high social participation may provide benefit through conversation focused on positive affirmation of the intervention (Kampfe, 2015). For example, in a walking program where participants are instructed to meet specific weekly goals, participants with high social participation may be more inclined to interact with other participants and discuss the success of achieving their goals and expected health benefits. This positive interpretation of social comparison could exist through both upward comparison that serves to increase motivation or hope, and downward comparison that serves to ameliorate self-esteem and may ultimately result in a heightened sense of purpose and belonging (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001; Taylor & Lobel, 1989). In contrast, high social participation may have less impact in a group-based program without these goals, such as health education (HE) seminars (Horhota, Stroup, & Price, 2013). In these situations, it is possible that individuals compare themselves to others and evaluate themselves in a social context that may be either demotivating or distracting. Perhaps, in the absence of specific goals, individuals with high levels of social participation attending HE seminars may be more prone to discuss their health problems in a negative way through upward comparison to others who are better off (“I’m worse than this person”), or through downward comparison to others with more and/or further progressed health problems (“I’m going to end up like this person”) (Taylor & Lobel, 1989). This negative interpretation of social comparison may result in participants having a negative sense of their future course (Beaton, Tarasuk, Katz, Wright, & Bombardier, 2001). Regardless of the mechanism driving the effect within a HE program, the interesting question is whether everyone in a PA program benefits from the social context of group-based PA or whether social participation operates as an individual difference variable and moderates the effect of the intervention on mobility. In this context and throughout the entirety of this paper, we will view individuals with high social participation as having an innate propensity (i.e., trait) to initiate conversation with others and thereby elicit more positive feedback on their program participation (Levasseur et al., 2010).

The objective of this study was to investigate whether baseline social participation modifies the effect of a long-term structured PA program or, for comparative purposes, a HE program on major mobility disability (MMD). Essentially, we argue that high social participation in a structured PA program leads to a greater affinity to discuss the positive effects of the intervention, which in turn leads to positively interpreted social comparison that reinforces self-efficacy and mitigates the impact of age-related changes in health. While it is already established that a structured PA program is associated with a reduced risk of MMD compared to a successful aging HE intervention (Pahor et al., 2014), we hypothesize that this effect will be greater for participants engaged in high levels of social participation compared to those with limited levels of social participation. The results from this study will provide insight on the role of social participation on the potential benefits of PA interventions for preventing mobility disability among older adults.

Methods

The present study is a secondary analysis of data from the LIFE study—a Phase III, multicenter, randomized controlled trial designed to assess the treatment efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of a long-term moderate-intensity PA program compared to a successful aging HE program. The LIFE study methods have been previously described in detail (Pahor et al., 2014).

Study Participants

Participants were recruited regionally from eight field sites participating in the LIFE study (University of Florida, Gainesville, FL; Northwestern University, Chicago, IL; Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA; IL; University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; Tufts University, Boston, MA; Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC; and Yale University, New Haven, CT). Targeted community mailing was the primary recruitment strategy with a total of 14,831 individuals that were screened for eligibility. Eligibility criteria included age (70–89 years), summary score < 10 on the EPESE short physical performance battery (SPPB) (Guralnik, 1995), sedentary lifestyle, ability to walk 400 m unassisted, and a Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MSE) score of no more than 1.5 SD below education- and race-specific norms. The ability to walk 400 m unassisted is considered an excellent proxy for community ambulation that can be used to identify individuals more likely to remain active in the community. Screening, recruitment yields, and baseline characteristics have been previously described in detail (Pahor et al., 2014).

After screening, 1,635 men and women (78.9 ± 5.2 years) who were at high risk for MMD (SPPB score = 7.4 ± 1.6) were randomized at baseline to receive either a PA or HE intervention. Participants performed a standardized walking test (400-m walk test) at baseline and follow-up clinic visits (every 6 months, over 42 months).

Social Participation

There is a variety of definitions to quantify the degree of social participation in older adults (Levasseur et al., 2010). For this study, we chose a multidimensional construct that incorporates both formal and informal interactions that is consistent with several other studies (Donnelly & Hinterlong, 2010; Nilsson, Avlund, & Lund, 2011; Utz et al., 2002; Zettel-Watson & Britton, 2008). All components of this definition were specific to a 4-week recall period and obtained through five questions taken from the Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors (CHAMPS) questionnaire (Stewart et al., 2001). Formal components included frequency (number of times per week in a typical week during the past 4 weeks) and duration (number of total hours per week in a typical week during the past 4 weeks) of attending organized group functions: senior center, volunteer work, church or church activities, or other club or group meetings. Informal components included frequency and duration (both same as formal) of visitation with friends and family (other than those who share habitation).

The primary predictor of social participation was analyzed in two ways. First, a continuous score was created ranging from 0 to 1170 points to reflect the total number of minutes of social participation per typical week. The total minutes spent in informal and formal components were summed according to the following (as a median of the hour span): No = 0 min, < 1 hr = 30 min, 1–2.5 hr = 105 min, 3–4.5 hr = 225 min, 5–6.5 hr = 345 min, 7–8.5 hr = 465 min, and ≥9 hr = 585 min. Since formal social participation was assessed across four activities, we calculated it as an average to weight it similarly when combining it with informal social participation.

A categorical variable was created by assigning one point for performing one or more formal activities at least once per week and one point for attaining cumulative informal activity of ≥7 hr in a typical week. Table 1 summarizes the breakdown of the social participation categories. Those without any formal or informal social participation were assigned a score of zero. A score of 2 points represented an individual with higher levels of both formal and informal social participation and was the highest 20th percentile of the sample. The decision to label these individuals as having “high social participation” and those with 1 or less points as having “limited social participation” was based on two population-based statistics: First, the 2014 American Time Use Survey reported that older adults spend approximately 5 hr per week socializing and communicating with friends (US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014). Thus, individuals with a positive affirmation of spending ≥7 hr in a typical week visiting with friends and family would be considered to have high levels of social participation compared to the national average. Second, the Cornell National Social Survey showed that a majority (64%) of older adults are actively involved in social groups (Survey Research Institute, Cornell University, 2014). Since they would be in the minority, those not participating in formal social groups were labeled as having limited social participation. We also report results from sensitivity analyses where we derived more and less conservative ways to categorize high social participation.

Table 1.

The Social Participation Score Across Social Participation and Intervention Groups

| Characteristics, number (%) | Health education | p value | Physical activity | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High social participation (n = 112) | Limited social participation (n = 705) | High social participation (n = 126) | Limited social participation (n = 692) | |||

| Continuous score mean (SD) | 633.2 (103.3) | 217.1 (157.4) | <.0001* | 650.6 (97.5) | 206.1 (156.9) | <.0001* |

| Visit ≥7 hr | 112 (100) | 39 (5.5) | <.0001* | 126 (100) | 39 (5.6) | <.0001* |

| Senior center | 14 (12.5) | 68 (9.6) | .36 | 16 (12.7) | 63 (9.1) | .21 |

| Volunteer | 39 (34.8) | 165 (23.4) | .01* | 49 (38.9) | 128 (18.5) | <.0001* |

| Church | 84 (75.0) | 405 (57.4) | .0004* | 96 (76.2) | 380 (54.9) | <.0001* |

| Clubs | 39 (34.8) | 148 (21.0) | <.0001* | 51 (40.5) | 117 (16.9) | <.0001* |

Note: Results show differences between high and limited social participation groups within intervention arms.

*p < .05.

Interventions

Participants were randomized at baseline to either a HE or PA intervention. The average length of participation was 2.6 years. A behavioral change approach was used in both interventions integrating social cognitive theory principles along with group-mediated counseling in the promotion of PA among older adults (Rejeski et al., 2003). The early phase of the intervention also used elements derived from the transtheoretical model to supplement this approach (e.g., preparation and action phases included consciousness raising, building of self-efficacy, informational exchange, and other cognitive approaches). The later phases were supplemented with ongoing reinforcement, social support, and related behavioral approaches. All approaches were provided through individually tailored social problem-solving strategies. All participants were provided an initial 45-min face-to-face information session with a LIFE study member where details of the interventions, including expectations, were explained in-depth. There were no specific directions given to either encourage or discourage social interaction among participants for either intervention. The HE intervention was designed to provide attention and HE and typically consisted of small groups of 10–20 individuals. Participants attended supervised center-based sessions on a weekly basis for the first 26 weeks, transitioning to monthly sessions thereafter. Seminars were given on a variety of health topics related to older adults, including nutrition, health care system navigation, travel safety, medication use, foot care, preventive medicine and where to go for reliable health information. Seminars did not include topics on PA. However, participants did receive basic information about PA participation at randomization. Each session also included a 5–10 min instructor-led program of upper extremity flexibility exercises. Program adherence was reinforced through regular telephone contact with the participants.

The PA intervention typically consisted of smaller groups of 5–10 individuals and included walking, strength, flexibility, and balance training with a required attendance of two center-based visits per week. Additional home-based activity session were also incorporated in the interventions starting with one per week during weeks 1–4, two per week during weeks 4–8, and three to four per week from week 9 until the end of the study. Participants were asked to walk using ratings of perceived exertion (RPE), a common self-regulation tool, as a method to maintain a moderate intensity (Borg RPE of 13) at least 5 days per week for a minimum 150 min per week (Borg, 1988). The supervised center-based PA sessions were individualized and progressed toward a goal of 30 min of walking, 10 min of lower extremity strength training (ankle weights; 2 sets of 10 repetitions; Borg RPE of 15–16), 10 min of balance training, and large muscle group flexibility exercises done at each session. The intervention started with lighter intensity exercises and gradually progressed in intensity over the first 2 to 3 weeks to ensure the safety and effectiveness of the PA intervention.

Participants of each intervention were categorized by social participation score as follows: PA—high social participation (n = 126), PA—limited social participation (n = 692), HE—high social participation (n = 112), and HE—limited social participation (n = 705).

Outcomes

MMD was defined as the inability to complete a 400-m walk test within 15 min without sitting, receiving help from another person, or using assistive device (with the exception of canes). Participants were asked to walk 10 laps of a 20-m course (40-m/lap) at their usual pace being permitted to stop and rest if necessary but not permitted to sit. If MMD could not be objectively measured, an alternative objective method of assessment was used based on the inability to walk 4 m in less than 10 s. If objective assessment was unobtainable, a final method of assessment was used based on self-, proxy-, or medical record-reported inability to walk across a room. Persistent MMD was defined as two consecutive assessments of MMD or MMD being followed by death. Censoring was defined as the time to last follow-up assessment for MMD.

Adherence

Adherence was assessed through attendance records taken at the supervised center-based sessions for both interventions. Adherence to the PA intervention was also assessed at baseline and follow-up using objective and subjective measures. Adherence was objectively measured through a hip-worn accelerometer, a sensor that measures body movements, over 7-day periods until 24 months follow-up using a definition of 760 or more counts per minute for moderate activity (Matthew, 2005). Subjective measurement of adherence was done until 36 months follow-up using self-reported minutes of walking and performing weight-training activities using the CHAMPS questionnaire.

Data Analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarized by intervention arm (PA vs. HE) within each social participation group and were compared using ANOVA for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. To test for a modification effect, comparing the between interventions effect by social participation group provides a reasonable approach to maintain randomization. Intervention attendance, self-reported minutes in walking and weight training activities (CHAMPS), and accelerometer-determined time spent at ≥760 counts per minute were analyzed using mixed-effects analysis of covariance models for repeatedly measured outcomes. Models contained the following terms: field center and sex (both used to stratify randomization), baseline value of the relevant PA measure, clinic visit, intervention, social participation, intervention by social participation interaction, intervention by clinic visit interaction, social participation by clinic visit interaction, and intervention by social participation by clinic visit interaction. Least square means were used to estimate the mean minutes of activity (by either CHAMPS or accelerometry) for each intervention arm by social participation status at each visit. Contrasts were used to estimate the mean difference in minutes of activity between the two intervention groups by social participation status.

The effect of the intervention on the primary outcome of MMD (i.e., time until the initial ascertainment of MMD) was tested using Cox regression models based on a two-tailed significance level of 0.05 using the intention-to-treat approach. A second model included additional covariates of race, systolic blood pressure, depression, education, comorbidity, obesity, and cognition—variables known to be associated with social participation or significantly different between intervention groups within social participation group. Adjustments were made for main effects of the covariates as well as covariate by arm interactions—a recommended approach for adjustment of confounding in subgroup analyses. The effect of social participation was examined two ways. The first used the continuous and the second used the dichotomized (high vs. limited) version of social participation. We also assessed whether the Cox regression models satisfied the proportional hazard assumption by testing the group by event time interaction. The potential moderating effect of baseline social participation of LIFE interventions was examined by formally testing the intervention by social participation interaction using Wald chi-square tests. Field center and sex were used as stratification factors in all models. The proportion of event-free participants—those who never failed the 400-m walk test during the follow-up—was described using Kaplan–Meier estimates. 400-m walk test failure time was measured from the time of randomization; follow-up was censored at the last successfully completed 400-m walk test. Time until the first occurrence of persistent MMD was analyzed similarly. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Detailed comparisons showing intervention group similarity at baseline have been described previously (Pahor et al., 2014). The scoring summary for social participation components by group (high vs. limited) within each arm of the intervention is presented in Table 1. We found the division of scores adequately represented the social participation categories created based on the national sample of older adults (Nimrod, Janke, & Kleibe, 2008). The continuous social participation scores were significantly higher among the high social participation groups compared to the limited social participation groups in each arm of the intervention (p < .01). As per the high social participation requirement of visiting with friends and family for 7 or more hours per week, both the PA and HE high social participation group had 100% fulfillment compared to their PA and HE limited social participation counterparts who only had 5.6% and 5.5% fulfillment, respectively. Attendance of all organized group functions were reported at significantly higher frequency (p < .01) among high social participation groups compared to low social participation groups within each arm of the intervention with the exception of visiting the senior center. Table 2 summarizes the baseline characteristics between each arm of the intervention for each social participation group. Baseline characteristics were still reasonably balanced between the randomization groups within the subgroups. At baseline, the PA high social participation group had 14.0% fewer non-Whites and 12.3% lower systolic blood pressure scores than the HE high social participation group. Also at baseline, the PA limited social participation group had 4.7% fewer individuals with depression scores than the HE limited social participation group. There were no differences in age, BMI, or SPPB scores between intervention arms for either social participation group.

Table 2.

Baseline Participant Characteristics

| Characteristics, number (%) | High social participation | p value | Limited social participation | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health education (n = 112) | Physical activity (n = 126) | Health education (n = 705) | Physical activity (n = 692) | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 78.7 (5.7) | 78.8 (5.3) | .95 | 79.1 (5.2) | 78.7 (5.2) | .10 |

| Women | 80 (71.4) | 92 (73.0) | .78 | 471 (66.8) | 455 (65.8) | .68 |

| Caucasian | 101 (90.2) | 96 (76.2) | .004* | 559 (79.7) | 529 (76.8) | .18 |

| Married | 38 (34.2) | 35 (28.0) | .30 | 250 (35.7) | 260 (37.7) | .45 |

| High school or less education | 32 (28.8) | 45 (35.7) | .09 | 231 (32.9) | 228 (33.0) | 1.00 |

| Smoke | 3 (2.8) | 3 (2.4) | .86 | 21 (3.0) | 23 (3.4) | .73 |

| Obese | 58 (51.8) | 66 (52.4) | .21 | 66 (52.4) | 308 (44.5) | .10 |

| Fair/poor health | 26 (23.4) | 22 (17.6) | .27 | 114 (16.2) | 109 (15.8) | .81 |

| Elevated systolic blood pressure | 100 (89.3) | 97 (77.0) | .012* | 535 (76.1) | 547 (79.0) | .19 |

| Comorbidity | 16 (14.3) | 22 (17.5) | .34 | 112 (15.9) | 97 (14.0) | .61 |

| Low cognition | 28 (25.0) | 29 (23.0) | .72 | 233 (33.0) | 232 (33.5) | .85 |

| Poor physical performance | 52 (46.4) | 50 (39.7) | .29 | 326 (46.2) | 303 (43.8) | .36 |

| Slow gait speed | 58 (51.8) | 56 (44.4) | .26 | 306 (43.4) | 292 (42.2) | .65 |

| Depression | 11 (10.2) | 13 (10.7) | .91 | 131 (19.6) | 98 (14.9) | .024* |

| Accelerometry of moderate intensity activity, mean (SD), min/week | 206.9 (198.3) | 199.9 (161.7) | .79 | 193.0 (179.4) | 189.3 (154.7) | .71 |

| Self-reported walking/strength training activities, mean (SD), min/week | 87.6 (131.2) | 84.9 (145.3) | .88 | 86.5 (135.0) | 73.4 (121.8) | .056 |

| Self-reported moderate intensity exercise, mean (SD), min/week | 40.3 (90.0) | 58.0 (141.8) | .26 | 44.3 (102.2) | 46.6 (115.0) | .69 |

| Self-reported all exercise, mean (SD), min/ week | 575.6 (429.7) | 553.3 (407.1) | .68 | 480.0 (364.9) | 461.3 (354.8) | .33 |

Note: Obese was defined as body mass index ≥ 30; fair/poor health was self-perceived/self-reported; elevated systolic blood pressure was defined as > 150 mmHg; comorbidity was defined as the presence of ≥ 2 chronic diseases; low cognition was defined as a Modified Mini-Mental State Exam score < 90; poor physical performance was defined as Short Physical Performance Battery score ≤ 7; slow gait speed was defined as a 400-m walk test completion time of < 0.8 m/s; depression was defined as a Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale score ≥ 16; accelerometry of moderate intensity activity was based on the cut point of ≥ 760 counts per min. Results show differences between high and limited social participation groups within intervention arm.

*p < .05.

Intervention Adherence

The group attendances of scheduled sessions were 63% and 73% for the PA and HE groups, respectively, with similarity across social participation groups (PA: 62% high vs. 64% limited; HE: 71% high vs. 73% limited). Predicted values from mixed-effects analysis of covariance for objective and subjective measures of intervention adherence for high and limited social participation groups within each arm of the intervention are illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1. Based on CHAMPS questionnaire responses, over the initial 24-month intervention period the PA high social participation group maintained an average of 215.1 min/week in walking and weight training activities with a similar amount seen in the PA limited social participation group (209.5 min/week). The HE high social participation group reported 121.7 min/week that was similar to the HE low social participation group (122.1 min/week). Average increase from baseline was 130.2 min/week for the PA high social participation group that was similar to the increase seen in the PA limited social participation group (136.1 min/week). The HE groups showed small and similar increases (34.1 min/week for the HE high social participation group and 35.5 min/week for the HE limited social participation group). Objectively measured PA assessed with accelerometry demonstrated similar effects between groups, where the PA high social participation group had an average of 210.9 min/week compared to the HE high social participation group at 168.8 min/week. The PA limited social participation group had a similar level of moderate intensity activity with 205.3 min/week that was significantly higher than the HE limited social participation group at 168.7 min/week. Average change from baseline was 12.0 min/week for the PA high social participation group that was similar to changes seen in the PA limited social participation group (15.4 min/week). For both HE groups, the average change from baseline was negative (−29.7 min/week for the HE high social participation group and −22.7 min/week for the HE limited social participation group).

MMD

A total of 794 participants in the PA group and 803 participants in the HE group completed the 400-m walk test, making MMD data available for 97.1% and 98.3% of participants in each group, respectively. Prior to the last planned follow-up visit, 49 individuals (6.0%) were censored within the PA group along with 55 individuals (6.7%) in the HE group. The reported annual loss to follow-up was 4.0%. Table 3 shows details about the event rates of MMD and persistent MMD for both high and limited social participation groups within each intervention arm in addition to the interventions overall.

Table 3.

Major Mobility Disability Outcome Summary Statistics

| Participation | Events (number) | Health education | Physical activity | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total participants | Rate | Rate % | Events (number) | Total participants | Rate | Rate % | ||||

| High | 52 | 112 | 0.46 | 21.7 | 27 | 126 | 0.21 | 9.2 | 0.50 (0.29–0.88) | 0.50 (0.28–0.88) |

| Limited | 238 | 705 | 0.34 | 15.5 | 219 | 692 | 0.32 | 14.3 | 0.88 (0.64–1.21) | 0.89 (0.63–1.24) |

| Total | 290 | 817 | 0.35 | 16.3 | 246 | 818 | 0.30 | 13.5 | 0.82 (0.69–0.98)* | 0.82 (0.69–0.98)* |

| High | 26 | 112 | 0.23 | 10.6 | 12 | 126 | 0.10 | 3.9 | 0.52 (0.23–1.16) | 0.52 (0.23–1.18) |

| Limited | 136 | 705 | 0.19 | 8.6 | 108 | 692 | 0.16 | 6.9 | 0.92 (0.61–1.39) | 0.89 (0.57–1.38) |

| Total | 162 | 817 | 0.20 | 8.8 | 120 | 818 | 0.15 | 6.4 | 0.72 (0.57–0.91)* | 0.72 (0.57–0.91)* |

Note: Event and rate refer to number and percent of individuals who were unable to complete a 400-m walk test within 15 min without sitting, receiving help from another person, or using assistive device (with the exception of canes). Rate % refers to the rate per 100 person years. Adjusted analyses included the following covariates: comorbidity, obesity, cognition, systolic blood pressure, race, depression, and education. Hazard ratios reported for total (overall between intervention effect) are from the previous report of Pahor et al. 2014.

*p < .05.

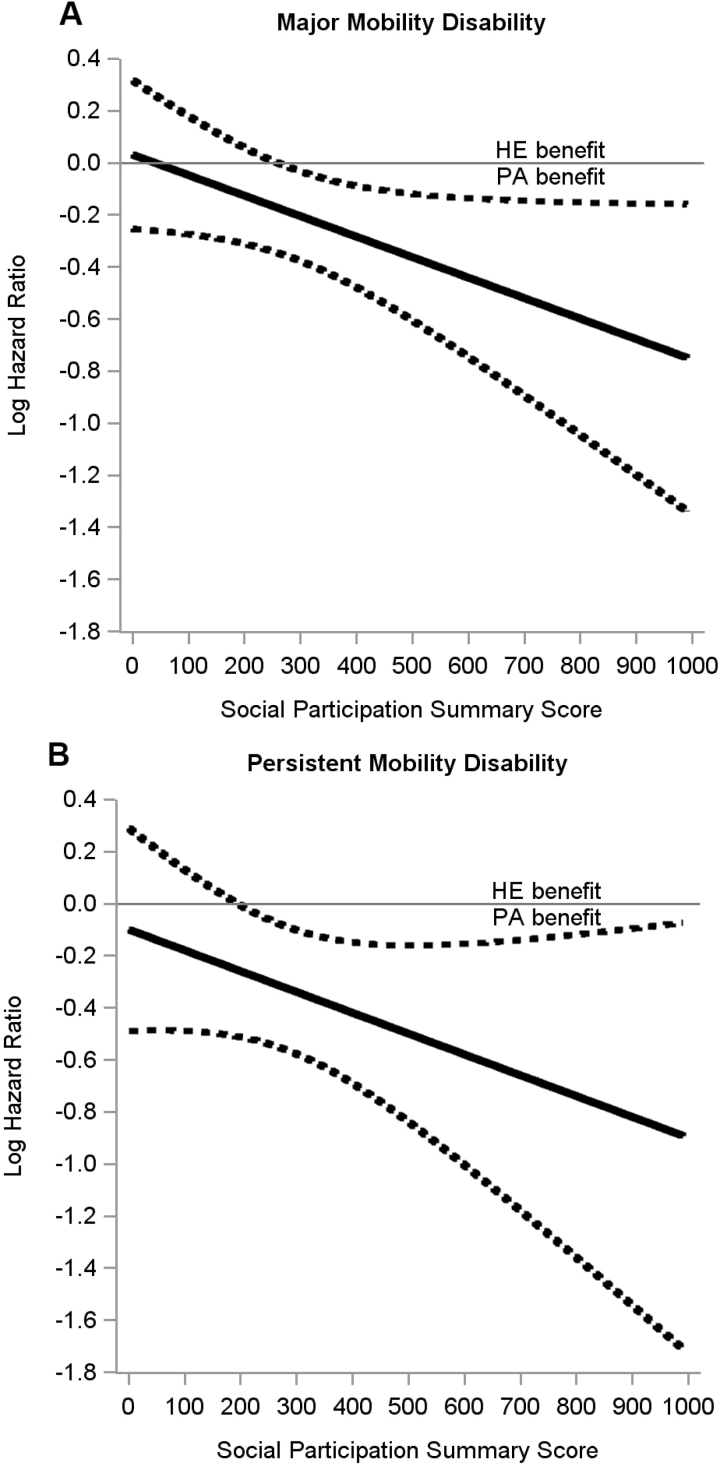

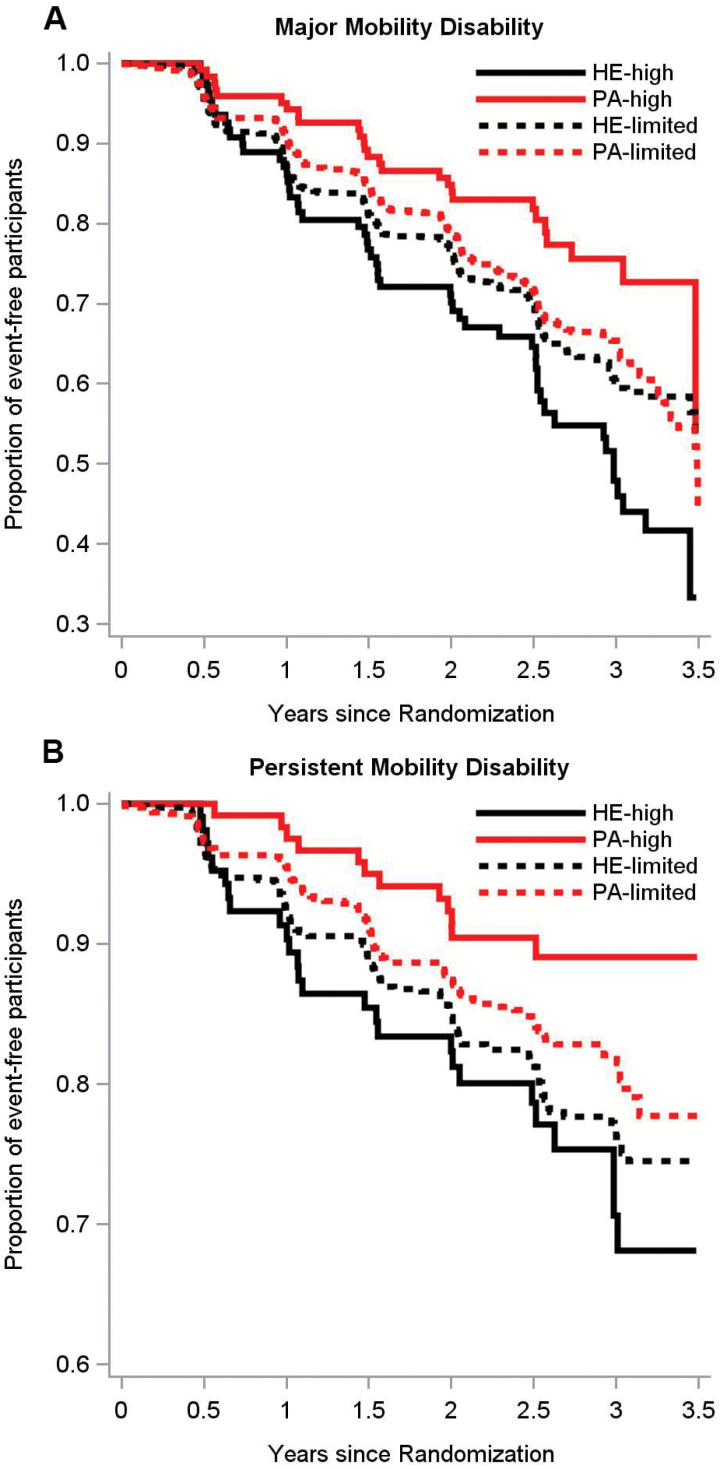

There was a significant intervention by social participation interaction for the dichotomized representation of social participation (p = .003) while the continuous representation exhibited a borderline trend towards significance (p = .054). Figure 1 shows the interaction effect between continuous social participation scores and the interventions on MMD (Figure 1A) and persistent MMD (Figure 1B). There was a stronger intervention effect for higher social participation for both MMD (p = .05) and persistent MMD (p = .16). Overall, 246 participants in the PA group (30.1%) and 290 in the HE group (35.5%) experienced MMD (HR, 0.82 [95% CI, 0.69–0.98]; p = .03), as per previous report (Pahor et al., 2014). Among individuals with high social participation, 27 in the PA group (24.1%) and 52 in the HE group (41.3%) experienced MMD (HR, 0.43 [95% CI, 0.27–0.68]; p < .01). However, individuals with limited social participation showed no benefit with 219 (31.1%) individuals in the PA group and 238 (34.4%) individuals in the HE group experiencing MMD (HR, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.77–1.11]; p = .40). Similar modifying effects of social participation were observed on persistent MMD (interaction effect p = .038, Table 3). These results remained similar after considering education, race, systolic blood pressure, and depression score (Table 3). Sensitivity analyses in Supplementary Table 1 demonstrated that the effect of social participation was seen in two less conservative definitions of high social participation (formal component only and informal component only), as well as a more conservative definition of high social participation. Kaplan–Meier curves show the interaction effect between social participation groups and the interventions on MMD (Figure 2A) and persistent MMD (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Moderating effect of continuously measured social participation on a long-term moderate physical activity intervention to delay the onset of major mobility disability (A) and persistent mobility disability (B). Solid line indicates log-hazard ratio, dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. There was a stronger intervention effect for higher social participation for both major (p = .05) and persistent (p = .16) mobility disability. HE = health education; PA = physical activity.

Figure 2.

Moderating effect of categorically measured social participation on a long-term moderate physical activity intervention to delay the onset of major (A) and persistent (B) mobility disability. There was no effect of baseline social participation on the incidence of major mobility disability (MMD) (p > .40) but there was a significant intervention by social participation interaction (p = .003). Highly social participants randomized to PA had significantly lower incidence of MMD (hazards ratio [HR], 0.43 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.27–0.68]; p < .01) compared with their highly social HE counterparts. Individuals who had limited social participation showed no benefit of the PA intervention (HR, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.77–1.11]; p = .40). There was also a modification of social participation on persistent MMD (p = .038). Individuals with high levels of social participation randomized to PA had significantly lower incidence of persistent MMD compared to those randomized to HE (HR, 0.37 [95% CI, 0.19–0.74]; p < .01). The results of the intervention on individuals with limited social participation showed no effect of PA on persistent MMD compared to those randomized to HE (HR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.62–1.03]; p = .09). HE = health education; PA = physical activity.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that baseline social participation influences the effect of both a structured PA program and, for comparative purposes, a HE program on reducing the incidence of MMD among vulnerable older adults. More specifically, older adults with high levels of social participation have greater mobility benefits from long-term PA compared to HE—a 57% risk reduction compared to 8% for those with limited social participation. The benefit for high social participation was also considerable in comparison to the overall effect of the PA intervention for which there was an 18% risk reduction. This social participation interaction may be influenced by baseline participant characteristics including race, hypertension, and depression. However, the analysis compared effects between randomized intervention arms, not between social participation groups, so therefore baseline characteristics were unlikely to have any meaningful effect on the results. Interestingly, the social participation interaction was not due to differences in adherence to PA as assessed through both objective and subjective measures. This result was surprising considering that social participation is likely driven by intrinsic motivation. In addition, the results of our sensitivity analyses showed that contrasting different cutpoints to capture higher versus lower social participation had only a minimal effect on the association with the results still being significant. Thus, a support system of friends, family, and community might be beneficial to enhancing the effects of PA on mobility outcomes. To our knowledge, this was the first study to examine the influence of social participation on the potential benefit of long-term PA on mobility disability. The results implicate higher levels of social participation as a key component to further the benefit of PA on prevention of mobility disability among older adults.

The measure of social participation used for this study closely mimics previous reports used in several other studies (Donnelly & Hinterlong, 2010; Nilsson et al., 2011; Utz et al., 2002; Zettel-Watson & Britton, 2008). While there is no universal agreement on a definition and thus no normative data for social participation, the categories used in this study were guided by nationally representative samples of older adults’ time use and frequency of leisure activities (Nimrod et al., 2008; Survey Research Institute, Cornell University, 2014; US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014). In our sample, 78% of participants reported visiting with non-cohabitating friends and family at least once per week. By comparison, the prevalence among a sample of 430 adults surveyed over a period of 8 years (initial age, M = 66.2 years) was found to be lower post-retirement, at around 53% (Nimrod et al., 2008). However, comparison to this sample could be argued—when considering the remaining 22% of our sample that reported no weekly visitation, the prevalence among a sample of 189 randomly surveyed older adults (age, M = 72.6, SD = 5.8 years) was a conflicting 6% (Survey Research Institute, Cornell University, 2014). It is worth noting, however, that the former sample may be outdated or biased toward more social individuals, as the surveys were conducted mostly via face-face interview between 1986 and 1994. With the exception of this conflict, our comparisons remain consistent. While our analysis found that 59% of participants attended church and 23% performed volunteer work on a weekly basis, the reported national prevalence for these activities was much lower, at 17% and 19%, respectively (Nimrod et al., 2008). Furthermore, while 27% of our sample reported no social group participation at all, the national prevalence was higher, at 36% (Survey Research Institute, Cornell University, 2014). In brief, our sample appeared to report slightly higher rates of social participation than nationally representative sample populations of older adults, which is likely attributed to the fact that participants in our study were social enough to participate in an intervention versus only complete a survey.

The results of this study contribute to previous knowledge about social participation and onset of disability (Mendes de Leon et al., 2003; Strawbridge, Cohen, Shema, & Kaplan, 1996). Since no previous work has directly examined the combined effects of social participation and PA on disability, our study provides a new understanding for how social participation can contribute to mobility benefits attributed to a PA intervention. Indeed, high levels of social participation are associated with a better mobility response to a structured PA intervention aimed at reducing MMD. With little evidence supporting the role of social participation in the etiological processes of age-related diseases, the effects in the current study are more likely related to the ability to modify the functional consequences of diseases (Mendes de Leon et al., 2003). Perhaps among individuals with high social participation in a structured PA program, their propensity to engage in social situations may translate to a greater proclivity for conversation that naturally focuses on the positive effects of the intervention. As a result, these individuals find their social involvement to be meaningful and procure a heightened sense of purpose and self-efficacy in their functional ability (Mendes de Leon et al., 2003). This theory could also be interpreted as an extension of Festinger’s Social Comparison Theory in which self-enhancement occurs through the positive interpretation of both upward and downward comparison (Festinger, 1954). As such, within the PA intervention, individuals with high social participation may be more prone to social interaction and experience a further benefit from discussing the positive achievements of themselves and those around them. The positive interpretation of this discussion may enhance their sense of control and self-efficacy and enable them to better mitigate age-related changes in physical function (Seeman et al., 1999).

In contrast of high social participation, a growing body of literature suggests that limited social participation (e.g., social isolation) may dull the meaningfulness that older adults hold in their social environments and thus progressively diminish their confidence in remaining functionally independent—a mechanism that has been shown to be critical to functional ability and mobility (Mendes de Leon et al., 2003; Seeman et al., 1999). Furthermore, given the notion that high social participation has a positive effect on an individual’s self-efficacy, the addition of a PA program that also enhances self-efficacy could theoretically combine for added effects on disability outcomes. Unfortunately, since self-efficacy measures were not included in this analysis, these interpretations can only remain speculative.

Our findings showed that while high levels of social participation are associated with an enhanced benefit of PA, they are concurrently associated with a somewhat higher risk of MMD among older adults randomized to HE. We find this result surprising since we expected high levels of social participation to have a beneficial effect on MMD in the HE group but to a lesser degree than the PA group. Perhaps the effect of social participation may be more complex and that the organizational context in which the concept is observed can have both a positive and negative influence on the disability process. When facilitated in the context of PA, it could lead to an enhancement of benefit, while in the context of HE it could serve to reinforce functional decline, possibly through the effect of social comparison and conversation with similar others on self-efficacy (Collins, 1996).

These findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. As this study was a secondary analysis of subgroups, it is by nature not based on a priori randomized comparisons. Another limitation is the consistency of reported social participation behavior was unknown prior to the 4-week recall period used for measurement. Although the social behavior patterns of older adults were previously shown to be relatively constant (Strawbridge et al., 1996), our analysis does not account for this. With no group differences in cognition and with the similarity between self-reported and objective (accelerometer-derived) moderate intensity activity, we do not believe a between groups difference in recall bias existed. Also, since the participant recruitment strategy was vulnerable to self-referral, our sample may not fully represent the entire older adult population. In particular, the recruitment process was dependent on the willingness of older adults to participate in an activity outside their home, which may naturally exclude the most isolated individuals and result in a sample with higher formal social participation levels than the population, which would essentially diminish the effect size. However, it appears this was not the case as our sample actually reported a greater number of individuals with no formal activity compared to a population sample. The amount of center-based face-time individuals experienced may also be an important factor to consider, as the individuals randomized to PA experienced center-based face-time twice weekly throughout the length of the study, while the HE group received center-based face-time once a week for the first 26 weeks and then once or twice a month from there after until the end of the study. It is also worth mentioning that the environment of the PA intervention may have provided an enhanced social component that perhaps could not exist for some individuals when translating the program to those who choose to exercise alone versus in groups. Lastly, our results are limited to a selective population of older adults with low to moderate physical function at risk of experiencing loss of mobility.

The main strength of the present study is the large sample of participants and composite measure of social participation. The LIFE study is the largest and longest duration randomized trial of PA in older adults to date. The objective measurement of MMD used is reliable, validated, and clinically important to the health status of older adults (Newman et al., 2006). Although there is no agreement on the definition and underlying dimensions, the subjective measurement of social participation used is consistent with the context of others in the literature (Shankar, McMunn, & Steptoe, 2010) and an improvement upon definitions used in earlier studies, in that it measures statistically and conceptually unique domains of social engagement and community involvement (Utz et al., 2002). Adherence rates to the PA intervention were similar or higher than those seen in other older adult interventions of shorter duration (Messier et al., 2004).

In conclusion, older adults with high levels of social participation and low to moderate physical function—yet are still able to walk a quarter mile—show an enhanced effect of structured moderate-intensity PA against the onset of MMD compared to similar individuals receiving a HE intervention. Given that there were no differences in the amount of PA between social participation groups, the effect was not likely due to adherence. Rather, the effect may be due to a positive influence in individuals who have a tendency to engage in conversation and contact with others. These findings are important considering that older adults, the fastest growing segment of the population (National Center for Health Statistics, 1998), are at a greater risk of experiencing social isolation which is exacerbated with disability (Levasseur et al., 2010). These findings may imply that encouraging social activities as part and outside of a PA program may incur additional benefit (e.g., exercising in groups, adopting formal and informal social activities, etc.). Future studies should aim at investigating the dual-pronged effect of an intervention designed to increase both PA as well as social participation.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data is available at The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences online.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging Cooperative Agreement (UO1AG22376); a supplement from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (3U01AG022376-05A2S); and sponsored in part by the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. This work was partially supported by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Centers at the University of Florida (1P30AG028740), Wake Forest University (1P30AG21332), Tufts University (1P30AG031679), University of Pittsburgh (P30AG024827), and Yale University (P30AG021342), and the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources Clinical Translational Science Award at Stanford University (UL1RR025744). Tufts University was supported by the Boston Rehabilitation Outcomes Center (1R24HD06568801A1). LIFE investigators were partially supported by the following: Dr. Thomas Gill (Yale University), Academic Leadership Award (K07AG3587) from the National Institute on Aging; and Dr. Roger Fielding (Tufts University), U.S. Department of Agriculture (agreement 58-1950-0-014). Any opinions, findings, conclusion, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Administrative Coordinating Center: University of Florida, Gainesville, FL: Marco Pahor, MD—Principal Investigator of the LIFE Study; Jack M. Guralnik, MD, PhD—Coinvestigator of the LIFE Study (University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD); Christiaan Leeuwenburgh, PhD; Connie Caudle; Lauren Crump, MPH; Latonia Holmes; Jocelyn Lee, PhD; Ching-ju Lu, MPH. Data Management, Analysis, and Quality Control Center: Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, NC: Michael E. Miller, PhD—DMAQC Principal Investigator; Mark A. Espeland, PhD—DMAQC Coinvestigator; Walter T. Ambrosius, PhD; William Applegate, MD; Daniel P. Beavers, PhD, MS; Robert P. Byington, PhD, MPH, FAHA; Delilah Cook, CCRP; Curt D. Furberg, MD, PhD; Lea N. Harvin, BS; Leora Henkin, MPH, Med; John Hepler, MA; Fang-Chi Hsu, PhD; Laura Lovato, MS; Wesley Roberson, BSBA; Julia Rushing, BSPH, MStat; Scott Rushing, BS; Cynthia L. Stowe, MPM; Michael P. Walkup, MS; Don Hire, BS; W. Jack Rejeski, PhD; Jeffrey A. Katula, PhD, MA; Peter H. Brubaker, PhD; Shannon L. Mihalko, PhD; Janine M. Jennings, PhD; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; Evan C. Hadley, MD (National Institute on Aging); Sergei Romashkan, MD, PhD (National Institute on Aging); Kushang V. Patel, PhD (National Institute on Aging); National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD; Denise Bonds, MD, MPH. Field Centers: Northwestern University, Chicago, IL: Mary M. McDermott, MD—Field Center Principal Investigator; Bonnie Spring, PhD—Field Center Coinvestigator; Joshua Hauser, MD—Field Center Coinvestigator; Diana Kerwin, MD—Field Center Coinvestigator; Kathryn Domanchuk, BS; Rex Graff, MS; Alvito Rego, MA. Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA: Timothy S. Church, MD, PhD, MPH—Field Center Principal Investigator; Steven N. Blair, PED (University of South Carolina); Valerie H. Myers, PhD; Ron Monce, PA-C; Nathan E. Britt, NP; Melissa Nauta Harris, BS; Ami Parks McGucken, MPA, BS; Ruben Rodarte, MBA, MS, BS; Heidi K. Millet, MPA, BS; Catrine Tudor-Locke, PhD, FACSM; Ben P. Butitta, BS; Sheletta G. Donatto, MS, RD, LDN, CDE; Shannon H. Cocreham, BS; Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; Abby C. King, PhD—Field Center Principal Investigator; Cynthia M. Castro, PhD; William L. Haskell, PhD; Randall S. Stafford, MD, PhD; Leslie A. Pruitt, PhD; Kathy Berra, MSN, NP-C, FAAN; Veronica Yank, MD; Tufts University, Boston, MA; Roger A. Fielding, PhD—Field Center Principal Investigator; Miriam E. Nelson, PhD—Field Center Coinvestigator; Sara C. Folta, PhD—Field Center Coinvestigator; Edward M. Phillips, MD; Christine K. Liu, MD; Erica C. McDavitt, MS; Kieran F. Reid, PhD, MPH; Won S. Kim, BS; Vince E. Beard, BS; University of Florida, Gainesville, FL; Todd M. Manini, PhD—Field Center Principal Investigator; Marco Pahor, MD—Field Center Coinvestigator; Stephen D. Anton, PhD; Susan Nayfield, MD; Thomas W. Buford, PhD; Michael Marsiske, PhD; Bhanuprasad D. Sandesara, MD; Jeffrey D. Knaggs, BS; Megan S. Lorow, BS; William C. Marena, MT, CCRC; Irina Korytov, MD; Holly L. Morris, MSN, RN, CCRC (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL); Margo Fitch, PT (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL); Floris F. Singletary, MS, CCC-SLP (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL); Jackie Causer, BSH, RN (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL); Katie A. Radcliff, MA (Brooks Rehabilitation Clinical Research Center, Jacksonville, FL); University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; Anne B. Newman, MD, MPH—Field Center Principal Investigator; Stephanie A. Studenski, MD, MPH—Field Center Coinvestigator; Bret H. Goodpaster, PhD; Nancy W. Glynn, PhD; Oscar Lopez, MD; Neelesh K. Nadkarni, MD, PhD; Kathy Williams, RN, BSEd, MHSA; Mark A. Newman, PhD; George Grove, MS; Janet T. Bonk, MPH, RN; Jennifer Rush, MPH; Piera Kost, BA (deceased); Diane G. Ives, MPH; Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, NC; Stephen B. Kritchevsky, PhD—Field Center Principal Investigator; Anthony P. Marsh, PhD—Field Center Coinvestigator; Tina E. Brinkley, PhD; Jamehl S. Demons, MD; Kaycee M. Sink, MD, MAS; Kimberly Kennedy, BA, CCRC; Rachel Shertzer-Skinner, MA, CCRC; Abbie Wrights, MS; Rose Fries, RN, CCRC; Deborah Barr, MA, RHEd, CHES; Yale University, New Haven, CT; Thomas M. Gill, MD—Field Center Principal Investigator; Robert S. Axtell, PhD, FACSM—Field Center Coinvestigator (Southern Connecticut State University, Exercise Science Department); Susan S. Kashaf, MD, MPH (VA Connecticut Healthcare System); Nathalie de Rekeneire, MD, MS; Joanne M. McGloin, MDiv, MS, MBA; Karen C. Wu, RN; Denise M. Shepard, RN, MBA; Barbara Fennelly, MA, RN; Lynne P. Iannone, MS, CCRP; Raeleen Mautner, PhD; Theresa Sweeney Barnett, MS, APRN; Sean N. Halpin, MA; Matthew J. Brennan, MA; Julie A. Bugaj, MS; Maria A. Zenoni, MS; Bridget M. Mignosa, AS. Cognition Coordinating Center: Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, NC; Jeff Williamson, MD, MHS—Center Principal Investigator; Kaycee M Sink, MD, MAS—Center Coinvestigator; Hugh C. Hendrie, MB, ChB, DSc (Indiana University); Stephen R. Rapp, PhD; Joe Verghese, MB, BS (Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University); Nancy Woolard; Mark Espeland, PhD; Janine Jennings, PhD. Electrocardiogram Reading Center: University of Florida, Gainesville, FL; Carl J. Pepine MD, MACC; Mario Ariet, PhD; Eileen Handberg, PhD, ARNP; Daniel Deluca, BS; James Hill, MD, MS, FACC; Anita Szady, MD. Spirometry Reading Center: Yale University, New Haven, CT; Geoffrey L. Chupp, MD; Gail M. Flynn, RCP, CRFT; Thomas M. Gill, MD; John L. Hankinson, PhD (Hankinson Consulting, Inc.); Carlos A. Vaz Fragoso, MD. Cost Effectiveness Analysis Center: Erik J. Groessl, PhD (University of California, San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System); Robert M. Kaplan, PhD (Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health).

Contributor Information

LIFE Study Investigators:

Marco Pahor, Jack M Guralnik, Christiaan Leeuwenburgh, Connie Caudle, Lauren Crump, Latonia Holmes, Jocelyn Lee, Ching-ju Lu, Winston Salem, Michael E Miller, Mark A Espeland, Walter T Ambrosius, William Applegate, Daniel P Beavers, Robert P Byington, Delilah Cook, Curt D Furberg, Lea N Harvin, Leora Henkin, John Hepler, Fang-Chi Hsu, Laura Lovato, Wesley Roberson, Julia Rushing, Scott Rushing, Cynthia L Stowe, Michael P Walkup, Don Hire, W Jack Rejeski, Jeffrey A Katula, Peter H Brubaker, Shannon L Mihalko, Janine M Jennings, Evan C Hadley, Sergei Romashkan, Kushang V Patel, Denise Bonds, Mary M McDermott, Joshua Hauser, Diana Kerwin, Kathryn Domanchuk, Rex Graff, Alvito Rego, Timothy S Church, Steven N Blair, Valerie H Myers, Ron Monce, Nathan E Britt, Melissa Nauta Harris, Ami Parks McGucken, Ruben Rodarte, Heidi K Millet, Catrine Tudor-Locke, Ben P Butitta, Sheletta G Donatto, Shannon H Cocreham, Abby C King, Cynthia M Castro, William L Haskell, Randall S Stafford, Leslie A Pruitt, Kathy Berra, Veronica Yank, Roger A Fielding, Miriam E Nelson, Sara C Folta, Edward M Phillips, Christine K Liu, Erica C McDavitt, Kieran F Reid, Won S Kim, Vince E Beard, Todd M Manini, Marco Pahor, Stephen D Anton, Thomas W Buford, Michael Marsiske, Bhanuprasad D Sandesara, Jeffrey D Knaggs, Megan S Lorow, William C Marena, Irina Korytov, Holly L Morris, Margo Fitch, Floris F Singletary, Jackie Causer, Katie A Radcliff, Anne B Newman, Stephanie A Studenski, Bret H Goodpaster, Nancy W Glynn, Oscar Lopez, Neelesh K Nadkarni, Kathy Williams, Mark A Newman, George Grove, Janet T Bonk, Jennifer Rush, Piera Kost, Diane G Ives, Stephen B Kritchevsky, Anthony P Marsh, Tina E Brinkley, Jamehl S Demons, Kaycee M Sink, Kimberly Kennedy, Rachel Shertzer-Skinner, Abbie Wrights, Rose Fries, Deborah Barr, Thomas M Gill, Robert S Axtell, Susan S Kashaf, Nathalie de Rekeneire, Joanne M McGloin, Karen C Wu, Denise M Shepard, Barbara Fennelly, Lynne P Iannone, Raeleen Mautner, Theresa Sweeney Barnett, Sean N Halpin, Matthew J Brennan, Julie A Bugaj, Maria A Zenoni, Bridget M Mignosa, Jeff Williamson, Kaycee M Sink, Hugh C Hendrie, Stephen R Rapp, Joe Verghese, Nancy Woolard, Mark Espeland, Janine Jennings, Carl J Pepine, Mario Ariet, Eileen Handberg, Daniel Deluca, James Hill, Anita Szady, Geoffrey L Chupp, Gail M Flynn, Thomas M Gill, John L Hankinson, Carlos A Vaz Fragoso, Erik J Groessl, and Robert M Kaplan

References

- Avlund K. Lund R. Holstein B. E., & Due P (2004). Social relations as determinant of onset of disability in aging. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 38, 85–99. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2003.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton D. E. Tarasuk V. Katz J. N. Wright J. G., & Bombardier C (2001). “Are you better?” A qualitative study of the meaning of recovery. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 45, 270–279. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200106)45:3<270::AID-ART260> 3.0.CO;2-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg G. (1988). Perceived exertion and pain scales. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Brawley L. Rejeski W. J. Gaukstern J. E., & Ambrosius W. T (2012). Social cognitive changes following weight loss and physical activity interventions in obese, older adults in poor cardiovascular health. Annals of Behavorial Medicine, 44, 353–64. doi:10.1007/s12160-012-9390-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke S. M. Carron A. V. Eys M. A. Ntoumanis N., & Estabrooks P. A (2006). Group versus individual approach? A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity. Sport and Exercise Psychology Review, 2, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. L. (1996). For better or worse: The impact of upward social comparison on self-evaluations. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 51–69. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.51 [Google Scholar]

- de Vries N. M., van Ravensberg C. D., Hobbelen J. S., Olde Rikkert M. G., Staal J. B., Nijhuis-van der Sanden M. W. (2012). Effects of physical exercise therapy on mobility, physical functioning, physical activity and quality of life in community-dwelling older adults with impaired mobility, physical disability and/or multi-morbidity: A meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 11, 136–149. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly E. A., Hinterlong J. E. (2010). Changes in social participation and volunteer activity among recently widowed older adults. The Gerontologist, 50, 158–169. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140. doi:10.1177/001872675400700202 [Google Scholar]

- Gow A. J., Corley J., Starr J. M., Deary I. J. (2013). Which social network or support factors are associated with cognitive abilities in old age?Gerontology, 59, 454–463. doi:10.1159/000351265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik J. M. (1995). Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med, 332, 556–561. doi:10.1056/NEJM199503023320902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horhota M. Stroup H., & Price A (2013). Are intergenerational exercise classes threatening or motivating for older adults? A pilot study. Journal of Athletic Medicine, 1, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kampfe C. M. (2015). Counseling older people: Opportunities and challenges. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. doi:10.1002/9781119222767 [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan G. A., Lazarus N. B., Cohen R. D., Leu D. J. (1991). Psychosocial factors in the natural history of physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 7, 12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I., & Berkman L. F (2001). Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health, 78, 458–467. doi:10.1093/jurban/78.3.458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Subramanian S. V., Gortmaker S. L., Kawachi I. (2006). US state- and county-level social capital in relation to obesity and physical inactivity: A multilevel, multivariable analysis. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 63, 1045–1059. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur M., Richard L., Gauvin L., Raymond E. (2010). Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: Proposed taxonomy of social activities. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 71, 2141–2149. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthew C. E. (2005). Calibration of accelerometer output for adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 37, S512–S522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley E. Lox C., & Duncan T. E (1993). Long-term maintenance of exercise, self-efficacy, and physiological change in older adults. Journal of Gerontology, 48, 218–224. doi:10.1093/geronj/48.4.P218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley E., Morris K. S., Doerksen S. E., Motl R. W., Liang H., White S. M.,…, Rosengren K. (2007). Effects of change in physical activity on physical function limitations in older women: Mediating roles of physical function performance and self-efficacy. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55, 1967–1973. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01469.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes de Leon C. F. Glass T. A., & Berkman L. F (2003). Social engagement and disability in a community population of older adults: The New Haven EPESE. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157, 633–642. doi:10.1093/aje/kwg028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier S. P., Loeser R. F., Miller G. D., Morgan T. M., Rejeski W. J., Sevick M. A.,…, Williamson J. D. (2004). Exercise and dietary weight loss in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: The Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 50, 1501–1510. doi:10.1002/art.20256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen S. P., McAuley E., Satariano W. A., Kealey M., Prohaska T. R. (2012). Physical activity and functional limitations in older adults: The influence of self-efficacy and functional performance. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 354–361. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbs036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (1998). Vital statistics of the United States, 1994; Preprint of Vol. II, Mortality, Part A, Sec 6, Life Tables. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Newman A. B., Simonsick E. M., Naydeck B. L., Boudreau R. M., Kritchevsky S. B., Nevitt M. C.,…, Harris T. B. (2006). Association of long-distance corridor walk performance with mortality, cardiovascular disease, mobility limitation, and disability. JAMA, 295, 2018–2026. doi:10.1001/jama.295.17.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson C. J., Avlund K., Lund R. (2011). Onset of mobility limitations in old age: The combined effect of socioeconomic position and social relations. Age and Ageing, 40, 607–614. doi:10.1093/ageing/afr073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimrod G. Janke M. C., & Kleibe D. A (2008). Retirement, activity, and subjective well-being in Israel and the Unites States. World Leisure Journal, 50, 18–32. doi:10.1080/04419057.2008.9674524 [Google Scholar]

- Pahor M., Guralnik J. M., Ambrosius W. T., Blair S., Bonds D. E., Church T. S., Williamson J. D. (2014). Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: The LIFE study randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 311, 2387–2396. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.5616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rejeski W. Brawley L. Ambrosius W. Brubaker P. Focht B. Foy C., & Fox L (2003). Older adults with chronic disease: Benefits of group-mediated counseling in the promotion of physically active lifestyles. Health Psychol, 22, 414–423. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T. E. Unger J. B. McAvay G., & Mendes de Leon C. F (1999). Self-efficacy beliefs and perceived declines in functional ability: MacArthur studies of successful aging. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 4, 214–222. doi:10.1093/geronb/54B.4.P214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A., McMunn A., Steptoe A. (2010). Health-related behaviors in older adults relationships with socioeconomic status. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38, 39–46. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen L. V. Axelsen U., & Avlund K (2002). Social participation and functional ability from age 75 to age 80. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 9, 71–78. doi:10.1080/110381202320000052 [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A. L. Verboncoeur C. J. McLellan B. Y. Gillis D. E. Rush S. Mills K. M.,...Bortz W. M. 2nd(2001). Physical activity outcomes of CHAMPS II: a physical activity promotion program for older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56, M465-M470. doi:10.1093/gerona/56.8.M465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge W. J. Cohen R. D. Shema S. J., & Kaplan G. A (1996). Successful aging: Predictors and associated activities. American Journal of Epidemiology, 144, 135–141. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Survey Research Institute, Cornell University (2014). Cornell National Social Survey (CNSS), 2013. CISER version 1. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Institute for Social and Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. E., Lobel M. (1989). Social comparison activity under threat: Downward evaluation and upward contacts. Psychological Review, 96, 569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2014). American Time Use Survey - 2014 Results Retrieved January 20, 2016, from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/atus.t11.htm

- Utz R. L. Carr D. Nesse R., & Wortman C. B (2002). The effect of widowhood on older adults’ social participation: An evaluation of activity, disengagement, and continuity theories. Gerontologist, 42, 522–533. doi:10.1093/geront/42.4.522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zettel-Watson L., Britton M. (2008). The impact of obesity on the social participation of older adults. The Journal of General Psychology, 135, 409–423. doi:10.3200/GENP.135.4.409-424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.