Abstract

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has been used extensively to investigate white matter (WM) microstructural changes during healthy adult aging. However, WM fibres are known to shrink throughout the lifespan, leading to larger interstitial spaces with age. This could allow more extracellular free water molecules to bias DTI metrics, which are relied upon to provide WM microstructural information. Using a cohort of 212 participants, we demonstrate that WM microstructural changes in aging are potentially less pronounced than previously reported once the free water compartment is eliminated. After free water elimination, DTI parameters show age-related differences that match histological evidence of myelin degradation and debris accumulation. The fraction of free water is further shown to associate better with age than any of the conventional DTI parameters. Our findings suggest that DTI analyses involving free water are likely to yield novel insight from retrospective re-analysis of data and to answer new questions in ongoing DTI studies of brain aging.

Keywords: magnetic resonance imaging, diffusion tensor imaging, healthy adult aging, white matter, free water

It has long been known that white matter (WM) tissue degenerates throughout the brain during healthy adult aging (Meier-Ruge et al., 1992). In particular, age-associated decline in WM volume appears more prominent than similar declines in grey matter volume (Piguet et al., 2009). Primary degeneration of the WM with advancing age occurs through loss of axonal fibres (Marner et al., 2003) following deformation and degradation of the myelin sheath (Peters, 2002; Tang et al., 1997). Secondary Wallerian degeneration may occur as a result of distal neuronal injury, marked by glial cell infiltration in degenerating axons (Rotshenker, 2011). In general, degeneration has been shown to result from the cell’s inability to endure debris accumulation (Neumann et al., 2009) due to impairment of paravascular clearance (Kress et al., 2014). A wide variety of debris have been found to accumulate in the aging brain such as amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles and Lewy bodies (Davis et al., 1999; Elobeid et al., 2016; Knopman et al., 2003). Fragments of degraded myelin have also been found to accumulate in microglial lysosomes, further burdening clearance function (Safaiyan et al., 2016).

Much of what is known about the in-vivo aging human white matter microstructure has been learned through diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging (DTI) (Cox et al., 2016; Lebel et al., 2012; Madden et al., 2012; Sullivan and Pfefferbaum, 2006). DTI models the microscopic diffusion of water molecules, and the majority of DTI aging studies have revealed a decrease in fractional anisotropy (FA) of diffusion and an increase in mean diffusivity (MD) with advancing age. MD can further be broken down into radial (RD) and axial (AD) diffusivity, of which RD has been consistently found to increase with age, thought to reflect decreased myelin integrity with age (Madden et al., 2012). On the other hand, relationships between AD and age have been less consistent. Increased AD with age likely reflects increased extracellular water or total axonal loss, while decreases in AD with age suggest accumulation of debris or metabolic damage with age (Madden et al., 2012). Furthermore, these age-related differences have a well-documented spatial distribution. Associations with age are more pronounced in later-myelinating regions, particularly anterior regions, than earlier-myelinating regions. This concept is known as the “anterior-posterior gradient of aging” (Bennett et al., 2010; Head et al., 2004; Pfefferbaum et al., 2005; Yoon et al., 2008). Additionally, age-related differences have been shown to be stronger in thalamic radiations and association fibres and weaker in projection fibres (Cox et al., 2016). In particular, projection fibres of the corticospinal tract have been found to remain relatively compact with age while nearby fibres degenerate (Jang and Seo, 2015).

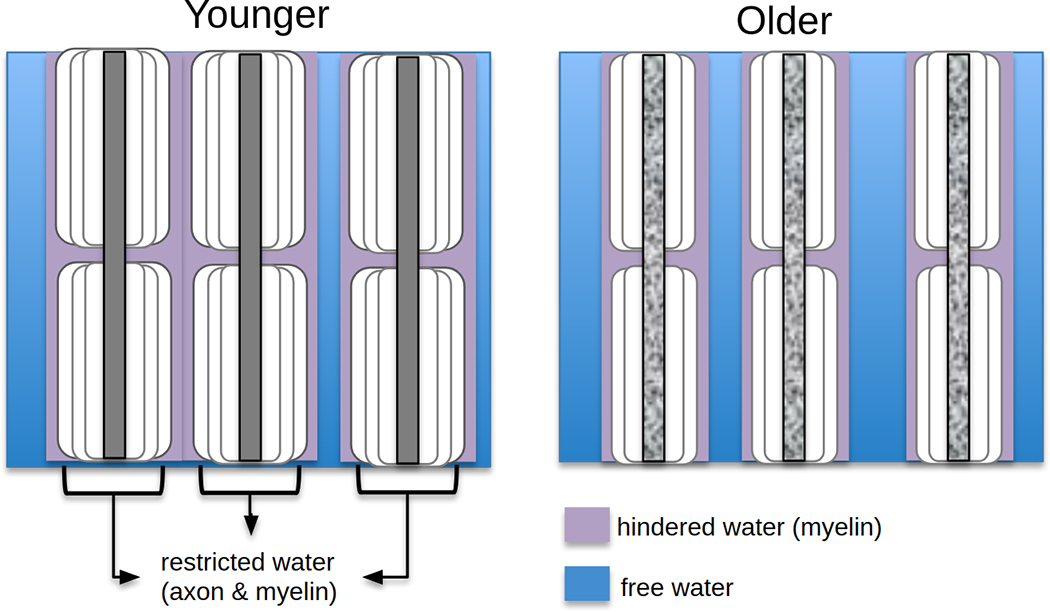

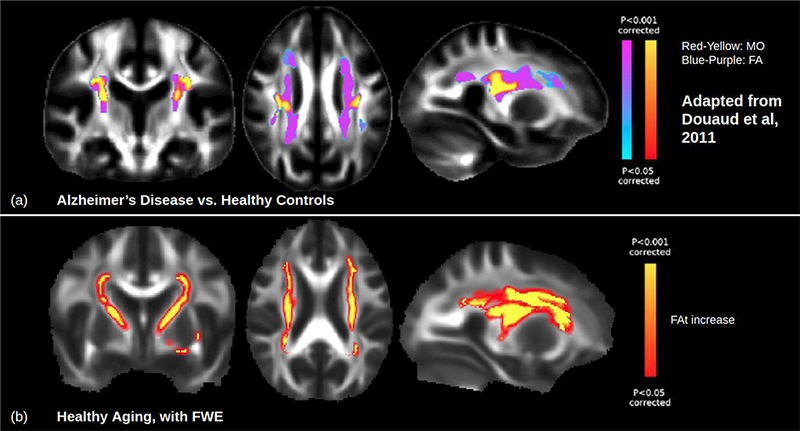

Despite the abundant literature, the mechanisms behind age-related differences in DTI parameters are not yet clear, as DTI metrics do not necessarily reflect WM microstructure alone (Winston, 2012). A main caveat of most DTI-age analyses is that age-related WM degeneration can lead to enlarged interstitial spaces (Meier-Ruge et al., 1992) and hence increased partial-voluming effects between WM fibres and extracellular water (Fig. 1). While much of the interstitial diffusion is expected to be hindered in the healthy brain, age-related tissue shrinkage may allow more interstitial water to diffuse in large enough spaces where the molecules are effectively free (effectively unhindered) within the chosen diffusion time. Such limitations obscure our ability to observe true microstructural effects. Further complicating the interpretations of age-related differences is the insufficiency of DTI to distinguish crossing fibres within a voxel (Basser et al., 2000). For example, an increase in FA is often found in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease relative to healthy controls in the corona radiata and internal capsule, and has been suggested to reflect selective degeneration of non-principal fibres crossing the corticospinal tract (Doan et al., 2017; Douaud et al., 2011; Mito et al., 2018; Teipel et al., 2014). This FA increase is typically not observed in healthy aging, although it was recently seen in a cross-sectional study of 5,000 UK Biobank participants (Miller et al., 2016) and a longitudinal study involving >500 participants (de Groot et al., 2016). Thus far, such findings have not been reported by smaller-scale cross-sectional DTI studies of aging as the effect may be obscured by inter-subject variability.

Fig. 1. Schematic of white matter degeneration.

White matter degeneration leads to increased interstitial space at older ages. Intracellular water diffusion is restricted, while nearby extracellular water is hindered by myelin layers and other tissue components (purple). In the deep interstitial spaces, water is far enough from boundaries such that it can diffuse freely within a short diffusion time (blue).

Free water and crossing fibre effects can potentially be better accounted for with multi-shell acquisitions (using more than one non-zero b-value) for diffusion models that are more tissue-specific than DTI, such as Neurite Orientation Dispersion and Density Imaging (NODDI) (Zhang et al., 2012). The NODDI model includes a separated isotropic diffusion compartment (isoVF) representing extracellular free water, and NODDI has been used to show a positive association of isoVF and age in the deep white matter (Billiet et al., 2015; Cox et al., 2016). However, NODDI cannot measure age-related differences in restricted or hindered diffusivities, and the model relies on several assumptions that have been disputed (Lampinen et al., 2017). Furthermore, multi-shell acquisitions are often not feasible for large-scale studies or available in legacy data.

Efforts to account for free water in single-shell DTI have been on the rise in recent years. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery has been used to suppress cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in WM DTI (Papadakis et al., 2002) but the efficacy has been limited due to a reduced signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and longer scan times. Moreover, interstitial water remains unaccounted for. Regression of WM volume (Bendlin et al., 2010) was also met with limited success, as the relationship between brain volume and free water is highly nonlinear (Metzler-Baddeley et al., 2012). Free water elimination (FWE) has subsequently been proposed to explicitly model a free water compartment in addition to a tissue compartment (Pasternak et al., 2009; Pierpaoli and Jones, 2004). Free water fraction is parametrized in each voxel through the parameter f, ranging between 0 and 1. The FWE technique finds high f values in the CSF within the ventricles and around the brain parenchyma, but also finds a non-zero f throughout the brain (Pasternak et al., 2009), likely reflective of large interstitial spaces. Free water maps therefore seem promising for mapping degenerated spaces. FWE-DTI metrics have demonstrated significantly higher test-retest reliability than conventional DTI parameters (Albi et al., 2017), and have already provided insight on microstructural brain changes in conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (Maier-Hein et al., 2015), depression (Bergamino et al., 2016), schizophrenia (Mandl et al., 2015), Parkinson’s disease (Ofori et al., 2015), Huntington’s disease (Steventon et al., 2016), and bipolar disorder (Tuozzo et al., 2017). Importantly, FWE-DTI does not require custom data acquisitions and can be applied post-acquisition to any DTI sequence. This is an invaluable advantage that allows us to harness the power of the existing and ongoing large-scale DTI studies.

In this study, we apply FWE-DTI in a cohort of 212 healthy adults to examine the effect of healthy aging on WM microstructure. We assess the extent of new information provided by the use of FWE compared to conventional DTI analyses, in the context of both WM atrophy and known crossing fibres. Furthermore, we establish the free water fraction, f, as a more robust indicator of age-related WM changes than conventional or free-water corrected DTI parameters.

Methods

Participants and Study Design

Cognitively healthy middle-aged and older adults were recruited through the Massachusetts General Hospital, the local community, and local senior centers. Participants were excluded if they had major neurologic or psychiatric illnesses, history of stroke, significant head trauma, brain surgery or substance abuse, unstable medical illness, cancer within the nervous system or contraindication for MRI scan. Participants with controlled hypertension, dyslipidemia, or type 2 diabetes were not excluded. The resulting cohort consisted of 212 participants (82 males, 130 females) aged 39.1 to 91.7 years (62.0 + 11.2) that were physically healthy, cognitively intact, and literate with at least a high school education. Information on the participants is provided in Table 1. A subset of this cohort has previously been reported on (Chen et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics.

| Participant Demographics (N=212) | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62.0 + 11.2; range 39.1 to 91.7 |

| MMSE score* | 28.8 + 1.30; range 24 to 30 |

| Sex | 82 male; 130 female |

Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores not available for 3 participants.

The study was approved (#2008P001486/MGH) by the Partners Healthcare Internal Review Board and followed the Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, generally known as the Belmont Report. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in this research.

MRI Acquisition

All participants were imaged on a 3T Siemens Magnetom Trio system with a 12-channel head coil. Diffusion MRI (dMRI) was obtained using single-shot echo planar imaging with a twice-refocused spin-echo sequence: 60 directions with b=700mm2/s following 10 b=0 volumes, echo time (TE) = 83 ms, repetition time (TR) = 7.98s, field-of-view (FOV) = 25.6 cm, 2mm3 resolution, 64 slices.

Pre-Processing

All dMRI data sets were corrected for motion and eddy currents using eddy_correct (Jenkinson et al., 2002) in FSL (Smith et al., 2004) and masked using FSL’s Brain Extraction Toolbox (bet) (Smith, 2002). FWE was performed (Pasternak et al., 2009) by fitting the signal S:

| (1) |

where S0 is signal from the non diffusion weighted (b=0) volumes, f is the fraction of the signal attributed to free water, b is the diffusion weighting (a.k.a b-value), q is the normalized diffusion gradient direction, Dtiss is the diffusion tensor modeling the tissue compartment and dfw =3×10−3 mm2/s is the diffusion coefficient of free water. The free parameters are Dtiss and f. Eigen decomposition of Dtiss resulted in DTI parameters specifically for the tissue compartment (indicated by a ‘t’ suffix, i.e., MDt, RDt, ADt, FAt), and the fraction of free water f per voxel provided a free water map. Diffusion tensors were parameterized with Euclidean coordinates based on results of (Pasternak et al., 2010) and underwent Laplace-Beltrami regularization to stabilize the fit (Pasternak et al., 2009). Conventional, non-FWE DTI was also performed by fitting the single-tensor model via in-house MATLAB code (Mathworks, USA).

Statistical Analysis

To examine the spatial distribution of age-related differences, voxelwise statistical analysis was conducted in the white matter by extracting a WM skeleton using FSL’s Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (TBSS) (Smith et al., 2006). A relationship of DTI parameters with age was defined by p<0.05 with correction for multiple comparisons (cluster-wise controlling family-wise error rate with 500 permutations) and controlling for gender as per FSL’s Threshold-Free Cluster Enhancement (TFCE).

FreeSurfer (Fischl, 2012) was used to calculate cerebral WM volume for each subject. Effect size of DTI parameters was also calculated via FreeSurfer using a general linear model. Regions of interest were assessed using an MNI White Matter Atlas (John Hopkins University). To aid with interpreting results, FSL’s bedpostx tool (Jbabdi et al., 2010) was used to compute the estimated proportion of primary (mean_f1 samples) and secondary (mean_f2samples) fibre orientations within each voxel. These two parameters underwent the same statistical analysis versus age as above.

Unless stated otherwise, images are displayed in RAS (neurological) orientation (i.e., the left of an axial image is in the left hemisphere of the brain).

Results

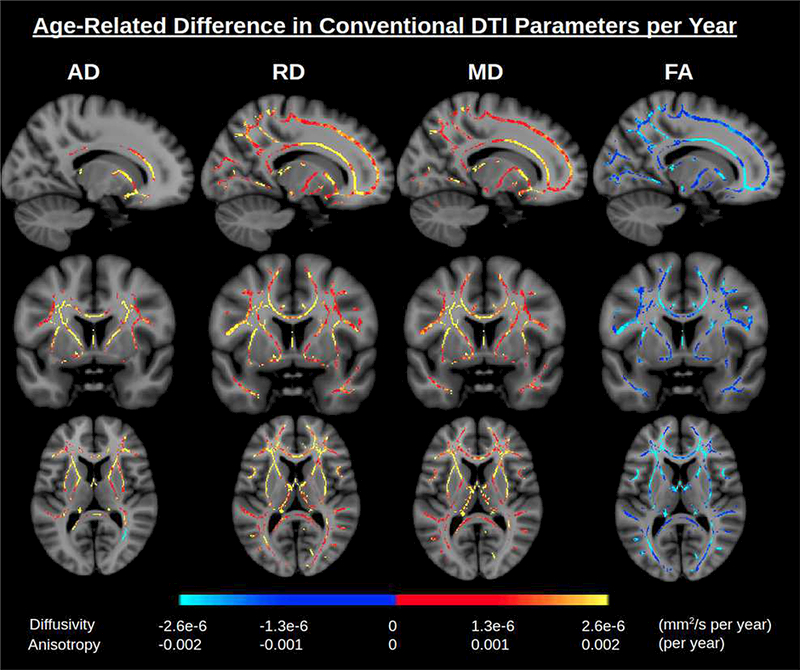

Tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) of conventionally modeled DTI parameters in the 212-participant cohort shows widespread positive associations of MD and RD with age as well as negative associations of FA with age throughout the WM. These associations with age are more profound in anterior than posterior regions (Fig. 2). Correlations of age and AD are less consistent. AD has positive associations with age throughout the medial WM, including the corpus callosum, corona radiata, external and internal capsule. Most lateral WM shows no association between AD and age, excepting negative associations in select inferiofrontal regions of the left hemisphere, including the forceps minor, and in posterior portions of the right hemisphere.

Fig. 2. Age-related differences in conventional DTI parameters.

Significant associations of DTI parameters with age are displayed based on a linear model (conventional DTI, without FWE). Color scales display effect size (change per year). A general trend is an increase in diffusivity parameters with age and a decrease in anisotropy with age. An anterior-posterior gradient is apparent. Abbreviations: DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; FWE, free water elimination.

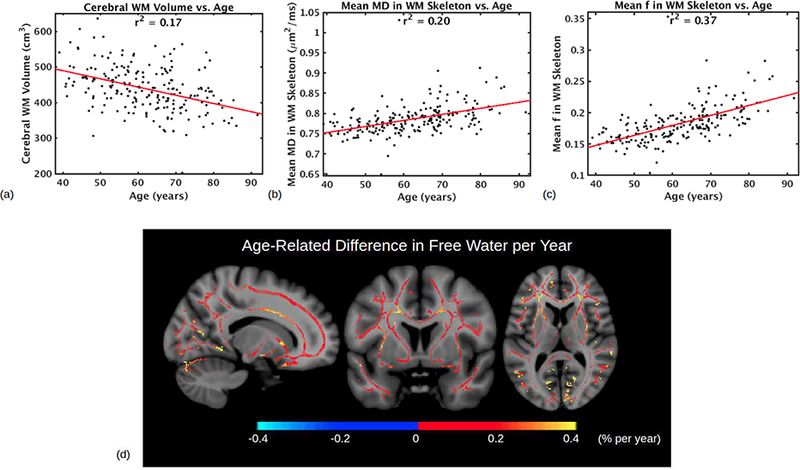

Like MD, free water fraction has a positive association with age as WM volume has a negative association. The relationship between free water, WM volume and age is detailed in Supplementary Appendix A. The WM skeleton-average free water fraction f displays a stronger correlation with age (r=0.61) than WM volume (r=−0.41) and MD (r = 0.45) (Fig. 3a-c). Moreover, the increases in f with age also follow an anterior-to-posterior gradient. For instance, in the corpus callosum, free water occupies an additional 0.26% per year in the genu (r=0.53), in contrast to 0.17% per year in the body (r=0.44) and 0.10% per year in the splenium (r=0.24) (Supplementary Fig. S1). The f-maps illustrate increasing free water with age throughout the white matter, particularly in anterior regions (Fig. 3d). Free water is seen to occupy an additional 0.2% of most WM voxels each year, an additional 10% (ranging from 14% to 24%) across the age span used in this study (age 40–90, Fig. 3c). Throughout the WM, the p-values for age-related differences in f are lower than for age-related differences in conventional DTI parameters, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Fig. 3. Free water as a robust marker of aging.

(a)-(c) compares different plots which aim to summarize WM degeneration with age. (a) Cerebral WM volume (cm3) vs. age, as calculated by FreeSurfer during cortical reconstruction. r = −0.4097, moderate correlation. (b) WM skeleton average of mean diffusion (MD, mm2/s) vs. age, as calculated from conventional DTI without FWE. r = 0.4503, moderate correlation. (c) WM skeleton average free water fraction f vs. age. r = 0.6052, strong correlation. (d) Significant positive association of free water fraction f with age in WM voxels. Color scale denotes the age-related difference in intravoxel free water percentage per year. The increase is more apparent in anterior regions than posterior regions. Abbreviations: DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; FWE, free water elimination; MD, mean diffusivity; WM, white matter.

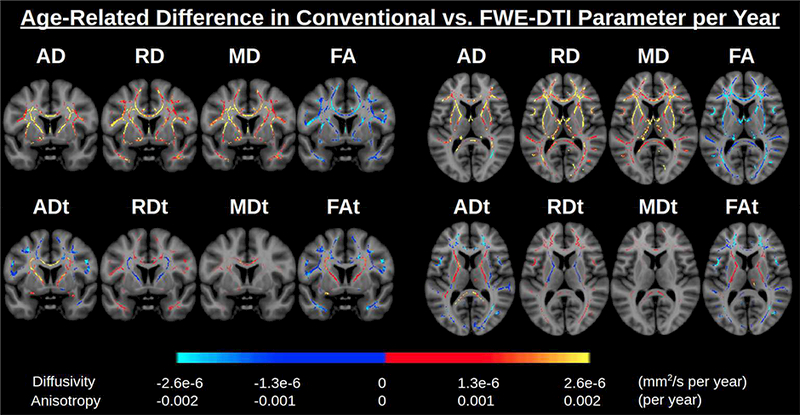

Regions showing positive associations of f with age largely overlap with those showing positive associations of diffusivity with age in the conventional DTI measures. After FWE, the age-related differences are much diminished in all DTI parameters, with opposite trends now emerging (Fig. 4). FWE-DTI parameters are given a “t” suffix (for “tissue”). Notably, in lateral WM areas (ie, lateral to the superior corona radiata and internal capsule), we observe positive associations of RDt and negative associations of ADt with age, along with negative associations of FAt with age and negligible age-related differences in MDt in these regions. These trends mostly follow an anterior-posterior gradient. The corresponding p-value maps are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. In WM regions thought to remain relatively spared by aging, such as the medial corpus callosum (Chen et al., 2013), splenium of corpus callosum (Madden et al., 2012) and inferior corticospinal tract (Jang and Seo, 2015), we now observe positive associations of ADt with age, contrary to the overarching trend of decreased ADt with age. Average age-associations in the WM skeleton are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 4. The effect of free water elimination (FWE) on DTI parameters.

Color scales display the age-related difference in DTI parameter per year (only significant effects at p<0.05 are shown). Conventional DTI shows a large increase in diffusivity parameters per year. After FWE, these effect sizes are diminished. Conventional DTI also shows a large decrease in FA per year, much of which remains after FWE, likely reflecting decreased microstructural myelin integrity. Other areas, such as the superior corona radiata and the internal capsule, display increased FAt with age, accompanied by increased ADt with age and decreased RDt with age. These age-related differences can only be seen after FWE. Abbreviations: DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; FA, fractional anisotropy; FWE, free water elimination.

Table 2. Correlation coefficients (r) of DTI parameters vs. age, averaged over WM skeleton.

The parameter with the greatest correlation with age, f, is shown in bold. All correlations significant at p<0.05 except for MDt. Key: AD, axial diffusivity; DTI, Diffusion tensor imaging; FA, fractional anisotropy; MD, mean diffusivity; RD, radial diffusivity; WM, white matter.

| Parameter | Correlation (r) with age |

|---|---|

| AD | 0.2595 |

| RD | 0.4972 |

| MD | 0.4503 |

| FA | –0.5071 |

| f | 0.6052 |

| ADt | –0.2016 |

| RDt | 0.1721 |

| MDt | 0.0248 |

| FAt | –0.2510 |

Lastly, in the superior corona radiata and internal capsule, we observe positive associations of ADt and negative associations of RDt with age (Fig. 4), with a corresponding positive association of FAt, contrasting the known prevalence of FA decrease with age. In these exact regions, bedpostx tractography, which resolves crossing fibres, suggests that the primary fibre tract proportion is uncorrelated with age, whereas the proportion of secondary fibre tracts has a negative association with age (see Fig. 6). Tissue mode of anisotropy (MOt), which measures the linearity of diffusion (Ennis and Kindlmann, 2006), also has a positive association with age in these regions.

Discussion

In this work, we found a positive association of free water with age throughout the white matter, likely reflective of enlarged interstitial spaces at older ages. This free water fraction is strongly correlated with age, and its elimination is shown to substantially alter age-related differences in DTI parameters.

In our results based on conventional DTI, diffusivity (AD, RD, MD) is generally seen to increase or display no association with age. These trends, as shown in Fig. 2, support the anterior-posterior gradient of aging (Bennett et al., 2010; Head et al., 2004; Pfefferbaum et al., 2005; Yoon et al., 2008) and the “last-in-first-out” theory (Davis et al., 2009) in which WM regions that are myelinated at later stages, generally anterior regions, are the earliest to undergo degeneration and hence WM fibre shrinkage.

However, with FWE, more negative associations of ADt with age are revealed, which, in conjunction with positive associations of RDt with age in the same regions, strongly suggest age-related axonal damage, culminating in an accumulation of cellular debris and metabolic damage (Wyss-Coray, 2016) and a decline in myelin-sheath integrity with age (Peters, 2002). These post- FWE trends thus correspond well to the histological evidence of aging WM microstructure (Marner et al., 2003; Meier-Ruge et al., 1992; Piguet et al., 2009; Tang et al., 1997), and these trends cannot be fully observed without accounting for free water.

Notably, we found an age-associated increase in post-FWE FA (FAt) in the superior corona radiata and internal capsule, accompanied by an ADt increase and RDt decrease. While a higher FAt in older adults may seem counterintuitive, it is precisely what is reported among Alzheimer’s subjects (Doan et al., 2017; Douaud et al., 2011; Mito et al., 2018; Teipel et al., 2014). It is conceivable that as these latter are patients, the FA increase is found even without applying FWE, and interpreted as being due to selective degeneration of non-dominant fibre tracts at fibre crossings (Fig. 5a). In the present study, we found that a similarly-located, albeit more subtle FA increase takes place in healthy aging (Fig. 5b). The only other reports of this increased FA in normal aging come from a large-scale study of 5,000 UK Biobank participants (Miller et al., 2016) and a large-scale longitudinal study (N = 501) (de Groot et al., 2016). The fact that this has not been reported in smaller-scale cross-sectional studies of healthy aging suggests that the effect may usually be masked by inter-subject variability associated with interstitial free water, and that FWE is necessary for elevating this effect to the level of significance achievable in longitudinal studies. The similarities between our findings and those in the Alzheimer’s cohorts support the idea that the disease-related effects resemble an exaggerated form of healthy aging-related changes (Berg, 1985).

Fig. 5. Increases in fractional anisotropy (FA).

(a) FA is known to increase in the superior corona radiata in Alzheimer’s disease relative to healthy controls. Images adapted from (Douaud et al., 2011). (b) DTI-FWE results show a FAt increase with healthy aging in the same regions, as well as in the internal capsule, occurring during healthy aging. Increased FA in healthy aging cannot be detected without FWE as it is seemingly masked by increasing isotropic free water with age. This suggests that increased FA is not a unique symptom of Alzheimer’s disease, but may represent an exaggeration of a normal age-related effect that can be observed even without FWE. Images displayed in LAS (radiological) orientation with fill to increase clarity. Abbreviations: DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; FA, fractional anisotropy; FWE, free water elimination.

Focusing on the selective degeneration scenario, the corona radiata, internal capsule and corpus callosum all cross the corticospinal tract (Tuch et al., 2003) which has been suggested to be relatively spared in aging (Jang and Seo, 2015). Furthermore, at the crossings with the corona radiata and internal capsule, the diffusion tensors show that the principal fibre orientation is along the superior-inferior direction, paralleling the corticospinal tract. Degeneration of crossing fibres while the principal fibre remains intact could well explain the observed FAt increase with age (Supplementary Fig. S3). Indeed, the results of bedpostx tractography support this argument (Fig. 6). In particular, the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) crosses the corticospinal tract in the corona radiata, and the thalamic radiations (TRs) cross the corticospinal tract in the internal capsule. Both the SLF and TRs are thought to degenerate heavily with age while the corticospinal tract remains stable (Cox et al., 2016). This implies that the increase in free water with age does not only obscure microstructural changes in single fibre tracts, but also complicates the observation of changes at fibre crossings.

Fig. 6. Evidence of selective degeneration of crossing fibres with age in the internal capsule.

(a) Tractography studies in the literature (such as Hosey et al., 2008, as shown) show secondary thalamic radiations crossing the primary corticospinal tract in the internal capsule (red box). The white box demarcates a representative crossing scenario. (b) In the current study, the internal capsule exhibits a positive association of both tissue fractional anisotropy (FAt) and tissue mode of anisotropy (MOt) with age, which implies an increasingly linear tensor shape with age. (b) Bedpostx tractography suggests this increase in FAt and MOt with age may be due to selective degeneration of secondary crossing fibres: Secondary fibres exhibit greater decline with age than primary fibres in these regions. Abbreviations: FAt, tissue fractional anisotropy; MOt, tissue mode of anisotropy.

This is the first study to show the importance of free water on the measurement of age-related differences in WM microstructure. Partial-volume effects with CSF have been shown to influence DTI parameters (Alexander et al., 2001; Vos et al., 2011) with the fornix being particularly affected (Kaufmann et al., 2017). It was previously believed that since deep WM structures are further from CSF, age-related differences in DTI parameters in these regions would reflect true tissue microstructure (Madden et al., 2012). The FWE technique has previously only been applied to aging at a much smaller scale (N = 39) and confined to the fornix (Metzler-Baddeley et al., 2012) in which analogous results were found. Our study shows that age-related differences in the deep WM skeleton are in fact still greatly affected by free water despite their distance from the ventricles.

Furthermore, this study provides evidence that the free water fraction, f is a novel and useful measure of WM degeneration during healthy aging. Quantifying WM microstructural degeneration using tissue morphometry is not feasible as WM volume accounts for both WM fibres and extracellular water. Until now, arguably the best candidate in this regard has been diffusivity. However, the interpretation of age-related differences in MD is debatable, as MD also reflects restricted and hindered diffusion (Fig. 1), and these decrease with age, which may explain why MD only shows a moderate correlation with age. However, in this work, the free water fraction f is more strongly associated with age than any of the conventional or free water-corrected DTI parameters (Fig. 3), supporting the interpretation of the free water fraction as being mainly age-dependent interstitial water fraction. Notably, the structure of the free water fraction maps also supports the anterior-posterior hypothesis. We propose that f may be interpreted as the fraction of “degenerated tissue” within a voxel. That is, regions with large increases in f with age are likely to indicate microstructural degeneration.

This study was analyzed using tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) for the purpose of observing the spatial distribution of age-related differences in the white matter skeleton. A potential caveat to using TBSS in the study of aging is the likely prevalence of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) at older ages, which can lower FA values and thus reduce the amount of white matter included in the skeleton. Future work may assess the distribution of age-related differences outside the skeleton through voxel-based morphometry (VBM), or more localized analyses can also be conducted within specific tracts or regions of interest.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the specificity of DTI parameters with underlying pathology is not complete, and full validation would require histological data from the same participants who underwent diffusion MRI acquisitions. However, removing the extracellular component with FWE improves the specificity of the DTI parameters to processes that occur within the tissue. We computed free water fraction from standard single-shell diffusion MRI acquisitions, requiring a regularizer to fit the free water model. Although the computation of f with single-shell FWE has been found to be comparable with using the multi-shell approach (Pasternak et al., 2012), applying FWE to multi-shell acquisitions in future studies can potentially uncover subtle age-related differences that are “smoothed out” in single-shell FWE. It should be noted that our observed increase in f with age was similar to increased isotropic volume fraction (isoVF) with age observed with the multi-shell NODDI model (Billiet et al., 2015; Cox et al., 2016). While preliminary results suggest that free water estimates in FWE-DTI and NODDI are correlated (van Bruggen et al., 2013), a thorough comparison of single-shell and multi-shell approaches to free water mapping is part of our future work. That being said, it should be noted that in the context of aging we are mainly interested in the age-related differences rather than in the absolute free water fractions, and our results clearly show the potential of single-shell FWE to provide meaningful insight into age-related changes. At the same time, FWE does not eliminate all extracellular water. That is, in relatively preserved regions with stable axonal integrity and myelin packing density with age, much of the increased extracellular water may still encounter restrictions and is thus not considered “free”. The observation of increased AD in such regions, even after FWE, may point to the residual extracellular water masking the effect of intracellular debris accumulation. Conversely, in regions known to degenerate more heavily with age, the reduction in WM packing density allows more interstitial water to undergo unrestricted diffusion, and FWE seemingly eliminates this to reveal ADt decreases. Related to the above point, longer diffusion times allow more time for water to hit boundaries, potentially reducing the value of f. The effect of diffusion time on the estimated f values has yet to be undertaken and is part of our future work.

Two more points about this study should be noted. First, a main purpose of this article is to demonstrate the value of retrospectively re-examining any single-shell DTI dataset, and the dataset we assessed was not specifically acquired for the purpose of free water elimination. The b-value of 700mm2/s is fairly low. While a low b-value is actually preferable for identifying free water, it is not optimal for fitting the bedpostx model. In spite of this, we still chose to use bedpostx to provide context for our interpretation of increased FAt with age rather than strictly relying on evidence of selective degeneration in the literature. A more thorough understanding of crossing fibres in single-shell datasets can be better done for acquisitions with higher b-values and using advanced analysis such as multi-tissue deconvolution (Mito et al., 2018). Additionally, a blip-up/blip-down phase-encode acquisition could have enhanced echo-planar imaging (EPI) distortion correction (Andersson et al., 2003) and eddy current distortions could be corrected with FSL’s recent tool EDDY (Andersson and Sotiropoulos, 2016) rather than eddy_correct in future work. For studies beginning to acquire data, we would recommend acquiring multiple shells with blip-up/blip-down phase-encode acquisition for the most optimal data quality. Nevertheless, our study displayed the potential to harness the power of an existing standard DTI dataset.

Second, it should be noted that the schematic of white matter we presented (Fig. 1) is overly simplistic. In addition to the presence of glial cells, blood vessels also line white matter fibres along the principal direction (Aslan et al., 2011) and the calculation of free water has been shown to be sensitive to plasma, potentially increasing the value of f (Rydhog et al., 2017). Histological studies support the notion that increased free water with age reflects enlarged interstitial spaces (Meier-Ruge et al., 1992) as opposed to increased vasodilation, as vasodilation is known to decline with age (Westby et al., 2011). Lymphatic flow is also known to slow down with age (Kress et al., 2014) as plasma accumulates debris across the lifespan (Abd-Allah et al., 2004) so flow is unlikely to significantly contribute to the increase in free water with age. However, leakage due to a disruption of the blood-brain barrier at older ages (Sonntag et al., 2011) may contribute to the observed age-related differences in f

Conclusion

In this work, we determined the value of re-examining DTI data to account for free water in extracellular spaces. We demonstrated the utility of mapping free water using standard single-shell DTI data, and free water fraction was found to be a more robust indicator of age than commonly used DTI parameters. Eliminating free water allowed for the observation of trends consistent with documented histological findings of axonal and myelin damage. Moreover, while selective degeneration of crossing fibres has commonly been observed through increased FA in Alzheimer’s disease, this effect was previously only seen in healthy aging with a cross-sectional study of 5,000 participants and a longitudinal study of 501 participants. This study provides the first evidence in support of this in healthy aging using cross-sectional single-shell DTI data with a more modest sample size. Our work suggests that FWE reduces variability in common DTI parameters to allow for observation of finer microstructural phenomena. Continuing to re-examine data by accounting for free water can potentially yield novel insight in ongoing DTI studies of brain aging.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Free water is found to positively correlate with age throughout the white matter

Accounting for free water alters age-related differences in DTI metrics

Free-water corrected DTI metrics provide more tissue-specific measures of aging

Such free water analysis can be performed on any standard DTI dataset

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Saad Jbabdi (Oxford) and Jennifer Campbell (McGill) for helpful discussions on the manuscript. This work was supported by NSERC Discovery Grant RGPIN #418443, NIH grants R01MH108574, R01AG042512, P41EB015902, R01NR010827, NS042861 and NS058793, CIHR Operating Grant FRN #126164 and CIHR Foundation Grant FRN #148398.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abd-Allah NM, Hassan FH, Esmat AY, Hammad SA, 2004. Age dependence of the levels of plasma norepinephrine, aldosterone, renin activity and urinary vanillylmandelic acid in normal and essential hypertensives. Biol. Res 37, 95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albi A, Pasternak O, Minati L, Marizzoni M, Bartres-Faz D, Bargallo N, Bosch B, Rossini PM, Marra C, Muller B, Fiedler U, Wiltfang J, Roccatagliata L, Picco A, Nobili FM, Blin O, Sein J, Ranjeva J-P, Didic M, Bombois S, Lopes R, Bordet R, Gros-Dagnac H, Payoux P, Zoccatelli G, Alessandrini F, Beltramello A, Ferretti A, Caulo M, Aiello M, Cavaliere C, Soricelli A, Parnetti L, Tarducci R, Floridi P, Tsolaki M, Constantinidis M, Drevelegas A, Frisoni G, Jovicich J, PharmaCog Consortium, 2017. Free water elimination improves test-retest reproducibility of diffusion tensor imaging indices in the brain: A longitudinal multisite study of healthy elderly subjects. Hum. Brain Mapp 38, 12–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander AL, Hasan KM, Lazar M, Tsuruda JS, Parker DL, 2001. Analysis of partial volume effects in diffusion-tensor MRI. Magn. Reson. Med 45, 770–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JLR, Skare S, Ashburner J, 2003. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage 20, 870–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JLR, Sotiropoulos SN, 2016. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage 125, 1063–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan S, Huang H, Uh J, Mishra V, Xiao G, van Osch MJP, Lu H, 2011. White matter cerebral blood flow is inversely correlated with structural and functional connectivity in the human brain. Neuroimage 56, 1145–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser PJ, Pajevic S, Pierpaoli C, Duda J, Aldroubi A, 2000. In vivo fiber tractography using DT-MRI data. Magn. Reson. Med 44, 625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendlin BB, Fitzgerald ME, Ries ML, Xu G, Kastman EK, Thiel BW, Rowley HA, Lazar M, Alexander AL, Johnson SC, 2010. White matter in aging and cognition: a cross-sectional study of microstructure in adults aged eighteen to eighty-three. Dev. Neuropsychol 35, 257–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IJ, Madden DJ, Vaidya CJ, Howard DV, Howard JH Jr., 2010. Age-related differences in multiple measures of white matter integrity: A diffusion tensor imaging study of healthy aging. Hum. Brain Mapp 31, 378–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamino M, Pasternak O, Farmer M, Shenton ME, Hamilton JP, 2016. Applying a free-water correction to diffusion imaging data uncovers stress-related neural pathology in depression. Neuroimage Clin 10, 336–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg L, 1985. Does Alzheimer’s disease represent an exaggeration of normal aging? Arch. Neurol 42, 737–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billiet T, Vandenbulcke M, Madler B, Peeters R, Dhollander T, Zhang H, Deprez S, Van den Bergh BRH, Sunaert S, Emsell L, 2015. Age-related microstructural differences quantified using myelin water imaging and advanced diffusion MRI. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 2107–2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Rosas HD, Salat DH, 2013. The relationship between cortical blood flow and subcortical white-matter health across the adult age span. PLoS One 8, e56733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox SR, Ritchie SJ, Tucker-Drob EM, Liewald DC, Hagenaars SP, Davies G, Wardlaw JM, Gale CR, Bastin ME, Deary IJ, 2016. Ageing and brain white matter structure in 3,513 UK Biobank participants. Nat. Commun 7, 13629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DG, Schmitt FA, Wekstein DR, Markesbery WR, 1999. Alzheimer neuropathologic alterations in aged cognitively normal subjects. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 58, 376–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SW, Dennis NA, Buchler NG, White LE, Madden DJ, Cabeza R, 2009. Assessing the effects of age on long white matter tracts using diffusion tensor tractography. Neuroimage 46, 530–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot M, Cremers LGM, Ikram MA, Hofman A, Krestin GP, van der Lugt A, Niessen WJ, Vernooij MW, 2016. White Matter Degeneration with Aging: Longitudinal Diffusion MR Imaging Analysis. Radiology 279, 532–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan NT, Engvig A, Persson K, Alnæs D, Kaufmann T, Rokicki J, Córdova-Palomera A, Moberget T, Brækhus A, Barca ML, Engedal K, Andreassen OA, Selbæk G, Westlye LT, 2017. Dissociable diffusion MRI patterns of white matter microstructure and connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Sci. Rep 7, 45131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douaud G, Jbabdi S, Behrens TEJ, Menke RA, Gass A, Monsch AU, Rao A, Whitcher B, Kindlmann G, Matthews PM, Smith S, 2011. DTI measures in crossing-fibre areas: increased diffusion anisotropy reveals early white matter alteration in MCI and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 55, 880–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elobeid A, Libard S, Leino M, Popova SN, Alafuzoff I, 2016. Altered Proteins in the Aging Brain. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 75, 316–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis DB, Kindlmann G, 2006. Orthogonal tensor invariants and the analysis of diffusion tensor magnetic resonance images. Magn. Reson. Med 55, 136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, 2012. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 62, 774–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head D, Buckner RL, Shimony JS, Williams LE, Akbudak E, Conturo TE, McAvoy M, Morris JC, Snyder AZ, 2004. Differential vulnerability of anterior white matter in nondemented aging with minimal acceleration in dementia of the Alzheimer type: evidence from diffusion tensor imaging. Cereb. Cortex 14, 410–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosey TP, Harding SG, Carpenter TA, Ansorge RE, Williams GB, 2008. Application of a probabilistic double-fibre structure model to diffusion-weighted MR images of the human brain. Magn. Reson. Imaging 26, 236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SH, Seo JP, 2015. Aging of corticospinal tract fibers according to the cerebral origin in the human brain: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurosci. Lett 585, 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jbabdi S, Behrens TEJ, Smith SM, 2010. Crossing fibres in tract-based spatial statistics. Neuroimage 49, 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S, 2002. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 17, 825–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann L-K, Baur V, Hanggi J, Jancke L, Piccirelli M, Kollias S, Schnyder U, Pasternak O, Martin-Soelch C, Milos G, 2017. Fornix Under Water? Ventricular Enlargement Biases Forniceal Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging Indices in Anorexia Nervosa. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging 2, 430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, Floriach-Robert M, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Dickson DW, Johnson KA, Petersen LE, McDonald WC, Braak H, Petersen RC, 2003. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 62, 1087–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress BT, Iliff JJ, Xia M, Wang M, Wei HS, Zeppenfeld D, Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Liew JA, Plog BA, Ding F, Deane R, Nedergaard M, 2014. Impairment of paravascular clearance pathways in the aging brain. Ann. Neurol 76, 845–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampinen B, Szczepankiewicz F, Mårtensson J, van Westen D, Sundgren PC, Nilsson M, 2017. Neurite density imaging versus imaging of microscopic anisotropy in diffusion MRI: A model comparison using spherical tensor encoding. Neuroimage 147, 517–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, Gee M, Camicioli R, Wieler M, Martin W, Beaulieu C, 2012. Diffusion tensor imaging of white matter tract evolution over the lifespan. Neuroimage 60, 340–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden DJ, Bennett IJ, Burzynska A, Potter GG, Chen N-K, Song AW, 2012. Diffusion tensor imaging of cerebral white matter integrity in cognitive aging. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1822, 386–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier-Hein KH, Westin C-F, Shenton ME, Weiner MW, Raj A, Thomann P, Kikinis R, Stieltjes B, Pasternak O, 2015. Widespread white matter degeneration preceding the onset of dementia. Alzheimers. Dement 11, 485–493.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandl RCW, Pasternak O, Cahn W, Kubicki M, Kahn RS, Shenton ME, Hulshoff Pol HE, 2015. Comparing free water imaging and magnetization transfer measurements in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 161, 126–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marner L, Nyengaard JR, Tang Y, Pakkenberg B, 2003. Marked loss of myelinated nerve fibers in the human brain with age. J. Comp. Neurol 462, 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier-Ruge W, Ulrich J, Bruhlmann M, Meier E, 1992. Age-related white matter atrophy in the human brain. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 673, 260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler-Baddeley C, O’Sullivan MJ, Bells S, Pasternak O, Jones DK, 2012. How and how not to correct for CSF-contamination in diffusion MRI. Neuroimage 59, 1394–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KL, Alfaro-Almagro F, Bangerter NK, Thomas DL, Yacoub E, Xu J, Bartsch AJ, Jbabdi S, Sotiropoulos SN, Andersson JLR, Griffanti L, Douaud G, Okell TW, Weale P, Dragonu I, Garratt S, Hudson S, Collins R, Jenkinson M, Matthews PM, Smith SM, 2016. Multimodal population brain imaging in the UK Biobank prospective epidemiological study. Nat. Neurosci 19, 1523–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mito R, Raffelt D, Dhollander T, Vaughan DN, Tournier J-D, Salvado O, Brodtmann A, Rowe CC, Villemagne VL, Connelly A, 2018. Fibre-specific white matter reductions in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Brain. 10.1093/brain/awx355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann H, Kotter MR, Franklin RJM, 2009. Debris clearance by microglia: an essential link between degeneration and regeneration. Brain 132, 288–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofori E, Pasternak O, Planetta PJ, Burciu R, Snyder A, Febo M, Golde TE, Okun MS, Vaillancourt DE, 2015. Increased free water in the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s disease: a single-site and multi-site study. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 1097–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis NG, Martin KM, Mustafa MH, Wilkinson ID, Griffiths PD, Huang CL-H, Woodruff PWR, 2002. Study of the effect of CSF suppression on white matter diffusion anisotropy mapping of healthy human brain. Magn. Reson. Med 48, 394–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Shenton ME, Westin C-F, 2012. Estimation of extracellular volume from regularized multi-shell diffusion MRI. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv 15, 305–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Sochen N, Basser PJ, 2010. The effect of metric selection on the analysis of diffusion tensor MRI data. Neuroimage 49, 2190–2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Sochen N, Gur Y, Intrator N, Assaf Y, 2009. Free water elimination and mapping from diffusion MRI. Magn. Reson. Med 62, 717–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, 2002. The effects of normal aging on myelin and nerve fibers: a review. J. Neurocytol 31, 581–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Adalsteinsson E, Sullivan EV, 2005. Frontal circuitry degradation marks healthy adult aging: Evidence from diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage 26, 891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierpaoli C, Jones DK, 2004. Removing CSF contamination in brain DT-MRIs by using a two-compartment tensor model. Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med 11, 1215. [Google Scholar]

- Piguet O, Double KL, Kril JJ, Harasty J, Macdonald V, McRitchie DA, Halliday GM, 2009. White matter loss in healthy ageing: a postmortem analysis. Neurobiol. Aging 30, 1288–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotshenker S, 2011. Wallerian degeneration: the innate-immune response to traumatic nerve injury. J. Neuroinflammation 8, 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydhog AS, Szczepankiewicz F, Wirestam R, Ahlgren A, Westin C-F, Knutsson L, Pasternak O, 2017. Separating blood and water: Perfusion and free water elimination from diffusion MRI in the human brain. Neuroimage 156, 423–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safaiyan S, Kannaiyan N, Snaidero N, Brioschi S, Biber K, Yona S, Edinger AL, Jung S, Rossner MJ, Simons M, 2016. Age-related myelin degradation burdens the clearance function of microglia during aging. Nat. Neurosci 19, 995–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, 2002. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum. Brain Mapp. 17, 143–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, Watkins KE, Ciccarelli O, Cader MZ, Matthews PM, Behrens TEJ, 2006. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage 31, 1487–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM, 2004. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23 Suppl 1, S208–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag WE, Eckman DM, Ingraham J, Riddle DR, 2011. Regulation of Cerebrovascular Aging, in: Riddle DR (Ed.), Brain Aging: Models, Methods, and Mechanisms. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton (FL). [Google Scholar]

- Steventon JJ, Trueman RC, Rosser AE, Jones DK, 2016. Robust MR-based approaches to quantifying white matter structure and structure/function alterations in Huntington’s disease. J. Neurosci. Methods 265, 2–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Pfefferbaum A, 2006. Diffusion tensor imaging and aging. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 30, 749–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Nyengaard JR, Pakkenberg B, Gundersen HJ, 1997. Age-induced white matter changes in the human brain: a stereological investigation. Neurobiol. Aging 18, 609–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teipel SJ, Grothe MJ, Filippi M, Fellgiebel A, Dyrba M, Frisoni GB, Meindl T, Bokde ALW, Hampel H, Kloppel S, Hauenstein K, EDSD study group, 2014. Fractional anisotropy changes in Alzheimer’s disease depend on the underlying fiber tract architecture: a multiparametric DTI study using joint independent component analysis. J. Alzheimers. Dis 41, 69–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuch DS, Reese TG, Wiegell MR, Wedeen VJ, 2003. Diffusion MRI of complex neural architecture. Neuron 40, 885–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuozzo C, Lyall AE, Pasternak O, James ACD, Crow TJ, Kubicki M, 2017. Patients with chronic bipolar disorder exhibit widespread increases in extracellular free water. Bipolar Disord. 10.1111/bdi.12588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bruggen T, Zhang H, Pasternak O, Meinzer HP, Stieltjes B, Fritzsche KH, 2013. Free-water elimination for assessing microstructural gray matter pathology—with application to Alzheimer’s Disease. Proc. Int. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med 21, 0790. [Google Scholar]

- Vos SB, Jones DK, Viergever MA, Leemans A, 2011. Partial volume effect as a hidden covariate in DTI analyses. Neuroimage 55, 1566–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westby CM, Weil BR, Greiner JJ, Stauffer BL, DeSouza CA, 2011. Endothelin-1 vasoconstriction and the age-related decline in endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in men. Clin. Sci 120, 485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston GP, 2012. The physical and biological basis of quantitative parameters derived from diffusion MRI. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg 2, 254–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T, 2016. Ageing, neurodegeneration and brain rejuvenation. Nature 539, 180–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon B, Shim Y-S, Lee K-S, Shon Y-M, Yang D-W, 2008. Region-specific changes of cerebral white matter during normal aging: a diffusion-tensor analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr 47, 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Schneider T, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Alexander DC, 2012. NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage 61, 1000–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.