Abstract

Understanding large carnivore occurrence patterns in anthropogenic landscapes adjacent to protected areas is central to developing actions for species conservation in an increasingly human-dominated world. Among large carnivores, leopards (Panthera pardus) are the most widely distributed felid. Leopards occupying anthropogenic landscapes frequently come into conflict with humans, which often results in leopard mortality. Leopards’ use of anthropogenic landscapes, and their frequent involvement with conflict, make them an insightful species for understanding the determinants of carnivore occurrence across human-dominated habitats. We evaluated the spatial variation in leopard site use across a multiple-use landscape in Tanzania’s Ruaha landscape. Our study region encompassed i) Ruaha National Park, where human activities were restricted and sport hunting was prohibited; ii) the Pawaga-Idodi Wildlife Management Area, where wildlife sport hunting, wildlife poaching, and illegal pastoralism all occurred at relatively low levels; and iii) surrounding village lands where carnivores and other wildlife were frequently exposed to human-carnivore conflict related-killings and agricultural habitat conversion and development. We investigated leopard occurrence across the study region via an extensive camera trapping network. We estimated site use as a function of environmental (i.e. habitat and anthropogenic) variables using occupancy models within a Bayesian framework. We observed a steady decline in leopard site use with downgrading protected area status from the national park to the Wildlife Management Area and village lands. Our findings suggest that human-related activities such as increased livestock presence and proximity to human households exerted stronger influence than prey availability on leopard site use, and were the major limiting factors of leopard distribution across the gradient of human pressure, especially in the village lands outside Ruaha National Park. Overall, our study provides valuable information about the determinants of spatial distribution of leopards in human-dominated landscapes that can help inform conservation strategies in the borderlands adjacent to protected areas.

1. Introduction

As apex predators, large-bodied mammals of the order Carnivora can exert important influence on regulation of trophic interactions and the maintenance of ecosystem functions [1, 2]. Large carnivores, besides their intrinsic value as species [3], are also important revenue-generators for a multimillion-dollar ecotourism and sport hunting industry that contributes to national economies as well as the conservation and management of wildlife and wilderness, particularly in Africa [4, 5]. Despite clear ecological, economic, and intrinsic value, large carnivore populations are threatened globally, with 24 of the remaining 31 species documented to be declining [1]. Such population losses are attributable to habitat conversion, human persecution, prey depletion, unsustainable hunting, and exploitation for body parts [1, 6, 7]. Human population growth and urbanization around protected areas, especially in the sub-Saharan African countries [8, 9], present imminent challenges for carnivore conservation. For example, mortality is higher along the boundaries of protected areas where large carnivores risk being killed preventatively or in retaliation to predation events that can cause substantial financial loss to people’s livelihoods [10–12]. The habitats associated with this human-carnivore interface can function as population sinks, whereby the high human-induced large carnivore offtake can “drain” populations from the bordering protected areas and compromise population persistence [11, 12]. However, as large carnivores are often wide-ranging and maintain large home ranges [1, 13], they usually rely on these peripheral human-dominated lands around protected areas [11, 14, 15] that can provide important habitats for these species. For instance, 68% of the most suitable habitats for leopards in South Africa have been estimated to occur outside national parks and protected areas, in areas of human occupation and subject to habitat conversion [16]. Thus, these human-dominated habitats can be essential to the conservation of large carnivore populations [10, 11, 17, 18]. Accordingly, determining the extent to which large carnivores can occupy areas of increasing human pressure, such as those represented by human encroachment of wildlands and agro-pastoralism, is of major importance for their conservation.

Among large carnivores, leopards (Panthera pardus) are the most widespread felid species, occupying the most diverse habitat types including deserts, forests, and savannahs [19]. Leopards’ behavioural flexibility and dietary plasticity facilitates their successful occupation of highly modified and heavily disturbed human-dominated landscapes, given adequate human tolerance to their presence in such habitats [20, 21]. For instance, even in densely populated areas (400 people/km2) leopards can live alongside people by mostly feeding on livestock and domestic dogs, and finding refuge in crops and agricultural lands [20, 21]. Despite such ecological plasticity, leopards are threatened by rampant habitat destruction and fragmentation, prey depletion induced by bushmeat poaching and overgrazing, unsustainable harvest by sport hunting and to attend demands for body parts, and conflict-related mortality [19, 22, 23]. As a result, leopard populations have experienced >30% global range contraction in the past 20 years. In Africa, leopards have lost 48–67% of their historical distribution, with the most pronounced reductions in northern and western Africa [19]. The species is expected to undergo further population decline across its overall Sub-Saharan African range given the observed high rate of prey depletion [22] and habitat loss induced by increasing human population in the next 50 years [23].

Tanzania is one of the most important countries for leopard conservation in Africa, where its vast array of national parks and game reserves protects substantial portions of the leopard’s extant range [19]. Leopards represent an important economic asset for Tanzania, as the species is among the most exported trophy species; in 2008 hunting of leopards and other mammalian megafauna contributed to a USD 56.3 million revenue for hunting operators and governments [4]. Despite the ecological and economic importance of leopards, the current lack of empirical field data on leopard ecology hinders the development of effective conservation strategies designed to protect the species in Tanzania [24, 25].

In this study, we investigated the factors affecting the probability of leopard site use at the interface of protected and unprotected habitat in southern Tanzania’s Ruaha landscape. Our study area encompassed the eastern portions of Ruaha National Park, the adjacent semi-protected Pawaga-Idodi Wildlife Management Area (WMA), and unprotected village lands. Specifically, we assessed spatial variation in leopard site use in response to (i) anthropogenic disturbance, as indicated by distance to households and livestock number, (ii) the availability of primary prey species, and (iii) proximity to water sources. Documenting the factors associated with carnivore site use is central to prioritising conservation efforts for these species. The methods and framework presented in this study provide a timely and useful tool that is going to become ever more important in increasingly human-modified protected to unprotected habitat interfaces.

2. Material and methods

Ethics statement

Data collection was based on the use of camera traps, a non-invasive method that does not involve contact with the study species, nor interfere with their natural behaviour. Fieldwork was carried out under research permit no. TWRI/TST/65/VOL.VII/85/146 to LA, issued by the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) and the Commission for Research and Technology (COSTECH).

The Ruaha landscape

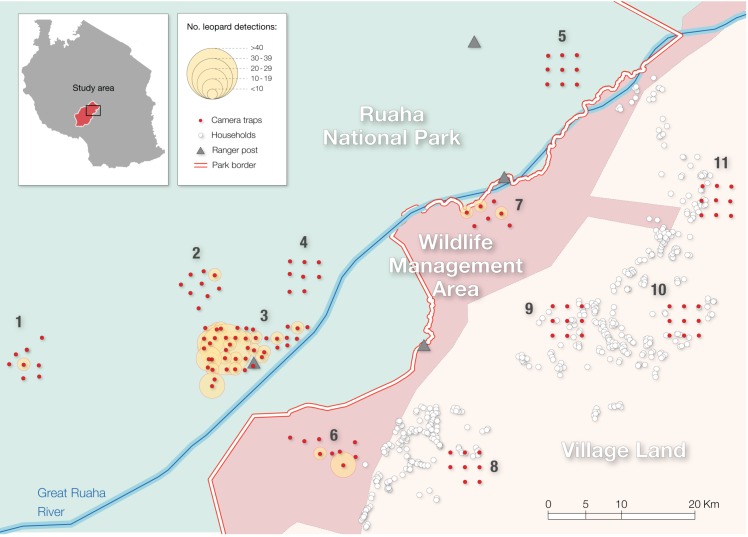

We conducted our study in southern Tanzania across the Ruaha landscape (Fig 1). The Ruaha landscape spans over 50 000 km2 and supports substantial populations of large carnivores. For this reason, the landscape has been listed by the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute as a priority for carnivore research and conservation [25]. Ruaha National Park is one of the largest national parks in Africa, spanning over 20 226 km2. Trophy hunting of wildlife is prohibited within the park and in the village lands, but is permitted in limited sections of the WMA. In the village lands, large carnivores are exposed to anthropogenic disturbance, including intense human-carnivore conflict, bushmeat snaring, and indiscriminate poisoning. The village lands are inhabited by over 60 000 people divided among 21 villages [26]. The predominant livelihood is agropastoralism [27]. Donkeys, goats, and cattle are the most commonly kept domestic livestock. Although no official numbers for livestock abundance are available for this area, the overall Iringa region, within which Ruaha National Park sits, contains a fifth of Tanzania’s total domestic animals, with > 620 000 livestock and > 1.5 million poultry [27]. Attitudes towards large carnivores among village members tend to be negative, motivated by both real and perceived carnivore depredation of livestock [28]. Consequently, large carnivores experience high rates of human-induced mortality in this landscape. From 2010–2016, 100 lions and other large carnivores were killed by people. Given the intense conflict and mortality rates, and the paucity of information about the spatial distribution of large carnivores in these areas [24, 25], it is imperative to improve understanding of the ecological and anthropogenic factors influencing large carnivore occurrence in these areas.

Fig 1. Spatial distribution of the camera-trap stations (red shaded circles) across the Ruaha landscape.

1–11 represents sampling areas: 1. Mdonya; 2. Kwihala; 3. Msembe; 4. Mwagusi; 5. Lunda-Ilolo; 6. Pawaga; 7. Lunda; 8. Idodi; 9. Malinzanga; 10. Nyamahana; 11. Magosi. The yellow shaded circles represent the number of independent detections of leopards (Panthera pardus) at each camera-trap station (> 5 minutes between detection).

The climate of the region is semi-arid to arid, with an average annual precipitation of 500 mm, and a bimodal rainy season from December to January and March to April [29]. The vegetation cover is a mosaic of semi-arid savannahs and northerly Zambesian miombo woodlands [30]. The village lands are primarily covered by agricultural fields (mostly rice and maize crops), and livestock grazing areas. The Greater Ruaha River is the main water source in the study area, especially during the dry season. This river provides key resources for wildlife, attracting species towards the park borders with the WMA and village land.

Leopard data

To document leopard site use, we deployed 127 non-baited, remotely triggered, single camera-trap stations (CTs) that sampled 11 areas across the Ruaha landscape during the dry seasons of 2014 and 2015. In 2014, we placed 42 Reconyx HC500 CTs along animal trails, and sampled the Msembe area, near the park headquarters, where there is low anthropogenic pressure [31]. In 2015, we used 85 Bushnell Scoutguard CTs and extended sampling to other 10 areas, including four sampling areas in RNP, two in the WMA, and four in the village lands (Fig 1). We used a pseudostratified method for deploying our CTs, ensuring a minimum 1.5–2 km distance between stations, and 15–20 km distance between sampling areas whenever possible. The sampling areas were distributed across a range of distances from the border of the national park (0–10 km; 10–20 km; >30 km) to enable examining potential spatial variation in leopard occurrence (Fig 1). We set the CTs facing animal trails when the pre-defined GPS coordinates were found within 5 meters from the nearest open path showing signs of animal use. We adopted this design so as to increase detection of more elusive species [32]. All the CTs were placed in trees or poles at a height of 0.3–0.5 meters off the ground. We visited the CTs every 30–50 days to retrieve data and service the traps. Though certain regions of the national park were inaccessible (especially in the road-less southern sections), our CTs placement intended to capture substantial habitat heterogeneity observed across the landscape.

We pooled the overall data and analysed it in a single-season framework, as previous studies conducted in the central areas of the Ruaha National Park have found large carnivores to have similar site use patterns across the dry seasons of 2014 and 2015 [31]. We collapsed the temporal extent of the sampling into seven days bin intervals, across a 32-week survey (~210 days) period. This timeframe has been chosen to ensure continued sampling through the whole dry season. Given the long duration of our survey across the whole dry seasons, we were unable to meet the population closure assumption of the occupancy model [33–35]. However, such assumption can be relaxed when changes in the population of interested are assumed to happen randomly during the survey period [34], which may the case with our extended sampling period. The relaxation of the population closure assumption requires changing the interpretation of the occupancy parameter from true occupancy to proportion of site used by the species, which originally was our main interest. Thus, in this study, site use equates to the probability that a given site was used during the overall survey period, rather than the probability of continuous site occupation [35].

The leopard occurrence data used for the model can be found freely available at https://github.com/labade/GitHub/tree/master/leop_occu_data.

Environmental covariates

We modelled leopard site use as a function of five environmental covariates known to influence leopard habitat selection (Table 1) [36–40]. We calculated the distance to Great Ruaha River and distance to household covariates as rasters at a resolution of 500 m (S1 Fig). We generated the rasters in QGIS 2.6.0 [41] from freely available geoprocessed satellite imagery and data collected by University of Oxford’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Ruaha Carnivore Project. We developed a primary wild prey availability covariate for leopards. To do so, we calculated a temporal catch-per unit effort (CPUE) index of prey availability for each CTs based on the number of independent records for the main five leopard prey species [42]. Prey species included bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus), common duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia), greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), impala (Aepyceros melampus), and warthog (Phacochoerus africanus). We calculated the CPUE by multiplying the number of independent events at each CTs by the species average mass, divided by the CTs sampling effort, and standardised per 100 camera trap days [14]. Prey mass was based on standard reference guides [43]. The CPUE index is often used in the fisheries industry to assess stock abundance, and provide information for monitoring the effects of harvesting on populations [44, 45].The concept behind CPUE is that the size of the catch from a population should increase when population density or effort increases [46]. Thus, in principle, CPUE could serve as an abundance index, and be used to detect variation in numbers as in abundance itself. The concept has been used in the studies of carnivore live trapping [47], bushmeat harvesting and poaching [48, 49], and to estimate prey biomass in camera-trapping and occupancy studies [50]. We also calculated a livestock presence covariate by summing the total independent livestock detections at each CTs. Livestock species included cattle, goats, and donkeys. We pooled these species because the objective was to assess the overall disturbance potential of livestock grazing on leopard site use, irrespective of the livestock species. We considered independent detection events for leopard, prey and livestock as those with > 5 minutes between records [14].

Table 1. Covariates and corresponding expected influence on the estimates of leopard site use and detection in the Ruaha landscape, southern Tanzania, during the dry seasons of 2014–2015.

Ψ: Estimated probability of site use; p: probability of detection, given site use. CPUE: catch-per unit effort index of prey availability for each camera-trap station based on the number of independent records for the main five leopard prey species [42] photographed during the survey.

| Covariates | Model type | Expected influence |

|---|---|---|

| Livestock presence | Ψ | - |

| Distance to Greater Ruaha River | Ψ | + |

| Distance to household | Ψ | + |

| Prey availability (CPUE) | Ψ | + |

| Trail type | p | + |

Given that trail types have been found to influence on probability of carnivore detection in this study region [31], we evaluated the effect of trail type [animal trails (AT); no-trails (NT); human-made roads (RD)] on leopard detection probability.

Prior to model fitting, we standardized (z-score) all covariates [51], and assessed predictor collinearity using Pearson correlation and variance inflation factor tests. All the covariates used in the models were those minimally correlated (Pearson <0.7, VIF <3 [52]; S1 and S2 Tables.).

Model analyses and averaging

We used temporally replicated surveys (i.e. weeks) to estimate the latent, unobserved probability of site use of each CT, Zi, where Zi = 1 if site i is occupied and 0 otherwise. We used the replicate surveys to estimate detection probability, pi,j, where pi,j is the probability that leopards are detected at site i during replicate j, given use of that site (i.e., Zi = 1) [33, 53]. We fit the model with a random intercept at the level of each of the 11 areas sampled in the study [54, 55] to minimise potential spatial autocorrelation among model residuals (S2 Fig). Our final model to estimate leopard site use was implemented as follows:

| (1) |

where Ψi represents the probability of leopard site use at the ith CT, αarea represents a random intercept indexed by sampling area with estimated hyperparameters μ (mean) and τ2 (variance), and α1,2…5 represent the influence of associated covariates at the ith CT (Table 1).

The final detection model was implemented as follows:

| (2) |

where pi,j represents the probability of detection at the ith CT during survey j given that a site is used (i.e., Zi = 1), β0 is the intercept, and βk represents the effect of the kth trail type (k = 3) on leopard detection at each CT, with animal trail (AT) as the reference category.

We implemented and analysed the models using a Bayesian framework and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations in R v.2.13.0 [56] and JAGS [57] through the package ‘R2jags’ [58]. We estimated the degree of support for the effect of each covariate on site use through the Bayesian inclusion parameter wc [59], which had a Bernoulli distribution and an uninformative prior probability of 0.5. The posterior probability of wc corresponds to the estimated probability of any given covariate (‘C’) to be included in the best model of a set of 2C candidate models [14, 55, 60]. We calculated model-averaged estimates for the covariate coefficients over the global models from MCMC posterior histories, as described by Royle & Dorazio [60]. We used uninformative uniform priors for all covariates and implemented the models using three chains of 500 000 iterations each, discarding the first 50 000 as burn-in, and thinned the posterior chains by 10. We assessed the model convergence by ensuring R-hat values for all parameters was <1.1 [61].

3. Results

We recorded a total of 232 independent leopard events over 12 987 camera-trap days at 42 of the 127 CTs (33%). We recorded 197 leopard detections at 36 out of 77 CTs in the national park, 35 detections at 6 out of 16 CTs in WMA, and no detections at the 35 CTs installed in the village lands, despite the consistent sampling effort in this area (Fig 1; Table 2).

Table 2. Sampling effort per area in the Ruaha landscape, southern Tanzania.

CT effort (days): Number of active days of survey.

| Land-management | Area | CT effort (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kwihala | 196 | ||

| Lunda-Ilolo | 196 | ||

| National Park | Mdonya | 226 | |

| Msembe | 7,447 | ||

| Mwagusi | 173 | ||

|

Lunda |

867 | ||

| Wildlife Management Area | Pawaga | 738 | |

|

Idodi |

674 | ||

| Village land | Magosi | 656 | |

| Malinzanga | 718 | ||

| Nyamahana | 1,059 | ||

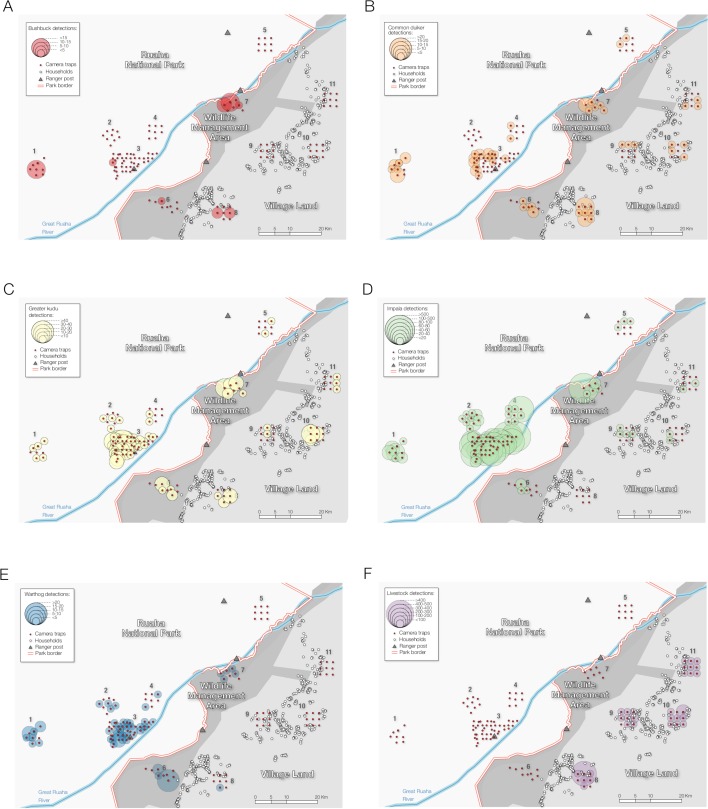

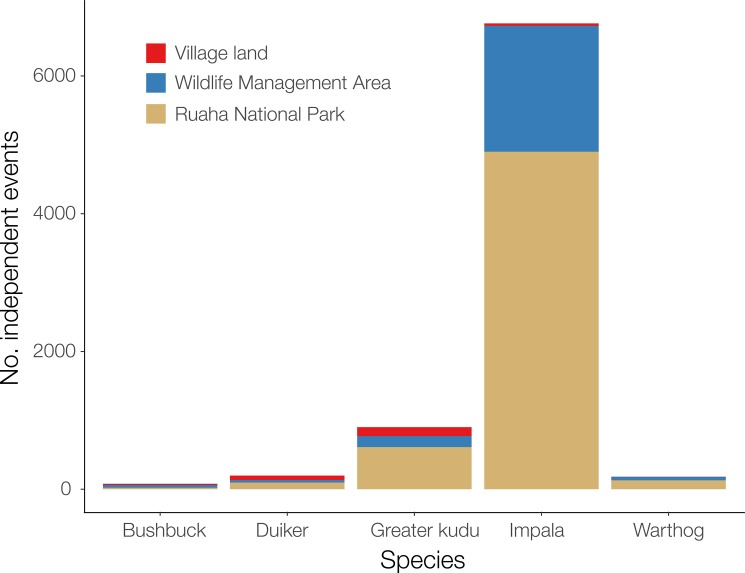

We recorded a total of 8 120 independent detections of the primary prey of leopards (Figs 2 and 3). We observed spatial variation in the number of primary prey detections, with a total of 5 766 independent prey records in the national park, 2 116 in the WMA, and 238 in the village lands (Fig 3). We registered 2 811 independent events of livestock in 32 out of 35 village land CTs.

Fig 2. Independent detections of the main leopard prey species at each camera-trap station.

A. Bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus); B. Common duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia); C. Greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros); D. Impala (Aepyceros melampus); E. Warthog (Phacochoerus africanus); F. Livestock. 1–11 represents sampling areas: 1. Mdonya; 2. Kwihala; 3. Msembe; 4. Mwagusi; 5. Lunda-Ilolo; 6. Pawaga; 7. Lunda; 8. Idodi; 9. Malinzanga; 10. Nyamahana; 11. Magosi.

Fig 3. Variation in prey detection across the gradient of anthropogenic pressure in the Ruaha landscape.

Independent events (> 5 min interval between detection). Bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus); Common duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia); Greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros); Impala (Aepyceros melampus); Warthog (Phacochoerus africanus).

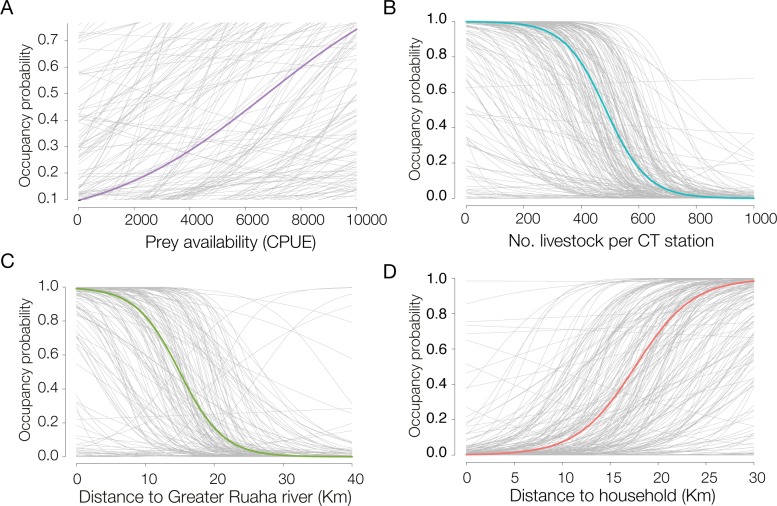

We found a significantly strong negative relationship between the probability of leopard site use and habitats that were closer to households. Similarly, we observed a negative, albeit highly variable and non-significant, influence of increased livestock presence on leopard site use. Additionally, we found no evidence for a relationship between prey availability, distance to the Great Ruaha River, and the probability of leopard site use (Table 3; Fig 4). The relatively high Bayesian inclusion parameter values (wc−Table 3) for both proximity to households and livestock presence, in comparison to prey availability, suggest that leopard site use was primarily influenced by lower levels of anthropogenic pressure than prey availability during the survey. Finally, we found a lack of effect of trail type on detection probability (Table 3).

Table 3. Posterior means, standard deviations (S.D.), 95% credible intervals (C.I.), and Bayesian inclusion parameters (wc) of leopard site use models fit to camera-trap data from the Ruaha landscape, southern Tanzania, during the dry seasons of 2014–2015.

| Covariates | Parameter | Mean | S.D. | 95% (C.I.) | wc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Livestock presence | α1 | -5.5 | 2.97 | -9.82, 0.09 | 0.47 |

| Distance to Great Ruaha River | α2 | -1.94 | 1.66 | -5.66, 1.27 | 0.33 |

| Distance to households | α3 | 2.96 | 1.48 | 0.46, 6.31 | 0.73 |

| Prey availability (CPUE) | α4 | 0.62 | 0.58 | -0.23, 2.04 | 0.1 |

| Intercept | β0 | -1.59 | 0.09 | -1.77, -1.41 | NA |

| Trail type N | βk2 | -0.21 | 0.45 | -1.05, 0.61 | 0.01 |

| Trail type RD | βk3 | -0.55 | 0.39 | -1.4, 0.15 | 0.01 |

| Estimated number of sites used | Ψ*- | 51.83 | 4.02 | 45, 60 | NA |

* Denotes estimated number of sites used out of all surveyed sites.

Fig 4. Predicted association of the covariates to the probability of site use of leopards (Panthera pardus).

The solid line represents the posterior mean, and the light grey lines represent the estimated uncertainty based on a random posterior sample of 150–200 iterations. Occupancy probability = site use.

4. Discussion

Our findings suggest that human-related activities such as increased livestock presence and proximity to human households exerted stronger influence than prey availability on leopard site use, and were the major limiting factors of leopard distribution across the gradient of human pressure, especially in the village lands outside Ruaha National Park. Leopards have been shown to adapt to heavily disturbed anthropogenic environments, occurring in areas with high human densities and of low wild prey density [19, 62, 63]. Importantly, our results suggest that such adaptations to human-pressure and threats may be context-specific [64]. It is crucial to highlight that the limited leopard site use observed outside the national park should not be interpreted as a result of the covariates considered in this study in isolation, but also as a consequence of the underlying high persecution and human induced mortality of large carnivores in the study site [28, 65]. The combination of these factors is likely limiting leopard occurrence outside the protected area in the Ruaha landscape.

Determinants of leopard site use

The lack of leopard detections in the village lands suggests low population densities for the species in the unprotected areas surrounding Ruaha National Park. This area has undergone rapid conversion of habitats due to intense human and livestock encroachment [66, 67], intense conflict and high human-induced carnivore killing [28, 65], with all these factors likely contributing towards creating a hard edge for leopard populations in these non-protected areas. These results are similar to those presented by Henschel et al. [68] and Ramesh et al. [69], that found leopard use of habitat and abundance to be negatively influenced by areas with high human activity or increased bushmeat poaching. The negative influence of livestock presence on leopard site use could suggest a potential risk-avoidance strategy targeted at areas of intense human exposure. Large carnivores have been found to change and adjust spatiotemporal behaviour and home range in areas of intense herding activities to minimise exposure to human herders and livestock [70, 71]. Alternatively, intense livestock herding could be associated with overgrazing and potential displacement of wild prey across the village lands, although our analyses showed little support for this hypothesis. It is noteworthy that the lack of leopard detections in village lands should not be understood as the absence of the species in these areas. Leopards undoubtedly use these village lands, as indicated by reported livestock depredations, and the corresponding number of leopard killings in this area [28]. We acknowledge that the precise mechanistic connections between low-levels of leopard detections in the village lands and the variety of sources of anthropogenic pressure are elusive. In addition, our sampling strategy might have influenced our ability to capture habitat heterogeneity for particular covariates (e.g. livestock presence and distance to households), which could be limiting detection probability, and the models to precisely estimate the effect of such covariates on leopard habitat use. The limitations of camera-traps to only survey relatively small areas, associated with the likely low leopard densities and detection probability in village lands, means that broader survey across the whole landscape, and the use of complementary methods such as spoor tracks could render a more precise estimate of the variables influencing leopard site use in these areas of human occupation. Furthermore, due to lack of available data, we did not account for leopard movement pattern and home-range variation across the landscape and between seasons, which may have contributed to limit our site use estimates. These factors have been recently shown to substantially influence on species detection and site occupancy estimates from camera-trapping studies [72, 73]. Thus, further work based on camera-trapping should, whenever possible, incorporate movement data to improve site use and occupancy estimates. Despite these limitations, our results are the first to investigate the environmental determinants of leopard site use across the gradient of anthropogenic pressure in the Ruaha landscape, and provide much needed data to help furthering our understanding of the effects of human activities on limiting leopard spatial distribution across one of the most important large carnivore strongholds in East Africa.

The observed weak association between leopard site use and primary prey availability (Table 3; Fig 4) provided an interesting insight into leopard ecology in this landscape. Prey availability is a known determinant of site use, spatial distribution, and population density of leopards [15, 38, 74] and other carnivores [22, 75, 76]. In fact, recent studies have shown that areas of increased leopard population density were linked to high abundance of medium-sized wild prey [15, 69]. One explanation of the observed weak relationship is that leopards could be relying on smaller prey species than those considered in this study, especially outside Ruaha National Park, as a potential response to larger prey scarcity. Leopards are known to shift and rely on small-sized prey species (<20 kg) in areas of increased bushmeat hunting and intense competition with humans for limited food resources [42, 68, 77], similar to those of the village lands around the national park. The low prey detection across village lands, where they are exposed to intense bushmeat poaching [78], could help to corroborate such hypothesis (Figs 2 and 3). Even though we found weak association between leopard site use and prey availability, it is nonetheless important to highlight that prey depletion could still pose a serious threat to leopards locally. Prey depletion is one of the main limiting factors to leopard occurrence and population density across their extant range, and potentially more detrimental to their survival than direct human-induced killings [15, 19, 69].

Implications for leopard conservation

Our results highlight the importance of protected areas on the conservation of wide-ranging large carnivores such as the leopard. Large protected areas such as Ruaha National Park are fundamental in protecting important habitats for leopards and other large carnivores [79, 80] against the increasing human pressure observed in village lands surrounding protected areas across Africa [8, 9, 66]. Our findings suggest that intense human activities, likely coupled with underlying high levels of human-induced carnivore mortality due to conflict [28, 36, 81], represent key-limiting factors to leopard spatial distribution in the human-dominated non-protected areas around Ruaha National Park. Similar results have been found elsewhere in Africa, where the spatial distribution and population density of leopards [15], as well as of other large carnivores such as lions [82] and other smaller carnivores [14, 83] have been limited by increased human and livestock encroachment, pastoralism, conflict and human-mediated mortality in anthropogenic landscapes surrounding protected areas. If leopards are to be successfully conserved in such areas of human occupation, it is vital to address the threats imposed by people and livestock immediately adjacent to protected areas.

In the context of this study, one much-needed strategy is the mitigation of carnivore-related conflict with people [28, 65, 81]. Increasing people’s awareness and access to effective actions to reduce the perceived hazard originating from carnivore presence could help to increase tolerance and improve attitudes towards leopards and other large carnivores locally [84]. For example, systematic widespread improvement of husbandry practices using predator-proof bomas [81, 85], and prevention of human-carnivore conflict could lead to a substantial reduction in leopard and other large carnivore mortality, and contribute to conservation of these species in the village lands [65]. Additionally, developing strategies to reduce the associated costs of large carnivores’ presence while increasing the tangible benefits of having these species in the village lands could help to promote their conservation [65, 86, 87]. For instance, the provisions of veterinary medicines, health care, and education associated with large carnivore presence as part of a community-based conservation approach in some of the villages around Ruaha National Park resulted in 80% decline of large carnivore killing, although those initiatives currently operate across less than half of the village land [65].

On a landscape level, concerted efforts to develop integrated management strategies and adaptive livestock and wildlife foraging systems could help limit the impact of livestock on rangeland habitats and wildlife [88]. Guaranteed access to optimum foraging sites by livestock, and the implementation of planned grazing strategies–which consists of establishing several grazing paddocks that enable livestock rotation based on forage growth rate—across rangelands could help minimising competition with wildlife, prey depletion, habitat degradation due to overgrazing, and ultimately promote wildlife conservation [88, 89]. However, these strategies can be difficult to implement in areas where livestock owners can be highly nomadic and transient, as is the case in the vicinity of Ruaha National Park. Finally, we emphasize that strategies aimed at conserving leopards and other large carnivores within human-dominated lands should be implemented in collaboration with local communities, given that these local communities will bear the costs of co-existing with these species, and ultimately be responsible for deciding upon their conservation [90].

Supporting information

A. Distance to the Great Ruaha River; B. Distance to households. Primary prey availability (CPUE), livestock presence and trail type not represented here.

(TIF)

Spline correlograms from a generalized linear model (A) and a generalized linear mixed model that included a random intercept at the CT level (B) showing a reduction in spatial autocorrelation. Distance between paired sample locations in kilometres (Km).

(TIF)

Dist.: distance.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

L.A. thanks TAWIRI/TANAPA, RCP staff, Christos Astaras, Paul Johnson, and Nuno Faria.

Data Availability

The leopard occurrence data used for the model can be found freely available at https://github.com/labade/GitHub/tree/master/leop_occu_data.

Funding Statement

L.A. was supported by a CNPq-Brasil scholarship (215981/2013-8), and grants by the Rufford Foundation (Rufford Small Grants), Cleveland Metroparks Zoo/ Cleveland Zoological Society, IdeaWild, Lady Margaret Hall, WildCRU, and Ruaha Carnivore Project. J.C. was supported by the UK Natural Environment Research Council, R.J.M. was supported by an National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ripple WJ, Estes JA, Beschta RL, Wilmers CC, Ritchie EG, Hebblewhite M, et al. Status and ecological effects of the world’s largest carnivores. Science. 2014;343(6167). 10.1126/science.1241484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen BL, Allen LR, Andrén H, Ballard G, Boitani L, Engeman RM, et al. Can we save large carnivores without losing large carnivore science? Food Webs. 2017;12:64–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodroffe R, Redpath SM. When the hunter becomes the hunted. Science. 2015;348(6241):1312–4. 10.1126/science.aaa8465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Minin E, Leader-Williams N, Bradshaw CJA. Banning trophy hunting will exacerbate biodiversity loss. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2016;31(2):99–102. 10.1016/j.tree.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creel S, M'Soka J, Dröge E, Rosenblatt E, Becker MS, Matandiko W, et al. Assessing the sustainability of African lion trophy hunting, with recommendations for policy. Ecological Applications. 2016;26(7):2347–57. 10.1002/eap.1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macdonald DW. Animal behaviour and its role in carnivore conservation: examples of seven deadly threats. Animal Behaviour. 2016;120:197–209. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2016.06.013 PubMed PMID: WOS:000385375900022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ripple WJ, Abernethy K, Betts MG, Chapron G, Dirzo R, Galetti M, et al. Bushmeat hunting and extinction risk to the world's mammals. R Soc Open Sci. 2016;3(10):160498 10.1098/rsos.160498 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5098989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wittemyer G, Elsen P, Bean WT, Burton ACO, Brashares JS. Accelerated human population growth at protected area edges. Science. 2008;321(5885):123–6. 10.1126/science.1158900 PubMed PMID: WOS:000257320800052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newmark WD. Isolation of African protected areas. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2008;6(6):321–8. 10.1890/070003 PubMed PMID: WOS:000258249200018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodroffe R, Ginsberg JR. Edge Effects and the Extinction of Populations Inside Protected Areas. Science. 1998;280(5372):2126–8. 10.1126/science.280.5372.2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loveridge AJ, Hemson G, Davidson Z, Macdonald D. African lions on the edge: reserve boundaries as "attractive sinks" In: Macdonald DW, Loveridge AJ, editors. Biology and conservation of Wild Felids. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 283–304. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loveridge AJ, Valeix M, Elliot NB, Macdonald DW. The landscape of anthropogenic mortality: how African lions respond to spatial variation in risk. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2016;54(3):815–25. 10.1111/1365-2664.12794 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treves A, Karanth KU. Human-carnivore conflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conservation Biology. 2003;17(6):1491–9. 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2003.00059.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burton AC, Sam MK, Balangtaa C, Brashares JS. Hierarchical multi-species modeling of carnivore responses to hunting, habitat and prey in a West African protected area. Plos One. 2012;7(5). doi: ARTN e38007 10.1371/journal.pone.0038007 PubMed PMID: WOS:000305353400068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenblatt E, Creel S, Becker MS, Merkle J, Mwape H, Schuette P, et al. Effects of a protection gradient on carnivore density and survival: an example with leopards in the Luangwa valley, Zambia. Ecology and Evolution. 2016;6(11):3772–85. 10.1002/ece3.2155 PubMed PMID: WOS:000377043200026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swanepoel LH, Lindsey P, Somers MJ, Van Hoven W, Dalerum F. Extent and fragmentation of suitable leopard habitat in S outh A frica. Animal Conservation. 2013;16(1):41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitman RT, Swanepoel LH, Hunter L, Slotow R, Balme GA. The importance of refugia, ecological traps and scale for large carnivore management. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2015;24(8):1975–87. 10.1007/s10531-015-0921-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Meer E, Fritz H, Blinston P, Rasmussen GSA. Ecological trap in the buffer zone of a protected area: effects of indirect anthropogenic mortality on the African wild dog Lycaon pictus. Oryx. 2014;48(2):285–93. 10.1017/S0030605312001366 PubMed PMID: WOS:000337969700020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobson AP, Gerngross P, Lemeris JR, Schoonover RF, Anco C, Breitenmoser-Wursten C, et al. Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range. Peerj. 2016;4. doi: ARTN e1974 10.7717/peerj.1974 PubMed PMID: WOS:000376488700001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Athreya V, Odden M, Linnell JDC, Krishnaswamy J, Karanth KU. A cat among the dogs: leopard Panthera pardus diet in a human-dominated landscape in western Maharashtra, India. Oryx. 2016;50(1):156–62. 10.1017/S0030605314000106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braczkowski AR, O'Bryan CJ, Stringer MJ, Watson JE, Possingham HP, Beyer HL. Leopards provide public health benefits in Mumbai, India. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2018;16(3):176–82. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf C, Ripple WJ. Prey depletion as a threat to the world's large carnivores. Roy Soc Open Sci. 2016;3(8). doi: ARTN 160252 10.1098/rsos.160252 PubMed PMID: WOS:000384411000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein AB, Athreya V, Gerngross P, Balme G, Henschel P, Karanth U, et al. Panthera pardus (errata version published in 2016). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.TAWIRI. Proceedings of the first Tanzania lion and leopard conservation action plan workshop. Arusha, Tanzania: Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.TAWIRI. Tanzania carnivore conservation action plan. Arusha: 2009.

- 26.Green KE, Adams WM. Green grabbing and the dynamics of local-level engagement with neoliberalization in Tanzania's wildlife management areas. The Journal of Peasant Studies. 2015;42(1):97–117. 10.1080/03066150.2014.967686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NBS. Iringa region social-economic profile. Dar Es Salaam: Ministry of Finance, National Bureau of Statistics, Iringa Regional Secretariat, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickman AJ, Hazzah L, Carbone C, Durant SM. Carnivores, culture and ‘contagious conflict’: Multiple factors influence perceived problems with carnivores in Tanzania’s Ruaha landscape. Biological Conservation. 2014;178(0):19–27. 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh MT. The Development of Community Wildlife Management in Tanzania: Lessons from the Ruaha Ecosystem. Mweka,Tanzania: African Wildlife Management in the New Millennium; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sosovele H, Ngwale JJ. Socio-economic root causes of the loss of biodiversity in the Ruaha catchment area. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cusack JJ, Dickman AJ, Rowcliffe JM, Carbone C, Macdonald DW, Coulson T. Random versus game trail-based camera trap placement strategy for monitoring terrestrial mammal communities. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5): e0126373 10.1371/journal.pone.0126373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wearn OR, Rowcliffe JM, Carbone C, Bernard H, Ewers RM. Assessing the status of wild felids in a highly-disturbed commercial forest reserve in Borneo and the implications for camera trap survey design. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e77598 10.1371/journal.pone.0077598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacKenzie DI, Nichols JD, Lachman GB, Droege S, Andrew Royle J, Langtimm CA. Estimating site occupancy rates when detection probabilities are less than one. Ecology. 2002;83:2248–55. [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacKenzie DI, Nichols JD. Occupancy as a surrogate for abundance estimation. Animal biodiversity and conservation. 2004;27(1):461–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacKenzie DI, Nichols JD, Royle JA, Pollock KH, Bailey LL, Hines JE. Occupancy estimation and modeling Inferring patterns and dynamics of species occurrence: Elsevier Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abade L, Macdonald DW, Dickman AJ. Using landscape and bioclimatic features to predict the distribution of lions, leopards and spotted hyaenas in Tanzania's Ruaha landscape. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e96261 10.1371/journal.pone.0096261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey TN. The African leopard: ecology and behavior of a solitary felid. Caldwell, New Jersey: Blackburn Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balme G, Hunter L, Slotow R. Feeding habitat selection by hunting leopards Panthera pardus in a woodland savanna: prey catchability versus abundance. Animal Behaviour. 2007;74(3):589–98. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gavashelishvili A, Lukarevskiy V. Modelling the habitat requirements of leopard Panthera pardus in west and central Asia. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2008;45(2):579–88. 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01432.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pitman RT, Swanepoel LH, Ramsay PM. Predictive modelling of leopard predation using contextual Global Positioning System cluster analysis. Journal of Zoology. 2012;288(3):222–30. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2012.00945.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.QGIS.

- 42.Hayward MW, Henschel P, O'Brien J, Hofmeyr M, Balme G, Kerley GIH. Prey preferences of the leopard (Panthera pardus). Journal of Zoology. 2006;270(2):298–313. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00139.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tacutu R, Craig T, Budovsky A, Wuttke D, Lehmann G, Taranukha D, et al. Human Ageing Genomic Resources: integrated databases and tools for the biology and genetics of ageing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D1027–33. 10.1093/nar/gks1155 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3531213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quinn TJ, Deriso RB. Quantitative fish dynamics: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hilborn R, Walters CJ. Quantitative fisheries stock assessment: choice, dynamics and uncertainty: Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seber GA. A review of estimating animal abundance II. International Statistical Review/Revue Internationale de Statistique. 1992:129–66. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gese EM. Monitoring of terrestrial carnivore populations. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burn RW, Underwood FM, Blanc J. Global trends and factors associated with the illegal killing of elephants: a hierarchical Bayesian analysis of carcass encounter data. PLoS one. 2011;6(9):e24165 10.1371/journal.pone.0024165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keane A, Jones JP, Milner‐Gulland E. Encounter data in resource management and ecology: pitfalls and possibilities. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2011;48(5):1164–73. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burton AC, Sam MK, Balangtaa C, Brashares JS. Hierarchical multi-species modeling of carnivore responses to hunting, habitat and prey in a West African protected area. PloS one. 2012;7(5):e38007 10.1371/journal.pone.0038007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Long RA, Donovan TM, MacKay P, Zielinski WJ, Buzas JS. Predicting carnivore occurrence with noninvasive surveys and occupancy modeling. Landscape Ecol. 2011;26(3):327–40. 10.1007/s10980-010-9547-1 PubMed PMID: ISI:000288808100003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Elphick CS. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2010;1(1):3–14. 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00001.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tyre AJ, Tenhumberg B, Field SA, Niejalke D, Parris K, Possingham HP. Improving precision and reducing bias in biological surveys: Estimating false-negative error rates. Ecological Applications. 2003;13(6):1790–801. 10.1890/02-5078 PubMed PMID: WOS:000187616400022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rhodes JR, McAlpine CA, Zuur AF, Smith GM, Ieno EN. GLMM applied on the spatial distribution of koalas in a fragmented landscape In: Zuur AF, editor. Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. New York: Springer; 2009. p. 469–92. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moll RJ, Kilshaw K, Montgomery RA, Abade L, Campbell RD, Harrington LA, et al. Clarifying habitat niche width using broad-scale, hierarchical occupancy models: a case study with a recovering mesocarnivore. Journal of Zoology. 2016;300(3):177–85. 10.1111/jzo.12369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2.15.1 ed. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Plummer M. JAGS: a program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Distributed Statistical Computing; March 20–22; Vienna, Austria2003.

- 58.Su YS, Yajima M. R2jags: a package for running jags from R. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuo L, Mallick B. Variable selection for regression models. Sankhyā: The Indian Journal of Statistics. 1998;60(Series B):65–81. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Royle JA, Dorazio RM. Hierarchical modeling and inference in ecology: The analysis of data from populations, metapopulations and communities San Diego, California: Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gelman A, Hill J. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Gelman A, editor. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Athreya V, Odden M, Linnell JDC, Krishnaswamy J, Karanth U. Big cats in our backyards: persistence of large carnivores in a human dominated landscape in India. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e57872 10.1371/journal.pone.0057872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Athreya V, Srivathsa A, Puri M, Karanth KK, Kumar NS, Karanth KU. Spotted in the news: using media reports to examine leopard distribution, depredation, and management practices outside protected areas in Southern India. PLoS One. 2015;10(11). doi: ARTN e0142647 10.1371/journal.pone.0142647 PubMed PMID: WOS:000364430700149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alexander JS, Shi K, Tallents LA, Riordan P. On the high trail: examining determinants of site use by the Endangered snow leopard Panthera uncia in Qilianshan, China. Oryx. 2016;50(2):231–8. 10.1017/S0030605315001027 PubMed PMID: WOS:000372525900014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dickman AJ. Large carnivores and conflict in Tanzania's Ruaha landscape In: Redpath SM, Gutiérrez RJ, Wood KA, Evely A, Young JC, editors. Conflicts in Conservation: Navigating towards solutions: Cambridge University Press; 2015. p. 30–2. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lankford B, Tumbo S, Rajabu K. Water competition, variability and river basin governance: a critical analysis of the Great Ruaha River, Tanzania In: Molle F, wester P, editors. River basin trajectories: societies, environment and development. London, UK: CABI International; 2009. p. 171–95. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wenban-Smith H. Population growth, internal migration and urbanisation in Tanzania, 1967–2012: Phase 2 (Final Report). International Growth Centre, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Henschel P, Hunter LTB, Coad L, Abernethy KA, Mühlenberg M. Leopard prey choice in the Congo Basin rainforest suggests exploitative competition with human bushmeat hunters. Journal of Zoology. 2011;285(1):11–20. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00826.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ramesh T, Kalle R, Rosenlund H, Downs CT. Low leopard populations in protected areas of Maputaland: a consequence of poaching, habitat condition, abundance of prey, and a top predator. Ecology and Evolution. 2017;7(6):1964–73. 10.1002/ece3.2771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kolowski JM, Holekamp KE. Ecological and anthropogenic influences on space use by spotted hyaenas. Journal of Zoology. 2009;277(1):23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oriol-Cotterill A, Macdonald DW, Valeix M, Ekwanga S, Frank LG. Spatiotemporal patterns of lion space use in a human-dominated landscape. Animal Behaviour. 2015;101:27–39. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.11.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stewart FE, Fisher JT, Burton AC, Volpe JP. Species occurrence data reflect the magnitude of animal movements better than the proximity of animal space use. Ecosphere. 2018;9(2). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Neilson EW, Avgar T, Burton AC, Broadley K, Boutin S. Animal movement affects interpretation of occupancy models from camera‐trap surveys of unmarked animals. Ecosphere. 2018;9(1). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Balme GA, Batchelor A, Britz ND, Seymour G, Grover M, Hes L, et al. Reproductive success of female leopards Panthera pardus: the importance of top-down processes. Mammal Review. 2013;43(3):221–37. 10.1111/j.1365-2907.2012.00219.x PubMed PMID: ISI:000319982700006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hayward MW, O’Brien J, Kerley GIH. Carrying capacity of large African predators: Predictions and tests. Biological Conservation. 2007;139(1–2):219–29. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carbone C, Gittleman JL. A common rule for the scaling of carnivore density. Science. 2002;295(5563):2273–6. 10.1126/science.1067994 PubMed PMID: ISI:000174561700048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pitman RT, Mulvaney J, Ramsay PM, Jooste E, Swanepoel LH. Global Positioning System-located kills and faecal samples: a comparison of leopard dietary estimates. Journal of Zoology. 2014;292(1):18–24. 10.1111/jzo.12078 PubMed PMID: WOS:000328679000003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Knapp E, Peace N, Bechtel L. Poachers and poverty: assessing objective and subjective measures of poverty among illegal hunters outside Ruaha National Park, Tanzania. Conservation and Society. 2017;15(1):24–32. 10.4103/0972-4923.201393 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lindsey PA, Petracca LS, Funston PJ, Bauer H, Dickman A, Everatt K, et al. The performance of African protected areas for lions and their prey. Biological Conservation. 2017;209:137–49. 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.01.011 PubMed PMID: WOS:000404308600017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Di Minin E, Slotow R, Hunter LTB, Montesino Pouzols F, Toivonen T, Verburg PH, et al. Global priorities for national carnivore conservation under land use change. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:23814 10.1038/srep23814 PubMed PMID: PMC4817124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Abade L, Macdonald DW, Dickman AJ. Assessing the relative importance of landscape and husbandry factors in determining large carnivore depredation risk in Tanzania’s Ruaha landscape. Biological Conservation. 2014;180(0):241–8. 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Everatt KT, Andresen L, Somers MJ. The influence of prey, pastoralism and poaching on the hierarchical use of habitat by an apex predator. African Journal of Wildlife Research. 2015;45(2):187–96. 10.3957/056.045.0187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rich LN, Miller DAW, Robinson HS, McNutt JW, Kelly MJ. Using camera trapping and hierarchical occupancy modelling to evaluate the spatial ecology of an African mammal community. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2016;53(4):1225–35. 10.1111/1365-2664.12650 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bruskotter JT, Wilson RS. Determining where the wild things will be: using psychological theory to find tolerance for large carnivores. Conservation Letters. 2014;7(3):158–65. 10.1111/conl.12072 PubMed PMID: WOS:000337590000003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lichtenfeld LL, Trout C, Kisimir EL. Evidence-based conservation: predator-proof bomas protect livestock and lions. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2015;24(3):483–91. 10.1007/s10531-014-0828-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hemson G, Maclennan S, Mills G, Johnson P, Macdonald D. Community, lions, livestock and money: A spatial and social analysis of attitudes to wildlife and the conservation value of tourism in a human-carnivore conflict in Botswana. Biological Conservation. 2009;142(11):2718–25. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Blackburn S, Hopcraft JGC, Ogutu JO, Matthiopoulos J, Frank L. Human–wildlife conflict, benefit sharing and the survival of lions in pastoralist community-based conservancies. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2016;53(4):1195–205. 10.1111/1365-2664.12632 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fynn RWS, Augustine DJ, Peel MJS, de Garine-Wichatitsky M. Strategic management of livestock to improve biodiversity conservation in African savannahs: a conceptual basis for wildlife–livestock coexistence. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2016;53(2):388–97. 10.1111/1365-2664.12591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Odadi WO, Fargione J, Rubenstein DI. Vegetation, wildlife and livestock responses to planned grazing management in an Arican pastoral landscape. Land Degradation & Development. 2017;28(7):2030–8. 10.1002/ldr.2725 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dolrenry S, Hazzah L, Frank G. Conservation and monitoring of a persecuted African lion population by Maasai warriors. Conservation Biology. 2016;30(3):467–75. 10.1111/cobi.12703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Distance to the Great Ruaha River; B. Distance to households. Primary prey availability (CPUE), livestock presence and trail type not represented here.

(TIF)

Spline correlograms from a generalized linear model (A) and a generalized linear mixed model that included a random intercept at the CT level (B) showing a reduction in spatial autocorrelation. Distance between paired sample locations in kilometres (Km).

(TIF)

Dist.: distance.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

The leopard occurrence data used for the model can be found freely available at https://github.com/labade/GitHub/tree/master/leop_occu_data.