Abstract

Who will revere the Black woman? Who will keep our neighborhoods safe for Black innocent womanhood? Black womanhood is outraged and humiliated. Black womanhood cries for dignity and restitution and salvation. Black womanhood wants and needs protection, and keeping, and holding. Who will assuage her indignation? Who will keep her precious and pure? Who will glorify and proclaim her beautiful image? To whom will she cry rape? Abbey Lincoln, 1970

Though written almost fifty years ago, Lincoln’s essay still resonates today.1 This eloquent prose still eerily reflects the struggles that many Black women must navigate, especially those residing in the neighborhoods Jim Crow built. In urban Jim Crow, violence is the mortar that lies between the brick and stone constructing this space. Violence is a daily reality that seems to exist just about everywhere. For a woman living within the confines of Jim Crow, violence resides in and outside of home: the bed where she sleeps, the space in which she strolls, the environment where she works, and even the places where she goes for recreation. Jim Crow has left a legacy of regulating property through racial zoning policy, then restrictive covenants, and later, through the practice of redlining and racial steering policy (1877–1960s), creating what I call Jim Crow geographies. In the post- 1970s or the “new” Jim Crow era, these spaces continued to be created by policy, as noted by Richard Rothstein, in addition to the custom of white flight.2 Today many of Cincinnati city’s forty-eight neighborhoods still reflect the zoning policies that created homogeneous communities on the basis of race and social class.

This study contextualizes Jim Crow, as a definitive form of structural violence, as the architect of spatial violence, and as the predicate of direct violence. Structural violence refers to social arrangements, actions, and policies that bring harm to social groups or individuals by unevenly distributing or restricting access to the basic goods, services, and resources needed to sustain human life. Reciprocal to structural violence is direct violence, which occurs between individuals through direct contact and results in either physical or psychological harm. Significantly, the relationship between structural and interpersonal violence is mediated by spatial violence, which refers to the aggregate or totality of direct and indirect violence occurring within community boundaries or physical geographical space, regardless of whether a given individual has direct knowledge of this violence.

These forms of violence precipitated by Jim Crow have left a legacy of psychological trauma and damage. From slavery to Jim Crow, the Black female body has been brutally and routinely compromised in the absence of legal protection.3 Controlling tropes of hypersexuality continue to cultivate the perception of Black women as being unvictimizable.4 Such historical controlling images silence Black women, who are thus less likely to disclose their having been assaulted compared to other US women.5 The sexual trauma inflicted onto Black women’s bodies and the imposed silence and stigma continue to shape the lives of Black women; particularly those still residing in the confines of Jim Crow geographies.

Concurrently, these forms of violence and trauma cultivate disparate sexual health outcomes for Black women in Cincinnati. This qualitative study explores the ways Black women navigate daily life within the confines of Cincinnati’s urban Jim Crow neighborhoods and the impact of this confinement on their sexual health.

THE STRUCTURSAL VIOLENCE OF JIM CROW CINCINNATI

The city of Cincinnati has a long history of inflicting structural violence on its Black residents. Though the term “Jim Crow” can be traced back to 1830, the practice of Jim Crow began much earlier with the ratification of Black Codes in Ohio in 1804. And though Jim Crow is often singularly presented as a southern and rural phenomenon, truth be told, the strange career of Jim Crow originated in practice in the North.6 Ohio was among the first US territories to implement it.7 When Ohio adopted Black Codes in 1804 (two years after gaining statehood) in lieu of slavery, it opted to regulate Blacks’ subordination, mobility, and confinement through law in forms of ordinances, statutes, court decisions, and policies, in addition to ordinary customs.

The Ohio Black laws sought to control and impose confinement on free Blacks within public space. Life under the Black Codes was difficult; there were clear and definitive limits on people’s freedom. As Nikki Taylor notes, many Black Cincinnatians faced all sorts of social and economical obstacles: to public schools; they could not serve on juries; and those in-migrating to Ohio were made to register, pay a $500 fee, and obtain white sponsorship vouching for their good behavior.8 Free Black Cincinnatians labored in the lowest occupational sector as domestics for whites or as service field-hand workers.9 Given the proximity to Kentucky, a slave state, they lived under constant threat of being kidnapped by profit-driven slave catchers. In addition, during the antebellum era there were several episodes of white mob uprisings, which sought to instill fear and restrict the mobility and agency of Black Cincinnatians.

Nikki Taylor also notes that as a city, Cincinnati was “hypercongested,” meaning that people of various social classes were likely to reside on the same block.10 And although African Americans were clustered in specific areas along the Ohio River, namely neighborhoods like “Bucktown” and “Little Africa,” they did not dominate these areas and as such were not yet ghettoized. In the post-reconstruction era of 1877–1960s, Black laws gave way to what is now called Jim Crow. Though most Blacks lived with and around whites, and as such were not particularly segregated, it was in this period that residential segregation patterns began to emerge. These “embryonic ghettos,” as John Logan and colleagues called them, began to develop in Cincinnati.11 Residential segregation was just beginning to form, but it did not intensify until the great migrations of the 1900s.

THE MAKING OF URBAN JIM CROW

To be clear, US urban Black “ghettos” are the byproduct of Jim Crow policy, and Cincinnati Jim Crow neighborhoods are themselves a derivative of structural violence. As shown in table 1, twenty-first-century Cincinnati neighborhoods reflect the spatial legacy of Jim Crow, in that more than one third of these communities had an African American population that exceeded 50 percent of the total population in 2005–09.

Table 1.

Cincinnati (Majority) Black neighborhood characteristics

| Cincinnati “Black Neighborhoods” (communities that are more than 50% Black) | Percent Black 1960a | Percent Black 1970b | Percent Black 2005–09b | Jobless rate 2005–09b | Median household income 2005–09b | Percent families living below poverty 2005–09b | Neighborhood violent crime by type (Rate per 1,000), 2009c | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Jim Crow neighborhoods |

Aggravated assault (n) | Rate per lk | Homicide (n) | Rate per lk | Rape(n) | Rate per lk | Robbery (n) | Rate per lk | ||||||

| *e.g., predominantly Black POST Civil Rights Act 1964 and Fair Housing Act 1968 | ||||||||||||||

| Bond Hill | 0.0% | 26.2% | 92.7% | 40.0% | 32,447 | 17.8% | 30 | 3.10 | 1 | 0.10 | 4 | 0.413 | 52 | 5.37 |

| College Hill | 2.0% | 11.2% | 54.2% | 34.0% | $56,540 | 17.3% | 26 | 1.70 | — | 0.00 | 4 | 0.262 | 64 | 4.19 |

| Fay Apartments | 1.0% | 33%a | 92.3% | 71.0% | $9,808 | 71.5% | 21 | 8.56 | 2 | 0.82 | 6 | 2.446 | 18 | 7.34 |

| Kennedy Heights | 17.0% | 58.1% | 70.8% | 37.0% | $49,656 | 11.1% | 14 | 2.64 | — | 0.00 | 2 | 0.378 | 15 | 2.83 |

| Madisonville | 21.0% | 49.3% | 55.8% | 28.0% | $54,054 | 11.9% | 18 | 1.66 | 1 | 0.09 | 6 | 0.554 | 39 | 3.60 |

| Mt. Airy | 0.0% | 20.0% | 54.1% | 34.0% | $34,949 | 21.3% | 20 | 2.06 | 2 | 0.21 | 6 | 0.618 | 42 | 4.33 |

| Mt. Auburn | 10.0% | 73.9% | 52.5% | 42.0% | $28,400 | 34.8% | 24 | 3.68 | 2 | 0.31 | 1 | 0.153 | 43 | 6.60 |

| N. Fair mount- English Woods |

23.0% | 44.3% | 65.7% | 48.0% | $32,353 | 24.7% | 17 | 3.77 | 1 | 0.22 | 5 | 1.109 | 17 | 3.77 |

| Over-the-Rhine | 13.0% | 41.4% | 74.8% | 38.0% | $10,522 | 61.7% | 122 | 15.97 | 5 | 0.65 | 18 | 2.357 | 226 | 29.59 |

| Roselawn | 7.0% | 6.8% | 65.7% | 67.0% | $41,765 | 23.2% | 17 | 2.50 | 1 | 0.15 | 7 | 1.029 | 65 | 9.55 |

| S. Fairmount | 1.0% | 26.0% | 49.7% | 45.0% | $31,538 | 38.9% | 25 | 7.69 | — | 0.00 | 3 | 0.923 | 45 | 13.84 |

| Winston Place | 0.0% | 1.0% | 59.4% | 36.0% | $44,345 | 28.7% | 35 | 6.73 | 2 | 0.38 | 8 | 1.537 | 34 | 6.53 |

| Winston Hills | 4.0% | 75.2% | 82.7% | 61.0% | $10,167 | 66.4% | 5 | 2.14 | — | 0.00 | 1 | 0.428 | 23 | 9.84 |

| Old Jim Crow neighborhoods |

Aggravated assault (n) | Rate per lk | Homicide (n) | Rate per lk | Rape (n) | Rate per lk | Robbery (n) | Rate per lk | ||||||

| *e.g., predominantly Black PRE Civil Rights Act 1964 and Fair Housing Act 1968 | ||||||||||||||

| Avondale | 69.0% | 91.2% | 87.2% | 44.0% | $25,854 | 37.5% | 86 | 5.28 | 6 | 0.637 | 13 | 0.80 | 145 | 8.90 |

| Evanston | 66.0% | 74.1% | 81.4% | 46.0% | $30,764 | 21.2% | 37 | 20.50 | 4 | 2.22 | 9 | 4.99 | 76 | 42.11 |

| S. Cumminsville | 49.0% | 97.7% | 90.0% | 57.0% | $15,465 | 56.9% | 15 | 3.83 | 2 | 0.51 | — | 0.00 | 37 | 9.45 |

| Walnut Hills | 56.0% | 81.9% | 77.2% | 47.0% | $28,901 | 34.5% | 77 | 9.88 | 3 | 0.39 | 7 | 0.90 | 120 | 15.40 |

| West End | 94.0% | 97.1% | 80.6% | 44.0% | $16,606 | 48.8% | 58 | 7.15 | 4 | 0.49 | 6 | 0.74 | 93 | 11.46 |

| Total crime by type for Jim Crow neighborhoods |

647 | 5.08 | 36 | 0.28 | 106 | 0.83 | 1154 | 9.06 | ||||||

| Total crime by type for Cincinnati city | 1044 | 3.16 | 53 | 0.16 | 247 | 0.75 | 2271 | 6.88 | ||||||

| Percent of violent crime for Jim Crow neighborhood | 62% | 68% | 43% | 51% | ||||||||||

| Crime ratio of Maj ority Black Jim Crow neighborhoods to total Cincinnati city violent crime | 1.51 | 1 66 | 1.05 | 1.24 | ||||||||||

Majority Black Jim Crow neighborhoods population size is 41% of total population (n = 339,866) of Cincinnati City in 2005–09.

Note: Westwood, Cincinnati city’s largest neighborhood, is not presented here. Since the 2010 census, due to changes in Statistical Neighborhood Approximation (SNA), Westwood was divided into “east” (tracts 88 and 100) and “west.” Westwood-East is predominantly white and working class, though median income level is increasing due to gentrihcation. Westwood-West is predominantly Black, very low income, and has the highest violent crime rate in the city, leading in rapes (rank 1), robbery (rank 2), and aggressive assault (rank 4).

Source: Charles E Casey-Leininger, Hamilton County Stable Integrated Communities (Cincinnati: Cincinnatus Association, 2007), 1–61.

Source: Michael Maloney and Christopher Auffrey, The Social Areas of Cincinnati An Analysis of Social Needs: Patterns for Five Census Decades (School of Planning, University of Cincinnati, United Way, University of Cincinnati Community Research Collaborative, 2013): 1–213.

Source: Dan Wells, “Cincinnati’s Most Dangerous Neighborhoods,” Foxl9NOW-WIX, Februar)7 23, 2010, p. 1, http://www.foxl9.com/story/12026978/cincinnatis-most-dangerous-neighborhoods.

The Jim Crow geography of Blacks in Cincinnati follows three distinct time periods. The first Cincinnati ghetto emerged in the nineteenth century during the industrial expansion in the 1880s.12 It peaked in the 1920s through the 1940s, as a result of the steady flow of in-migrating Blacks and of out-migrating whites moving to newly established residential areas outside the city core.13

The second ghetto developed between 1940 and 1960.14 Th is process was the result of the superhighway construction projects and realtor schemes, such as blockbusting, redlining, and the slum clearance of the lower basin area.15 Between 1870 and 1940 the Black population increased 74% in this area of the city, and by 1940, 67% of Cincinnati Blacks lived in this area, formerly known as Queensgate and the West End.16 Blacks already had too few housing choices, and as the lower basin area of Queensgate was cleared out, housing congestion amplified. With new support for integrated neighborhoods among housing reformers in the 1950s, Blacks began to settle in large numbers in Walnut Hills and Avondale.17 Avondale still reflects this history, with more than 80% of its current population being Black.

The third ghettoization of Blacks occurred during what Michelle Alexander identifies as the New Jim Crow era, which is 1970 to the present.18 These neighborhoods, once labeled “integrated,” are now predominantly Black, as a result of persistent white flight and the steady influx of Blacks. Between 1970 and 2000 these neighborhoods became increasingly Black. Bond Hill increased from 26% to 93%, Fay Apartments 33% to 95%, and Roselawn 7% to 77%.19

Finally, there are neighborhoods like Corryville, West End, and Over-the-Rhine, where the Black population percentage shows strong signs of retraction. In Corryville the Black percentage decreased from 50% to 36% between 2000 and 2010. The displacement of African Americans in Corryville has been due to aggressive urban renewal efforts, which resulted in the construction of upscale housing and new restaurants and shops aimed at university professionals and students who work, and now reside, in this area.20

WHY DOSE JIM CROM SPACE MATTER?

Jim Crow’s most prominent legacy is residential segregation and its residual effects, which include disadvantaged housing conditions, poor schools, unsafe streets, limited access to jobs, stifled housing equity, and concentrated poverty.21 Effects also include a coercive sexual environment (though this is not unique to Jim Crow geographies).22 The cumulative impact of these conditions (which are also called social determinants of health) is pronounced community-level health disparities.23 As of 2016 many Black Cincinnatians still reside in what Massey and Denton characterize as “hyper-segregated” communities.24 The Cincinnati Primary Statistical Metropolitan Area ranks eighth in the nation in housing segregation between Blacks and Whites, with an index of dissimilarity score of .69.25 This means that 69% of Black Cincinnatians would need to relocate to a different census tract to create a racially heterogeneous distribution.

The longstanding problem of segregated Black neighborhoods is that they are acutely burdened by high rates of male unemployment, poverty, crime, and violence. Such circumstances can have catastrophic consequences for women, children, and family formation.

Concentrated disadvantage often translates to concentrated violence and crime, thus creating a social and physical environment fraught with uncertainty and all sorts of unacknowledged and untreated trauma. Cincinnati city neighborhoods far exceed all others in the county when it comes to violent crimes, such as rape, burglary, aggravated assault, and robbery. For example, according to a local news outlet, Westwood led the city in crimes of rape and burglary, while Over-the-Rhine had the most aggravated assaults and robberies, and Avondale had three of the deadliest blocks in the city in terms of homicides in 2009.26 As shown in table 1, Cincinnati Jim Crow neighborhoods account for a much higher ratio of violent crime. Compared to the rest of the city, total incidents of aggravated assault, homicide, rape, and robbery are 61%, 76%, 11%, and 32% (respectively) higher in these neighborhoods than in others.

Community violence, defined as “aggression that occurs outside the home among non-family members; [though] it may, and often does, involve known others and even family members as victims or perpetrators,” is particularly threatening to women and girls.27 Esther Jenkins and her colleagues’ work shows that a substantial number of Black women have witnessed violence: 30% have seen a murder, stabbing, or shooting. And many are victims of violence, such as homicide.28 In fact, in 2014 homicide was the second leading cause of death for Black women ages 15–24. According to the Women of Color Network, nearly one Black women in three is victimized by intimate partner violence in her lifetime (rape, physical assault, or stalking), a rate that is 35% higher than for white women and 2.5 times the rate of other US women. In addition, Black women are more likely to be a victim of intimate partner homicide compared to White women.29

Frequent experience with community violence leads to self-isolation. It also impedes collective efficacy, cultivates community silence, and normalizes violence.30 The normalization of violence then creates the expectation of violence, which then reduces the shock of an assault and decreases individual efficacy. These factors, in addition to levels of racism, perhaps explain why Black women are less likely to report their abusers or seek help.31 According to the Women of Color Network report, the threat of discrimination, combined with racial stigma and the vulnerability of Black men to police brutality, leads African American women often to be reluctant to report abuse and assault.32

As Susan Popkin and colleagues note, young girls and women in communities with concentrated disadvantage, high levels of segregation, and low collective efficacy are additionally challenged by a coercive sexual environment, whereby street and sexual harassment and threat of sexual exploitation and violence is unsparing and usual. Pathways between community violence and sexual risk are emerging.33 The work of Dexter Voisin and colleagues on community violence exposures among African American adolescents, for example, shows that higher levels of exposure to community violence are associated with sexual risk behaviors, such as having sex without condoms, drug use during sex, more sexual partners for men, and more encounters with unprotected sex with non-steady partners for women.34 In addition, individuals who report being victimized by violence are more likely to report higher numbers of lifetime sexual partners.35 Being a witness to community violence increases the likelihood of reporting intercourse while being under influence of alcohol or recreational drugs, having an earlier onset of sexual debut, having had sex with strangers, and testing positive for a sexually transmitted infection.36

Furthermore, high crime and the excessive incarceration of Black men in these communities have led to sex-ratio imbalances, which inadvertently promote male concurrency.37 Such imbalances also discourage marriage.38 In addition, these circumstances leave behind a much higher rate of single, nevermarried women as well as children without paternal support. The shortage of male partners within these communities has led to a phenomenon called “man sharing.”39 Those who engage in man sharing are women who (knowingly or unknowingly) have sexual relations with men who have other sexual intimates, a practice that complicates sexual health disparities.

The links between residential segregation and diminished physical and mental health for African Americans are well noted in the literature.40 Residential segregation of Blacks essentially accounts for higher incidences of chronic diseases, morbidity, premature mortality, and sexually transmitted infections. In Cincinnati significant differences in life expectancies, as well as disparities in sexual health, can largely be attributed to the neighborhood environment. In 2013 the Cincinnati Department of Public Health released statistics that demonstrated significant variability in average life expectancy by neighborhood. Those in neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty and an African American majority had a ten-year-shorter life expectancy, on average, than those in affluent white neighborhoods.41

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) also tend to be spatially uneven and significantly associated with segregated neighborhoods.42 In the Cincinnati Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), HIV/AIDS, for example, is concentrated mostly among Blacks in Hamilton County. Although Blacks represented only 27% of the county population, they accounted for nearly 70% of those newly diagnosed with HIV in 2012. Among women infected with HIV in this county, eight in ten are African American.43 These sexual health disparities in Cincinnati mirror the situation in many other urban locales throughout the United States, thus making Cincinnati a good place to study Black women’s sexual health risk.

METHODS

This qualitative study explores the implications of violence on Black women’s sexual health in Cincinnati. Twenty-five in-depth, semi-structured interviews with African American women residing in one of the highest STI/HIV-prevalent neighborhoods in the Cincinnati MSA informed this study. Participant observation was also utilized to understand neighborhoods as spaces. This study’s ethnographic approach solicited a nuanced understanding of African American women’s lived experiences in this urban, midwestern city. Ethnography is the most appropriate and reliable tool for uncovering how people are living within their social communities and how they understand and give meaning to their lived experiences. Ethnographic research is an organic process of discovery that reveals “complex interactions and connections among various contexts that frame the opportunities and constraints individuals encounter.”44

I conducted all but two of the interviews. A trained and experienced research assistant conducted the others. The in-depth interviews were collected between February 2013 and April 2014. The setting for the study was the University of Cincinnati, which is centrally located within an average of ten miles from the target neighborhoods and easily accessible via public transportation. Women participants were interviewed in a private interview room at the university.

The participant observations in the six neighborhoods were conducted with two researchers present on all occasions. Researchers explored on foot neighborhood streets and many venues, including health facilities, social service organizations, and merchants that participants had mentioned specifically during the interviews. Field notes were kept and helped inform the analysis.

Neighborhoods Under Study

All six neighborhoods canvassed in this study are situated in Hamilton County. Hamilton County contains the highest STIs and HIV prevalence in the Cincinnati MSA. Black women in this county account for 87% of women newly diagnosed with HIV and 75% of all women living with AIDS.45 While statistical summaries of chlamydia and gonorrhea are not available at the county level by race and gender, at the state level the rates for African Americans are 7.3 and 14.3 times greater than those for whites, respectively.

Neighborhood selection was based on a local newspaper article’s identification of the highest HIV-prevalent neighborhoods and zip codes in the metropolitan area.46 As summarized in table 2, nearly all these neighborhoods are predominantly African American, with high rates of concentrated poverty. Two of the neighborhoods with a white majority (Mapleville and Magnolia) contain census tracts or blocks with a Black majority. The average unemployment for Blacks in these neighborhoods was 23.5%, compared to 4.6% for whites. The average median household earnings were only $19,023, nearly $5,000 less than the national poverty threshold for a family of four in 2013. Most African Americans in these neighborhoods are renters. More than 90% of African Americans living in Pinewood in 2010, for example, rented their properties, which demonstrates well their vulnerability to housing insecurity, especially in wake of the gentrification surge. Finally, it should be noted that in 2009 in Cincinnati, nearly two in five violent crimes such as aggravated assault (38%), homicide (37%), and rape (36%) were concentrated in the six neighborhoods under study.

Table 2.

Cincinnati Black neighborhoods under study: Census characteristics, 2008–2012, and violent crime, 2009

| Neighborhoods under study | % Black | Unemployment rate % |

% Blacks living below poverty | Median household earnings | % Renters black | Marital status “married” % Black (F) | % of Violent crime by type in 2009 for Cincinnati neighborhoods under study* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black % | White | |||||||

| Pinewood | 48.50% | 28.60% | 5.50% | 58.40% | $13,164 | 94.10% | 6.50% | Aggravated assault=38.4%; Robbery=36.6%; Homo- cide=37.7%; Rape=36.4% |

| Cypress | 82.70% | 20.60% | 2.40% | 43.20% | $18,019 | 72.00% | 13.90% | |

| Cedarville | 61.61% | 29.30% | 5.80% | 49.60% | $15,410 | 80.90% | 10.10% | |

| Mapleville | 32.00% | 18.20% | 8.50% | 32.02% | $26,955 | 67.80% | 26.30% | |

| Magnolia | 17.00% | 16.23% | 3.40% | 45.30% | $20,697 | 75.00% | 14.60% | |

| Goodwood | 68.00% | 28.10% | 1.90% | 42.50% | $19,892 | 69.00% | 10.00% | |

To protect neighborhood anonymity, violent crime data are aggregated for all neighborhoods under study and presented by crime type.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, 3200S-2012, American Community Survey; Dan Wells, “Cincinnati’s Most Dangerous Neighborhoods,” Foxl9NOW-WIX, February 23, 2010, p. 1, http://www.foxl9.com /story/1202697S/cincinnatis-most-dangerous-neighborhoods.

Participants

Participant eligibility was determined by current neighborhood of residence and zip code, self-identified race, and gender. All study participants were HIV negative. A total of twenty-five women were interviewed, all self-identified as African American, biological women who currently resided in one of the six target neighborhoods. Participants responded to fliers posted in public venues, such as salons, barbershops, bus stops, coffee shops, public libraries, recreational centers, and health clinics, as well as word-of-mouth advertisement. Study participation was voluntary and confidential, and the identities of the participants were rendered anonymous at screening.

As summarized in table 3, the sample ages ranged between 19 and 67 years old, with a mean of 39.4 years. Participants were sexually diverse: 2 identified as lesbian, 2 identified as bisexual, and 21 identified as heterosexual. The sample’s average monthly earnings was $1,441. Half earned less $1,000 per month. Only 20% (n = 5) were employed, and 8% (n = 2) paid a mortgage on a house. The remaining 92% were renters, and 90% of those were receiving subsidies to support their housing. More than 70% of the women in the sample had had a prior STI, and all but 5 were currently in a sexual relationship.

Table 3.

Sample characteristics

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 39.4 | X |

| Monthly earnings | $1,441.00 | X |

| N(25) | % | |

| Currently employed | 5 (20%) | |

| Homeownership | N(25) | Percent |

| Homeowner (pays a mortgage) | 2 (8%) | 8% |

| Renter | 23 (92%) | 92% |

| Neighborhood of Resident | N(25) | Percent |

| Cypress | 5 | 20% |

| Magnolia | 3 | 12% |

| Goodwood | 6 | 24% |

| Pinewood | 5 | 20% |

| Cedarville | 3 | 12% |

| Mapleville | 3 | 12% |

Data Collection

The 25 in-depth interviews lasted between 60 and 180 minutes. The average interview was 135 minutes. The interview guide was structured around four main topics: (1) neighborhood context (resources, perception of, satisfaction with, networks within); (2) sexual intimacy (past and present sexual encounters; race, sex, age, and residing neighborhood of partner; infidelity; use of condoms and birth control; STD history); (3) being a Black woman (including privileges and restrictions, ways of coping, perspectives on how Black women relate to each other and to Black men); and (4) health (medical conditions, access to healthcare providers, perception of HIV/AIDS in the Black community, assessment of risk for HIV, health messaging, what it means to have a healthy life, etc.). The data used for this analysis came mainly from questions in the interview guide that asked participants about neighborhood context, sexual intimacy history, and knowledge and views on HIV/AIDs (see appendix).

All study participants provided informed consent and received US$50 in the form of a Visa giftcard for their time. Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. The accuracy of transcribed data was verified by the researchers, who listened to the recordings and read the transcripts simultaneously.47 The University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board approved the research protocol (#UC2013–385).

Data Analysis

The transcript data were re-read several times in their entirety so that a complete picture of the data could emerge. To capture the essence of life for women in these high HIV-prevalence Cincinnati neighborhoods, the raw data from the original transcriptions were coded to identify salient themes and patterns. As Miles, Huberman, and Saldana explain, “When we identify a theme or a pattern, we’re isolating something that (a) happens a number of times and (b) consistently happens in a specific way.”48 Violence (and various dimensions of violence) emerged as a universal theme throughout the sample. According to Braun and Clark, a thematic analysis requires: (1) becoming familiar with the data, (2) generating meaningful codes, (3) identifying broader categories or themes within a code, (4) reviewing and refining the themes, and (5) operationalizing and naming themes.49 Using Microsoft Excel, a single-page matrix was created to identify domains, themes, and subthemes of violence. The purpose of the matrix was to reduce the data into manageable units to permit cross-case comparison. Individuals were grouped based on similarities and differences in their experiences with violence. To achieve reliability, two researchers coded the data separately and then discussed any discrepancies in coding until consensus was reached.50 Field notes and reflections from participant observations were also utilized to support the analysis.

RESEARCHER REFLEXIVITY

I am a sociologist by training and a feminist by circumstance. As my identity as a feminist scholar solidifies, I find myself caught between two worlds, wrestling with a methodological conundrum. As a trained social scientist in the positivist tradition, I’m challenged and intrigued, and even enticed, by the idea of abandoning the loft y and perhaps unrealistic and fallible goal of neutrality. As a Black/Africana feminist scholar activist, I do not pretend nor wish to pretend to be disinterested in or, worse yet, dispassionate about injustices that Black women, children, and men endure daily in these United States. The singular aim of my current work and the methodological tools I employ is to give voice to the voiceless and visibility to the invisible.

As my Black feminist sensibilities have been cultivated, I have come to value the lived experiences of the Keishas of the world.51 Keisha is that sassy, outspoken, “honest” Black girl in Collins’s “Fighting words … Or Yet Another Version of the Emperor’s New Clothes” in her book, On Intellectual Activism. Keisha bravely declares out aloud: Mama, that white man is naked! In doing so, Keisha is immediately hushed, in part for her own safety by her mom and in part because her truth stands in “opposition” to the interests of the power elite and its court. Keisha is a truth teller, whose voice is generally unheard, whose face and body are rarely seen, and whose ideas are rarely published, read, or known. Keisha’s social location (as a poor little Black girl) disadvantages her in numerous ways but in particular with regard to access to the power elite. Not always fully aware of this disadvantage, Keisha speaks her truth to those who are willing to listen. I listened. And as a conduit, I present Keisha’s own words of her own story. And yet, before I do, I need to remind readers that while the women interviewed in this study are all selfi-dentified “Black” women, they are diverse along many dimensions, such as sexuality, social class, and neighborhood of residence; still, they have many commonalities with regard to health risk and spatial similarities. Though they are all Black and diverse, they do not represent all Black women in Cincinnati or Black women in general.

Born in the rural South, I come from the bayous of Louisiana. My formative years were spent in the countryside within the brace of my extended family, who were my neighbors and my entire social world. As such, I know little about the intimacies of living day-to-day in an urban, metropolitan city like Cincinnati, though I have worked in the city for more than ten years. As a Black woman, though I was different from the participants along some dimensions, such as social class and place of origin, there was still a strong feeling of connectedness, perhaps because race is so salient an aspect in American life that these other important identities are given less attention.

Participants were aware of my status as a university professor, which may have influenced their willingness to participate in the study. The fact that we were strangers did not seem to compromise their willingness to speak freely and honestly about their life experiences. Mario Small’s Someone to Talk to demonstrates this point well: that in fact, people often confide some of the most personal aspects of their lives to strangers as opposed to telling members of their “strong ties” networks.52 Small explains that relationships with close friends and family members are often “complex and fraught with expectations,” and as such, “the need for understanding or empathy exceeds the fear of misplaced trust.” As the data revealed, the dialogues in this study between participants and the interviewer were raw, honest, and transparent.

RESULTS

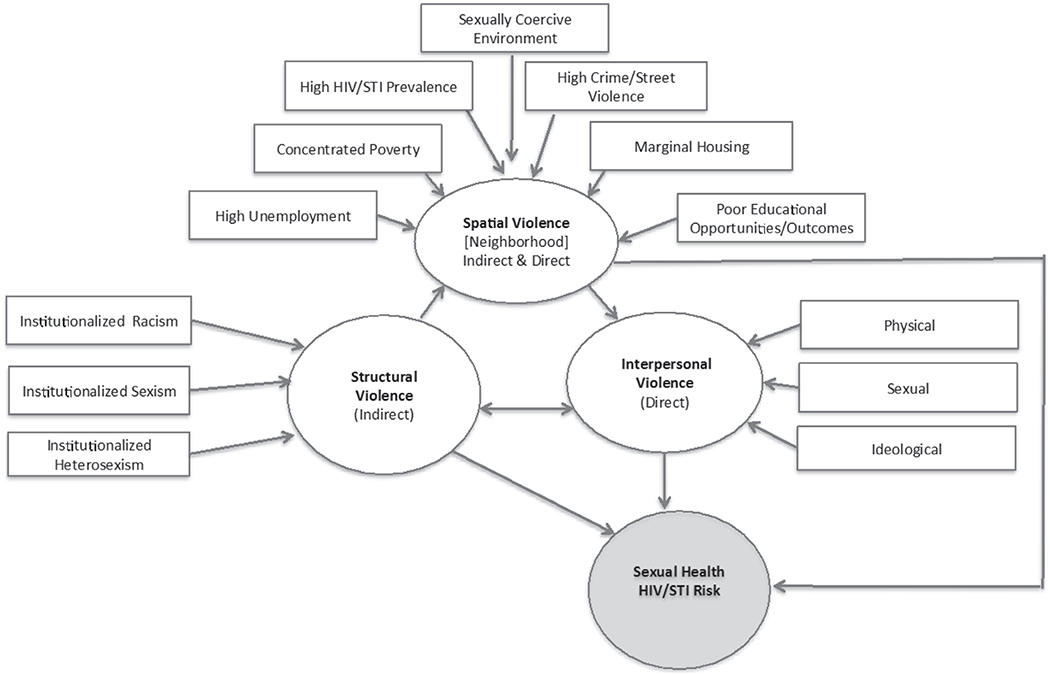

The study was designed to explore the day-to-day lives of Black women residing in HIV-prevalent neighborhoods. Though the interview questions focused on issues such as sexual history and health (namely STI and HIV risk perception), neighborhood characteristics, and so forth, participants voiced their experiences with violence at length. As a result, the overarching theme that emerged in this study was violence. Engagements with violence were not only co-occurring, but also intersecting and multidimensional.53 The term intersecting violence is used to capture the various levels of violence from the structural to the spatial to the interpersonal (see fi g. 1), whereas multidimensional violence refers to various ways women experience violence as observers, victims, and perpetrators. Women’s engagements with violence were physical, sexual, and ideological and more often than not reoccurred over the lifespan, leaving behind a significant and indelible imprint on their sexual health and risk for STIs and HIV/AIDS.

Figure 1 displays a conceptual ecological model that illustrates how violence is an intricately interwoven feature at three levels: macro (structural violence), meso spatial (community/neighborhood violence), and micro (direct or interpersonal violence). The types of violence that emerged from these data include: (1) community or neighborhood violence, (2) physical violence, (3) sexual violence and exploitation, and (4) ideological violence. While the first type is meso-level violence, the remainder are micro level; all are influenced by the context of structural violence. Though presented as separate categories here, incidents of violence in women’s lives often overlap and as such are difficult to compartmentalize neatly.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual map: Exploring dimensions of violence (structural, spatial, and interpersonal) on Black women’s sexual health and well-being in high HIV-prevalent Cincinnati neighborhoods.

Violence at the Meso (Spacial) Level: Violence in the Community or Neighborhood

Spatial (community or neighborhood) violence is well documented in these narratives. Although no specific interview question asked about violence, narrations of violence emerged primarily in response to the question what do you like and dislike about your neighborhood? Time and again, interviewees talked at length and in graphic detail about the everyday violence they encountered in the neighborhoods. Some spoke of friends or themselves being randomly shot, others spoke of random rapes in the alleyways. These cumulative acts of violence are devastating and often lead to self-isolation and disengagement. Lynn explains in a follow-up probe on her proclamation of being “lucky to still be here at 45 years” that unlike others, presumably in her neighborhood, she “at least” called the police about an alleyway rape she witnessed:

Lynn: [One] of my friends, she’s dead. She didn’t make it to 22, so, you know what I’m saying? I’m 45. It’s hard out—you’re in here. You’re not out there … I’m out there. I see things. I see all kinds of things. I see a girl in the alley one day; I lean back, she’s getting raped. At least I took a phone and called 911. In broad daylight. This stuff happens [here], you know what I’m saying? I move to Cypress. It doesn’t make a difference. It’s bad there, too.

Lynn’s recent move was not by choice but by circumstance: forced move due to gentrification eff orts. At the time of the interview, she rented an apartment in a building recently purchased by local hospital. As a result, she had to find a new place to live quickly. In the same breath, she explained how urban renewal eff orts were improving the cityscape in Pinewood and how things needed to change:

Lynn: Goodwood right now is cool. I’m moving into a house now—me and my dude. We have a house out in Cypress. We lucked up on that. That’s really nice. Pinewood is getting better now with the remodel and stuff. It’s real good, but it’s dangerous down there. I told you my nephew just died in April, just got shot out on Pine Street by the market in broad daylight. Shot him in his head … It was because he danced better than the [other] dude. It wasn’t about drugs, no girls. It was about dancing. You know, twerking, they were doing that—my nephew—you know.

As Lynn continued, she explained how the different neighborhoods are viewed from local perspectives and commented on the types of spatial violence people encounter:

Lynn: In Cypress, you have to be a night crawler. I’m not a night crawler.

Interviewer: What do you mean by a “night crawler?”

Lynn: People [who] are outside at 11, 12, 1, and 2 and 3. Crack cocaineing and, you know, crack cocaine and 40 oz. I don’t do that. I mean, Cypress—that’s why I [don’t] want to move back. Now, Goodwood—[people] are sneaky. Cedarville, they don’t give a fuck. They do all kinds of shit. It’s crazy. They’ll come up to you asking for a dollar. If you don’t, they’ll spit on you. Cedarville. They do that knock out game. Did you hear about that? Where they hit you just to see if you fall down? Oh, my God! That’s been on the news, too. You haven’t heard about that? People come for you and hit you, see if you fall down? Oh, my God.

Lynn’s narrative is rich in details about the spatial (community) violence occurring in the neighborhoods in which she resides and that she moves between. Implicated also are the structural violence, the politics of not caring and neglect brought on by city gentrification initiatives, which have caused yet another forceful shift in the Black populations across Cincinnati. And also implicated is the vulnerability and uncertainty of just being. The constant worry of being violated—of being spat on or knocked out at random—leads to weathering (e.g., accelerated health deterioration), which has been shown to adversely impact women’s reproductive health, such as with lower birth weight infants.54 In these neighborhood spaces where disadvantages are amplified and concentrated, violence of various forms seems to be everywhere.

Violence at the Micro Level: Violence by and Between Individuals

Physical violence.

Interpersonal violence of various types abounds, including physical, sexual, and ideological. A number of women talked about the violence they witnessed in their home: most often violence against their mothers, usually by their fathers or their mothers’ boyfriends. The most gripping and unsettling tale was told by Michelle, who witnessed her mother being violently killed by her boyfriend when Michelle was only five years old:

Interviewer: How did your mom pass?

Michelle: She was beat to death.

Interviewer: By?

Michelle: Her boyfriend. He said he felt like, [if he couldn’t have her], nobody [could]. He went to jail for a while; now he’s out.

Interviewer: Do you remember?

Michelle: I watched it. But I don’t remember it.

Interviewer: How old were you?

Michelle: Five. I don’t remember it. He introduced [himself to] me. I met him, and he apologized. But I just don’t talk to him.

Michelle’s life narrative was traumatizing to hear and difficult to process. By all appearances, however, she seemed to be emotionally intact and even somewhat light-hearted. It was not until later in the interview that she mentioned the seizures from which she now suffers (and which prevent her, by doctors’ orders, from being employed) that had started when she was five years old—just after her mom’s death. While possibly a coincidence, it seems rather likely that her seizures were a stress-induced reaction to having witnessed her mother’s tortured demise. Unable to be gainfully employed, Michelle now relies on disability checks and boyfriends to supplement her income and provide material comforts.

In addition to observing violence, some women in my sample also perpetrated violence.

Jill, who was sixteen and pregnant at the time, went visiting relatives in Pinewood when by happenstance she came across a woman who was rumored to be her boyfriend’s other “baby momma” (the mother of another child of her boyfriend):

Jill: Me and my god-sister, we walked to the store. She pointed out one of his baby’s momma. The girl came up to me like, “Oh, you pregnant.” … I’m like, “Yeah, whatever.” She like, “Oh, okay,” and then she started jumping [in my face]. [I said,] “What you getting mad for?” Like, what’s the problem? What’s the issue? Like, I want to know. And I did [let] my anger [get the best of me]. I punched her in her face, and we started fighting. She kicked me in my stomach … Wo, the next day I was bleeding so much I went to the hospital.

Interviewer: So, your miscarriage was a result of this woman kicking you? How old was this woman?

Jill: [Yeah]. She was probably 24. I think it was like his second baby momma. I found out a lot of stuff over the years about him. He got like six baby mommas, [and] probably about like eight kids.

Jill’s narration amply demonstrates the sexual competition between women and ultimately the “man-sharing” tendency (although unwelcomed and often unacknowledged) that has become so prolific within communities with off-balanced sex ratios, which incidentally accelerates the rate of STI and HIV infections.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) was also very common among the women in my sample, irrespective of sexuality. Often the IPV occurred when they were young, and many told horrific tales of torture and escape. In the narrative that follows, Tonya explained how when she was eighteen she followed an older man down to Mississippi:

Tonya: I stayed in Meridian [Mississippi] for a little while when I was 18. I moved down there with this guy; that’s when I got my apartment. And I really liked it down south until he jumped on me down there.

She explained how one night he wanted to go to a party in Jackson, but she did not want to go. The party was in the backwoods, “in the cuts” and “up the hills” along a dark road with no sidewalks or streetlights:

Tonya: So he got mad, and he beat me up.

Interviewer: Did he beat you bad?

Tonya: Yeah, he beat me up, but I had been there for five months, and I knew my way around. So, being a woman, I went to the women’s shelter, and they called my mom.

Interviewer: Okay. And, you were only 18 at the time?

Tonya: Yeah.

Interviewer: Now, did he beat you to the point where you needed to see a doctor?

Tonya: No.

Interviewer: Did you have anything broken?

Tonya: No.

Interviewer: Was there any blood?

Tonya: He just was … cutting me with a machete knife across my back, and I was ducking out [of] the way. But my mom and my dad sent me a bus ticket, and I got out.

Sexual violence and exploitation.

Michelle, the young woman who witnessed her mother’s murder, also experienced IPV as well as sexual exploitation. After bouncing around, living in her grandmother’s house and then with neighborhood men who were at least twenty years her senior, at age seventeen she found herself in the clutches of a sex trafficker from Florida.

Michelle: The one I ran away with and went to Florida, who wanted to pimp me out?

Interviewer: Yeah, let’s talk about him.

Michelle: Yeah. Everybody come to jazz festival. He was Puerto Rican with beautiful hair. “Come live with me. I’ll take care of you.” His accent was so sexy, so I’m like, Sure. I’m gone. I went down there and he tried to pimp me out. It was great for the first week. Then he tried to pimp me out.

Michelle: I met him at jazz festival. He took me to the hotel. We had sex that same day. It was great, terrific, excellent sex. I was like, wow. Then he started talking about going to Florida. I’m like, “Okay, I’m gone.” She explained that they drove down the very next day; she left with just a cell phone and no money in her pocket.

Michelle: For the first month it was so great. We had a personal relationship. We went out. We went shopping. He showed me around. Then the next month, he’s like, “Oh, I got about nine other girls who work for me. You should go out there and try.”

Interviewer: How old was this guy?

Michelle: 34. I was attracted to older guys. I don’t know why.

Interviewer: So, when he asked you to try this, how did he do it?

Michelle: He was like, “Do you love me?” I’m like “Why?” “Because if you love me, you would do something for me.” I’m like, “Sure, I love you.” He’s like, “My friend be looking at you, and he’d give you $600 to have sex. But he’s going to put it in my hand, and I’m going to give it to you when you come back.” So, then I said no. We got into a really violent fight. He hit me. He beat my ass. So, then my face was messed up for a while. I’m too ashamed to call home. Then he came back after I healed up, and he asked me again. We had great sex then. Then he came and asked me to do it again. And I’m like, “Sure.” Then I called my daddy.

Interviewer: So, did you have sex with the guy?

Michelle: No. I called my daddy. He cussed me out the whole conversation until I got home. Then he cussed me out some more, but he paid for my ticket home … I have could gotten him for statutory rape because I was so young, under age.

In the United States, sex trafficking is a multimillion-dollar industry in which Black women and children are disproportionally over- represented. Based on trafficking statistics, 40 percent of commercially sexually exploited victims are African American, and in Los Angeles County as many as 92 percent are Black.55 As Monique Morris in Pushout and Susan Burton and Cari Lynn in Becoming Ms. Burton illustrate, the “boyfriend to pimp” hustle that Michelle experienced is a usual part of the game, as are supplying drugs to young girls so that they become addicted and motivated to earn cash to support both their habit and their pimp.56 One of the unfortunate outcomes has been the mislabeling and criminalization of trafficked girls as “child prostitutes.” As Morris declares, this defies logic—children can’t be prostitutes; they can’t consent to sex, “which means that when they participate in the sale of sex they are being trafficked and exploited,” and this is usually done by older men.57,20

In Elizabeth’s case, the sexual molestation she had experienced lasted nearly a lifetime. It began when she was just eight or nine, when her father began to molest her sexually. Her mother was ill, suffering from brain cancer, and had herself been a frequent victim of her father’s violent tirades and rape. I asked if he had been abusive to the kids as well. She replied:

Elizabeth: He was abusive to me, too. He used to fondle me when I was young—like nine. I didn’t ever tell my mom, though, because I know it would hurt her, you know. And he also asked to have sex with me. He tried to stick his tongue in my mouth, kissing me. My sister watched him doing that. But I lied because my sister told my mom, “I seen Dad in the kitchen trying to stick his tongue in Elizabeth’s mouth,” and my mom was like—she came into the room. “Is he in there trying to kiss you?” They all just stood there. “You better not be doing that.” She was like, “Why are you trying to touch your daughter?” He was like, “What are you talking about?” He’d get mad and leave. There’s been times that he came in my room. He picked me up out of bed. He took me to the bathroom—tried to sexually abuse me. I wouldn’t say anything [because he threatened], “I’m going to do something to you and your mom.” So, I never told her.

Because of the frequent sexual assaults, she left her parents’ home as a teenager. She lived on the streets and battled addiction and depression, which resulted in her going in and out of jail. As an adult woman with few economic prospects, she found herself living in her father’s home once again. She and her adult son moved in to care for him. As an elderly man of seventy- five years, even in his dying days, he continued to make sexual advances:

Elizabeth: He said, “I don’t know why I want to have sex with my daughter.” He was looking at me in those types of ways—like he still wanted to touch me or something. And then, like, I bathed him, put his pajamas on or whatever and put him to bed. I came back up to check on him and he is buck naked. I said, “Why did you take your clothes off?” And he’d just be standing … looking at me. That kind of scared me, so I just go isolate myself from him. I didn’t want to leave him like that, because he was sick.

The extent of sexual molestation of children in the US is difficult to estimate, as incidents like these most often go unreported. Often young girls don’t even know what is happening to them or have the language to articulate it; worse yet, some fear they will go unheard or unbelieved, so they stay quiet. The silence is also driven by a fear of violating the code of racial loyalty, which protects Black men, keeping them out of the legal system, and yet it allows the predators to roam free. The prevalence of sexual molestation within the Black community has been addressed by Black feminist writers in fiction such as Sapphire’s “Precious” and in the real life stories such as Becoming Ms. Burton. Most children who are sexually abused (like Elizabeth, Precious, and Ms. Burton), are assaulted by a male relative, usually the father, stepfather, mother’s boyfriend, uncle, or an extended family member or friend.58

Ideological violence.

In addition to physical and sexual violence, women in this sample also frequently described what I term ideological violence. Ideological violence refers to being called out of one’s name (that is to say being insulted or redefined in demeaning terms). Galtung notes that direct violence occurs interpersonally and includes language, or verbal violence, including name calling, put downs, or humiliation.59 According to Patricia Hill Collins, the ideological oppression of Black women is perpetrated through controlling images; for example, the promiscuous jezebel or the angry black woman.60

During a participant observation in one of our neighborhoods, we walked past a two-storey building that housed four apartments. In the bottom-left window we noticed immediately the word “Bitch” written boldly and centered across the bottom apron of the windowsill. There was no one around on this fall weekday morning, but still, the space was speaking to us. It spoke loudly (as the words were very noticeable) and violently (as the words were meanspirited and disparaging) to all passers-b y: women, children, and men. What made this spatial graffiti more distasteful was the fact that the building sat just across the street from the Boys and Girls Club of Cincinnati. Thus neighborhood children en route to innocent play were subject to this blatant spatial violence every time they went to this recreational center. In this neighborhood children are not protected from ideological violence, even in broad daylight in public and child-oriented places. Over time, this kind of violence (ideological violence) becomes as “normal” and status quo as the other forms of violence occupying neighborhood spaces.

Neighborhood poverty and economic disinvestment leave working poor women with few options for finding employment in the formal economy.61 As such, a number of the women interviewed did what they had to do to survive, which sometimes meant tolerating a boyfriend’s abuse or exchanging sexual favors for a little cash. Some just used the “promise of possibility” that men’s acts of kindness might lead to something more substantial if it meant being able to afford a trip to the grocery store for food that week. Others, like Barbara, regularly engaged in transactional sex as a steady means of support. Barbara began prostituting as a teenager. Living under conditions of extreme destitution and neglect, she followed her mom’s footsteps:

Barbara: Like I said, [when] I was five years old my mother turned into a crack head. A prostitute just out on the streets, not taking care of home, not taking care of me and my sister. But when it progressed to that point I was 9 years old and my sister—we’re five years apart; she’s older so she was 14 years old—she was in the streets, too. Not as far as drugs but just being promiscuous. Like, she had her first baby at 14. So there were times when I’d be at home with nothing to eat, no running water—we’d have to go next door and turn on their water outside where the hose is to just get a bucket of water to bring it into the house to wash up.

One of the most heart-wrenching narratives told about surviving poverty came from Elizabeth. She explained how the neighborhood she lived in had no shortage of dirty old men ready to exploit young girls from families deeply compromised by poverty. In the narrative that follows, Elizabeth explained that the pain she felt watching her sick mom struggle to make ends meet prompted her to do what she needed to do to help put food on the table:

Elizabeth: The neighborhood I lived in was like ghetto—a bunch of older guys. There was wineheads and drunks and stuff. I used to be standing on the corner of my house. The elementary school was across the street. We had a park on the side. I had big breasts at the age of 8. “Ooh, I can’t wait for you to get grown.” “Come here little pretty girl” [the men would say]. I went to tell my mom that the old men on the corner keep whistling and hollering [at me]. My mom would go down there and say, “My daughter ain’t nothing but 12 years old and I never want you to touch her. I’m going to kill you. Don’t mess with her.” So, eventually I started sneaking. I saw my mom struggling to make ends meet. I would get the money from them and give it to my mom. She was like “Where’d you getting this money from?” I would tell her I went and worked for somebody so we could eat.

Elizabeth started doing this around age fourteen for the money, and in exchange, the men would provide alcohol and weed, fondle her breasts, and, once or twice, had sex with her. She explained that she hated doing this, because she knew she was lesbian or bisexual and preferred women to men, but did it just for the money, just to help out her mom who was ill and dying of brain cancer; she did it to help her family.

When women are forced or compelled through necessity to exchange sex for money, especially under-aged young girls with adult men, personal agency is virtually nonexistent. As such, their ability to negotiate safer- sex practices is severely compromised, which substantially elevates the risk for contracting an STI or HIV. When drugs are part of these interactions, risks are compounded. Rita, now clean, explained that when she did drugs, she occasionally engaged in prostitution to pay for her habit. Fully aware of sexual risk, she often provided her partners condoms but was unsure whether the condoms were used because she was high:

Interviewer: What prompted you to go in to get tested?

Rita: I just always get them every year. Yeah. I always do, because you know from my background and when I said I did that prostitution and stuff. I don’t know. For some reason it paranoids me. I don’t know. Sometimes—I always give the man a rubber, but sometimes when I was doing that shit—that crack, excuse me—it makes me so high that I don’t know if he put it on or not. All I know, I gave it to him, and we have to handle some business and I’m about to get me some more drugs.

Sexual assault or rape is a strongly interwoven feature of the AIDS epidemic.62 In socio-political environments where conflict and violence are amplified, so too is sexual victimization. Several women interviewed raised the issue of rape (n = 6, 20%)—some as victims, others as observers of rape within the neighborhood space, and one as a product of rape. In every case when rape was mentioned, so was the contraction of an STI. Rape occurred in the context of marriage and on dates. Two women discussed previously—Michelle and Elizabeth—were victims of statutory rape, as was Barbara. Barbara was raped at her multi-unit apartment complex when she was just sixteen:

Barbara: Oh, I had a real bad experience. Just trying to be grown. It was the summer of me being 16. I ended up running across this guy, call him Woody, who lived in the same complex as me, my mother, and my sister. He knew that I smoked [weed] so he was like, “Hey, you want to smoke or whatever?” I was like, “yeah.” So he’s like, “Well, let’s go to my car. Let’s sit in my car.” The car was parked in the parking lot. There was people walking around. It’s like late evening, probably around 9 o’clock or whatever. It was no red alarms to go off [for me]. So we went to his car; it was a two-seater. And we began to smoke. We smoked like two joints. Then he’s like, “Let’s get in the backseat.” I’m like, “For what?” He was like, “To just sit back there and continue to smoke.” He was like, “Well, you can stay in the front seat,” and he proceeded to climb in the backseat. So we continued to smoke some more, and upon me passing him the joint, like he grabbed me in the back seat and basically just raped me like, “You better not scream or anything, I’m going to shoot you.” And he had a gun. He didn’t point it at me, but he made it be seen. So like I said, there was people in the parking lot talking, just out there kicking it with their friends. I’m just looking at them like I cannot believe this is happening. But the windows were tinted. It was just a two-car door. I just sat back there, and he proceeded to have sex with me with no condom, and I ended up catching chlamydia. I was still a minor, so I had to go through my mom, but she thought it was my appendix. So when we finally got to Children’s Hospital the doctor told her, “Well, good news—it’s not her appendix rupturing—but she does have chlamydia.”

Barbara was not the only woman I interviewed with a story like this. Jill, who was eighteen years old at the time of the interview, explained while on a date with an older man she recently befriended in the neighborhood, she was raped after an innocent night of watching video games and smoking weed. In a conversation about using condoms, she explained that she always used a condom, except this one time when she found herself having non-consensual sex, and as a resulted ended up with an STI. She explained: “I felt some type of weirdness but I went to sleep, till when I woke up [and] he inside me. I’m like why you inside me? He like, you woke up and started feeling on me. I’m like in my sleep? Like Yeah, I’m like nah that can’t happen.”

It should be noted that Jill didn’t call this rape; I had to ask—”Did you think he raped you?” She said, “Yes, I did.” However, later when discussing her view on how Black women relate to each other, she explained that they relate through hardship and the “things we go through.” I asked, “Like what kinds of things?” She replied, “Like rape that there’ve been plenty of Black women that probably got raped. You meet another Black woman who got raped, y’all connect because you know how that feels. Or being a single parent raising just a child by yourself.” What struck me as odd was the presumed equivalency of the likelihood of a Black woman being raped and a single parent.

The ubiquity of rape was also oddly noted in conversation with Ida, a woman who self-identifies as bisexual and sometimes straight. In reply to my question “How do you describe yourself?” Ida said: “Bisexual. I really prefer myself as straight, but consider me bisexual.” I interjected, “It’s however you define yourself.” She continued, “I consider myself straight. Because, I don’t even consider her a girl. I don’t. Because, she’s never had sex with a guy. Never ever. Not even raped.”

Not even raped! The neighborhood prevalence of STIs and HIV/AIDS is in itself an inherent spatial risk. People living within these spaces have higher odds of becoming infected than individuals who reside in neighborhoods with less prevalence. As Barbara’s example so painfully demonstrates, spatial violence increases vulnerability to interpersonal sexual violence. Additionally, Jill’s and Ida conceptualization of rape and the expectation of rape are reflective of the sexually coercive environments that Popkin and colleagues have amply described.63 The multiple barriers and forms of violence Black women in Jim Crow communities face, as Kim Crenshaw notes, are fortified by the “imposition of one burden interacting with pre-existing vulnerabilities to create yet another dimension of disempowerment.”64

As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report notes, the intersection of IPV and HIV significantly increases in the presence of violence.65 For example, it notes that women in relationships with violence are four times more likely to contract an STI, including HIV. Moreover, children who are victims of sexual abuse and those who have had forced sex during adolescence are likewise at increased risk for STI and HIV. The children are more likely to have sex with multiple partners, with strangers, or with older men and sex while intoxicated or high, which lowers the rates of condom use.66

When asked what people in the community were saying about HIV/AIDS, however, many respondents reported that very little was said and that nearly no health messaging was advertised in their communities to caution residents about the prevalence of HIV/AIDS within their collective spaces. Over and again, many of the interviewees associated HIV/AIDS with gay men or downlow living.

Interviewer: Recently, there’s been a lot of talk about HIV and AIDS in Black communities. What are your thoughts on HIV and AIDS?

Mary: I have not seen it. Since I work where I work now, I come into contact with a lot of HIV/AIDS patients, and most of them is gay, actually. Most of them is gay, and pretty much in the hood, you never really have gay people. You never—so, my uncle actually died of AIDS.

Interviewer: Oh, was he gay?

Mary: Gay. He was gay.

In this dialogue, Mary attributed HIV to “gay” identity, but then disassociated homosexuality with hood-life, and yet in the same breath, she recalled her uncle who died of AIDS but also lived in “the hood” and was gay. The disassociation of HIV from African American neighborhoods and the belief (even in the face of contrary evidence) that HIV is a disease that only affects gay men continues to be a roadblock for prevention advocates.

The majority of the women in the sample had been tested at least once for HIV (n = 22), and many got tested regularly. Some were prompted to get tested after getting an STD from a cheating lover; others because of pregnancy. Many decided to include HIV testing as a part of their annual wellness examination. Michelle got tested yearly, because one of the men she dated revealed that he was bisexual:

Michelle: I was 18 when I moved in with this guy. I was in love again. I stayed with this guy for four months. Then I found out he was gay. So, I moved back in with my grandma until I was 19.

Interviewer: How did you find out he was gay?

Michelle: Because he asked me, “Can I bring another guy into the relationship?” I’m like, “another guy?”

Interviewer: Was it for you or for him?

Michelle: It was for him, and he wanted me to watch.

Interviewer: Watch him be penetrated or him penetrating the other guy?

Michelle: Both. He was like, “I just want you to watch.” So, I’m like, I’m watching them …

Interviewer: You actually watched?

Michelle: Yeah. I was amazed. It was so new to me. It was weird. I was like, “Wow. Wow!” First they started kissing each other. Then he started giving the other guy a blowjob. So then he was like, “These are some tricks you can use.”

Because of this experience of voyeuristic ménage-à-trois, Michelle also believed that the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Black community is due to “lots of undercover guys out there.” So, she said, “You should protect yourself. I will get tested once a year for AIDS.” Other respondents, like Hilary, who had taken a vow of celibacy, associated the HIV/AIDS problem with promiscuity: “Women need to slow down and close their legs, stop having sex. If they do that, then [there] would be less [HIV/AIDS] going around.”

DISCUSSION

Violence was one of the most salient features in the lives of the women residing in the high STI/HIV-prevalent Cincinnati neighborhoods canvassed in this study. Violence in the women’s narratives was so pervasive that it defied specificity along any particular social demographic characteristics. The women’s narratives amply demonstrate what many health researchers are beginning to recognize: place matters, especially when it comes to health and well- being.

The target neighborhoods in this study richly reflect the damage of institutionalized racism in the form of de jure and de facto residential segregation policies. The women in this study navigated this invisible (and yet evident) structural violence on a daily basis. This structural violence gave way to a variety of spatial vulnerabilities, including broken schools, high unemployment, marginal and unstable housing, street violence, and high crime rates.

This study finds that women’s experiences with violence are both multidimensional and intersecting. Women encounter violence as observers, victims, and perpetrators. Their engagements with violence took various and multiple forms—physical, sexual, and ideological. Also, more often than not, episodes of violence overlapped or intersected over their lifespan.

Although none of the women interviewed in this study were HIV positive, more than 70% had had at least one prior STI, and 40% of those had had more than two in their lifetime. The various levels (structural, spatial, and interpersonal) and dimensions (physical, sexual, and ideological) of violence that women encountered over the course of their lives substantially elevated their risk for HIV/AIDS. Violence and HIV risk intersect in many ways. As Varcoe and Dick find with rural, spatially segregated, Aboriginal women in Canada, this study also indicates that Black women’s experiences in Cincinnati are compounded by poverty and drug and alcohol use, all of which significantly elevate their risk exposure to HIV and other STIs.67

Underreporting of violence to legal and medical authorities can aggravate sexual health issues in significant ways. Much of the violence that women in the sample endured went unchecked and unpunished. The high underreporting of violence in the neighborhoods occurred most obviously, though not exclusively, when family members were abusers. The silence on abuse within Black families and within the Black community is deeply woven into frameworks of structural violence. One problem that an informant mentioned is the inability to trust law enforcement officers, who may victimize complainants with ideological violence instead of solving the problems. Also, because most US-born Black Americans continue to live in segregated and economically isolated communities, many live under a separate “street code.” In Cincinnati the street code is “snitches get stitches.” If you tell, there is a price to pay. This mantra applies to violence within and outside the home, as the cases of Elizabeth, Michelle, and Barbara demonstrated.

Another salient factor complicating and perpetuating the silence around violence—especially when it involves women as victims of Black men-initiated violence—is internal race relations, or “racial loyalty.”68 The institutionalized racism that created these urban reservations in the first place holds Black women hostage. As protectors of children and the men they love, they often fear the consequences of and are reluctant to put one of their own in the system.69 Thus, for example, the rapists of the women in my sample (n = 6) went unpunished and unreported. One of the consequences of sexual victimization—and likely a consequence of protective silence, if not financial poverty—was being infected with an STD that had gone untreated for extended period of time. This further complicates women’s health in a number of ways, from infertility to HPV/cervical cancer to greater susceptibility for acquiring HIV/AIDS.70

Portraying women as “nonviolent” and perpetual victims is problematic and a false representation.71 As demonstrated by the women in this study, women can and do perpetrate violence, although it is mentioned less frequently than male-perpetrated violence. Women in the sample perpetrated violence against both women and men. Often literature on violence and women focuses on women as victims—as women are more likely to be victims of domestic and intimate partner violence than men.72 Recent scholarly attention, however, is giving more attention to women as perpetrators of violence, which is an important contribution.73 Our view of women as potential victimizers as well as victims helps scholars map and understand the interstices of spatial violence.74

Ideological violence has always been a part of Black people’s narrative in the United States. Black feminists, such as bell hooks, Patricia Hill Collins, and many others, have written extensively about the ways that social institutions, most notably the media, frame Black women ideologically into categories of “controlling images.”75 These socially contrived images of Black women as mammies, jezebels, sapphires, welfare queens, bitches, whores, etc. are demeaning caricatures that devalue all Black women. Ideological forms of violence rob them of their dignity and are both latent and overt acts of oppression.76

Ideological violence is perpetrated spatially and interpersonally. Ideological violence was prominent both in the spaces inhabited and the day-to-day experiences of the women in the sample. The repetition of violence—be it verbal or physical, spatial or interpersonal—can degrade one’s sense of self-worth and trouble one’s peace of mind. Moreover, persistent encounters and exposure to violence can significantly compromise mental well-being, as Connie’s narrative so powerfully evoked.

When mothers are incapacitated, children are the most vulnerable. Perhaps the greatest risk factor for violence victimization in the sample was having a mother who was incapacitated in some way—herself a victim of violence, death, or illness. In narratives where violence was especially prolific, the mother’s ability to protect her daughter from harm was compromised, as illustrated in Michelle’s and Elizabeth’s narratives. In such cases, the daughters turned to the streets as young girls and were more often than not sexually exploited.

In regard to promiscuity and HIV, there is no shortage of victim blaming, even by victims themselves. Perhaps this is the internalization of the everpresent controlling image of Black women as hypersexual jezebels who are irresponsible agents of disease and misfortune. When Michelle called for women simply to “close their legs” as a solution to the HIV/AIDS problem in US Black communities, I was unsurprised. In my data, women mostly engaged regularly in HIV-preventive behaviors. More than 90% of them tested regularly for HIV and accurately identified the most common ways people become infected with HIV. In addition, many did use condoms, but as with most individuals who believe they are coupled in a monogamous relationship, condoms came off. Even then, a number of the women I interviewed discussed having gone with their partner to be tested. When condoms are off, risk for contracting an STI and HIV is heightened multifold, especially when a partner is a part of a high prevalence network.

Moreover, we must remain mindful that structural violence impedes health promotion. As Page-Reeves and colleagues explain, “In many cases, health-promoting choices are not an option, or they may not represent the most valuable strategy for an individual in the context of limited factors—regardless of whether other options are healthy or not.”77 The latter applies particularly to women who are in abusive relationships with partners or as young children who are within the clutches of sexual predators in their family home or in their residential neighborhoods. This is also true of heterosexual Black women who reside in neighborhoods with off-balance sex ratios, where man sharing becomes an unwelcomed reality for those who wish to be coupled or have someone they can turn to for physical love. The gender imbalance raises competition for partners and reduces women’s ability to negotiate effectively safer sex practices and condom use.78 To challenge spatial and interpersonal violence, the best remedy is locating methods and means to break the silence and encourage appropriate channels of communication and trust.

CONCLUSION

Structural, spatial, and interpersonal forms of violence endanger women—especially Black women in high poverty neighborhoods—in complex ways with regard to sexual health. Structural violence created urban reservations that are spatially vulnerable in terms of concentrated poverty, violence, and high STD and HIV prevalence. These intersecting forms of violence can seem overwhelming, and finding solutions to the compounding problems of violence appear daunting. Yet the issues can be addressed. Educational and job opportunities must be a part of the dialogue. Also, existing community institutions can be utilized to raise awareness of health issues and provide support.79 Community institutions with a specific mission to assist women in addressing and challenging community and interpersonal violence (including intra-racial and intra-gender violence in intimate or kinship relationships) are especially needed.

Perhaps the most glaring area of neglect observed, both in conversations with interviewees and during strolls in neighborhood spaces, is the conspicuous absence of HIV health messaging. Local and state departments of health should be urged to do more in these spaces to make people aware of prevalence risk. And certainly, this has to be done cautiously, so as to not stigmatize individuals or particular communities. Yet it should be done. On our strolls we saw health messaging about diabetes but no other illnesses. Only four of the twenty-five women interviewed said they saw messaging around syphilis, and one had seen messaging on HIV/AIDS. This is a problem, given the prevalence of STIs generally and HIV in particular and, more important, the spatial concentration of this disease within particular Cincinnati communities.

For far too long, health advocates have labored under the assumption that individuals in neighborhood communities like the ones featured in this study are simply ill-informed about risk, and as such, initiatives have focused mainly on augmenting knowledge and urging individuals to change social interaction strategies deemed “risky behaviors.” As the data in this study compellingly demonstrate, there is no knowledge desert concerning sexual risk. Moreover, many of the women do engage in HIV risk-reduction behavior, such as routine testing and frequent condom use. Like women in more affluent neighborhoods, women within these communities also have sex without condoms, especially within the context of romantic relationships believed to be monogamous. The difference lies in the spatial prevalence of the sexually transmitted infections. This spatial prevalence, coupled with the prevalence of spatial violence, undermines women’s sexual agency. This context, as well as the physical isolation that often accompanies residential segregation, collectively gives shape to the elevated HIV/STI risk for women in these communities. As such, it is imperative that prevention scientists and public health advocates begin taking structures and policies, as well as neighborhood places and space, into consideration when addressing the HIV/AIDS crisis in US Black communities.

IMPLICATIONS OF INTERSECTING VIOLENCE ON SEXUAL HEALTH AND HIV RISK.

Structural violence, defined as the physical and psychological harm that results from exploitive and unjust social, political and economic systems, is the shadow in which the AIDS virus lurks.

J. S. Mukherjee, “Structural Violence”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS