Abstract

The fastest growing age group in the United States is the 45 and older population.1 Due to the nature of the aging lumbar spine, a significant majority of this population will experience low back pain (LBP) and symptoms associated with lumbar spinal stenosis.2–7 Accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment is required if this particular aging group of our population is to maintain an active and productive life into their later years.

Introduction

According to the 2010 U.S. Census Bureau, the fastest growing age groups are: 45 to 64 (31.5%); and 62 and older (21.1%).1 This represents an interesting and important demographic trend as these groups begin to swell the ranks of the retired. Commonly referred to as the Baby Boomers, this generation is aging differently than their parents and grandparents. For the most part, they want to continue to work, travel and remain physically active well beyond the traditional retirement age.6,8 However, due to the age-related degenerative changes of the spine, a high percentage will experience low back pain (LBP) along with the symptoms associated with lumbar spinal stenosis.2–7 Physicians should be aware of this common condition and be able to accurately diagnose and treat this growing and aging population afflicted with stenosis so that these patients can maintain their active lifestyles and independence as best possible.

Understanding Stenosis

Stenosis literally means a narrowing, or constriction, of the diameter of a passageway. Stenosis of the lumbar spine specifically refers to a narrowing of the neural foramina and/or the spinal canal which compresses the nerve(s) and surrounding structures. Lumbar spinal stenosis is often the direct result of the complex changes of the aging spine; a process commonly referred to as Degenerative Disc Disease (DDD) as well as degenerative changes in the paired posterior joints of the lumbar spine.2,4–7, 9–11 (See Figure 1.) DDD occurs gradually as the intervertebral discs naturally dehydrate and narrow. Over time, there is a loss of disc space height and a hardening of the outer portion, or annulus, of the disc. The vertebral bodies experience increased loads as the disc spaces narrow resulting in further stress causing bone formation, lipping, spurring, and sclerosis. There can also be a bulging of the annulus and ligamentum flavum thereby further constricting the canal and neural foramina. In conjunction with age, there is a growing understanding of the genetic contribution in the development of DDD and stenosis.10,11 This genetic trait appears to cause an abnormality in collagen which may weaken the intervertebral disc making it more susceptible to load bearing stresses.12, 13 The combination of an aging, shrinking disc plus the genetic factors of a compromised disc seems to make these patients more prone to develop lumbar spinal stenosis as well as stenosis all along the spine and especially in the neck.

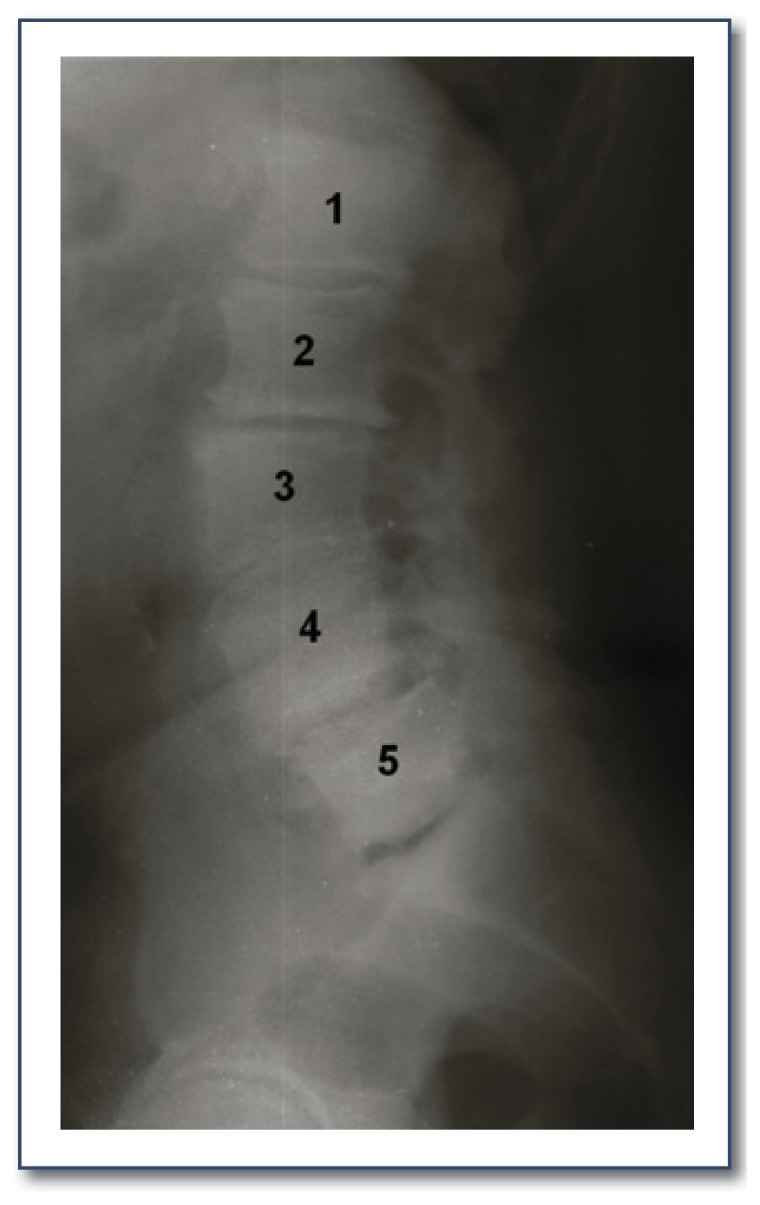

Figure 1.

Sixty-eight-year old male; Lateral radiograph showing diffuse degenerative changes

Stenosis can affect the nerve(s) as it exits the spine (Lateral Recess, Foraminal and Far Lateral Stenosis) or compress the dural sac (Central Stenosis). Because DDD and stenosis progress slowly, most patients normally seek medical treatment after age 50 and especially after the age of 60. They will typically present with a history of chronic LBP along with associated buttock, hip and leg symptoms of a more recent nature. At this point, a definitive diagnosis should be made.

Diagnosing Stenosis

It can be challenging to determine the etiology of LBP and extremity symptoms. Prior spine surgeries, genetics, peripheral vascular disease, peripheral neuropathy, diabetes, smoking, obesity and sedentary life styles need to be considered as contributing factors in this symptom complex. Unfortunately, peripheral vascular disease (PVD) can cause discomfort similar to stenosis. During the diagnostic process, it is important to differentiate between stenosis and PVD.

The characteristic symptoms of stenosis include LBP (but not always) and Neurogenic Claudication which involves unilateral or bilateral lower extremity pain, burning, cramping, numbness and/or tingling, tiredness and weakness. These symptoms will intensify with standing and walking, and will be relieved fairly rapidly with sitting. Bending forward will also be comfortable as flexion of the spine creates more space in the spinal canal and neural foramina.

PVD is a common circulatory problem that involves a narrowing of the arteries causing insufficient blood flow to the extremities. The symptoms can mimic stenosis (vascular vs. neurogenic claudication), but there are some subtle differences that require careful analysis of a patient’s history and presentation.2,5 Like stenosis, PVD can cause cramping, numbness, and tingling in legs which intensifies with walking. However, these symptoms will generally be relieved by stopping and just standing which allows more blood to flow into the extremities. In addition, pedal pulses may be weak or absent, the feet may feel cool and appear pale or bluish in color. Stenosis patients, on the other hand, will want to sit down and flex their lumbar spine to get relief. A certain percentage of patients will have both PVD and stenosis.

LBP is common and frequently not associated with stenosis. It is important to point out that the symptomatic course and treatment for LBP and stenosis are usually quite different. LBP without radicular symptoms may be mechanical and not neurological in nature. Mechanical LBP is typically self limiting with periods of flare ups and relief over time. Radiating leg pain may be the result of a crack or tear that develops in the outer annulus which allows disc material to escape causing a herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP). While this causes leg pain similar to stenosis, approximately 50% will resolve on their own. The prognosis for stenosis is different. Stenosis is more likely to get progressively worse over time because it is more closely linked with the continuous degeneration of the aging spine. Consequently, the treatment for stenosis should consider the natural history of the disease process and how it is different from that of an HNP. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2.

Sixty-five-year old female; MRI showing an HNP at L4–5.

Along with a thorough history and physical exam, radiographic studies may also play an important role in the diagnostic process. Plain PA and lateral lumbar spine films should be taken first to rule out tumors, infection, spondylolisthesis, scoliosis or a pars defect.2 Standing films and flexion and extension films should also be considered as these may reveal lumbar instability. Additional radiographic studies such as an MRI or CT should be considered only with patients exhibiting symptoms of the lower extremities. Both scans are excellent, non-invasive tests that offer views of the spinal cord, cauda equina and exiting nerve roots.6, 13–15 (See Figure 3.) The role of an MRI or CT scan is not just to confirm that stenosis is present but to help pinpoint the areas contributing to the symptom(s) and its severity. If an MRI is ordered and the patient has a history of previous surgery, it is important to request the MRI be done with and without contrast. Interpretation of data from these tests requires correlation with all initial diagnostic components and any additional tests. A specialist may be best qualified to transform the data into useful clinical information.

Figure 3.

Eighty-three-year old female; Myelogram (Left) and CT (Right) showing severe stenosis at L4–5 causing complete blockage of radiographic dye.

Treating Stenosis

A conservative approach should be the initial course of treatment for stenosis, especially in the elderly. Relief of symptoms is often seen with simply decreasing activities and the use of anti-inflammatory medications. Physical therapy and strengthening exercises can also be helpful. Cycling, typically stationary, because it involves lumbar flexion, is usually tolerated well by patients with lumbar stenosis.2,4,5,10,11 These conservative measures should be prescribed for at least eight to twelve weeks before considering them to be unsuccessful. Patience is an instrumental component of conservative therapy.

If there is little to no improvement with these conservative measures, epidural steroid injections may be considered. Unfortunately, it is not possible to predict if a patient’s symptoms will be improved, made worse or remain the same. If the injection provides significant pain relief, the patient’s symptoms may then be managed with modified activities and anti-inflammatories, and a daily flexion exercise routine.

Surgical intervention should be considered only after all conservative treatment options have been proven unsuccessful and the patient’s overall general health permits. In rare cases, rapidly progressive cauda equina syndrome or loss of bladder control should be treated as an emergency with immediate hospitalization and surgical intervention.

For those patients with unremitting symptoms, it is appropriate to consider surgical options. However, the role of surgery continues to remain somewhat controversial.2,6,7 Several peer reviewed articles report patient’s experience relief immediately following surgery, but regress to their previous pain situation in long-term follow-up when compared to an equivalent and comparable non-surgical group.3,4 The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) was another look at the outcomes of surgery vs. no surgery stenosis patients.14 Results of this study indicate that patients really do have a choice between surgical or non-surgical treatment. If surgery is chosen, the patient will improve greatly, but if they prefer not to have surgery, they can also see some improvement-it will just take more time.

After careful consideration and consultation with the patient, if surgery is the next step, options include time proven procedures (laminotomy, laminectomy, medial partial facetectomy, foraminotomy) as well as perhaps newer, minimally invasive surgeries (MIS) that are gaining acceptance. Recent developments in MIS are very appealing to the patient, but a successful outcome is dependent on proper patient selection: the right patient for the right procedure at the right level or levels.

In 2005, the X-Stop® Interspinous Spacer (Medtronic Inc, Sunnyvale CA) was approved for use by the FDA. X-Stop is designed to be implanted between the interspinous processes of the lumbar spine. It is designed to limit extension of the lumbar spine and minimize constriction of the neural foramina at the level or levels of stenosis. This device has been in use for six years and is generally reported to effectively and economically relieve the patient’s symptoms. (See Figure 4.) However, longer follow up is needed to determine endurance of symptomatic relief and implant survival.5,17–19

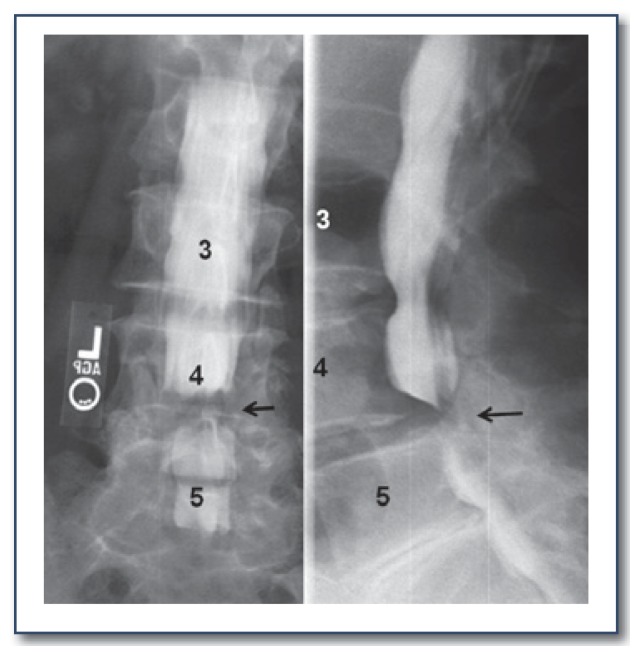

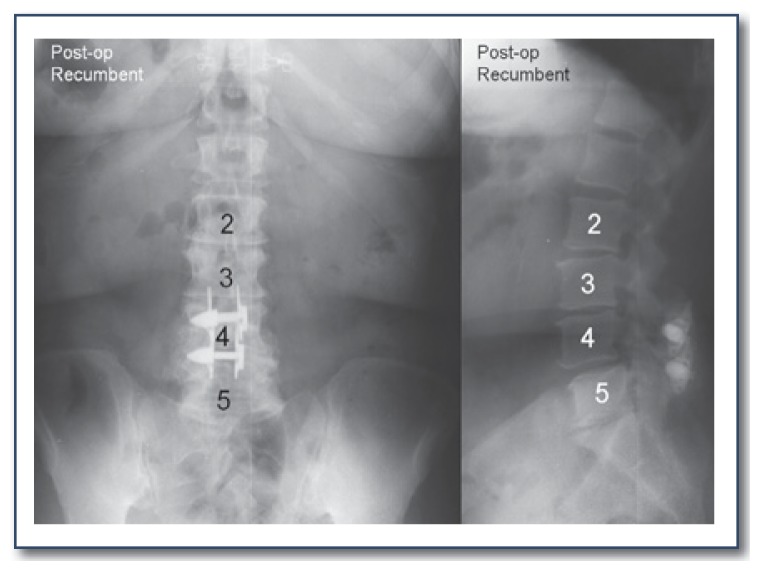

Figure 4.

Seventy-one-year old Female; Posterior/Anterior (Left) and Lateral (Right) radiograph showing placement of the X-Stop® Interspinous Spacer at L3–4 and L4–5.

In 2010, minimally invasive lumbar decompression (mild) devices (Vertos Medical, Aliso Viejo, California) were approved for commercial sale by the FDA. This is an outpatient procedure done usually under a local anesthetic and requires only a small incision through which fluoroscopic guided tools perform a limited laminotomy and tissue resection. The procedure usually lasts an hour or less and the incision can be closed with a sterile adhesive strip and no sutures. Although there is only one year follow up, the results have been promising.20–21 Again, however, long-term follow up is lacking.

For those patients with a diagnosis of spondylolisthesis and/or abnormal motion, a more invasive surgery, which would include spinal stabilization and even fusion, may be required. The role of spinal fusion is also a very controversial topic with varied outcomes reported in the peer-reviewed journals.7,22, 23

Conclusion

Among individuals eligible for Medicare, spinal stenosis is now the most common diagnosis among those having lumbar spine surgery. As the “Baby Boomers” enter retirement, their ranks will disproportionately increase the 65 and older age group. Because LBP and stenosis are intimately linked to the process of aging, the impact of LBP on society in terms of employment, recreation and health care costs will be substantial. Diagnosis and treatment of the aging spine are timely and topical issues, but there is not a consensus for standardized care. Current clinical and diagnostic research shows promise which will help lead the way toward proper and improved treatments. Newer, MIS procedures show promise too, but long term follow up is needed.

The “Baby Boomers” have had a long standing multifaceted impact on society; including education, housing and employment. Their years of retirement may prove to be an even bigger challenge to our country in terms of the health care industry. LBP and stenosis already create a substantial financial burden on our society. There is a need to develop a more standardized approach in the diagnosis and treatment of this difficult issue because as we know the “Baby Boomer” population explosion is just beginning.

Biography

Roger P. Jackson, MD, MSMA member since 1979, is certified by the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery and is an active member of several national and international spine societies. Dr. Jackson limits his practice to the surgical management of spinal disorders, associated with North Kansas City Hospital in Missouri. Anne C. McManus, RN, and Jill Moore, MBA, are with the Midwest Spine Foundation in North Kansas City.

Contact: roger.jackson@rogerpjackson.com

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported.

References

- 1.Age and Sex Composition: 2010. May, 2011. [Accessed August 19, 2011]. pp. 1–15. http://2010.census.gov/2010census/data/index.php.

- 2.Hilibrand A, Rand N. Degenerative Lumbar Stenosis: Diagnosis and Management. Journal of American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. 1999;7:239–249. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199907000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlas S, Keller R, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Surgical and Nonsurgical Management of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: 8–10 Year Results from the Maine Lumbar Spine Study. Spine. 2005;30:936–943. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158953.57966.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atlas S, Delitto A. Spinal Stenosis: Surgical versus Nonsurgical Treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:198–207. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000198722.70138.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman R, Nowak D, et al. Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. Current Orthopedic Practice. 2008;19:351–356. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Englund J. Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. Current Sports Medicine. 2007;6:50–55. doi: 10.1007/s11932-007-0012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeYo R. Treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis: a balancing act. The Spine Journal. 2010;10:625–627. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demographics of Aging. [Accessed August 19, 2011]. pp. 1–7. www.Transgenerational.org/aging/demographics.

- 9.Ray C. What is Spinal Stenosis? Oct 24, 2002. [Accessed 9-1-2011]. www.spine-health.com/conditions/spinal-stenosis/

- 10.De Graaf I, Prak A, et al. Diagnosis of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. Spine. 2006;31:1168–1176. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000216463.32136.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gevirtz C. Update on Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. Topics in Pain Management. 2010;25:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marini J. Genetic Risk Factors for Lumbar Disk Disease. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:1886–1888. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.14.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Modic M, Ross J. Lumbar Degenerative Disk Disease. Radiology. 2007;245:43–61. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2451051706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boden S. The Use of Radiographic Imaging studies in the Evaluation of Patients who Have Degenerative Disorders of the Lumbar Spine. JBJS. 1996;1:114–124. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199601000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herzog R. The Radiologic Evaluation of Lumbar Degenerative Disk Disease and Spinal Stenosis in Patients With Back or Radicular Symptoms. Spine. 1992;Chapter 21:193–203. Instructional Course Lecture 41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinstein J, Tosteson T, et al. Surgical Versus Nonoperative Treatment for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Four-Year Results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial. Spine. 2010;35:1329–1338. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e0f04d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zucherman J, Hsu K, et al. A Multicenter, Prospective, Randomized Trial Evaluating the X Stop Interspinous Process Decompression System for the Treatment of Neurogenic Intermittent Claudication. Spine. 2005;30:1351–1358. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166618.42749.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chao S. Interspinous Process Spacer. Technology Techniques in Orthopaedics. 2011;26:141–145. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skidmore G, Ackerman S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the X-Stop Interspinous Spacer for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. Spine. 2011;36:E345–E356. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f2ed2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basu S. Mild Procedure: Single-site Prospective IRB Study. Clin J Pain. :2011. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31822bb344. Published online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deer T, Kapural L. New Image-Guided Ultra-Minimally Invasive Lumbar Decompression Method: the mild procedure. Pain Physician. 2010;41:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sengupta D, Herkowitz H. Degenerative Spondylolisthesis: Review of Current Trends and Controversies. Spine. 2005;30:571–581. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000155579.88537.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinstein J, Lurie J, et al. United States’ Trends and Regional Variations in Lumbar Spine Surgery: 1992–2003. Spine. 2006;23:2707–2714. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000248132.15231.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]