Abstract

Infectious spondylodiscitis presents a diagnostic conundrum, and establishing the diagnosis often requires expensive testing and workup. But because of the potentially irreversible neurologic consequences and the great expense and time required to adequately treat this rare infection, establishing a diagnosis is paramount. Below, we present a representative case from clinical practice and examine the prevalence of certain signs and symptoms and the utility of various diagnostic modalities health care providers can use to accurately diagnose afflicted patients and avoid disastrous complications.

Representative Case

VS is a 52-year-old male who presented to the Internal Medicine service for a two-week history of gradually increasing axial low back pain that was worse with standing and physical activity. He described the pain as sharp in nature, and stated that his activities of daily living (ADLs) were impaired by pain. He denied any fevers or weight loss, bladder or bowel incontinence, urinary symptoms, radicular pain in his buttocks or legs, or weakness in his lower extremities. He had a past medical history significant for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (as well as hypertension and chronic renal insufficiency not requiring dialysis). Of significant interest, he had undergone lumbar puncture for unrelated issues approximately six months prior.

On admission he was afebrile, with normal vital signs. Palpation and percussion of his back revealed point tenderness over his mid-lumbar spine. Neurological examination of his bilateral lower extremities revealed 5/5 strength and normal sensation, no clonus, downgoing Babinski, and 2+ patellar and achilles reflexes. His CBC did not show leukocytosis, left shift, or increase in any particular leukocyte cell lines, but his ESR was elevated at 122. His CT scan on presentation showed a destructive lesion in the L3–L4 disc space and both adjacent vertebrae.

The patient was subsequently admitted for spondylodiscitis, and blood cultures were drawn at that time. An MRI was then done to further image adjacent soft tissue and evaluate for the possibility of an epidural abscess but did not reveal anything further than the results of the CT. Antibiotics were held for his first hospital day until we could obtain a CT-guided needle aspiration of the lesion to yield a microorganism. He was then started on IV Vancomycin for empiric coverage. Unfortunately, neither cultures of the lesion nor his blood grew any organisms.

After he showed clinical and improvement, the patient was subsequently discharged home with a six-week course of IV Vancomycin for empiric coverage of MRSA, as staphylococcal species represent the largest percentage of identified organisms in patients with spondylodiscitis and because 75% of s. aureus isolates in our institution are methicillin resistant.

Pathogenesis

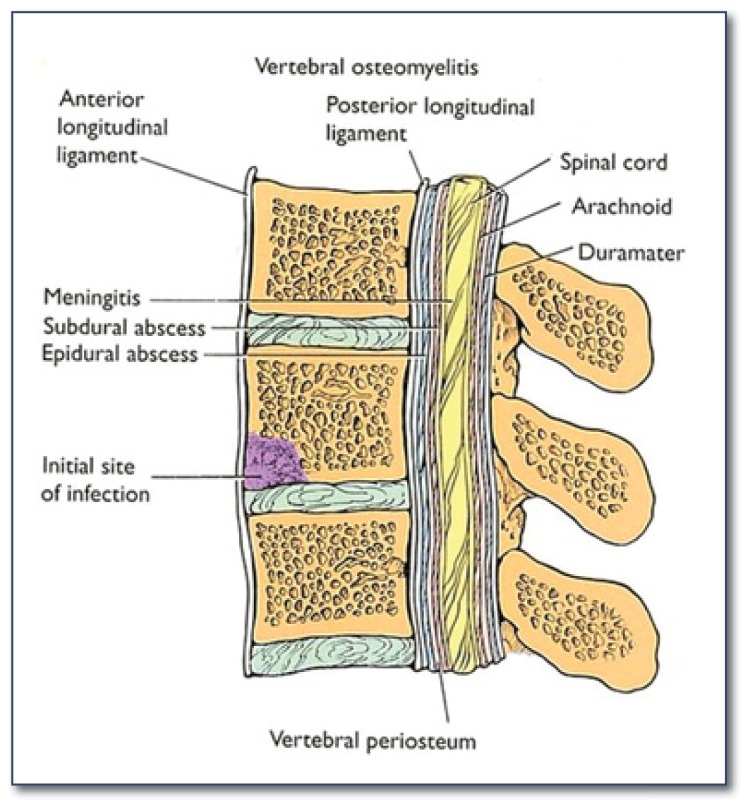

It is important to note that truly isolated “discitis” and “spinal osteomyelitis” most likely represent different stages and levels of progression of spondylodiscitis- an infection of both the intervertebral disc and the adjacent vertebrae1 (See Figure 1). The disease begins after inoculation of the spinal column by three distinct routes: a) Direct contamination by penetrating trauma or spinal surgery b) Contiguous spread from adjacent soft tissue infection or c) Hematogenous spread from a distant source of infection.2–4

Figure 1.

Spondylodiscitis- an infection of both the intervertebral disc and the adjacent vertebrae.

Careful elicitation of the patients history will reveal any recent sources of direct contamination such as lumbar puncture, discography, corticosteroid injection, epidural injection or catheterization, vertebroplasty/kyphoplasty, and of course recent spinal surgery.4

Patients who manifest disease from contiguous spread will often have clinically or radiographically evident nearby infections such as cellulitis, soft tissue infection, recent rectal surgery, or adjacent upper urinary tract infection.1,2,4,5

Because it is both the most common and arguably the least evident cause, a more in-depth search is needed to reveal a distant source of hematogenous spread of microorganisms, such as distant cellulitis, genitourinary tract infection, infected intravenous catheters, bacteremia, endocarditis of both native and mechanical prosthetic heart valves, diverticulitis, or even from normal oral flora after dental procedures or tooth brushing. In fact any true, or even transient, bacteremia may provide the nidus for infection.1–4, 6

In cases of hematogenous spread, the sludging of blood flow that occurs in the metaphyses of the vertebral bodies near the end plates provide a great opportunity for bacteria to seed and subsequently develop infection.1,4,6,7

Patient Demographics and Predisposing Factors

Though the reported rates of certain predisposing factors are often limited by the relatively small sample size of many of the trials, certain reproducible general principles are important to keep in mind in the clinical setting. Men are more likely to develop spondylodiscitis, with some authors citing a 1.5–3:1 preponderance of males.1, 2, 5, 7–10 Age is another important predisposing factor, as it is for many infections. Some authors report that 75% of patients with hematogenous spondylodiscitis are older than 50–65 years of age.1–3, 5, 7–11 Diabetes mellitus and its resultant immunosuppression are present in 18–66% of afflicted patients.1–5, 10 Other immunosuppressed conditions are common as well; some reports cite coexisting cancer in 25% of patients. One should look for chronic steroid use, anti-rheumatic medications, or other potential causes of immunosuppression. Intravenous drug abusers are more predisposed to developing spondylodiscitis because of frequent transient bacteremia.1–4

Two additional predisposing factors must be sought out by the physician: a) A history of recent injury or trauma (even non-penetrating). The theoretical explanation is that any vertebral injury causes an increase in local vascularity and fosters hematogenous spread to vertebral bodies. b) A history of a recent invasive procedure. Any GU or oral manipulation, IV injection or insertion of peripheral or central lines, non-spinal surgery, etc. may cause a transient bacteremia that may seed the vertebrae.1–4, 11

Symptoms: Fever, Back Pain, Spinal Cord or Nerve Compression

Fever

Like many other slowly progressive infections, fever is poorly sensitive for spondylodiscitis. Many studies have verified that fever is present in only 52–68%, though the latter number comes from a study that considered “fever” as greater than 37.5 degrees celcius, rather than 38.0 (Hopkinson). The absence of fever should not dissuade the healthcare provider from considering and appropriately working up spondylodiscitis.2,11,12

Back Pain

Focal back pain, especially in the lumbar region, is the single most common physical exam finding in patients with spondylodiscitis, present in >90% of patients.2,3,11 Often they exhibit point tenderness or pain upon percussion of affected vertebral bodies. The length of symptoms is often very important in this disease because most patients present with a subacute or chronic length of duration. Though this disease does represent a true osteomyelitis, its progression is often slower than osteomyelitis found elsewhere. One study found that the mean duration of symptoms at the time of diagnosis in 64 patients was 48 days with a large range of ± 40 days.2

Spinal cord or Nerve Compression

Studies report an incidence of neurological compression in 33–59% of patients. This most commonly is apparent as radicular compression with consequent uni- or bi-lateral weakness, parasthesias, or paralysis. Neurological symptoms should raise the clinician’s suspicion of mass effect from an abscess in the epidural space. The prevalence of abscess formation is varying, but cited in the literature as 35–74%.2,5,11 A study from a neurosurgical unit reported abscess formation in 74% of patients, but obtained a CT or MRI in less than 80% of the total patients, but did so routinely in all patients with neurological symptoms.

Though likely not representative of patients in a primary care setting, one study from a neurosurgical unit demonstrates the seriousness of neurological sequellae with abscess formation: 63% of patients (17 of 27) had significant neurological findings on admission (13 with paraparesis, 1 hemiparesis, 2 tetraparesis); all of these had abscess formation with spinal cord compression.5 Another study by Kapeller11 et al. showed that 59% presented with signs of radicular compression, and 29% with cord compression.

Laboratory: Leukocytosis, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR), Blood Cultures

Leukocytosis

The same principle holds true here as it does for the presence of fever. Often times, far too much stake is placed in the presence or absence of an elevated white blood cell count, despite that only 36–61% of patients with spondylodiscitis present with Leukocytosis.2, 5, 11 It is worth noting that leukocytosis is more common in patients with MRI confirmed abscess formation.

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate

Many studies have shown that an elevated ESR is present in 76–>80% of patients with spondylodiscitis.2,4,5,11 Although its sensitivity is not optimal and its specificity is certainly questionable, this does confer a good negative predictive value for normal results. For this reason, it is often used as a low-cost screening tool for spondylodiscitis.

Ninety-one percent of patients have an ESR >50 and 63% of patients had an ESR >100. And like the finding of leukocytosis, an elevated ESR is far more common in patients with epidural abscess formation (35 of 35 patients, in one study).3 It’s use also extends beyond that of diagnosis: it can be followed serially to evaluate response to antibiotics and improvement, particularly in those patients with no isolated organism who were given empiric antimicrobial therapy.13–15

Blood Cultures

Though hematogenous dissemination is the most common source of infection, blood cultures are frequently negative. It is important to remember that a transient bacteremia, not overt bacteremia, is often the culprit in seeding the vertebrae. Most sources report the prevalence of positive blood cultures to be 55–75%.1–3 Though not ideal for establishing the diagnosis, it should be performed routinely as it may guide antibiotic therapy.

Imaging: X-Ray, CT Scan, Radionuclide Imaging, MRI

X-Ray

Radiographs, though helpful, have limited utility in this clinical disease because of the delay in appearance of characteristic findings. When present, a destructive lesion involving two adjacent vertebrae with collapse of the vertebral bodies and the intervening disc is highly suggestive of spondylodiscitis. Other findings include end plate irregularity, defects of the subchondral portion of the end plate, and hypertrophic/sclerotic bone formation. And since it may clinically be evident as isolated osteomyelitis, involvement of an isolated vertebra is possible; this may falsely appear merely as a vertebral compression fracture. Initial findings are not present for the first two to three weeks of symptoms and will thus provide false negative results.4,17,18 Suggestive radiographs are only present in only one-third of patients.3

CT Scan

Most authors agree that CT provides little benefit over other imaging modalities (MRI or bone scintigraphy) in this disease process, and is primarily used in guidance for biopsy.4 CT is suggestive of the diagnosis in two-thirds to three-fourths of the time. In chronically afflicted patients, CT scans are nearly as sensitive as MRI scans, but are much less so in acute diseases.3, 7, 18, 19

Additionally, because of the widely accepted inferiority of CT scans in identifying soft tissue abnormalities, they have a poorer sensitivity in detecting epidural abscess formation.19 In patients with neurological symptoms, MRI is necessary.

Radionuclide Imaging

Bone scans are one of the most sensitive tests in detecting patients with spondylodiscitis. Multiple reports cite sensitivity of 90–95%. Despite the excellent sensitivity, the downfall to this approach is the poor specificity of this imaging modality. Bone scans are positive for multiple other reasons, many of which can mimic spondylodiscitis radiographically and clinically: compression fracture, neoplasm, advanced degenerative disk disease, etc. In addition, they are unable to detect abscesses. Bone scans are largely reserved for patients who are unable to undergo MRI because of pacemakers or metal artifact from adjacent hardware.3,5

MRI

MRI has largely become the imaging modality of choice in patients who are able to undergo the procedure. Characteristic findings include decreased signal intensity and loss of height in vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs on T1 images, and increased signal intensity in the discs on T2 images, though increase signaling in the vertebrae is common as well. With contrast enhancement, the involved vertebrae and the disc both enhance; if ring enhancement is seen in the epidural or paraspinal space, this indicates abscess formation.

MRI has supplanted other imaging modalities for a multitude of reasons. First of all, its sensitivity is superior to most other imaging modalities and at least equivalent to bone scans. One of the largest case series, of 103 patients, reported a sensitivity of 91% in patients with symptoms less than two weeks, and a sensitivity of 96% in those with symptoms longer than two weeks.14 Additionally, multiple sources3,4,9,14,19,20,25 have pointed out that MRI is greatly superior to other imaging techniques in providing detail of the soft tissues, allowing detection of epidural abscesses, which is principally important in those with neurological symptoms. Though CT scans may provide some soft tissue detail, particularly if performed with contrast, they are poorly sensitive in the acute phase. And though they may be the most sensitive technique, bone scans cannot provide information on the status of soft tissues nor can they differentiate from other differential diagnoses.

Direct Isolation of Organisms

CT-Guided Biopsy/Aspiration

Though this technique may be fruitless from a microbiological standpoint, it is still of critical importance. The utility of obtaining a tissue specimen is two-fold: culture and histology:

Culture

The cited rate of isolating an organism from culture varies according to source, with most authors reporting 50% to 75%.1,4,5,7,8,21–23 Even in experimentally inoculated sheep, all of which developed clinical infection, the yield rate of culture was only 37.5%, with most positive cultures coming from weak growth in broth medium only.24 Multiple studies confirm that biopsies performed before initiation of antibiotics yield a causative organism near 75–80% of the time, while biopsies performed after initiation of antibiotics yield a causative microorganism near 50% of the time.22

Histology

This modality is highly sensitive in detecting the presence or absence of spondylodiscitis but fails in addressing the causative organism and may also be suggestive of spondylodiscitis in patients who do not truly have the disease. Classic histologic findings include bone marrow fibrosis, plasma cell and lymphocyte infiltration, and vascular proliferation. Multiple studies report the sensitivity of histology between 81% and 90% and the specificity between 75% and 100%.7,8,21

Using both pathologic examination and culture of the biopsy greatly improves the yield in establishing the diagnosis. Either histology or culture is positive in 95% of patients with spondylodiscitis, and histology and culture are positive in 78% of patients.7, 8, 21

Summary

Establishing the diagnosis of spondylodiscitis is often difficult to do and is frequently done on presumptive evidence. In patients with suspected spondylodiscitis, one should of course begin with a thorough history and physical exam, specifically seeking out the course of illness, predisposing conditions, and any history of “invasive” procedures that may have led to transient bacteremia. A careful neurologic examination is paramount, as compression from an abscess may lead to irreversible damage. It is important to remember that the absence of fever, leukocytosis, and positive blood cultures does not rule out the diagnosis. An elevated ESR is one of the most sensitive indicators of an infectious process, but can be elevated for other reasons as well.

When considering imaging, plain films may suggest the diagnosis, and bone scans and CT scans are very sensitive. Unfortunately bone scans are highly non-specific and CT scans do not show adequate soft tissue detail. MRI is highly sensitive and much more specific than other imaging modalities and moreover provides much better visualization of soft tissues; as such, all patients with neurological symptoms should undergo an MRI.

Patients should undergo CT-guided biopsy of suspicious spinal lesions. Histological examination of specimens is a sensitive measure, and though the yield of culture is suboptimal, attempting to isolate a causal organism is a necessity in guiding antimicrobial therapy.

Biography

Michael H. Amini, MD, is a Resident in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Tennessee – Memphis. Gary A. Salzman, MD, (above), MSMA member since 2007, is Professor of Medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at the University of Missouri – Kansas City School of Medicine.

Contact: salzmang@umkc.edu

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported.

References

- 1.Perrone C, et al. Pyogenic and tuberculous spondylodiskitis (vertebral osteomyelitis) in 80 adult patients. Clinical Infectious Disease. 1994 Oct;19(4):746–50. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nolla JM, et al. Spontaneous pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis in nondrug users. Seminars in Arthritis and Reumatism. 2002 Feb;31(4):271–278. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.29492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hopkinson N, et al. A case ascertainment study of septic discitis: clinical, microbiological and radiological features. Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 94:465–470. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/94.9.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sexton D, McDonald M. Vertebral osteomyelitis. 2008 Mar 28; Up to Date. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hadjipavlou AG, et al. Hematogenous pyogenic spinal infections and their surgical management. Spine. 2002 Jul 1;25(13):1668–1679. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher GW, Popich GA, Sullivan DE, et al. Diskitis: a prospective diagnostic analysis. Pediatrics. 1978;65:543–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucio E, et al. Pyogenic Spondylodiskitis Archives and Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 124(5):712–716. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0712-PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chew FS, Kline MJ. Diagnostic yield of CT-guided percutaneous aspiration procedures in suspected spontaneous infectious discitis. Radiology. 2001;218:211–214. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01ja06211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cusmano F, et al. Radiologic diagnosis of spondylodiscitis: role of magnetic resonance. Radiologia Medica. 2000 Sep;100(3):112–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asamoto S, et al. Spondylodiscitis: diagnosis and treatment. Surgical Neurology. 2005;64:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapeller P, et al. Pyogenic infectious spondylitis: clinical, laboratory and MRI features. European Neurology. 1997;38(2):94–98. doi: 10.1159/000113167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sapico FL, Montgomerie JZ. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: report of nine cases and review of the literature. Clinical Infectious Disease. 1979;1(5):754–776. doi: 10.1093/clinids/1.5.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beronius M, Bergman B, Andersson R. Vertebral osteomyelitis in Göteborg, Sweden: a retrospective study of patients during 1990–95. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:527. doi: 10.1080/00365540110026566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carragee EJ, Kim D, van der Vlugt T, Vittum D. The clinical use of erythrocyte sedimentation rate in pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. Spine. 1997;22:2089. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199709150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unkila-Kallio L, Kallio MJ, Eskola J, Peltola H. Serum C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and white blood cell count in acute hematogenous osteomyelitis of children. Pediatrics. 1994;93:59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:369. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold RH, Hawkins RA, Katz RD. Bacterial osteomyelitis: findings on plain radiography, CT, MR, and scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:365. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.2.1853823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopecky KK, et al. Pitfalls in computed tomography in diagnosis of discitis. Neuroradiology. 1985;27(1):57–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00342518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.An HS, Seldomridge JA. Spinal infections: diagnostic tests and imaging studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:27. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000203452.36522.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stosis-Opincal T, et al. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of postoperative spondylodiscitis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2004;61(5):479–483. doi: 10.2298/vsp0405479s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel SC, et al. CT-guided core biopsy of subchondral bone and inter vertebral space in suspected spondylodiscitis. American Journal of Roentgeniology. 2006;185:977–980. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grados F, et al. Suggestions for managing pyogenic (non-tuberculous) discitis in adults. Joint Bone Spine. 2007 Mar;74(2):133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garron E, et al. Nontuberculous spondylodiscitis in children. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 2002 May-Jun;22(3):321–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fraser RD, Osti OL, Vernon-Roberts B. Diskitis following chemonucleolysis: an experimental study. Spine. 1986;11:679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Acker JD, Wood GW, III, Moinuddin M, et al. Radiologic manifestations of spinal infection. State Art Rev Spine. 1989;3:403. [Google Scholar]