Abstract

Aims

Bowel symptoms, pelvic organ prolapse, and sexual dysfunction are common, but their frequency among women with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) has not been well described. Our aims were to describe pelvic floor symptoms among women with and without urinary incontinence (UI) and among subtypes of UI.

Methods

Women with LUTS seeking care at six U.S. tertiary care centers enrolled in prospective cohort study were studied. At baseline, participants completed the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20), Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-IR), and PROMIS GI Diarrhea, Constipation, and Fecal Incontinence Scales.

Results

Mean age among the 510 women was 56.4 ± 14.4 years. Women who reported UI (n=420) had more diarrhea and constipation symptoms (mean scores 49.5 vs 46.2 [p=0.01] and 51.9 vs 48.4 [p<0.01], respectively) at baseline. Among sexually active women, mean PISQ-IR subscale scores were lower among those with UI (condition specific: 89.8 vs 96.7, p<0.01; condition impact: 79.8 vs 92.5, p<0.01). Women with mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) (n=240) reported more prolapse symptoms, fecal incontinence, and worse sexual function compared to those with stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI).

Conclusions

Women presenting with LUTS with UI reported significantly worse constipation, diarrhea, fecal incontinence, and sexual function compared to women without UI. In women with UI, sexual function and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) symptoms were worse in those with MUI compared to SUI and UUI.

Keywords: constipation, fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, urinary incontinence

Introduction

Symptoms of pelvic-floor disorders including constipation, diarrhea, and fecal incontinence as well as pelvic organ prolapse and sexual dysfunction are common in women. These disorders occur concurrently with urinary incontinence (UI); however, the relationship has not been well described. Pelvic floor dysfunction is common to all of these disorders which is why aging and childbirth which both affect the pelvic floor are factors that concurrently affect multiple pelvic floor organs in adult women. It has been reported that women with difficult defecation have more urinary urgency and frequency, but not UI; however, this is controversial1. Women with obstetrical anal injury are at increased risk not only for fecal incontinence but also stress urinary incontinence (SUI)2.

Pelvic organ prolapse has consistently been associated with urinary urgency and urgency incontinence (UUI), with the relationship possibly being causal since correction of the prolapse or placement of a pessary can relieve these bladder symptoms3. Also, the relationship between prolapse and SUI is complex, as SUI often occurs concurrently with prolapse, but prolapse may also be protective as correction of prolapse often unmasks occult SUI 4.

The association between UI and sexual activity remains uncertain. Prior studies have provided conflicting results, with patient age and partner status as possible significant factors5,6. Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) has the greatest negative impact on sexual function compared to SUI and UUI7.

The aims of this study were: 1) to determine the relationships between bowel symptoms including constipation, diarrhea, and fecal incontinence, prolapse symptoms, and sexual function among women seeking care for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS); and 2) to evaluate whether the presence of UI, or UI subtype, is associated with the severity of these symptoms.

Material and Methods

Study Design and Population

We report on women enrolled in a one-year, multi-center, prospective observational cohort study from the NIH/NIDDK-sponsored Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN). Details of this cohort study have been previously reported 8. Briefly, participants were at least 18 years of age, presented to a LURN physician for the first time seeking care for their LUTS, and reported at least one LUTS Tool9 symptom using a one-month recall screening period. We modified the LUTS Tool, with permission from Pfizer, to capture a recall period of one month for the LURN study. Data collection at the baseline visit for women included a standardized clinical examination including pelvic examination with Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantitation (POP-Q), assessment of pelvic floor muscle strength with the Oxford scale, urinalysis, and measurement of post-void residual. Medical history including functional comorbidity index (FCI), patient-reported symptoms of LUTS, pelvic floor symptoms, and psychological symptoms was also collected. Quality of life was obtained by validated questionnaires 10–13.

Measures

Seven questions regarding UI on the LUTS Tool 9 were used to determine presence of UI. Women who reported “rarely” or “never” to these questions were classified as “without UI”, and responses of “sometimes” or greater on at least one symptom of UI during exercise, laughing/sneezing/coughing, feelings of urinary urgency, sleep, sex, or for no reason were classified as “with UI.” Participants were further classified as having SUI if they answered “sometimes” or more on at least one of two questions related to experiencing leakage while exercising or during a laugh, cough, or sneeze. Those who responded “sometimes” or more to leakage due to a sudden feeling of needing to rush to urinate were classified as having UUI. Those with both SUI and UUI were classified as MUI. Those participants with UI who did not meet criteria for SUI, UUI, or MUI were classified as Other UI.

A continuous UI severity measure was also calculated using the 7 LUTS Tool UI questions. For each study participant, the weighted Euclidean length (square root of sum of squared responses) was calculated to form a UI severity score (range 1.84–9.44). Questions were weighted by the ratio of the average correlation between a given question and all other questions to the total average correlation so that less weight was given to questions that had high correlation with other questions (e.g., multiple questions assessing SUI)14.

Participants also completed the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA Revised (PISQ-IR)10, Genitourinary Pain Index (GUPI)11, Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 (PFDI-20) 12, and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) GI Constipation, Diarrhea, and Fecal Incontinence scales13. The PFDI-20 is a condition-specific quality of life measure that assesses bother related to pelvic floor symptoms and includes three scales, the Urinary Distress Inventory (UDI-6), Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory (POPDI-6), and Colo-Rectal-Anal Distress Inventory (CRADI-8). Each scale is scored 0–100 with a higher score indicating greater bother. The PISQ-IR measures sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders separately for sexually and not sexually active women. A higher score on the subscale indicates better sexual function. There is no summary score for the PISQ-IR.

PROMIS measures used short forms to derive T-scores normalized to the U.S. population as a reference (by definition, mean=50, standard deviation [SD] = 10). One exception was fecal incontinence, which uses a raw score as the metric. Higher scores on PROMIS measures indicate more symptoms.

Statistical Methods

Characteristics of the participants are shown as means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages. Tests for differences by group were performed using chi-square tests and Wilcoxon two-sample tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Descriptive statistics were calculated for sexual function, pelvic floor, and bowel symptom measures; differences between groups were tested using one-way ANOVA and Cohen’s d was used to calculate effect sizes. Urinary subscales (GUPI urinary subscale and UDI-6 subscale of PFDI-20) and summary scores including urinary subscales were excluded due to similarity to LUTS Tool questions.

Multivariable linear regression was used to test for associations between incontinence status (UI vs. non-UI) and sexual function, pelvic floor, and bowel measures. Candidate covariates included age, race, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), education, employment status, smoking status, diabetes, sleep apnea, functional comorbidity index (FCI), menopausal status (with and without hormone use), history of psychiatric diagnosis, previous brain or spinal surgery, more than two urinary tract infections in the past year by self-report, hysterectomy, any vaginal births, and alcohol consumption. Best subset selection guided covariate selection for all models. Similar models were created to test for associations between the outcomes and UI subtype (SUI, UUI, and MUI, with MUI as the reference category due to its prevalence and increased severity) and UI severity. Data on POP-Q and pelvic floor strength (Oxford scale) were each missing in 20% of participants and were excluded as potential covariates; however, they were tested in separate sub-analyses. All p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (FDR) correction. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Among 545 women recruited from the six sites, 510 with complete responses to the 7 LUTS Tool questions required for UI subtyping were included in the present analyses. Mean age was 56.4 ±14.4 years; most were Caucasian (82%) (Table 1). Mean BMI was 30.6 ±7.8 kg/m 2, and 15% reported a history of diabetes. A median of two vaginal births was reported. Sixty-four percent were post-menopausal and 17% used estrogen treatment (topical or systemic). Sixty-three percent had a stage 0 or 1 pelvic organ prolapse on physical exam, 30% had stage 2, and 6% had stage 3 or 4. At baseline, few study participants reported taking an anti-muscarinic drug (2%) or medication to relieve constipation (6%). Thirty percent had prior hysterectomy, and 14% had undergone surgery for UI and/or prolapse. One-half of the women were sexually active (51%). The mean functional comorbidity index was 2.4 ±2.2 for the group, and mean post-void residual was 44.8 ±58.7 ml.

Table 1.

Demographics and medical history of LURN female cohort

| Total (n=510) | Non-UI (n=90) | UI (n=420) | p-value* | SUI (n=70) | UUI (n=85) | Mixed UI (n=240) | p-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 56.4 (14.4) | 55.8 (17.1) | 56.6 (13.8) | 0.953 | 56.8 (15.8) | 53.0 (13.4) | 57.6 (13.1) | 0.022 |

| Race | 0.448 | 0.178 | ||||||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 5 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | ||

| Asian | 14 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 12 (3%) | 3 (4%) | 4 (6%) | 5 (2%) | ||

| African-American | 59 (12%) | 8 (9%) | 51 (12%) | 14 (16%) | 6 (9%) | 30 (13%) | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| White | 418 (82%) | 74 (82%) | 344 (82%) | 62 (73%) | 59 (84%) | 200 (84%) | ||

| Multi-racial/Other | 12 (2%) | 4 (4%) | 8 (2%) | 4 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (1%) | ||

| Education | 0.159 | 0.204 | ||||||

| < HS Diploma/GED | 11 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 10 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 7 (3%) | ||

| HS Diploma/GED | 45 (9%) | 4 (5%) | 41 (10%) | 6 (7%) | 5 (7%) | 29 (12%) | ||

| Some college/tech school - no degree | 117 (23%) | 17 (20%) | 100 (24%) | 19 (22%) | 10 (14%) | 64 (27%) | ||

| Associate’s degree | 57 (11%) | 7 (8%) | 50 (12%) | 9 (11%) | 11 (16%) | 26 (11%) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 153 (30%) | 29 (34%) | 124 (30%) | 27 (32%) | 21 (30%) | 68 (29%) | ||

| Graduate degree | 119 (24%) | 28 (33%) | 91 (22%) | 23 (27%) | 21 (30%) | 42 (18%) | ||

| Employment | 0.145 | 0.054 | ||||||

| Employed part-time | 72 (14%) | 12 (14%) | 60 (14%) | 14 (16%) | 10 (14%) | 35 (15%) | ||

| Employed full-time | 197 (39%) | 30 (34%) | 167 (40%) | 32 (38%) | 38 (54%) | 81 (34%) | ||

| Unemployed (looking for work) | 14 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (4%) | 10 (4%) | ||

| Not employed (not looking for work) | 221 (44%) | 46 (52%) | 175 (42%) | 38 (45%) | 19 (27%) | 110 (47%) | ||

| BMI | 30.6 (7.8) | 28.2 (5.9) | 31.1 (8.1) | 0.002 | 30.6 (7.9) | 27.9 (6.4) | 32.4 (8.3) | <.001 |

| < 25 | 137 (27%) | 28 (32%) | 109 (26%) | 0.015 | 25 (29%) | 30 (43%) | 47 (20%) | 0.006 |

| 25–30 | 131 (26%) | 31 (36%) | 100 (24%) | 19 (22%) | 17 (24%) | 55 (23%) | ||

| 30–35 | 108 (22%) | 16 (18%) | 92 (22%) | 18 (21%) | 13 (19%) | 60 (26%) | . | |

| >35 | 126 (25%) | 12 (14%) | 114 (27%) | 23 (27%) | 10 (14%) | 73 (31%) | ||

| Current or Former Smoker | 174 (35%) | 22 (26%) | 152 (37%) | 0.050 | 22 (26%) | 23 (33%) | 96 (41%) | 0.040 |

| Diabetes | 74 (15%) | 13 (15%) | 61 (15%) | 0.972 | 12 (14%) | 6 (9%) | 39 (16%) | 0.257 |

| >2 UTIs in the past year | 236 (48%) | 32 (37%) | 204 (50%) | 0.029 | 34 (41%) | 32 (46%) | 128 (55%) | 0.057 |

| Sleep Apnea | 90 (18%) | 10 (11%) | 80 (19%) | 0.087 | 12 (14%) | 4 (6%) | 59 (25%) | <.001 |

| History of psychiatric diagnosis | 218 (43%) | 32 (36%) | 186 (45%) | 0.156 | 33 (39%) | 26 (37%) | 116 (49%) | 0.104 |

| Previous brain or spinal surgery | 37 (7%) | 5 (6%) | 32 (8%) | 0.511 | 6 (7%) | 1 (1%) | 23 (10%) | 0.071 |

| Number of Vaginal Births | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.8 (1.4) | 0.148 | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.5) | 0.606 |

| Post-menopausal | 323 (64%) | 52 (59%) | 271 (66%) | 0.245 | 59 (69%) | 39 (56%) | 155 (66%) | 0.170 |

| Hormone Use | 55 (17%) | 11 (21%) | 44 (16%) | 0.430 | 8 (14%) | 12 (32%) | 23 (15%) | 0.034 |

| Anticholinergic medication use | 11 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 8 (2%) | 0.397 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (2%) | 0.838 |

| Anti-Constipation medication use | 32 (6%) | 8 (9%) | 24 (6%) | 0.260 | 5 (6%) | 4 (6%) | 13 (5%) | 0.985 |

| Previous Surgeries (multiple possible) | ||||||||

| Urgency incontinence | 6 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (1%) | 0.254 | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 3 (1%) | 0.600 |

| SUI/Prolapse | 66 (13%) | 10 (11%) | 56 (13%) | 0.569 | 11 (13%) | 3 (4%) | 38 (16%) | 0.042 |

| Hysterectomy | 154 (30%) | 23 (26%) | 131 (31%) | 0.328 | 27 (32%) | 21 (30%) | 76 (32%) | 0.948 |

| Urethral Dilation | 3 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) | 0.421 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 0.523 |

| Other | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.643 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.723 |

| Functional Comorbidity Index | 2.4 (2.2) | 1.9 (1.8) | 2.5 (2.2) | 0.012 | 2.2 (2.0) | 1.9 (1.8) | 2.8 (2.3) | 0.002 |

| Prolapse | <.001 | 0.397 | ||||||

| Stage 0 | 134 (31%) | 34 (44%) | 100 (28%) | 25 (34%) | 16 (27%) | 50 (25%) | ||

| Stage 1 | 140 (32%) | 17 (22%) | 123 (35%) | 27 (37%) | 22 (37%) | 69 (34%) | ||

| Stage 2 | 131 (30%) | 15 (19%) | 116 (33%) | 20 (27%) | 17 (28%) | 74 (37%) | ||

| Stage 3 | 26 (6%) | 11 (14%) | 15 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (8%) | 8 (4%) | ||

| Stage 4 | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | . | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | |

| Anterior vaginal wall (Aa, cm) | −1.7 (1.3) | −1.7 (1.5) | −1.7 (1.3) | 0.520 | −1.8 (1.3) | −1.7 (1.2) | −1.6 (1.3) | 0.448 |

| Posterior vaginal wall (Ba, cm) | −1.6 (1.9) | −1.4 (2.3) | −1.7 (1.8) | 0.764 | −1.8 (1.3) | −1.3 (1.5) | −1.7 (2.0) | 0.214 |

| Pelvic Floor Muscle Strength (Oxford Scale) | 0.501 | 0.082 | ||||||

| Grade 0 | 39 (11%) | 6 (9%) | 33 (11%) | 8 (13%) | 4 (8%) | 18 (11%) | ||

| Grade 1 | 81 (22%) | 15 (22%) | 66 (22%) | 15 (25%) | 12 (23%) | 36 (21%) | ||

| Grade 2 | 84 (23%) | 13 (19%) | 71 (24%) | 13 (21%) | 8 (15%) | 47 (28%) | ||

| Grade 2 | 80 (22%) | 16 (23%) | 64 (21%) | 10 (16%) | 12 (23%) | 38 (22%) | ||

| Grade 4 | 61 (17%) | 11 (16%) | 50 (17%) | 8 (13%) | 13 (25%) | 27 (16%) | ||

| Grade 5 | 24 (7%) | 8 (12%) | 16 (5%) | 7 (11%) | 4 (8%) | 3 (2%) | ||

| PVR (ml) | 44.8 (58.7) | 53.3 (68.4) | 42.9 (56.2) | 0.319 | 46.2 (63.8) | 31.0 (56.1) | 43.3 (52.7) | 0.064 |

| Alcoholic Beverages Consumed Per Week | 0.624 | 0.580 | ||||||

| 0–3 | 334 (68%) | 62 (74%) | 272 (66%) | 58 (69%) | 47 (67%) | 150 (65%) | ||

| 4–7 | 60 (12%) | 8 (10%) | 52 (13%) | 12 (14%) | 11 (16%) | 24 (10%) | ||

| 8–14 | 14 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 12 (3%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 7 (3%) | ||

| >14 | 3 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | ||

| Never consumed alcohol | 83 (17%) | 11 (13%) | 72 (18%) | 10 (12%) | 10 (14%) | 49 (21%) |

P-value for wet vs. dry from chi-square test or Wilcoxon 2-sample test

P-value for SUI vs. UUI vs. Mixed UI from chi-square test or Kruskal-Wallis test

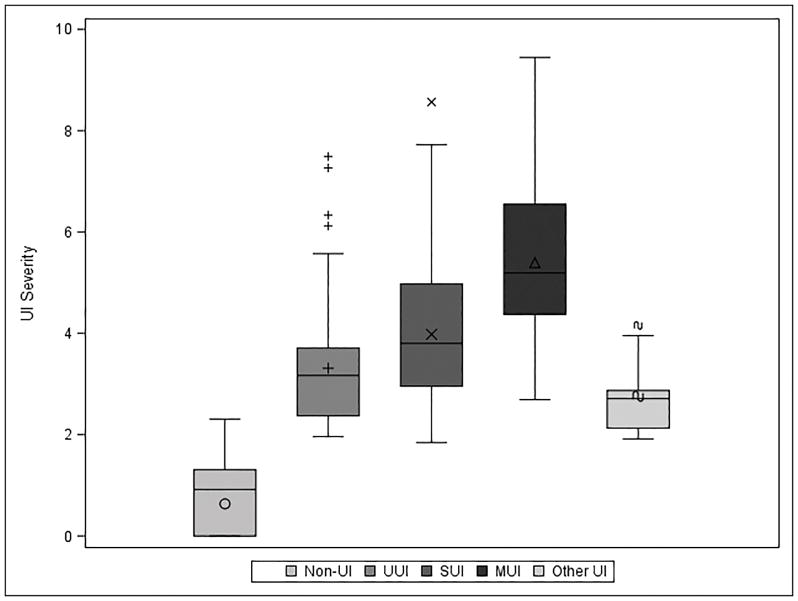

Overall, 90 (18%) women reported no more than rarely having incontinence on any of the seven incontinence questions (16a-g) on the LUTS tool and were considered “without UI.” Compared to the 420 women with UI, those without UI had lower mean BMI (28.2 vs. 31.1, p=0.002), were less likely to have recurrent urinary tract infections in the prior year (37% vs. 50%, p=0.029), and had fewer self-reported comorbidities (FCI 1.9 vs. 2.5, p=0.012). Of the 420 women with UI, most had MUI (57%), 20% had UUI, and 17% SUI. Six percent (n=25) had Other UI. Women reporting MUI were older, with higher BMI, higher prevalence of smoking and sleep apnea, and more comorbidities compared to women with UUI or SUI only. Women with MUI had significantly higher UI severity compared to women with SUI or UUI (Figure 1). Average UI severity in the MUI group was 5.39±1.54 compared to 3.98±1.48 (SUI) and 3.31±1.13 (UUI) (all p<0.001).

Figure 1.

UI Severity by subtype. UI severity was calculated as the weighted Euclidean distance (square root of sum of squared responses) of 7 LUTS Tool incontinence questions. Weights were calculated using the ratio of average correlation of a given question to the average total correlation of all 7 questions in order to account for potential redundancy in questions.

Associations between sexual functioning and UI

In terms of sexual dysfunction, only a few of the PISQ subscales were significantly different between groups. Among sexually active women only, the PISQ-SA Condition Impact and Condition Specific subscales were lower (worse function) in women with UI (mean scores 79.8 [UI] vs. 92.5 [non-UI], p<0.001 and 89.8 [UI] vs. 96.7 [non-UI], p=0<0.001) compared to women without UI, and these differences remained significant after adjusting for BMI, smoking status, and parity.

Among women with UI who reported they were sexually active, those with MUI reported lower mean scores on PISQ SA-Condition Impact subscale (worse function) (average 73.3) compared to women with SUI (average 86.3) and women with UUI (average 87.4). These differences remained significant after covariate adjustment (Supplemental Table 1). Urinary incontinence occurring during sexual intercourse was more common in the SUI and MUI groups, with 17% and 18%, respectively, compared to only 4% in the UUI group (p=0.004). Women who reported more severe UI, regardless of subtype, had significantly worse sexual function on the PISQ SA-Condition Specific (on average 3.05 point reduction in PISQ score per unit increase in UI severity, p<0.001) and Condition Impact measures (on average 2.64 point reduction in PISQ score per unit increase in UI severity, p=0.01).

Associations between prolapse symptoms and UI

Bother associated with prolapse was marginally higher in women with UI (average POPDI-6 scores 17.1 vs. 13.8, p=0.10, Table 2), although measures of anterior and posterior vaginal wall descent did not differ between the two groups. Among those with UI, women with MUI reported more bother associated with prolapse (average POPDI-6 scores 20.6 compared to 10.7 [UUI] and 12.4 [SUI], p<0.001, Table 3), and these differences remained statistically significant after adjustment. In all women, as UI severity increased, women reported worse pelvic floor distress on the POPDI-6.

Table 2.

Pelvic Floor Measures among Women with and without Urinary Incontinence

| Indices | N Non-UI | Mean (SD) Non-UI | N UI | Mean (SD) UI | p-value* | Adjusted p-value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PISQ NSA-Condition Specific | 29 | 21.9 (21.3) | 187 | 29.1 (30.0) | 0.168 | |

| PISQ NSA-Partner Related | 31 | 60.7 (26.7) | 192 | 59.8 (29.7) | 0.912 | |

| PISQ NSA-Global Quality | 29 | 38.1 (32.8) | 188 | 48.4 (33.1) | 0.168 | |

| PISQ NSA-Condition Impact | 30 | 12.2 (22.3) | 188 | 24.0 (31.7) | 0.031 | 0.11 |

| PISQ SA-Arousal Orgasm | 50 | 66.4 (19.0) | 198 | 61.8 (19.7) | 0.189 | |

| PISQ SA-Partner Related | 48 | 75.8 (24.6) | 184 | 78.4 (24.5) | 0.596 | |

| PISQ SA-Condition Specific | 49 | 96.7 (8.9) | 195 | 89.8 (15.8) | <.001 | 0.05 |

| PISQ SA-Global Quality | 49 | 62.9 (26.9) | 197 | 62.6 (30.4) | 0.961 | |

| PISQ SA-Condition Impact | 49 | 92.5 (14.8) | 198 | 79.8 (28.0) | <.001 | 0.01 |

| PISQ SA-Desire | 50 | 55.5 (21.9) | 197 | 54.1 (21.9) | 0.767 | |

| GUPI Pain Subscale | 65 | 4.1 (4.2) | 300 | 4.7 (5.1) | 0.461 | |

| PFDI POPDI6 | 87 | 13.8 (14.2) | 406 | 17.1 (20.0) | 0.104 | |

| PFDI CRADI8 | 87 | 14.8 (18.2) | 404 | 21.0 (20.4) | 0.022 | 0.15 |

| PROMIS GI Constipation T-score | 86 | 48.4 (8.8) | 404 | 51.9 (8.9) | 0.003 | 0.02 |

| PROMIS GI Diarrhea T-score | 88 | 46.2 (8.6) | 410 | 49.5 (9.6) | 0.008 | 0.02 |

| PROMIS GI Bowel Incontinence Raw Score | 87 | 4.8 (2.2) | 389 | 5.4 (2.5) | 0.058 |

P-value from t-test.

P-value from multivariable linear regression models. Models were built using best subset selection with potential adjustment variables listed in Table 1. Full model results can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

PISQ=Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire; NSA = Not Sexually Active; SA = Sexually Active; GUPI = Genitourinary Pain Index; PFDI = Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory; POPDI = Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory; CRADI = Colo-rectal-anal Distress Inventory; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; GI=Gastrointestinal

Table 3.

Pelvic Floor Measures among Women by Urinary Incontinence Subtype

| UUI | SUI | Mixed UI | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Indices | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | Overall ANOVA p-value* | SUI vs. Mixed p-value* | UUI vs. Mixed p-value* | Adjusted Overall p-value** | Adjusted SUI vs. Mixed p-value** | Adjusted UUI vs. Mixed p-value** |

| PISQ NSA-Condition Specific | 40 | 22.0 (30.3) | 20 | 28.5 (23.8) | 115 | 31.4 (30.2) | 0.270 | 0.715 | 0.129 | |||

| PISQ NSA-Partner Related | 42 | 69.4 (29.0) | 20 | 43.3 (21.3) | 118 | 58.8 (29.5) | 0.010 | 0.049 | 0.074 | 0.004 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| PISQ NSA-Global Quality | 40 | 40.4 (32.4) | 20 | 59.1 (37.5) | 116 | 49.5 (32.1) | 0.143 | 0.271 | 0.172 | |||

| PISQ NSA-Condition Impact | 41 | 18.7 (30.2) | 20 | 25.6 (31.9) | 115 | 26.5 (32.3) | 0.434 | 0.901 | 0.221 | |||

| PISQ SA-Arousal Orgasm | 41 | 65.0 (18.8) | 46 | 66.9 (16.2) | 98 | 57.7 (21.3) | 0.034 | 0.021 | 0.082 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| PISQ SA-Partner Related | 37 | 79.7 (27.8) | 44 | 84.7 (18.3) | 92 | 74.1 (26.2) | 0.099 | 0.042 | 0.288 | |||

| PISQ SA-Condition Specific | 41 | 93.2 (14.4) | 45 | 91.3 (12.4) | 96 | 87.1 (18.1) | 0.136 | 0.198 | 0.078 | |||

| PISQ SA-Global Quality | 41 | 65.8 (31.8) | 45 | 68.2 (24.8) | 98 | 57.9 (32.4) | 0.169 | 0.099 | 0.213 | |||

| PISQ SA-Condition Impact | 42 | 87.4 (24.4) | 45 | 86.3 (22.6) | 98 | 73.3 (29.9) | 0.010 | 0.019 | 0.013 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| PISQ SA-Desire | 41 | 56.1 (23.9) | 45 | 52.9 (20.0) | 98 | 53.8 (22.8) | 0.811 | 0.836 | 0.616 | |||

| GUPI Pain Subscale | 57 | 4.0 (4.6) | 55 | 4.2 (4.7) | 170 | 5.0 (5.4) | 0.388 | 0.346 | 0.258 | |||

| PFDI POPDI6 | 84 | 10.7 (14.7) | 68 | 12.4 (15.0) | 229 | 20.6 (22.4) | <.001 | 0.008 | <.001 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.004 |

| PFDI CRADI8 | 84 | 18.3 (19.0) | 68 | 12.8 (13.7) | 227 | 24.3 (21.4) | <.001 | <.001 | 0.036 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.20 |

| PROMIS GI Constipation T-score | 85 | 50.9 (8.3) | 66 | 50.3 (8.6) | 229 | 52.6 (9.0) | 0.139 | 0.099 | 0.169 | |||

| PROMIS GI Diarrhea T-score | 85 | 47.9 (9.1) | 68 | 46.0 (8.7) | 232 | 51.3 (9.8) | <.001 | <.001 | 0.013 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| PROMIS GI Bowel Incontinence Raw Score | 82 | 5.2 (2.3) | 63 | 4.5 (1.2) | 220 | 5.8 (2.9) | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.099 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.10 |

P-values from one-way ANOVA with pairwise p-values for SUI vs. Mixed and UUI vs. Mixed.

P-values from multivariable linear regression models (overall and pairwise for SUI vs. Mixed and UUI vs. Mixed). Models were build using best subset selection with potential adjustment variables listed in Table 1. Full model results can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

PISQ=Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire; NSA = Not Sexually Active; SA = Sexually Active; GUPI = Genitourinary Pain Index; PFDI = Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory; POPDI = Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory; CRADI = Colo-rectal-anal Distress Inventory; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; GI=Gastrointestinal

Associations between bowel function and UI

Compared to those without UI, women with UI had higher PROMIS Constipation (51.9 vs. 48.4, p=0.003), and Diarrhea scores (49.5 vs. 46.2, p=0.008), indicating worse bowel function (Table 2). On multivariable linear regression of these bowel function measures adjusted for other statistically significant covariates (Supplementary Table 2), these results were only minimally changed. CRADI-8 scores were also higher for women with UI (21.0 vs. 14.8, p=0.02), but this difference did not remain statistically significant after adjustment for comorbidities and parity.

Among those with UI, the MUI group experienced more bowel symptoms and had higher (worse) PROMIS scores for diarrhea and fecal incontinence (Table 1). There were no significant differences in PROMIS Constipation scores among the various UI subtypes with MUI as the reference category. CRADI-8 scores were also higher (more bother) among the MUI group compared with SUI and UUI groups. After adjustment, the differences remained between the MUI and SUI groups, but not between MUI and UUI. As UI severity increased, bowel function worsened on all three PROMIS bowel measures; CRADI-8 scores measuring bother related to bowel function also increased. Full models are available in Supplemental Table 3.

Discussion

We report the relationships between UI and other pelvic floor symptoms and quality of life measures, including bowel, prolapse, and sexual function, in over 500 women seeking care for LUTS. Overall, our results show that in women with LUTS: (1) the presence of UI is associated with constipation and poor sexual function; (2) MUI is associated with worse fecal incontinence, diarrhea, pelvic organ prolapse symptoms, and sexual function compared to SUI; and (3) more severe UI symptoms, regardless of UI subtype, are associated with worse bowel function (fecal incontinence, diarrhea, constipation), pelvic organ prolapse symptoms, and sexual function.

Although it is well known that UI adversely affects sexual function in women, less is known about the effects of UI subtypes. Conflicting results were reported in three studies, which identified UI subtypes by urodynamic testing and assessed sexual function (in sexually active women) through PISQ-12 scores6,7,15. Two of these studies found SUI patients had worse sexual function than UUI patients6,7, and one found MUI patients had the poorest sexual function7. The third study found no difference in sexual function between all three UI subtypes 16. All of these studies were limited by small sample sizes and their results were not adjusted for potentially important covariates, such as age, BMI, and comorbidities. In contrast to these prior results, we found poorer sexual function in women with MUI among sexually active women, but no large differences in function between stress and urgency UI subtypes using a much larger sample of women and multivariable analysis.

The association between pelvic organ prolapse and UI has pathophysiological basis. SUI commonly occurs with pelvic organ prolapse, due to similar pelvic floor injury causing urethral hypermobility and/or some degree of intrinsic sphincter deficiency. UUI may also have a strong relationship to pelvic organ prolapse17 since POP may cause bladder outlet obstruction and overactive bladder symptoms. A large cystocele may also put traction on the urethra, resulting in an open urethra. Surgical repair of pelvic organ prolapse has been shown to improve UUI in the majority of patients3. Levator ani pelvic floor muscle injury, sphincteric injury, and/or pudendal nerve injury may be also present in a subset of patients who have concomitant UI, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence2,18,19. Thus, our finding that increasing UI severity was associated with more distress from prolapse symptoms was not surprising.

Regarding bowel function, past studies have similarly demonstrated that constipation, difficult defecation, and fecal incontinence occur commonly in women with LUTS20–22. Studies performed in specialty clinic populations have demonstrated associations between functional constipation and overactive bladder22, and a high prevalence (19%) of fecal incontinence in women seeking care for urinary incontinence20. However, there have only been a few studies that have examined the effects of UI subtypes on bowel dysfunction. Meschia et al. suggested that anal incontinence is more prevalent among patients with MUI and UUI than SUI (28.8%, 28.7%, and 21.8%, respectively)23. We have also demonstrated increased bowel dysfunction (fecal incontinence and diarrhea) in women with mixed UI, compared to SUI. Our results strengthen these prior findings with the use of validated PROMIS questionnaires (rather than a non-validated screening questionnaire) to assess the bowel symptoms and multivariable analysis to adjust for potential confounding variables.

There are several theoretical explanations for the association between bowel and bladder dysfunction. Both the bladder and bowel originate embryologically from the same cloaca and, given the proximity of the bowel and bladder in the pelvis, a distended rectal vault could have a mass effect on the bladder. Both the distal bowel and bladder share afferent nerves, as well, explaining why sacral neuromodulation is used to treat both bowel and bladder incontinence. Studies on the treatments of one organ resulting in a positive impact on other pelvic organs are lacking in adults. However, it has been clearly demonstrated that aggressive treatment of constipation in children with dysfunctional elimination without any bladder intervention frequently results in resolution of UI12. These theories may explain why women with MUI have worse bowel function since they likely have combined anatomic (loss of support) and neurologic deficits.

Our study has several important strengths. First, we used a condition-specific questionnaire (PISQ-12) to assess sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders. The questionnaire has undergone validation in this patient population and assesses both sexually active and non-active women10. Second, bowel symptoms were assessed using validated PROMIS questionnaires13. Finally, unlike many previous studies that were typically from a single center with small sample size, we have recruited a large number of women prospectively across several sites; this may enhance the generalizability of our findings to other care-seeking women in different clinical care settings.

Our study has several limitations. As it entails cross-sectional comparisons, the causal relationship of one symptom to another cannot be inferred. The classification into SUI, UUI, and MUI was based on self-reported symptoms on the LUTS Tool questionnaire, and not urodynamic findings. Also, patients were recruited at tertiary academic centers with expertise in managing LUTS. Thus, our results may be less generalizable to women who seek treatment with community urologists, gynecologists, or primary care physicians. On the other hand, relatively few women reported taking anticholinergic medications (2%) or had had prior pelvic surgery for UI at study entry (14%), suggesting our participants did not include many complex or refractory cases. Finally, the UI severity measure reported here has not been validated and therefore results regarding UI severity may not be reproducible in other populations.

Conclusion

Among women seeking care for LUTS, those with UI symptoms, mixed UI, and/or more severe UI were more likely to report poorer bowel dysfunction, prolapse symptoms, and worse sexual function. Our findings suggest that health care providers should question their patients seeking care for LUTS to identify and manage co-occurring pelvic floor dysfunctions.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1: Multivariable Linear Regression Models of Pelvic Floor Measures – Urinary Incontinence Subtype

Supplementary Table 2: Multivariable Linear Regression Models of Pelvic Floor Measures

Supplementary Table 3: Multivariable Linear Regression Models of Pelvic Floor Measures – Urinary Incontinence Severity

Acknowledgments

Funding

This is publication number 7 of the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN).

This study is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases through cooperative agreements (grants DK097780, DK097772, DK097779, DK099932, DK100011, DK100017, DK097776, DK099879).

Research reported in this publication was supported at Northwestern University, in part, by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant Number UL1TR001422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The following individuals were instrumental in the planning and conduct of this study at each of the participating institutions:

Duke University, Durham, North Carolina (DK097780): PI: Cindy Amundsen, MD, Kevin Weinfurt, PhD; Co-Is: Kathryn Flynn, PhD, Matthew O. Fraser, PhD, Todd Harshbarger, PhD, Eric Jelovsek, MD, Aaron Lentz, MD, Drew Peterson, MD, Nazema Siddiqui, MD, Alison Weidner, MD; Study Coordinators: Carrie Dombeck, MA, Robin Gilliam, MSW, Akira Hayes, Shantae McLean, MPH

University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA (DK097772): PI: Karl Kreder, MD, MBA, Catherine S Bradley, MD, MSCE, Co-Is: Bradley A. Erickson, MD, MS, Susan K. Lutgendorf, PhD, Vince Magnotta, PhD, Michael A. O’Donnell, MD, Vivian Sung, MD; Study Coordinator: Ahmad Alzubaidi

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL (DK097779): PIs: David Cella, Brian Helfand, MD, PhD; Co-Is: James W Griffith, PhD, Kimberly Kenton, MD, MS, Christina Lewicky-Gaupp, MD, Todd Parrish, PhD, Jennie Yufen Chen, PhD, Margaret Mueller, MD; Study Coordinators: Sarah Buono, Maria Corona, Beatriz Menendez, Alexis Siurek, Meera Tavathia, Veronica Venezuela, Azra Muftic, Pooja Talaty, Jasmine Nero. Dr. Helfand, Ms. Talaty, and Ms. Nero are at NorthShore University HealthSystem.

University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, MI (DK099932): PI: J Quentin Clemens, MD, FACS, MSCI; Co-Is: Mitch Berger, MD, PhD, John DeLancey, MD, Dee Fenner, MD, Rick Harris, MD, Steve Harte, PhD, Anne P. Cameron, MD, John Wei, MD; Study Coordinators: Morgen Barroso, Linda Drnek, Greg Mowatt, Julie Tumbarello

University of Washington, Seattle Washington (DK100011): PI: Claire Yang, MD; Co-I: John L. Gore, MD, MS; Study Coordinators: Alice Liu, MPH, Brenda Vicars, RN

Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis Missouri (DK100017): PI: Gerald L. Andriole, MD, H. Henry Lai; Co-I: Joshua Shimony, MD, PhD; Study Coordinators: Susan Mueller, RN, BSN, Heather Wilson, LPN, Deborah Ksiazek, BS, Aleksandra Klim, RN, MHS, CCRC National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division of Kidney, Urology, and Hematology, Bethesda, MD: Project Scientist: Ziya Kirkali MD; Project Officer: John Kusek, PhD; NIH Personnel: Tamara Bavendam, MD, Robert Star, MD, Jenna Norton

Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, Data Coordinating Center (DK097776 and DK099879): PI: Robert Merion, MD, FACS; Co-Is: Victor Andreev, PhD, DSc, Brenda Gillespie, PhD, Gang Liu, PhD, Abigail Smith, PhD; Project Manager: Melissa Fava, MPA, PMP; Clinical Study Process Manager: Peg Hill-Callahan, BS, LSW; Clinical Monitor: Timothy Buck, BS, CCRP; Research Analysts: Margaret Helmuth, MA, Jon Wiseman, MS; Project Associate: Julieanne Lock, MLitt

Footnotes

Disclosures: See separately uploaded forms.

References

- 1.Ng S, YC C, Lin L, GD C. Anorectal dysfunction in women with urinary incontinence or lower tract symptoms. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2002;77:139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheer I, Andrews V, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Urinary incontinence after obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) - Is there a relationship? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(2):179–183. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0431-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim MS, Lee GH, Na ED, Jang JH, Kim HC. The association of pelvic organ prolapse severity and improvement in overactive bladder symptoms after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obs Gynecol Sci. 2016;59(3):214–219. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2016.59.3.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei JT, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al. A midurethral sling to reduce incontinence after vaginal prolapse repair. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(25):2358–2367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karbage SAL, Santos ZMSA, Frota MA, et al. Quality of life of Brazilian women with urinary incontinence and the impact on their sexual function. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;201:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Cam C, Cogendez E, Karateke A. Effects of urinary incontinence subtypes on women’s quality of life (including sexual life) and psychosocial state. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;176(1):187–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coksuer H, Ercan CM, Halilolu B, et al. Does urinary incontinence subtypes affect sexual function? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;159(1):213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cameron AP, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Smith AR, et al. Baseline Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Patients Enrolled in the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN): a Prospective, Observational Cohort Study. J Urol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coyne KS, Barsdorf AI, Thompson C, et al. Moving towards a comprehensive assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31(4):448–454. doi: 10.1002/nau.21202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers RG, Coates KW, Kammerer-Doak D, Khalsa S, Qualls C. A short form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12) Int Urogynecol J. 2003;14(3):164–168. doi: 10.1007/s00192-003-1063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clemens JQ, Calhoun EA, Litwin MS, et al. Validation of a Modified National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index to Assess Genitourinary Pain in Both Men and Women. Urology. 2009;74(5) doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barber MD, Chen Z, Lukacz E, et al. Further validation of the short form versions of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(4):541–546. doi: 10.1002/nau.20934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spiegel BMR, Hays RD, Bolus R, et al. Development of the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Gastrointestinal Symptom Scales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(11):1804–1814. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helmuth M, Smith A, Andreev V, et al. Use of Euclidean Length to Measure Urinary Incontinence Severity Based on the Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Tool. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.219. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urwitz-Lane R, Ozel B. Sexual function in women with urodynamic stress incontinence, detrusor overactivity, and mixed urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(6):1758–1761. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Urwitz-Lane R, Ozel B. Sexual function in women with urodynamic stress incontinence, detrusor overactivity, and mixed urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(6):1758–1761. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Boer TA, Salvatore S, Cardozo L, et al. Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Overactive Bladder. Neurourol Urodynamics Neurourol Urodynam. 2010;29(29):30–3930. doi: 10.1002/nau.20858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SLJ, AMW, TLH, ARM, MDW Fecal incontinence in women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(3):423–427. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00499-1%5Cnhttp://sfxhosted.exlibrisgroup.com/medtronic?sid=EMBASE&issn=00297844&id=doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00499-1&atitle=Feca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heilbrun ME, Nygaard IE, Lockhart ME, et al. Correlation between levator ani muscle injuries on magnetic resonance imaging and fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and urinary incontinence in primiparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(5):488–488.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Paraiso MFR, Walters MD. Functional bowel and anorectal disorders in patients with pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(6):2105–2111. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameron A, Fenner DE, DeLancey JOL, Morgan DM. Self-report of difficult defecation is associated with overactive bladder symptoms. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(7):1290–1294. doi: 10.1002/nau. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maeda T, Tomita M, Nakazawa A, et al. Female Functional Constipation Is Associated with Overactive Bladder Symptoms and Urinary Incontinence. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2017/2138073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meschia M, Buonaguidi A, Pifarotti P, Somigliana E, Spennacchio M, Amicarelli F. Prevalence of anal incontinence in women with symptoms of urinary incontinence and genital prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(4):719–723. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franco I. Overactive Bladder in Children. Part 1: Pathophysiology. J Urol. 2007;178(3):761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: Multivariable Linear Regression Models of Pelvic Floor Measures – Urinary Incontinence Subtype

Supplementary Table 2: Multivariable Linear Regression Models of Pelvic Floor Measures

Supplementary Table 3: Multivariable Linear Regression Models of Pelvic Floor Measures – Urinary Incontinence Severity