Abstract

The expression of chemokine receptor CX3CR1 is related to migration and signaling in cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage. The precise roles of CX3CR1 in the liver have been investigated but not clearly elucidated. Here, we investigated the roles of CX3CR1 in hepatic macrophages and liver injury. Hepatic and splenic CX3CR1lowF4/80low monocytes and CX3CR1lowCD16− monocytes were differentiated into CX3CR1highF4/80high or CX3CR1highCD16+ macrophages by co-culture with endothelial cells. Moreover, CX3CL1 deficiency in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) attenuated the expression of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), whereas recombinant CX3CL1 treatment reversed this expression in co-cultured monocytes. Upon treatment with clodronate liposome, hepatic F4/80high macrophages were successfully depleted at day 2 and recovered similarly in CX3CR1+/GFP and CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice at week 4, suggesting a CX3CR1-independent replacement. However, F4/80high macrophages of CX3CR1+/GFP showed a stronger pro-inflammatory phenotype than CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice. In clodronate-treated chimeric CX3CR1+/GFP and CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice, CX3CR1+F4/80high macrophages showed higher expression of IL-1β and TNF-α than CX3CR1−F4/80high macrophages. In alcoholic liver injury, despite the similar frequency of hepatic F4/80high macrophages, CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice showed reduced liver injury, hepatic fat accumulation, and inflammatory responses than CX3CR1+/GFP mice. Thus, CX3CR1 could be a novel therapeutic target for pro-inflammatory macrophage-mediated liver injury.

Introduction

The liver is considered an immunological organ because of the allocation of diverse types of innate and adaptive immune cells1. Kupffer cells are resident macrophages that are tightly attached along the liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs). Kupffer cells are characterized by the differential expression of specific markers (e.g. F4/80highCD11b+ or Ly6ClowCD11b+ in mice but CD14+CD16+ in humans) compared to circulating F4/80lowCD11b+ mouse and CD14highCD16− human monocytes, and they participate in the pathogenesis of a broad spectrum of liver diseases and insulin resistance via switching of the alternative M2 phenotype to the classical M1 phenotype by various damage- and pathogen-associated molecular patterns2,3. The origin of Kupffer cells has been intensively studied but remains undefined. Fate-mapping recently revealed that several tissue-specific macrophages originate from either the yolk sac or fetal hematopoietic stem cells and proliferate locally4–6. Other findings indicate that Kupffer cells might originate from the bone marrow or intrahepatic precursor cells as a result of local proliferation5,7–9. However, the factors that regulate the differentiation of Kupffer cells from monocytes remain unknown.

Chemokines and their receptors play important roles in attracting circulating monocytes to inflamed liver tissues. CCR2-dependent migration of Ly6C+ monocytes in mice and CD14+ monocytes in humans constitute the predominant pro-inflammatory macrophages10–12. However, differential Ly6C expression in CCR2+ monocytes such as Ly6Chigh monocytes (analogous to classical CD14highCD16− human monocytes) and Ly6Clow monocytes (analogous to non-classical CD14lowCD16+ human monocytes), play opposite (pro-inflammatory versus restorative) or dual roles in liver inflammation and fibrosis in mice and humans, or often simultaneously express M1 and M2 markers12,13. Circulating pro-inflammatory CCR2highCX3CR1low monocytes differentiate into restorative CX3CR1highCCR2low macrophages at sites of sterile liver injury. Ly6ChighCX3CR1low monocytes transform to CX3CR1highLy6Clow macrophages that crawl along endothelial cells to dispose of their cellular debris. Both findings indicate protective functions of CX3CR1high monocytes11,14. However, the mechanisms by which CX3CR1 expression is up-regulated in these conditions and its role have not been investigated.

CX3CR1 is a chemokine receptor of fractalkine (CX3CL1) that is expressed on various cells of the macrophage lineage5,15. CX3CR1 is also involved in the colonization of pre-macrophages at the embryonic stage, leading to differentiation of tissue-resident macrophages, including Kupffer cells15. However, CX3CR1 expression is absent in adult Kupffer cells5. Functionally, CX3CL1-CX3CR1 interaction is important for the migration of immune cells, blood monocyte homeostasis, and for cellular signaling processes that include stimulation of insulin secretion from β-cells16–18. Additionally, CX3CR1 deficiency aggravates liver inflammation and fibrosis by up-regulating the expressions of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and increasing the infiltration of inflammatory monocytes19,20. However, the role of CX3CR1 in alcoholic liver disease has not been studied.

Interestingly, CX3CL1 is synthesized from various types of liver cells, which include hepatocytes, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), and LSECs in chronic liver diseases of humans and mice20–22. In endothelial cells, CX3CL1 expression is up-regulated mainly by cytokine stimulation and is reportedly induced by changes in shear stress23. CX3CR1-expressing monocytes do not dislodge once bound to CX3CL124, supporting the settlement theory of Kupffer cells. However, whether CX3CR1 is involved in differentiation of circulating monocytes into resident-like macrophages in the liver remains unclear.

In the present study, we investigated the role of CX3CR1 in the functional and phenotypic polarization of hepatic macrophages from circulating monocytes using an in vitro differentiation model and an in vivo alcoholic liver disease model.

Results

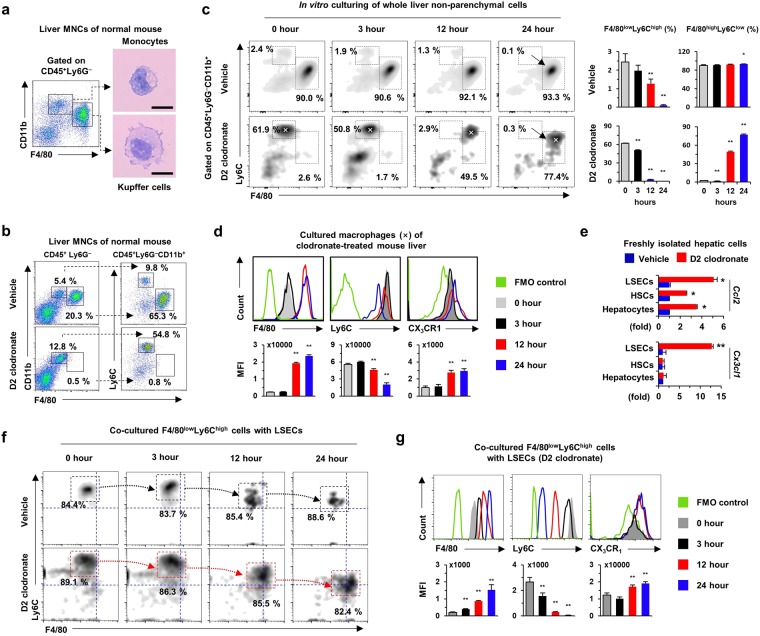

Hepatic endothelial cells regulate the expression of F4/80 and CX3CR1 in hepatic monocytes

Circulating F4/80lowCD11b+ monocytes had bean-shaped nuclei and scant cytoplasm, whereas resident F4/80highCD11b+ Kupffer cells displayed abundant cytoplasm with deviated nuclei in healthy mouse livers (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). After Kupffer cell depletion by clodronate treatment, the circulating monocytes were further characterized by high levels of Ly6C (F4/80lowCD11b+Ly6Chigh), unlike those in F4/80highCD11b+Ly6Clow Kupffer cells (Fig. 1b). To identify the characteristics of these cells in vitro, non-parenchymal cells were isolated from livers of mice with and without 2-day clodronate liposome treatment (D2 clodronate) and the cells were cultured in vitro for 24 h. Similar to in vivo results, unique populations of monocytes and Kupffer cells were identified at 0 h, whereas frequencies of F4/80lowLy6Chigh monocytes in vehicle-treated mice gradually decreased and were absent at 24 h (Fig. 1c). More interestingly, in vitro culturing transformed the phenotype of F4/80lowLy6Chigh monocytes into F4/80highLy6Clow Kupffer-like cells in D2 clodronate-treated mice (Fig. 1c). A histogram analysis showed that Ly6C expression decreased, but the expression of F4/80 and CX3CR1 gradually increased in F4/80lowLy6Chigh monocytes (Fig. 1d). Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses showed that clodronate treatment significantly increased the expression of CX3CL1 only in LSECs, in contrast to increased expression of CCL2 in hepatocytes, HSCs, and LSECs (Fig. 1e), suggesting possible interaction between F4/80lowLy6Chigh monocytes and CX3CL1+ LSECs. To confirm this suggestion, F4/80lowLy6Chigh monocytes were co-incubated with LSECs obtained from D2 clodronate-treated mouse liver. After co-culturing, F4/80lowLy6Chigh monocytes (85.7 ± 2.3%) had markedly differentiated into F4/80highLy6Clow macrophages by LSECs from clodronate-treated mice compared to LSECs from vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 1f). Along with the altered expression of F4/80 and Ly6C, CX3CR1 expression was significantly increased by co-culture with CX3CL1+ LSECs (Fig. 1g). These findings suggested that LSECs with CX3CL1 expression could promote the differentiation of F4/80lowLy6Chigh monocytes into CX3CR1highF4/80highLy6Clow macrophages.

Figure 1.

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) differentiate F4/80lowLy6ChighCX3CR1low monocytes into F4/80highLy6ClowCX3CR1high Kupffer-like macrophages. (a) Isolated mononuclear cells (MNCs) were subjected to flow cytometry. Monocytes and Kupffer cells were subjected to Giemsa staining. Bar = 10 μm. (b) Kupffer cells were depleted by clodronate liposome treatment for 2 days (D2 clodronate). (c,d) Untreated whole liver non-parenchymal cells or cells treated with D2 clodronate were cultured in vitro for 24 h and analyzed by flow cytometry. (e) Gene expression was analyzed in isolated LSECs, hepatic stellate cells, and hepatocytes. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to corresponding control. (f,g) Isolated F4/80lowLy6Chigh monocytes were co-cultured with LSECs of vehicle or D2 clodronate-treated mice for 24 h and they were subjected to flow cytometry. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to 0 h. The results represent three independent experiments.

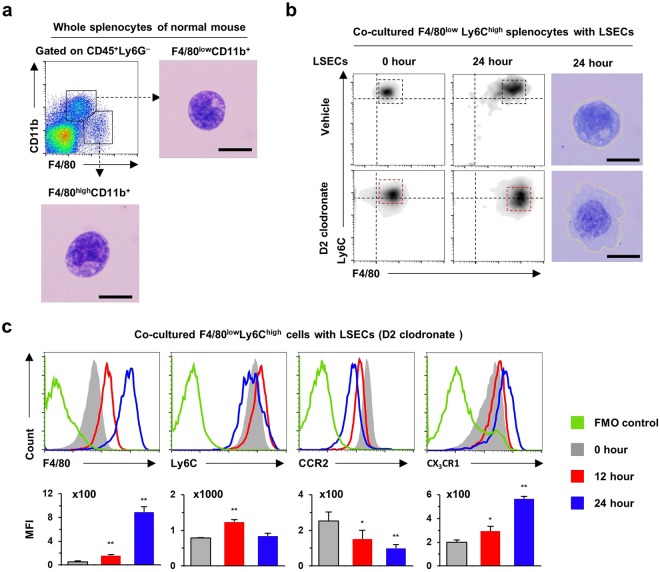

LSECs regulate F4/80 and CX3CR1 expression in splenic monocytes

To confirm whether differentiation of splenic F4/80low monocytes into F4/80high macrophages could be reproducible similar to circulating blood F4/80low monocytes in the liver, splenic F4/80low monocytes were co-cultured with LSECs of D2 clodronate-treated mouse liver. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that freshly isolated splenic F4/80lowCD11b+ monocytes had morphology similar to that of hepatic F4/80lowCD11b+ monocytes, while splenic resident F4/80highCD11b+ macrophages had a smaller cytoplasm than F4/80highCD11b+ Kupffer cells (Fig. 2a). However, intriguingly, co-culturing with LSECs gradually increased the expression of F4/80 in splenic F4/80lowCD11b+ monocytes and their morphology resembled the appearance of F4/80highCD11b+ Kupffer cells (Fig. 2b). Histogram analysis showed that co-culturing with LSECs increased the expression of F4/80 and CX3CR1, whereas the expression of CCR2 and Ly6C decreased in co-cultured splenic F4/80highCD11b+ monocytes at 24 h (Fig. 2c). These findings suggested that LSECs are important in the differentiation of CX3CR1lowF4/80low monocytes into CX3CR1highF4/80high macrophages.

Figure 2.

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells up-regulate expression of F4/80 and CX3CR1 in splenic Ly6C+ monocytes. (a) Isolated F4/80lowCD11b+ monocytes and F4/80highCD11b+ macrophages of spleen were subjected to Giemsa staining. Bar = 10 μm. (b,c) Splenic F4/80lowLy6C+ monocytes were co-cultured with LSECs of vehicle or D2 clodronate-treated mice for 24 h. They were subjected to flow cytometry and Giemsa staining. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to 0 h. The results represent three independent experiments.

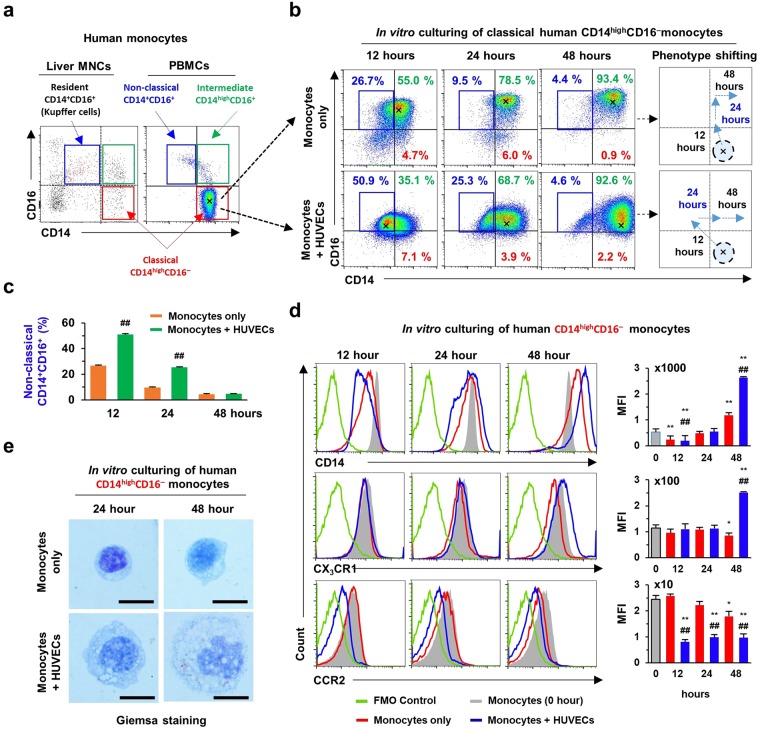

HUVECs regulate phenotypes of human classical CD14highCD16− monocytes

Next, we determined whether CX3CL1+ endothelial cells drive the differentiation of human CD14highCD16− monocytes into CX3CR1highCD14highCD16+ macrophages. As previously reported18, flow cytometry revealed three subsets of human monocytes in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and liver mononuclear cells (MNCs): classical, intermediate, and non-classical monocytes, were detected (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Therefore, isolated CD14highCD16− monocytes were co-cultured with HUVECs for 48 h. During in vitro co-culturing, most classical CD14highCD16− monocytes shifted towards intermediate CD14highCD16+ monocytes with or without co-culturing of HUVECs at 48 h (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Unlike culturing of only monocytes, classical CD14highCD16− monocytes temporarily shifted to CD14+CD16+ non-classical phenotype after being co-cultured with HUVECs at 12 h and further shifted towards the intermediate phenotype at 24 h (Fig. 3b,c). Histogram analysis revealed that CX3CR1 expression increased significantly in CD14highCD16− monocytes co-cultured with HUVECs but decreased in classical monocytes cultured without HUVECs (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 2c). However, CCR2 expression was reduced in both monocytes cultured alone or with HUVECs, whereas expression of CD68 and CD206 was further increased in monocytes cultured in the absence of HUVECs than in the presence of HUVECs (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 2d). Morphological observations showed that freshly isolated human blood monocytes had large and non-lobulated nuclei with scant cytoplasm (Supplementary Fig. 2a), whereas the cytoplasm volume in monocytes increased gradually during in vitro culture, and nuclei of cells became more peripherally located (Fig. 3e). These observations were more significant in monocytes co-cultured with HUVECs (Fig. 3e). These observations suggested that classical CD14highCD16− monocytes differentiate towards the intermediate or non-classical CX3CR1+CD14+CD16+ macrophages during co-culturing with HUVECs.

Figure 3.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) differentiate human CD14highCD16− monocytes into CD14+CD16+ monocytes along with high expression of CX3CR1. (a) Specific monocyte subsets were separated in human liver MNCs and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). (b,c) Human CD14highCD16− monocytes were co-cultured with HUVECs for 48 h. Then, their phenotypic shifts with respect to the expression of CD16 and CD14 were analyzed by flow cytometry and indicated by arrows and asterisks. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared to corresponding monocytes only (d) Expression of CD14, CX3CR1 and CCR2 in cultured CD14highCD16− monocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry and compared to those of human liver monocyte subsets. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to 0 h. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared to corresponding monocytes only. (e) Morphological changes of co-cultured CD14highCD16− monocytes were assessed after Giemsa staining. Bar = 10 μm. The results represent three independent experiments.

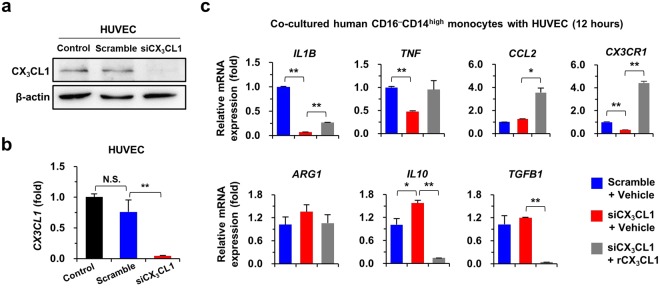

CX3CL1 of HUVECs regulates inflammatory phenotypes of human CD14highCD16− monocytes

Based on the preceding findings, we investigated whether HUVEC-derived CX3CL1 regulates the inflammatory phenotype of human CD14highCD16− monocytes. siRNA was used to silence CX3CL1 expression in HUVECs (Fig. 4a,b). CD14highCD16− monocytes co-cultured with CX3CL1-depleted HUVECs showed decreased expression of pro-inflammatory genes (IL1B and TNF), but slight increases in the expression of anti-inflammatory genes (ARG1, IL10, and TGFB1) (Fig. 4c). In contrast, treatment with recombinant CX3CL1 reversed the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory genes in co-cultured monocytes (Fig. 4c). These results suggested that CX3CL1 of HUVECs regulates inflammatory signals of co-cultured CD14highCD16− monocytes.

Figure 4.

CX3CL1 of HUVECs promote pro-inflammatory phenotype of human CD14highCD16− monocytes. (a,b) Silencing of CX3CL1 expression was assessed by western blot (a) and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) (b) in HUVECs after small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection. Original western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. (c) CD14highCD16− monocytes of human PBMCs were co-cultured with HUVECs for 12 h with or without treatment of recombinant CX3CL1. Co-cultured CD14highCD16− monocytes were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to corresponding control. The results represent three independent experiments.

CX3CR1 expression regulates inflammatory phenotypes of F4/80highCD11b+ macrophages in the liver

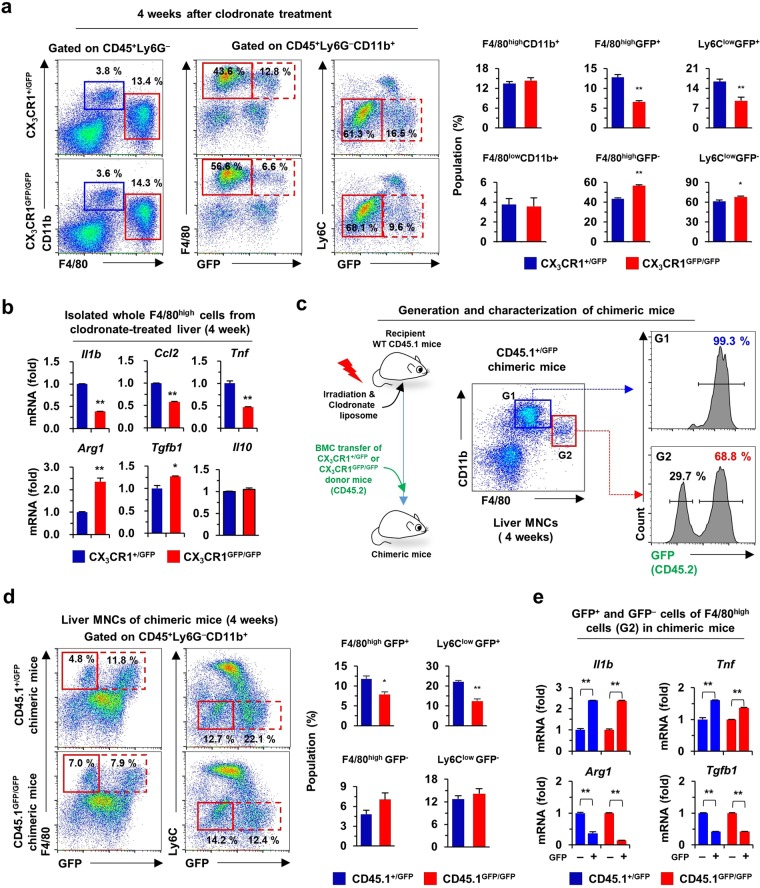

Next, we investigated the differentiation and pro-inflammatory roles of CX3CR1 in F4/80+CD11b+ macrophage subsets (F4/80high and F4/80low) of liver using clodronate liposome-treated CX3CR1 knock-in mice (CX3CR1+/GFP and CX3CR1GFP/GFP). In normal liver, similar frequencies of GFP+ (Cx3cr1 gene-expressing) cells were detected in F4/80high and F4/80low macrophage subsets of both CX3CR1+/GFP and CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice. By contrast the number of GFP+ cells were significantly increased in a F4/80low macrophage subset in both CX3CR1+/GFP and CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice after clodronate liposome-induced depletion of resident F4/80+ macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). At 4 weeks, the depleted F4/80high macrophage subset recovered to a similar extent in both CX3CR1 knock-in mice, suggesting that CX3CR1 is not critical for replacement of the resident F4/80high macrophage subset (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 4c). However, the frequencies of GFP+ cells in a F4/80high macrophage subset (or Ly6Clow) were significantly reduced in CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice compared to those in CX3CR1+/GFP mice (Fig. 5a). qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated the reduced expression of Il1b, Ccl2, and Tnf, whereas the expression of Arg1 and Tgfb1 was significantly elevated in a F4/80high macrophage subset of CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice compared to those of CX3CR1+/GFP mice (Fig. 5b). The findings suggested that high frequencies of CX3CR1-expressing cells might affect the elevated expression of pro-inflammatory genes in a F4/80high macrophage subset during replacement of F4/80+ macrophage subsets. To further confirm this suggestion, chimeric mice (recipient WT mice with CD45.1 expression) were generated by transplantation of bone marrow cells of CX3CR1+/GFP and CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice (with expression of CD45.2) after irradiation plus clodronate liposome treatment (Fig. 5c). At week 4, chimeric mice were euthanized to assess the chimerism of hepatic F4/80+ macrophages. Flow cytometry revealed that almost all (99.3 ± 0.6%) F4/80lowCD11b+ monocytes (G1 gating) were replaced from the GFP+ donor bone marrow cells, whereas GFP+CD45.2+ (68.8 ± 0.8%) and GFP−CD45.1+ (29.7 ± 0.5%) F4/80high CD11b+ macrophages (G2 gating) were replaced from donor and recipient mice, respectively (Fig. 5c). More interestingly, the number of GFP+ cells of a F4/80high macrophage subset (Ly6Clow macrophages) were significantly increased in CD45.1+/GFP chimeric mice compared to CD45.1GFP/GFP chimeric mice (Fig. 5d). Moreover, GFP+F4/80high macrophages showed an increased pro-inflammatory phenotype compared to GFP−F4/80high macrophages in both CD45.1+/GFP and CD45.1GFP/GFP chimeric mice (Fig. 5e), suggesting that the frequencies of CX3CR1-expressing cells among the F4/80high macrophage subset might influence inflammation in liver injury.

Figure 5.

CX3CR1 expression assigns two subsets and pro-inflammatory phenotype to F4/80high or Ly6Clow macrophages in the liver. (a) Liver monocytes and macrophages were analyzed by flow cytometry using isolated liver MNCs of CX3CR1+/GFP and CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice and 4-week after clodronate liposome treatment. (b) Isolated whole F4/80high cells were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis at week 4 after clodronate liposome treatment. (c) To generate chimeric mice, recipient wild type mice (CD45.1) were transplanted with donor bone marrow cells (BMC) of CX3CR1+/GFP or CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice (CD45.2) after irradiation and clodronate liposome treatment. Chimerism was assessed by expression of GFP (CD45.2) in liver MNCs of recipient mice. (d) Isolated liver MNCs from chimeric mice were subjected to flow cytometry. (e) F4/80highGFP+ and F4/80highGFP− cells of chimeric mice were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to GFP− F4/80high cells. The results represent two independent experiments.

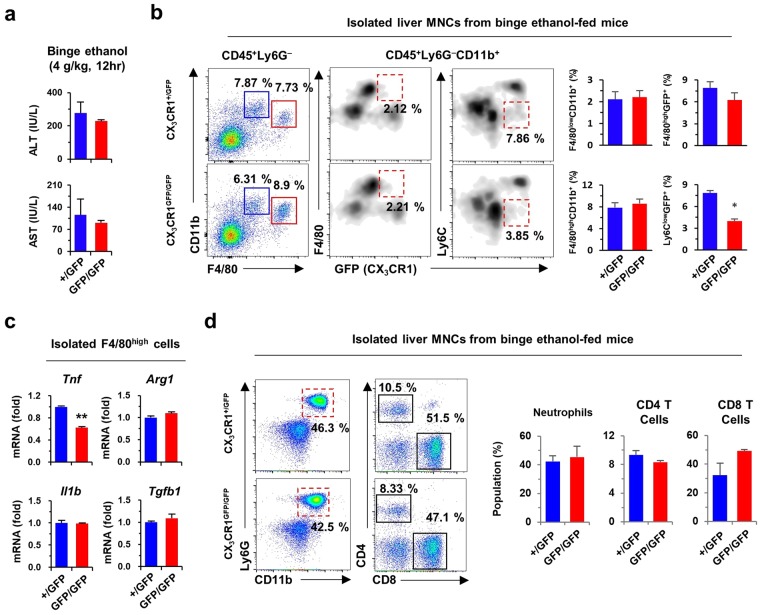

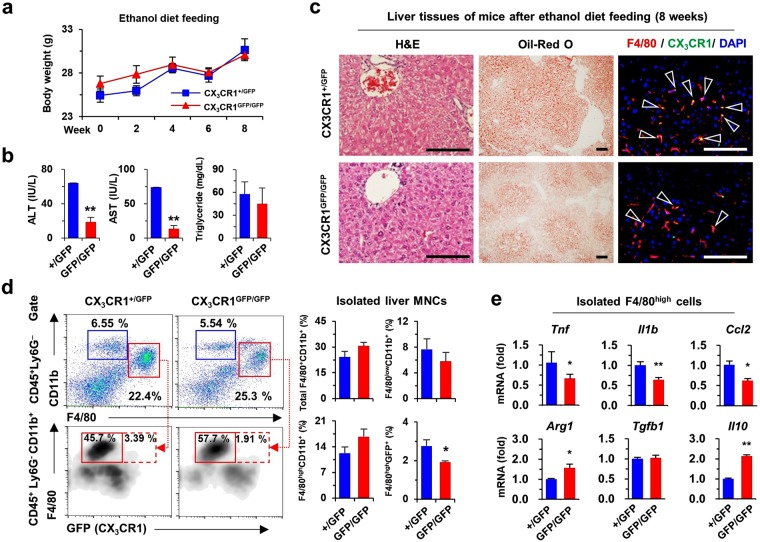

CX3CR1 deficiency attenuates ethanol-induced liver injury

To investigate the pro-inflammatory effect of CX3CR1+F4/80high macrophages, liver injury was induced by binge ethanol drinking or an 8-week diet of liquid ethanol in CX3CR1+/GFP and CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice. Acute liver injury was not associated with significant differences in serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and altered frequencies of F4/80highCD11b+ Kupffer cells including CX3CR1+F4/80high cells between CX3CR1+/GFP and CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice (Fig. 6a,b and Supplementary Fig. 5a). However, CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice showed lower expression of TNF-α than CX3CR1+/GFP mice, although similar hepatic expression of CX3CL1 in response to acute liver injury was evident (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 5b). Additionally, there were no differences in the frequencies of Ly6G+CD11b+ neutrophils, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells in CX3CR1+/GFP and CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice (Fig. 6d). The chronic ethanol diet did not result in significant changes in the body weights of CX3CR1GFP/GFP and CX3CR1+/GFP mice (Fig. 7a), but serum levels of ALT and AST in CX3CR1-deficient (CX3CR1GFP/GFP) mice was significantly reduced compared to CX3CR1+/GFP mice (Fig. 7b). Histological observations revealed reduced fat accumulation and infiltration of CX3CR1+F4/80+ cells in the livers of CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice compared to CX3CR1+/GFP mice (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Fig. 5c). Flow cytometry analyses revealed similar frequencies of total F4/80+CD11b+ cells in CX3CR1GFP/GFP and CX3CR1+/GFP mice (Fig. 7d). However, pro-inflammatory CX3CR1+ cells of F4/80high macrophages (CX3CR1+F4/80high) were significantly lower in the livers of CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice than in CX3CR1+/GFP mice, although there was no difference in the frequency of F4/80highCD11b+ macrophages between both mice (Fig. 7d). F4/80high macrophages of CX3CR1+/GFP mice displayed a more pro-inflammatory phenotype than CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice (Fig. 7e). However, frequencies of other immune cells including CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T Cells, NK cells, dendritic cells and neutrophils were similar, and expression of Ifng, Il17, Il4, and Il13 in liver MNCs was not different between both mice (Supplementary Fig. 5d,e). Consistent with these observations, the increased expression of Cx3cl1 and Cx3cr1 in the GEO database (GSE97234) was significantly associated with high expression of Il1β and Tnf in mice with alcoholic steatohepatitis compared to healthy control mice (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). These observations suggested that pro-inflammatory CX3CR1+F4/80high macrophages contribute to alcoholic liver injury.

Figure 6.

CX3CR1 deficiency attenuates acute alcoholic liver injury. To induce acute alcoholic liver injury, CX3CR1+/GFP (n = 4) and CX3CR1GFP/GFP (n = 4) mice were fed 4 g/kg ethanol (binge ethanol drinking). (a) Serum levels of ALT and AST were measured in binge ethanol-fed mice. (b,c) Isolated liver MNCs and F4/80high cells from binge ethanol-fed mice were subjected to flow cytometry and qRT-PCR analysis, respectively. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to corresponding controls. (d) Isolated liver MNCs from binge ethanol-fed mice were subjected to flow cytometry. The results represent two independent experiments.

Figure 7.

CX3CR1 deficiency attenuates alcoholic liver injury. CX3CR1+/GFP (n = 4) and CX3CR1GFP/GFP (n = 4) mice were fed 5% liquid ethanol diet for 8 weeks. (a,b) Body weight changes and serum levels of ALT, AST, and triglyceride were measured. (c) Liver sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) and Oil-Red O, or with F4/80 antibody. Bar = 100 μm. (d) Isolated liver MNCs were subjected to flow cytometry. (e) Isolated F4/80high cells were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to corresponding controls. The results represent two independent experiments.

Discussion

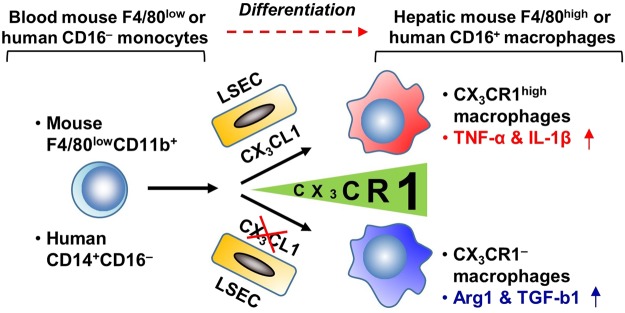

Recent developments in gene editing techniques have enabled fate-map tracing of tissue-resident macrophages. Nevertheless, most studies have focused on the origins of macrophages4–6. In the present study, we investigated whether CX3CR1 might be involved in the differentiation of circulating blood monocytes into hepatic resident macrophages in mice and humans. We observed that F4/80lowCX3CR1low monocytes were converted into pro-inflammatory F4/80highCX3CR1high macrophages via interaction with endothelial cells in vitro, and that CX3CR1 deficiency ameliorated alcoholic liver injury in mice by decreasing the number of pro-inflammatory F4/80highCX3CR1high macrophages (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic summary. CX3CR1 differentiates mouse monocytes (F4/80lowCD11b+) and human monocytes (CD14+CD16−) into pro-inflammatory macrophages. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) express CX3CL1 in the liver.

There are at least two distinct monocyte subsets in humans and mice: the classical mouse Ly6Chigh or human CD14highCD16− monocytes and non-classical mouse Ly6Clow or human CD14lowCD16+ monocytes25. The non-classical monocytes express higher levels of CX3CR1 and lower levels of CCR2 than classical monocytes in both mice and humans18,25. These non-classical Ly6Clow and CD14lowCD16+ monocytes contribute to the maintenance of endothelial integrity, whereas classical Ly6C+ monocytes participate in the inflammatory response14,25,26. During liver inflammation, classical Ly6Chigh monocytes migrate rapidly to sites of injury, mainly in a CCR2-dependent manner, where they differentiate into functional macrophages and exert either a pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory function with the assistance of local environments25–27. Interestingly, among F4/80lowCD11b+ monocytes in the liver, the Ly6Clow subset of monocytes participates in the resolution of liver injury and tissue repair, whereas the Ly6Chigh subset of monocytes presents a pro-inflammatory phenotype11–13. However, resident F4/80highCD11b+ macrophage subsets and their functional phenotypes have not been investigated in the liver.

F4/80highCD11b+ Kupffer cells or resident macrophages play crucial roles in immune tolerance during the normal steady state and also in the inflammatory state18. In the non-inflammatory state, Kupffer cells remove detrimental materials such as injured cells, microbes, toxic materials, and immune complexes, to prevent excess immune response and maintain homeostasis1. On the contrary, Kupffer cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and CCL2, due to excessive stimulation by endotoxins or exotoxins18. However, whether particular subsets of the Kupffer cell population have pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory characteristics is still unclear. Moreover, tissue-resident macrophages might originate from circulating Ly6Chigh monocytes in the inflammatory state in severe infection, tumor environment, and tissue regeneration25. The present results support the suggestion that CX3CR1 is an important factor for the differentiation of circulating Ly6ChighF4/80lowCX3CR1low monocytes into inflammatory CX3CR1highF4/80highLy6Clow macrophages (a new subset), while pre-existing F4/80highLy6Clow Kupffer cells are negative for CX3CR1 in the steady state5,28. After depletion of Kupffer cells by clodronate liposome treatment, considerable numbers of repopulated F4/80highCD11b+ macrophages were CX3CR1 positive (approximately 13%) compared to those (approximately 2.4%) in control CX3CR1+/GFP mice, whereas they were significantly reduced in CX3CR1 deficient mice (approximately 6%). LSECs line the liver sinusoids and provide a platform for the adhesion of diverse immune cells, including Kupffer cells29. However, the exact molecular mechanisms by which circulating monocytes differentiate into resident macrophages remain unclear. We observed that LSECs definitely augment the differentiation of circulating blood and splenic monocytes into resident CX3CR1highF4/80highLy6Clow or CX3CR1highCD14+CD16+ macrophages, and partially assign pro-inflammatory characteristics to resident macrophages in a CX3CR1-CX3CL1-dependent manner in both mice and humans. These functional and phenotypical features allow the separation of the two subsets of F4/80highCD11b+ macrophages in the liver. In terms of CX3CL1, there are two different forms of CX3CL1. Soluble CX3CL1 generated by proteolytic cleavage has a chemoattractive function. Membrane-bound CX3CL1 functions as an adhesion molecule30. Although we could not examine soluble CX3CL1 of HUVECs, siRNA-mediated depletion of CX3CL1 in HUVECs decreased the expression of pro-inflammatory genes in adherent human CD14+CD16− monocytes. Recombinant CX3CL1 treatment reversed the expression of the pro-inflammatory genes. These results suggest that both membrane-bound CX3CL1 and soluble CX3CL1 can change the function of CX3CR1+ monocytes. However several studies have reported that CX3CR1high macrophages generally have anti-inflammatory characteristics in the intestine but CX3CR1intLy6Chigh cells show pro-inflammatory phenotype in an inflamed colon31,32. Therefore, further studies of CX3CR1 expressing macrophages are required.

Alcoholic liver disease is one of the main causes of chronic liver disease, in which hepatic macrophages play a critical role during the progression of alcoholic liver disease33–36. The number of macrophages and the circulating levels of CCL2 are increased by high endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels in patients with alcoholic liver disease37–39. These findings suggest that infiltrated macrophages originating from circulating monocytes could be important in alcoholic liver disease. In support of this idea, Wang et al. reported that chronic alcohol consumption can recruit pro-inflammatory Ly6Chigh or anti-inflammatory Ly6Clow cell subsets of F4/80low monocytes40. However, the F4/80high subset of macrophages has not yet been investigated. Interestingly, increased serum CX3CL1 level correlates with chronic liver diseases, such as liver fibrosis, and CX3CR1 regulates the differentiation and survival of infiltrating monocytes in the liver of mice to limit fibrosis20. Therefore, the interplay between CX3CR1 and CX3CL1 might affect the progression of alcoholic liver disease. However, intriguingly, we demonstrated an opposing and detrimental effect of CX3CR1 in alcoholic liver disease compared to non-alcoholic liver disease, where CX3CR1 accelerated hepatic fat accumulation and liver injury were accompanied by the increased frequency of the pro-inflammatory F4/80highCD11b+ macrophage subset. These contradictory roles of CX3CR1 might be due to the differential activation of macrophage subsets during liver injury. In contrast to the infiltration of large numbers of F4/80lowCD11b+ monocytes in non-alcoholic liver injury, resident F4/80highCD11b+ macrophages, including Kupffer cells, are the predominant inflammatory cells in alcoholic liver injury and are sensitized by up-regulated endotoxin levels in portal circulation41. In a human endotoxemia model, endotoxin treatment increased the frequency of non-classical CD14+CD16+ monocytes in the blood, due to endotoxin-mediated conversion of circulating classical CD14highCD16− monocytes into CD14+CD16+ monocytes42. This human study strongly indicates a possible mechanism of endotoxin-mediated differentiation of circulating classical monocytes into resident-like phenotype of macrophages. However, further studies are required for definitive conclusions.

Conclusion

CX3CR1 plays important roles in the phenotypic conversion and pro-inflammatory functional polarization of hepatic monocytes. CX3CR1 could be a specific marker for separating resident macrophage subsets and may be a novel therapeutic target in alcoholic liver disease.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male wild-type (WT) mice with a C57BL/6 or B6/SJL (CD45.1) background and CX3CR1 knock-in mice with green fluorescence protein (GFP) (CX3CR1GFP/GFP) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). CX3CR1+/GFP mice with GFP substitution in only one CX3CR1 allele were used as reporters to identify CX3CR1-expressing monocytes/macrophages. GFP-expressing CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice were considered a s CX3CR1 knock-out mice43. Male WT mice with a C57BL/6 or B6/SJL (CD45.1) background were used for the generation of chimeric mice. All animals were maintained according to the guidelines of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health. The protocol for animal experiment was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Korea Advanced Institute for Science and Technology. All mice were euthanized under anesthesia (Ketamine, Yuhan, Korea), then blood, liver, and spleen were harvested.

Ethanol-induced liver injury

For binge ethanol drinking model, 4 g/kg ethanol was administered to mice by gavage. After 12 h the mice were euthanized. To induce chronic ethanol-induced liver injury, mice were fed a 5% Lieber-DeCarli ethanol liquid diet (Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA) for 8 weeks. The liquid diet was replaced daily to prevent evaporation of ethanol. After 8 weeks, the mice were euthanized and liver injury was evaluated.

Isolation of mouse liver non-parenchymal cells

Liver non-parenchymal cells were isolated as previously described44,45. Briefly, the liver was washed with EGTA solution (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and digested with type 1 collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ) through the portal vein. Hepatic non-parenchymal cells were separated from hepatocytes by centrifugation. HSCs were separated from non-parenchymal cells using Optiprep gradient solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Monocytes and Kupffer cells were isolated using the FACS Aria III device (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) were separated using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) with anti-CD146-PE and anti-PE beads (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA) following manufacturer’s protocol.

Human samples

Liver tissue of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and blood of healthy donors were obtained from the archives of the Department of Surgery and the Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital (Daejeon, South Korea) and the Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Guro Hospital (Seoul, South Korea), respectively. The study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Authorization for the use of these tissues and blood for research purposes was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Chungnam National University Hospital (Number: 2016-03-02-003) and Korea University Guro hospital (KUGH16121-001). Informed consent was obtained from all patients who had provided tissue or blood.

Isolation of human liver mononuclear cells (MNCs) and PBMCs

Human liver MNCs were isolated as previously described45 from non-tumor regions of liver tissue from patients with hepatic cellular carcinoma. Liver MNCs were isolated using a GentleMACS™ dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Blood from healthy donors were used for isolation of human PBMCs. The collected blood was centrifuged at 1,600 rpm for 10 min. Plasma was harvested and the buffy coat was suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The suspended buffy coat was loaded on Ficoll (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) and centrifuged for 20 min at 2,000 rpm without brake. PBMCs were harvested from the interphase.

Clodronate liposome treatment

For depletion of Kupffer cells and resident macrophages, 1 mg clodronate liposomes (Haarlem, Netherlands) were injected intraperitoneally in each mouse. Depletion was confirmed 2 days after the injection. The same concentration of PBS liposomes was injected intraperitoneally as a control.

Generation of chimeric mice

Chimeric mice were generated as previously described44,45. Briefly, the mice were irradiated at dose of a 950 Rad. After irradiation, total BMCs (3 × 106 cells) from donor mice were injected via the tail vein. To deplete the recipient’s Kupffer cells, clodronate liposome treatment was performed 2 days prior to the transplantation of BMCs.

Co-culture of mouse and human monocytes with mouse LSECs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)

To differentiate macrophages from monocytes, 2 × 105 monocytes obtained from mouse liver or spleen were co-plated with 5 × 105 LSECs and co-cultured for 24 h. In some experiments, whole liver non-parenchymal cells (5 × 105) were cultured for 24 h. Isolated human CD14+ monocytes (5 × 105) from PBMCs were co-cultured with 5 × 105 HUVECs for 48 h. After detachment, co-cultured monocytes were subjected to flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Cells were washed twice with Dulbecco’s PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% sodium azide. After washing, the cells were stained with LIVE/DEADTM Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cells were stained with fluorescence-conjugated surface antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C, washed, and analyzed using LSR II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). The data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). Antibodies used for flow cytometric analyses included: APC-Cy7 CD11b (M1/70), APC CD11b (M1/70), PerCP-Cy5.5 Ly6G (1A8), FITC Ly6C (AL21), PerCP-Cy5.5 Ly6C (AL-21), PerCP-Cy5.5 CD45.1 (A20), PE-Cy7 CD3e (145-2C11) PerCP-Cy5.5 CD4 (RM4-5), APC CD8a (53-6.7), and PE NK1.1 (PK136) (all from BD Bioscience); PE-Cy7 F4/80 (BM8), PE F4/80 (BM8) eFluor® 450 CD45 (30-F11) (all from eBioscience, San Diego, CA); PE CX3CR1 (polyclonal) and APC CCR2 (#475301) (both from R&D Systems, Madison, WI) for mouse. BV421 CD45 (HI30), PE CD14 (MφP9), and PerCP-Cy5.5 CD16 (3G8) (all from BD Bioscience); FITC CD68 (Y1/82A), APC CX3CR1 (FN50), and APC-Cy7 CCR2 (REA264) (all from eBioscience) and APC CD206 (19.2) (Biolegend, San diego, CA) for human.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. To compare values obtained from two or more groups, Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA was performed. P values < 0.01 or 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (2015R1A2A1A10055551), the Korea Mouse Phenotyping Project (2014M3A9D5A01073556) of the National Research Foundation funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT, the Intelligent Synthetic Biology Center of Global Frontier Project funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (2011-0031955) Republic of Korea and the Gilead Sciences Research Scholars Program in Liver Disease-Asia through Gilead Sciences.

Author Contributions

Y.S.L., M.H.K. and W.I.J. contributed to the design and performance of experiments and analysis of data. S.Y.K., H.S.Y., H.H.K. and Y.S.L. contributed to the isolation of human monocytes and PBMCs from patients and flow cytometry analysis. J.H.K., J.E.Y. and K.S.B. analyzed human data. J.S.B. and W.I.J. wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Young-Sun Lee and Myung-Ho Kim contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Jin-Seok Byun, Email: jsbyun@knu.ac.kr.

Won-Il Jeong, Email: wijeong@kaist.ac.kr.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-33440-9.

References

- 1.Gao B, Jeong WI, Tian Z. Liver: An organ with predominant innate immunity. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2008;47:729–736. doi: 10.1002/hep.22034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krenkel O, Tacke F. Liver macrophages in tissue homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:306–321. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jager J, Aparicio-Vergara M, Aouadi M. Liver innate immune cells and insulin resistance: the multiple facets of Kupffer cells. Journal of internal medicine. 2016;280:209–220. doi: 10.1111/joim.12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheng J, Ruedl C, Karjalainen K. Most Tissue-Resident Macrophages Except Microglia Are Derived from Fetal Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Immunity. 2015;43:382–393. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yona S, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perdiguero EG, et al. The Origin of Tissue-Resident Macrophages: When an Erythro-myeloid Progenitor Is an Erythro-myeloid Progenitor. Immunity. 2015;43:1023–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein I, et al. Kupffer cell heterogeneity: functional properties of bone marrow derived and sessile hepatic macrophages. Blood. 2007;110:4077–4085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zigmond E, et al. Infiltrating Monocyte-Derived Macrophages and Resident Kupffer Cells Display Different Ontogeny and Functions in Acute Liver Injury. The Journal of Immunology. 2014;193:344–353. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hettinger J, et al. Origin of monocytes and macrophages in a committed progenitor. Nature immunology. 2013;14:821–830. doi: 10.1038/ni.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmermann HW, et al. Functional contribution of elevated circulating and hepatic non-classical CD14CD16 monocytes to inflammation and human liver fibrosis. PloS one. 2010;5:e11049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dal-Secco D, et al. A dynamic spectrum of monocytes arising from the in situ reprogramming of CCR2+ monocytes at a site of sterile injury. J Exp Med. 2015;212:447–456. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell C, et al. Dual role of CCR2 in the constitution and the resolution of liver fibrosis in mice. The American journal of pathology. 2009;174:1766–1775. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramachandran P, et al. Differential Ly-6C expression identifies the recruited macrophage phenotype, which orchestrates the regression of murine liver fibrosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:E3186–3195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119964109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlin LM, et al. Nr4a1-dependent Ly6C(low) monocytes monitor endothelial cells and orchestrate their disposal. Cell. 2013;153:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mass, E. et al. Specification of tissue-resident macrophages during organogenesis. Science (New York, N.Y.)353 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Landsman L, et al. CX3CR1 is required for monocyte homeostasis and atherogenesis by promoting cell survival. Blood. 2009;113:963–972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee YS, et al. The fractalkine/CX3CR1 system regulates beta cell function and insulin secretion. Cell. 2013;153:413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmermann HW, Trautwein C, Tacke F. Functional role of monocytes and macrophages for the inflammatory response in acute liver injury. Frontiers in physiology. 2012;3:56. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aoyama T, Inokuchi S, Brenner DA, Seki E. CX3CL1-CX3CR1 interaction prevents carbon tetrachloride-induced liver inflammation and fibrosis in mice. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2010;52:1390–1400. doi: 10.1002/hep.23795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karlmark KR, et al. The fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 protects against liver fibrosis by controlling differentiation and survival of infiltrating hepatic monocytes. Hepatology. 2010;52:1769–1782. doi: 10.1002/hep.23894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Efsen E, et al. Up-regulated expression of fractalkine and its receptor CX3CR1 during liver injury in humans. Journal of hepatology. 2002;37:39–47. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00065-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wasmuth HE, et al. The fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 is involved in liver fibrosis due to chronic hepatitis C infection. Journal of hepatology. 2008;48:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babendreyer A, Molls L, Dreymueller D, Uhlig S, Ludwig A. Shear Stress Counteracts Endothelial CX3CL1 Induction and Monocytic Cell Adhesion. Mediators of inflammation. 2017;2017:1515389. doi: 10.1155/2017/1515389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haskell CA, Cleary MD, Charo IF. Molecular uncoupling of fractalkine-mediated cell adhesion and signal transduction. Rapid flow arrest of CX3CR1-expressing cells is independent of G-protein activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:10053–10058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ginhoux F, Jung S. Monocytes and macrophages: developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dambach DM, Watson LM, Gray KR, Durham SK, Laskin DL. Role of CCR2 in macrophage migration into the liver during acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in the mouse. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2002;35:1093–1103. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miura K, Yang L, van Rooijen N, Ohnishi H, Seki E. Hepatic recruitment of macrophages promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through CCR2. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2012;302:G1310–1321. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00365.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heymann F, et al. Liver inflammation abrogates immunological tolerance induced by Kupffer cells. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2015;62:279–291. doi: 10.1002/hep.27793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knolle PA, Wohlleber D. Immunological functions of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2016;13:347–353. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2016.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones BA, Beamer M, Ahmed S. Fractalkine/CX3CL1: A Potential New Target for Inflammatory Diseases. Molecular Interventions. 2010;10:263–270. doi: 10.1124/mi.10.5.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gross M, Salame TM, Jung S. Guardians of the Gut - Murine Intestinal Macrophages and Dendritic Cells. Front Immunol. 2015;6:254. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zigmond E, et al. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2012;37:1076–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao B, et al. Innate immunity in alcoholic liver disease. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2011;300:G516–525. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00537.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ju C, Mandrekar P. Macrophages and Alcohol-Related Liver Inflammation. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2015;37:251–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah VH. Managing alcoholic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21:212–219. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2015.21.3.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jang JY, Kim DJ. Epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease in Korea. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;24:93–99. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2017.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karakucuk I, Dilly SA, Maxwell JD. Portal tract macrophages are increased in alcoholic liver disease. Histopathology. 1989;14:245–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1989.tb02143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afford SC, et al. Distinct patterns of chemokine expression are associated with leukocyte recruitment in alcoholic hepatitis and alcoholic cirrhosis. The Journal of pathology. 1998;186:82–89. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199809)186:1<82::AID-PATH151>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher NC, Neil DA, Williams A, Adams DH. Serum concentrations and peripheral secretion of the beta chemokines monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 and macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha in alcoholic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:416–420. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.3.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang M, et al. Chronic alcohol ingestion modulates hepatic macrophage populations and functions in mice. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2014;96:657–665. doi: 10.1189/jlb.6A0114-004RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagy LE. The Role of Innate Immunity in Alcoholic Liver Disease. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2015;37:237–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel AA, et al. The fate and lifespan of human monocyte subsets in steady state and systemic inflammation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2017;214:1913–1923. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jung S, et al. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20:4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yi HS, et al. Alcohol dehydrogenase III exacerbates liver fibrosis by enhancing stellate cell activation and suppressing natural killer cells in mice. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2014;60:1044–1053. doi: 10.1002/hep.27137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim SY, et al. Pro-inflammatory hepatic macrophages generate ROS through NADPH oxidase 2 via endocytosis of monomeric TLR4-MD2 complex. Nat Commun. 2017;8:2247. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02325-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.