Abstract

Changes in permeability of retinal blood vessels contribute to macular edema and the pathophysiology of numerous ocular diseases, including diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusions, and macular degeneration. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induces retinal permeability and macular thickening in these diseases. However, inflammatory agents, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), also may drive vascular permeability, specifically in patients unresponsive to anti-VEGF therapy. Recent evidence suggests VEGF and TNF-α induce permeability through distinct mechanisms; however, both require the activation of atypical protein kinase C (aPKC). We provide evidence, using genetic mouse models and therapeutic intervention with small molecules, that inhibition of aPKC prevented or reduced vascular permeability in animal models of retinal inflammation. Expression of a kinase-dead aPKC transgene, driven by a vascular and hematopoietic restricted promoter, reduced retinal vascular permeability in an ischemia-reperfusion model of retinal injury. This effect was recapitulated with a small-molecule inhibitor of aPKC. Expression of the kinase-dead aPKC transgene dramatically reduced the expression of inflammatory factors and blocked the attraction of inflammatory monocytes and granulocytes after ischemic injury. Coinjection of VEGF with TNF-α was sufficient to induce permeability, edema, and retinal inflammation, and treatment with an aPKC inhibitor prevented VEGF/TNF-α–induced permeability. These data suggest that aPKC contributes to inflammation-driven retinal vascular pathology and may be an attractive target for therapeutic intervention.

Increased retinal vascular permeability, leading to fluid accumulation, retinal swelling, and macular edema (ME), contributes to blindness in a host of ocular diseases, including diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusions, age-related macular degeneration, and uveitis.1, 2, 3, 4 ME disrupts macular structure and function and is one of the most common causes of blindness in developed countries.4, 5 Loss of the blood-retinal barrier and an increase in retinal vascular permeability can contribute to ME.6, 7 Notably, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been identified as a key regulator of vascular permeability in the pathogenesis of ME.4 Agents aimed at reducing vascular permeability and improving macular edema are emerging as robust medical therapies. Large multicenter clinical trials have demonstrated that anti-VEGF therapies reduce ME and improve visual acuity in a large fraction of patients with diabetic retinopathy.8, 9, 10 Furthermore, clinical trials for both central and branch retinal vein occlusion revealed stark improvements of visual acuity and reduced ME after anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody treatment.1 However, not all patients benefit from anti-VEGF therapy, and inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), may also contribute to the disease process in diabetic retinopathy.11, 12, 13

Animal studies suggest that TNF-α and VEGF may contribute to different phases of vascular dysfunction in diabetic retinopathy. In a mouse model of diabetes, TNF-α gene deletion partially reduced vascular permeability at 3 months and completely blocked permeability at 6 months, but was without any affect at 1 month when VEGF drives permeability.11 More important, in small clinical studies of patients refractive to other treatments, anti–TNF-α therapies led to significant improvement in visual acuity compared with placebo-controlled eyes.14, 15 Indeed, therapies that prevent vascular permeability in response to both growth factors, such as VEGF, and inflammatory cytokines, like TNF-α, may prove to be highly effective in treating ME for a broad number of patients in an array of ocular diseases. Identifying commonalities of TNF-α and VEGF signaling may provide an opportune therapeutic target for ME.

The mechanism of VEGF-induced retinal vascular permeability includes phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation of occludin, a tight junction protein that regulates barrier properties,16, 17 whereas TNF-α–induced permeability involves NF-κB activation and down-regulation of other tight junction protein members, including claudin-5 and zonula occludens protein 1.18 However, endothelial cell permeability induced by VEGF, TNF-α, or a combination of VEGF and TNF-α is prevented by inhibition of atypical protein kinase C (aPKC).18, 19, 20

The atypical protein kinase C isoforms (ζ and ι) are part of the larger PKC family that mediates a range of important cellular processes, including proliferation, migration, differentiation, and cellular polarity. Gene deletion of aPKCζ (Prkcz) produces essentially normal mice.21 In contrast, PKCι/λ is required for formation of cell polarity, and Prkci gene deletion led to embryonic lethality.22 However, once polarity is established, inhibition of aPKC activities does not disrupt polarity or the junctional complex.23

Evidence from genetic loss-of-function studies suggests aPKC isoforms play a role in innate immune function.24 More important, Prkcz deletion severely impairs NF-κB–dependent gene transcription after either TNF-α or IL-1β treatment21 and is required for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM1) phosphorylation and leukocyte binding in response to TNF-α.25 Signaling downstream of aPKC also contributes to macrophage activation via nitric oxide synthase (NOS)2 in experimentally induced uveitis.26

Retinal vascular permeability is induced by a variety of factors, including VEGF, TNF-α, thrombin, and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2). More important, these permeabilizing agents signal through aPKC to alter vascular endothelial permeability, placing aPKC as a common downstream permeabilizing signaling node. Thrombin induces vascular permeability of endothelial cells and is effectively blocked by multiple methods inhibiting aPKC function.27 Blocking aPKC activity effectively reduces CCL2-induced brain microvascular permeability.28 Recently, our laboratory has demonstrated that aPKC isoforms mediate both TNF-α– and VEGF-induced blood-retinal barrier dysfunction and retinal vascular permeability, showing that a dominant kinase-dead aPKCζ (kdPKCζ), siRNA to aPKC, as well as specific small-molecule inhibitors to aPKC all prevent VEGF- and TNF-α–induced endothelial permeability.18, 20 A phenyl thiophene class of small-molecule inhibitors has been further refined and characterized as specific inhibitors of aPKC that block VEGF- and TNF-α−induced permeability.19 Therefore, targeting aPKC might provide a superior benefit by targeting a common pathway to vascular permeability, thereby maximizing biological efficacy.

In this report, we examine both genetic and small-molecule inhibition of aPKC using both terminal and nonterminal measures of vascular permeability and retinal edema in two models of sterile inflammation-driven retinal vascular permeability. Using the Tek promoter, previously called Tie2, vascular endothelial and myeloid conditional expression of kdPKCζ reduced ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury–induced vascular permeability, reduced both myeloid leukocytes and granulocyte infiltration, and reduced expression of several inflammation-related genes. This same effect on IR injury–induced permeability was recapitulated with a small-molecule inhibitor of aPKC. Furthermore, we demonstrate that coinjection of VEGF with the inflammatory factor TNF-α in the rat causes a robust increase in inflammation, as observed by myeloid and granulocyte infiltration, vascular permeability, and retinal edema. Again, treatment with a small-molecule inhibitor of aPKC prevented the vascular permeability. Collectively, genetic and small-molecule inhibition of aPKC proved effective at reducing retinal inflammation and vascular permeability in both models of retinal inflammation, suggesting aPKC may be an attractive target for therapeutic intervention during inflammatory eye disease.

Materials and Methods

Recombinant rat VEGF and TNF-α were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Chemicals, including PKC inhibitors, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or as indicated.

Animals

Male Long-Evans rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were used to evaluate retinal vascular permeability and tight junction protein localization. Male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were used to evaluate retinal vascular permeability. Animals were housed under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to water and a standard rodent chow. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and were approved and monitored by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI).

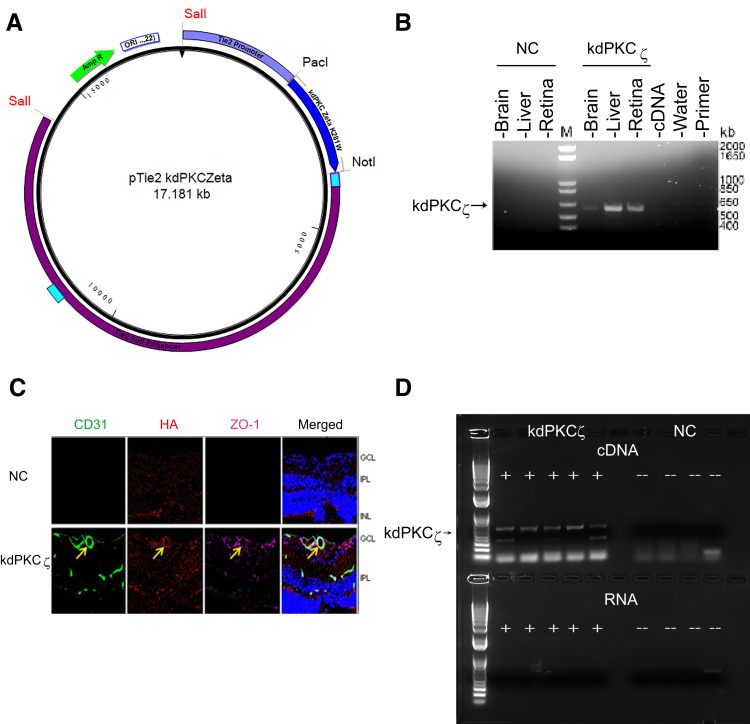

For these studies, a transgenic mouse was generated with conditional expression of kinase-dead aPKC containing the rat cDNA encoding a PKCζ isoform with a K281W mutation (kdPKCζ), originally described by Vasavada et al,29 under control of the TEK promoter with a 10-kb enhancer (kind gift from Dr. Thomas N. Sato, Advanced Telecommunications Research Institute International, Kyoto, Japan).30 The kdPKCζ also had an N-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) tag. C57BL/6Cr mouse embryos were injected with plasmid (Figure 1A) and implanted into pseudopregnant females, and founder strains were bred. Because of a viral infection in the founder strains, it was necessary to perform in vitro fertilization and only one of the four original founder strains was recovered. The transgenic strain was backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice through at least six generations. Mice were originally genotyped by PCR using primers 5′-GAGACTGTTACCGCCTGCTTCTGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGTTCTCGGAGGTCATCTACTGTT-3′ (reverse) within the Tek promoter and the rat Prkcz mutant gene, respectively. Transnetyx Inc. (Cordova, TN) performed additional genotyping with a proprietary set of PCR primers. The mouse strain was tested for Crb1 rd8 mutation and found negative. Mature transgenic and littermate noncarrier mice at approximately 5 months of age were used for all studies, except the nanoString (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA) gene expression analysis, in which 2-month–old animals were used.

Figure 1.

Expression of kdPKCζ in mouse tissues. A: Plasmid map of Tek-driven kdPKCζ DNA construct with enhancer. B: Expression of kdPKCζ in mouse tissues by PCR; noncarrier (NC) versus kdPKCζ water or primer alone. C: Analysis of kdPKCζ expression in the retina by immunofluorescence. Six-week–old kdPKCζ carrier and NC littermate mice were analyzed for the expression of hemagglutinin (HA) tag (red) along with endothelial marker CD31 (green) and zonula occludens protein 1 (ZO-1; far red) in retinal cross sections. Yellow arrows indicate expression of kdPKCζ in retinal blood vessel. D: Expression of kdPKCζ in the circulating leukocytes of kdPKCζ mice but not NC controls. The product was observed only after cDNA synthesis and not from RNA alone, indicating no genomic contamination. Original magnification, ×630 (C). GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; M, marker.

Intravitreal Injection

Male Long-Evans rats were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine. A 32-gauge needle was used to generate a hole for an intravitreal injection (2 μL/eye) using a 5-μL Hamilton syringe. Animals received an intravitreal injection of vehicle [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)], VEGF/TNF-α (50 ng/10 ng), or aPKC inhibitor ethyl 2-amino-4-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-thiophenecarboxylate (9.8 or 98 ng) to yield an estimated final concentration of 1 or 10 μmol/L (assuming a 30-μL vitreous volume). With the same procedure, mice were anesthetized and one eye was injected with 1 μL of 200 ng mouse VEGF while the other eye received 1 μL of vehicle (PBS).

Ischemia-Reperfusion

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine. Ischemia was applied to the eye by increasing the intraocular pressure to cut off the blood supply from the retinal artery. Elevated intraocular pressure was maintained for 90 minutes by continuous injection of sterile saline through a needle (32 gauge for rats and 33 gauge for mice) inserted into the anterior chamber of the eyes through the corneas and connected to a hanging saline bag elevated to provide 120 mmHg of pressure head. For the sham-treated group, contralateral eyes were treated by briefly inserting the needle into the anterior chamber of the eye through the cornea. During ischemia, intraocular pressures were monitored using a microtonometer (TonoLab, Icare, Helsinki, Finland) and ranged from 75 to 100 mmHg. Reperfusion occurred naturally after removal of the saline injection needle.

Retinal Imaging and Confocal Microscopy

To image vascular leak in vivo, fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated bovine serum albumin (FITC-BSA, 100 mg/kg body weight) was injected into the femoral vein and allowed to circulate for 10 minutes. After pupil dilation, retinas were imaged using a Micron III (Phoenix Research Laboratories, Pleasanton, CA) for fluorescent angiography. After fundus imaging, eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, retinas were flat mounted, and FITC-BSA was imaged with a Leica DM6000 fluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

Occludin and zonula occludens protein 1 localization in retinal vessels was assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy in whole-mounted retinas, as previously described,20 and analyzed on a Leica TCS SP5 AOBS confocal microscope with Leica Application Suite imaging software version 3. A confocal Z-stack of 10 serial images was collected over a depth of 5 μm and collapsed and projected as one image. Retinal cross sections were stained using primary antibody to complement factor B (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) at a dilution of 1:200 and secondary anti-rabbit Alexa-488 at a dilution of 1:1000.

Spectral Domain–Optical Coherence Tomography

In vivo images of retina and vitreous were obtained using spectral domain–optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Bioptigen, Durham, NC) of anesthetized Long-Evans rats. Rectangular volumes consisting of 1000 A-scans by 100 B-scans over a 2.6 × 2.6-mm area centered on the optic nerve head (ONH) were taken for visualization of retinal anatomy and vitreous bodies. Retinal thicknesses were measured at 500 μm distant from the ONH using an annular scan (1000 A-scans by 3 B-scans by 18 frames) centered on the ONH. Using the InVivoVue Diver Analysis software version 1.0 (Bioptigen), four measurements of total retinal thickness from the top of the retinal ganglion cell layer to the retinal pigment epithelium were obtained in nasal, temporal, superior, and inferior regions of the retina. The four measurements were averaged to generate an average total retinal thickness. For each animal, basal retinal thicknesses were obtained just before conducting experiments and were subtracted from final retinal thicknesses to obtain relative changes from baseline.

Retinal Vascular Permeability

Under anesthesia, animals received a femoral vein injection of FITC-BSA (100 mg/kg body weight for rats or 200 mg/kg body weight for mice). After 2 hours, animals were anesthetized again, and blood samples were collected from the inferior vena cava. The animals were then perfused through the heart with warm saline at physiological pressure (120 mmHg) via the left ventricle for 2 minutes. The retinas were harvested and dried overnight to obtain dry weights for data normalization. FITC-BSA was extracted from retinal tissues using 1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Fluorescence of extracts and plasma samples were measured using a fluorescent plate reader and compared with a standard curve. Retinal FITC-BSA values were normalized to the measured plasma FITC-BSA concentration, the retinal dry weight, and time of dye circulation.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Leukostasis and Leukocyte Infiltration

After euthanasia, mouse eyes were removed, retinas were quickly dissected, and two retinas per sample were pooled for processing. Retinas were processed for flow cytometry, as described previously.31 Retinal cells were suspended in 50 μL of blocking buffer [PBS containing 20% rat serum and 1 μg/mL Mouse Fc-Block (rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32; clone 2.4G2; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA)] and incubated for 20 minutes on ice. The cells were then incubated with PerCP-Cy5.5 conjugated rat anti-mouse CD11b monoclonal antibody (1:100 dilution; clone M1/70; BD Biosciences), APC-Cy7 conjugated rat anti-mouse CD45 monoclonal antibody (1:100 dilution; clone 30-F11; BD Biosciences), phosphatidylethanolamine conjugated rat anti-mouse Ly6C monoclonal antibody (1:100 dilution; clone; HK1.4; eBioscience, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse Ly6G (Gr-1) monoclonal antibody (1:75 dilution; clone RB6-8C5; eBioscience) and incubated for 45 minutes on ice. After rinsing three times in cold PBS, the cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Cells were analyzed using an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). CompBeads (BD Biosciences) anti-mouse Ig microparticle compensation set was incubated with each antibody pair for compensation corrections for spectral overlaps. Cytometer data were analyzed using FlowJo software version 10.4 (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR). To exclude events representing debris and clumps of cells, total events were gated in plots of forward scatter area versus side scatter area and then gated in plots of forward scatter width versus forward scatter area in identical manners for each group before analysis of CD11b, CD45, Ly6C, and Ly6G immunofluorescence intensities. Antigen positivity cutoffs were determined from each maximum autofluorescence of cells incubated without labeled antibody. Cutoffs for Ly6Chi fluorescence values were determined as the minimum LyC6 fluorescence of the granulocyte population in IR samples. Cell population sizes were expressed as number of cells per million events.

Statistical Analysis of Data

All studies were performed in duplicate or triplicate and presented as a compilation of multiple independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software version 7.0a (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) using t-test or one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's or Sidak's post hoc analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of Kinase-Dead PKCζ Blocks IR-Induced Permeability

Previously, expression of a kinase-dead K281W mutant of PKCζ (kdPKCζ) was shown to act in a dominant manner and inhibit VEGF-induced permeability in primary endothelial cell culture.20 The same kdPKCζ mutant cDNA with an HA tag was cloned into a plasmid with the Tek promoter, including a 10-kb enhancer (Figure 1A), and used to generate transgenic mice. A PCR analysis of RNAs isolated from retina, liver, and brain revealed expression of the transgene (Tg) only in the animals genotyped as carrying the kdPKCζ gene and not from noncarrier (NC) mice (Figure 1B). Retinal expression of the HA tag was observed by immunocytochemistry of the Tg+ mice (Figure 1C), and expression of the HA tag was also observed in the brain cortex (Supplemental Figure S1). The immunostaining revealed vascular endothelial–restricted expression, but with incomplete vessel coverage. Furthermore, RT-PCR with primers specific for the kdPKCζ was used to assay RNA isolated from circulating leukocytes. HA-tagged kdPKCζ mRNA was identified in five leukocyte samples from individual kdPKCζ Tg+ mice, but only after cDNA synthesis (Figure 1D). No PCR product was obtained from leukocyte RNA from NC mice, indicating no genomic contamination. Analysis of retinal vasculature revealed that expression of the Tg had no effect on the mature retinal vessel length or branch points, with only a minor, but statistically significant, reduction in vessel density in the superficial layer but not in the deep capillary layer (Supplemental Figure S2). Furthermore, no significant differences in blood pressure or retinal arterial systolic or diastolic blood velocity were observed, as determined by laser Doppler [heart rate (beats per minute): NC, 507 ± 11; kdPKCζ, 514 ± 8; retinal artery velocity systolic (mm/second): NC, 83.01 ± 9.69; kdPKCζ, 74.02 ± 6.65; and diastolic (mm/second): NC, 48.30 ± 5.57; kdPKCζ, 40.92 ± 4.09].

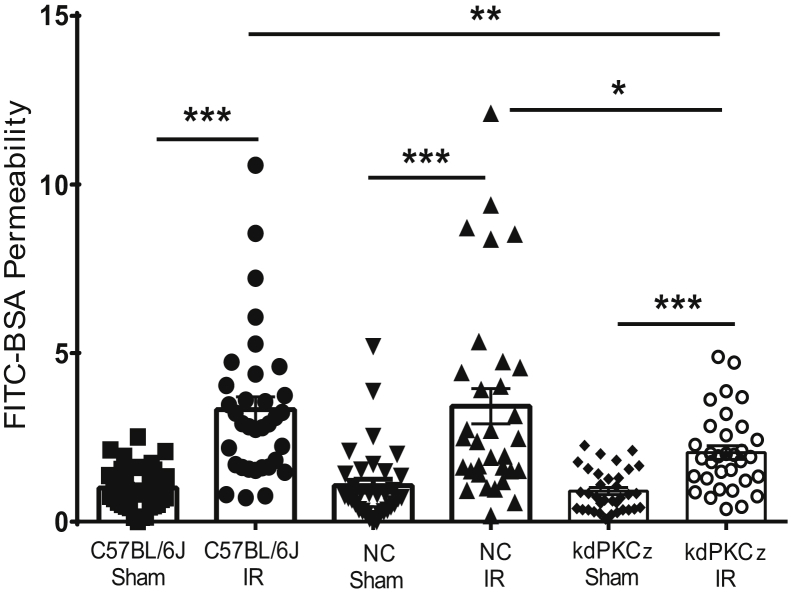

The vascular permeability response was assessed in the kdPKCζ Tg mice using a retinal IR injury model that includes both VEGF-driven permeability and innate, sterile inflammation. Previous studies in rat demonstrated transient retinal ischemia, followed by reperfusion, leads to a dramatic increase in retinal permeability, which can be prevented by delivery of anti-VEGF antibody, and a robust inflammatory reaction observed by chip array analysis at 2 days after injury.31, 32, 33 In the current study, retinal permeability dramatically increased 48 hours after inducing 90 minutes of retinal IR injury in C57BL/6J mice and NC littermates, as assessed by accumulation of i.v. injected FITC-BSA in the retina. However, expression of the kdPKCζ under the Tek promoter significantly prevented approximately half of the IR injury–induced permeability (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Expression of kdPKCζ blocks retinal permeability induced by ischemia-reperfusion (IR). C57BL/6J, kdPKCζ, and noncarrier (NC) mice were subjected to retinal ischemia for 90 minutes in the experimental eye, followed by natural reperfusion or sham needle punctured in the contralateral eye. At 48 hours after IR, fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated bovine serum albumin (FITC-BSA) assay was used to assess retinal vascular permeability. Results are expressed relative to the C57BL/6J-sham. Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Furthermore, the direct effect of VEGF on retinal endothelial permeability was assessed in the kdPKCζ Tg mice. Permeability was assessed 36 hours after intravitreal VEGF injection. The NC littermates revealed a large increase in permeability to FITC-BSA, as expected. The kdPKCζ Tg mice demonstrated an increase in FITC-BSA permeability, but the effect was significantly reduced compared with NC controls (Supplemental Figure S3A). In addition, the change in retinal thickness from baseline after VEGF injection, as measured by spectral domain–OCT, was increased by VEGF in the NC littermates, and this effect was significantly reduced in the kdPKCζ Tg animals (Supplemental Figure S3B). The inhibitory effect on VEGF-induced permeability was less than previously observed using a small-molecule aPKC inhibitor20 and may be attributable to only partial penetrance of Tek-driven kdPKCζ expression in the adult mouse retinal vasculature.

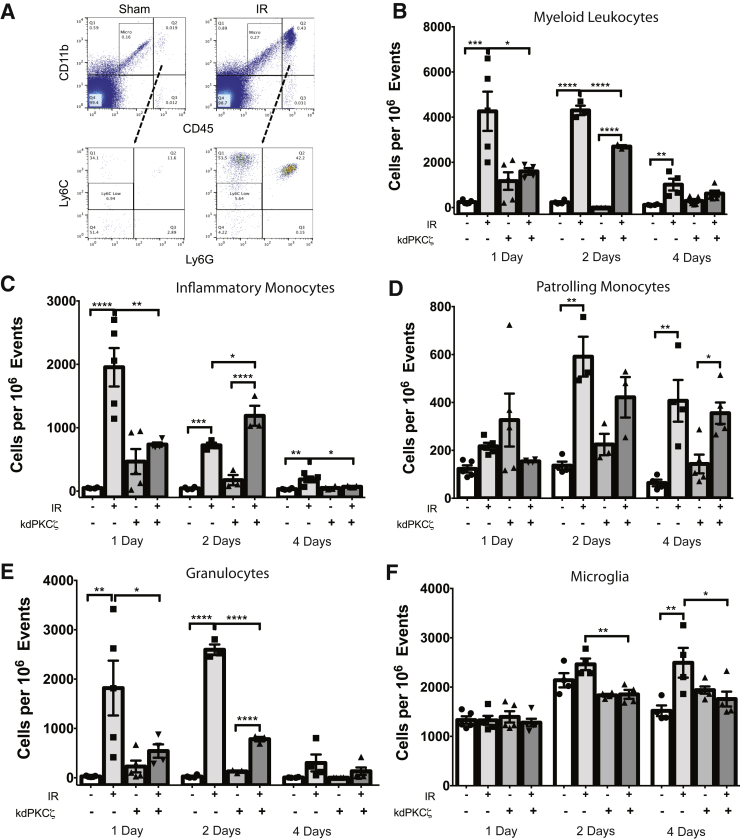

kdPKCζ Tg Expression Reduces IR-Induced Inflammation

The effect of expressing the kdPKCζ transgene under the Tek promoter on inflammation in the retina was next examined. Mice expressing the Tg were compared with NC littermates after a 90-minute ischemia event, followed by reperfusion for 1, 2, or 4 days. Retinas were collected, pooled, and prepared for immunofluorescence flow cytometry analysis to quantify microglia (CD45low/CD11b+/Ly6Gneg/Ly6Cneg) and myeloid leukocytes (CD45hi/CD11b+). The myeloid leukocyte population was further characterized as granulocytes (CD45hi/CD11b+/Ly6G+), inflammatory monocytes (CD45hi/CD11b+/Ly6Gneg/Ly6Chi), and reparative monocytes (CD45hi/CD11b+/Ly6Gneg/Ly6Cneg) (Figure 3A). This analysis revealed that IR induced a dramatic increase in myeloid leukocytes at 1 and 2 days after injury that was largely diminished by 4 days (Figure 3B). Inflammatory monocytes (Figure 3C) and granulocytes (Figure 3E) accounted for the largest portion of the invading myeloid leukocytes. Expression of the mutant kdPKCζ Tg dramatically reduced the IR-induced increase in myeloid leukocytes at both 1 and 2 days (Figure 3B). Compared with NC-IR controls, expression of the kdPKCζ Tg significantly decreased inflammatory monocyte numbers on day 1 (Figure 3C) and granulocyte numbers on both days 1 and 2 (Figure 3E). By day 4, the numbers of inflammatory monocytes and granulocytes were largely returned to normal; however, a significantly increased population of Ly6Chi inflammatory monocytes remained in injured retinas of NC control retinas but not in the retinas of kdPKCζ Tg animals. Interestingly, the Ly6Cneg reparative monocytes, also referred to as patrolling monocytes,34 exhibited a delayed increase after injury and remained elevated at day 4, with no significant differences in retinas of NC and kdPKCζ Tg animals (Figure 3D). In addition, the microglia population expanded over the 4-day time course in the noncarrier littermates, but this increase was prevented in the kdPKCζ Tg animals (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Expression of kdPKCζ reduces ischemia-reperfusion (IR)–induced inflammation. Noncarrier and kdPKCζ mice were subjected to IR injury. At 1, 2, and 4 days after IR injury, retina samples were harvested for flow cytometry to quantify leukocytes: sample scatter gram (A), myeloid leukocytes (B), Ly6C high inflammatory monocytes (C), Ly6C-negative patrolling monocytes (D), granulocytes (E), and microglia (F). Treatment groups were compared within each day by analysis of variance, followed by Sidak's post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

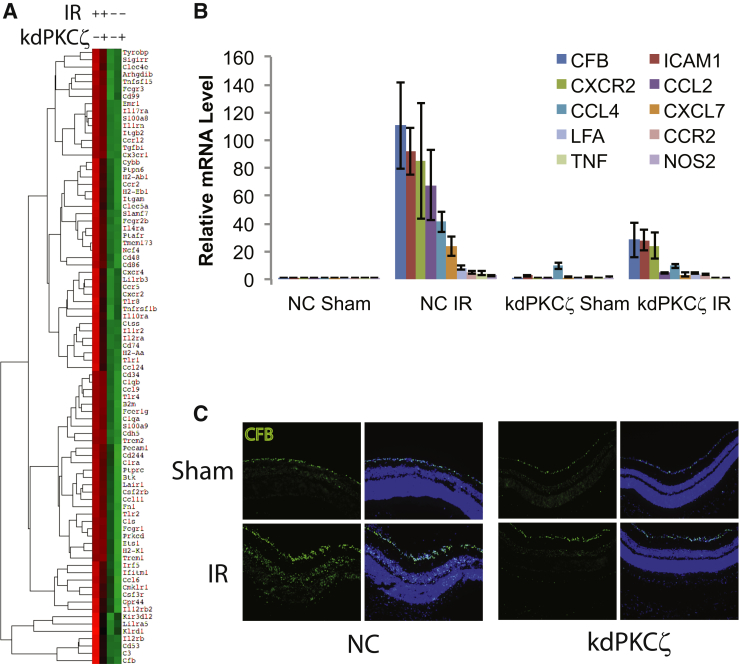

The mRNA of inflammatory factors was analyzed by the nCounter Analysis System (NanoString Technologies) using an Immunology v2 kit to simultaneously probe for expression of >500 genes related to the immune system. RNA was isolated 48 hours after IR, and three replicates of NC littermates and three kdPKCζ Tg mice, each with sham and IR retinas, were analyzed. Normalization was done using three housekeeping genes, including TATA-box–binding protein, ribosomal protein L19, and eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 γ. A heat map was generated using euclidian distance metric and centroid linkage method (Figure 4A). The heat map reveals that expression of the kdPKCζ Tg attenuated expression of most inflammatory genes that normally increased after IR injury. The difference between IR/sham expression ratios in NC controls and kdPKCζ Tg mice allowed us to identify genes whose IR-induced expression was highly attenuated by kdPKCζ. Expression of selected mRNAs was then examined by quantitative RT-PCR, from separate samples, confirming the nanoString analysis (Figure 4B and Supplemental Table S1). This analysis identified inflammatory genes elevated in response to IR in an aPKC-dependent manner and included the following: complement factor B (CFB); inflammatory factors, such as TNFα and NOS2; the chemokines [C-C motif ligand (CCL) or receptor CCR and C-X-C motif ligand (CXCL) or receptor (CXCR)]; CCL2, CCL4, CXCL7, CCR2, and CXCR2; and intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) and its binding partner lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA). CFB mRNA demonstrated >100-fold increase in expression after IR in the NC animals, which was attenuated by nearly 75% in the kdPKCζ Tg animals, one of the largest inhibitions observed. Immunostaining of retinal cross sections for CFB revealed an increase in protein in response to IR that was also attenuated in the kdPKCζ Tg–expressing animals (Figure 4C). Interestingly, this analysis also identified mRNA of a single gene, CCL8, which was significantly induced by IR injury in retinas of kdPKCζ Tg mice more than in NC controls (data not shown). Collectively, the inflammatory cell analysis and gene expression analysis revealed that expression of kdPKCζ Tg reduced the expression of inflammatory cytokines involved in recruiting leukocytes, reduced inflammatory monocyte and granulocyte recruitment, and inhibited microglial expansion after retinal IR injury.

Figure 4.

Expression of kdPKCζ attenuates ischemia-reperfusion (IR)–induced inflammation. Noncarrier (NC) and kdPKCζ mice were subjected to IR injury. At 48 hours after IR, retina samples were harvested for RNA isolation, followed by mRNA quantification by nCounter Analysis System using Immunology v2 kit. A: Heat map represents expression level from low (green) to high (red). B: Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA profile of various proinflammatory cytokines from a separate IR experiment with sample collection at 48 hours after injury. Every gene shown represents an increase after IR in the NC animals, which was significantly attenuated by expression of kdPKCζ, as determined by analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test. Data table and statistics are shown in Supplemental Table S1. C: Immunofluorescence staining of retinal cross section for CFB (green) and nuclei (blue) 48 hours after IR. Original magnification, ×200 (C). CCL, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; CFB, complement factor B; CXCR, C-X-C chemokine receptor; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; LFA, lymphocyte function-associated antigen; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

aPKC Inhibitor Blocks IR-Induced Permeability

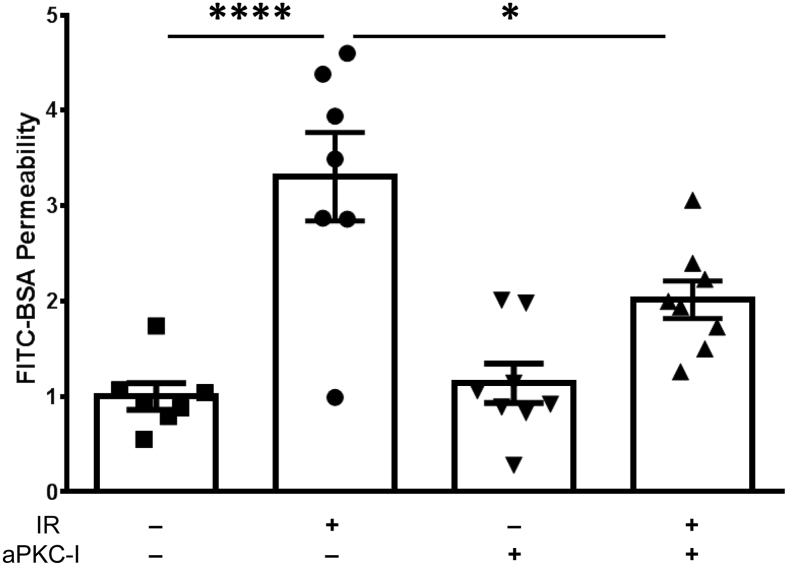

To further explore the role of aPKC in control of retinal permeability after IR injury, the aPKC inhibitor ethyl 2-amino-4-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-thiophenecarboxylate was tested. This drug was previously shown to inhibit both PKCζ and PKCι with high specificity and to prevent VEGF-induced endothelial permeability in cell culture and in vivo.19, 20 The IR model was used to test the effectiveness of local aPKC inhibitor delivery on the permeability response. The aPKC inhibitor, delivered at an estimated intravitreal concentration of 1 μmol/L, effectively reduced IR-induced permeability of FITC-BSA at 24 hours (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

aPKC inhibitor blocks ischemia-reperfusion (IR)–induced permeability. Rats were injected intravitreally with vehicle [0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline] or 1 μmol/L of aPKC inhibitor (aPKC-I) at 30 minutes before IR injury. At 24 hours after IR, animals received another intravitreal injection of vehicle or aPKC-I. Fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated (FITC) BSA (100 mg/kg body weight) was injected 30 minutes later and allowed to circulate for 2 hours, and the retinal dye accumulation was determined as a measure of vascular permeability. Results are expressed relative to the vehicle-sham. Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Intravitreal VEGF and TNF-α Induces Retinal Edema and Inflammation

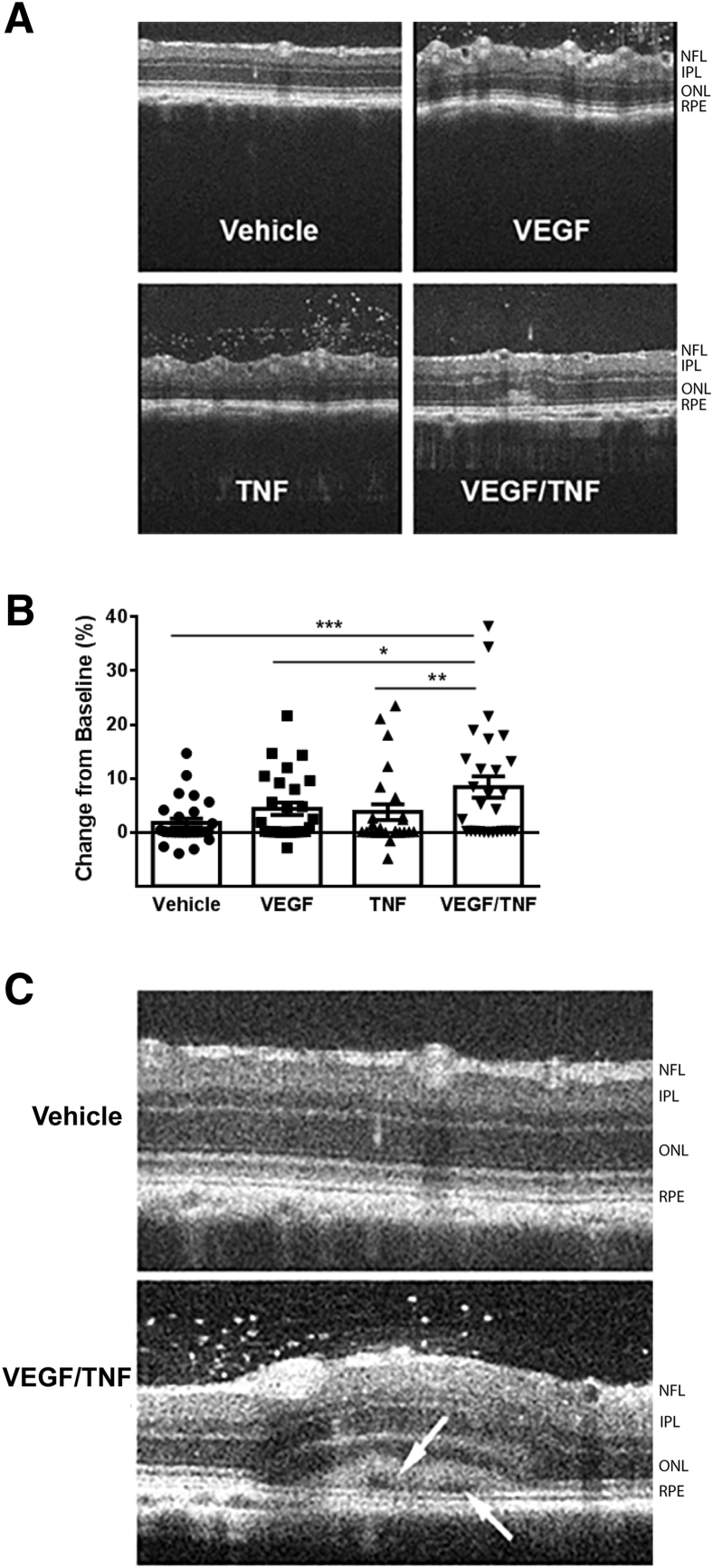

On the basis of the results of the genetic inhibition of aPKC in ischemia-reperfusion, a second model of retinal inflammation was developed to test the effectiveness of the aPKC inhibitor on retinal vascular permeability. Intravitreal coinjection of the growth factor VEGF (50 ng) along with the inflammatory initiator TNF-α (10 ng), identified as elevated in IR, was sufficient to recapitulate the changes in retinal permeability and innate immune responses observed in IR. Intravitreal coinjection of VEGF and TNF-α led to edema at 24 hours, as observed by retinal thickening in OCT analysis of annular scans taken at 500 μm from the ONH (Figure 6A). This response was maximal at 24 hours and slowly resolved over 4 weeks (data not shown). Measures of retinal thickness at baseline and after VEGF/TNF-α injection were taken at four positions around the ONH and averaged for each eye. The difference in retinal thickness from baseline for each eye demonstrates a clear increase in retinal edema in VEGF/TNF-injected condition (Figure 6B). Furthermore, on occasion, cystoid space formation was observed near the retinal pigment epithelium only in VEGF/TNF-injected eyes (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Intravitreal injection of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) increases retinal thickness. Rats were intravitreally injected with vehicle (0.1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline), VEGF (50 ng), TNF (10 ng), or a combination of VEGF/TNF (50/10 ng, respectively). Retinal thickness was assessed with spectral domain–optical coherence tomography after 24 hours. A: Representative annular scan images at 500 μm from the optic nerve head. B: Retinal thickness quantification from the annular scan as the change in retinal thickness 24 hours after injection relative to baseline scan, analyzed by analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test. C: Example of VEGF/TNF injection leading to subretinal fluid accumulation and retinal detachment. Arrows indicate cystoid space formation observed near the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Data are expressed as means ± SEM (B). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. IPL, inner plexiform layer; NFL, nerve fiber layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer.

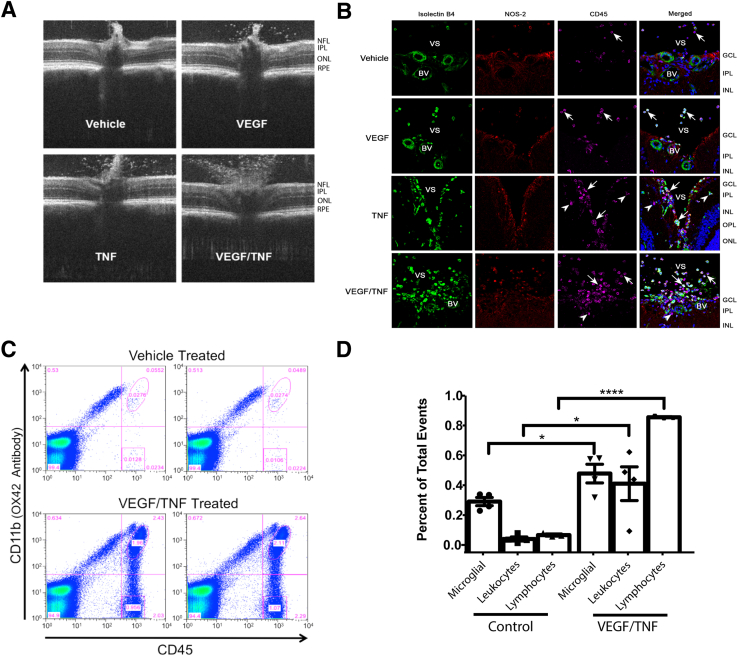

Intravitreal VEGF and TNF-α injection also induced a vitritis that emanated from the ONH. Representative OCT B-scan images centered at the ONH at 24 hours after intravitreal injection of vehicle control, VEGF, TNF-α, or VEGF plus TNF-α are shown in Figure 7A. These images reveal a robust increase in vitreous hyperreflective foci after either VEGF or TNF-α injection, and particularly after VEGF/TNF-α coinjection. These hyperreflective foci in the vitreous have been identified by OCT imaging in patients with diabetic retinopathy.35 To determine whether these foci represent an inflammatory response, retinal cross sections close to the ONH were analyzed for the presence of bone marrow–derived leukocytes by immunofluorescence staining with isolectin B4, CD45, and NOS2 (Figure 7B). IB4 is a lectin that stains both vascular endothelium and bone marrow–derived cells, CD45 is the leukocyte common antigen, and NOS2 is inducible NOS expressed in active inflammatory cells, such as macrophages. A dramatic increase in isolectin B4–, NOS2-, and CD45-positive leukocytes emanating from the optic disk was observed in the retina and vitreous of VEGF/TNF-α–treated retinas. Flow cytometry analysis of microglia (CD45low/CD11b+), myeloid leukocytes (CD45hi/CD11b+), and lymphocytes (CD45hi/CD11bneg) was performed on retinas. VEGF/TNF-α treatment significantly increased the retinal populations of all three of these inflammatory cell types (Figure 7, C and D).

Figure 7.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–induced retinal inflammation. Rats were intravitreally injected with vehicle (0.1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline) or VEGF/TNF (50/ng). A: Optical coherence tomography scan above the optic nerve head reveals increased hyperreflective foci in the vitreous 24 hours after VEGF/TNF coinjection. B: Immunostaining for isolectin B4 (green), NOS2 (red), and CD45 (far red) reveals leukocyte infiltration 24 hours after VEGF/TNF injection. Arrows indicate leukocytes in the vitreous space (VS). Arrowheads indicate infiltrated leukocytes in the retina and the blood vessels (BVs). C: Example of duplicate scatter grams at 24 hours after intravitreal injection of VEGF/TNF; retinal leukocytes were quantified by flow analysis and compared with controls. D: Quantification of flow cytometry of microglia, myeloid leukocytes, and lymphocytes, and analyzed by t-test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. Original magnification, ×630 (B). GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; NFL, nerve fiber layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

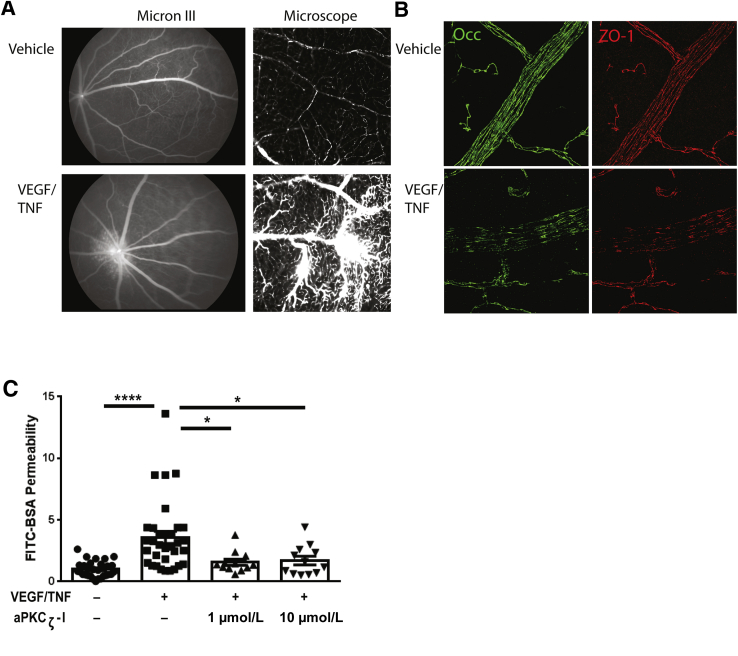

VEGF/TNF-α coinjection also altered vascular barrier properties and the tight junction complex. FITC-BSA was delivered by i.v. injection 5 hours after VEGF/TNF-α intravitreal injection. Micron III images revealed a large diffuse region of vascular permeability surrounding the ONH (Figure 8A), similar to that observed in patients with inflammatory eye disease, such as posterior uveitis, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, or intraretinal microvascular abnormalities. After fundus examination, retinas were removed, whole mounted, and microscopically examined for the FITC-BSA leakage. Regions of capillary and arteriole leak were readily apparent (Figure 8A). Immunofluorescence staining of tight junction proteins occludin and zonula occludens protein 1 clearly revealed reduced staining at the endothelial cell border after VEGF/TNF-α injection compared with control (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/tumor necrosis factor (TNF) induces retinal permeability and tight junction loss at the cell border. Rats were injected intravitreally with vehicle [0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] or VEGF/TNF (50/10 ng). A: Fluorescent angiography using Micron III was performed at 5 hours after intravitreal cytokine injection, followed by intravenous injection of fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated (FITC) BSA (100 mg/kg body weight) and 10-minute circulation. Generally increased retinal fluorescence, with clear changes at the optic nerve head, is readily observed (Micron III). After angiography, retinas were dissected and flat mounted for microscopic visualization, where vascular leak from capillaries was readily observed (microscope). B: Flat-mount retinas were analyzed for immunoreactivity of occludin (Occ) and zonula occludens protein 1 (ZO-1). Loss of occludin and ZO-1 immunostaining at endothelial cell borders was observed in the VEGF/TNF-treated retinas. C: aPKCζ inhibitor (aPKCζ-I) blocks VEGF/TNF-induced permeability. Rats were intravitreally injected with vehicle (0.1% BSA in PBS), VEGF/TNF (50/10 ng), or indicated dose of aPKCζ-I in combination with VEGF/TNF. At 3 hours after intravitreal injection, animals received an i.v. injection of FITC-BSA (100 mg/kg body weight). Two hours later, animals were perfused with warm saline and retinas were removed for quantification of FITC-BSA accumulation. Results are expressed relative to vehicle control. Differences between groups were analyzed by analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (C). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. Original magnification, ×630 (A, right column, and B).

Finally, the small-molecule aPKC inhibitor was tested for its efficacy in attenuating retinal permeability induced by VEGF/TNF-α treatment. Coinjection of VEGF/TNF-α plus aPKC inhibitor dramatically reduced the increase in FITC-BSA accumulation measured after 2 hours of dye circulation, beginning at 3 hours after VEGF/TNF-α injection (Figure 8C).

Discussion

Inflammation and inflammatory cytokines may contribute to changes in retinal vascular permeability in a host of blinding eye diseases, including diabetic retinopathy, uveitis, and ischemic retinopathies. In particular, the individual contribution of VEGF and TNF-α to pathologic retinal edema and inflammation are well documented. VEGF and TNF-α possess distinct signaling mechanisms that act to induce retinal endothelial vascular permeability. VEGF activates classic PKC isoforms that phosphorylate the tight junction protein occludin, leading to its ubiquitination and subsequent internalization, and promotes internalization of other tight junction proteins, thereby inducing paracellular gaps and increased retinal vascular permeability.16 Conversely, TNF-α induces an NF-κB–dependent repression of transcription of the genes for the tight junction proteins claudin 5 and zonula occludens protein 1.18 However, both VEGF- and TNF-α–induced permeability require aPKC signaling to induce endothelial permeability.20 Furthermore, others have suggested aPKC isoforms mediate signaling from other permeabilizing agents, including thrombin27 and CCL2.28 Therefore, aPKC is a potential target to control vascular permeability caused by a variety of cytokines.

In the current study, we used both genetic and small-molecule inhibition of aPKC to reduce retinal vascular permeability in two models of ocular inflammation. Expression of a kinase-dead form of PKCζ under the Tek promoter reduced vascular permeability in a model of ischemia-induced retinal inflammation. PCR analysis also confirmed transgene expression in bone marrow–derived circulating leukocytes, consistent with previous observation of Tek-driven Cre expression inducing marker genes in 85% of adult bone marrow and spleen.36 However, expression of the Tek gene product Tie2 is much lower in adult circulating leukocytes. Interestingly, expression of the kdPKCζ under the Tek promoter, which has robust developmental expression, did not induce any observed developmental abnormalities in the mice or cause a difference in expected mendelian inheritance ratio (data not shown). This is dramatically different from Prkci gene deletion, which leads to embryonic lethality,22 and suggests endothelial cells do not have the same requirement for polarity during development as epithelial cells.

Expression of kdPKCζ dramatically reduced permeability in the IR injury model of inflammation and significantly reduced the numbers of both inflammatory monocytes and granulocytes recruited to the retina. The effect of the kdPKCζ Tg on permeability likely involves a direct endothelial cell effect on cytokine-induced permeability, because previous studies in endothelial cell culture reveal a requirement for aPKC activity in both VEGF-induced20 and TNF-α−induced18 permeability. Herein, the kdPKCζ Tg reduced direct VEGF injection–induced permeability (Supplemental Figure S3). The incomplete inhibition of IR- or VEGF-induced permeability may be attributable to the limited penetrance of the kdPKCζ Tg in the adult retinal vasculature under the Tek promoter, but may also reflect contributions of other signaling pathways in vascular permeability, such as conventional PKC signaling.16

Expression of kdPKCζ Tg also led to a significant inhibition of inflammation after IR compared with the noncarrier littermates, as observed by flow cytometry analysis and reduced expression of several mRNAs corresponding to inflammatory factors. These factors included the following: NOS2 found in inflammatory cells; cytokines involved in induction of inflammation, such as TNF-α; chemokines that recruit monocytes, such as CCL2 and CCL4; and granulocyte chemoattractants, such as CXCL7. IR-induced increases in mRNAs for chemokine receptors characteristic of macrophages (CCR2) and neutrophils (C-X-C chemokine receptor 2) were also reduced by expression of kdPKCζ Tg. In addition, kdPKCζ Tg reduced IR-induced expression of the adhesion molecule ICAM1 and its binding partner LFA. More important, ICAM1 gene deletion was found previously to reduce leukocyte adhesion and measures of retinopathy in two models of diabetes.37 Finally, CFB was dramatically up-regulated by IR, and this was largely inhibited by expression of the kdPKCζ Tg, as observed by mRNA quantification and immunofluorescence staining of retinal cross sections.

The anti-inflammatory effect of expressing kdPKCζ is consistent with previous studies demonstrating a role for aPKC, and PKCζ specifically, in regulating NF-κB activity and signal transduction in response to a variety of inflammatory stimuli. Previous publications revealed that the inflammatory responses in both endothelial cells and macrophages require aPKC activity. aPKCζ deletion severely impairs NF-κB–dependent gene transcription stimulated by either TNF-α or IL-1β.21 PKCζ is required for ICAM1 phosphorylation and leukocyte binding in response to TNF-α.25 aPKC contributes to macrophage activation and NOS2 expression in experimentally induced uveitis.26 An aPKCζ inhibitor or a dominant-negative aPKC mutant blocked both NF-κB and transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) kinase activation in monocytes/macrophages in response to lipopolysaccharide.38 Toll-like receptor 4 or TNF-α receptor activation promotes PKCζ translocation to the plasma membrane by the ezrin-radixin-moesin–binding phosphoprotein 50, which is necessary for NF-κB activation in macrophages and vascular cells; deletion of ezrin-radixin-moesin–binding phosphoprotein 50 prevents macrophage recruitment to vascular lesions.39 Therefore, the data from the Tie2/kdPKCζ mice are consistent with expression of kdPKCζ in endothelial cells directly inhibiting vascular permeability, whereas expression in both leukocytes and endothelial cells may inhibit leukocyte recruitment and activation. In particular, inflammatory monocyte and granulocyte recruitment was decreased and microglial proliferation was inhibited. Future studies using endothelial-, leukocyte-, and microglial-specific expression of kdPKCζ expression may delineate the specific requirement of aPKC signaling in each cell type.

Previous studies in our laboratory have demonstrated the activation of aPKC in response to VEGF and have shown that inhibition of aPKC with kdPKCζ, siRNA, or small-molecule inhibitors can prevent VEGF-induced endothelial permeability.19, 20 One of these small-molecule inhibitors was used herein to significantly reduce IR-induced endothelial permeability when injected intravitreally. Furthermore, two factors were identified that together were sufficient to recapitulate the changes in sterile inflammation and retinal permeability. Coinjection of TNF-α and VEGF induced a robust inflammatory response and retinal vascular permeability. The coinjection of an inflammatory cytokine along with the permeabilizing agent VEGF may model aspects of diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusions, and uveitis, in which dramatic changes to vascular permeability may occur, thus inducing macular edema and inflammation. Coinjection of the small-molecule aPKC inhibitor blocked vascular permeability induced by the VEGF/TNF-α coinjection. These studies are consistent with the use of a small peptide for inhibition of aPKC that reduced retinal inflammation in a rat model of endotoxin-induced uveitis.26

In conclusion, conditional genetic expression of kdPKCζ prevented IR-induced retinal vascular permeability and the innate immune response; particularly, inflammatory monocyte and granulocyte recruitment to the retina and microglial proliferation were repressed. The inhibition of vascular permeability was further demonstrated using a small-molecule inhibitor of aPKC. Furthermore, VEGF and TNF-α coinjection recapitulated the vascular permeability and inflammatory response observed in the IR model, and permeability was again attenuated with a small-molecule inhibitor of aPKC. These studies support a role for aPKC as a common signaling molecule in the control of vascular permeability by both growth factors and inflammatory cytokines, as well as a role in recruitment of inflammatory monocytes, granulocytes, and microglial expansion. Ongoing studies are focused on identifying downstream targets of aPKC that mediate the control of vascular permeability. The current preclinical studies suggest targeting aPKC may provide a clinically important therapeutic means to reduce retinal vascular permeability and ocular inflammation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Heather Hager and Alyssa Dreffs for preparing experimental animals, Sumathi Shanmugam and Dr. Arivalagan Muthusamy for technical assistance, and Dr. Thomas N. Sato (Advanced Telecommunications Research Institute International, Kyoto, Japan) for providing transgenic atypical protein kinase C mice.

Footnotes

See related commentary on page 2142

Supported by NIH grants R01 EY012021 (D.A.A.), R01 EY023725 (D.A.A.), and R24 EY024868 (D.A.A. and S.F.A.), Research to Prevent Blindness grants (D.A.A.), and JDRF grants (D.A.A.). This work used the Vision Research Core at the Kellogg Eye Center, funded by National Eye Institute grant P30 EY007003 and Morphology and Image Analysis Core of the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center grant P30 DK020572.

C.-m.L. and P.M.T. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.06.020.

Supplemental Data

Immunofluorescence staining of kdPKCζ in brain. Brain sections from noncarrier (NC) or kdPKCζ mice were stained for CD31 (green), hemagglutinin (HA) tag (red), or nuclei (blue). HA-tag staining of brain vessels is readily apparent in kdPKCζ but not NC animals. No primary antibody control also shown. Arrowheads indicate expression of kdPKCζ. Ab, antibody.

Expression of kdPKCζ does not alter vascular pattern. Whole-mount retinas were stained with isolectin B4, and images were quantified for vascular branch points, vessel length, or vessel density in both the ganglion cell layer and the deep capillary plexus. ∗P < 0.05. NC, noncarrier.

Expression of kdPKCζ blocks retinal permeability induced by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). A: Noncarrier (NC) and kdPKCζ mice received intravitreal injection of 200 ng mouse VEGF in one eye and vehicle [0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline] in the other eye. At 36 hours after injection, fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated (FITC) BSA (200 mg/kg body weight) was injected intravenously to assess retinal permeability. Results are expressed relative to the NC-vehicle. B: Optical coherence tomography images were obtained before intravitreal injection (baseline) and at 36 hours after injection. Total retinal thickness was measured using a volume scan at 350 μm from the optic nerve head. Measurements of superior, inferior, temporal, and nasal retinal thickness for each retina were performed to calculate the change in total retinal thickness from baseline. Change from baseline was presented. Statistical analysis by analysis of variance, followed by Tukey post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (A and B). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

References

- 1.Campochiaro P.A. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for retinal vein occlusions. Ophthalmologica. 2012;227 Suppl 1:30–35. doi: 10.1159/000337157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emerson M.V., Lauer A.K. Emerging therapies for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema. BioDrugs. 2007;21:245–257. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200721040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markomichelakis N.N., Theodossiadis P.G., Pantelia E., Papaefthimiou S., Theodossiadis G.P., Sfikakis P.P. Infliximab for chronic cystoid macular edema associated with uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:648–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonetti D.A., Klein R., Gardner T.W. Diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1227–1239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1005073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson M.W. Etiology and treatment of macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:11–21.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knudsen L., Lervang H., Lundbye-Christensen S., Gorst-Rasmussen A. The North Jutland County Diabetic Retinopathy Study population characteristics. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1404–1409. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.093393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein R., Klein B.E.K., Moss S.E., Cruscishanks K.J. The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy, XV: the long-term incidence of macular edema. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)31052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen Q.D., Brown D.M., Marcus D.M., Boyer D.S., Patel S., Feiner L., Gibson A., Sy J., Rundle A.C., Hopkins J.J., Rubio R.G., Ehrlich J.S. Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: results from 2 phase III randomized trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bressler S.B., Liu D., Glassman A.R., Blodi B.A., Castellarin A.A., Jampol L.M., Kaufman P.L., Melia M., Singh H., Wells J.A., Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Change in diabetic retinopathy through 2 years: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial comparing aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:558–568. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.0821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai S., Bressler N.M. Aflibercept, bevacizumab or ranibizumab for diabetic macular oedema: recent clinically relevant findings from DRCR.net Protocol T. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017;28:636–643. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang H., Gandhi J.K., Zhong X., Wei Y., Gong J., Duh E.J., Vinores S.A. TNFalpha is required for late BRB breakdown in diabetic retinopathy, and its inhibition prevents leukostasis and protects vessels and neurons from apoptosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1336–1344. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arita R., Nakao S., Kita T., Kawahara S., Asato R., Yoshida S., Enaida H., Hafezi-Moghadam A., Ishibashi T. A key role for ROCK in TNF-alpha-mediated diabetic microvascular damage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:2373–2383. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adamis A.P., Berman A.J. Immunological mechanisms in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Semin Immunopathol. 2008;30:65–84. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arias L., Caminal J.M., Badia M.B., Rubio M.J., Catala J., Pujol O. Intravitreal infliximab in patients with macular degeneration who are nonresponders to antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy. Retina. 2010;30:1601–1608. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181e9f942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sfikakis P.P., Grigoropoulos V., Emfietzoglou I., Theodossiadis G., Tentolouris N., Delicha E., Katsiari C., Alexiadou K., Hatziagelaki E., Theodossiadis P.G. Infliximab for diabetic macular edema refractory to laser photocoagulation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover, 32-week study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1523–1528. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murakami T., Frey T., Lin C., Antonetti D.A. Protein kinase cbeta phosphorylates occludin regulating tight junction trafficking in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced permeability in vivo. Diabetes. 2012;61:1573–1583. doi: 10.2337/db11-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakami T., Felinski E.A., Antonetti D.A. Occludin phosphorylation and ubiquitination regulate tight junction trafficking and vascular endothelial growth factor-induced permeability. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21036–21046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aveleira C.A., Lin C.M., Abcouwer S.F., Ambrosio A.F., Antonetti D.A. TNF-alpha signals through PKCzeta/NF-kappaB to alter the tight junction complex and increase retinal endothelial cell permeability. Diabetes. 2010;59:2872–2882. doi: 10.2337/db09-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Titchenell P.M., Hollis Showalter H.D., Pons J.F., Barber A.J., Jin Y., Antonetti D.A. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 2-amino-3-carboxy-4-phenylthiophenes as novel atypical protein kinase C inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:3034–3038. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Titchenell P.M., Lin C.M., Keil J.M., Sundstrom J.M., Smith C.D., Antonetti D.A. Novel atypical PKC inhibitors prevent vascular endothelial growth factor-induced blood-retinal barrier dysfunction. Biochem J. 2012;446:455–467. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leitges M., Sanz L., Martin P., Duran A., Braun U., Garcia J.F., Camacho F., Diaz-Meco M.T., Rennert P.D., Moscat J. Targeted disruption of the zetaPKC gene results in the impairment of the NF-kappaB pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;8:771–780. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moscat J., Rennert P., Diaz-Meco M.T. PKCzeta at the crossroad of NF-kappaB and Jak1/Stat6 signaling pathways. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:702–711. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki A., Yamanaka T., Hirose T., Manabe N., Mizuno K., Shimizu M., Akimoto K., Izumi Y., Ohnishi T., Ohno S. Atypical protein kinase C is involved in the evolutionarily conserved par protein complex and plays a critical role in establishing epithelia-specific junctional structures. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:1183–1196. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.6.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinberg S.F. Structural basis of protein kinase C isoform function. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1341–1378. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Javaid K., Rahman A., Anwar K.N., Frey R.S., Minshall R.D., Malik A.B. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces early-onset endothelial adhesivity by protein kinase Czeta-dependent activation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Circ Res. 2003;92:1089–1097. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000072971.88704.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Kozak Y., Omri B., Smith J.R., Naud M.C., Thillaye-Goldenberg B., Crisanti P. Protein kinase Czeta (PKCzeta) regulates ocular inflammation and apoptosis in endotoxin-induced uveitis (EIU): signaling molecules involved in EIU resolution by PKCzeta inhibitor and interleukin-13. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1241–1257. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minshall R.D., Vandenbroucke E.E., Holinstat M., Place A.T., Tiruppathi C., Vogel S.M., van Nieuw Amerongen G.P., Mehta D., Malik A.B. Role of protein kinase Czeta in thrombin-induced RhoA activation and inter-endothelial gap formation of human dermal microvessel endothelial cell monolayers. Microvasc Res. 2010;80:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimitrijevic O.B., Stamatovic S.M., Keep R.F., Andjelkovic A.V. Effects of the chemokine CCL2 on blood-brain barrier permeability during ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:797–810. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vasavada R.C., Wang L., Fujinaka Y., Takane K.K., Rosa T.C., Mellado-Gil J.M., Friedman P.A., Garcia-Ocana A. Protein kinase C-zeta activation markedly enhances beta-cell proliferation: an essential role in growth factor mediated beta-cell mitogenesis. Diabetes. 2007;56:2732–2743. doi: 10.2337/db07-0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlaeger T.M., Bartunkova S., Lawitts J.A., Teichmann G., Risau W., Deutsch U., Sato T.N. Uniform vascular-endothelial-cell-specific gene expression in both embryonic and adult transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3058–3063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abcouwer S.F., Lin C.M., Shanmugam S., Muthusamy A., Barber A.J., Antonetti D.A. Minocycline prevents retinal inflammation and vascular permeability following ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:149. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abcouwer S.F., Lin C.M., Wolpert E.B., Shanmugam S., Schaefer E.W., Freeman W.M., Barber A.J., Antonetti D.A. Effects of ischemic preconditioning and bevacizumab on apoptosis and vascular permeability following retinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:5920–5933. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muthusamy A., Lin C.M., Shanmugam S., Lindner H.M., Abcouwer S.F., Antonetti D.A. Ischemia-reperfusion injury induces occludin phosphorylation/ubiquitination and retinal vascular permeability in a VEGFR-2-dependent manner. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:522–531. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas G., Tacke R., Hedrick C.C., Hanna R.N. Nonclassical patrolling monocyte function in the vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1306–1316. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korot E., Comer G., Steffens T., Antonetti D.A. Algorithm for the measure of vitreous hyperreflective foci in optical coherence tomographic scans of patients with diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:15–20. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang Y., Harrington A., Yang X., Friesel R.E., Liaw L. The contribution of the Tie2+ lineage to primitive and definitive hematopoietic cells. Genesis. 2010;48:563–567. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joussen A.M., Poulaki V., Le M.L., Koizumi K., Esser C., Janicki H., Schraermeyer U., Kociok N., Fauser S., Kirchhof B., Kern T.S., Adamis A.P. A central role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. FASEB J. 2004;18:1450–1452. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1476fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang X., Chen L.Y., Doerner A.M., Pan W.W., Smith L., Huang S., Papadimos T.J., Pan Z.K. An atypical protein kinase C (PKC zeta) plays a critical role in lipopolysaccharide-activated NF-kappa B in human peripheral blood monocytes and macrophages. J Immunol. 2009;182:5810–5815. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leslie K.L., Song G.J., Barrick S., Wehbi V.L., Vilardaga J.P., Bauer P.M., Bisello A. Ezrin-radixin-moesin-binding phosphoprotein 50 (EBP50) and nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB): a feed-forward loop for systemic and vascular inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:36426–36436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.483339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Immunofluorescence staining of kdPKCζ in brain. Brain sections from noncarrier (NC) or kdPKCζ mice were stained for CD31 (green), hemagglutinin (HA) tag (red), or nuclei (blue). HA-tag staining of brain vessels is readily apparent in kdPKCζ but not NC animals. No primary antibody control also shown. Arrowheads indicate expression of kdPKCζ. Ab, antibody.

Expression of kdPKCζ does not alter vascular pattern. Whole-mount retinas were stained with isolectin B4, and images were quantified for vascular branch points, vessel length, or vessel density in both the ganglion cell layer and the deep capillary plexus. ∗P < 0.05. NC, noncarrier.

Expression of kdPKCζ blocks retinal permeability induced by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). A: Noncarrier (NC) and kdPKCζ mice received intravitreal injection of 200 ng mouse VEGF in one eye and vehicle [0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline] in the other eye. At 36 hours after injection, fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated (FITC) BSA (200 mg/kg body weight) was injected intravenously to assess retinal permeability. Results are expressed relative to the NC-vehicle. B: Optical coherence tomography images were obtained before intravitreal injection (baseline) and at 36 hours after injection. Total retinal thickness was measured using a volume scan at 350 μm from the optic nerve head. Measurements of superior, inferior, temporal, and nasal retinal thickness for each retina were performed to calculate the change in total retinal thickness from baseline. Change from baseline was presented. Statistical analysis by analysis of variance, followed by Tukey post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (A and B). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.