Abstract

Background

Although mounting non-hereditary colorectal cancer (NHCRC) associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been observed, no field synopsis and meta-analysis has been conducted through systematically assessing cumulative evidence, during the past 5 years.

Methods

We retrieved the database via the PubMed, Web of Science and Embase gateways to identify publications concerning the associations between SNPs and risk of NHCRC, up to May 1st, 2017. To assess the finding credibility, cumulative evidence was graded based on the Venice criteria. Meta-analysis was also performed for three subgroups including ethnicity (Asian vs Caucasian), primary cancer site (colon vs rectum) and TNM stage (I II vs III IV). Then, we arranged those high quality SNPs into different regions according to their locations on genes to evaluate their functional roles on CRC development.

Results

5114 publications were collected and 1001 of them met our inclusion criteria, which totally included 1788 SNPs in 793 genes or distinct chromosomal loci. Totally, we performed 359 primary and subgroup meta-analyses for 160 SNPs in 96 distinct genes. By utilizing the Venice criteria, we identified 15 high quality SNPs with 25 high credibility significant associations. Furthermore, we artificially divided the high quality SNPs into different groups, based on their SNP loci (exon region, intron region, promoter region, downstream region, non-coding region and intergenic region).

Conclusion

We have identified 15 high quality SNPs which may act as promising genetic biomarkers for clinical NHCRC susceptibility screening and explored their functional roles on the NHCRC development based on their locations on genes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12935-018-0656-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Non-hereditary colorectal cancer, Single nucleotide polymorphisms, Field synopsis, Meta-analysis

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most frequent cancer and the fourth major cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. Genetic factors play an important role in the carcinogenesis of CRC. Traditionally, CRC can be divided into familial CRC (hereditary CRC, HCRC) and sporadic CRC (non-hereditary CRC, NHCRC). HCRC only accounts for 20–25% of all CRC and is mainly attributed to precise high-penetrance mutations [2]. The overwhelming majority of CRC is NHCRC that can be caused by some genetic defects like single nucleotide polymorphism rather than any exact genetic mutation. Understanding of genetic variation is beneficial to strengthen the precaution, screening and early diagnosis of CRC, which is not only for HCRC but also for NHCRC. In a sense, the prediction and control of NHCRC is more expected than HCRC because it occupies the majority of CRC, and the control measures may be feasible and operable.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is a common genetic variation, which may result in different functional products, thus affecting individual susceptibility to diseases. Hence, SNP can be considered as biomarker to predict the risk of sporadic tumor including CRC. During the past three decades, numerous SNPs have been illustrated to be correlated with CRC risk by extensive genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and also candidate-gene association studies (CGAS). Different data based Meta analyses from different angles also reported in the genetic predisposition to NHCRC. Making a general observation of preceding meta-analyses, most of them gathered only a fraction of SNPs and few noticed complete picture of SNPs in NHCRC from a field perspective. It’s worth noting that, there have existed two comprehensive field meta-analyses which demonstrated all CRC risk associated variants, up to 2012, providing directions for future investigators [3, 4]. Inspired by these two articles, we noticed that SNP plays an essential role in the genetic predisposition of CRC, constituting nearly 80% of he significant genetic variants which also include the insertion/deletion polymorphism and variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR). For SNP only, a renewed field synopsis and meta-analysis is required on account of the past 5 years since the latest field synopsis published, and the heterogeneity from ethnicity, primary cancer site and TNM stage must be considered. What’s more, no studies mentioned the role of the whole associated SNPs on CRC development, based on their locations on genes.

In the present systematic review and meta-analysis, we focus on the high quality SNPs (which mean the SNPs are statistically associated with CRC risk in high credibility level, assessed by Venice criteria) in the field of genetic predisposition to NHCRC, involving the correlations of SNPs with ethnicity, primary cancer site (colon or rectal) and TNM stage (I II or III IV). Then, we arranged those high quality SNPs into different regions according to their locations on genes to evaluate their functional roles on CRC development.

Materials and methods

Retrieval strategy

A comprehensive systematic literature search was performed for the publications concerning the association between SNP and risk of NHCRC. We retrieved the database via the PubMed, Web of Science and Embase gateway by using the search terms “(polymorphism or “single nucleotide polymorphism” or SNP or “genome wide association study” or GWAS) and (colon or rectal or rectum or colorectal) and (cancer or tumor or carcinoma or neoplasm)”, up to May 1st, 2017. Moreover, each identified SNP was adopted as a keyword to further improve the search, for instance, ‘XPG’ or ‘rs17655’ in combination with “(colon or rectal or rectum or colorectal) and (cancer or tumor or carcinoma or neoplasm)” as query term.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

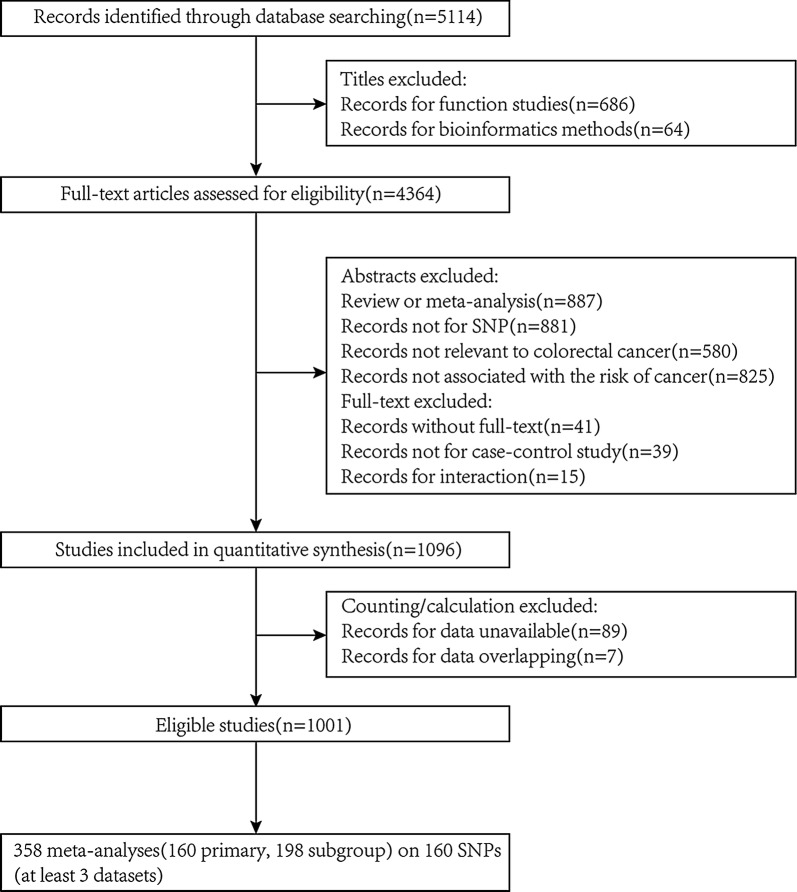

To identify all eligible studies, we adopted the following inclusion criteria: (1) case–control study either candidate-gene association studies (CGAS) or genome-wide association studies (GWAS); (2) explored the correlation between SNP and NHCRC. In addition, the main exclusion criteria were: (1) overlapping studies; (2) no relation to NHCRC or nothing concerning SNPs; (3) no available data or inadaptable SNP genotyping methods; (4) any research published in abstraction form solely (e.g. conference proceedings or scientific meetings) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for selecting eligible studies

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted by two of the authors (Jing Wen and Qian Xu). Items collected from all eligible publications included first author, publication year (unpublished data show study year), race of participants, sample size, genes, SNP locus, genotype counts of cases and controls and HWE in controls. Multiple populations comprising one publication were extracted individually. Concerning GWAS, discovery and replication studies were regarded as separate datasets and were also extracted individually. When it came to eligible articles along with unreported data, we made efforts to contact with the authors.

Assessment of cumulative evidence

The epidemiology credibility of all seemingly significant associations confirmed by our meta-analysis were taken into account by applying Venice criteria [5, 6]. Three categories considered as fundamental criteria to defined the credibility level are as follows:

Amount of evidence was evaluated by the total number of both cases and controls expressing the test alleles or genotypes: category ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’ represent for large-scale, moderate, or little respectively with over 1000, 100–1000 and less than 100 sample size.

Replication was classed based on the statistic of heterogeneity: category ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’ respectively stand for little inconsistency, moderate inconsistency or large inconsistency (no association) with I2 < 25%, 25–50% and > 50%.

Protection from bias was classed as ‘A’ with no bias which was improbably to explain the positive result of association, ‘B’ with no obvious bias but could be the reason for the association, or ‘C’ with demonstrable bias. The general checks for bias include: association lost with removal of initial study; small intensity of association (0.87 < OR < 1.15) and existence of publication bias [7, 8].

According to criteria mentioned above, the accumulative evidence of associations calculated by meta-analysis were regarded as high credibility level (three grades ‘A’), intermediate credibility level (either ‘A’ or ‘B’), and low credibility level (if any grades ‘C’). Notably, the heterogeneity and bias could be exempted if the P value < 1×10−7 after removing the initial study [8].

Statistics

Statistical analyses in our study were conducted by STATA software, version 11.0 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX, USA). All tests were two-tailed and P values ≤ 0.05 were regarded as the statistical significance level only if we emphasized once more. And it would reach a genome-wide significance level if P < 5 × 10−8 [9]. The Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) among genotype distributions of controls was assessed by Chi square test and P values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant disequilibrium. Appraisals of the association between the SNPs and colorectal cancer risk were assessed by pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated by random effect models when heterogeneity of between-study exists [10], otherwise fixed effect model [11]. Begg’s test, as a funnel plot analyses, was implemented to verify significant asymmetry [12] and the modified Egger’s test owns the capacity to correct type I errors through evaluating bias caused by small studies [13]. P value less than 0.10 was regarded as the threshold in both Begg’s or Egger’s test.

In addition, q value was considered as a measure for statistically significant findings in terms of false discovery rate (FDR), which is the proportion that significant findings are truly null hypotheses. For instance, 5% false discovery rate means that among all statistically significant SNPs, 5% of them are not actually associated with CRC risk. And we also considered 0.05 as the threshold of q value [14, 15].

Results

Features of eligible studies

According to the screening process showed in Fig. 1, 5114 publications were collected and 1001 of them met our inclusion criteria, which totally included 1788 SNPs in 793 genes or distinct chromosomal loci with 2,200,290 subjects extracted (cases: 971,074, ratio: 44%, range: 8–10,409, mean: 550).

Based on the ethnicity of study population, investigations for Caucasian (57%) were slightly more than those for Asian. Besides, over a quarter of the available articles detailed the primary site (colon vs rectum) of colorectal cancer, and the articles that mentioned TNM stage of UICC/AJCC also account for 13%. Additionally, nearly a half of the investigated SNPs were exonic SNPs (45%), others were located in intron (20%), 3′-UTR (4%), 5′-UTR (1%), upstream (14%), downstream regions (2%) non-coding (7%) or intergenic regions (6%).

Meta analysis findings

Totally, we performed 359 meta-analyses for 160 SNPs in 96 distinct genes. Each meta-analysis involved at least three studies (CGAS or GWAS) with available co-dominant genotypes and HWE. Of these, 160 were primary meta-analyses and 199 were subgroups meta-analyses defined by ethnicity (Caucasian, n = 90; Asian, n = 53), primary cancer site (colon, n = 22; rectum, n = 14) and TNM stage (I II, n = 10; III IV, n = 10). Of the 359 meta-analyses conducted, 90 (25%) attained statistically significant findings, other 269 being non-significant. Furthermore, 40.3% (n = 145) had little or no heterogeneity (I2 < 25%), 14.2% (n = 51) had moderate heterogeneity (25% ≤ I2 ≤ 50%), and 45.5% (n = 164) had large heterogeneity (I2 > 50%). Comparing the proportion of large study heterogeneity, we found that it was significantly lower for 90 positive SNPs than the remaining SNPs (19.8% and 46.5%, respectively; P value = 6.88E−6). Evaluation of publication bias conducted for all meta-analyses showed that totally 52 of them had statistically significant publication bias, 15 for ethnicity subgroup, 4 for cancer sites subgroup and 2 for TNM stage subgroup. In sensitivity analyses, eight SNPs was no longer significant after removing one record from meta-analysis and five of them showed more than 5% alteration of OR value (rs3918242, rs1048943, rs5498, rs4444903, rs10808556).

Comprehensively considering the impact of the evidence amount, replication consistency (heterogeneity), and protection from bias (derived from publication bias, initial study influence and OR value) on the cumulative evidence, we applied the Venice criteria that could assess the epidemiological credibility for all significant findings. Thus, the high, intermediate and low credibility level of cumulative evidence were detected, which respectively account for 28% (n = 25), 16% (n = 14), 56% (n = 51). Publication bias was the most common cause (41/65) for non-high-quality evidence, and the inter-study heterogeneity could be the second (33/65). From the 25 high credibility significant associations, we identified 15 distinct high quality SNPs which were presented in Fig. 5.

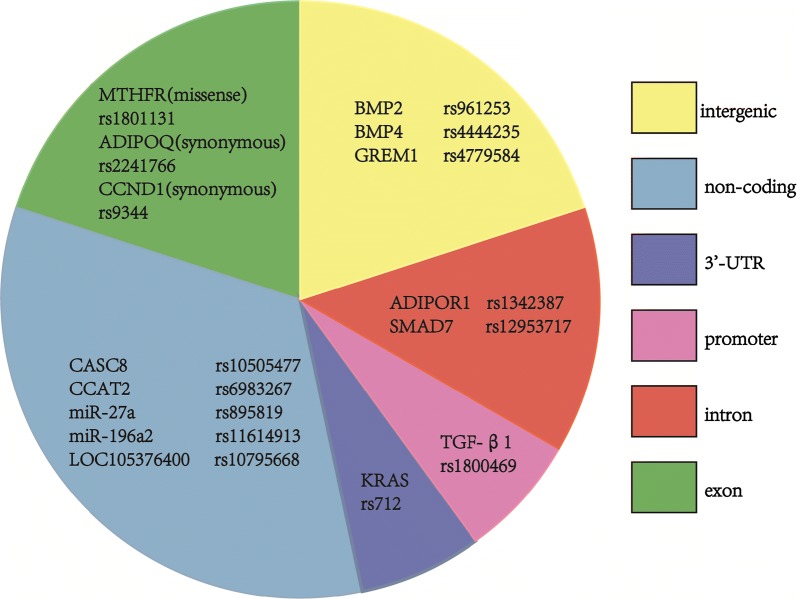

Fig. 5.

We artificially divided the 15 distinct high quality SNPs into six groups, based on their SNP loci on genes

Results from whole population analysis

Significant associations in primary meta-analysis are reported in Table 1, characterized by high (n = 10), intermediate (n = 3) or low quality (n = 23). Seven of the ten high quality SNPs reached a genome-wide significance level, P < 5 × 10−8 (BMP2 rs961253, CASC8 rs1505477, BMP4 rs4444235, SMAD7 rs12953717, CCAT2 rs6983267, TGF-β1 rs1800469, LOC105376400 rs10795668 and GREM1-SCG5 rs4779584). Other three high quality SNPs were: GREM1-SCG5 rs4779584, ADIPOQ rs2241766 and miR-27a rs895819.

Table 1.

Genetic variants associated with NHCRC after meta-analyses of at least three independent datasets (primary meta-analyses)

| Gene | SNPs | Chr | Allelesa | Datasets | Cases | Controls | OR | CI-U | CI-L | P | FDR | Venice criteria | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP2 | rs961253 | 20 | C-A | 23 | 40507 | 40740 | 1.121 | 1.098 | 1.144 | 7.77E−27 | 7.15E−25 | AAA | High |

| CASC8 | rs10505477 | 8 | T-C | 13 | 12933 | 13259 | 0.856 | 0.828 | 0.886 | 9.27E−19 | 2.84E−17 | AAA | High |

| BMP4 | rs4444235 | 14 | T-C | 27 | 39030 | 39934 | 1.083 | 1.061 | 1.105 | 8.24E−15 | 1.89E−13 | AAA | High |

| SMAD7 | rs12953717 | 18 | C-T | 9 | 10782 | 10011 | 1.163 | 1.118 | 1.209 | 4.93E−14 | 8.00E−13 | AAA | High |

| CCAT2 | rs6983267 | 8 | G-T | 26 | 33098 | 30415 | 0.845 | 0.807 | 0.884 | 3.35E−13 | 3.86E−12 | AAA | High |

| TGF-β1 | rs1800469 | 19 | C-T | 21 | 17404 | 36234 | 0.911 | 0.887 | 0.936 | 1.59E−11 | 1.62E−10 | AAA | High |

| LOC105376400 | rs10795668 | 10 | G-A | 8 | 5744 | 5481 | 0.837 | 0.791 | 0.886 | 8.43E−10 | 5.27E−09 | AAA | High |

| GREM1-SCG5 | rs4779584 | 15 | C-T | 16 | 25151 | 24548 | 1.154 | 1.093 | 1.217 | 1.69E−07 | 8.62E−07 | AAA | High |

| ADIPOQ | rs2241766 | 3 | T-G | 7 | 2400 | 2972 | 1.216 | 1.115 | 1.326 | 9.33E−06 | 3.07E−05 | AAA | High |

| miR-27a | rs895819 | 19 | T-C | 5 | 1562 | 1852 | 1.192 | 1.076 | 1.320 | 0.001 | 0.002 | AAA | High |

| ADIPOR1 | rs1342387 | 1 | G-A | 5 | 1843 | 2563 | 0.824 | 0.755 | 0.900 | 1.82E−05 | 5.76E−05 | ABA | Intermediate |

| ICAM1 | rs5498 469 | 19 | A-G | 3 | 358 | 335 | 0.740 | 0.595 | 0.920 | 0.007 | 0.012 | BAA | Intermediate |

| PARP-1 | rs1136410 | 1 | T-C | 3 | 808 | 1849 | 1.181 | 1.043 | 1.337 | 0.009 | 0.015 | ABA | Intermediate |

| RHPN2 | rs10411210 | 19 | C-T | 15 | 22299 | 23280 | 0.881 | 0.844 | 0.919 | 6.12E−09 | 4.69E−08 | ABC | Low |

| SMAD7 | rs4464148 | 18 | T-C | 8 | 9736 | 8573 | 1.142 | 1.091 | 1.196 | 1.62E−08 | 1.15E−07 | AAC | Low |

| SMAD7 | rs4939827 | 18 | T-C | 17 | 16336 | 15443 | 0.859 | 0.813 | 0.908 | 5.94E−08 | 3.42E−07 | ACA | Low |

| CDH1 | rs9929218 | 16 | G-A | 17 | 22459 | 24079 | 0.930 | 0.903 | 0.958 | 1.51E−06 | 5.80E−06 | AAC | Low |

| COLCA1 | rs3802842 | 11 | A-C | 18 | 18043 | 17876 | 1.149 | 1.086 | 1.216 | 1.62E−06 | 5.97E−06 | ACC | Low |

| NA | rs719725 | 9 | A-C | 14 | 11820 | 13119 | 0.934 | 0.900 | 0.968 | 2.17E−04 | 5.56E−04 | AAC | Low |

| MLH1 | rs63750447 | 3 | T-A | 6 | 1427 | 1491 | 2.449 | 1.426 | 4.205 | 0.001 | 0.002 | CCC | Low |

| XPG | rs17655 | 13 | G-C | 8 | 4752 | 5648 | 1.101 | 1.036 | 1.170 | 0.002 | 0.004 | AAC | Low |

| NAT2 | rs1801280 | 8 | T-C | 3 | 2066 | 2581 | 0.876 | 0.807 | 0.952 | 0.002 | 0.004 | AAC | Low |

| NA | rs11568820 | 12 | G-A | 5 | 4278 | 4693 | 1.112 | 1.036 | 1.194 | 0.003 | 0.006 | AAC | Low |

| VDR | rs1544410 | 12 | G-A | 14 | 10404 | 11213 | 0.768 | 0.633 | 0.930 | 0.007 | 0.012 | ACC | Low |

| CCND1 | rs9344 | 11 | G-A | 21 | 4757 | 6680 | 1.119 | 1.026 | 1.220 | 0.011 | 0.017 | ACC | Low |

| CDH1 | rs16260 | 16 | C-A | 8 | 6062 | 7045 | 0.934 | 0.884 | 0.988 | 0.016 | 0.023 | AAC | Low |

| EGF | rs4444903 | 4 | G-A | 8 | 1234 | 1377 | 0.819 | 0.692 | 0.969 | 0.020 | 0.027 | ACC | Low |

| GREM1 | rs16969681 | 15 | C-T | 6 | 7300 | 9039 | 1.157 | 1.022 | 1.311 | 0.021 | 0.028 | ACA | Low |

| MTRR | rs1801394 | 5 | A-G | 19 | 8409 | 11893 | 1.046 | 1.004 | 1.089 | 0.030 | 0.036 | ABC | Low |

| NQO1 | rs1800566 | 16 | C-T | 13 | 6016 | 6905 | 1.142 | 1.013 | 1.288 | 0.030 | 0.036 | ACC | Low |

| MMP9 | rs3918242 | 20 | C-T | 5 | 829 | 1096 | 0.803 | 0.657 | 0.980 | 0.031 | 0.037 | BAC | Low |

| ERCC1 | rs11615 | 19 | C-T | 5 | 982 | 1251 | 1.147 | 1.011 | 1.302 | 0.033 | 0.037 | AAC | Low |

| APC | rs459552 | 5 | A-T | 13 | 9440 | 10200 | 0.950 | 0.905 | 0.997 | 0.037 | 0.041 | AAC | Low |

| CYP1A1 | rs1048943 | 15 | A-G | 13 | 3509 | 3960 | 1.287 | 1.011 | 1.637 | 0.040 | 0.043 | ACA | Low |

| GH1 | rs2665802 | 17 | T-A | 3 | 2740 | 3198 | 0.929 | 0.863 | 0.999 | 0.046 | 0.047 | AAC | Low |

| RETN | rs1862513 | 19 | C-G | 3 | 1013 | 1049 | 1.145 | 1.000 | 1.311 | 0.050 | 0.050 | ABC | Low |

Chr chromosome, FDR false discovery rate

aMajor alleles-minor alleles; Venice criteria: A (high), B (moderate), C (weak) credibility for three parameters (amount of evidence, heterogeneity and bias; see text and Additional file 1 for more details); level of evidence: overall level of summary evidence according to the Venice criteria

Results from subgroup analyses

Significant associations in subgroup analyses were shown in Table 2, featured with high (n = 15), intermediate (n = 11) or low quality (n = 28). Results from three stratification analyses (ethnicity, primary cancer site and TNM stage) were illustrated as follows.

Table 2.

Genetic variants associated with NHCRC after meta-analyses of at least three independent datasets (subgroup meta-analyses)

| Gene | SNPs | Chr | Allelesa | Datasets | Subgroups | Cases | Controls | OR | CI-U | CI-L | P | FDR | Venice criteria | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β1 | rs1800469 | 19 | C-T | 16 | Asian | 14494 | 32550 | 0.911 | 0.885 | 0.938 | 2.43E−10 | 2.03E−09 | AAA | High |

| LOC105376400 | rs10795668 | 10 | G-A | 4 | Asian | 2479 | 2659 | 0.803 | 0.741 | 0.872 | 1.37E−07 | 7.41E−07 | AAA | High |

| KRAS | rs712 | 12 | G-T | 3 | Asian | 1355 | 1219 | 1.405 | 1.226 | 1.610 | 9.99E−07 | 4.37E−06 | AAA | High |

| ADIPOR1 | rs1342387 | 1 | G-A | 3 | Asian | 1218 | 1724 | 0.779 | 0.697 | 0.870 | 9.22E−06 | 3.07E−05 | AAA | High |

| ADIPOQ | rs2241766 | 3 | T-G | 5 | Asian | 2143 | 2666 | 1.215 | 1.111 | 1.328 | 6.03E−05 | 1.63E−04 | AAA | High |

| miR-196a2 | rs11614913 | 12 | C-T | 4 | Asian | 1397 | 2040 | 0.836 | 0.757 | 0.922 | 3.54E−04 | 8.79E−04 | AAA | High |

| BMP2 | rs961253 | 20 | C-A | 21 | Caucasian | 38172 | 38356 | 1.115 | 1.092 | 1.139 | 3.57E−24 | 1.64E−22 | AAA | High |

| BMP4 | rs4444235 | 14 | T-C | 22 | Caucasian | 34181 | 34254 | 1.086 | 1.063 | 1.110 | 5.22E−14 | 8.00E−13 | AAA | High |

| SMAD7 | rs12953717 | 18 | C-T | 8 | Caucasian | 10640 | 9845 | 1.161 | 1.116 | 1.208 | 1.16E−13 | 1.53E−12 | AAA | High |

| GREM1-SCG5 | rs4779584 | 15 | C-T | 12 | Caucasian | 21029 | 19867 | 1.16 | 1.092 | 1.232 | 1.45E−06 | 5.80E−06 | AAA | High |

| LOC105376400 | rs10795668 | 10 | G-A | 4 | Caucasian | 3265 | 2822 | 0.87 | 0.804 | 0.942 | 0.001 | 0.002 | AAA | High |

| CCND1 | rs9344 | 11 | G-A | 7 | Rectum | 775 | 2241 | 1.272 | 1.126 | 1.436 | 1.05E−04 | 2.77E−04 | AAA | High |

| MTHFR | rs1801131 | 1 | A-C | 6 | Rectum | 1625 | 2987 | 0.858 | 0.775 | 0.949 | 0.003 | 0.006 | AAA | High |

| LOC105376400 | rs10795668 | 10 | G-A | 3 | TNM12 | 766 | 2423 | 0.773 | 0.682 | 0.875 | 4.65E−05 | 1.38E−04 | AAA | High |

| CCND1 | rs9344 | 11 | G-A | 4 | TNM12 | 343 | 740 | 1.366 | 1.134 | 1.646 | 0.001 | 0.002 | AAA | High |

| ABCB1 | rs1045642 | 7 | C-T | 5 | Asian | 1567 | 1857 | 0.866 | 0.786 | 0.955 | 0.004 | 0.007 | ABA | Intermediate |

| CYP1A1 | rs1048943 | 15 | A-G | 7 | Caucasian | 1779 | 1946 | 1.251 | 1.038 | 1.508 | 0.019 | 0.026 | BAA | Intermediate |

| MDM2 | rs2279744 | 12 | T-G | 4 | Caucasian | 1325 | 473 | 0.826 | 0.704 | 0.969 | 0.019 | 0.026 | ABA | Intermediate |

| CCAT2 | rs10090154 | 8 | C-T | 3 | Caucasian | 1084 | 1049 | 1.254 | 1.028 | 1.529 | 0.026 | 0.033 | BAA | Intermediate |

| VDR | rs731236 | 12 | T-C | 3 | Colon | 677 | 578 | 1.291 | 1.06 | 1.573 | 0.011 | 0.017 | BAA | Intermediate |

| PPARG | rs1801282 | 3 | C-G | 4 | Colon | 998 | 3368 | 0.772 | 0.619 | 0.963 | 0.022 | 0.029 | BAA | Intermediate |

| TP53 | rs1042522 | 17 | G-C | 5 | TNM12 | 249 | 975 | 1.41 | 1.147 | 1.734 | 0.001 | 0.002 | BAA | Intermediate |

| XRCC1 | rs25487 | 19 | G-A | 3 | TNM12 | 165 | 420 | 1.323 | 1.021 | 1.713 | 0.034 | 0.038 | BBA | Intermediate |

| miR-196a2 | rs11614913 | 12 | C-T | 3 | TNM12 | 279 | 1249 | 0.823 | 0.682 | 0.994 | 0.043 | 0.045 | ABA | Intermediate |

| MTHFR | rs1801133 | 1 | C-T | 4 | TNM34 | 207 | 715 | 1.715 | 1.338 | 2.200 | 2.09E−05 | 6.39E−05 | BAA | Intermediate |

| CCND1 | rs9344 | 11 | G-A | 5 | TNM34 | 340 | 860 | 1.254 | 1.046 | 1.503 | 0.014 | 0.021 | ABA | Intermediate |

| CCAT2 | rs6983267 | 8 | G-T | 8 | Asian | 11190 | 10699 | 0.846 | 0.791 | 0.906 | 1.43E−06 | 5.80E−06 | ACA | Low |

| miR-27a | rs895819 | 19 | T-C | 3 | Asian | 1174 | 1212 | 1.237 | 1.096 | 1.395 | 0.001 | 0.002 | AAC | Low |

| BMP4 | rs4444235 | 14 | T-C | 4 | Asian | 4136 | 4765 | 1.089 | 1.026 | 1.156 | 0.005 | 0.009 | ABC | Low |

| MMP9 | rs3918242 | 20 | C-T | 4 | Asian | 702 | 888 | 0.754 | 0.605 | 0.939 | 0.012 | 0.018 | BAC | Low |

| PTGS2 | rs20417 | 1 | G-C | 3 | Asian | 1285 | 1740 | 1.422 | 1.08 | 1.872 | 0.012 | 0.018 | BBC | Low |

| GREM1-SCG5 | rs4779584 | 15 | C-T | 4 | Asian | 4122 | 4681 | 1.134 | 1.003 | 1.283 | 0.045 | 0.047 | ACC | Low |

| C11orf92–C11orf93 | rs3802842 | 11 | A-C | 11 | Caucasian | 12983 | 12139 | 1.139 | 1.095 | 1.184 | 6.32E−11 | 5.81E−10 | ABC | Low |

| SMAD7 | rs4464148 | 18 | T-C | 7 | Caucasian | 9020 | 7860 | 1.139 | 1.087 | 1.194 | 4.74E−08 | 3.11E−07 | AAC | Low |

| CCAT2 | rs6983267 | 8 | G-T | 17 | Caucasian | 21026 | 18580 | 0.85 | 0.798 | 0.904 | 2.97E−07 | 1.44E−06 | ACA | Low |

| SMAD7 | rs4939827 | 18 | T-C | 13 | Caucasian | 12657 | 11621 | 0.853 | 0.801 | 0.908 | 5.86E−07 | 2.69E−06 | ACA | Low |

| CDH1 | rs9929218 | 16 | G-A | 13 | Caucasian | 18291 | 19311 | 0.926 | 0.897 | 0.956 | 2.17E−06 | 7.67E−06 | AAC | Low |

| RHPN2 | rs10411210 | 19 | C-T | 12 | Caucasian | 19240 | 20177 | 0.859 | 0.799 | 0.925 | 5.25E−05 | 1.51E−04 | ACA | Low |

| TERT | rs2736100 | 5 | G-T | 8 | Caucasian | 14486 | 15588 | 1.072 | 1.036 | 1.109 | 5.83E−05 | 1.62E−04 | AAC | Low |

| NA | rs719725 | 9 | A-C | 12 | Caucasian | 10035 | 10281 | 0.935 | 0.898 | 0.973 | 0.001 | 0.002 | AAC | Low |

| NQO1 | rs1800566 | 16 | C-T | 9 | Caucasian | 4496 | 4794 | 1.119 | 1.039 | 1.206 | 0.003 | 0.006 | AAC | Low |

| CDH1 | rs16260 | 16 | C-A | 5 | Caucasian | 5603 | 6646 | 0.927 | 0.876 | 0.981 | 0.008 | 0.013 | AAC | Low |

| TGF-β1 | rs1800469 | 19 | C-T | 5 | Caucasian | 2910 | 3684 | 0.915 | 0.845 | 0.987 | 0.021 | 0.028 | ABC | Low |

| MTR | rs1805087 | 1 | A-G | 10 | Caucasian | 6884 | 8873 | 0.936 | 0.884 | 0.991 | 0.023 | 0.029 | ABC | Low |

| NA | rs11568820 | 12 | G-A | 4 | Caucasian | 2701 | 2721 | 1.107 | 1.011 | 1.213 | 0.028 | 0.035 | AAC | Low |

| RFC/SLC19A1 | rs1051266 | 21 | A-G | 5 | Caucasian | 1922 | 3142 | 0.915 | 0.843 | 0.992 | 0.032 | 0.037 | AAC | Low |

| GREM1 | rs16969681 | 15 | C-T | 5 | Caucasian | 6411 | 8146 | 1.175 | 1.003 | 1.378 | 0.046 | 0.047 | ACA | Low |

| CCAT2 | rs6983267 | 8 | G-T | 5 | Colon | 1593 | 2439 | 0.823 | 0.706 | 0.959 | 0.012 | 0.018 | ACA | Low |

| CCND1 | rs9344 | 11 | G-A | 8 | Colon | 877 | 2394 | 1.147 | 1.024 | 1.284 | 0.018 | 0.025 | AAC | Low |

| MSH6 | rs1042821 | 2 | C-T | 3 | Colon | 3448 | 5447 | 1.091 | 1.008 | 1.181 | 0.032 | 0.037 | AAC | Low |

| SMAD7 | rs4939827 | 18 | T-C | 4 | colon | 2259 | 2809 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.995 | 0.037 | 0.041 | ABC | Low |

| ABCB1 | rs1045642 | 7 | C-T | 5 | Colon | 469 | 635 | 1.198 | 1.009 | 1.423 | 0.039 | 0.042 | AAC | Low |

| CCAT2 | rs6983267 | 8 | G-T | 4 | Rectum | 652 | 1718 | 0.756 | 0.599 | 0.953 | 0.018 | 0.025 | ACA | Low |

| CCAT2 | rs6983267 | 8 | G-T | 4 | TNM34 | 747 | 2185 | 0.834 | 0.739 | 0.941 | 0.003 | 0.006 | AAC | Low |

Chr chromosome, FDR false discovery rate

aMajor alleles-minor alleles; Venice criteria: A (high), B (moderate), C (weak) credibility for three parameters (amount of evidence, heterogeneity and bias; see text and Additional file 1 for more details); level of evidence: overall level of summary evidence according to the Venice criteria

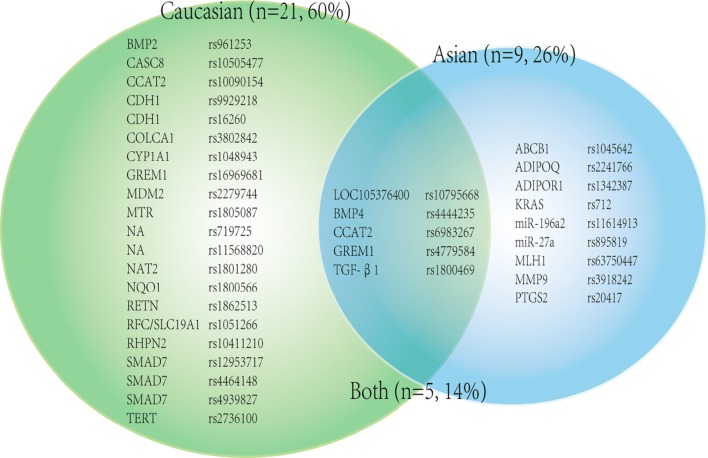

Results based-on ethnicity

Disparate race were mentioned in 35 significant associations (see Fig. 2). 21 (60%) of them were identified in Caucasian only (18 from Caucasian subgroup meta-analyses and 3 from primary meta-analyses which included only Caucasian ancestry), 9 (25.7%) of them were indicated in Asian only (8 from Asian subgroup meta-analyses and 1 from primary meta-analyses which only covered Asian ancestry), and 5 (14.3%) SNPs (all from subgroup meta-analyses) obtained their correlations in both Caucasian and Asian.

Fig. 2.

Venn diagram demonstrating the distribution of SNPs associated with colorectal cancer in subjects with Asian or Caucasian ethnicity or associated with both ancestries

Totally 11 high quality SNPs were found in ethnicity subgroup analyses, 6 from Asian subgroup (TGF-β1 rs1800469, LOC105376400 rs10795668, KRAS rs712, ADIPOR1 rs1342387, ADIPOQ rs2241766 and miR-196a2 rs11614913) and 5 from Caucasian subgroup (BMP2 rs961253, BMP4 rs4444235, SMAD7 rs12953717, GREM1-SCG5 rs4779584 and LOC105376400 rs10795668).

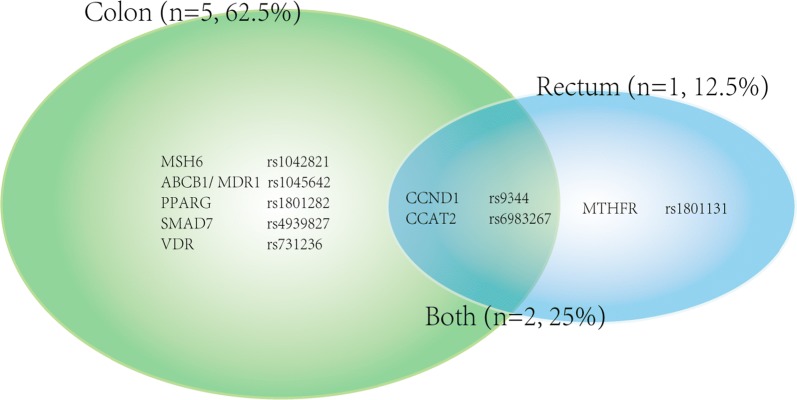

Results based-on primary cancer site

Different cancer sites were mentioned in 8 significant SNPs (see Fig. 3). 5 (62.5%) of them showed their unique associations with colon cancer in subgroup analyses, 1 (12.5%) showed a sole association with rectum cancer in subgroup analysis, and 2 (25%) revealed their correlations with either colon or rectum cancer. Two high quality SNPs were found in rectum subgroup (CCND1 rs9344 and MTHFR rs1801131).

Fig. 3.

Venn diagram demonstrating the distribution of SNPs associated with colon or rectal cancer or associated with both primary cancer sites

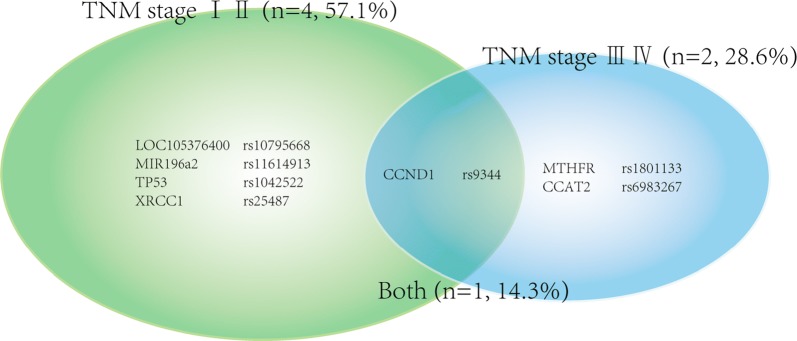

Results based-on cancer TNM stage

Subgroup meta-analyses of TNM stage demonstrated 7 SNPs with significant correlations (see Fig. 4). 4 (57.1%) of them simply correlated with TNM stage (I II), 2 (28.6%) of them related to TNM stage (III IV), and only 1 (14.3%) SNP showed it’s correlation with any TNM stage of CRC. Among the 7 significant SNPs, only 2 high quality SNPs (LOC105376400 rs10795668 and CCND1 rs9344) were identified.

Fig. 4.

Venn diagram demonstrating the distribution of SNPs associated with specific coloretal cancer TNM stage (I II vs III IV) or associated with full stage

Results based-on SNP location

From 25 high credibility significant associations, 15 distinct high quality SNPs were identified. In order to further explore the role of these high quality SNPs, we artificially divided them into different groups, based on their SNP loci (exon region, intron region, promoter region, downstream region, non-coding region and intergenic region), which was displayed in Fig. 5. What’s more, we also revealed the chromosome distribution of each high quality SNPs.

Of the 15 high quality SNPs, 3 are located in exon region (2 synonymous variants: ADIPOQ rs2241766 and CCND1 rs9344; one missense variant: MTHFR rs1801131), 2 in intron region (SMAD7 rs12953717 and ADIPOR1 rs1342387), one in promoter region (TGF-β rs1800469 SNP), one in 3′-UTR region (KRAS rs712) and 5 in non-coding region (CASC8 rs10505477, CCAT2 rs6983267, LOC105376400 rs10795668, miR-27a rs895819, miR-196a2 rs11614913). Distinct from those functional SNPs, there are still 3 high quality SNPs located in intergenic region (BMP2 rs961253, BMP4 rs4444235 and GREM1-SCG5 rs4779584).

The chromosomes distribution of each high quality SNPs were also displayed. In general, the SNPs are evenly and extensively distributed in half of the chromosomes including chromosome 1, 3, 8, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 18, 19, 20.

Discussion

In this article, we systematically reviewed the associations between 160 SNPs in 96 distinct genes or chromosomal loci and predisposition to NHCRC or to subgroups identified by ethnicity (Asian vs Caucasian), primary cancer site (colon vs rectum), TNM stage (I II vs III IV) and SNP locations on genes, with the quality assessment of cumulative evidence, and 15 high quality SNPs were ultimately confirmed. Above all, innovations and strengths of the present study ought to be addressed. First, a most comprehensive evaluation of the literature in the field of genetic predisposition to NHCRC was conducted. Second, we first reported 20 SNPs in primary meta-analysis, 24 SNPs in “primary cancer site” subgroup analysis (15 for colon, 9 for rectum) and 10 SNPs in “TNM stage” subgroup analysis. Third, for exploring the functional roles of high quality SNPs on the NHCRC development, we first divided them into six different groups, based on SNP loci on genes. This study provides the latest evidence and clues for the genetic susceptibility to NHCRC. In spite of these strengths, limitations cannot be ignored. First, we only considered allelic genetic model because it was widely regarded as a conservative model between the dominant and recessive model [16]. Second, type I error might exist by utilizing same series in more than one meta-analysis. However, after calculating q values, the incidence of type I error could be minimized. Third, we didn’t analyze gene–gene or gene–environment interactions due to the insufficiency data. Future specialized studies should be designed to reveal their interactions.

High quality SNPs with NHCRC risk

Facing the excessive SNPs with significant associations, it’s crucial to conduct a quality evaluation scientifically to those significant correlations. By utilizing the Venice criteria, we identified 15 high quality SNPs with 25 high credibility significant associations, which may act as promising genetic biomarkers for clinical NHCRC susceptibility screening.

For the whole population, 10 high quality SNPs were evaluated and shown in Table 1. Comparing our results with two published field meta-analyses [3, 4], we found that 8 of the 10 SNPs were assessed as high quality SNPs for the first time, which meant they were used to be non-high-quality SNPs (with intermediate or low credibility level evidence), or even unreported in the past. Interestingly, by observing the gene functions of these high quality SNPs, we noticed that half of them participated in TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway, including TGF-β, SMAD7, BMP2, BMP4 and GREM1. This discovery could indirectly verified the crucial role of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway on CRC pathogenesis by regulating their target genes [17]. In addition, there were four other high quality SNPs in non-coding RNA (including 1 micro-RNA: miR-27a; 3 long non-coding RNA: CASC8, CCAT2 and LOC105376400), which revealed that the aberrant expression of non-coding RNA could also be tightly related to CRC diagnosis [18–20]. Moreover, there was also one high quality SNP in ADIPOQ (adiponectin) gene, reminding that the deficiency of adiponectin might be one of the fundamental risk factors for NHCRC [21, 22].

From the perspective of ethnicity, the apparent contrast between Caucasian and Asian population on the distribution of associated SNPs was presented in Fig. 2, which suggested that the molecular mechanism of CRC development couldn’t always be the same among different ethnicities. Of note, 6 high quality SNPs were evaluated in Asian subgroup, all of which were first identified as high quality SNPs for Asian population; while 5 high quality SNPs were evaluated in Caucasian subgroup, and 3 were newly identified for Caucasian population. Observing the gene functions of these SNPs, KRAS, an important oncogene, caught our attention. It participated in RAF/MEK/MAPK, ERK and AKT signal pathways, regulating the CRC cell proliferation and differentiation [23, 24].

From the aspect of primary cancer location, the different findings between colon and rectal cancer indicated that they not only differ in anatomic site, but also in molecular profile. A study illustrated that colon and rectal cancer differ in embryological origin, metastasis manner and mutational profile, requiring various neo-adjuvant treatment and surgical methods [25]. Nevertheless, none of the two publications have been concerned with the “primary cancer location” subgroup analyses. Herein, 2 high quality SNPs were demonstrated in rectal subgroup analysis. These results elucidated that the risk factors for rectum cancer development might be the aberrant expression of MTHFR (which leaded to abnormal folate metabolism [26–28]) or CCND1 (which could promote cell cycle G1/S transition [29, 30]).

From malignant level perspective, TNM stage subgroup was first analyzed in our study with a high positive rate (8/20, 40%) and the diversity between stage I II and III IV also exist. It illustrated that SNPs could not only predict the NHCRC development, but also remind the degree of malignancy, directing the physical test frequency for patient and the treatment for doctor. Based on the limited pathological parameters provided by researchers, only 20 SNPs were analyzed in this subgroup and 2 of them (LOC105376400 rs10795668 and CCND1 rs9344) were identified as high quality SNPs in TNM stage (I II). Further studies should pay more attention to the association between polymorphisms and NHCRC malignancy degree.

Functional roles of high quality SNPs based on location

SNPs can influence the CRC susceptibility through complicated genetic and epigenetic mechanisms which depends on the their gene functions and their locations on genes. Hence, we arranged 15 high quality SNPs into different regions (including exon, intron, promoter, non-coding and also intergenic region) to focus on their feasible mechanisms on facilitating NHCRC development.

In exon region, the missense SNP (MTHFR rs1801131) make its contribution to the NHCRC by reducing the activity of enzyme [31, 32]. Besides, the prime mechanisms for synonymous SNPs are their influence on mRNA expression level by altering splicing or stability of mRNA (such as ADIPOQ rs2241766 and CCND1 rs9344) [33–36].

Indeed, SNPs in intron region probably exert larger effects on target genes than we hitherto thought, on account of the plenty of functional elements in this region, including cis-acting RNA elements, intron splice enhancers and intron splice silencers and so on [37]. However, high quality SNPs in this region are shown to be associated with mRNA expression level without precise interpretation (such as SMAD7 rs12953717 and rs4464148) [38]. Hence, the mechanisms of high quality intronic SNPs should not be ignored by further researchers and studies concerned with these SNPs are still found wanting.

Regarding the SNPs located in promoter region, it has revealed that they can alter the binding ability to transcription factors, affecting the transcriptional efficiency of genes (such as TGF-β1 rs1800469) [39]. Moreover, the 3′-UTR region of genes contain multiple microRNA binding sites. Hence, SNPs in this region are speculated to disrupt the microRNA binding sites, leading to an increased expression level of target genes (such as KRAS rs712, predicted by a bioinformatics website: ‘snpinfo.niehs.nih.gov’).

For SNPs in non-coding region, we found that high quality SNPs were detected in both microRNAs (miRNA) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNA), which could indirectly participate in CRC cancerogenesis by interacting with encoding mRNA. SNPs in miRNA have a crucial influence on its synthesis and down-regulation (such as miR-196a2 rs11614913 and miR-27a rs895819) [20, 40, 41] and can also regulate the binding capacity to target genes (such as miR-196a2 rs11614913) [42]. In addition, SNPs in lncRNA can lead to an aberrant expression of lncRNA by disrupting its vital regulatory region (such as CASC8 rs1505477) [43], and regulate the expression level of target genes by modulating the binding of transcription factors (TFs) to its promoter region (such as CASC8 rs1505477, CCAT2 rs6983267 and LOC105376400 rs10795668) [44–47].

Furthermore, their were also three high quality SNPs: BMP2 rs961253, BMP4 rs4444235 and GREM1 rs4779584, not located in known genes. Further studies are required to explain their association with CRC risk. Additionally, data in our study revealed that high quality SNPs are diffused distributed in coding or non-coding region of chromosomes: 1, 3, 8, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 18, 19 and 20, which indicated the complicated molecular mechanisms for CRC generation involve numerous genomic and epigenomic variants.

Conclusion and expectations

In this systematic review and large-scale meta-analysis, we identified 15 distinct high quality SNPs associated with NHCRC risk and first reported 20 SNPs in primary meta-analysis, 24 SNPs in subgroup analysis (15 for colon, 9 for rectum) and 10 SNPs in TNM stage subgroup analysis. The comprehensive survey in the field of genetic predisposition to sporadic colorectal cancer generalized the current situation of the study on NHCRC susceptibility SNPs, providing useful data for investigators to design future studies.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1. Detailed information of meta-analyses results for 25 high credibility significant associations. Table S2. Meta-analysis results: SNPs with non-significant associations to CRC risk.

Authors’ contributions

YY and QX conceived and designed the study. JW and QX were responsible for the data extraction, cumulative evidence assessment and statistics. JW and YY wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported partly by the grants from the 13th 5 years for the National Key Research and Development Program & Key Special Project (2018YFC1311600).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- HCRC

hereditary CRC

- NHCRC

non-hereditary CRC

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- CGAS

candidate-gene association studies

- VNTR

variable number of tandem repeat

- ORs

odds ratios

- CIs

confidence intervals

- HWE

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- CIs

confidence intervals

- FDR

false discovery rate

Contributor Information

Qian Xu, Email: qxu@cmu.edu.cn.

Yuan Yuan, Email: yuanyuan@cmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de la Chapelle A. Genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(10):769–780. doi: 10.1038/nrc1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theodoratou E, Montazeri Z, Hawken S, Allum GC, Gong J, Tait V, Kirac I, Tazari M, Farrington SM, Demarsh A, et al. Systematic meta-analyses and field synopsis of genetic association studies in colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(19):1433–1457. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma X, Zhang B, Zheng W. Genetic variants associated with colorectal cancer risk: comprehensive research synopsis, meta-analysis, and epidemiological evidence. Gut. 2014;63(2):326–336. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ioannidis JP, Boffetta P, Little J, O’Brien TR, Uitterlinden AG, Vineis P, Balding DJ, Chokkalingam A, Dolan SM, Flanders WD, et al. Assessment of cumulative evidence on genetic associations: interim guidelines. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(1):120–132. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khoury MJ, Bertram L, Boffetta P, Butterworth AS, Chanock SJ, Dolan SM, Fortier I, Garcia-Closas M, Gwinn M, Higgins JP, et al. Genome-wide association studies, field synopses, and the development of the knowledge base on genetic variation and human diseases. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(3):269–279. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langevin SM, Ioannidis JP, Vineis P, Taioli E, Genetic susceptibility to environmental carcinogens g Assessment of cumulative evidence for the association between glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms and lung cancer: application of the Venice interim guidelines. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20(10):586–597. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32833c3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatzinasiou F, Lill CM, Kypreou K, Stefanaki I, Nicolaou V, Spyrou G, Evangelou E, Roehr JT, Kodela E, Katsambas A, et al. Comprehensive field synopsis and systematic meta-analyses of genetic association studies in cutaneous melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(16):1227–1235. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng C, Matsuda K, Jia WH, Chang J, Kweon SS, Xiang YB, Shin A, Jee SH, Kim DH, Zhang B, et al. Identification of susceptibility loci and genes for colorectal cancer risk. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(7):1633–1645. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med. 2006;25(20):3443–3457. doi: 10.1002/sim.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(16):9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125(1–2):279–284. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mocellin S, Verdi D, Pooley KA, Nitti D. Genetic variation and gastric cancer risk: a field synopsis and meta-analysis. Gut. 2015;64(8):1209–1219. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ijichi H, Ikenoue T, Kato N, Mitsuno Y, Togo G, Kato J, Kanai F, Shiratori Y, Omata M. Systematic analysis of the TGF-beta-Smad signaling pathway in gastrointestinal cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;289(2):350–357. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim T, Croce CM. Long noncoding RNAs: undeciphered cellular codes encrypting keys of colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2018;417:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu HN, Liu TT, Wu H, Chen YJ, Tseng YJ, Yao C, Weng SQ, Dong L, Shen XZ. Serum microRNA signatures and metabolomics have high diagnostic value in colorectal cancer by two novel methods. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:1185–1194. doi: 10.1111/cas.13514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong S, Chen Z, Xu J, Li W, Zhao J. Pre-mir-27a rs895819 polymorphism and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(4):3181–3186. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2392-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei EK, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Mantzoros CS. Low plasma adiponectin levels and risk of colorectal cancer in men: a prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(22):1688–1694. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gialamas SP, Petridou ET, Tseleni-Balafouta S, Spyridopoulos TN, Matsoukis IL, Kondi-Pafiti A, Zografos G, Mantzoros CS. Serum adiponectin levels and tissue expression of adiponectin receptors are associated with risk, stage, and grade of colorectal cancer. Metabolism. 2011;60(11):1530–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang QH, Peng HX, Zhang Y, Tian P, Xi ZL, Chen H. rs712 polymorphism within let-7 microRNA-binding site might be involved in the initiation and progression of colorectal cancer in Chinese population. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:3041–3045. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S89746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai Q, Wei HL, Huang J, Zhou TJ, Chai L, Yang ZH. KRAS polymorphisms are associated with survival of CRC in Chinese population. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(4):4727–4734. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamas K, Walenkamp AM, de Vries EG, van Vugt MA, Beets-Tan RG, van Etten B, de Groot DJ, Hospers GA. Rectal and colon cancer: not just a different anatomic site. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41(8):671–679. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui LH, Shin MH, Kweon SS, Kim HN, Song HR, Piao JM, Choi JS, Shim HJ, Hwang JE, Kim HR, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism in patients with gastric and colorectal cancer in a Korean population. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:236. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blount BC, Mack MM, Wehr CM, MacGregor JT, Hiatt RA, Wang G, Wickramasinghe SN, Everson RB, Ames BN. Folate deficiency causes uracil misincorporation into human DNA and chromosome breakage: implications for cancer and neuronal damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(7):3290–3295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi SW, Mason JB. Folate and carcinogenesis: an integrated scheme. J Nutr. 2000;130(2):129–132. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betticher DC, Thatcher N, Altermatt HJ, Hoban P, Ryder WD, Heighway J. Alternate splicing produces a novel cyclin D1 transcript. Oncogene. 1995;11(5):1005–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Govatati S, Singamsetty GK, Nallabelli N, Malempati S, Rao PS, Madamchetty VK, Govatati S, Kanapuram R, Narayana N, Bhanoori M, et al. Contribution of cyclin D1 (CCND1) and E-cadherin (CDH1) alterations to colorectal cancer susceptibility: a case–control study. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(12):12059–12067. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2505-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogino S, Wilson RB. Genotype and haplotype distributions of MTHFR677C>T and 1298A>C single nucleotide polymorphisms: a meta-analysis. J Hum Genet. 2003;48(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s100380300000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, Xu WL, Shen HL, Chen QY, Hui LL, Long LL, Zhu XL. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase genotypes and haplotypes associated with susceptibility to colorectal cancer in an eastern Chinese Han population. Genet Mol Res. 2011;10(4):3738–3746. doi: 10.4238/2011.December.14.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahmoudi T, Karimi K, Karimi N, Farahani H, Nobakht H, Dabiri R, Vahedi M, Zali MR. Association of adiponectin receptor 1 gene—106 C>T variant with susceptibility to colorectal cancer. Meta Gene. 2016;9:210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.mgene.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang WS, Tsou PL, Lee WJ, Tseng DL, Chen CL, Peng CC, Lee KC, Chen MJ, Huang CJ, Tai TY, et al. Allele-specific differential expression of a common adiponectin gene polymorphism related to obesity. J Mol Med. 2003;81(7):428–434. doi: 10.1007/s00109-002-0409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knudsen KE, Diehl JA, Haiman CA, Knudsen ES. Cyclin D1: polymorphism, aberrant splicing and cancer risk. Oncogene. 2006;25(11):1620–1628. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao L, Li K, Li W, Yang Z. Association between the C3435T polymorphism of ABCB1/MDR1 gene (rs1045642) and colorectal cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis based on 11,339 subjects. Tumour Biol. 2013;34(3):1949–1957. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Millar DS, Horan M, Chuzhanova NA, Cooper DN. Characterisation of a functional intronic polymorphism in the human growth hormone (GH1) gene. Hum Genomics. 2010;4(5):289–301. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-5-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Broderick P, Carvajal-Carmona L, Pittman AM, Webb E, Howarth K, Rowan A, Lubbe S, Spain S, Sullivan K, Fielding S, et al. A genome-wide association study shows that common alleles of SMAD7 influence colorectal cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2007;39(11):1315–1317. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu S, Zhou G, Zhang L, Jiang H, Xiao M. The effects of functional polymorphisms in the TGFbeta1 gene on nasopharyngeal carcinoma susceptibility. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(4):579–584. doi: 10.1177/0194599811434890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jazdzewski K, Murray EL, Franssila K, Jarzab B, Schoenberg DR, de la Chapelle A. Common SNP in pre-miR-146a decreases mature miR expression and predisposes to papillary thyroid carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(20):7269–7274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802682105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu Q, Liu JW, Yuan Y. Comprehensive assessment of the association between miRNA polymorphisms and gastric cancer risk. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2015;763:148–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffman AE, Zheng T, Yi C, Leaderer D, Weidhaas J, Slack F, Zhang Y, Paranjape T, Zhu Y. microRNA miR-196a-2 and breast cancer: a genetic and epigenetic association study and functional analysis. Cancer Res. 2009;69(14):5970–5977. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma G, Gu D, Lv C, Chu H, Xu Z, Tong N, Wang M, Tang C, Xu Y, Zhang Z, et al. Genetic variant in 8q24 is associated with prognosis for gastric cancer in a Chinese population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(4):689–695. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayashi H, Arao T, Togashi Y, Kato H, Fujita Y, De Velasco MA, Kimura H, Matsumoto K, Tanaka K, Okamoto I, et al. The OCT4 pseudogene POU5F1B is amplified and promotes an aggressive phenotype in gastric cancer. Oncogene. 2015;34(2):199–208. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kastler S, Honold L, Luedeke M, Kuefer R, Moller P, Hoegel J, Vogel W, Maier C, Assum G. POU5F1P1, a putative cancer susceptibility gene, is overexpressed in prostatic carcinoma. Prostate. 2010;70(6):666–674. doi: 10.1002/pros.21100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loo LW, Cheng I, Tiirikainen M, Lum-Jones A, Seifried A, Dunklee LM, Church JM, Gryfe R, Weisenberger DJ, Haile RW, et al. cis-Expression QTL analysis of established colorectal cancer risk variants in colon tumors and adjacent normal tissue. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e30477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kasagi Y, Oki E, Ando K, Ito S, Iguchi T, Sugiyama M, Nakashima Y, Ohgaki K, Saeki H, Mimori K, et al. The expression of CCAT2, a novel long noncoding RNA transcript, and rs6983267 single-nucleotide polymorphism genotypes in colorectal cancers. Oncology. 2017;92(1):48–54. doi: 10.1159/000452143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Detailed information of meta-analyses results for 25 high credibility significant associations. Table S2. Meta-analysis results: SNPs with non-significant associations to CRC risk.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.