Abstract

Background:

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAI-AP) for patients with schizophrenia (SCZ) have saved significant healthcare costs. However, the cost effectiveness of LAI-AP for patients with other mental disorders has yet to be established. The goal of this study was to evaluate the impact of early initiation of LAI-AP medications on healthcare resource utilization (HRU). Drawing on the Quebecois universal healthcare program (RAMQ), we conducted a nationwide prospective cohort study of LAI-AP under real-world conditions.

Methods:

This study was performed using a representative sample of patients newly treated with LAI-AP (n = 3957) who were covered by the Québec Health Insurance Plan. The index date was defined as the date of the first prescription for LAI-AP between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2012. We collected (a) the demographics and patient characteristics; (b) the treatment characteristics index drug, speciality of the principal prescriber, prescriptions of LAI-AP; and (c) HRU and costs. Two comparisons were made between (a) non-SCZ users of LAI-AP and SCZ users of LAI-AP; and (b) patients with SCZ using first-generation antipsychotic LAI-AP (FGA-LAI) and second-generation antipsychotic LAI-AP (SGA-LAI).

Results:

In the people with SCZ group, 976 patients were on an SGA-LAI, and 1020 patients were on an FGA-LAI; 41.9% of all users were on risperidone LAI-AP during this period and 17.9% were on zuclopenthixol decanoate. The number of hospitalizations was reduced by half. Durations were also significantly reduced. The total healthcare cost savings for all users were C$29,876 per patient/per year. Younger patients tended to receive more SGA-LAI than FGA-LAI: 29% versus 13%. The percentage of general practitioners who prescribe LAI-AP is higher in the FGA-LAI group than in the SGA-LAI group: 19% versus 13%. For psychiatrist prescribers, it is the opposite: 86% (SGA-LAI) versus 79% (FGA-LAI). The concomitant use of oral antipsychotics (OAP) in the year following index date is higher in the FGA-LAI group: 75% versus 43%. The number of hospitalization days was reduced by 31.5 days in the FGA-LAI group and 38.8 days in the SGA-LAI group. Cost savings were of C$31,924 in the FGA-LAI group and of C$39,100 in the SGA-LAI group.

Conclusion:

The initiation of LAI-AP saved significant costs to the province of Québec compared with the previous year. Initiation of a LAI-AP resulted in lower resource use. Higher medication costs were offset by lower inpatient and outpatient costs.

Keywords: antipsychotics, compliance, healthcare resource utilization, long-acting injection formulations of antipsychotics, relapse prevention, schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia

Introduction

A number of studies using various methodologies have investigated the relative effectiveness of oral antipsychotics (OAPs) and long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAI-APs). These include randomized controlled trials (RCTs), naturalistic, prospective or retrospective cohort studies and mirror-image designs.1–3 Database studies and recent RCTs have evidenced more favorable outcomes with LAI-APs over OAPs in the early phase of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder (SCZ), including adherence to treatment, hospitalizations, and relapse prevention.4–7 In a recent study, we illustrated that healthcare costs in the year following LAI-AP initiation in SCZ were associated with significant healthcare cost savings compared with the previous year.8–11 Drawing on the Québec universal healthcare program (RAMQ) that covers physician services and hospitalizations for the entire province of Québec, our study focused only on a population of patients with SCZ and schizoaffective disorder (n < 2000). However, upon exploring the dataset, we noticed a substantial number of patients with other diagnoses receiving LAI-APs during the same period of time. This additional group included patients who received ICD-9 diagnoses of: other psychotic disorders, 297.0–298.9; bipolar disorder, 296.x; major depressive disorder, 311.x; anxiety disorders, 293.0, 293.9, 300.0, 300.9, 308.x; and substance-use disorders, 291.0, 292.9, 303.0-305.9. In evidence-based medicine (EBM), there are a lack of data on the use of LAI-APs in psychiatric conditions other than SCZ. This includes guidelines, meta-analysis, expert opinion and consensus forums. In practice-based medicine (PBM), what we see is a large use of LAI-APs in psychotic conditions, but with an affective feature: bipolar disorder, delusional disorder, substance-induced psychosis, borderline or antisocial personality disorder. In a recent cohort with more than 29,000 patients, a large amount of prescriptions of LAI-APs were used to treat mood disorders.7

In this article, we present results for all users of LAI-APs in Québec (n < 4000). In addition, we compare the effectiveness of first-generation antipsychotics (FGA-LAIs) to second-generation antipsychotics (SGA-LAIs) on healthcare resource utilization and costs (HRU), including antipsychotics that have been recently approved in Canada.

Methods

Database

Québec is the second most populous province of Canada, following Ontario. In the 2016 census, Québec had a population of 8,164,361. Canada is a federation in which each province is responsible for their healthcare program, except for aboriginal people and Northern territories, where the federal government is directly involved. In Québec, the RAMQ covers physician services and hospitalizations for the whole population. This universal health program is complemented by a public drug plan. This provincial drug reimbursement program covers all people aged 65 and over, beneficiaries of the social assistance program, and individuals who do not have access to a private medication insurance plan. Most patients with SCZ or chronic psychosis are included in this plan. As opposed to the healthcare plan, for which all costs are covered, the drug plan involves limited financial participation on the part of beneficiaries. The RAMQ medical services database contains information from physicians’ claims for services provided within and outside the hospital. The RAMQ pharmaceutical services database includes information from pharmacists’ claims for dispensed medication reimbursed by the program but not for medication received in a hospital.

Review boards linked to the Ministry of Health agreed to deliver the dataset. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Québec Health Insurance Board (Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec, RAMQ). The RAMQ is a government agency that is responsible for the coding and anonymization of patient data, and already provides strict control to deliver anonymous data to researchers for specific research questions. As such, the RAMQ is inherently responsible for ethics and confidentiality. Therefore, ethical approval is considered to be granted upon the provision of their data. In this context in Québec, an approval from any another ethical board was not necessary. The data obtained from the RAMQ include an encrypted patient identifier, which enables linkage of individual patient information while preserving anonymity. The RAMQ database also includes information on the insured person, such as age, sex, and region, and information on the physicians.

Patient selection

Data on medical and pharmaceutical services were originally obtained from the RAMQ database for patients who had received at least prescription of an LAI-AP between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2012.8 The index date was defined as the date of the first prescription for an LAI-AP between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2012, and the index drug was defined as the first drug of LAI-AP prescribed in this period. Data on medical and pharmaceutical services were available 1 year before and 1 year after the index date. Patients had to be incident users of LAI-APs for 12 months prior to the index date. Noneligibility included patients with no continuous enrolment in the database for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date.

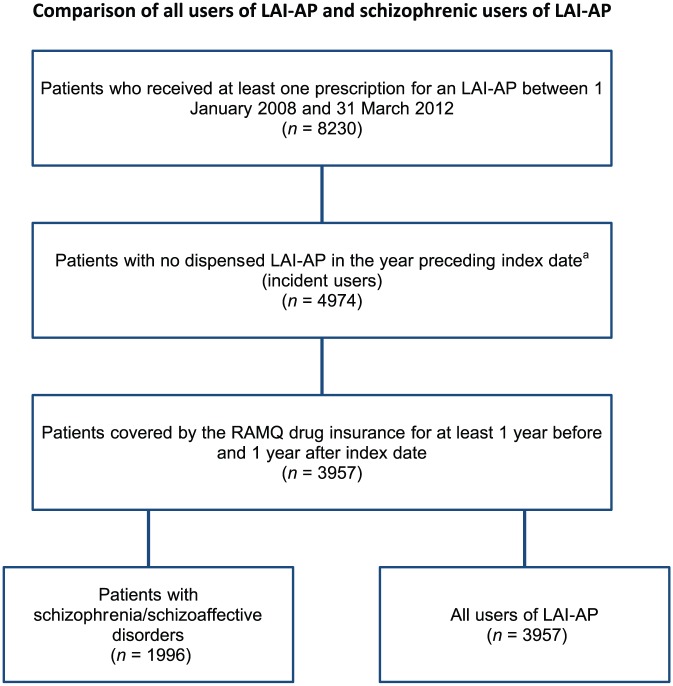

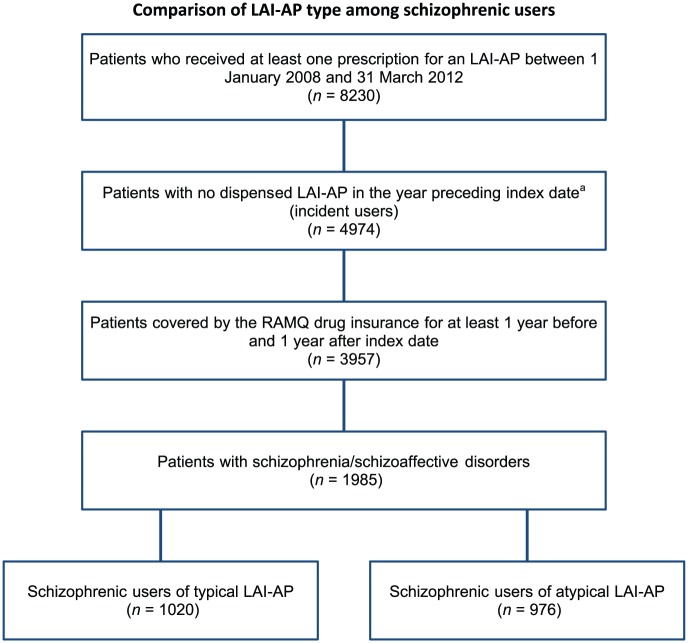

Two comparisons were made between: (a) non-SCZ users of LAI-APs and SCZ users of LAI-APs; and (b) patients with SCZ using FGA-LAIs and SGA-LAIs. Patients were considered SCZ users if the last diagnosis related to psychiatric diseases (ICD-9 codes 290.0–311.9) recorded in the database was a diagnosis of SCZ (ICD-9 code 295.x). Patients were considered users of FGA-LAI if their index drug was a prescription of haloperidol decanoate, fluphenazine decanoate, zuclopenthixol decanoate or flupentixol decanoate, and users of SGA-LAI if their index drug was a prescription of risperidone long-acting injection or paliperidone long-acting injection (PLAI). At the time of collecting the data, (2008–2012), PLAI was just recently approved, aripiprazole long-acting injection was under submission and PP3M paliperidone not yet submitted. Consequently, the number of patients prescribed with these recent formulations is either lower or absent (Figure 1 & 2).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the selection of all and schizophrenic users of long-acting injectable antipsychotics.

aThe index date was defined as the date of the first prescription for LAI-AP between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2012.

LAI-AP, long-acting injectable antipsychotic; RAMQ, Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the selection of schizophrenic users of typical and atypical long-acting injectable antipsychotics.

aThe index date was defined as the date of the first prescription for LAI-AP between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2012.

LAI-AP, long-acting injectable antipsychotic; RAMQ, Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec.

Data collection

We collected (a) the demographics and patients characteristics: age, sex, geographic location, medical history and (b) the treatment characteristics index drug, speciality of the principal prescriber, prescriptions of LAI-APs (prescription of OAP, prescriber of the index drug, speciality, location of dispensation), and (c) HRU and costs were estimated in terms of: number and cost of hospitalizations, number and cost of intensive care unit (ICU) visits, number and cost of emergency department visits, number and cost of outpatient visits, and number and cost of medications.

The medical services and prescription claims were categorized into all psychiatric-related (ICD-9 codes 290.0–311.9) and SCZ-related (ICD-9 code 295.x) HRU. There was a variety of prescription requests classified as psychiatrically related. Prescription claims categorized as SCZ related were LAI-APs and OAPs. Psychiatric and SCZ HRU were not mutually exclusive. SCZ diagnosis was a subgroup of psychiatric-related diagnoses, and SCZ medications were a subgroup of psychiatric-related medications.

Number and cost of hospitalizations and ICU visits

The number of inpatient admissions and lengths of stay are not directly available in the RAMQ database. In order to estimate the admissions and inpatient stays, we counted the number of RAMQ medical claims, assessed the reported location for the medical activity and the time between two consecutive inpatient claims.8 We classified only-one-inpatient-visit cases where the claims had the same date and the same physician, and if the time between two consecutive claims was 7 days or less. The cost of inpatient admissions was estimated by using the average daily cost of inpatient visit in 2012 (C$984 for hospitalization and C$1090.10 for a ICU visit)9 in addition to the cost of the services directly taken from the medical services database of the RAMQ.

Number and cost of emergency department visits

The number of visits to an emergency room was obtained from the medical services database of the RAMQ according to the reported location for the medical activity. In cases where the claims had the same date and the same physician, we classified this as one inpatient visit. The cost of an emergency room visit was estimated using the average cost for an emergency room visit in 2012 (C$161.38)8 in addition to the cost of the services directly taken from the medical services database of the RAMQ.

Number and cost of outpatient visits

The number of physicians’ visits was obtained from the medical services database of the RAMQ according to the reported location for the medical activity and includes general practitioners’ (GPs) and specialists’ visits. We accounted only one inpatient visit if the claims had the same date and the same physician. The cost of visits and procedures were directly taken from the medical services database of the RAMQ.

Number and cost of medications

The number and cost of medications were estimated based on the claims provided from the pharmaceutical services database of the RAMQ. The cost of medications excluded the pharmacist fees and wholesaler upcharge.

Statistical analysis

The HRU was estimated for both periods (i.e. pre-, and postinitiation); that is, 1 year prior to and 1 year following the initiation periods. Paired-sample t tests were conducted to compare these periods for continuous variables, while chi-square tests were used for categorical variables. The variables considered in this study were the occurrence of hospitalization, and of the other resources. Measures of central tendency and variability [mean, standard deviation (SD)] were used to describe the number of days of hospitalizations, of emergency room visits for psychiatric reasons, of partial hospitalizations for psychiatric reasons, of visits to the psychiatrist, and of other office visits. The results of the inpatient and outpatient resources were presented for all patients. The statistical tests were two tailed with an alpha level of 0.05. With reference to the central limit theorem, tests of normal distribution were not performed, given the large sample size used in this study.

Measures of central tendency and variability (mean, SD) were used to describe the total costs incurred by the users in both pre- and postinitiation periods. Total costs included total inpatient costs, total outpatient costs, and total medication costs. These costs were estimated using the average daily cost of hospitalization reported by the Québec Hospital Association. Costs were reported in Canadian dollars (C$). For the comparison of FGA and LAI, as well as SGA-LAI, chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and independent t tests were used for continuous variables. In addition, in each presented table of this article statistical tests used for group comparison are documented in the legend: p value is from chi-square test unless stated otherwise, and p value from Fisher’s exact test.

Results

We found that 3957 patients treated with antipsychotics were covered by the RAMQ drug insurance for at least 1 year before and 1 year after index date. The mean age was similar between all users of the LAI-AP group and SCZ group [Table 1(a)]. In the SCZ group, 976 patients were on an SGA-LAI, and 1020 patients were on an FGA-LAI. Out of all users, 41.9% were on risperidone LAI-AP during this period, 15.4% of SCZ were prescribed clozapine combined with LAI-AP, 17.9% were on zuclopenthixol [Table 1(b)]. Out of all prescribers, 80% were psychiatrists and 19%, GPs. We observed that the concomitant use of OAPs in the following year remained at 62% for SCZ and 54 % for all users. The number of hospitalizations was reduced by half. Their duration also significantly decreased. The total healthcare cost savings for all users were C$29,876 which is approximately US$23,300, €20,069 and £17,748 per patient (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics and treatment characteristics for all schizophrenic users of long-acting injectable antipsychotics.

| (a) Demographic and clinical characteristics | All users of LAI-AP (n = 3957) |

Schizophrenic users of

LAI-AP (n = 1996) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics at index datea | ||

| Age groups, years, n (%) | ||

| <30 | 956 (24.2) | 423 (21.2) |

| 30–39 | 856 (21.6) | 437 (21.9) |

| 40–49 | 788 (19.9) | 424 (21.2) |

| 50–59 | 771 (19.5) | 424 (21.2) |

| >60 | 586 (14.8) | 288 (14.4) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 42.8 (15.4) | 43.4 (14.5) |

| Men, n (%) | 2499 (63.2) | 1314 (65.8) |

| Comorbidities in the year preceding index date | ||

| Mental disorders, n (%) | ||

| Bipolar disorder | 1285 (32.5) | 646 (32.4) |

| Major depressive disorder | 656 (16.6) | 341 (17.1) |

| Anxiety disorders | 1909 (48.2) | 966 (48.4) |

| Substance-use disorders | 939 (23.7) | 474 (23.7) |

| Other psychotic disorders | 1706 (43.1) | 866 (43.4) |

| (b) Treatment characteristics | All users of LAI-AP (n = 3957) |

Schizophrenic users of

LAI-AP (n = 1996) |

| Index drug,a n (%) | ||

| First-generation LAI | ||

| Risperidone LAI | 1658 (41.9) | 775 (38.8) |

| Paliperidone LAI | 396 (10.0) | 201 (10.1) |

| Second-generation LAI | ||

| Haloperidol decanoate | 339 (8.6) | 201 (10.1) |

| Fluphenazine decanoate | 661 (16.7) | 353 (17.7) |

| Zuclopenthixol decanoate | 707 (17.9) | 355 (17.8) |

| Flupentixol decanoate | 196 (5.0) | 111 (5.6) |

| Treatment characteristics of LAI-AP in the year following index dateb | ||

| Speciality of the principal prescriber, n (%) | ||

| Psychiatry | 3167 (80.0) | 1656 (83.0) |

| General practice | 761 (19.2) | 332 (16.6) |

| Other | 24 (0.6) | 7 (0.4) |

| Not available | 5 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Number of prescriptions of LAI-AP per patient, mean (SD) | ||

| All LAI-APs | 13.2 (8.9) | 13.5 (8.9) |

| First-generation LAI-APs | 8.5 (10.3) | 8.4 (10.4) |

| Second-generation LAI-APs | 4.7 (7.0) | 5.1 (7.1) |

| Concomitant use of OAP in the year following index date | ||

| Number of prescriptions of OAP per patient, mean (SD) | ||

| All OAP | 30.0 (54.1) | 32.9 (61.9) |

| First-generation OAP | 4.0 (19.7) | 4.9 (25.0) |

| Second-generation OAP | 26.0 (46.5) | 28.0 (50.9) |

| Clozapine | 2.9 (15.4) | 3.9 (18.6) |

| Characteristics of the prescriber of the index drug, n (%) | ||

| Speciality | ||

| Psychiatry | 3102 (78.4) | 1603 (80.3) |

| General practice | 818 (20.7) | 380 (19.0) |

| Other | 28 (0.7) | 9 (0.5) |

| Not available | 9 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) |

| Dispensing location | ||

| Inpatient | 362 (9.1) | 215 (10.8) |

| Emergency department | 80 (2.0) | 43 (2.2) |

| Psychiatric department | 1244 (31.4) | 613 (30.7) |

| Outpatient | 1308 (33.1) | 710 (35.6) |

| Private clinic | 252 (6.4) | 127 (6.4) |

| Other | 40 (1.0) | 8 (0.4) |

| Not available | 671 (17.0) | 280 (14.0) |

The index drug was defined as the first LAI-AP prescribed between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2012.

The index date was defined as the date of the first prescription for LAI-AP between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2012.

LAI-AP, long-acting injectable antipsychotic; OAP, oral antipsychotic.

Table 2.

Healthcare services utilization and costs in the year preceding and year following index date for all and schizophrenic users of long-acting injectable antipsychotics.

| Healthcare services utilization and costs in the year preceding and the year following index date,a mean (SD) | All users of

LAI-AP (n = 3957) |

Schizophrenic users of

LAI-AP (n = 1996) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year preceding index date | Year following index date |

p value (95% CI)b |

Year preceding index date | Year following index date |

p value (95% CI)b |

|

| All services | ||||||

| Number of healthcare services per patient | ||||||

| Hospitalizations | 1.8 (2.2) | 0.9 (1.6) | 0.00 (0.9; 1.0) |

2.0 (2.3) | 0.9 (1.8) | 0.00 (0.9; 1.1) |

| Hospitalization days | 48.0 (63.5) | 16.4 (39.0) | 0.00 (29.5; 33.7) |

52.4 (66.6) | 17.3 (40.3) | 0.00 (32.0; 38.2) |

| ICU visits | 0.0 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.00 (0.0; 0.0) |

0.0 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.00 (0.0; 0.0) |

| ICU days | 0.3 (3.1) | 0.1 (1.4) | 0.00 (0.1; 0.3) |

0.4 (4.1) | 0.1 (1.3) | 0.00 (0.1; 0.4) |

| Emergency department visits | 5.2 (7.6) | 3.1 (6.4) | 0.00 (1.8; 2.3) |

5.0 (7.1) | 3.1 (5.9) | 0.00 (1.6; 2.3) |

| Outpatient visits | 3.3 (5.6) | 3.4 (6.3) | 0.28 (−0.2; 0.1) |

3.2 (5.5) | 3.4 (6.4) | 0.12 (−0.3; 0.0) |

| Psychiatric department visits | 5.2 (7.4) | 8.4 (10.0) | 0.00 (−3.6; −3.0) |

5.4 (7.5) | 8.7 (10.3) | 0.00 (−3.7; −2.9) |

| All medical services | 15.5 (13.4) | 15.8 (14.7) | 0.16 (−0.7; 0.1) |

15.7 (13.1) | 16.2 (14.7) | 0.13 (−1.0; 0.1) |

| Prescriptions drug | 111.9 (184.2) | 160.8 (228.0) | 0.00 (−53.7; −44.0) |

113.0 (181.7) | 165.1 (239.8) | 0.00 (−59.4; −44.8) |

| All healthcare services | 127.4 (187.2) | 176.6 (230.7) | 0.00 (−54.0; −44.3) |

128.7 (184.0) | 181.3 (242.5) | 0.00 (−59.9; −45.2) |

| Healthcare services cost per patient | ||||||

| Hospitalization cost | 49,084 (64,533) | 16,889 (39,958) | 0.00 (30,070; 34,321) |

53,482 (67,586) | 17,786 (41,193) | 0.00 (32,557; 38,834) |

| ICU cost | 347 (3544) | 158 (1660) | 0.00 (75; 304) |

428 (4622) | 132 (1500) | 0.00 (96; 497) |

| Emergency department cost | 1363 (1967) | 822 (1684) | 0.00 (479; 603) |

1,332 (1856) | 807 (1541) | 0.00 (439; 611) |

| Outpatient cost | 209 (386) | 221 (456) | 0.03 (−23; −1) |

203 (373) | 220 (442) | 0.03 (−33; −2) |

| Psychiatric department cost | 445 (636) | 771 (855) | 0.00 (−350; −301) |

456 (638) | 776 (852) | 0.00 (−355; −285) |

| All medical cost | 51,448 (65,278) | 18,861 (40,854) | 0.00 (30,441; 34,734) |

55,900 (68,427) | 19,721 (41,994) | 0.00 (33,005; 39,352) |

| Prescription drug cost | 1814 (2544) | 4525 (3880) | 0.00 (−2819; −2603) |

1889 (2547) | 4,591 (3886) | 0.00 (−2860; −2544) |

| Total healthcare cost | 53,262 (64,968) | 23,386 (40,801) | 0.00 (27,759; 31,994) |

57,790 (68,066) | 24,313 (41,884) | 0.00 (30,347; 36,607) |

The index date was defined as the date of the first prescription for LAI-AP between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2012.

p value and 95% CI from paired t test of the comparison of mean for the year preceding and the year following index date.

CI, confidence interval; LAI-AP, long-acting injectable antipsychotic; ICU, intensive care unit; SD, standard deviation.

Statistically significant differences were found between the two groups of SCZ patients prescribed with LAI-APs. Younger patients tended to receive more SGA-LAIs than FGA-LAIs, where FGA-LAI (mean = 136, SD = 13.3) and SGA-LAI (mean = 287, SD = 29.4) p = 0.00 (Table 3). Contrary to this, after the age of 40, SCZ patients receive significantly more FGA-LAIs than SGA-LAIs. The percentage of GPs who prescribe LAI-APs is higher in the FGA-LAIs than in the SGA-LAIs: 20% versus 13% p = 0.00 (Table 4). However, among psychiatrists, percentages reflected a higher rate, in which 86.6% prescribe SGA-LAIs versus 79.5% who prescribe FGA-LAIs, p = 0.00. The concomitant use of OAPs in the year following index date is higher in the FGA-LAI group: 75.7% versus 43%, p = 0.00. The number of hospitalization days was reduced by 31.5 days in the FGA-LAI group and 38.8 days in the SGA-LAI group (Table 5). Cost savings were of C$31,924 in the FGA-LAI group and of C$35,100 in the SGA-LAI group.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics for schizophrenic users of first-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics and second-generation long-acting antipsychotics.

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | Schizophrenic users of

FGA-LAI (n = 1020) |

Schizophrenic users of

SGA-LAI (n = 976) |

p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics at index dateb | |||

| Age groups, years, n (%) | |||

| <30 | 136 (13.3) | 287 (29.4) | 0.00 |

| 30–39 | 183 (17.9) | 254 (26.0) | 0.00 |

| 40–49 | 238 (23.3) | 186 (19.1) | 0.02 |

| 50–59 | 276 (27.1) | 148 (15.2) | 0.00 |

| >60 | 187 (18.3) | 101 (10.3) | 0.00 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 46.9 (13.9) | 39.7 (14.2) | 0.00 |

| Men, n (%) | 647 (63.4) | 667 (68.3) | 0.02 |

p value from chi-square test unless stated otherwise.

The index date was defined as the date of the first prescription for LAI-AP between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2012.

p value from Fisher’s exact test.

FGA-LAI, first-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotic; SD, standard deviation; SGA-LAI, second-generation long-acting antipsychotic.

Table 4.

Treatment characteristics for schizophrenic users of first-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics and second-generation long-acting antipsychotics.

| Treatment characteristics | Schizophrenic users of

FGA-LAI (n = 1020) |

Schizophrenic users of

SGA-LAI (n = 976) |

p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment characteristics of the index drug,b n (%) | |||

| First-generation LAI | |||

| Haloperidol decanoate | 201 (19.7) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Fluphenazine decanoate | 353 (34.6) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Second-generation LAI | |||

| Risperidone LAI | 0 (0.0) | 775 (79.4) | – |

| Paliperidone LAI | 0 (0.0) | 201 (20.6) | – |

| Zuclopenthixol decanoate | 355 (34.8) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Flupentixol decanoate | 111 (10.9) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Treatment characteristics of LAI-AP in the year following index date | |||

| Speciality of the principal prescriber, n (%) | |||

| Psychiatry | 811 (79.5) | 845 (86.6) | 0.00 |

| General practice | 203 (19.9) | 129 (13.2) | 0.00 |

| Other | 6 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 0.13* |

| Not available | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0.49* |

| Concomitant use of oral antipsychotics in the year following index date | |||

| Number of prescriptions of OAP per patient, mean (SD) | |||

| All OAP | 34.7 (75.7) | 31.0 (43.1) | 0.18 |

| First-generation OAP | 6.6 (31.8) | 3.2 (14.8) | 0.00 |

| Second-generation OAP | 28.1 (60.2) | 27.9 (39.0) | 0.93 |

| Clozapine | 3.8 (21.4) | 3.9 (15.3) | 0.91 |

| Characteristics of the prescriber of the index drug, n (%) | |||

| Speciality | |||

| Psychiatry | 777 (76.2) | 826 (84.6) | 0.00 |

| General practice | 236 (23.1) | 144 (14.8) | 0.00 |

| Other | 5 (0.5) | 4 (0.4) | 1.00* |

| Not available | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1.00* |

| Dispensing location | |||

| Inpatient | 82 (8.0) | 133 (13.6) | 0.00 |

| Emergency department | 22 (2.2) | 21 (2.2) | 0.99 |

| Psychiatric department | 260 (25.5) | 353 (36.2) | 0.00 |

| Outpatient | 397 (38.9) | 313 (32.1) | 0.00 |

| Private clinic | 112 (11.0) | 15 (1.5) | 0.00 |

| Other | 5 (0.5) | 3 (0.3) | 0.73* |

| Not available | 142 (13.9) | 138 (14.1) | 0.89 |

p value from chi-square test unless stated otherwise.

The index drug was defined as the first LAI-AP prescribed between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2012.

p value from Fisher’s exact test.

LAI, long-acting injectable; FGA-LAI, first-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotic; LAI-AP, long-acting injectable antipsychotic; OAP, oral antipsychotic; SD, standard deviation; SGA-LAI, second-generation long-acting antipsychotic.

Table 5.

Healthcare services utilization and costs in the year preceding and year following index date for schizophrenic users of first-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics and second-generation long-acting antipsychotics.

| Healthcare services utilization and costs in the year preceding and year following index date,a mean (SD) | Schizophrenic users of

FGA-LAI (n = 1020) |

Schizophrenic users of

SGA-LAI (n = 976) |

Comparison of schizophrenic users of

FGA-LAI and SGA-LAI |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year preceding index date | Year following index date |

p value (95% CI)b |

Year preceding index date | Year following index date |

p value (95% CI)b |

p valuec | p valued | |

| All services | ||||||||

| Number of healthcare services per patient | ||||||||

| Hospitalizations | 1.8 (2.5) | 0.9 (2.0) | 0.00 (0.7; 1.0) |

2.1 (2.1) | 0.9 (1.5) | 0.00 (1.0; 1.3) |

0.01 | 0.97 |

| Hospitalization days | 46.7 (68.9) | 15.2 (36.9) | 0.00 (27.3; 35.8) |

58.3 (63.6) | 19.5 (43.4) | 0.00 (34.3; 43.3) |

0.00 | 0.02 |

| ICU visits | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.00 (0.0; 0.1) |

0.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.17 (−0.0; 0.0) |

0.09 | 0.78 |

| ICU days | 0.5 (5.3) | 0.1 (1.4) | 0.01 (0.1; 0.7) |

0.2 (2.1) | 0.1 (1.1) | 0.19 (−0.0; 0.2) |

0.08 | 0.94 |

| Emergency department visits | 4.5 (7.1) | 3.0 (6.1) | 0.00 (1.0; 1.9) |

5.6 (6.9) | 3.1 (5.6) | 0.00 (2.0; 2.9) |

0.00 | 0.74 |

| Outpatient visits | 3.7 (5.6) | 3.9 (5.8) | 0.07 (−0.5; 0.0) |

2.8 (5.3) | 2.8 (6.8) | 0.62 (−0.4; 0.2) |

0.00 | 0.00 |

| Psychiatric department visits | 4.8 (6.7) | 7.1 (8.6) | 0.00 (−2.8; −1.9) |

6.1 (8.1) | 10.4 (11.5) | 0.00 (−5.0; −3.6) |

0.00 | 0.00 |

| All medical services | 14.9 (12.6) | 15.0 (13.5) | 0.68 (−0.9; 0.6) |

16.6 (13.5) | 17.3 (15.9) | 0.09 (−1.6; 0.1) |

0.00 | 0.00 |

| Drug prescriptions | 125.9 (188.3) | 185.7 (285.4) | 0.00 (−71.8; −47.9) |

99.5 (173.7) | 143.6 (177.7) | 0.00 (−52.1; −36.0) |

0.00 | 0.00 |

| All healthcare services | 140.7 (190.4) | 200.7 (287.7) | 0.00 (−72.0; −47.9) |

116.1 (176.3) | 160.9 (181.7) | 0.00 (−53.0; −36.7) |

0.00 | 0.00 |

| Healthcare services cost per patient, C$ | ||||||||

| Hospitalization cost | 47,503 (69,718) | 15,547 (37,613) | 0.00 (27,668; 36,244) |

59,730 (64,731) | 20,127 (44,527) | 0.00 (35,013; 44,194) |

0.00 | 0.01 |

| ICU cost | 597 (5952) | 133 (1673) | 0.01 (109; 819) |

251 (2575) | 130 (1296) | 0.18 (−54; 296) |

0.09 | 0.97 |

| Emergency department cost | 1169 (1859) | 774 (1576) | 0.00 (279; 512) |

1,503 (1839) | 843 (1505) | 0.00 (534; 786) |

0.00 | 0.32 |

| Outpatient cost | 211 (357) | 241 (400) | 0.00 (−49; −10) |

193 (389) | 199 (482) | 0.66 (−29; 19) |

0.28 | 0.03 |

| Psychiatric department cost | 368 (509) | 613 (700) | 0.00 (−285; −206) |

548 (739) | 946 (958) | 0.00 (−455; −341) |

0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total medical cost | 49,848 (70,952) | 17,307 (38,543) | 0.00 (28,193; 36,889) |

62,225 (65,123) | 22,244 (45,203) | 0.00 (35,352; 44,610) |

0.00 | 0.01 |

| Prescription drugs cost | 1919 (2500) | 2535 (2729) | 0.00 (−754; −479) |

1858 (2597) | 6740 (3751) | 0.00 (−5098; −4665) |

0.59 | 0.00 |

| Total healthcare cost | 51,767 (70,648) | 19,843 (38,596) | 0.00 (27,612; 36,238) |

64,084 (64,698) | 28,984 (44,609) | 0.00 (30,547; 39,651) |

0.00 | 0.00 |

The index date was defined as the date of the first prescription for LAI-AP between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2012.

p value and 95% CI from paired t test of the comparison of mean for the year preceding and the year following index date.

p value from independent t test of the comparison of mean in the year preceding index date for schizophrenic users of first-generation antipsychotics and second-generation LAI-AP.

p value from independent t test of the comparison of mean in the year following index date for schizophrenic users of first-generation antipsychotics and second-generation LAI-AP.

CI, confidence interval; FGA-LAI, first-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotic; ICU, intensive care unit; LAI-AP, long-acting injectable antipsychotic; SD, standard deviation; SGA-LAI, second-generation long-acting antipsychotic.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to evaluate the cost effectiveness of LAI-APs among all patients in Québec under real-world conditions. We analyzed data from 1 January 2008 to 31 March 2012 in almost 4000 patients with SCZ and other psychotic disorders treated with LAI-APs. Our results are in concordance with Tiihonen and colleague’s7 results with the Scandinavian cohort. The main outcomes are the decrease on hospitalizations and the reduction of their duration. Consequently, healthcare costs in the year following LAI-AP initiation were associated with significant healthcare cost savings compared with the previous year.

The combination of clozapine with LAI-AP was not uncommon (more than 10%). Clozapine with LAI-AP is considered a good combination; however, in our short-term study, the addition of risperidone to clozapine did not improve symptoms in patients with severe SCZ.12 Clozapine and LAI-AP are associated with the lowest risk for relapse and rehospitalization among patients with SCZ. The reason our findings on clozapine differ might be the result of a naturalistic augmentation therapy of LAI-AP. This may also be an indication to take precautionary measures with patients who discontinue their clozapine treatment abruptly. In this instance, LAI-APs may be protective against relapse. Alternatively, it may be due to either the maximum dosage of clozapine if it is already very high and cannot be increased, or to decrease the side effects of a specific dosage.

A treatment algorithm from Quebec13 recommends as a first-line choice, the use of LAI-APs in patients with SCZ, schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorder. SGA-LAI can also be used after a first episode of SCZ. They can be considered as a second-line option to prevent manic recurrence or in combination with mood stabilizers to prevent depressive recurrence in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. They are considered as a first-line option for maintenance treatment in SCZ. We are currently revisiting the algorithm and these data will have a profound impact on our updated study.

This study is like a photograph that one takes of oneself, a ‘selfie’. Being the prescribers in Québec, we must recall that patients are not in a clinical experimental protocol. They are regular patients. In this context, it is crucial to question some of our results: why do we continue prescribing OAPs 1 year following the introduction of LAI-AP? Did we simply forget to stop using the older-generation antipsychotic? Did we need the oral medication to produce a combined effect to enhance the LAI-AP antipsychotic action? Or was the LAI-AP effect insufficient? Are the cost savings sufficiently well considered? What does it mean in terms of politics? How do we include these in a new vision of mental illness, progress in patients’ rights and aspirations, and shared decision, given that a large group of patients is probably noncompliant and under the law for treatment order? Is the place of health costs recently really taken into consideration? These real-world results are also based on the indications of LAI-APs, that is, stabilized patients for whom the challenge is rehabilitation care and recovery, more than the control of symptoms. Prescription of LAI-APs should be associated with intervention strategies aimed at promoting medication adherence.12,13 In fact, Verdoux and colleagues conducted a study in a representative sample of 6904 persons newly treated with OAPs affiliated to the French Insurance Healthcare system.14 The authors found that in spite of the rate of ambulatory treatment, discontinuation is less frequent than with OAPs; there is still a high rate with LAI-APs.

Limitations

A few limitations have been considered during interpretation of the results. In Québec, physicians are not required to record an ICD-9 code, and only one code can be recorded. The DSM-5 criteria are applied in this study, however, we note that diagnoses were not always well recorded in the database. Consequently, there is likely a discrepancy between the best and accurate diagnosis and the diagnosis in the RAMQ data set. We decided to account for this gap by examining not only the SCZ group, but all users. Furthermore, the direct costs reported in our study were estimations (from average daily costs reported by the Québec Hospital Association). Results are limited to comparisons of patients who were previously prescribed OAPs prior to treatment of LAI-APs, as poor outcome of OAP treatment is often followed by treatment with LAI-AP. Therefore, there is a need for future studies to examine the combined treatment of OAP and LAI-AP across other nations.

Given new developments in medication and classification criteria during the data collection period we are currently working toward a new analysis spanning a longer length of time, in which data from 2017 is included. Also, this study did not investigate and account for the reasons that older patients received relatively more FGA-LAIs than younger patients. This can be considered in future research studies in order to enrich findings.

Conclusion

For almost 4000 users of antipsychotic medication, initiation of a LAI-APs resulted in lower resource use and overall, lower associated costs. Higher medication costs were offset by lower inpatient and outpatient costs. These new results are very similar to our previous findings where only SCZ is considered in the analysis. The conclusions of this article are consistent with past findings in that LAI-APs save healthcare costs. Further analysis is recommended to explore the effect of LAI-APs over a longer period of time and with the new medication, including formulation that leads to longer intervals between injections.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by Lundbeck Canada Inc. and Otsuka Canada Pharmaceutical Inc. Since the acceptation of the article Emmanuel Stip received fees for lecturing from Jannssen, Canada, France, Belgium and from Lunbeck-Otsuka Canada on this topic. Jean Lachaine has received financial support for research projects from Lundbeck and Otsuka.

Conflict of interest statement: Emmanuel Stip declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Emmanuel Stip, Département de Psychiatrie, Université de Montréal Faculté de Médecine, C.P. 6128, Succursale Centre-Ville, Montréal, Québec H3C 3J7, Canada.

Jean Lachaine, CR-CHUM, University of Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada.

References

- 1. Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, et al. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012; 379: 2063–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Nitta M, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of prospective and retrospective cohort studies. Schizophr Bull 2017; 44: 603–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fakra E, Azorin JM, Belzeaux R, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of long acting injectable antipsychotics through clinical trials. Encephale 2016; 42: S43–S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tiihonen J, Haukka J, Taylor M, et al. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2011; 168: 603–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry 2016; 77(Suppl. 3): 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Citrome L, Levine J, Allingham B. Utilization of depot neuroleptic medication in psychiatric inpatients. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996; 32: 321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Majak M, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 29 823 patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74: 686–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lachaine J, Lapierre ME, Abdalla N, et al. Impact of switching to long-acting injectable antipsychotics on health services use in the treatment of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 2015; 60(Suppl. 2): S40–S47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stip E. Cost reductions associated with long-acting injectable antipsychotics according to patient age. J Clin Psychiatry 2017; 78: e1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stip E. Physician characteristics associated with prescription of long-acting injectable antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2017; 78: e1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. Dr Correll and colleagues reply. J Clin Psychiatry 2017; 78: e1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Honer WG, Thornton AE, Chen EY, et al. Clozapine alone versus clozapine and risperidone with refractory schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2016; 354: 472–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stip E, Abdel-Baki A, Bloom D, et al. Les antipsychotiques injectables à action prolongée: Avis d’experts de l’Association des médecins psychiatres du Québec. Can J Psychiatry 2011; 56: 367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Verdoux H, Pambrun E, Tournier M, et al. Risk of discontinuation of antipsychotic long-acting injections vs. oral antipsychotics in real-life prescribing practice: a community-based study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017; 135: 429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]