Abstract

Planococcus maritimus Y42, isolated from the petroleum-contaminated soil of the Qaidam Basin, can use crude oil as its sole source of carbon and energy at 20 °C. The genome of P. maritimus strain Y42 has been sequenced to provide information on its properties. Genomic analysis shows that the genome of strain Y42 contains one circular DNA chromosome with a size of 3,718,896 bp and a GC content of 48.8%, and three plasmids (329,482; 89,073; and 12,282 bp). Although the strain Y42 did not show a remarkably higher ability in degrading crude oil than other oil-degrading bacteria, the existence of strain Y42 played a significant role to reducing the overall environmental impact as an indigenous oil-degrading bacterium. In addition, genome annotation revealed that strain Y42 has many genes responsible for hydrocarbon degradation. Structural features of the genomes might provide a competitive edge for P. maritimus strain Y42 to survive in oil-polluted environments and be worthy of further study in oil degradation for the recovery of crude oil-polluted environments.

Keywords: Planococcus maritimus, Qaidam Basin, Crude oil, Degradation, Genome

Introduction

Oil spills occur frequently and pose a severe hazard to pristine ecological conditions [1, 2]. On account of the difficulty in degrading crude oil, the pollutant remains in the environment to contaminate ground water and air, affect crop growth and endanger human health [3, 4]. Bioremediation is currently recognized as the preferred strategy to utilize biological activities to rapidly eliminate hydrocarbon pollutants [5]. Many microorganisms, especially bacteria, have been found to participate in the process of biodegradation in contaminated environments [6, 7].

Planococcus, as a psychrotolerant and halotolerant bacterium, was also reported as having the ability to degrade crude oil [8–10]. For example, a cultured Planococcus sp. strain S5 was described to be able to grow on salicylate or benzoate [11], and Planococcus alkanoclasticus was capable of degrading linear alkanes [9]. Meanwhile, most of the Planococcus bacteria have showed the ability to withstand heavy metals, produce surfactants and adapt to cold and/or saline environments [12–14]. Because of the above properties, Planococcus exhibited a potential capability in the bioremediation of extremely contaminated environments. Although many studies have reported the genomic backgrounds of Planococcus strains, oil biodegradation mechanisms in Planococcus have rarely been discussed. In the present study, we isolated a Planococcus strain from the oil-contaminated soils in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Our aims were to characterize the genome of this oil-degrading strain and to further seek responsible strategies associated with oil degradation in low-temperature environments.

Organism information

Classification and features

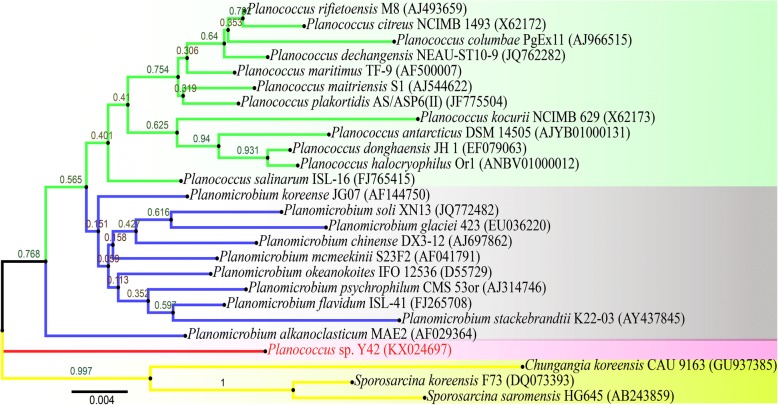

In this experiment, a novel cold-adapted strain Y42 was isolated from oil-contaminated soils in the Lenghu oil field, which is located in the northern margin of the Qaidam Basin (93.34°E, 38.71°N). The molecular identification of the strain was performed using the primers 27F and 1492R to amplify and sequence the 16S rRNA gene [15]. Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity showed that strain Y42 was closely related to members of the genus Planococcus (Planococcus maritimus (97%)). The strain Y42 was thus recognized as a potential new member of Planococcus (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of P. maritimus Y42 between known species of Planococcus genus. The phylogenetic tree constructed from the 16S rRNA sequence together with other Planococcus homologs using MEGA 6.0 software suite. The evolutionary history was inferred by using Neighbor-joining method based on model

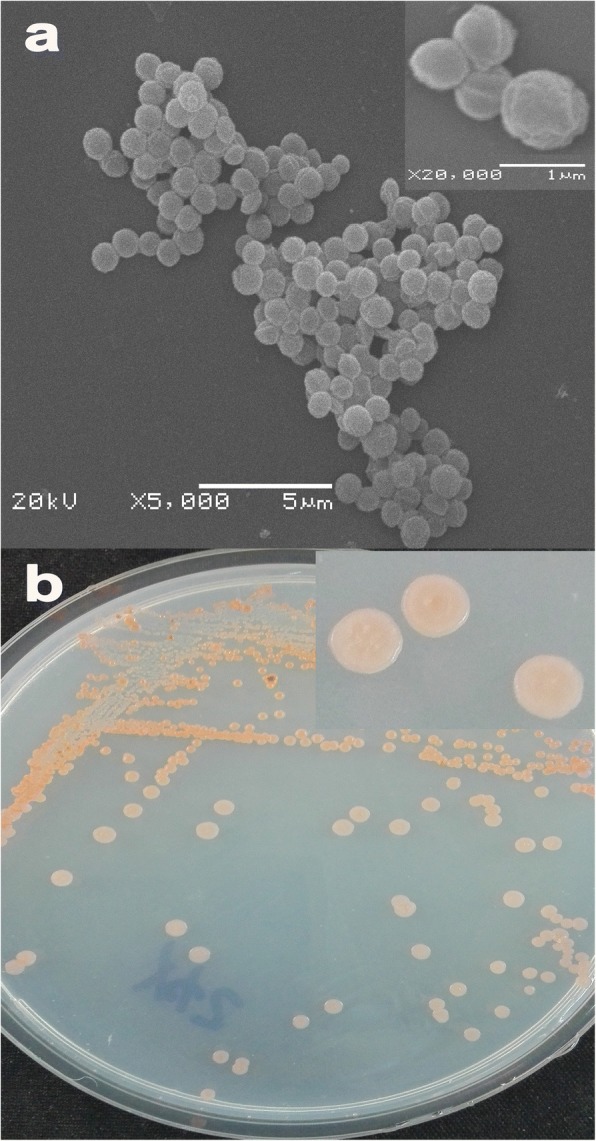

The strain Y42 was able to grow at moderately low temperatures, and many members of the genus Planococcus had been predominantly isolated from frozen and/or saline environments [16]. Cell micrographs were obtained by using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) on cells grown in LB medium. Cells of strain Y42 were coccoid, typically 0.7–1 m in diameter, and diplococci were observed, along with cell division septa (Fig. 2a). Colony morphology was determined on LB plates following 3–5 days of growth at 25 °C, which resulted in the formation of orange, round, umbonate colonies (Fig. 2b). Additional characteristics of P. maritimus Y42 are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Scanning electron microscope (a) and Colony morphology on the 216 L plate (b) of P. maritimus Y42

Table 1.

Classification and general features of P. maritimus Y42

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [42] | |

| Phylum Firmicutes | TAS [43] | ||

| Class Bacilli | TAS [44, 45] | ||

| Order Bacillales | TAS [46, 47] | ||

| Family Planococcaceae | TAS [46, 48] | ||

| Genus Planococcus | TAS [46, 49] | ||

| Species Planococcus | |||

| Strain Y42 | |||

| Gram stain | Positive | TAS [50] | |

| Cell shape | Coccoid | IDA | |

| Motility | Motile | TAS [50] | |

| Sporulation | Non-sporulating | TAS [50] | |

| Temperature range | 4–30 °C | IDA | |

| Optimum temperature | 25 °C | IDA | |

| pH range; Optimum | 6–9; 7.5; | IDA | |

| Carbon source | Yeast extract | IDA | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Frozen soil | IDA |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | < 15% NaCl (w/v) | TAS [50] |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | NAS |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living | IDA |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Non-pathogen | NAS |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | China: Qaidam Basin, Lenghu area | IDA |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection | 2015 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | + 38.71 (38°43′10.11″) | NAS |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | + 93.34 (93°20′30.1″) | NAS |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | 2789 m | NAS |

aEvidence codes – IDA Inferred from Direct Assay, TAS Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature), NAS Non-traceable. Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project

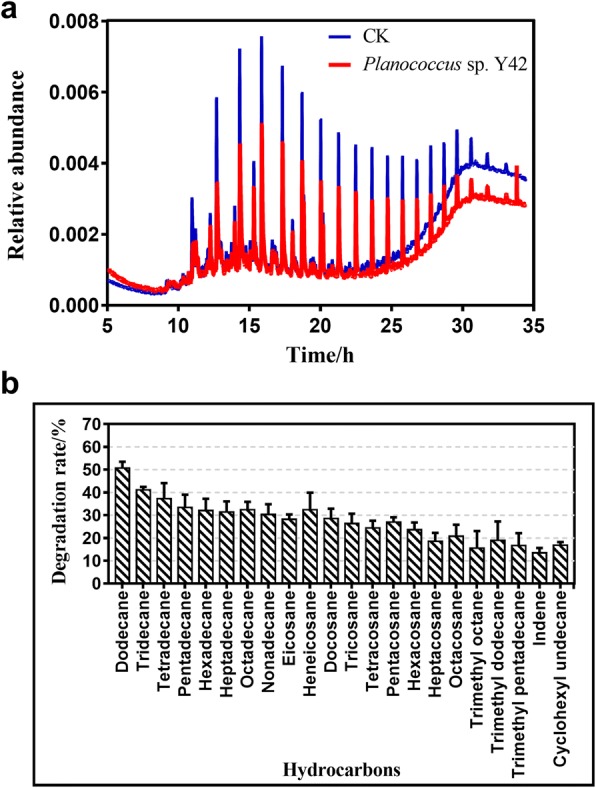

Crude oil-degrading characterization of strain Y42 was completed under specified growth conditions with crude oil as the sole carbon source by using a gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) method. The strain Y42 was cultured with MM medium (3.5 g of MgCl2, 1.0 g of NH4NO3, 0.35 g of KCl, 0.05 g of CaCl2, 1.0 g of KH2PO4, 1.0 g of K2HPO4, 0.01 g of FeCl3, 0.08 g of KBr, and 24 mg of SrCl2·6H2O, pH 7.5) with crude oil as a carbon source and incubated at 20 °C for 10 d [17]. A parallel experiment without inoculation was used as the control. The remaining oil from the cultures was extracted with 15 mL of hexane in a separating funnel at room temperature, and anhydrous Na2SO4 was then added to remove residual water. Ultimately, the extracted oil was analysed using a GC-MS method [18]. For GC-MS analysis, one microliter of the filtered solution was injected into a quartz capillary column (DB-WAX, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The total area of a detected individual hydrocarbon peak was defined as its hydrocarbon concentration in crude oil. The degradation rate of the components of crude oil was determined according to the following equation: η = (1-n1/n2) × 100%, where η, n1 and n2 are the degradation rate of the components of crude oil, the peak area of the components of crude oil remaining in the samples, and the peak area of the components of crude oil in the controls, respectively [19]. The chromatograms revealed that the concentrations of the components of crude oil, including n-alkanes, branched alkanes, cyclanes, and aromatic hydrocarbons, were lower in the sample treated with the strain P. maritimus Y42 than the abiotic control sample (Fig. 3a). After incubation for 10 days at 20 °C, the preferred degradation occurred in short-chain n-alkanes ranging from C12 to C18, C12 was particular decomposed, by approximately 50%. Meanwhile, the other straight-chain alkanes and aromatic hydrocarbons were decomposed by 20–30% (Fig. 3b). The strain Y42 did not show a remarkably higher ability to degrade different components of crude oil than other strains such as Bacillus [20, 21], Pseudomonas [22, 23], Rhodococcus [24] and etceteras. Even so, as an indigenous oil-degrading bacterium, the existence of the P. maritimus strain Y42 played a significant role in reducing overall environmental impact of the oil [25] and greatly enriched microbial community structures in the oil-contaminated soils in low-temperature environments [26].

Fig. 3.

The gas chromatograms of crude oil after degradation by P. maritimus Y42. a Total ion currents (TIC) of gas chromatography-mass spectrometer (GC-MS) monitoring the component variations of the residual crude oil (evaporated residue) before (the blue) and after (the red) incubation with strain Y42. b Degradation rates of the hydrocarbon components in evaporated crude oil by strain Y42 after 10 days of incubation at 20 °C

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing based on its phylogenetic position and its ability to degrade crude oil. The genome project was deposited in the genome online database [27] and the complete genome sequence was available in GenBank (NCBI-Genome). Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information was provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Project information of the whole genome sequence of P. maritimus Y42

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Paired-end and PacBio |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Illumina Hiseq 2000 and PacBio |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | PacBio: 300× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | SPAdes v. 3.5.0, HGAP |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Glimmer 3.02 |

| Locus Tag | B0X71 | |

| GenBank ID | CP019640.1-CP019643.1 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | April 14, 2017 | |

| GOLD ID | Gp0209326 | |

| BIOPROJECT | PRJNA371518 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source Material Identifier | Y42 |

| Project relevance | Biodegrading |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

P. maritimus strain Y42 was inoculated into LB liquid medium and grown on a gyratory shaker (200 rpm) at 20 °C for 96 h. Genomic DNA of the strain was extracted using the Bacterial Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (AxyPrep) as per its operation instruction.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The complete genome sequence of P. maritimus strain Y42 was generated by combined Illumina MiSeq with PacBio platform [28]. The reads generated with Illumina MiSeq platform were denovo assembled using Newbler (version 2.8). The sub-reads generated from PacBio platform were de novo assembled using Hierarchical Genome Assembly Process (HGAP) [29]. Gaps between contigs were closed by using the SPAdes-3.5.0. This whole genome project (Bioproject ID: PRJNA371518) has been registered and assembled sequence data submitted at NCBI GenBank under the accession no. CP019640.1-CP019643.1. And this finished genome was deposited in IMG database with the Project ID: Gp0209326.

Genome annotation

The completed genomic sequence was predicted using the Glimmer software 3.0 [30]. tRNA genes were predicted using tRNAscan-SE 1.3.1 [31] and rRNA genes were identified using Barrnap 0.4.2 [32]. The rest of the non-coding rRNA genes were predicted by using BLASTp against databases NCBI-NR database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and genes function annotations were assigned by the COG database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/).

Genome properties

The assembled genome of P. maritimus Y42 consisted of one circular DNA chromosome with a size of 3,718,896 bp and a GC content of 48.8% and three plasmids (329,482; 89,073; and 12,282 bp) (Table 3). Genome project information and genomic features are summarized in Table 4. From a total of 4155 genes, 3947 were annotated as predicted protein-coding sequences (CDS). In addition, the genome included 70 tRNA genes, 27 rRNA genes, 4 ncRNA genes, and 108 pseudogenes. Open reading frames (ORFs) were assigned into 23 functional categories under the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) and are represented in a circular genome map in Fig. 4. The COG distribution of genes is shown in Table 5. The genome map was visualized by the CG View server.

Table 3.

Summary of genome: 1 chromosome and 3 plasmids

| Label | Size (Mb) | GC% | INSDC identifier | RefSeq ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | 3.72 | 48.8 | CP019640.1 | NZ_CP019640.1 |

| Plasmid 1 | 0.329482 | 44.8 | CP019641.1 | NZ_CP019641.1 |

| Plasmid 2 | 0.089073 | 43.6 | CP019642.1 | NZ_CP019642.1 |

| Plasmid 3 | 0.012282 | 45 | CP019643.1 | NZ_CP019643.1 |

Table 4.

Genome statistics of P. maritimus Y42

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,149,733 | 100 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 3,541,381 | 85.34 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 2,005,184 | 48.32 |

| DNA scaffolds | 4 | 100 |

| Total genes | 4283 | 100 |

| Protein coding genes | 4172 | 97.41 |

| RNA genes | 111 | 2.59 |

| Pseudo genes | 108 | |

| Genes in internal clusters | NA | |

| Genes with function prediction | 3162 | 73.83 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2696 | 62.95 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 3323 | 77.59 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 186 | 4.34 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 959 | 22.39 |

| CRISPR repeats | NA |

Fig. 4.

The genome map of P. maritimus strain Y42. The circles show the different descriptions of the content in megabases, from the outside to inward: outer two circles represent the predicted protein-coding sequences and CDS regions on the plus and minus strands, respectively. The colors represent COG functional classification. The circle 3 represent the predicted rRNA and tRNA. The 4th circle shows GC content and 5th circle exhibits the percent of GC-skew

Table 5.

Number of genes of P. maritimus Y42 with the general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | % of totala | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 225 | 7.34 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 185 | 6.04 | Transcription |

| L | 117 | 3.82 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.03 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 36 | 1.17 | Cell cycle control, Cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| V | 71 | 2.32 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 144 | 4.7 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 134 | 4.37 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 47 | 1.53 | Cell motility |

| U | 33 | 1.08 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 118 | 3.85 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 183 | 5.97 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 172 | 5.61 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 297 | 9.69 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 95 | 3.1 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 161 | 5.25 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 172 | 5.61 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 187 | 6.1 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 95 | 3.1 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 325 | 10.6 | General function prediction only |

| S | 180 | 5.87 | Function unknown |

| – | 1587 | 37.05 | Not in COGs |

aThe total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the genome

Insights from the genome sequence

Genome annotation predicted that many genes support the adaptability of strain Y42 to cold and crude oil-contaminated environments. Based on the COG analysis, the genes related to general function prediction only (R) and amino acid transport and metabolism (E) were relatively enriched over the other functional genes. The results indicate genome-wide selection pressure [33]. Moreover, the abundance of genes related to functions unknown (S) in strain Y42 suggested that the strain may possess many new genes.

Further analysis showed that many key oxygenase genes were located in the P. maritimus Y42 genome, including those of catechol 1,2-dioxygenase (catA), catechol 2,3-dioxygenase (catE), and cytochromes P450. In addition, dehalogenase-coding genes were also found in the chromosome; these genes were involved in numerous metabolic processes such as the degradation of chlorocyclohexane, chlorobenzene, chloroalkane and chloroalkene [34]. A total of 9 genes putatively encoding for crude oil metabolites were identified in this genome (Fig. 5). The existence of these oxygenase genes could regioselectively oxidize substrates, especially natural aromatic compounds, by transferring oxygen to the substrates and transforming non-reactive hydrocarbons into available hydrocarbons [35, 36]. However, genes responsible for n-alkane degradation, such as the alkB gene, which is considered as functional biomarker gene for alkane degradation [37–39], were not found in the genome of strain Y42. These results imply that the strain Y42 might have some novel genes that participate in the catabolism of n-alkane pollutants.

Fig. 5.

Gene clusters in the genome of P. maritimus strain Y42 encoding metabolic functions for oil degradation. The corresponding oil degradation related genes are red colored

In addition, three cold shock proteins (WP_008296927.1, WP_026692369.1, WP_008298364.1.) were predicted, and these proteins were supposed to play important roles under low-temperature conditions [40]. In total, 238 genes were predicted to be involved in transport systems for aromatic compounds, amino acids, carbohydrates, lipids and inorganic ions. Among these genes, several osmoprotectant transport system (Opu) genes were identified to likely maintain the homeostasis of strain Y42. Furthermore, a large number of divalent cation transport and sulfate/phosphonate/nitrogen uptake systems guarantee the supply of nutrient elements for microbes in crude oil environments [41]. These genes were essential for strain Y42 to gain a competitive edge in oil-polluted soils.

Conclusions

The strain Y42, as a potential new member of Planococcus, was isolated from a cold and crude oil-contaminated environment. A genomic analysis of strain Y42 provided the theoretical basis for the mechanism of oil degradation by bacteria. Genes involved in cold shock and transport systems point to the potential capacity of strain Y42 for soil bioremediation contaminated by aromatic compounds in cold environments. Genomic research on strain Y42 would also provide a blueprint for the application of bioremediation and recovery in cold oil-polluted environments.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was financed by the International Scientific and Technological Cooperation Projects of the Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant No. 2014DFA30330) and the National Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31470544).

Abbreviation

- CDSs

protein-coding sequences

- COG

Clusters of Orthologous Groups categories

- GC-MS

gas chromatography and mass spectrometric Detector

- ORFs

open reading frames

Authors’ contributions

RQY, WZ and GSZ initiated the study. GSZ, TC and GXL designed the research and project outline. RQY drafted the manuscript. RQY and SJC isolated the strain. RQY assembled and annotated the genome. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guangxiu Liu, Phone: +86-0931-4967624, Email: liugx@lzb.ac.cn.

Tuo Chen, Phone: +86-0931-4967525, Email: chentuo@lzb.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Bao M, Wang L, Sun P, Cao L, Zou J, Li Y. Biodegradation of crude oil using an efficient microbial consortium in a simulated marine environment. Mar Pollut Bull. 2012;64:1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Head IM, Jones DM, Röling WFM. Marine microorganisms make a meal of oil. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang XX, Cheng SP, Zhu CJ, Sun SL. Microbial PAH-degradation in soil: degradation pathways and contributing factors. Pedosphere. 2006;16:555–565. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(06)60088-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Udo EJ, Fayemi AAA. The effect of oil pollution of soil on germination, growth and nutrient uptake of corn. J Environ Qual. 1975;4(4):537–540. doi: 10.2134/jeq1975.00472425000400040023x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassanshahian M, Emtiazi G, Cappello S. Isolation and characterization of crude-oil-degrading bacteria from the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea. Mar Pollut Bull. 2012;64:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AL-Saleh E, Drobiova H, Obuekwe C. Predominant culturable crude oil-degrading bacteria in the coast of Kuwait. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2009;63:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2008.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimes NE, Callaghan AV, Suflita JM, Morris PJ. Microbial transformation of the Deepwater horizon oil spill-past, present, and future perspectives. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:603. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chand R, Liaqat S, Bashir S, Naseer M, Ishrat N. Characterization of crude oil contaminated soil bacteria and laboratory-scale biodegradation experiments. Biologia. 2011;57:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelhardt MA, Daly K, Swannell RP, Head IM. Isolation and characterization of a novel hydrocarbon-degrading, gram positive bacterium, isolated from intertidal beach sediment, and description of Planococcus alkanoclasticus sp. nov. J Appl Microbiol. 2001;90:237–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun JQ, Xu L, Zhang Z, Li Y, Tang YQ, Wu XL. Diverse bacteria isolated from microtherm oil-production water. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;105:401–411. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-0088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Łabużek S, Hupert-Kocurek K, Skurnik M. Isolation and characterisation of new Planococcus sp. strain able for aromatic hydrocarbons degradation. Acta Microbiol Pol. 2003;52:395–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Liu YH, Luo N, Zhang XY, Luan TG, Hu JM, et al. Biodegradation of benzene and its derivatives by a psychrotolerant and moderately haloalkaliphilic Planococcus sp. strain ZD22. Res Microbiol. 2006;157:629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nithya C, Gnanalakshmi B, Pandian SK. Assessment and characterization of heavy metal resistance in Palk Bay sediment bacteria. Mar Environ Res. 2011;71:283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobucci DFC, Oriani MRG, Regina L. Reducing COD level on oily effluent by utilizing biosurfactant-producing bacteria. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2009;52:1037–1042. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132009000400029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seemüller E, Schneider B, Mäurer R, Ahrens U, Daire X, Kison H, et al. Phylogenetic classification of phytopathogenic mollicutes by sequence analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44(3):440–446. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-3-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mykytczuk NCS, Wilhelm RC, Whyte LG. Planococcus halocryophilus sp. nov., an extreme sub-zero species from high Arctic permafrost. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:1937–1944. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.035782-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang B, Lai Q, Cui Z, Tan T, Shao Z. A pyrene-degrading consortium from deep-sea sediment of the West Pacific and its key member Cycloclasticus sp. P1. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:1948–1963. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassanshahian M, Zeynalipour MS, Musa FH. Isolation and characterization of crude oil degrading bacteria from the Persian Gulf (Khorramshahr provenance) Mar Pollut Bull. 2014;82:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng MC, Li J, Liang FR, Yi M, Xu XM, Yuan JP, et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel hydrocarbon- degrading bacterium Achromobacter sp. HZ01 from the crude oil-contaminated seawater at the Daya bay, southern China. Mar Pollut Bull. 2014;83:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parthipan P, Preetham E, Machuca LL, Rahman PK, Murugan K, Rajasekar A. Biosurfactant and degradative enzymes mediated crude oil degradation by bacterium Bacillus subtilis A1. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:193. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bezza FA, Chirwa EMN. Production and applications of lipopeptide biosurfactant for bioremediation and oil recovery by Bacillus subtilis CN2. Biochem Eng J. 2015;101:168–178. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2015.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pacwa-Płociniczak M, Płaza GA, Poliwoda A, Piotrowska-Seget Z. Characterization of hydrocarbon-degrading and biosurfactant-producing Pseudomonas sp. P-1 strain as a potential tool for bioremediation of petroleum-contaminated soil. Environ Sci Pollut R. 2014;21(15):9385–9395. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2872-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patowary K, Patowary R, Kalita MC, Deka S. Characterization of biosurfactant produced during degradation of hydrocarbons using crude oil as sole source of carbon. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:279. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C, Zhou ZX, Jia XQ, Chen Y, Liu J, Wen JP. Biodegradation of crude oil by a newly isolated strain Rhodococcus sp. JZX-01. Appl Biochem Biotech. 2013;171(7):1715–1725. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atlas RM, Hazen TC. Oil biodegradation and bioremediation: a tale of the two worst spills in US history. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(16):6709–6715. doi: 10.1021/es2013227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee J, Han I, Kang BR, Kim SH, Sul WJ, Lee TK. Degradation of crude oil in a contaminated tidal flat area and the resilience of bacterial community. Mar Pollut Bull. 2017;114(1):296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liolios K, Chen IMA, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, et al. The genomes on line database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;38(suppl 1):D346–D354. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quail MA, Smith M, Coupland P, Otto TD, Harris SR, Connor TR, et al. A tale of three next generation sequencing platforms: comparison of ion torrent, Pacific biosciences and Illumina MiSeq sequencers. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chin CS, Alexander DH, Marks P, Klammer AA, Drake J Heiner C, et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Meth. 2013;10:563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:673–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chain PSG, Denef VJ, Konstantinidis KT, Vergez LM, Agullo L, Reyes VL, et al. Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 harbors a multi-replicon, 9.73-Mbp genome shaped for versatility. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:15280–15287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606924103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harayama S, Kok M, Neidle EL. Functional and evolutionary relationships among diverse oxygenases. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:565–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Beilen JB, Funhoff EG. Expanding the alkane oxygenase toolbox: new enzymes and applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emanuele K, Sebben BG, Helena PV. New alk genes detected in Antarctic marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:669–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallisch S, Gril T, Dong X, Welzl G, Bruns C, Heath E, et al. Effects of different compost amendments on the abundance and composition of alkB harboring bacterial communities in a soil under industrial use contaminated with hydrocarbons. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:96. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang W, Wang L, Shao Z. Diversity and abundance of oil-degrading bacteria and alkane hydroxylase (alkB) genes in the subtropical seawater of Xiamen Island. Microb Ecol. 2010;60:429–439. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9724-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chattopadhyay MK. Mechanism of bacterial adaptation to low temperature. J Biosci. 2006;31:157–165. doi: 10.1007/BF02705244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamamura N, Olson SH, Ward DM, Inskeep WP. Microbial population dynamics associated with crude-oil biodegradation in diverse soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:6316–6324. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01015-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibbons NE, Murray RGE. Proposals concerning the higher taxa of bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1978;28:1–6. doi: 10.1099/00207713-28-1-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Euzéby J. Validation list no. 132. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:469–472. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.022855-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ludwig W, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB, Class I. Bacilli class nov. In: De Vos P, Garrity G, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB, editors. Bergey’s man Syst Bacteriol, second edition. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2009. pp. 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1980;30:225–420. doi: 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prévot AR. In: Dictionnaire des Bactéries Pathogènes. 2. Pathogènes D d B, Hauderoy P, Ehringer G, Guillot G, Magrou J, Prévot AR, Rosset D, Urbain A., editors. Paris: Masson et Cie; 1953. pp. 1–692. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krasil’nikov NA. Guide to the Bacteria and Actinomycetes [Opredelitelv Bakterii i Actinomicetov] Moscow: Akad. Nauk SSSR; 1949. p. 328. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Migula W. Über ein neues System der Bakterien. Arbeiten aus dem bakteriologischen Institut der technischen Hochschule zu Karlsruhe 1894;1:235–238.

- 50.Ludwig W, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB. Family VI. Planococcaceae Krasil’nikov 1949, 328AL. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, volume 3, The Firmicutes 2011;3:348–350.