Abstract

Background

Physical activity (PA) and diet are 2 lifestyle factors that affect cardiometabolic risk. However, data on how a high-fat high-carbohydrate (HFHC) diet influences the effect of different intensities of PA on cardiometabolic health and cardiovascular function in a controlled setting are yet to be fully established. This study investigated the effect of sedentary behavior, light-intensity training (LIT), and high-intensity interval training (HIIT) on cardiometabolic markers and vascular and cardiac function in HFHC-fed adult rats.

Methods

Twelve-week-old Wistar rats were randomly allocated to 4 groups (12 rats/group): control (CTL), sedentary (SED), LIT, and HIIT. Biometric indices, glucose and lipid control, inflammatory and oxidative stress markers, vascular reactivity, and cardiac electrophysiology of the experimental groups were examined after 12 weeks of HFHC-diet feeding and PA interventions.

Results

The SED group had slower cardiac conduction (p = 0.0426) and greater thoracic aortic contractile responses (p < 0.05) compared with the CTL group. The LIT group showed improved cardiac conduction compared with the SED group (p = 0.0003), and the HIIT group showed decreased mesenteric artery contractile responses compared with all other groups and improved endothelium-dependent mesenteric artery relaxation compared with the LIT group (both p < 0.05). The LIT and HIIT groups had lower visceral (p = 0.0057 for LIT, p = 0.0120 for HIIT) and epididymal fat (p < 0.0001 for LIT, p = 0.0002 for HIIT) compared with the CTL group.

Conclusion

LIT induced positive adaptations on fat accumulation and cardiac conduction, and HIIT induced a positive effect on fat accumulation, mesenteric artery contraction, and endothelium-dependent relaxation. No other differences were observed between groups. These findings suggest that few positive health effects can be achieved through LIT and HIIT when consuming a chronic and sustained HFHC diet.

Keywords: High-intensity interval training, Inflammation, Light-intensity training, Metabolic syndrome, Oxidative stress, Sedentary behavior, Western diet

1. Introduction

Globally, an increasing proportion of people are consuming a diet characterized by a high intake of fat and sugar, also known as the Western diet.1 Diets such as these increase the risk of developing the cardiometabolic syndrome1, 2, 3 by inducing sustained increases in triglycerides, very low-density lipoprotein, and plasma glucose.4 Cardiometabolic syndrome is the clustering of the following risk factors: central obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, microalbuminuria, and hypercoagulability.5, 6 Collectively, these risk factors also increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease and diabetes.5

The key risk factors for the development of cardiometabolic syndrome are low physical activity (PA) and a poor-quality diet predominantly high in saturated fat, protein, and simple sugars.7, 8, 9 The intensity of PA occurs on a continuum from sedentary to light, moderate, and vigorous. Substantial research has documented the positive effects of moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) on traditional cardiometabolic risk factors such as obesity, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension.10, 11 Recently, owing to evidence implicating inflammation and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of cardiometabolic disease,12 several studies have evaluated the effects of MVPA on novel risk factors and found decreases in plasma biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction (P-selectin) and inflammation (tumor necrosis factor α) following MVPA.13, 14, 15, 16

Currently, there is growing interest in how time spent in activities at the lower end of the PA intensity continuum affect health relative to MVPA, because a greater proportion of the waking day is spent in these activities.17 There is mixed evidence regarding the impact of sedentary behavior18 and light-intensity activity19 on some cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors (i.e., obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia). However, despite the knowledge that greater total activity is better for health, there has been a trend toward overall declines in total activity20, 21 and increased sedentary behavior.17, 22 To this end, efforts to optimize health by increasing PA have led to numerous studies focused on identifying alternative approaches to MVPA.23, 24 Light-intensity training (LIT)25, 26 and high-intensity interval training (HIIT)23 have been suggested as an alternate means of promoting PA to improve health. LIT refers to PA prescriptions that call for an expenditure of less than 40% of maximal oxygen uptake; it has been suggested that this is a more attainable target compared with continuous MVPA.10 In contrast, HIIT involves alternating short bursts of high-intensity exercise with less-intense recovery periods requiring less time to perform than continuous MVPA.23 Recent published data have demonstrated that both LIT26, 27, 28, 29 and HIIT30, 31, 32 induce positive adaptations that may reduce cardiometabolic risks. Specifically, LIT was found to improve blood pressure in physically inactive populations with a medical condition,19 whereas HIIT was found to improve glucose control33 in healthy individuals and to improve insulin sensitivity and lipoproteins34 in individuals with metabolic syndrome. In rats fed standard chow, LIT and HIIT were found to improve body weight, fat accumulation, glucose control, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and total cholesterol (TC) levels, and mesenteric vessel contractile response.35

Several studies have examined the impact of low-calorie low-fat diet and PA on health and found a significant reduction in the risk of developing CVD and diabetes compared with a placebo or an educational support group.36, 37, 38, 39 However, although healthy diet and increased PA improve health,40 many people in developed countries and increasingly in developing countries are becoming sedentary and are consuming significant elements of the Western diet.41, 42 Thus, it is valuable to understand how sedentary behavior and alternative activity modes such as LIT and HIIT affect cardiometabolic risk in populations consuming the Western diet. Therefore, this study aims to determine the effects of sedentary behavior, LIT, and HIIT on metabolic markers and cardiac and vascular function in male adult rats fed with a high-fat high-carbohydrate (HFHC) diet.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and animals

All research procedures were granted prior approval by Central Queensland University (CQU) Animal Ethics Research Committee (A13/08-303) in accordance with the guidelines of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Male Wistar rats (n = 48) were bred and housed at CQU in an environmentally controlled room (temperature 22°C ± 1°C, relative humidity 50% ± 2%) with a 12 h light–dark cycle. Male rats were used to avoid variability caused by hormonal cycles in females as well as because of their more similar homeostatic adaptation (negative energy balance) to exercise in humans compared with female rats.43, 44 Water and standard rat chow (Riverina Stockfeeds, South Brisbane, Australia) were provided ad libitum for 12 weeks. After 12 weeks of aging, rats (437.8 ± 3.9 g) were randomly divided into 4 groups, each comprising 12 animals: control (CTL), sedentary (SED), LIT, and HIIT. Rats were subjected to 12 weeks of PA intervention and HFHC diet feeding in all groups. All rats at 24 weeks of age were euthanized at the end of the intervention period.

2.2. PA protocol

During the 12-week intervention period, animals were subjected to each of the following PA protocols. The CTL group was housed 3 or 4 rats per standard cage with 2400 cm2 floor area (400 cm2/400 g rat) and was not subjected to any exercise training beyond normal cage activity. The SED group was not subjected to any exercise training and was housed 3 rats per small cage with 1080 cm2 floor area (240 cm2/400 g rat) to initiate a significant reduction in PA.45 The LIT group was housed 3 or 4 rats per standard cage with 2400 cm2 floor area (400 cm2/400 g rat) and ran at a treadmill speed of 8 m/min, 0% incline, for 125 min/day divided into 4 bouts (30-30-30-35 min) separated by a 2 h rest period, 5 days/week for 12 weeks.46 The HIIT group was housed 3 or 4 rats per standard cage with 2400 cm2 floor area (400 cm2/400 g rat) and was trained starting at a treadmill speed of 10 m/min, 0% incline, for 10–15 min/day, progressively increased at a speed of 50 m/min, 10% incline, divided into four 2.5 min work bouts separated by a 3 min rest period, 5 days/week for 12 weeks (training protocol followed as described by Matsunaga et al.47).

2.3. Diet protocol

Rats received an HFHC diet (with 25% fructose solution incorporated in the drinking water)48 ad libitum during the 12-week intervention period. The composition of this diet is listed in Table 1. Wistar rats (which are more susceptible to obesity) fed with an HFHC diet generally develop metabolic syndrome, which shares many features with human metabolic syndrome.49 Twenty-four-hour food and water (fructose) intakes for all animal groups were monitored weekly throughout the intervention period. The average 24 h food and water intake per week was noted. Energy intake (kJ/g) was calculated for the food or water consumed.

Table 1.

Animal diet composition.

| Ingredients | Standard chow | HFHC diet |

|---|---|---|

| Powdered rat feed (g/kg) | 1000 | 155 |

| H.M.W. salt mixture (g/kg) | 25 | |

| Beef tallow (g/kg) | 200 | |

| Condensed milk (g/kg) | 395 | |

| Fructose (g/kg) | 175 | |

| Water (mL/kg) | 50 | |

| Energy (kJ/g) | 12.2 | 17.9 |

| Macronutrients (%) | ||

| Total carbohydrate | 42 | 52 |

| Total fat | 5 | 24 |

| Total protein | 25 | 6 |

| Total fiber | 6 | 1 |

Abbreviations: HFHC = high-fat high-carbohydrate; H.M.W. = Hubble Mendal and Wakeman.

2.4. Body weight, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and heart rate (HR)

Body weights, SBP, and HR were recorded every 4 weeks. Rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of Zoletil® (zolazepam/tiletamine, 15 mg/kg) prior to SBP readings. SBP and HR measurements were taken via tail-cuff plethysmography using an MLT1010 Pulse Transducer (ADInstruments, Bella Vista, Australia) and inflatable tail-cuff connected to an MLT844 Physiological Pressure Transducer (ADInstruments), and PowerLab data acquisition unit (ADInstruments).50

2.5. Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

OGTT was performed every 4 weeks after an overnight fast (10–12 h). Rats were administered 40% glucose (2 g/kg) via oral gavage. Tail-vein blood samples were taken at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min, and blood glucose concentrations were measured using a Medisense Precision QID glucose meter (Abbott Laboratories, Princeton, NJ, USA). Area under the curve was calculated using the blood glucose levels measured over the 2 h period.

2.6. Terminal assessments

At completion of the 12-week intervention period, all rats were euthanized after a 24 h rest period via intraperitoneal injection of Lethabarb® (sodium pentobarbitone, 1.5 mg/kg) prepared at a concentration of 375 mg/mL. Following euthanasia, the chest cavity was opened and heart, kidney, liver, spleen, and fats pads (visceral and epididymal) were removed and weighed (weight normalized to tibial length). Blood serum was collected and stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis. Electrophysiological studies and isolated thoracic aortic and mesenteric ring organ baths were then performed to assess changes in cardiovascular function.

2.7. Biochemical assays

Biochemical measurements were performed using blood collected from the abdominal vena cava of each rat. Blood samples were allowed to clot, then centrifuged for 10 min at 4000 rpm. Serum was aliquoted to microtubes and stored at −80°C until further analysis. The Sorte and Basak51 modified copper–cadmium reduction method was used to quantify total nitric oxide concentrations. Abcam assay kits (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) prepared according to manufacturer-provided standards and protocols were used to measure serum triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and HDL concentrations. TC was calculated using a modified Friedlander formula.52 Mercodia Rat Insulin ELISA kit (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden) was used to determine serum levels of insulin, and R&D Systems Rat IL-6 DuoSet ELISA (Catalogue Number DY506) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used to quantify interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentration. The Briskey et al.53 optimized gas chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry protocol was used to measure total F2-isoprostane levels.

2.8. Cardiac function

The left ventricular papillary muscle was pinned between 2 earth-isolated platinum electrodes in a 1.0 mL experimental chamber filled with Tyrode's physiological salt solution (37°C, aerated with 95%O2–5%CO2). The papillary muscle was slowly stretched to a maximum preload (5–10 m⋅N) and was then stimulated using the Grass SD9 stimulator (West Warwick, RI, USA) at a frequency of 1 Hz, pulse width of 0.5 ms, and stimulus strength of 20% above threshold. After a 5 min equilibration period, the papillary muscle was then impaled by glass microelectrodes filled with 3M potassium chloride ((World Precision Instruments; Sarasota, FL, USA) filamented borosilicate glass, outer diameter 1.5 mm, tip resistance of 5–15 mΩ) using a silver/silver chloride reference electrode. The electrical activity (mV) of a cell was recorded with a Cyto 721 electrometer (World Precision Instruments) connected to a PowerLab data recording system (ADInstruments).

2.9. Vascular function

Thoracic aortic rings isolated from each rat were suspended in individual 25 mL organ baths filled with Tyrode's buffer at 37°C aerated with 95%O2–5%CO2. Mesenteric arteries dissected from the intestine vasculature were threaded with 40 µm stainless steel wire while bathed in Tyrode's solution, then transferred to 10 mL myograph chambers containing Tyrode's buffer at 37°C aerated with 95%O2–5%CO2. Aortic and mesenteric rings were allowed to equilibrate for 30 min at a resting tension of ~10 m⋅N. After equilibration, mesenteric arteries were normalized using an automated normalization function,54 were contracted with 10 mmol/L potassium chloride, and were relaxed with 0.01 mmol/L acetylcholine. Cumulative concentration-contraction curves were measured for noradrenaline (Sigma-Aldrich, Castle Hill, Australia) on both aortic and mesenteric vessels. Cumulative concentration-relaxation curves were measured for acetylcholine (Sigma-Aldrich) and sodium nitroprusside (Sigma-Aldrich) following submaximal (70%) contraction to noradrenaline.50

2.10. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Food and water intake, body weight, SBP, HR, and vascular functional parameters were analyzed using separate two-way (group × time) analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc analysis for multiple comparisons. Cardiometabolic and one-way analyses of variance with Bonferroni post hoc comparisons. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Food, water, and energy intake

Table 2 presents the mean 24 h food, energy, and water intake of the experimental groups at Weeks 0, 4, 8, and 12 of intervention. There were no significant between-group differences in food, water, and energy intake throughout the intervention period. No group × time interaction was observed for food (p = 0.5435), water (p = 0.1555), and energy (p = 0.2034) intake. No main effect for group was observed for food (p = 0.1335), water (p = 0.0891), and energy (p = 0.1660) intake, but there was a significant main effect for time (all p < 0.0001). Follow-up analyses showed all groups had significantly lower food and water intake, and significantly higher energy intake at Weeks 4, 8, and 12 compared with Week 0 (all p < 0.0001). No significant difference in food, water, and energy intake in all groups was observed at Week 12 compared with Weeks 4 and 8.

Table 2.

Mean 24 h food and water intake of experimental groups at 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks of intervention (mean ± SEM).

| Measures | CTL (n = 12) | SED (n = 12) | LIT (n = 12) | HIIT (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food intake (g/24h) | ||||

| 0 week | 33.5 ± 5.0 | 37.6 ± 1.1 | 33.5 ± 0.8 | 37.5 ± 0.7 |

| 4 weeks | 15.9 ± 1.2* | 16.4 ± 0.4* | 14.6 ± 1.2* | 14.8 ± 0.4* |

| 8 weeks | 15.9 ± 1.4* | 16.8 ± 0.3* | 14.2 ± 1.5* | 14.1 ± 0.9* |

| 12 weeks | 16.1 ± 2.4* | 14.7 ± 0.5* | 14.2 ± 0.6* | 16.8 ± 0.8* |

| Water intake (mL/24h) | ||||

| 0 week | 92.1 ± 8.2 | 82.9 ± 2.7 | 71.3 ± 1.3 | 88.1 ± 7.3 |

| 4 weeks | 22.9 ± 1.5* | 29.6 ± 2.1* | 22.1 ± 1.0* | 24.9 ± 0.8* |

| 8 weeks | 21.6 ± 1.3* | 23.1 ± 4.6* | 25.8 ± 2.9* | 29.3 ± 3.4* |

| 12 weeks | 24.8 ± 2.5* | 21.4 ± 0.9* | 23.7 ± 1.1* | 28.5 ± 1.4* |

| Energy intake (kJ/g/day) | ||||

| 0 week | 408.6 ± 61.1 | 458.4 ± 13.4 | 408.2 ± 9.6 | 457.9 ± 8.2 |

| 4 weeks | 670.2 ± 43.2* | 782.8 ± 34.0* | 631.9 ± 36.1* | 683.7 ± 18.5* |

| 8 weeks | 646.8 ± 30.1* | 688.3 ± 78.7* | 736.0 ± 18.3* | 745.0 ± 55.5* |

| 12 weeks | 704.5 ± 77.6* | 622.6 ± 20.1* | 652.1 ± 24.6* | 779.5 ± 37.0* |

Abbreviations: CTL = control group; HIIT = high-intensity interval trained group; LIT = light-intensity trained group; SED = sedentary group.

p < 0.0001, compared with 0 week within group.

3.2. Body and organ weights

Table 3 presents the body weights of the experimental groups at Weeks 0, 4, 8, and 12 and organ weights of experimental groups after 12 weeks of the intervention. Initial body weights ranged from 420.7 ± 12.2 g to 449.2 ± 8.2 g. No significant main effects or interactions were observed for body weight throughout the intervention period. At Week 12, the LIT (p = 0.0057) and HIIT (p = 0.0120) groups' visceral fat weight was significantly lower compared with the CTL group. The LIT group's epididymal fat weight was significantly lower compared with the CTL (p < 0.0001) and SED (p = 0.0447) groups, and the HIIT group's epididymal fat weight was significantly lower compared with the CTL group (p = 0.0002). No significant between-group differences were observed in the left and right ventricle, kidney, spleen, and liver weights at Week 12 of the intervention.

Table 3.

Body weights at Weeks 0, 4, 8, and 12 and organ weights of experimental groups after 12 weeks of intervention (mean ± SEM).

| Measures | CTL (n = 12) | SED (n = 12) | LIT (n = 12) | HIIT (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | ||||

| 0 week | 420.7 ± 12.2 | 437.0 ± 12.9 | 431.2 ± 10.6 | 449.2 ± 8.2 |

| 4 weeks | 406.2 ± 14.6 | 409.4 ± 17.2 | 393.7 ± 6.8 | 435.0 ± 12.3 |

| 8 weeks | 428.6 ± 18.0 | 437.9 ± 16.5 | 396.2 ± 6.9 | 425.6 ± 11.6 |

| 12 weeks | 443.2 ± 19.3 | 423.3 ± 16.5 | 394.9 ± 6.9 | 411.0 ± 13.0 |

| Organ weight at Week 12 (mg/mm) | ||||

| Visceral fat (mg/mm) | 398.0 ± 44.1 | 339.5 ± 25.9 | 247.2 ± 20.7* | 247.0 ± 23.3* |

| Epididymal fat (mg/mm) | 272.8 ± 24.7 | 210.3 ± 13.2 | 150.2 ± 9.7*# | 152.3 ± 17.7* |

| Left ventricle (mg/mm) | 22.8 ± 1.3 | 23.0 ± 0.7 | 22.8 ± 0.7 | 22.9 ± 0.9 |

| Right ventricle (mg/mm) | 6.0 ± 0.4 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.2 |

| Kidney (mg/mm) | 72.8 ± 3.7 | 75.1 ± 2.2 | 68.7 ± 2.4 | 80.1 ± 2.6 |

| Spleen (mg/mm) | 20.6 ± 2.0 | 18.9 ± 0.8 | 17.6 ± 0.5 | 20.0 ± 1.0 |

| Liver (mg/mm) | 372.0 ± 21.3 | 373.4 ± 17.6 | 357.5 ± 10.8 | 387.6 ± 17.6 |

Abbreviations: CTL = control group; HIIT = high-intensity interval trained group; LIT = light-intensity trained group; SED = sedentary group.

p < 0.05, compared with CTL;

p < 0.05, compared with SED.

3.3. SBP and HR

Table 4 presents SBP and HR of the experimental groups at 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks of intervention. No significant main effects or interactions were observed for SBP or HR throughout the intervention period.

Table 4.

SBP and HR of experimental groups at 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks of intervention (mean ± SEM).

| CTL (n = 12) | SED (n = 12) | LIT (n = 12) | HIIT (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP (mmHg) | ||||

| 0 week | 127.2 ± 1.8 | 133.0 ± 4.5 | 129.8 ± 2.0 | 128.0 ± 2.5 |

| 4 weeks | 135.7 ± 4.1 | 136.6 ± 3.7 | 131.3 ± 2.7 | 137.4 ± 1.7 |

| 8 weeks | 135.6 ± 1.6 | 139.0 ± 2.0 | 130.8 ± 2.4 | 136.6 ± 3.0 |

| 12 weeks | 133.5 ± 4.0 | 139.8 ± 2.4 | 134.7 ± 6.9 | 134.7 ± 4.7 |

| HR (beats/min) | ||||

| 0 week | 498.4 ± 16.7 | 504.8 ± 18.0 | 500.6 ± 15.3 | 501.1 ± 12.8 |

| 4 weeks | 510.4 ± 6.3 | 507.2 ± 6.7 | 504.7 ± 7.0 | 513.4 ± 7.7 |

| 8 weeks | 513.6 ± 7.4 | 509.0 ± 14.5 | 499.4 ± 6.2 | 516.2 ± 9.0 |

| 12 weeks | 510.6 ± 5.9 | 511.4 ± 11.6 | 499.0 ± 13.0 | 516.4 ± 13.8 |

Abbreviations: CTL = control group; HIIT = high-intensity interval trained group; HR = heart rate; LIT = light-intensity trained group; SBP = systolic blood pressure; SED = sedentary group.

3.4. Cardiometabolic parameters

Table 5 presents the cardiometabolic parameter outcomes of the experimental groups after 12 weeks of the intervention. There were no significant between-group differences observed in OGTT area under the curve at Weeks 0, 4, 8, and 12 of the intervention. No significant between-group differences were observed in LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides, TC, insulin, nitric oxide, IL-6, or F2-isoprostane.

Table 5.

Cardiometabolic parameter outcomes of experimental groups after 12 weeks of intervention (mean ± SEM).

| Measures | CTL (n = 12) | SED (n = 12) | LIT (n = 12) | HIIT (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OGTT AUC (mmol/L) | ||||

| 0 week | 1041.4 ± 35.3 | 1032.0 ± 48.0 | 970.8 ± 10.0 | 1010.7 ± 40.0 |

| 4 weeks | 864.0 ± 33.0 | 958.5 ± 27.6 | 906.0 ± 19.0 | 915.7 ± 35.1 |

| 8 weeks | 947.9 ± 43.3 | 936.0 ± 39.0 | 903.0 ± 19.7 | 979.0 ± 52.6 |

| 12 weeks | 927.5 ± 23.6 | 954.0 ± 42.0 | 828.0 ± 23.1 | 860.9 ± 24.1 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 128.3 ± 13.7 | 152.5 ± 10.0 | 121.6 ± 12.2 | 134.9 ± 6.2 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 45.4 ± 6.5 | 46.7 ± 5.7 | 46.5 ± 8.9 | 43.5 ± 14.9 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 103.4 ± 7.8 | 96.0 ± 4.4 | 137.6 ± 19.2 | 147.1 ± 17.8 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 188.7 ± 15.1 | 218.5 ± 13.3 | 206.6 ± 20.6 | 207.9 ± 12.5 |

| Insulin (ug/L) | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.06 |

| Nitric oxide (uM) | 25.7 ± 3.4 | 24.5 ± 4.8 | 21.8 ± 4.9 | 24.1 ± 5.4 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 49.5 ± 1.9 | 49.7 ± 2.4 | 54.1 ± 1.6 | 51.1 ± 2.6 |

| F2-isoprostane (pg/mL) | 472.3 ± 161.3 | 502.5 ± 158.3 | 579.7 ± 3.1 | 438.7 ± 11.9 |

Abbreviations: AUC = area under the curve; CTL = control group; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HIIT = high-intensity interval trained group; IL-6 = interleukin-6; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LIT = light-intensity trained group; OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test; SED = sedentary group; TC = total cholesterol.

3.5. Cardiac function

Table 6 presents cardiac function of the experimental groups after 12 weeks of the intervention. The SED group's action potential amplitude (APA) was significantly lower compared with the CTL group (p = 0.0426), and the LIT group's APA was significantly higher compared with the SED group (p = 0.0003). No significant between-group differences were observed in action potential duration (APD) at 20%, 50%, or 90% of the repolarization, in resting membrane potential, or in force of contraction.

Table 6.

Cardiac electrophysiology outcomes of experimental groups after 12 weeks of intervention (mean ± SEM).

| Cardiac action potential parameters | CTL (n = 12) | SED (n = 12) | LIT (n = 12) | HIIT (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APD20 | 17.0 ± 1.1 | 14.5 ± 0.8 | 18.4 ± 1.6 | 15.0 ± 1.3 |

| APD50 | 30.1 ± 3.0 | 26.8 ± 2.1 | 31.7 ± 3.5 | 23.6 ± 2.9 |

| APD90 | 108.1 ± 15.0 | 101.3 ± 10.1 | 88.7 ± 10.5 | 89.5 ± 14.4 |

| RMP | −62.3 ± 1.5 | −66.4 ± 1.8 | −67.3 ± 1.8 | −65.6 ± 1.5 |

| APA | 56.1 ± 4.3 | 42.4 ± 2.6* | 64.1 ± 2.6# | 51.3 ± 4.3 |

| Fc | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.4 |

Abbreviations: APA = action potential amplitude; APD20 = action potential duration at 20%; APD50 = action potential duration at 50%; APD90 = action potential duration at 90%; CTL = control group; Fc = force of contraction; HIIT = high-intensity interval trained group; LIT = light-intensity trained group; RMP = resting membrane potential; SED = sedentary group.

p < 0.05, compared with CTL;

p < 0.05, compared with SED.

3.6. Vascular function

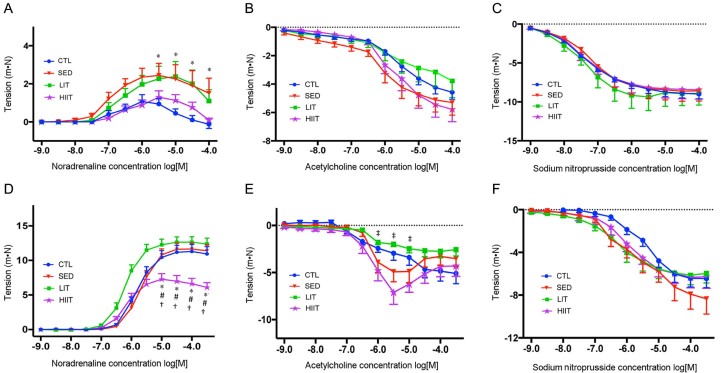

Fig. 1 presents vascular reactivity of the experimental groups at Week 12 of the intervention. The SED group demonstrated increased thoracic aortic contractile responses to noradrenaline compared with the CTL group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1A), whereas the HIIT group demonstrated decreased mesenteric artery contractile responses to noradrenaline compared with all other groups (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1D). Results regarding vasorelaxation of noradrenaline-precontracted vessels at Week 12 of the intervention demonstrated that HIIT improved endothelium-dependent mesenteric artery relaxation responses to acetylcholine compared with the LIT group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1E). No significant differences in endothelium-dependent aortic and endothelium-independent aortic and mesenteric relaxation were observed between groups after 12 weeks of the intervention.

Fig. 1.

Vascular functional changes in high-fat high-carbohydrate-fed rats after 12 weeks of intervention. (A) Noradrenaline-mediated contraction of the thoracic aorta; (B) Endothelium-dependent relaxation to acetylcholine of noradrenaline-precontracted thoracic aorta; (C) Endothelium-independent relaxation to sodium nitroprusside of noradrenaline-precontracted thoracic aorta; (D) Noradrenaline-mediated contraction of the mesenteric artery; (E) Endothelium-dependent relaxation to acetylcholine of noradrenaline-precontracted mesenteric artery; (F) Endothelium-independent relaxation to sodium nitroprusside of noradrenaline-precontracted mesenteric artery. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. Log[M] = negative logarithm to the base 10 of the molar concentration. * p < 0.05, compared with CTL; #p < 0.05, compared with SED; †p < 0.05, compared with LIT; ‡p < 0.05, compared with HIIT. CTL = control group; HIIT = high-intensity interval trained group; LIT = light-intensity trained group; SED = sedentary group.

4. Discussion

Studies have established that dietary factors and activity levels largely contribute to the development of the cardiometabolic syndrome.55, 56 The present study demonstrated that in rats fed with an HFHC diet, the SED group had lower APA and greater thoracic aortic contractile responses compared with the CTL group. The LIT group had a higher APA compared with the SED group, whereas the HIIT group showed a decreased mesenteric artery contractile response compared with all other groups and improved endothelium-dependent mesenteric artery relaxation compared with the LIT group. Additionally, the LIT and HIIT groups had decreased visceral and epididymal fat weights compared with the CTL group. These findings differ from those we recently reported showing that in animals fed standard chow and trained using the same LIT and HIIT protocols, LIT and HIIT groups demonstrated beneficial changes in body weight, fat accumulation, glucose control, HDL and TC levels, and mesenteric vessel contractile response to noradrenaline compared with the CTL group.35 Furthermore, the LIT group demonstrated significant improvements in insulin sensitivity and cardiac conduction, whereas the HIIT group demonstrated significant improvements in SBP and enhanced sensitivity to endothelium-independent relaxation in the aorta and mesenteric artery compared with the CTL group.35 These results suggest that limited beneficial effects are observed following LIT and HIIT prescriptions in rats consuming an HFHC diet.

Results of this study demonstrated significant decreases in food and water (fructose) intake in all groups at Weeks 4, 8, and 12 compared with Week 0 of intervention. This finding is in agreement57, 58, 59 with previous studies in rodents suggesting that the hypophagic effect of an HFHC diet is a way to maintain a stable body weight or fat. In contrast, other animal studies60, 61, 62 have shown increased food intake following an HFHC diet. Several factors are hypothesized to have contributed to this discrepancy. These include differences in experimental design, strain susceptibility to fructose manipulations, and palatability of the diet, which depends on the concentration and the ratio of fructose to fat.63 However, it should be noted that although several hypotheses63 have been proposed, it is still unclear what exactly influences an HFHC diet to stimulate or inhibit food intake in rats.

Although a significantly lower food and water intake was observed at Weeks 4, 8, and 12 compared with Week 0, energy intake was significantly higher in all groups at Weeks 4, 8, and 12 compared with Week 0. This finding was due to the higher energy content of the HFHC diet, leading to a higher energy intake. As observed in this study, rats given sugar solutions (fructose) in addition to solid food consumed more energy than rats given solid food alone, promoting changes in adipose deposition even without excessive weight gain.64 Thus, a sustained increase in intake was not essential to promote an increased energy intake in this model.

Several studies have demonstrated that MVPA can mitigate high-fat diet–induced weight gain.65, 66, 67 In the current study, no significant main effects or interactions were observed for body weight throughout the intervention period, suggesting that body weight was not altered in either sedentary, LIT, or HIIT rats fed with an HFHC diet. This is perhaps due to the hypophagic effect of an HFHC diet,57, 58, 59 which suppresses the effect of PA on body weights. Additionally, although feeding an HFHC diet has been linked to obesity and the metabolic syndrome in several animal models,68 data from this study failed to induce excessive weight gain in all groups, as evidenced by the nonsignificant difference in weight in all groups throughout the intervention period. Several rat studies have reported the failure of an HFHC diet to induce obesity,57, 69, 70, 71 and various reasons have been suggested to explain this occurrence. Investigators have suggested that following 6–8 weeks of HFHC feeding, increases in leptin (satiety hormone) production and central leptin sensitivity are observed in the animals, decreasing food intake and body weight.72 After 12 weeks, animals start to develop leptin resistance and obesity.72 Another suggestion is that Wistar rats are less responsive to weight gain following an HFHC diet compared with Sprague-Dawley rats owing to their higher basal metabolic rate.73, 74, 75 Lastly, it is hypothesized that induction of obesity is more effective when a high-fat diet is started at an early age (9 weeks of age) and administered for 8 weeks or more.76 These factors may have contributed to the failure of HFHC to induce obesity in this study.

It is established that body fat distribution is a better indicator of disease risk than body weight itself.77 In this study, although no changes in body weights were observed, the LIT and HIIT groups' visceral and epididymal fat weights were significantly lower compared with the CTL group. This finding suggests that LIT and HIIT can prevent fat accumulation (even without excessive weight gain), potentially decreasing cardiometabolic risk.78 Possible mechanisms underlying this LIT- and HIIT-induced fat prevention are an increase in the muscle enzymes that stimulate increased fat oxidation,79, 80 an increase in neurotransmitters contributing to post-training inhibition of food intake,81 and an increase in release of anorectic peptide (corticotropin-releasing factor) by the hypothalamus.82 Additionally, although not statistically significant, the SED group's visceral and epididymal fat weights were lower compared with the CTL group. In rodents, food intake is coupled with energy expenditure, such that decreased PA acutely reduces energy expenditure and food intake and consequently lowers fat accumulation.83

No significant main effects or interactions were observed for SBP or HR throughout the intervention period. The autonomic nervous system and its sympathetic arm play important roles in regulating blood pressure and HR.84, 85 Previous studies have confirmed that MVPA lessens sympathetic modulation of the heart,86, 87 whereas HFHC feeding enhances sympathetic activity.88 One study further demonstrated that MVPA attenuated high-fat diet-induced sympathetic activation.86 Results of this study showed that sedentary behavior, LIT, and HIIT had no effect on SBP and HR. Rats used were relatively young with normal vascular function, so it is possible that 12 weeks of restricted activity may not be enough to cause adverse cardiometabolic changes. The effect of LIT and HIIT on sympathetic activity has not been widely examined, and it is assumed that the HFHC feeding reduced the effect of LIT and HIIT on the sympathetic system; however, this remains to be clarified. Notably, blood pressure readings were showing an upward trend in the HFHC-fed groups, which may have become more apparent if the feeding trial had been extended beyond 12 weeks.

The role of PA and diet on glucose and lipid metabolism was also examined in the current study. No significant between-group differences were observed in OGTT area under the curve at 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks and no between-group differences in insulin, LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides, and TC at Week 12 of intervention. In rats fed with a standard diet, previous studies have demonstrated that LIT and HIIT89, 90 stimulate the rate of muscle glucose transport, reducing plasma glucose, whereas physical inactivity decreases the number of muscle glucose transporters, resulting in increased plasma glucose.91 Similarly, several animal studies using standard chow diets have shown that LIT and HIIT improve the lipid profile,31, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96 whereas physical inactivity reduces plasma triglyceride uptake into muscle and decreases HDL-C levels29 in rats fed with a standard diet. Results of this study showed that sedentary behavior, LIT, and HIIT had no effect on glucose and lipid metabolism in rats consuming an HFHC diet. The underlying mechanism is not fully understood, but it appears that the HFHC diet is hindering the effect of PA in glucose and lipid metabolism. This is an important finding in the context of this project, where the short duration of HFHC feeding (12 weeks) compared with other studies97, 98 did alter glucose responses to exercise training despite limited evidence of classic metabolic syndrome changes.

Recently, it has become apparent that the complex interaction of inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress are contributors to the pathogenesis of several diseases (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease).99, 100, 101 In this study, no significant between-group differences were observed in nitric oxide, IL-6, and F2-isoprostane concentrations following the various PA prescriptions. Similar animal studies have demonstrated different findings, where moderate-intensity exercise was found to reduce circulating inflammatory cytokines (IL-6)69 and oxidative stress markers (superoxide anion, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, and carbonyl)102 in rats fed with 8 weeks of a high-fat diet. However, these studies employed different training intensity and outcome measures69, 102 as well as rat models (adolescent rats).69 On the other hand, no significant differences in serum nitric oxide concentrations were observed between groups, which is in agreement with a previous study that demonstrated no change in the level of plasma nitric oxide after 4 weeks of moderate intensity exercise in Zucker obese rats.103 Results of this study showed that sedentary behavior, LIT, and HIIT had no effect on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers. However, because this is the first study to examine the influence of an HFHC diet with different intensities of PA on markers of inflammation and oxidative stress, more research is required to fully understand these results.

In this study, no significant between-group differences were observed for APD20, APD50, APD90, resting membrane potential, or force of contraction. After 12 weeks of intervention, the LIT group demonstrated a higher APA compared with the SED group despite the HFHC diet, whereas the SED group showed decreased APA compared with the CTL group. This finding suggests that LIT improved cardiac conduction, resulting in greater efficacy of cardiac impulse propagation.104, 105 In contrast, the SED group demonstrated slower cardiac conduction, potentially increasing CVD risk by impairing ventricular pressure development and increasing myocardial oxygen demand.104, 105, 106 These cardiac effects are mediated by the activation of β1-adrenergic receptors, which are important in regulating heart function.107 However, to date no study has examined the effect of these different intensities of PA on β1-adrenergic receptors. This is a worthwhile future area of investigation to gain insight into how exercise intensity may affect cardiac function.

Vascular dysfunction, a hallmark of several cardiovascular diseases, is frequently associated with increased vasoconstriction and decreased vasodilation.108, 109 The current study demonstrated increased thoracic aortic contractile responses to noradrenaline in the SED group compared with the CTL group. This increased vascular reactivity to noradrenaline observed in the SED group supports previous observation that increased sedentary behavior promotes vascular deconditioning by increasing arterial tone.110 Studies have demonstrated that sedentary behavior increases plasma triglycerides and decreases HDL-C,29 whereas a high-fat diet is known to induce elevated levels of the triglyceride-rich very low-density lipoprotein and the cholesterol-rich LDL.111 Thus, this combined effect of sedentary behavior and diet is perhaps the reason for the increased α-adrenergic contractile responses (vascular constriction) observed in the SED group.112

In the mesenteric vessels, where vascular responsiveness is faster and greater compared with large vessels,113 the HIIT group (compared with CTL, SED, and LIT groups) had significantly lower contractile response to noradrenaline. These results are encouraging because they indicate that HIIT can mitigate mesenteric α-adrenergic contractile responses even with concurrent intake of an HFHC diet and can possibly decrease vessel pressure. Possible mechanism is the stimulation of an α-adrenergic receptor on the vascular endothelial cells, leading to release of endothelium-derived relaxing factor through the nitric oxide synthase pathway.114 This assumption is supported by the finding in this study of increased sensitivity of HIIT to endothelium-dependent mesenteric artery relaxation compared with the LIT group.

The present data also showed no between-group differences in endothelium-dependent aortic and endothelium-independent aortic and mesenteric relaxation after 12 weeks of intervention. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which demonstrated that an HFHC diet impairs endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent dilation, even in the absence of increase in fat mass.115 It has been suggested that the presence of insulin resistance and fatty acids released during fat oxidation, which activate the nuclear factor-κB resulting in nitric oxide inhibition, contribute to the impairment of the endothelium.116 Thus, it is possible that this HFHC diet is suppressing the effects of PA, if there are any.

5. Conclusion

The present study examined the influence of an HFHC diet on cardiometabolic, cardiac, and vascular function following 12 weeks of different intensities of PA in male adult rats. This study demonstrated negative effects on cardiac conduction and thoracic aortic contractile response in the SED group compared with the CTL group. LIT induced positive adaptations in fat accumulation and cardiac conduction compared with the CTL and SED groups, respectively. The HIIT group induced a positive effect on fat accumulation compared with the CTL group, a positive effect on mesenteric artery contraction compared with all other groups, and a positive effect on endothelium-dependent mesenteric artery relaxation compared with the LIT group. Our data provide evidence that few positive health effects are achieved through LIT and HIIT when consuming an HFHC diet. It is possible that the duration of the exercise interventions in this study is insufficient to prevent and/or reverse the changes occurring following HFHC feeding. Evidently, diet and PA play significant roles in influencing the cardiometabolic effect of LIT and HIIT and thus should both be targeted when developing interventions for improving cardiometabolic health.

Authors' contributions

RBB designed and conducted the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript; MJD contributed to the study design, data analysis, and manuscript drafting; VJD helped in data analysis and critically reviewed the manuscript; GLB contributed in data collection and data analysis; ASF helped with the study design and data analysis, edited and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kylie Connolly, Candice Pullen, and Douglas Jackson for their assistance during the terminal experiments and Dr. Jeff Coombes for allowing RBB to work in his laboratory for the F2-isoprostane analysis. RBB is supported by the Strategic Research Scholarship grant from Central Queensland University (CQU). This manuscript is in part supported by CQU Health CRN. MJD is supported by a Future Leader Fellowship (ID 100029) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

References

- 1.Hu F.B. Globalization of food patterns and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2008;118:1913–1914. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.808493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanoski S.E., Davidson T.L. Western diet consumption and cognitive impairment: links to hippocampal dysfunction and obesity. Physiol Behav. 2011;103:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dissard R., Klein J., Caubet C., Breuil B., Siwy J., Hoffman J. Long term metabolic syndrome induced by a high fat high fructose diet leads to minimal renal injury in C57BL/6 mice. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076703. e76703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lê K.A., Faeh D., Stettler R., Ith M., Kreis R., Vermathen P. A 4-wk high-fructose diet alters lipid metabolism without affecting insulin sensitivity or ectopic lipids in healthy humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1374–1379. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.6.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashen M.D. Management of cardiometabolic syndrome in the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. J Nurse Pract. 2008;4:673–680. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rangaraj V.R., Knutson K.L. Association between sleep deficiency and cardiometabolic disease: implications for health disparities. Sleep Med. 2016;18:19–35. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.02.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddigan J.I., Ardern C.I., Riddell M.C., Kuk J.L. Relation of physical activity to cardiovascular disease mortality and the influence of cardiometabolic risk factors. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1426–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekelund U., Franks P.W., Sharp S., Brage S., Wareham N.J. Increase in physical activity energy expenditure is associated with reduced metabolic risk independent of change in fatness and fitness. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2101–2106. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saunders T.J., Larouche R., Colley R.C., Tremblay M.S. Acute sedentary behaviour and markers of cardiometabolic risk: a systematic review of intervention studies. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/712435. 712435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norton K., Norton L., Sadgrove D. Position statement on physical activity and exercise intensity terminology. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson M.D., Al Snih S., Stoddard J., McClain J., Lee I.M. Adiposity and insufficient MVPA predict cardiometabolic abnormalities in adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:1133–1139. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández-García J.C., Cardona F., Tinahones F.J. Inflammation, oxidative stress and metabolic syndrome: dietary modulation. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2013;11:906–919. doi: 10.2174/15701611113116660175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lwow F., Dunajska K., Milewicz A., Jedrzejuk D., Kik K., Szmigiero L. Effect of moderate-intensity exercise on oxidative stress indices in metabolically healthy obese and metabolically unhealthy obese phenotypes in postmenopausal women: a pilot study. Menopause. 2011;18:646–653. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182038ec1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zoppini G., Targher G., Zamboni C., Venturi C., Cacciatori V., Moghetti P. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise training on plasma biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;16:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranadive S.M., Kappus R.M., Cook M.D., Yan H., Lane A.D., Woods J.A. Effect of acute moderate exercise on induced inflammation and arterial function in older adults. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:729–739. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.077636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starkie R., Ostrowski S.R., Jauffred S., Febbraio M., Pedersen B.K. Exercise and IL-6 infusion inhibit endotoxin-induced TNF-α production in humans. FASEB J. 2003;17:884–886. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0670fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews C.E., Chen K.Y., Freedson P.S., Buchowski M.S., Beech B.M., Pate R.R. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:875–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tremblay M.S., Colley R.C., Saunders T.J., Healy G.N., Owen N. Physiological and health implications of a sedentary lifestyle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010;35:725–740. doi: 10.1139/H10-079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Batacan R.B., Duncan M.J., Dalbo V.J., Tucker P.S., Fenning A.S. Effects of light intensity activity on CVD risk factors: a systematic review of intervention studies. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/596367. 596367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Church T.S., Thomas D.M., Tudor-Locke C., Katzmarzyk P.T., Earnest C.P., Rodarte R.Q. Trends over 5 decades in U.S. occupation-related physical activity and their associations with obesity. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019657. e19657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brownson R.C., Boehmer T.K., Luke D.A. Declining rates of physical activity in the United States: what are the contributors? Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:421–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhodes R.E., Mark R.S., Temmel C.P. Adult sedentary behavior: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.020. e3–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibala M.J., Little J.P., MacDonald M.J., Hawley J.A. Physiological adaptations to low-volume, high-intensity interval training in health and disease. J Physiol. 2012;590:1077–1084. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith K.L., Carr K., Wiseman A., Calhoun K., McNevin N.H., Weir P.L. Barriers are not the limiting factor to participation in physical activity in Canadian seniors. J Aging Res. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/890679. 890679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loprinzi P.D., Lee H., Cardinal B.J. Evidence to support including lifestyle light-intensity recommendations in physical activity guidelines for older adults. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29:277–284. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130709-QUAN-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buman M.P., Hekler E.B., Haskell W.L., Pruitt L., Conway T.L., Cain K.L. Objective light-intensity physical activity associations with rated health in older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1155–1165. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Healy G.N., Dunstan D.W., Salmon J., Cerin E., Shaw J.E., Zimmet P.Z. Objectively measured light-intensity physical activity is independently associated with 2-h plasma glucose. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1384–1389. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Healy G.N., Dunstan D.W., Shaw J.E., Zimmet P.Z., Owen N. Objectively measured sedentary time and light-intensity physical activity are independently associated with components of the metabolic syndrome: the AusDiab study. Diabetologia. 2008;50(Suppl. 1):S67–S68. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bey L., Hamilton M.T. Suppression of skeletal muscle lipoprotein lipase activity during physical inactivity: a molecular reason to maintain daily low-intensity activity. J Physiol. 2003;551:673–682. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.045591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler H.S., Sisson S.B., Short K.R. The potential for high-intensity interval training to reduce cardiometabolic disease risk. Sports Med. 2012;42:489–509. doi: 10.2165/11630910-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rocha R.E., Coelho I., Pequito D.C., Yamagushi A., Borghetti G., Yamazaki R.K. Interval training attenuates the metabolic disturbances in type 1 diabetes rat model. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2013;57:594–602. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302013000800003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoshino D., Yoshida Y., Kitaoka Y., Hatta H., Bonen A. High-intensity interval training increases intrinsic rates of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in rat red and white skeletal muscle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;38:326–333. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2012-0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nybo L., Sundstrup E., Jakobsen M.D., Mohr M., Hornstrup T., Simonsen L. High-intensity training versus traditional exercise interventions for promoting health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1951–1958. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181d99203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tjonna A.E., Lee S.J., Rognmo O., Stolen T.O., Bye A., Haram P.M. Aerobic interval training versus continuous moderate exercise as a treatment for the metabolic syndrome: a pilot study. Circulation. 2008;118:346–354. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.772822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Batacan R.B., Duncan M.J., Dalbo V.J., Connolly K.J., Fenning A.S. Light intensity and high intensity interval training improve cardiometabolic health in rats. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:945–952. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Look Ahead Research Group. Wadden T.A., West D.S., Delahanty L., Jakicic J., Rejeski J. The Look AHEAD Study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:737–752. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wadden T.A., Webb V.L., Moran C.H., Bailer B.A. Lifestyle modification for obesity: new developments in diet, physical activity, and behavior therapy. Circulation. 2012;125:1157–1170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Look Ahead Research Group. Wing R.R., Bolin P., Brancati F.L., Bray G.A., Clark J.M. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Physical activity and good nutrition: essential elements to prevent chronic diseases and obesity 2003. Nutr Clin Care. 2003;6:135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popkin B.M. Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:289–298. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nazni P. Association of western diet & lifestyle with decreased fertility. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140(Suppl. 1) S78–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pi-Sunyer F.X., Woo R. Effect of exercise on food intake in human subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:983–990. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/42.5.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Titchenal C.A. Exercise and food intake. What is the relationship? Sports Med. 1988;6:135–145. doi: 10.2165/00007256-198806030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharp J., Azar T., Lawson D. Does cage size affect heart rate and blood pressure of male rats at rest or after procedures that induce stress-like responses? Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2003;42:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee J.S., Bruce C.R., Spriet L.L., Hawley J.A. Interaction of diet and training on endurance performance in rats. Exp Physiol. 2001;86:499–508. doi: 10.1113/eph8602158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsunaga S., Yamada T., Mishima T., Sakamoto M., Sugiyama M., Wada M. Effects of high-intensity training and acute exercise on in vitro function of rat sarcoplasmic reticulum. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;99:641–649. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poudyal H., Panchal S., Brown L. Comparison of purple carrot juice and β-carotene in a high-carbohydrate, high-fat diet-fed rat model of the metabolic syndrome. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:1322–1332. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510002308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panchal S.K., Brown L. Rodent models for metabolic syndrome research. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/351982. 351982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fenning A., Harrison G., Rose'meyer R., Hoey A., Brown L. I-Arginine attenuates cardiovascular impairment in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00140.2005. H1408–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sorte K., Basak A. Development of a modified copper-cadmium reduction method for rapid assay of total nitric oxide. Anal Methods. 2010;2:944–947. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Friedlander Y., Kark J.D., Eisenberg S., Stein Y. Calculation of LDL-cholesterol from total cholesterol, triglyceride and HDL-cholesterol: a comparison of methods in the Jerusalem Lipid Research Clinic Prevalence Study. Isr J Med Sci. 1982;18:1242–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Briskey D.R., Wilson G.R., Fassett R.G., Coombes J.S. Optimized method for quantification of total F(2)-isoprostanes using gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2014;90:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bridges L.E., Williams C.L., Pointer M.A., Awumey E.M. Mesenteric artery contraction and relaxation studies using automated wire myography. J Vis Exp. 2011;22 doi: 10.3791/3119. 3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barnard R.J., Wen S.J. Exercise and diet in the prevention and control of the metabolic syndrome. Sports Med. 1994;18:218–228. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199418040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roberts C.K., Barnard R.J. Effects of exercise and diet on chronic disease. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:3–30. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00852.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Picchi M.G., Mattos A.M., Barbosa M.R., Duarte C.P., Gandini Mde A., Portari G.V. A high-fat diet as a model of fatty liver disease in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2011;26:25–30. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502011000800006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tillman E.J., Morgan D.A., Rahmouni K., Swoap S.J. Three months of high-fructose feeding fails to induce excessive weight gain or leptin resistance in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107206. e107206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crescenzo R., Bianco F., Coppola P., Mazzoli A., Cigliano L., Liverini G. The effect of high-fat–high-fructose diet on skeletal muscle mitochondrial energetics in adult rats. Eur J Nutr. 2015;54:183–192. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Charlton M., Krishnan A., Viker K., Sanderson S., Cazanave S., McConico A. Fast food diet mouse: novel small animal model of NASH with ballooning, progressive fibrosis, and high physiological fidelity to the human condition. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301 doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00145.2011. G825–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Panchal S.K., Poudyal H., Iyer A., Nazer R., Alam M.A., Diwan V. High-carbohydrate, high-fat diet–induced metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular remodeling in rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;57:611–624. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31821b1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poudyal H., Campbell F., Brown L. Olive leaf extract attenuates cardiac, hepatic, and metabolic changes in high carbohydrate-, high fat-fed rats. J Nutr. 2010;140:946–953. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.117812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vasselli J.R., Scarpace P.J., Harris R.B., Banks W.A. Dietary components in the development of leptin resistance. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:164–175. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramirez I. Feeding a liquid diet increases energy intake, weight gain and body fat in rats. J Nutr. 1987;117:2127–2134. doi: 10.1093/jn/117.12.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Touati S., Meziri F., Devaux S., Berthelot A., Touyz R.M., Laurant P. Exercise reverses metabolic syndrome in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:398–407. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181eeb12d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pinheiro-Mulder A., Aguila M.B., Bregman R., Mandarim-de-Lacerda C.A. Exercise counters diet-induced obesity, proteinuria, and structural kidney alterations in rat. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.EL-Gohary O.A., Hussien N.I. Effect of exercise and quercetin on obesity induced metabolic and renal impairments in albino rats. J Phys Pharm Adv. 2015;5:589–602. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Angelova P., Boyadjiev N. A review on the models of obesity and metabolic syndrome in rats. Trak J Sci. 2013;11:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Waveren A., Duncan M., Coulson F.R., Fenning A. Moderate intensity physical activity prevents increased blood glucose concentrations, fat pad deposition and cardiac action potential prolongation following diet-induced obesity in a juvenile-adolescent rat model. BMC Obes. 2014;1:11. doi: 10.1186/2052-9538-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moghadasian M.H., Abdullah M., Xu Z.Y., Othman R., Riediger N., Le K. Metabolic effects of long-term consumption of a high fat, high fructose diet in rats. FASEB J. 2007;21:A1091. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Medeiros R., Gaique T., Bernardes T., Motta N., Brito F., Bertoldi J. Aerobic training prevents the impaired vascular reactivity of fructose-treated rats. FASEB J. 2014;28:1106–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin S., Thomas T.C., Storlien L.H., Huang X.F. Development of high fat diet–induced obesity and leptin resistance in C57B1/6J mice. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:639–646. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kanarek R.B., Orthen-Gambill N. Differential effects of sucrose, fructose and glucose on carbohydrate induced obesity in rats. J Nutr. 1982;112:1546–1554. doi: 10.1093/jn/112.8.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Moura R.F., Ribeiro C., de Oliveira J.A., Stevanato E., de Mello M.A. Metabolic syndrome signs in Wistar rats submitted to different high-fructose ingestion protocols. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:1178–1184. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508066774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mamikutty N., Thent Z.C., Sapri S.R., Sahruddin N.N., Mohd Yusof M.R., Haji Suhaimi F. The establishment of metabolic syndrome model by induction of fructose drinking water in male Wistar rats. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/263897. 263897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peckham S.C., Entenman C. The influence of a hypercaloric diet on gross body and adipose tissue composition in the rat. J Nutr. 1962;77:187–197. doi: 10.1093/jn/77.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Herling A.W., Kilp S., Juretschke H.P., Neumann-Haefelin C., Gerl M., Kramer W. Reversal of visceral adiposity in candy-diet fed female Wistar rats by the CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant. Int J Obes. 2008;32:1363–1372. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Demerath E.W., Reed D., Rogers N., Sun S.S., Lee M., Choh A.C. Visceral adiposity and its anatomical distribution as predictors of the metabolic syndrome and cardiometabolic risk factor levels. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1263–1271. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boutcher S.H. High-intensity intermittent exercise and fat loss. J Obes. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/868305. 868305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Achten J., Jeukendrup A.E. Optimizing fat oxidation through exercise and diet. Nutrition. 2004;20:716–727. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Guilland J.C., Moreau D., Genet J.M., Klepping J. Role of catecholamines in regulation by feeding of energy balance following chronic exercise in rats. Physiol Behav. 1988;42:365–369. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rivest S., Richard D. Involvement of corticotropin-releasing factor in the anorexia induced by exercise. Brain Res Bull. 1990;25:169–172. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90270-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kaiyala K.J., Morton G.J., Thaler J.P., Meek T.H., Tylee T., Ogimoto K. Acutely decreased thermoregulatory energy expenditure or decreased activity energy expenditure both acutely reduce food intake in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041473. e41473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Triposkiadis F., Karayannis G., Giamouzis G., Skoularigis J., Louridas G., Butler J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure: physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1747–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Joyner M.J., Charkoudian N., Wallin B.G. Sympathetic nervous system and blood pressure in humans: individualized patterns of regulation and their implications. Hypertension. 2010;56:10–16. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li G., Liu J.Y., Zhang H.X., Li Q., Zhang S.W. Exercise training attenuates sympathetic activation and oxidative stress in diet-induced obesity. Physiol Res. 2015;64:355–367. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bertagnolli M., Schenkel P.C., Campos C., Mostarda C.T., Casarini D.E., Belló-Klein A. Exercise training reduces sympathetic modulation on cardiovascular system and cardiac oxidative stress in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:1188–1193. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schwartz J.H., Young J.B., Landsberg L. Effect of dietary fat on sympathetic nervous system activity in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:361–370. doi: 10.1172/JCI110976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Koshinaka K., Kawasaki E., Hokari F., Kawanaka K. Effect of acute high-intensity intermittent swimming on post-exercise insulin responsiveness in epitrochlearis muscle of fed rats. Metab Clin Exp. 2009;58:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cortez M.Y., Torgan C.E., Brozinick J.T., Ivy J.L. Insulin resistance of obese Zucker rats exercise trained at two different intensities. Am J Physiol. 1991;261 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.5.E613. E613–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fushiki T., Kano T., Inoue K., Sugimoto E. Decrease in muscle glucose transporter number in chronic physical inactivity in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1991;260 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.3.E403. E403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ravi Kiran T., Subramanyam M.V., Asha Devi S. Swim exercise training and adaptations in the antioxidant defense system of myocardium of old rats: relationship to swim intensity and duration. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;137:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sun M.W., Qian F.L., Wang J., Tao T., Guo J., Wang L. Low-intensity voluntary running lowers blood pressure with simultaneous improvement in endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and insulin sensitivity in aged spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:543–552. doi: 10.1291/hypres.31.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tucker P.S., Scanlan A.T., Dalbo V.J. High intensity interval training favourably affects angiotensinogen mRNA expression and markers of cardiorenal health in a rat model of early-stage chronic kidney disease. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/156584. 156584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cunha T.S., Moura M.J., Bernardes C.F., Tanno A.P., Marcondes F.K. Vascular sensitivity to phenylephrine in rats submitted to anaerobic training and nandrolone treatment. Hypertension. 2005;46:1010–1015. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000174600.51515.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Haram P.M., Kemi O.J., Lee S.J., Bendheim M.Ø., Al-Share Q.Y., Waldum H.L. Aerobic interval training vs. continuous moderate exercise in the metabolic syndrome of rats artificially selected for low aerobic capacity. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:723–732. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Williams L.M., Campbell F.M., Drew J.E., Koch C., Hoggard N., Rees W.D. The development of diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance in C57Bl/6 mice on a high-fat diet consists of distinct phases. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106159. e106159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Angelova P., Boyadjiev N., Georgieva K., Hrischev P. Effects of the application of a high-fat-carbohydrate diet without additional cholesterol for the inducement of metabolic syndrome in rats. Am Int J Contemp Res. 2013;3:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dinh Q.N., Drummond G.R., Sobey C.G., Chrissobolis S. Roles of inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/406960. 406960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Heitzer T., Schlinzig T., Krohn K., Meinertz T., Münzel T. Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2001;104:2673–2678. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.van den Oever I.A., Raterman H.G., Nurmohamed M.T., Simsek S. Endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and apoptosis in diabetes mellitus. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/792393. 792393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Barbosa V.A., Luciano T.F., Vitto M.F., Cesconetto P.A., Marques S.O., Souza D.R. Exercise training plays cardioprotection through the oxidative stress reduction in obese rats submitted to myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2012;157:422–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nakanishi R., Ohwaki J., Emoto S., Mori T., Mizuno K., Tsuda T. Nitric oxide concentrations in gas emanating from the tails of obese rats. Redox Rep. 2013;18:233–237. doi: 10.1179/1351000213Y.0000000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yan D., Cheng L.F., Song H.Y., Turdi S., Kerram P. Electrophysiological effects of haloperidol on isolated rabbit Purkinje fibers and guinea pigs papillary muscles under normal and simulated ischemia. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:1155–1160. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Clayton R.H., Bernus O., Cherry E.M., Dierckx H., Fenton F.H., Mirabella L. Models of cardiac tissue electrophysiology: progress, challenges and open questions. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;104:22–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wieneke H., Sattler K., von Birgelen C., Böse D., Haude M., Rechenberg W. Impact of intraventricular conduction delay on coronary haemodynamics: a study with intracoronary Doppler in patients with bundle branch blocks and normal coronary arteries. Europace. 2006;8:151–156. doi: 10.1093/europace/euj019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wallukat G. The β-adrenergic receptors. Herz. 2002;27:683–690. doi: 10.1007/s00059-002-2434-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhao Z., Luo Y., Li G., Zhu L., Wang Y., Zhang X. Thoracic aorta vasoreactivity in rats under exhaustive exercise: effects of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides supplementation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2013;10:47. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-10-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lundberg J.O., Gladwin M.T., Weitzberg E. Strategies to increase nitric oxide signalling in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:623–641. doi: 10.1038/nrd4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nosova E.V., Yen P., Chong K.C., Alley H.F., Stock E.O., Quinn A. Short-term physical inactivity impairs vascular function. J Surg Res. 2014;190:672–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang L., Xu F., Zhang X.J., Jin R.M., Li X. Effect of high-fat diet on cholesterol metabolism in rats and its association with Na+/K+-ATPase/Src/pERK signaling pathway. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2015;35:490–494. doi: 10.1007/s11596-015-1458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.West S.G. Effect of diet on vascular reactivity: an emerging marker for vascular risk. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2001;3:446–455. doi: 10.1007/s11883-001-0034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Davis M.J. Myogenic response gradient in an arteriolar network. Am J Physiol. 1993;264 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.6.H2168. H2168–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Minami K., Kashimura O. Exercise training inhibits vasoconstriction of the rat pulmonary artery. Adv Exerc Sports Physiol. 2004;10:71–75. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Naderali E.K., Williams G. Prolonged endothelial-dependent and -independent arterial dysfunction induced in the rat by short-term feeding with a high-fat, high-sucrose diet. Atherosclerosis. 2003;166:253–259. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Song G.Y., Gao Y., Di Y.W., Pan L.L., Zhou Y., Ye J.M. High-fat feeding reduces endothelium-dependent vasodilation in rats: differential mechanisms for saturated and unsaturated fatty acids? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:708–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]