Abstract

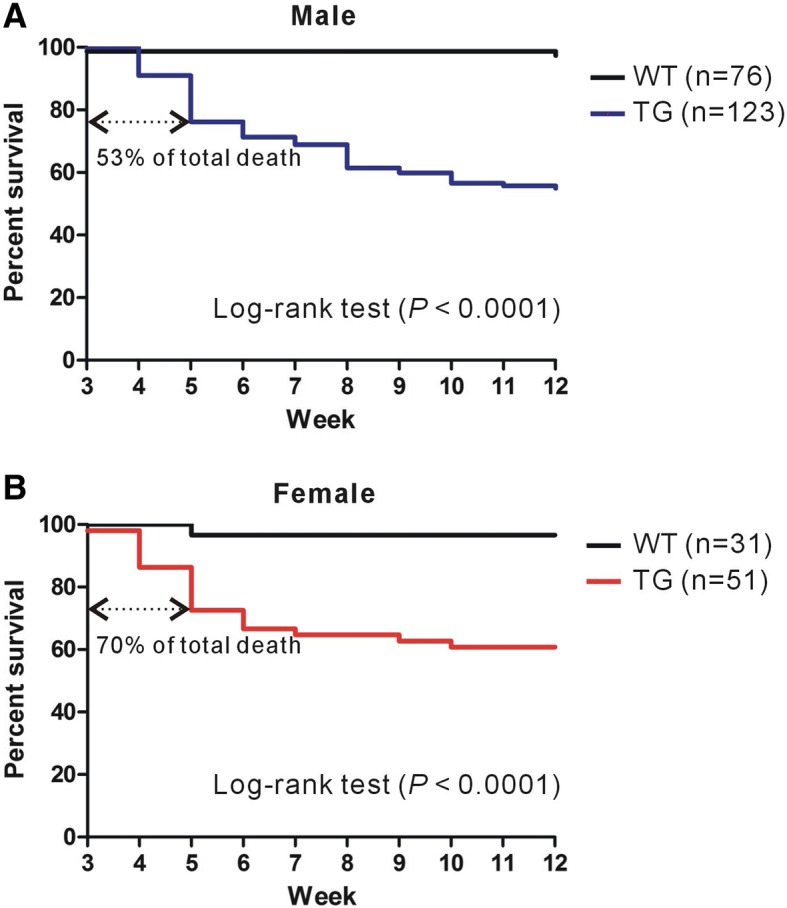

The SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3 (SHANK3) gene encodes core scaffolds in neuronal excitatory postsynapses. SHANK3 duplications have been identified in patients with hyperkinetic disorders and early-onset generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Consistently, Shank3 transgenic (TG) mice, which mildly overexpress Shank3 proteins exhibit hyperkinetic behavior and spontaneous seizures. However, the seizure phenotype of Shank3 TG mice has only been investigated in adults of the seizure-sensitive strain FVB/N. Therefore, it remains unknown if spontaneous seizures occur in Shank3 TG mice from the early postnatal stages onward, or even in seizure-resistant strains. Clinically, generalized tonic-clonic seizures are the critical risk factor for epilepsy-associated mortality. However, the potential association between Shank3 overexpression and mortality, at least in mice, has not been investigated in detail. In the present study, we backcrossed Shank3 TG mice in seizure-resistant C57BL/6 J strain and monitored their home-cage activities at 3 weeks of age. Of the 15 Shank3 TG mice monitored, two exhibited spontaneous tonic-clonic seizures, and one died immediately after the seizure event. Based on this observation, we determined the survival rate of the Shank3 TG mice from 3 to 12 weeks of age. We found that approximately 40–45% of the Shank3 TG mice, both males and females, died before reaching 12 weeks of age. Notably, 53% and 70% of the total deaths in male and female Shank3 TG mice, respectively, occurred in the juvenile stages. These results suggest spontaneous seizure and partial lethality of juvenile Shank3 TG mice in seizure-resistant background, further supporting the validity of this model.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13041-018-0403-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Shank3 overexpression, Spontaneous seizure, Lethality, Juvenile stage

Main text

Deletions, duplications, and various point mutations of the SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3 (SHANK3) gene, which encodes excitatory postsynaptic core scaffolding proteins [1], are causally associated with numerous neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), bipolar disorder, intellectual disability, and schizophrenia [2–4]. Specifically, we previously identified two SHANK3 duplication patients who presented with hyperkinetic disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and bipolar disorder, and early-onset generalized tonic-clonic seizures [4]. Furthermore, Shank3 transgenic (TG) mice which mildly overexpress Shank3 proteins (by approximately 50%), exhibit mania-like hyperkinetic behavior and spontaneous seizures, recapitulating the major symptoms seen in the patients [4–6].

However, the seizure phenotype has only been investigated in adult (8 to 12-week-old) Shank3 TG mice of FVB/N background which is a strain with high seizure sensitivity [7]. Therefore, it is unclear if spontaneous seizures occur in Shank3 TG mice from the early postnatal stages, as in the patients, and even in other seizure-resistant strains, such as C57BL/6 J [7, 8]. Moreover, from a clinical perspective, generalized tonic-clonic seizures are the critical risk factor for epilepsy-associated mortality, such as sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) [9]. Although the two SHANK3 duplication patients commonly showed generalized tonic-clonic seizures, the potential association between Shank3 overexpression and lethality, at least in Shank3 TG mice, has not been investigated in detail.

To address these issues, we crossed Shank3 TG mice of FVB/N strain with wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 J mice for more than ten generations. To examine behavioral seizures in the early postnatal stages, we monitored the home-cage activities of juvenile (3-week-old) Shank3 TG mice twice per day (at 10 am and 4 pm, for one hour per each session) for a week. Of the 15 Shank3 TG mice monitored, we found two mice exhibiting spontaneous behavioral seizures. During the seizures, both mice showed rearing, jumping, and falling with forelimb clonus (Additional file 1), which is the behavioral indication of tonic-clonic seizure (Racine’s scale 5) [10]. Notably, one of the Shank3 TG mice died immediately after a single seizure event during our observation. None of the ten WT littermates showed any sign of behavioral seizure during a week of monitoring.

Additional file 1:

Spontaneous seizure of juvenile Shank3 transgenic mice in C57BL/6J strain. This video shows spontaneous seizure from an 3-week-old Shank3 transgenic mouse in C57BL/6J strain. (MP4 6987 kb)

Based on our observation of the death of the Shank3 TG mouse after spontaneous seizure, we determined the survival rates of the male and female Shank3 TG mice, and those of their WT littermates, from postnatal 3 to 12 weeks of age. Of a total of 123 male and 51 female Shank3 TG mice, approximately 40–45% (55 males and 20 females) died before they reached 12 weeks of age (Fig. 1a, b). Furthermore, 53% and 70% of total death in male and female Shank3 TG mice, respectively, occurred in juvenile stages (between 3 and 5 weeks of age), which is consistent with our observation of the spontaneous seizure and subsequent death of a 3-week-old Shank3 TG mouse. Two male (2.6% of 76) and one female (3.2% of 31) WT mice died during our counting from unknown cause.

Fig. 1.

Survival plots of male and female wild-type (WT) and Shank3 transgenic (TG) mice in C57BL/6 J background. a Survival plot of male WT (black line) and Shank3 TG (blue line) mice from 3 to 12 weeks of age. Of the 123 Shank3 TG mice, 55 died before the age of 12 weeks, and 29 (53%) died before the age of 5 weeks. Two WT mice died during counting (Log-rank test, P < 0.0001). b Survival plot of female WT (black line) and Shank3 TG (red line) mice. Of the 51 Shank3 TG mice, 20 died before the age of 12 weeks, and 14 (70%) died before the age of 5 weeks. One WT mouse died during counting (Log-rank test, P < 0.0001). Numbers for the survival plots are provided in Additional file 2

These results suggest that Shank3 TG mice exhibit spontaneous seizures from the early juvenile stages, and even by seizure-resistant C57BL/6 J strain, which, together with their hyperkinetic behavior, further supports the face validity [11] of these mice for modeling human SHANK3 duplications. We did not expect that up to 40–45% of the Shank3 TG mice would die before the age of 12 weeks. Clinically, SUDEP is the most common cause of mortality in patients with epilepsy [9]. Thus far, several genetic models of SUDEP have been established in which mostly ion channel genes are deleted or mutated [12]. If sufficiently validated, we believe that Shank3 TG mice may provide a unique SUDEP or epilepsy-associated lethality model with an excitatory and inhibitory synaptic imbalance [4, 13], rather than ion channel dysfunction. However, further detailed investigations, including simultaneous electroencephalography (EEG) and electrocardiogram (ECG) measurements [14], are required to confirm the causal relationship between seizure and lethality in Shank3 TG mice.

Additional files

Supplementary materials and methods, and tables. This file includes information about the mice used in this study, and tables of numbers for the survival plots. (DOCX 27 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank the Laboratory Animal Research Center at Korea University College of Medicine for their animal care and support.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea Government Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2015M3C7A1028790, NRF-2018R1C1B6001235 and NRF-2018M3C7A1024603).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- ASDs

Autism spectrum disorders

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- EEG

Electroencephalography

- SHANK3

SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3

- SUDEP

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy

- TG

Transgenic

Authors’ contributions

CJ, YZ, SK, YK, YL and KH designed and performed the experiments. CJ and KH analyzed and interpreted the data. KH wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval

The WT and Shank3 TG mice were bred and maintained in a C57BL/6 J background according to the Korea University College of Medicine Research Requirements, and all the experimental procedures were approved by the Committees on Animal Research at the Korea University College of Medicine (KOREA-2016-0096).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chunmei Jin, Email: jinchunmei777@naver.com.

Yinhua Zhang, Email: eunhwa428@korea.ac.kr.

Shinhyun Kim, Email: shinhyun1994@gmail.com.

Yoonhee Kim, Email: uni816@korea.ac.kr.

Yeunkum Lee, Email: yeunkumlee@gmail.com.

Kihoon Han, Phone: +82-2-2286-1390, Email: neurohan@korea.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Sheng M, Kim E. The Shank family of scaffold proteins. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 11):1851–1856. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.11.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grabrucker AM, Schmeisser MJ, Schoen M, Boeckers TM. Postsynaptic ProSAP/Shank scaffolds in the cross-hair of synaptopathies. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21(10):594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leblond CS, Nava C, Polge A, Gauthier J, Huguet G, Lumbroso S, et al. Meta-analysis of SHANK mutations in autism Spectrum disorders: a gradient of severity in cognitive impairments. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(9):e1004580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han Kihoon, Holder Jr J. Lloyd, Schaaf Christian P., Lu Hui, Chen Hongmei, Kang Hyojin, Tang Jianrong, Wu Zhenyu, Hao Shuang, Cheung Sau Wai, Yu Peng, Sun Hao, Breman Amy M., Patel Ankita, Lu Hui-Chen, Zoghbi Huda Y. SHANK3 overexpression causes manic-like behaviour with unique pharmacogenetic properties. Nature. 2013;503(7474):72–77. doi: 10.1038/nature12630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi S-Y, Han K. Emerging role of synaptic actin-regulatory pathway in the pathophysiology of mood disorders. Animal Cells Syst (Seoul) 2015;19(5):283–288. doi: 10.1080/19768354.2015.1086435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y, Zhang Y, Kim S, Han K. Excitatory and inhibitory synaptic dysfunction in mania: an emerging hypothesis from animal model studies. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50(4):12. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0028-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankel WN, Taylor L, Beyer B, Tempel BL, White HS. Electroconvulsive thresholds of inbred mouse strains. Genomics. 2001;74(3):306–312. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferraro TN, Golden GT, Smith GG, DeMuth D, Buono RJ, Berrettini WH. Mouse strain variation in maximal electroshock seizure threshold. Brain Res. 2002;936(1–2):82–86. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)02565-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devinsky O, Hesdorffer DC, Thurman DJ, Lhatoo S, Richerson G. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(10):1075–1088. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32(3):281–294. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(10):1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/nn.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman Alica M., Buchanan Gordon, Aiba Isamu, Noebels Jeffrey L. Models of Seizures and Epilepsy. 2017. SUDEP Animal Models; pp. 1007–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee B, Zhang Y, Kim Y, Kim S, Lee Y, Han K. Age-dependent decrease of GAD65/67 mRNAs but normal densities of GABAergic interneurons in the brain regions of Shank3-overexpressing manic mouse model. Neurosci Lett. 2017;649:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalume F, Westenbroek RE, Cheah CS, Yu FH, Oakley JC, Scheuer T, et al. Sudden unexpected death in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(4):1798–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI66220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials and methods, and tables. This file includes information about the mice used in this study, and tables of numbers for the survival plots. (DOCX 27 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.