Abstract

Background:

Thoracotomy needs adequate powerful postoperative analgesia. This study aims to compare the safety and efficacy of ultrasound (US)-guided serratus anterior plane block (SAPB) and thoracic paravertebral block (TPVB) for perioperative analgesia in cancer patients having lung lobectomy.

Patients and Methods:

This clinical trial involved 90 patients with lung cancer scheduled for lung lobectomy randomly divided into three groups according to the type of preemptive regional block. Group TPVB received US-guided TPVB. In Group SAPB, US-guided SAPB was performed. The patients of the control Group received general anesthesia alone. The outcome measures were postoperative visual analog scale (VAS) score, intraoperative fentanyl consumption, time of first rescue analgesic, total dose postoperative analgesic, and drug-related adverse effects.

Results:

Analgesia was adequate in TPVB and SAPB groups up to 24 h. VAS score was comparable in TPVB and SAPB groups and significantly lower compared to control group up to 9 h postoperatively. At 12 and 24 h, TPVB group had significantly lower VAS score relative to SAPB and control groups. Total intraoperative fentanyl consumption was significantly lower in TPVB and SAPB Groups compared to control group. The majority of TPVB Group cases did not need rescue morphine, while the majority of control group needed two doses (P < 0.001). The hemodynamic variables were stable in all patients. Few cases reported trivial adverse effects.

Conclusion:

Preemptive TPVB and SAPB provide comparable levels of adequate analgesia for the first 24 h after thoracotomy. TPVB provided better analgesia after 12 h. The two procedures reduce intraoperative fentanyl and postoperative morphine consumption.

Keywords: Acute, paravertebral block, postthoracotomy pain, serratus plane block, thoracotomy

Introduction

The management of pathologies involving the lungs, mediastinum, or esophagus involves thoracic surgical incision which may be posterolateral, anterolateral, or anterior.[1] Postthoracotomy pain affects 30%–50% of the patients undergoing thoracotomy.[2] Poorly managed pain following thoracotomy can lead to increase the risk of complications such as lung collapse and chest infections due to altered mechanical functions of the lungs and ventilation-perfusion mismatch.[3]

Acute thoracotomy pain is multifactorial in nature. It involves nociceptive and neuropathic mechanisms originating from somatic and visceral afferents. The main sources of pain are intercostal nerves, the vagus nerve and phrenic nerve in the pleura, the superficial cervical plexus, and the brachial plexus in the ipsilateral shoulder.[4]

Therefore, a multimodal analgesic approach is recommended to combat the multiple pain sites. It usually combines systemic analgesia with opioid and nonopioid medications with regional anesthetic techniques. These include intercostal nerve block, thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA), and thoracic paravertebral blocks (TPVB).[5]

TEA is considered as the gold standard for thoracotomy pain.[4] However, according to a recent systematic review, TPVB has been shown to be as effective as TEA with reduction of the risks of minor complications compared to TEA.[6] Serratus anterior plane block (SAPB) is another alternative for relief of thoracotomy pain. It is performed under ultrasonography guidance to provide analgesia between the levels of thoracic 2 and 9.[7]

This study aimed to compare the safety and efficacy of ultrasound (US)-guided SAPB and TPVB for perioperative analgesia in cancer patients having lung lobectomy.

Patients and Methods

The study involved 90 patients with lung cancer scheduled for lung lobectomy in the Department of Surgery at National Cancer Institute, Cairo University. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Anesthesia Department. All patients were fully informed about the nature, tools, and techniques of the study before providing informed consents to participate.

Inclusion criteria were age between 40 and 60 years and The American Society of Anesthesiologists Class I or II. Patients with local infection at the puncture site, coagulopathy, or cognitive disorders were excluded from the study.

All patients were scheduled for surgery under general anesthesia. Using computer-generated random numbers, the patients were randomly allocated into one of three treatment groups according to the regional block used. In Group TPVB, after induction of anesthesia and before surgical incision, TPVB using bupivacaine was done under US guidance. In Group SAPB, US-guided serratus anterior plane block using bupivacaine was performed after induction of anesthesia and before surgical incision. The third group, Group C was the control group where the patients received general anesthesia alone.

Anesthetic technique

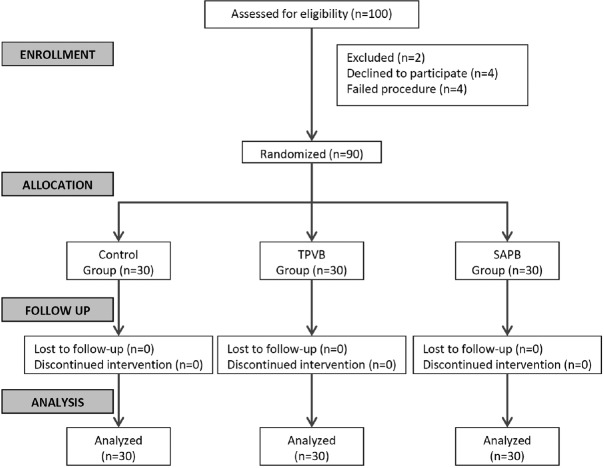

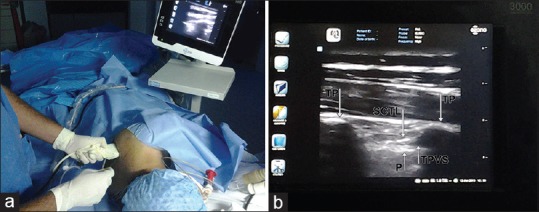

A peripheral intravenous (IV) access was established. The patients were premedicated with IV midazolam (0.05 mg/kg). Under standard monitoring including electrocardiography, noninvasive blood pressure, and pulse oximetry preoxygenation were done for 5 min, and general anesthesia was induced with fentanyl (1–2 μg/kg), propofol 2–3 mg/kg, and rocuronium 0.5–0.8 mg/kg. Volume-controlled ventilation mode was used to maintain O2 saturation above 98% and ETCO2 around 30–35 mmHg. Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane 1 minimum alveolar concentration inhalation. For TPVB, a US probe was placed longitudinally over a spinous process in the midline and moved laterally to visualize the transverse process. At the point of intersection of the transverse process and the rib, the superior costotransverse ligament and the pleura with lung tissue were visualized anteriorly. The probe was turned in a lateral transverse manner to visualize the transverse process, pleura, and lung tissue. A 20G blunt-tipped needle was introduced cephalad, and its tip was advanced under direct visualization until it is directly above the pleura. Then, the needle was aspirated to confirm the absence of blood or air. Subsequently, 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine is injected in 3–4 ml increments at the level of T5 [Figure 1]. SAPB was done with the patient in the lateral position and the diseased side up. A linear US probe (13–16 MHz) was placed over the midclavicular region of the thoracic cage in a sagittal plane. The fifth rib was identified in the midaxillary line. Overlying the fifth rib, three muscles were identified: the latissimus dorsi (superficial and posterior), teres major (superior), and serratus anterior muscle (deep and inferior). The needle was put in plane with the US probe and was advanced from posterior to anterocaudal direction to reach the plane superficial to serratus anterior muscle. Under continuous US guidance, 30 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine were injected [Figure 2]. Intraoperatively, the blood pressure and heart rate were recorded every 30 min. At the end of surgery, the total fentanyl consumption was recorded. Time taken to finish the block was measured from just after draping of the patient to the end of the block.

Figure 1.

Thoracic paravertebral block procedure. (a) The needle and probe position, (b) ultrasonographic image of paravertebral space. TP: Transverse process; SCTL: Superior costotransverse ligament; TPVS: Thoracic paravertebral space; P: Pleura

Figure 2.

Serratus anterior plane block procedure. (a) The needle and probe position, (b) ultrasonographic picture of serratus anterior plane, (c) arrow pointing to the local anesthetic injected between serratus anterior muscle and latissimus dorsi. LD: Latissimus dorsi; SA: Serratus anterior; P: Pleura

During the postoperative period, data were collected by an anesthesia resident blinded to the patient allocation. Data included visual analog scale (VAS) score for pain immediately postoperative and 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h afterward, Ramsay sedation score 15 min postoperatively (1–6 score where 1 denotes anxious, restless, or both and 6 denotes no response to stimuli), mean arterial pressure, and heart rate. Measurements were recorded up to 24-postoperative h.

A rescue analgesic was given when the VAS score exceeded 4 in the form of ketorolac 30 mg. For a VAS above 5, a 3-mg dose of morphine was given. The time of the first rescue analgesic and the total dose of the given drug throughout the 24 h were recorded.

Adverse effects of opioids and local anesthetics were recorded including respiratory depression (respiratory rate <8 breath/min and SpO2 <90%), bradycardia, and hypotension. Postoperative nausea and vomiting scores (0-none, 1-mild, 2-moderate, and 3-severe) were recorded.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was postoperative pain intensity expressed as VAS score. Secondary outcome measures were intraoperative fentanyl consumption, time of first rescue analgesic, total dose postoperative analgesic, and drug-related adverse effects.

Sample size estimation

According to previous studies, to see a difference in VAS score of 1.1 between serratus plane block with a median VAS of 2[8] and paravertebral block of 3.1 (2–5)[9] with a pooled standard deviation of 0.5, an alpha error off 0.01 and power of a test of 90%, minimum number of patients needed would be eight per group. To assume normality of distribution and increase the power of the test, 30 patients per group were included in this study.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was done using IBM© SPSS© Statistics version 22 (IBM© Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Numerical data were expressed as a mean and standard deviation or median and range as appropriate. Qualitative data were expressed as frequency and percentage. Chi-square test (Fisher's exact test) was used to examine the relationship between qualitative variables. For quantitative data, comparison between the three groups was done using ANOVA test or Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by the appropriate post hoc test. Comparison of repeated measures was done using ANOVA for repeated measures or Friedman test followed by Wilcoxon signed-ranks test. P values were corrected due to repeated analyses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

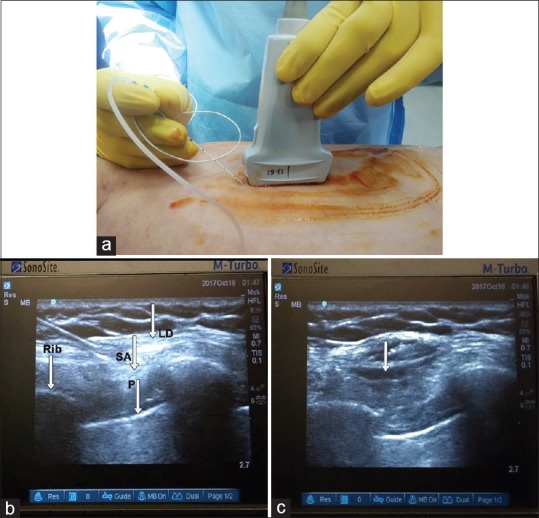

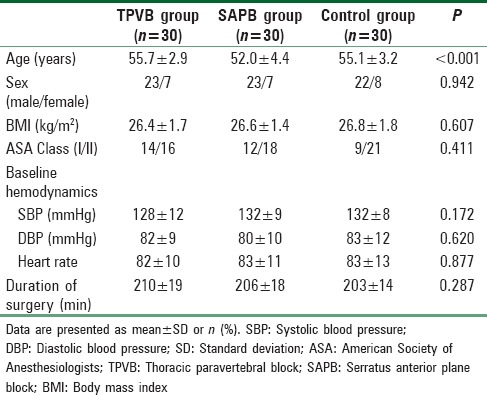

One-hundred patients were assessed for eligibility; 10 were excluded [Figure 3]. The results are presented for the remaining 90 patients. Table 1 shows that there was no significant difference in baseline characteristic between the three studied groups except age (P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

CONSORT flow diagram

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of the two studied groups

Outcome

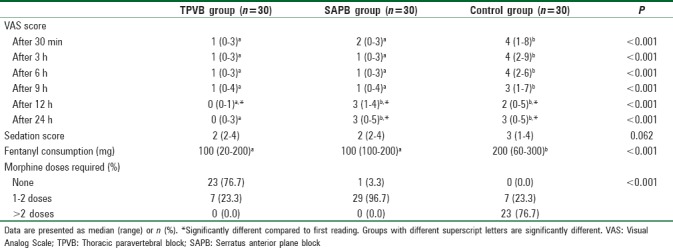

Analgesia was adequate in TPVB and SAPB Groups up to 24 h after surgery. VAS score was comparable in TPVB and SAPB Groups and significantly lower compared to control group between 30 min and 9 h postoperatively [Table 2]. At 12 and 24 h, TPVB group had significantly lower VAS score relative to SAPB and control groups. Total intraoperative fentanyl consumption was significantly lower in TPVB and SAPB Groups compared to control group. The majority of TPVB group cases did not need rescue morphine doses, while the majority of control Group needed two doses (P < 0.001). Sedation score after 15 min was comparable in the three groups (P = 0.062).

Table 2.

Quality of analgesia during the postoperative period in the two studied groups

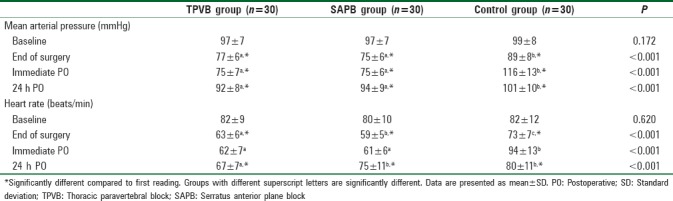

As shown in Table 3, the blood pressure and heart rate showed statistically significant changes during intraoperative and postoperative periods in the three groups. However, all readings were within the clinically accepted ranges.

Table 3.

Changes of mean arterial pressure and heart rate during the intraoperative and first 24 postoperative hours in the three studied groups

In TPVB group, there was one case of bradycardia, four cases of hypotension, and another case of nausea and vomiting. In SAPB group, one patient suffered nausea and vomiting.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that TPVB and SAPB before surgical incision provided adequate analgesia for the first 24 h after thoracotomy. Pain intensity was significantly lower with TPVB compared to SAPB after 12 h. During surgery, TPVB and SAPB significantly reduced fentanyl consumption compared to control Group. Morphine consumption was significantly reduced in TPVB group compared to SAPB group and control group. Both regional techniques were hemodynamically safe with minor adverse effects. Few patients developed bradycardia and hypotension in TPVB Group.

The search for a safe and effective regional technique for pain management in thoracic surgery continues aiming to reduce the undesirable adverse effects of opioid use in such cases. Incremental doses of opioids have many disadvantages including respiratory depression, pruritus, sedation, and nausea or vomiting.[10]

In this study, we adopted the concept of preemptive analgesia through the application of regional blocks before surgical incision. This approach focuses on postoperative analgesia in addition to prevention of central sensitization and chronic neuropathic pain.[11] This is a vital issue in surgeries involving a thoracotomy incision as chronic pain after thoracic surgery is a common clinical problem in 25%–60% of patients.[12]

A recent systematic review reported better pain control and greater patient satisfaction up to 18–24 h after injection in TPVB compared to systemic opioids. This was accompanied by more stable hemodynamics and less side effect.[13] The overall complications rate after paravertebral blocks was reported to be 2.6% to 5%.[14] These complications include hypotension (4.6%), vascular puncture (3.8%), pleural puncture (1.1%), and pneumothorax (0.5%).[15]

In view of its easier application and lower complication rate, we compared the US-guided SAPB with TPVB. In SAPB, the local anesthetic can be injected superficial or deep to the serratus anterior muscle. In the current study, we used the superficial technique. The results of this study were in favor of TPVB regarding the analgesic efficacy and longer duration of pain control. On the other hand, SAPB appeared to be more safe in view of the lower rate of adverse events especially hypotension and bradycardia.

The relatively short duration of analgesia after SAPB has been previously reported.[7,16] Continuous SAPB with catheter placement is suggested to prolong its analgesic duration.[17,18]

In a recent retrospective study, it was concluded that the SAPB is an effective adjuvant for thoracotomy analgesia. The authors used a multimodal approach using a combination of IV patient-controlled analgesia with morphine and SAPB.[19] In fact, the current study showed administration of one or two doses of morphine during the 24-postoperative h for all except one patient in the SAPB Group. The control Groups required higher doses of morphine. Therefore, SAPB reduced morphine consumption but was not adequate as the only postoperative analgesic.

Efficacy of SAPB has been reported by other investigators in cases of esophagectomy,[8] rib fracture,[20,21] and lung cancer[22] with a reasonable safety profile. A recent randomized controlled study compared SAPB with TEA for controlling acute thoracotomy pain. The authors applied SAPB before extubation, and TEA was activated before extubation. Both techniques provided comparable pain control and morphine consumption, but SAPB was hemodynamically more stable than TEA.[22]

Gupta et al.[23] compared TPVB and SAPB for pain control after modified radical mastectomy. Similar to the current study, TPVB was associated with longer duration of analgesia and significantly lower morphine consumption. In a recent case report, SAPB had the advantage of providing analgesia for chest tube-related pain compared to TPVB.[24] In patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy, pectoralis-serratus interfascial plane block provided good analgesia, but inferior to TPVB.[25]

Conclusion

Preemptive TPVB and SAPB provide adequate levels of analgesia for the first 24-postoperative h after thoracotomy. The two procedures were provided comparable pain reduction up to 9 h postoperatively. After 12 h, TPVB provided lower pain intensity. Intraoperative fentanyl consumption and postoperative morphine consumption was reduced in association with TPVB and SAPB. Hemodynamically, the two procedures were safe with few side effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Koehler RP, Keenan RJ. Management of postthoracotomy pain: Acute and chronic. Thorac Surg Clin. 2006;16:287–97. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Humble SR, Dalton AJ, Li L. A systematic review of therapeutic interventions to reduce acute and chronic post-surgical pain after amputation, thoracotomy or mastectomy. Eur J Pain. 2015;19:451–65. doi: 10.1002/ejp.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doan LV, Augustus J, Androphy R, Schechter D, Gharibo C. Mitigating the impact of acute and chronic post-thoracotomy pain. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28:1048–56. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okmen K, Okmen BM, Uysal S. Serratus anterior plane (SAP) block used for thoracotomy analgesia: A case report. Korean J Pain. 2016;29:189–92. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2016.29.3.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiss G, Castillo M. Non-intubated anesthesia in thoracic surgery-technical issues. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:109. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.05.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeung JH, Gates S, Naidu BV, Wilson MJ, Gao Smith F. Paravertebral block versus thoracic epidural for patients undergoing thoracotomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009121. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009121.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanco R, Parras T, McDonnell JG, Prats-Galino A. Serratus plane block: A novel ultrasound-guided thoracic wall nerve block. Anaesthesia. 2013;68:1107–13. doi: 10.1111/anae.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madabushi R, Tewari S, Gautam SK, Agarwal A, Agarwal A. Serratus anterior plane block: A new analgesic technique for post-thoracotomy pain. Pain Physician. 2015;18:E421–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogt A, Stieger DS, Theurillat C, Curatolo M. Single-injection thoracic paravertebral block for postoperative pain treatment after thoracoscopic surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:816–21. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michelet P, Guervilly C, Hélaine A, Avaro JP, Blayac D, Gaillat F, et al. Adding ketamine to morphine for patient-controlled analgesia after thoracic surgery: Influence on morphine consumption, respiratory function, and nocturnal desaturation. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:396–403. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vadivelu N, Mitra S, Schermer E, Kodumudi V, Kaye AD, Urman RD, et al. Preventive analgesia for postoperative pain control: A broader concept. Local Reg Anesth. 2014;7:17–22. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S62160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wildgaard K, Ravn J, Kehlet H. Chronic post-thoracotomy pain: A critical review of pathogenic mechanisms and strategies for prevention. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;36:170–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gessling EA, Miller M. Efficacy of thoracic paravertebral block versus systemic analgesia for postoperative thoracotomy pain: A systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15:30–8. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tighe SQ, Greene MD, Rajadurai N. Paravertebral block. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2010;10:133–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coveney E, Weltz CR, Greengrass R, Iglehart JD, Leight GS, Steele SM, et al. Use of paravertebral block anesthesia in the surgical management of breast cancer: Experience in 156 cases. Ann Surg. 1998;227:496–501. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbera C, Milito P, Punturieri M, Asti E, Bonavina L. Serratus anterior plane block for hybrid transthoracic esophagectomy: A pilot study. J Pain Res. 2017;10:73–7. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S121441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broseta AM, Errando C, De Andrés J, Díaz-Cambronero O, Ortega-Monzó J. Serratus plane block: The regional analgesia technique for thoracoscopy? Anaesthesia. 2015;70:1329–30. doi: 10.1111/anae.13263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujiwara S, Komasawa N, Minami T. Pectral nerve blocks and serratus-intercostal plane block for intractable postthoracotomy syndrome. J Clin Anesth. 2015;27:275–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ökmen K, Ökmen BM. The efficacy of serratus anterior plane block in analgesia for thoracotomy: A retrospective study. J Anesth. 2017;31:579–85. doi: 10.1007/s00540-017-2364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durant E, Dixon B, Luftig J, Mantuani D, Herring A. Ultrasound-guided serratus plane block for ED rib fracture pain control. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:197, 197.e3–197.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu P, Weyker PD, Webb CA. Case report of serratus plane catheter for pain management in a patient with multiple rib fractures and an inferior scapular fracture. A A Case Rep. 2017;8:132–5. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khalil AE, Abdallah NM, Bashandy GM, Kaddah TA. Ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block versus thoracic epidural analgesia for thoracotomy pain. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31:152–8. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2016.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta K, Srikanth K, Girdhar KK, Chan V. Analgesic efficacy of ultrasound-guided paravertebral block versus serratus plane block for modified radical mastectomy: A randomised, controlled trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2017;61:381–6. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_62_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu GM, Jarvis GC. Serratus anterior plane block to address postthoracotomy and chest tube-related pain: A report on 3 cases. A A Case Rep. 2017;8:322–5. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hetta DF, Rezk KM. Pectoralis-serratus interfascial plane block vs. thoracic paravertebral block for unilateral radical mastectomy with axillary evacuation. J Clin Anesth. 2016;34:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]