Abstract

Purpose

In response to the increasing cancer burden in Kenya, this study identified barriers to patients seeking access to cancer testing and treatment and to clinicians in delivering these services. Policy recommendations based on findings are presented.

Methods

This qualitative study used semistructured key informant interviews. Purposive sampling was used to recruit 14 participants: seven oncology clinicians and seven support and advocacy leaders for patients with cancer. Qualitative analysis was used to identify themes.

Results

Seven barriers to cancer testing and treatment were identified: high cost of testing and treatment, low level of knowledge about cancer among population and clinicians, poor health-seeking behaviors among population, long distances to access diagnostic and treatment services, lack of decentralized diagnostic and treatment facilities, poor communication, and lack of better cancer policy development and implementation.

Conclusion

Kenyans seeking cancer services face significant barriers that result in late presentation, misdiagnosis, interrupted treatment, stigma, and fear. Four policy recommendations to improve access for patients with cancer are (1) improve health insurance for patients with cancer; (2) establish testing and treatment facilities in all counties; (3) acquire diagnosis and treatment equipment and train health personnel to screen, diagnose, and treat cancer; and (4) increase public health awareness and education about cancer to improve diagnoses and treatment. Effective cancer testing and treatment options can be developed to address cancer in a resource-constrained environment like Kenya. An in-depth look at effective interventions and policies being implemented in countries facing similar challenges would provide valuable lessons to Kenya’s health sector and policymakers.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of cancer is increasing worldwide. The International Agency for Research on Cancer , a WHO agency, reported 14.1 million new cancer cases, 8.2 million deaths resulting from cancer, and 32.6 million people living with cancer (within 5 years of diagnosis) worldwide in 2012. Of these, 8 million new cancer cases (57%) and 5.3 million deaths resulting from cancer (65%) occurred in less developed regions.1

Cancer is the third-leading cause of death in Kenya. Some 22,0002 to 41,000 new cases occur each year,3 and 28,000 Kenyans die as a result of cancer each year.4 In Kenya, 60% of patients with cancer are ≤ 60 years of age.2 Whereas 48% of the deaths resulting from cancer in low- or middle-income countries are premature (younger than 70 years of age), only 26% fall under the same category in high-income countries.5 Cancer poses unique challenges to Kenya’s health infrastructure and affects a much younger population than elsewhere.

Kenya currently has limited personnel and only 12 facilities to diagnose and treat cancer, which include seven private hospitals, two mission hospitals, and three public facilities. It has four radiotherapy centers,6 mostly located in urban areas. Among the public facilities, only Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) is equipped to provide the three major cancer treatment modalities: surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy (chemotherapy). The other two public facilities—Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) in Eldoret and Coast General Hospital—provide surgery and systemic therapy, with plans to add radiotherapy units in future. Three private hospitals—MP Shah, Aga Khan, and Nairobi Hospitals—provide all treatment modalities, whereas the other private hospitals provide only surgery and systemic therapy.

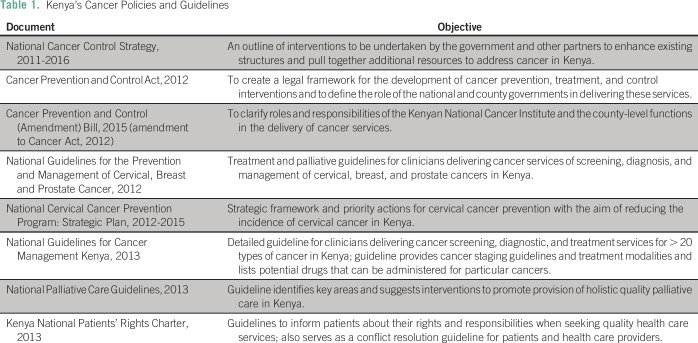

Kenya’s first cancer treatment, control, and prevention policy was developed in 2011.2 This was followed by the 2012 Cancer Act7 (amended in 20158) governing the establishment of a national cancer institute and the decentralization of prevention and treatment activities through the counties. The National Guidelines for Cancer Management were created in 2013.9 These policy documents and actions laid the framework for addressing Kenya’s cancer burden.

In 2015, Kenya’s public insurer, the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF), initiated coverage of up to KSh5,000,000 (US$50,000) for patients with cancer who needed urgent treatment outside the country. In October 2016,10 NHIF reviewed the policy to include cancer treatment within the country and to reduce long wait times in NHIF-participating hospitals. In March 2017, Kenya’s Ministry of Health held a cancer stakeholder consultative group meeting to draft the 2017 to 2022 National Cancer Control Policy. This policy, still under review, aims to address the limitations of policies reviewed in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Kenya’s Cancer Policies and Guidelines

Prior research on patients with cancer and service providers in Kenya pointed to medical costs as a significant barrier to accessing testing and treatment services for all types of cancers. Patients covered under NHIF were more likely to complete treatment as compared with those without insurance.11-13 Poor provider attitudes and stigma for patients seeking cervical cancer screening were commonly cited as deterrents to screening and treatment.14,15 Additional barriers included the lack of provider skills; equipment for screening, diagnosis, and treatment; and supplies. These contributed to late presentation by patients.16,17

High costs of transportation to medical facilities, lack of parental awareness about cancer, poor communication by providers, and scarcity of pediatric oncologic services were major barriers faced by parents of children with pediatric neoplasms.11,13,18 Insured patients had higher treatment completion rates and higher chances of event-free survival 2 years after treatment, as compared with uninsured patients.14,19Provider-side barriers included a lack of staff who could diagnose malignancies and refer patients to specialists.16,20,21 Negative provider attitudes toward patients with cancer, cultural beliefs, taboos, and personal discomfort examining patients of the opposite sex also presented difficulties.22

Considering prior studies, our objective was to use the findings from this study to extend existing literature by including clinicians’ perspectives and national policies that link the identified barriers to potential policy actions, an approach not applied in previous studies.

METHODS

Study Design

Semistructured qualitative interviews of clinical oncologists and leaders of support and advocacy groups for patients with cancer were conducted via telephone and in person in Nairobi, Kenya, in January 2016. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical review board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Chapel Hill, NC) in May 2015 (institutional review board No. 13-4105) and the Africa Medical Research Ethics and Scientific Review Committee under study No. P199/2015 in November 2016.

The initial goal was to interview up to 20 key informants; it was anticipated this sample size would enable thematic saturation—the point at which no new themes would emerge from subsequent interviews. Study participants were recruited in two phases: first, through personal contact and introductions to key cancer sector experts and policymakers in Kenya, and second, using direct e-mails to organizations listed on the Kenya Cancer Network Organization Web site and in published articles. This purposive sampling was used to identify 45 potential participants by January 2016: 24 clinicians, 17 cancer support group leaders, and four policymakers.

Data Analysis and Interpretation of Interviews

The audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim. Qualitative analysis was conducted to identify and organize key themes emerging from the participants’ responses. Exemplar quotes from the interviews elaborated each theme. All data were reported anonymously to protect the identity of participants and their organizations. On the basis of the results of the qualitative interviews and prior literature, recommendations are made for improving access and delivery of services.

RESULTS

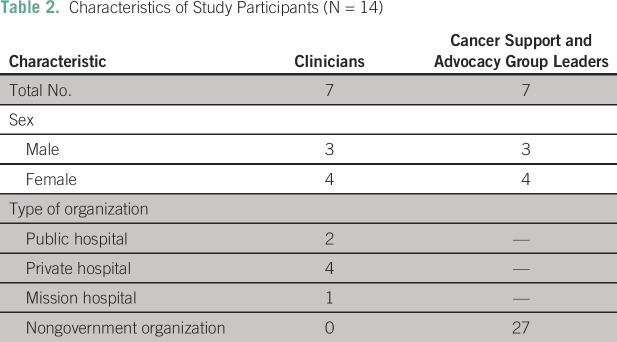

Between December 2015 and January 2016, 25 of the 45 contacted potential study participants responded. Nonrespondents were excluded from the study. Discussions with each of the respondents were used to explain the study and determine eligibility (clinician or leader of a support or advocacy group for patients with cancer or survivors). Of the 14 key informants who participated, eight were women, and six were men; seven were clinicians (three oncologists, two pathologists, one surgeon, and one palliative care physician), and seven were nonclinicians (cancer support and advocacy group leaders). Additional participant characteristics are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Study Participants (N = 14)

Thematic saturation was obtained by the 10th interview, but four additional interviews were conducted before analysis. One clinician’s responses were inaudible, so only 13 participants’ responses were analyzed.

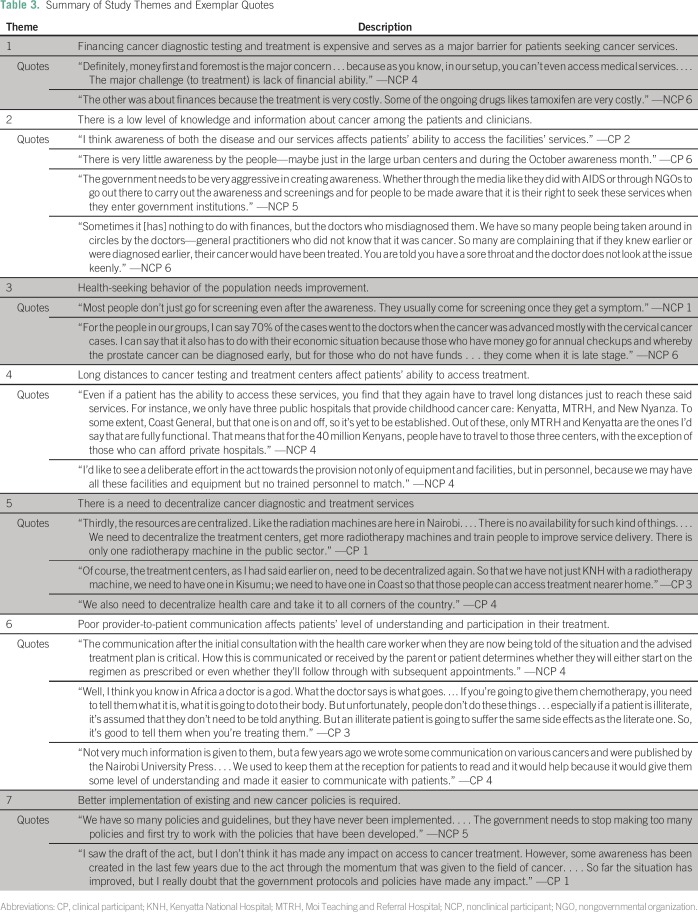

Study participants reported seven main barriers to patients seeking cancer testing and treatment regardless of the type of cancer: high cost of testing and treatment, low level of knowledge about cancer among the population and clinicians, poor health-seeking behaviors among the population, long distances to access services, lack of decentralized diagnostic and treatment facilities, poor provider-to-patient communication, and need for better cancer policy development and implementation. These barriers formed the themes that are described in this report and elaborated with exemplar quotes in Table 3. The type of respondent for each quote is noted as nonclinical participant (NCP; ie, cancer support or advocacy group leader) and clinical participant (CP; ie, clinician).

Table 3.

Summary of Study Themes and Exemplar Quotes

Financing Access to Cancer Testing and Treatment Is Costly

Most NCPs (n = 4) cited cancer screening and diagnostic costs as the leading barrier to timely testing and treatment.

“Definitely, money first and foremost is the major concern . . . because as you know, in our setup, you can’t even access medical services. . . . The major challenge [to treatment] is lack of financial ability.” —NCP 4

Some tests, such as mammograms, were deemed expensive for the average Kenyan. Respondents (n = 2) reported that some patients preferred to seek treatment in India, which they deemed cheaper and more effective than treatment in Kenya. The cost of transportation and accommodations in accessing oncology services in urban areas was cited as a barrier (n = 5), especially for rural populations.

Treatment at private facilities was cost prohibitive for most patients, resulting in the underuse of their radiotherapy machines. A subset of participants reported that the government had negotiated with some private hospitals to treat patients with urgent cancer cases, but the criteria for determining these cases was unclear.

Participants also cited the discriminatory practices of private insurance and the lack of clarity from the public insurance (NHIF) as barriers that patients must deal with. All 14 respondents were dissatisfied with the practices of insurance providers.

“Insurance companies are not really doing cancer. . . . If you get cancer, most of them don’t want to take it up because it’s really expensive. If you’re still under the cover, they may do the first course of treatment, then after that they start giving you letters that they can’t take it up.” —CP 3

“NHIF is covering cancer treatment, but they aren’t making noise about it. So most people don’t know they can go to NHIF to cover them or even cover their treatment abroad . . . NHIF [is] not disseminating information. And then there are those small clauses; you need to be 100% contributor; okay, who is that? Civil servants? Public servants? What does that really mean? There needs to be a whole education on that so that when you’re paying your NHIF, you know what it covers and what it doesn’t.” —NCP 3

Low Level of Knowledge and Information About Cancer

Respondents (n = 3) cited the need to increase national awareness about cancer. Others (n = 6) reported the lack of knowledge about cancer as a factor contributing to late presentation by patients. Providers’ lack of knowledge about cancer and its symptoms were a major cause of misdiagnosis cited by a subset of participants (n = 2).

“Sometimes it is nothing to do with finances, but the doctors who misdiagnosed them. We have so many people being taken around in circles by the doctors—general practitioners who did not know that it was cancer. So many are complaining that if they knew earlier or were diagnosed earlier, their cancer would have been treated. You are told you have a sore throat and the doctor does not look at the issue keenly.” —NCP 6

Health-Seeking Behavior of the Population

Late presentation is a major barrier to effective treatment. Study participants (n = 6) reported that most patients only sought medical care once symptoms were present.

“Most people don’t just go for screening even after the awareness. They usually come for screening once they get a symptom.” —NCP 1

A significant fear of cancer because of its association with death contributed to the late presentation.

“People will die but no one will say they died of cancer. They are very scared of the word and people want to hide it as a cause of death.” —NCP 2

In addition to fear, the financial cost associated with medical exams was reported as contributing to the low uptake of cancer screening and diagnostic tests (n = 2). However, most (n = 5) of the patient support and advocacy group leaders reported that they offered screening.

Long Distances to Cancer Testing and Treatment Centers

Participants (n = 5) reported that the current centralization of cancer diagnostic and treatment services in Nairobi posed a significant challenge outside of the city. The long distances affected patient compliance with treatment and follow-up with physicians.

“Even if a patient has the ability to access these services, you find that they again have to travel long distances just to reach these said services. For instance, we only have three public hospitals that provide childhood cancer care; Kenyatta, MTRH, and New Nyanza. . . . That means that for the 40 million Kenyans, people have to travel to those three centers except for those who can afford private hospitals.” —NCP 4

Need for Decentralization of Cancer Diagnostic and Treatment Services

It was thought that decentralization of cancer services was important, because it could prevent delays in accessing treatment.

“And as you’d expect, most of the facilities are here in Nairobi. … And that includes the doctors, as well. So, the rest of the country is really bare.” —NCP 3

Poor Provider-to-Patient Communication

Participants (n = 3) reported that the way physicians communicated with patients about their cancer was a determinant in whether patients sought treatment. They found this true regardless of the patient’s literacy level, especially when the disease was terminal.

“Well, I think you know in Africa a doctor is a god. What the doctor says is what goes. . . . If you’re going to give them chemotherapy, you need to tell them what it is, what it is going to do to their body. . . If a patient is illiterate, it’s assumed that they don’t need to be told anything. But an illiterate patient is going to suffer the same side effects as the literate one.” —CP 3

Better Cancer Policy Implementation Is Required

Participants cited the need for better implementation of cancer policies at the county and national levels.

“We have so many policies and guidelines, but they have never been implemented. . . . The government needs to stop making too many policies and first try to work with the policies that have been developed.” —NCP 5

Most agreed that the 2012 Cancer Act raised the level of awareness of the government about the rise in cancer.

“I saw the draft of the Act, but I don’t think it has made any impact on access to cancer treatment. However, some awareness has been created in the last few years due to the Act through the momentum that was given to the field of cancer. . . . So far, the situation has improved, but I really doubt that the government protocols and policies have made any impact.” —CP 1

Some cited the need for the Cancer Act to be revised to address costs, because cost was a major barrier and determinant of treatment.

“For the patients . . . if the policies are going to affect their lives . . . they want to know if the taxes on the cancer drugs like tamoxifen are going to be removed. The policies have to be felt by the patients, like reducing the tax on medication so that the prices can drop . . . like in India where the same drug can be half the price we get it here in Kenya. The policies are good but the government can do something like this (removing taxes on drugs) that can affect the people’s lives directly.” —NCP 6

DISCUSSION

This study extended prior literature by eliciting the perspectives of clinicians and cancer support and advocacy group leaders in Kenya regarding the barriers to diagnosis and treatment, as well as policy actions that can address the identified barriers. These key informant interviews identified affordable cancer testing and treatment services, lower drug costs, better equipped facilities and trained clinicians, proximity to testing and treatment centers, and favorable national cancer policies as critical to reducing barriers.

Findings indicate the cost of cancer testing and treatment is the biggest barrier facing Kenyans. Additionally, Kenya’s economic indicators point to its ability to address the financial barriers hindering the access of the population to cancer testing and treatment. With the highest gross domestic product (US$63,398 million) in the East Africa region, Kenya has the lowest health expenditure (only 3.5% of its gross domestic product) as compared with Tanzania (5.8%), Uganda (7.2%), and Rwanda (7.5%). Its health expenditure per capita (US$77) is also one of the lowest in the region, and life expectancy at birth is 62 years, compared with 65 years in Rwanda and Tanzania, and 59 years in Uganda.23

A key finding is that clinicians are aware that their services are out of reach for most self-paying and underinsured patients. Among insured patients, discriminatory practices by insurance companies, such as capping coverage and increasing premiums, lead to significant anxiety. In Kenya, like many other countries, primary health care facilities serve as the entry point for patients presenting with various symptoms. Providers at these facilities should be trained and equipped to screen patients, especially those with a family history of cancer or those with predisposing conditions, such as HIV/AIDS.9 Examples of effective interventions from neighboring countries include cervical cancer screening using skilled health workers in primary-, district-, provincial (county)-, and national-level hospitals in Uganda, Tanzania, Lesotho, and Zimbabwe. This includes colposcopies for referred cervical cancer cases in tertiary hospitals in Tanzania and Uganda.24 Inexpensive screening techniques for some of the cancers in Kenya can be applied by skilled health personnel and increase timely diagnosis for a majority of patients presenting with advanced disease.

Both clinicians and nonclinician informants reported a general lack of awareness about cancer and the need for public health education. Accurate information can lead to better awareness and help counter misinformation surrounding cancer.

The availability of one radiotherapy machine in the main public hospital (KNH) limits timely access to treatment of patients, whereas the underuse of cancer services in the private facilities is primarily tied to cost. The long wait times in public hospitals reduce the chances of better treatment outcomes and contribute to high cancer mortality rates.

In 2015, the Kenyan government and international stakeholders agreed to strengthen the capacity of KNH and MTRH and establish cancer centers in other counties—Kiambu, Mombasa, and Kisumu—as part of a phased approach to decentralizing cancer services. The government established public-private partnerships with some of Kenya’s private hospitals with underused capacity with the aim of easing the volume of patients with cancer at KNH. In addition to these efforts, Kenya can learn from Rwanda’s Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence, which has demonstrated how cancer care can be delivered in a resource-constrained setting.25 It can also learn from Rwanda’s public-private partnership, which includes the Dana-Farber Cancer Center and other donors,26 as it builds its public-private partnerships.

A number of limitations are acknowledged. This study recognizes the use of a limited subset of the population to provide opinions to inform recommendations. However, it is likely that the key informants are reliable sources of information about the impact of cost, infrastructure, and national health policies. Subsequent interviews with patients regarding their experiences in accessing diagnostic and treatment services for specific cancers would expand on certain themes identified in this study.

In conclusion, effective cancer testing and treatment options can be developed in resource-constrained environments like Kenya, where the technical expertise required to administer treatment modalities is underdeveloped. Implementing recommendations based on this study could improve Kenyans’ timely access to cancer testing and treatment. A review of effective cancer interventions and policies implemented in countries facing challenges similar to those faced by Kenya would provide lessons to Kenya’s health sector and policymakers.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Cancer Outcomes Research Program, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, which awarded a travel grant to facilitate interviewing of study participants.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Louise K. Makau-Barasa, Sandra B. Greene, Asheley Skinner, Antonia V. Bennett

Collection and assembly of data: Louise K. Makau-Barasa

Data analysis and interpretation: Louise K. Makau-Barasa, Sandra B. Greene, Nicholas A. Othieno-Abinya, Stephanie Wheeler, Antonia V. Bennett

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

–Louise K. Makau-Barasa

No relationship to disclose

Sandra B. Greene

No relationship to disclose

Nicholas A. Othieno-Abinya

No relationship to disclose

Stephanie Wheeler

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Asheley Skinner

No relationship to disclose

Antonia V. Bennett

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx WHO International Agency for Cancer Research: GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012.

- 2. http://www.ipcrc.net/pdfs/Kenya-National-Cancer-Control-strategy.pdf Kenyan Ministry of Public Health, Kenyan Ministry of Medical Services: National Cancer Control Strategy 2011-2016.

- 3. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_population.aspx WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer: GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012: Population fact sheets—World.

- 4. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_population.aspx?country=404 WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer: GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012: Population fact sheets—Kenya.

- 5. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94384/1/9789241506236_eng.pdf?ua=1 WHO: Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases 2013-2020: Action Plan.

- 6. http://www.who.int/cancer/country-profiles/ken_en.pdf?ua=1 WHO: Cancer Country Profiles, 2014: Kenya.

- 7. http://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/160_KenyadevolutionandhealthmeetingreporFINAL.pdf Kenyan Ministry of Medical Services, Kenyan Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation: Devolution and Health in Kenya: Consultative Meeting Report.

- 8. http://kenyalaw.org/kl/fileadmin/pdfdownloads/bills/2015/CancerPreventionandControl_Amendment_Bill2015.pdf Government of Kenya: Cancer Prevention and Control (Amendment) Bill, 2015.

- 9. http://kehpca.org/wp-content/uploads/National-Cancer-Treatment-Guidelines2.pdf Kenyan Ministry of Health: National Guidelines for Cancer Management Kenya.

- 10.National Health Insurance Fund http://www.nhif.or.ke/healthinsurance/outpatientServices : Outpatient Services.

- 11. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-528. Mutebi M, Wasike R, Mushtaq A, et al: The effectiveness of an abbreviated training program for health workers in breast cancer awareness: Innovative strategies for resource constrained environments. http://ecommons.aku.edu/eastafrica_fhs_mc_gen_surg/15/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Njuguna F, Mostert S, Slot A, et al. : Abandonment of childhood cancer treatment in Western Kenya. Arch Dis Child 99:609-614, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Brien M, Mwangi-Powell F, Adewole I. F., et al. : Improving access to analgesic drugs for patients with cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol 14:e176-e182, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0843-y. Rosser J.I, Njoroge B, Huchko MJ: Cervical cancer stigma in rural Kenya: What does HIV have to do with it? J Cancer Educ 31:413-418, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Njuguna F, Mostert S, Seijffert A, et al. : Parental experiences of childhood cancer treatment in Kenya. Support Care Cancer 23:1251-1259, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kisuya J, Wachira J, Busakhala N, et al. : Impact of an educational intervention on breast cancer knowledge in western Kenya. Health Educ Res 30:786-796, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-201404. Sayed S, Moloo Z, Bird P, et al: Breast cancer diagnosis in a resource poor environment through a collaborative multidisciplinary approach: The Kenyan experience. J Clin Pathol 66:307-311, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-559. Kivuti-Bitok LW, McDonnell G, Pokhariyal GP, et al: Self-reported use of Internet by cervical cancer clients in two national referral hospitals in Kenya. BMC Res Notes 5:559, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Were E, Nyaberi Z, Buziba N: Perceptions of risk and barriers to cervical cancer screening at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH), Eldoret, Kenya. Afr Health Sci 11:58-64, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huchko MJ, Sneden J, Sawaya G, et al. : Accuracy of visual inspection with acetic acid to detect cervical cancer precursors among HIV-infected women in Kenya. Int J Cancer 136:392-398, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ngugi CW, Boga H, Muigai AW, et al. : Factors affecting uptake of cervical cancer early detection measures among women in Thika, Kenya. Health Care Women Int 33:595-613, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.01.015. Agurto I, Arrossi S, White S, et al: Involving the community in cervical cancer prevention programs. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 89:S38-S45, 2005 (suppl 2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SH.XPD.OOPC.ZS&country=KEN The World Bank: Data Bank: World Development Indicators: Kenya.

- 24.Chirenje ZM, Rusakaniko S, Kirumbi L, et al. : Situation analysis for cervical cancer diagnosis and treatment in east, central and southern African countries. Bull World Health Organ 79:127-132, 2001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tapela NM, Mpunga T, Hedt-Gauthier B, et al. : Pursuing equity in cancer care: implementation, challenges and preliminary findings of a public cancer referral center in rural Rwanda. BMC Cancer 16:237, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Health Partnerships Directory : Oncology Training in Rwanda. http://partnerships.ifpma.org/partnership/oncology-training-in-rwanda