Abstract

Purpose

Despite increased access to palliative care in Africa, there remains substantial unmet need. We examined the impact of approaches to promoting the development of palliative care in two African countries, Uganda and Kenya, and considered how these and other strategies could be applied more broadly.

Methods

This study reviews published data on development approaches to palliative care in Uganda and Kenya across five domains: education and training, access to opioids, public and professional attitudes, integration into national health systems, and research. These countries were chosen because they are African leaders in palliative care, in which successful approaches to palliative care development have been used.

Results

Both countries have implemented strategies across all five domains to develop palliative care. In both countries, successes in these endeavors seem to be related to efforts to integrate palliative care into the national health system and educational curricula, the training of health care providers in opioid treatment, and the inclusion of community providers in palliative care planning and implementation. Research in palliative care is the least well-developed domain in both countries.

Conclusion

A multidimensional approach to development of palliative care across all domains, with concerted action at the policy, provider, and community level, can improve access to palliative care in African countries.

INTRODUCTION

Despite considerable recent growth in palliative care services in Africa, they remain accessible to less than an estimated 5% of those in need.1 With cancer rates expected to rise 400% by 2050,2 the need for palliative care services on the continent will continue to outstrip capacity3 unless effective strategies to promote their development are given the highest priority for implementation. Although comparisons have been made between palliative care in high-income and lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs),4 comparisons between countries with socioeconomic and geographic similarities may identify effective regional strategies for developing palliative care.

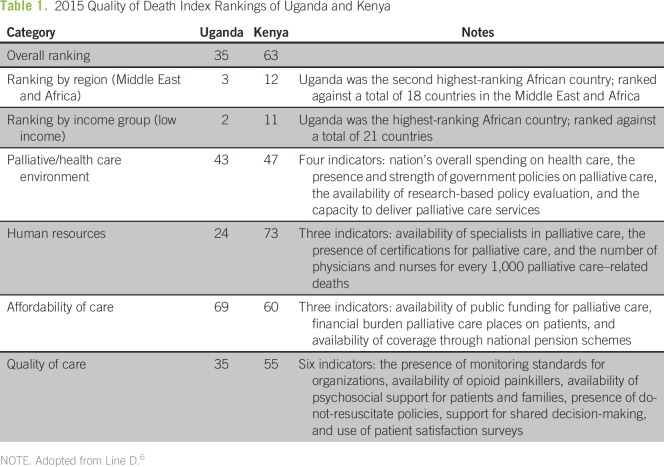

Kenya and Uganda have both been identified as leaders in palliative care development in Africa.5 Differences in strategies in each country may account for disparities in their ratings on the 2015 Quality of Death (QOD) Index, developed by the Intelligence Unit of The Economist newspaper to rank 80 countries in terms of the quality and availability of palliative care services for adult populations (Table 1).6 Uganda ranked thirty-fifth overall, and Kenya ranked sixty-third.6

Table 1.

2015 Quality of Death Index Rankings of Uganda and Kenya

Palliative care development has been considered across five broad domains: education and training of health care providers in palliative care, access to opioid medications, professional and public attitudes toward palliative care, integration of palliative care into national health care systems, and palliative care research.7 These domains of development are consistent with the WHO Public Health Model for palliative care development.8 Consistent with a review of barriers to palliative care development in LMICs,7 we have added domains of research9 and public and professional attitudes toward palliative care.

This review examines and compares strategies used to promote the development of palliative care in Uganda and Kenya in relation to these five domains, with a view toward identifying successes that can be used in other African countries that are at a similar developmental stage with regard to palliative care and elsewhere.

METHODS

This review examined published literature on palliative care development in Uganda and Kenya, with an emphasis on publications from 2010 and later. Specifically, a literature search of MEDLINE and Africa-wide databases was performed on June 3, 2016, using the following search terms: “palliative care” or “palliative medicine” or “hospice” or “end-of-life care” and “Kenya” or “Uganda” or “Sub-Saharan Africa.” Reference lists of applicable articles were reviewed to source additional studies of interest. A literature search was also conducted on Google and Google Scholar by using search terms similar to those listed above. The Web sites of the WHO, the African Palliative Care Association (APCA), Kenyan Hospice and Palliative Care Association (KEHPCA), Palliative Care Association of Uganda (PCAU), Hospice Africa Uganda (HAU), and the respective Ministry of Health (MOH) Web sites of Kenya and Uganda were also examined for relevant literature, with restriction to the publications sections of the Web sites.

We considered using the 2015 QOD Index, which provides a global ranking system with regard to palliative and end-of-life care. However, our aim was not to examine the overall quality of palliative care in these countries, but development of palliative and end-of-life care in specific actionable areas that could lead to practical recommendations. Although these five practicable domains were used to structure our review, we also relate these to corresponding categories of the QOD index, as appropriate.

RESULTS

Palliative Care Education and Training

Education and training in palliative care are significant facilitators in its development.7 Palliative care education and training are best represented on the QOD Index by the human resource category.6 This category includes the availability of palliative care specialists and practitioners, the presence of certification for palliative care, and the number of physicians and nurses for every 1,000 palliative care–related deaths (Table 1).6 In this category, Uganda ranked twenty-fourth overall, making it the highest-ranking African country, and Kenya ranked seventy-third, making it the second lowest-ranking African country.6

HAU, the nongovernmental organization that first brought palliative care to Uganda in 1993,10 has trained more than 8,000 nurses and physicians in palliative care,11 as well as extending its education programs to medical officers, community volunteer workers, spiritual caregivers, traditional healers, and allied health professionals.12 Furthermore, in collaboration with Makerere University, HAU created a training program for nurses and clinical officers to provide the necessary skills to prescribe opioids for pain management.7 This program has helped decrease the gap in the availability of medical professionals trained to prescribe opioids.

The widespread integration of palliative care into the educational curricula of health care professionals (HCPs) in Uganda has facilitated its application into mainstream health care.13,14 This includes a national palliative care training manual recently developed by the Ugandan MOH for health care providers at all levels of service delivery.15 Challenges in education that remain include a shortage of trained palliative care providers16 and the need for formal recognition of specialized palliative care training.9 Overall, however, education and training seem to have contributed significantly to the relatively high ranking of Uganda in the human resource category of the QOD Index.

Although Kenya scored significantly lower than Uganda in the QOD Index’s human resource category,6 its notable successes in palliative care education and training include the integration of palliative care into the educational curricula of HCPs, with mandatory palliative care courses for medical students and the inclusion of 35 hours of palliative care education in the nursing curriculum.17 The Diana Princess of Wales Memorial Fund provided mentorship and funding to integrate palliative care into these curricula.18 There has also been an increasing focus on postgraduate palliative care training for HCPs in Kenya, as demonstrated by the National Palliative Care Training Curriculum for HIV/AIDS, Cancer and Other Life-Threatening Illness.19

There is also evidence in Kenya of increasing efforts by national palliative care organizations and by national and international training institutions to implement palliative care education and training. For example, in collaboration with Oxford Brookes University in the United Kingdom, Nairobi Hospice offers a postgraduate course in palliative care.18,20 This course is designed to educate health care providers in symptom management, bereavement care, and other issues relating to palliative care provision.21 The importance of palliative care education and training among nurses has also been recognized in Kenya.22 For example, since 2009, the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium program has provided palliative care training to nurse educators who subsequently return to their home institutions to train local nurses in palliative care.23 In addition, the Kenya Medical Training College recently launched an 18-month higher education distance-learning course in palliative care for health care workers.24

Despite these efforts to improve palliative care education and training, there remain insufficient numbers of trained palliative care providers in Kenya.23 This deficit may be the result of a lack of funding for specialist palliative care,24 a low HCP-to-patient ratio,23 and organizational constraints related to insufficient numbers of qualified instructors.25 To address this shortfall, active efforts are being made to promote palliative care development at the national level, and its ranking in this area therefore seems likely to improve.

Opioid Availability

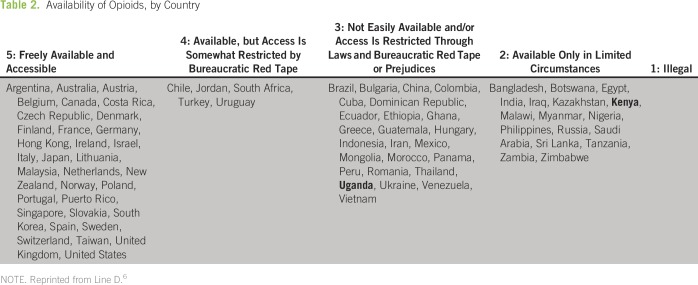

Improving access to pain-relieving medications, particularly opioids, is essential for the optimal delivery of palliative care.26 Opioid availability is directly related to the quality of palliative care, accounting for 30% of the quality-of-care category in the QOD Index (Table 1). Uganda ranked thirty-fifth in this category, the second highest African country, whereas Kenya ranked fifty-fifth.6 In another QOD Index ranking that categorized countries solely on availability of opioid painkillers (Table 2), Uganda was placed in category 3, in which opioids are “not easily available and/or access is restricted through laws and bureaucratic red tape or prejudices,” and Kenya was in category 2, in which opioids are “only available in limited circumstances.”6

Table 2.

Availability of Opioids, by Country

Uganda’s success in improving access to opioids has been facilitated by long-standing public-private partnerships between Uganda’s MOH with both HAU and PCAU.6 These partnerships, and advocacy by HAU and PCAU contributed to the registration of oral morphine as a palliative treatment by the National Drug Authority.16,27 The Ugandan government also allocated specific funding for the purchase of morphine,6 established it as an essential medication,15 and made it available at no cost for patients in need of pain control.28 In addition, oral morphine is now locally reconstituted and distributed through a collaborative partnership between the Ugandan government and HAU.29

Perhaps as important as opioid availability is broadening the range of opioid prescribers. This was achieved in 2004 with the support of an MOH statute (MOH Statutory Instrument 2004 No. 24).30 This statute permits nurses and clinical officers who have undergone specialized training to prescribe oral morphine legally for pain management.20 Efforts to regulate opioids in Uganda have also been supported by Guidelines for Handling of Class A Drugs, which includes a comprehensive strategy for the safe use of oral morphine.31 Importantly, this increased access to therapeutic opioids in Uganda occurred without demonstrable evidence of their illicit diversion.3

Through strong partnerships and persistent advocacy,3 Uganda has secured financing for opioids, expanded opioid prescribing power to additional HCPs, relaxed restrictive opioid regulations, and placed safe, accessible, and affordable pain-relief at the forefront of palliative care. Remaining challenges include the need for more trained prescribers,22 negative attitudes and stigma surrounding opioid use (and palliative care in general),3 and the organizational capacity needed to acquire, store, and distribute morphine.3,16 Particularly important is the need to improve supply chain management to avoid delays within the system that regularly lead to shortages and stock-outs at health facilities29 (in 2013, only 50% of facilities in Uganda had minimum stock levels of morphine).32 Despite these challenges, Uganda’s success in improving the accessibility of opioids is an effective model that may be applied in other African countries.

Kenya has also made a number of advances in expanding access to pain-relieving medications. The Kenyan government responded to advocacy by accepting the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs33 and adopting the WHO List of Essential Medicines, which includes 14 palliative care medications, including morphine and codeine.33 More recently, significant strides were made in advancing pain control through the creation of Kenya’s National Palliative Care Guidelines.19 These guidelines were created by the MOH in collaboration with KEHPCA and include recommendations for the safe use of opioids for pain management.19 In 2013, the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority arranged a central supply of morphine for public hospitals and removed its tax on morphine powder.17

As a result of the collective effort to increase opioid availability for palliative care, morphine consumption increased more than three-fold in Kenya between 2010 and 2014.17 However, despite this increase, opioids are still largely unavailable at public health facilities,31 are unaffordable as a result of restrictive regulations that limit supply,33 and are associated with persistent negative attitudes and fear among HCPs about opioid prescribing.33

Attitudes Toward Palliative Care

Cultural attitudes and behavior are significant barriers to the development and implementation of palliative care in Africa.7 This domain is encompassed in the community engagement category of the QOD Index, which includes public awareness of palliative care and availability of community volunteer workers for palliative care.6 In this category, Uganda ranked fifteenth, making it the highest-ranking African country, and Kenya ranked forty-fifth.5

Increasing exposure to palliative care in the community may help diminish stigma and reshape attitudes toward palliative care. A specific feature of Uganda’s success has been the employment of community volunteer workers who advocate for palliative care in the community and help to destigmatize death and dying.7,34 These community volunteer workers integrate into communities and gain the trust of patients and their families by providing culturally sensitive care that respects patients’ values regarding dying and death and thereby increases the willingness of communities to use palliative care services.34 These volunteers have helped deliver palliative care that respects patients’ end-of-life wishes, including their preference to die at home.10,16 In addition to volunteers, the home-based model of palliative care delivery in Uganda through HAU27,35 is supported by a homecare package that includes access to pain-relieving medications.36 Furthermore, mainstream media, including television and radio broadcasts and monthly newsletters, has also been used in Uganda to raise awareness of palliative care, encourage openness about dying and death, and sensitize the public to palliative and end-of-life care.6,37 One of the ongoing challenges in Uganda is the negative attitudes of some HCPs toward palliative care,22 including the belief that it accelerates death 22,38 and is a secondary line of care.12

Although Kenya performed worse than Uganda in the community engagement category of the QOD Index, efforts are underway to shift attitudes toward palliative care6 and empower communities in the provision of palliative care services.39 This is necessary for palliative care to become more broadly available and not for just a few who are aware.24 Similar to the Ugandan model, KEHPCA is also using local television, radio, print media, and public events to communicate impactful messages about and generate awareness of palliative care.39 Establishing partnerships with legal and paralegal organizations is another strategy that Kenya is using to encourage patients to recognize their rights to palliative care services.39 Finally, Kenya has recently created a National Patients’ Rights Charter, which acknowledges pain relief and palliative care as a basic human right for all Kenyans.39

Although some strides have been made, there is an urgent need in Kenya to provide culturally appropriate home-based care 24,39 and improve the use of palliative care services. Despite the preference for home-based care,40 current palliative care is mostly delivered by hospitals and hospices that are difficult for many people to access.24,39

Integration of Palliative Care Into National Health Systems

The integration of palliative care into mainstream health service provision and national health policies has been recognized both in Africa and internationally as an essential foundation for palliative care development.13,41 This domain is best represented by the palliative and health care environment category of the QOD Index, which is based on the presence and strength of government policies on palliative care (Table 1).6 Both countries performed relatively well in this category, with Uganda ranking forty-third and Kenya ranking forty-seventh. Furthermore, a recent study commissioned by the Open Society Foundation International Palliative Care Initiative, which ranked countries on the basis of the level of integration of palliative care into mainstream health care, placed both Kenya and Uganda in the highest category when measured against all other countries globally. This category, which refers to integration of palliative care services,5 is subdivided into preliminary and advanced levels of integration. Uganda was ranked in the advanced and Kenya in the preliminary category.5 Notably, Uganda was one of only 20 countries worldwide that ranked in the advanced integration category and the only LMIC to rank in this category.5

Advocacy and leadership have played an essential role in achieving the integration of palliative care into Uganda’s national health system and policies. Consistent advocacy over a 5-year period mobilized support for a unifying workshop on palliative care in Uganda in 1998.42 At this workshop, initial targets for palliative care development were identified, local champions were chosen to reach these targets,31 and the Task Force on Palliative Care and Pain Relief in Cancer and HIV/AIDS was formed which included representatives from the MOH, national stakeholders, and the WHO.16,42 Continued advocacy, governmental collaboration, and lobbying eventually led to palliative care being recognized as an essential service in the Ugandan National Health Policy Plan and Strategy.2 These advocacy efforts have been supported by a number of national and global associations, including HAU, PCAU, and APCA.2

Embedding palliative care within Uganda’s health care policies and budgets has been an important step in the integration of palliative care into mainstream service provision. A substantial achievement in this regard was the inclusion of palliative care in the MOH 5-Year Strategic Health Plan (2001-2005), which prioritized palliative care as an essential clinical service and provided a strategy for its implementation.3,27 Subsequent National Strategic Health Plans fully incorporate palliative care, emphasizing palliative care service provision, opioid availability, integration into educational curricula, and strengthening referral systems.42 Palliative care was also integrated into Uganda’s HIV/AIDS National Strategic Framework42 and is currently included in the national health care budgeting process.43 As of 2015, Uganda’s MOH created a National Palliative Care Policy, which provides a framework for the national scale-up and implementation of palliative care services.29 Specifically, this policy outlines 11 priority areas for development, including availability of services and essential medications, education and training, community participation, and research and integration. It also delineates an objective for each area and outlines strategies to achieve the specified objectives.29

Uganda’s longstanding commitment to advocacy, governmental collaboration, and the establishment of partnerships has contributed to its success in integrating palliative care into mainstream health care. The current lack of national guidelines on palliative care or sufficient budgetary allocation for palliative care services continues to limit their widespread integration.29 Nevertheless, Uganda serves as a valuable model for advancing the integration of palliative care into mainstream health care, which can be applied to improve palliative care integration in other LMICs.

The improved integration of palliative care into the health care system in Kenya may be partly attributed to political will and the establishment of collaborative partnerships. Until 2010, palliative care provision in Kenya was mainly supported by nongovernmental organizations and managed by independent hospices and mission hospitals.19 However, at that time, Kenya’s Director of Medical Services mandated that 10 public hospitals integrate palliative care into service provision.19 A public-private partnership between KEHPCA and Kenya’s MOH played a significant role in this palliative care service expansion, with the Diana Princess of Wales Memorial Fund and the True Colors Trust financially supporting the project.44

Through the collaborative efforts of KEHPCA and the country’s MOH, palliative care is embedded in existing national strategies and guidelines. Particularly important was the creation of Kenya’s National Palliative Care Guidelines in 2013, which aimed to improve the integration of palliative care into health care provision.19 In that same year, the National Palliative Care Training Curriculum for HIV/AIDS, Cancer, and other Life-Threatening Illnesses was created, serving as a guide for HCP training in palliative care.45 There is also increased emphasis on embedding palliative care into national documents, including the National Cancer Control Strategy (2011-2016),46 National Guidelines for Cancer Management Kenya (2013),24 Kenya’s National Patients’ Rights Charter (2013),17 Kenya’s National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (2015-2020),24 and the Community Health Volunteers Non-Communicable Diseases Training Manual.39 Collectively, these documents have enabled health facilities and HCPs throughout Kenya to provide increasingly integrated palliative care services on the basis of nationally mandated standards.

The political will of Kenya’s government to integrate palliative care into mainstream health care has dramatically impacted palliative care delivery. These efforts, and the inclusion of palliative care into numerous national documents, demonstrate that palliative care is increasingly being recognized as an integral component of comprehensive care in Kenya. Palliative care integration might be advanced further in the country by a specific palliative care policy,39 the inclusion of palliative care in national health budgets,39 and in the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and programs.17 These improvements could lead to significant advancements in the integration of palliative care into mainstream health care and in the provision of palliative care throughout Kenya.

Palliative Care Research

Evidence-based medicine is an underpinning of high-quality end-of-life care,7 and research has been proposed as an essential component of palliative care development.7,9 There has been a substantial increase in the number of peer-reviewed publications in palliative care from both Kenya and Uganda,47 and these two countries are increasingly recognized as African leaders in palliative care research.48 The QOD Index has no category that assesses palliative care research.

A growing research base for palliative care in Uganda and Kenya has been supported by the establishment of international collaborations to increase the critical research mass in Africa.49 This includes the African Palliative Care Research Network, which was established in 2011 to develop a palliative care evidence base specific to the African setting and to connect African and international researchers.48,50 In addition, Uganda established its own national research network, the Makerere Palliative Care Unit Research Network, which engages HCPs in collaborative research and knowledge exchange.51 Although Kenya does not have its own national research network, partnerships have developed in recent years between international research groups and local researchers at the University of Nairobi, with support from both KEHPCA and APCA.47 The hosting of biennial national palliative care conferences by PCAU and KEHPCA51 has also promoted collaboration and knowledge exchange among palliative care researchers and clinicians. These conferences have created a supportive environment for researchers and a forum to disseminate evidence-based findings.51

Although progress is being made in both Uganda and Kenya, these countries face a number of common barriers to palliative care research, including the inadequate number of permanent funded national research groups,47 the lack of indigenous trained palliative care researchers,49 and scant career opportunities in palliative care research in both countries.47 Furthermore, much valuable evidence is being lost because of poor documentation practices.2 Despite these challenges, both Uganda and Kenya are working toward a model of palliative care that is rooted in a strong evidence base.

DISCUSSION

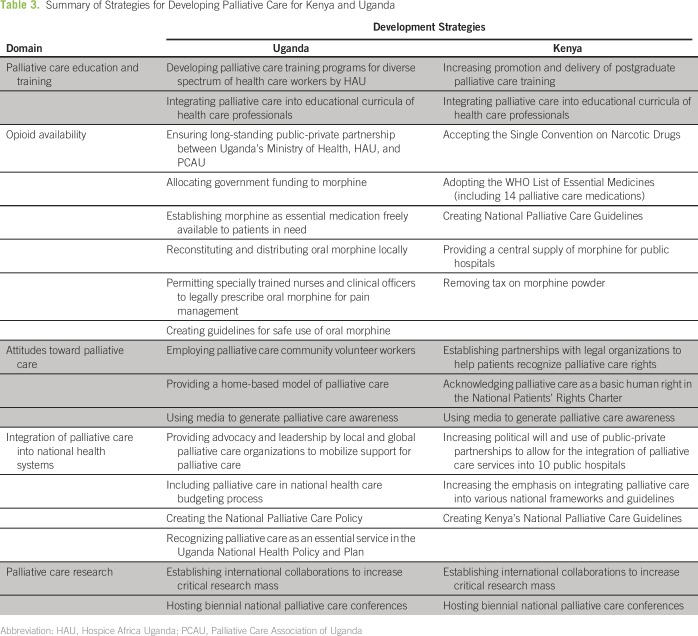

The strategies that Uganda and Kenya use to develop palliative care provide valuable lessons for the development of palliative care in other settings (Table 3). Each of the domains of palliative care development are independently important and mutually reinforcing. Furthermore, the development of palliative care is dependent on change at the levels of policy, health care provision, and the community.

Table 3.

Summary of Strategies for Developing Palliative Care for Kenya and Uganda

At a policy level, the integration of palliative care into national health systems is essential for its universal provision. Efforts to improve integration should embrace the trusted and widely available traditional and complementary approaches to palliative care. Because pain relief and symptom control are cornerstones of palliative care, regulatory policies to govern safe opioid provision are also an essential foundation for palliative care development. Such policies provide health care administrators and providers with a national framework for the acquisition, storage, and distribution of opioids and demonstrate governmental support for the provision of therapeutic opioids. Such measures help to dispel irrational or exaggerated fears and concerns surrounding the use of opioids for pain relief. Finally, it is essential for policy makers to include palliative care professional and advocacy bodies in the governmental decision-making process.

There are a number of factors at the level of health care service delivery and clinical practice that are also necessary for widespread palliative care development. These include educating and training of a broad range of mainstream health care providers, alternative and traditional healers, community volunteers, and providers of psychosocial and spiritual support. Culturally sensitive communication strategies are also needed to facilitate discussions about death and dying and advanced care planning. Efforts should also be made to facilitate the provision of end-of-life care at home, in hospice, and in hospital.

In conclusion, public awareness of and acceptance of the need for palliative care is essential for the use and uptake of palliative care services. Both policymakers and health care providers have a role in ensuring that the general public is educated about palliative care, and that palliative care services are available and implemented in a timely fashion. Such education will help to combat the stigma of life-limiting and life-threatening conditions. Strategic interventions are needed at the levels of policy, clinical care, and the community to promote development in all domains of palliative care. Research is currently the most neglected domain, and efforts are needed to ensure that it is developed in tandem with the development of clinical palliative care services.

Footnotes

Supported by the Global Institute of Psychosocial, Palliative and End-of-Life Care, University of Toronto, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Brooke A. Fraser, Gary Rodin

Collection and assembly of data: Brooke A. Fraser

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Brooke A. Fraser

No relationship to disclose

Richard A. Powell

No relationship to disclose

Faith N. Mwangi-Powell

No relationship to disclose

Eve Namisango

No relationship to disclose

Breffni Hannon

No relationship to disclose

Camilla Zimmermann

No relationship to disclose

Gary Rodin

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Downing J, Grant L, Leng M, et al. : Understanding models of palliative care delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: Learning from programs in Kenya and Malawi. J Pain Symptom Manage 50:362-370, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding R, Higginson IJ: Palliative care in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 365:1971-1977, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Logie DE, Harding R: An evaluation of a morphine public health programme for cancer and AIDS pain relief in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health 5:82, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Souza JA, Hunt B, Asirwa FC, et al. : Global healthy equity: Cancer care outcome disparities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. J Clin Oncol 34:6-13, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynch T, Connor S, Clark D: Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global update. J Pain Symptom Manage 45:1094-1106, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Line D (ed): The 2015 Quality of Death Index: Ranking palliative care across the world. The Economist, Intelligence Unit, 2015. https://www.eiuperspectives.economist.com/healthcare/2015-quality-death-index.

- 7.Hannon B, Zimmermann C, Knaul FM, et al. : Provision of palliative care in low- and middle-income countries: Overcoming obstacles for effective treatment delivery. J Clin Oncol 34:62-68, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stjernswärd J, Foley KM, Ferris FD: The public health strategy for palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 33:486-493, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harding R, Selman L, Powell RA, et al. : Research into palliative care in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol 14:e183-e188, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kikule E: A good death in Uganda: Survey of needs for palliative care for terminally ill people in urban areas. BMJ 327:192-194, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harris P: Cross-cultural palliative care. Nurs Times 109:25, 2013. [PubMed]

- 12. Bongiovanni A, Greenan MA: Hospice Africa Uganda: End-of-project evaluation of palliative care services. Final Report. New York: Population Council. 2009. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pdacr191.pdf.

- 13. African Palliative Care Association: Strategic Plan 2011-2020. https://www.africanpalliativecare.org/images/stories/pdf/apca_sp.pdf.

- 14.African Palliative Care Association : Standards for providing quality palliative care across Africa. https://www.africanpalliativecare.org/images/stories/pdf/APCA_Standards.pdf

- 15.Opendi SA: Uganda: Ministerial statement on palliative care. http://www.ehospice.com/africa/Default/tabid/10701/ArticleId/6382

- 16.Nabudere H, Obuku E, Lamorde M: Advancing the integration of palliative care in the national health system. http://www.academia.edu/19225311/Advancing_the_Integration_of_Palliative_Care_in_the_National_Health_System [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lohman D, Amon JJ: Evaluating a human rights-based advocacy approach to expanding access to pain medicines and palliative care: Global advocacy and case studies from India, Kenya, and Ukraine. Health Hum Rights 17:149-165, 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawlinson F, Gwyther L, Kiyange F, et al. : The current situation in education and training of health-care professionals across Africa to optimise the delivery of palliative care for cancer patients. Ecancermedicalscience 8:492, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health : National palliative care guidelines. http://kehpca.org/wp-content/uploads/National-Palliative-Care-Guidelines-02.10.pdf

- 20.Clark D, Wright M, Hunt J, et al. : Hospice and palliative care development in Africa: A multi-method review of services and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 33:698-710, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nairobi Hospice : Diploma in higher education in palliative care DipHE a franchise with Nairobi Hospice. http://nairobihospice.or.ke/?page_id=12384

- 22.Merriman A: Uganda: Current status of palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 24:252-256, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malloy P, Paice JA, Ferrell BR, et al. : Advancing palliative care in Kenya. Cancer Nurs 34:E10-E13, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenya Hospices and Palliative Care Association : Annual Report, 2014. http://kehpca.org/wp-content/uploads/Annual-Report-2014_draft.pdf

- 25. African Palliative Care Association and Kenya Hospices and Palliative Care Association: Palliative Care: An Essential Part of Medical and Nursing Training. 2011. http://kehpca.org/wp-content/uploads/education%20conference.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merriman A, Harding R: Pain control in the African context: The Ugandan introduction of affordable morphine to relieve suffering at the end of life. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 5:10, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagwe JG, Barnard D: The introduction of palliative care in Uganda. J Palliat Med 5:160-163, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsay S: Leading the way in African home-based palliative care: Free oral morphine has allowed expansion of model home-based palliative care in Uganda. Lancet 362:1812-1813, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Republic of Uganda Ministry of Health : National palliative care policy. Uganda: 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Muhwezi BJ: Statutory instruments 2004 no. 4, national drug authority regulations. The Republic of Uganda Ministry of Health, 2004. https://www.google.ca/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0ahUKEwj8xvb08rrUAhUB24MKHajhASIQFggkMAA&url=https%3A%2F%2Fhingx.org%2FShare%2FAttachment%2F758%3FfileName%3Duganda%2520prescription%2520supply%2520of%2520narcotic%2520analgesics%2520mulumba-recd-august17-12.pdf&usg=AFQjCNE7dghSIpUH8zt0w-MNhA824AMbdw&sig2=DpGCGqfoIpC4O92w1yjBpw.

- 31.Stjernswärd J: Uganda: Initiating a government public health approach to pain relief and palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 24:257-264, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harding R, Simms V, Penfold S, et al. : Availability of essential drugs for managing HIV-related pain and symptoms within 120 PEPFAR-funded health facilities in East Africa: A cross-sectional survey with onsite verification. Palliat Med 28:293-301, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kenya Hospices and Palliative Care Association : Legal aspects in palliative care: Handbook http://kehpca.org/wp-content/uploads/Legal-Aspects-in-PC-Handbook_Final-Feb-2014.pdf

- 34.Grant L, Brown J, Leng M, et al. : Palliative care making a difference in rural Uganda, Kenya and Malawi: Three rapid evaluation field studies. BMC Palliat Care 10:8, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall-Lucette S, Corbett K, Lartey N, et al. : Developing locally based research capacity in Uganda. Int Nurs Rev 54:227-233, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization : Cancer control: Knowledge into action—WHO guide for effective programmes. http://www.who.int/cancer/modules/en/

- 37.Freeman P: A visit to hospice Africa. J Public Health Policy 28:62-70, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Downing J: Palliative care and education in Uganda. Int J Palliat Nurs 12:358-361, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ali ZV: Putting the ‘public’ into public health: Innovative partnerships in palliative and end of life care: The Kenya experience. Prog Palliat Care 24:4-5, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Downing J, Gomes B, Gikaara N, et al. : Public preferences and priorities for end-of-life care in Kenya: A population-based street survey. BMC Palliat Care 13:4, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance: Civil society report: Update on implementation of the 2014 World Health Assembly resolution on palliative care. 2016. http://www.thewhpca.org/resources/item/civil-society-report-update-on-implementation-of-the-2014-wha-resolution-on-palliative-care.

- 42.Jagwe J, Merriman A: Uganda: Delivering analgesia in rural Africa—Opioid availability and nurse prescribing. J Pain Symptom Manage 33:547-551, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. World Health Organization: Cancer: A community health approach to palliative care for HIV/AIDS and cancer patients in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2004. http://www.who.int/cancer/publications/community_health_approach/en/

- 44. [No author listed]: Kenyan hospitals introducing palliative care. Science Africa 18:1-2, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health : National palliative care training curriculum for HIV & AIDS, cancer and other life threatening illnesses: Trainees manual. http://kehpca.org/wp-content/uploads/Nationa-Palliative-Care-Training-Curriculum_Trainees-Manual.pdf

- 46. Mwangi-Powell FN, Downing J, Powell RA, et al: Palliative care in Africa, in Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice J (ed): Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing (ed 4). New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Namisango E, Powell RA, Kariuki H, et al. : Palliative care research in eastern Africa. Eur J Palliat Care 20:300-304, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Powell RA, Harding R, Namisango E, et al. : Palliative care research in Africa: An overview. Eur J Palliat Care 20:162-167, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Powell RA, Harding R, Namisango E, et al. : Palliative care research in Africa: Consensus building for a prioritized agenda. J Pain Symptom Manage 47:315-324, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance : Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. http://www.who.int/nmh/Global_Atlas_of_Palliative_Care.pdf

- 51.Namisango E, Kiyange F, Luyirika EB: Possible directions for palliative care research in Africa. Palliat Med 30:517-519, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]