Patients with cancer in developing and low-income countries have limited access to targeted cancer therapies. The transitional nature of these economies has influenced health care funding, which has resulted in the unavailability of targeted cancer treatments.1,2 Besides the three studies that will be described here, to our knowledge, no literature exists on the clinical outcome of patients treated with delayed targeted cancer therapy. To raise awareness on the importance of timely targeted cancer treatment, we will discuss three key issues: (1) the low number of targeted cancer therapies for different cancers, (2) the delay in cancer treatment, and (3) the unavailability of cancer diagnostics.

Low Number of Targeted Cancer Therapies for Different Cancers

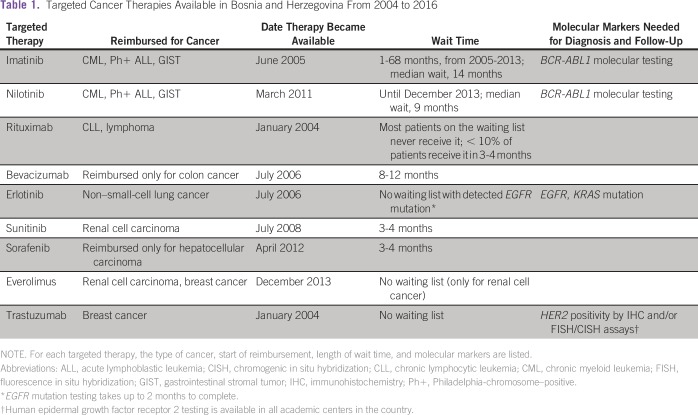

From our experience in Bosnia, the majority of patients with cancer who require targeted therapy are faced with two options: (1) they never receive the therapy because it is not found on the list of government-reimbursed drugs, or (2) they are put on the waiting lists for one of nine available drugs that are reimbursed. Currently, only nine targeted cancer treatments are available in Bosnia through the Solidarity Fund, a subsidiary of the federal government responsible for the allocation of expensive drugs. The list of targeted treatments, the cancers that they are approved for, and the length of the wait-list for each therapy are listed in Table 1. Funded therapies include imatinib and nilotinib for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), Philadelphia-chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST); rituximab for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and lymphoma; bevacizumab for colon cancer only (not reimbursed for renal cell carcinoma; Table 2); erlotinib for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–mutated non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC); sunitinib for renal cell carcinoma; sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma only (not for renal cell carcinoma; Table 2); everolimus for renal cell carcinoma and breast cancer; and trastuzumab for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancer. There is no waiting for imatinib, erlotinib, everolimus, and trastuzumab for the indications given previously. The Solidarity Fund was created in 2004, and the list of the nine funded cancer therapies has not been updated in years—the first drug was approved in January 2004 (rituximab), and the last one was approved in December 2013 (everolimus; Table 1).

Table 1.

Targeted Cancer Therapies Available in Bosnia and Herzegovina From 2004 to 2016

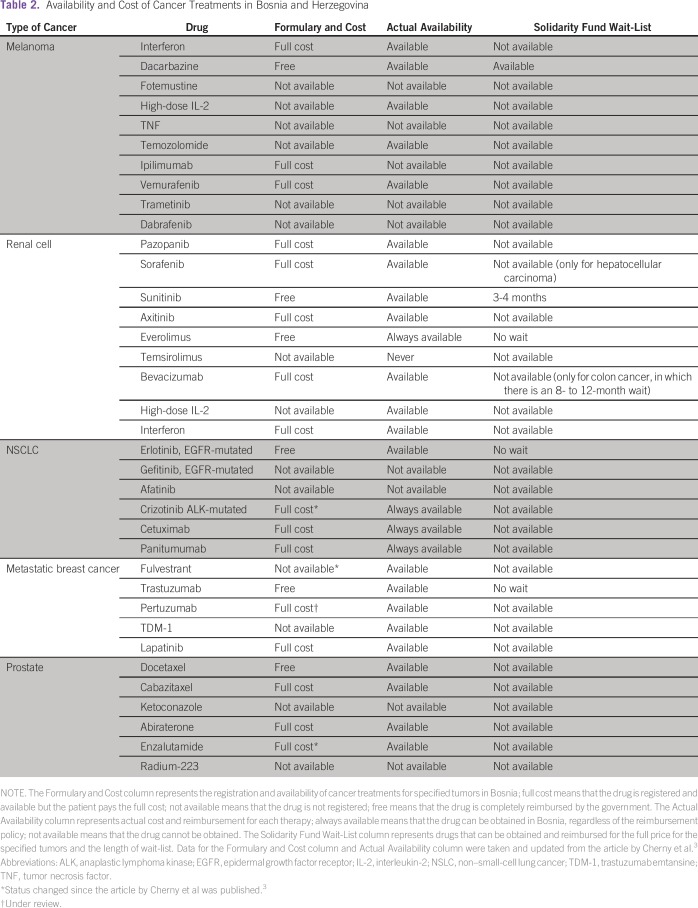

Table 2.

Availability and Cost of Cancer Treatments in Bosnia and Herzegovina

A recent survey by the European Society for Medical Oncology reviewed the availability of cancer therapies in Europe, with the aim of evaluating the formulary and out-of-pocket costs, as well as the actual availability of the medication (Table 2).3 From their report, which is updated in Table 2, it is clear that most cancer drugs for melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, NSCLC, metastatic breast cancer, and prostate cancer are not freely available in Bosnia. For example, drugs such as pazopanib, crizotinib, ipilimumab, vemurafenib, and panitumumab are available at all times for patients to pay at full cost (there is no copay through governmental insurance). It is important to note that most people are insured through governmental insurance, and private insurance systems do not function widely in Bosnia. New cancer treatments may be available to some patients through the few clinical trials that are conducted in four clinical centers, in Sarajevo, Tuzla, Banja Luka, and Mostar.

Delay in Cancer Treatment

The waiting lists for targeted cancer therapies have existed since 2004, and depending on the therapy, the wait could be from several months to years. Besides the lack of new cancer treatments, patients who can be treated with the available drugs have to wait for the therapy (Table 1). The estimation of the length of the wait time has been based on the Solidarity Fund’s committee evaluation, which meets monthly and assigns the targeted therapies to patients after the hematologist/oncologist’s application. Patients are placed on the long waiting lists for each drug, which function on a first-come, first-serve basis. Thus, treatment delay is the norm and not the exception. Two country-wide studies in Bosnia and Lithuania have shown the deleterious effects of delayed targeted treatment (imatinib mesylate) for patients with CML.1,2 CML is a rapidly progressing disease, and 17% of patients in the last 10 years died before receiving the required therapy in Bosnia. For imatinib mesylate, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) given to patients with CML and GIST, waiting lists have existed from 2005 to 2013 in Bosnia and Lithuania. In Bosnia, more than 65% of patients with CML received imatinib after a median waiting period of 14 months. Delayed targeted treatment affected significantly all patient outcomes, including survival and cytogenetic and molecular response.1 At 5 years, the survival rate was 0% for patients who never received TKI (n = 23), 91% for immediate treatment (0-5 months), 81% for patients who waited 6 to 12 months, and 64% for patients who waited > 13 months. After 1 year of therapy, cytogenetic response was achieved in 67% of patients in the immediate imatinib-treatment group, compared with 15% of patients in the group who waited > 13 months.1

The Lithuanian study also reported delayed imatinib treatment, where most patients > 64 years of age never received imatinib.2 Similar to Bosnia, imatinib became partially available in Lithuania in 2005. During the period from 2005 to 2009, imatinib was reserved only for the youngest patients—only 8% of patients > 55 years of age received imatinib. After 2011, all newly diagnosed patients with CML received imatinib as a first-line treatment. However, from 2010 to 2013, 69% of all patients with CML were treated with TKIs.2

At present, more than 120 patients with colon cancer are on the waiting list for bevacizumab in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Patients with GIST (n = 145) diagnosed in the last 10 years in Bosnia also had to wait for the imatinib treatment (range, 0-67 months; median, 17 months), but their outcome was not affected, probably because of the biology of the disease.4

Unavailability of Molecular Cancer Diagnostics

Apart from the delayed therapy caused by the lack of funding, the delay in the targeted therapy for Bosnian patients may be related to the insufficient molecular profiling essays that provide the predictive biomarkers for targeted therapy. Thus, EGFR and KRAS testing for NSCLC is performed in one academic center in the country and has been funded by the Roche BiH d.o.o. since 2012. This is the only centralized molecular testing program in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and despite it, the program is not devoid of the inconsistent data caused by both preanalytical and analytical factors.

HER2 testing is performed for all newly diagnosed and recurrent/distant metastatic breast cancers and advanced gastric cancer, as recommended by the most recent guidelines. The testing includes immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (mainly chromogenic) assays. Although IHC assay is performed in all histopathology laboratories across the country, chromogenic in situ hybridization assays for HER2/neu gene amplification evaluation is performed in only three laboratories in the country (two laboratories in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina [Sarajevo and Tuzla] and one laboratory in Republika Srpska [Banja Luka]). The central pathology laboratory in Sarajevo is included in the external quality control assessment for HER2 testing performed by the NordiQC. HER2 testing and external quality control are in part funded by the local pharmaceutical companies. In 2016, the central pathology laboratory in Sarajevo performed 440 HER2 IHC assays (380 breast and 60 gastric cancer assays) and 55 chromogenic in situ hybridization assays. Overall, HER2 positivity in breast cancer was 18%. Predictive molecular tests for melanoma, colorectal carcinoma, and other cancers (eg, BRAF, KRAS, MSI) are not widely available. ALK and ROS gene testing for NSCLC are not available at all.

The importance of studying the effects of delayed therapy or the lack of targeted cancer therapy in patients transcends the local and individual level and extrapolates to a more global health care issue, because many developing and low-income countries have gradually introduced targeted cancer therapy, but still have patients whose clinical outcome may be affected by the delayed access to the targeted treatment modalities.1,2,4-6 In Bosnia, the causes could be found in the lack of governmental funding and the lack of unified health policy caused by the complicated political system of postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina. Therefore, the solution to this issue lies in the joint efforts of health care professionals, governmental stakeholders, and patient associations to overcome the present situation and improve both the molecular diagnostics and increase the availability of the targeted cancer treatment modalities.

In conclusion, we have an increasing number of available targeted treatments in the developed world. However, in low- and middle-income countries, we are witnessing an increasing number of patients with cancer7 that is accompanied by the limited number of targeted therapies and their precision diagnostics. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, only a limited number of targeted cancer treatments are available for reimbursement by the government (Table 2). One reason for this is the unclear application procedure for the introduction of new drugs on the reimbursement list. Also, no clear guidelines and timeframe have been instituted for the reviews of the actual drug lists. In addition, the available cancer medicines are subjected to yearly tender procedures, which are often late and create long delays in availability. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, there is a clear political impact on health policy in cancer medicine because making these drugs available depends on the willingness of the ministries of health to comprehend the importance of optimal cancer treatment. Furthermore, public and health professionals do not exercise the required pressure to start solving the problem.

Thus, we appeal to the researchers, physicians, and public from low-income and developing countries to conduct more systematic studies to highlight the causes and effects of the lack of access to targeted therapy. We hope that the Bosnian experience will initiate global efforts that eventually will enable more access to targeted cancer treatment modalities in the era of precision (personalized) medicine.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Amina Kurtovic-Kozaric

No relationship to disclose

Semir Vranic

Honoraria: Caris Life Sciences

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche

Sabira Kurtovic

No relationship to disclose

Azra Hasic

No relationship to disclose

Mirza Kozaric

No relationship to disclose

Nermir Granov

No relationship to disclose

Timur Ceric

Honoraria: Roche, Novartis, Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Novartis, Pfizer

REFERENCES

- 1.Kurtovic-Kozaric A, Hasic A, Radich JP, et al. The reality of cancer treatment in a developing country: The effects of delayed TKI treatment on survival, cytogenetic and molecular responses in chronic myeloid leukaemia patients. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:420–427. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beinortas T, Tavorienė I, Žvirblis T, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia incidence, survival and accessibility of tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A report from population-based Lithuanian haematological disease registry 2000-2013. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:198. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2238-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherny N, Sullivan R, Torode J, et al. ESMO European Consortium Study on the availability, out-of-pocket costs and accessibility of antineoplastic medicines in Europe. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1423–1443. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurtovic-Kozaric A, Kugic A, Hasic A, et al. Long-term outcome of GIST patients with delayed imatinib therapy. Eur J Cancer (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Bengió RM, Riva ME, Moiraghi B, et al. Clinical outcome of chronic myeloid leukemia imatinib-resistant patients: Do BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations affect patient survival? First multicenter Argentinean study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52:1720–1726. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.578310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conti RM, Padula WV, Larson RA. Changing the cost of care for chronic myeloid leukemia: The availability of generic imatinib in the USA and the EU. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:S249–S257. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2319-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Printz C. Increasing cancer rates threaten economic stability in low- and middle-income countries. Cancer. 2016;122:501. [Google Scholar]