Abstract

Patient: Male, 62

Final Diagnosis: Mitral valve aneurysm complicating aortic valve endocarditis

Symptoms: Fever

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Combined aortic valve and mitral valve replacement

Specialty: Cardiology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Mitral valve aneurysms (MVAs) are uncommon conditions frequently associated with aortic valve endocarditis. They may be complicated by perforation and severe mitral regurgitation (MR). Optimal treatment of MVA, and in particular the best timing for surgery, are uncertain.

Case Report:

A 62-year-old man with a recent history of dental surgery presented to the Emergency Department complaining relapsing fever. A first echocardiogram demonstrated infective endocarditis of the aortic valve. The patient was primarily managed with specific antibiotic therapy. Despite this, a few days later he suffered from splenic embolization and an MVA with MR was detected. Surgical replacement of the mitral and aortic valves was therefore performed.

Conclusions:

MVAs are infrequent but potentially severe complications of AV endocarditis. In the absence of definite treatment indication, the correct time for surgery should depend on concomitant clinical and infective features.

MeSH Keywords: Aortic Valve, Cardiac Surgical Procedures, Echocardiography, Endocarditis, Mitral Valve Insufficiency

Background

Mitral valve aneurysms (MVAs) are uncommon entities usually associated with aortic valve (AV) endocarditis [1–5]. Among other complications, they bear a high risk of perforation with subsequent acute severe mitral regurgitation (MR). However, the optimal treatment for MVAs, and in particular timing of surgery, is not well defined.

We present a case of AV endocarditis with associated aortic regurgitation (AR), initially managed with antibiotic therapy, but complicated by the occurrence of MVA and MR. In addition to MVA, other clinical evidence of uncontrolled infection was detected; the patient therefore underwent cardiac surgery with mitral valve (MV) and AV replacement.

Case Report

A 62-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department complaining of relapsing fever, which was poorly responsive to an empirical antibiotic treatment with cephalosporins. He had undergone dental surgery 2 months before.

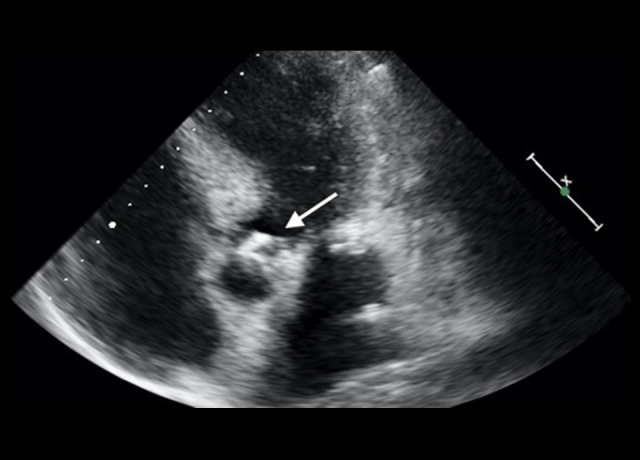

A first transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) showed a 4-mm-long image compatible with a vegetation involving the AV (Figure 1), with associated moderate AR, raising suspicion of infective endocarditis (IE) of the AV.

Figure 1.

First transthoracic echocardiography. Apical 5-chamber view showing aortic valve endocarditis vegetation.

The likelihood of IE was strengthened by positive blood cultures for Streptococcus sanguis. Targeted antibiotic therapy with ampicillin (12 g per day) was started.

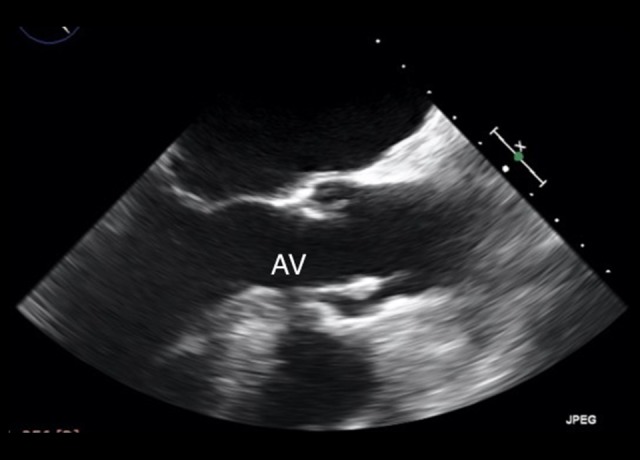

A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) was then performed and confirmed the AV vegetation and the moderate AR, characterized by an eccentric jet directed toward the anterior mitral leaflet (AML). Mild MR was also detected, and a thin filiform structure involving the AML was noted (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

First transesophageal echocardiography. Long-axis view showing aortic valve endocarditis vegetation.

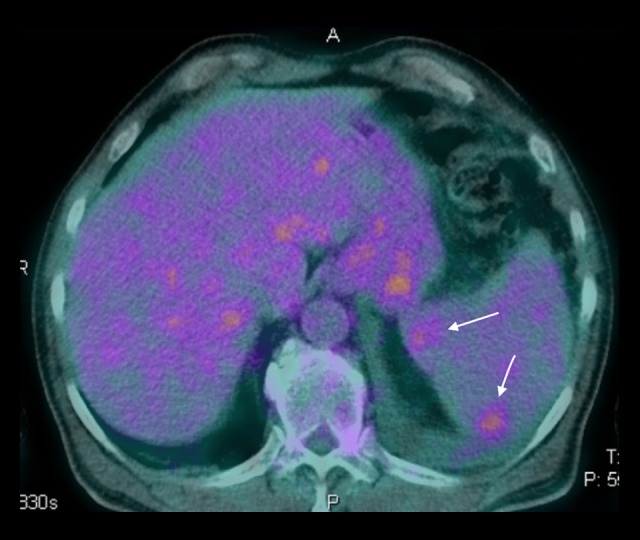

The patient was hemodynamically stable, with no signs or symptoms of heart failure. Clinical improvement was seen after initiation of specific antibiotic treatment: his temperature normalized and blood cultures and inflammatory markers became negative. Despite this, after 9 days, he suffered from sudden onset of bilateral hypoacousia, confirmed by audiometry. Urgent positron emission tomography (PET) and cranial computed tomography (CT) were performed due to suspicion of endocarditis embolization. Cerebral imaging was normal, but the PET study revealed evidence of splenic embolization (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Positron emission tomography (PET). Axial plane reconstruction demonstrating splenic embolization (arrows).

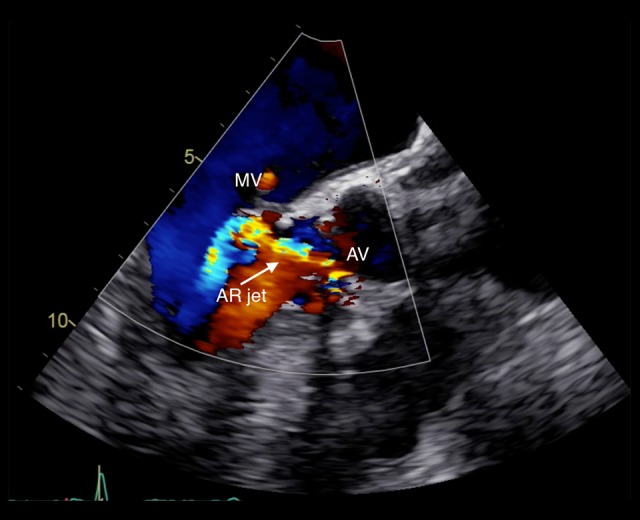

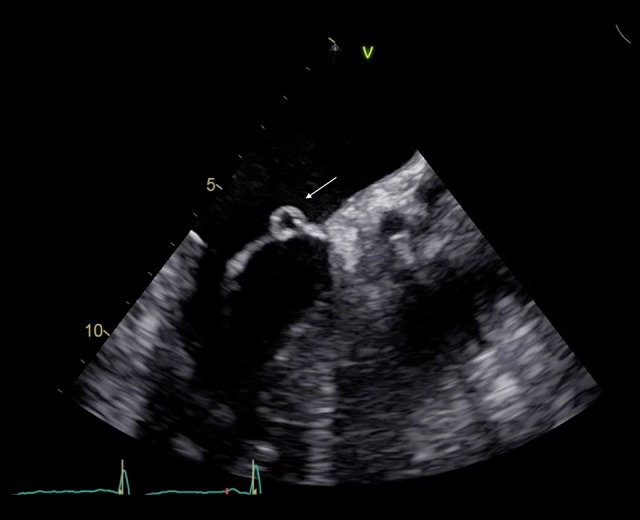

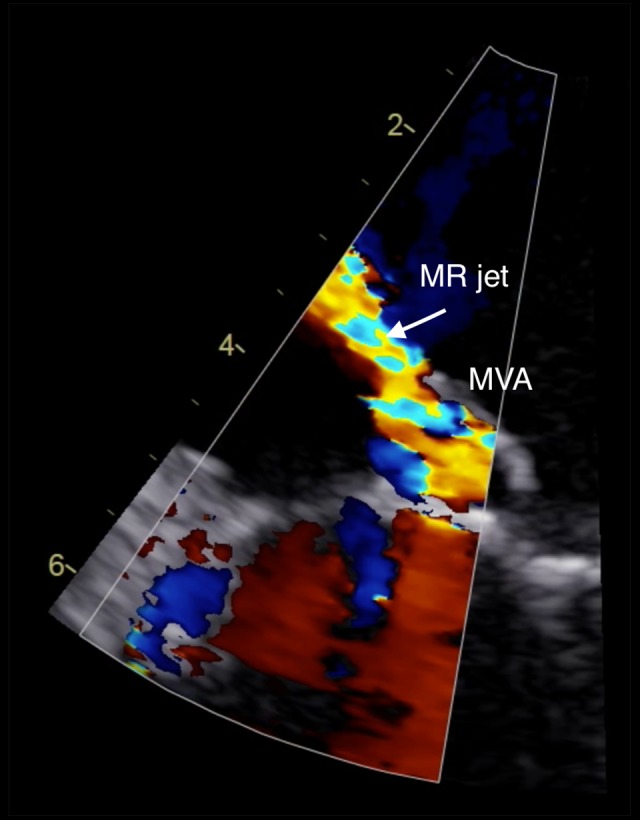

TTE and TEE were repeated and showed worsening of AR. Moreover, an MVA, identified as a saccular bulge protrusion located on the AML, with systolic expansion and diastolic collapse, was detected. Color Doppler imaging demonstrated perforation of the saccular bulge protrusion with moderate MR (Figures 4–6, Video 1).

Figure 4.

Transesophageal echocardiography. Long-axis view color Doppler showing aortic valve regurgitant jet striking the anterior mitral valve leaflet.

Figure 5.

Transesophageal echocardiography. Long-axis view showing perforated left anterior mitral valve aneurysm.

Figure 6.

Transesophageal echocardiography. Zoomed long-axis view color Doppler showing mitral regurgitation through perforated mitral valve aneurysm.

Video 1.

Transesophageal echocardiography. Cine frame of a zoomed long-axis view.

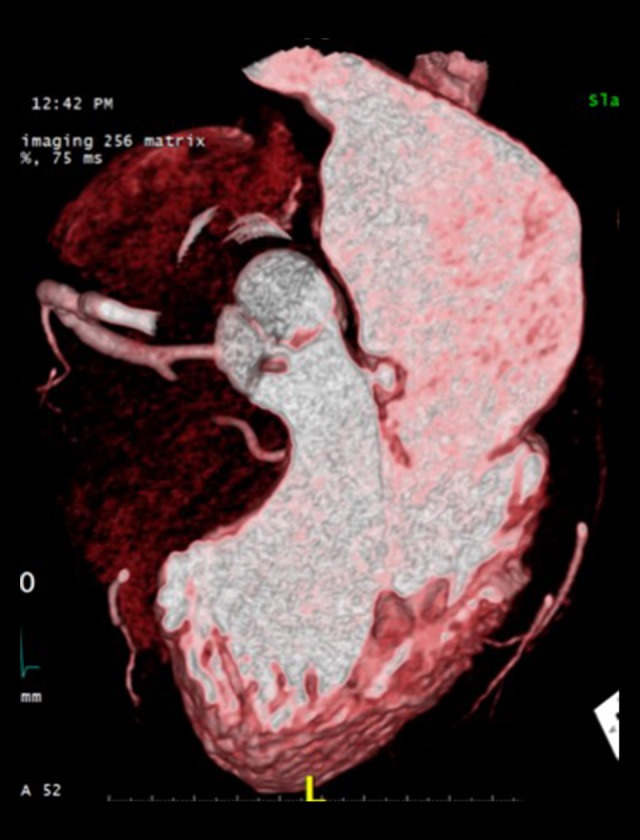

A cardiac CT study confirmed a 7-mm AV vegetation on the right cuspid and an associated abscess (13×17 mm) protruding toward the left atrium and in continuity with the AML (A1 scallop) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Cardiac CT. Three-chamber view showing aortic valve vegetation and mitral valve aneurysm.

In consideration of the worsening of AR and MR, and due to splenic embolization and evidence of MVA complicated by perforation, signs of uncontrolled infection despite 12 days of specific antibiotic treatment, the patient was scheduled for surgery. Eighteen days after hospital admission, he underwent combined AV replacement (Perimount Magna Aortic Ease n°23) and MV replacement (Perimount Magna Ease n°29), without complications (Figure 8). He was discharged 10 days later and to date is doing well.

Figure 8.

Surgical picture. View from the aortic root of a fissurated mitral valve leaflet.

Discussion

The first case of MVA was reported by Morand in 1729 [1].

MVAs are uncommon conditions and are usually a complication of AV endocarditis [1–5]. They are rarely encountered in patients without endocarditis. Sporadic cases are reported in association with particular conditions, such as connective tissue diseases (e.g., Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, and osteogenesis imperfecta), extreme forms of MV prolapse (e.g., MVP), congenital cardiac structural defects, or Libman-Sacks endocarditis [5–10].

Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain the development of MVA in the setting of AV endocarditis. There have been reports of cases with a direct extension of the infection to the AML through the mitral-aortic intervalvular fibrosa with abscess formation and drainage [2,4,11–15]. Another suggested explanation is the “jet lesion”, which is the infected aortic regurgitant jet striking the AML, leading to secondary infection of the MV and resulting in the formation of a leaflet aneurysm [2]. Third, the direct contact of a prolapsing aortic vegetation with the AML may cause transmission of infection to the MV and formation of MVA [15]. Notably, the “jet lesion” mechanism seems to be of particular importance in the formation of MVA [2], probably due to the trauma caused to MV leaflets by the regurgitant jet.

In the case presented here, a combination of the first 2 mechanisms may be considered responsible for MVA occurrence, since the CT study showed an abscess of continuity with the MV, and the AR from the infected AV was directed toward the MV and struck the AML.

TTE and TOE are the mainstay of diagnostic imaging methods [16], although three-dimensional (3D) echocardiography has also demonstrated great utility for this purpose.

The echocardiographic appearance of MVA is a saccular bulge of the mitral leaflets, typically protruding into the left atrium during systole and collapsing during diastole [3].

Anterior MVAs are more common than posterior MVAs [17–19].

The differential diagnosis of MVA includes MVP, myxomatous degeneration of the MV, flail mitral leaflet, chordal rupture, papillary fibroelastoma, atrial myxoma involving the MV, blood cyst of the papillary muscle, and anterior MV diverticulum [17,20]. MVP, the most common condition among those mentioned above, can be distinguished from MVA by the diffuse leaflet thickening, the protrusion of the leaflet tip into the left atrium during systole, and the absence of a discrete neck [21].

Several complications of MVA are possible. The most frequent and important is perforation of the aneurysm, as in the case presented here. Perforation may lead to acute severe MR and pulmonary edema [22,23]. Larger aneurysms are considered to pose more risk of rupture than smaller ones, although risk of perforation has been shown to have no relation to size [24]. Beyond perforation, MR in MVA can occur due to other reasons. MVA is associated with spread of infection to the MV and thus to IE-induced degeneration of the valve and subsequent MR [24]. Moreover, MVA may cause a mass effect, leading to coaptation defect of the leaflets [5].

Another serious potential complication of MVA is thrombus formation within the saccular bulge, with high risk of embolism and spreading of infection [8].

No definite indications for treatment of MVAs exist. Surgery should definitely be considered in case of perforation or rupture, with severe MR and signs of heart failure. Moreover, it might also be taken into consideration even without significant MR or heart failure, if concomitant evidence of uncontrolled infection is present [24,27]. Basically, the decision of whether to perform surgery or to conservatively follow up a patient should rely on the dimension of the MVA and clinical status of the patient. A conservative approach for small, uncomplicated aneurysms is a reasonable option, while the surgical option may be suitable in cases of large unruptured aneurysms with clear evidence of thrombosis and therefore with a high risk of embolization.

In our patient, a medical and conservative approach was initially preferred due to the small size of the AV vegetation and low risk of embolization. However, despite the prolonged period of specific antibiotic treatment with blood culture results becoming negative, we not only observed increasing size of the AV vegetation with worsening of AR, but also occurrence of perforated MVA and distal embolization; therefore, this indicated the need for surgery. Notably, the clue that led us to investigate a possible distal endocarditis embolization was the sudden onset of bilateral hypoacousia. The cerebral CT scan and PET did not find any sign of cerebral emboli, but hypoacousia was clearly confirmed by audiometry and no other clear causes for it were present, and the antibiotic therapy prescribed (ampicillin) does not have ototoxicity as a possible adverse effect. One may speculate that a small endocarditis cerebral embolization occurred that was not detected by imaging. This hypothesis is unlikely but cannot be excluded.

MV repair, primarily or using synthetic or pericardial patch, in the setting of IE has been shown to have better clinical in-hospital and long-term results as compared to MV replacement [28,29]. Prosthetic valve replacement may be considered in patients unsuitable for repair or with persistent MR following repair. The best time for surgery is unclear. Ruparelia [30] suggested surgery as soon as MVA is observed, in order to prevent other complications. On the other hand, Vilacosta [3] and other authors suggested the possibility of conservative management, with surgical intervention only in case of cardiac deterioration [13,31,32].

Early surgery for IE has been advocated in general. Several case series have reported that, in comparison with conventional treatment, early surgical treatment yields better long-term outcomes and less risk of peripheral embolization [33–36], but it can present technical difficulties associated with weak and infected tissue. A period of antibiotic therapy before surgery can prevent possible extra-valvular involvement, especially on the intervalvular fibrous body. Simplifying operations is an important benefit of presurgical antibiotic therapy, because less extensive surgery is clearly associated with less operative risk [37].

Conclusions

MVAs are infrequent but potentially severe complications of AV endocarditis. They may occur as a consequence either of direct extension of infection to the MV or of significant AR with an eccentric jet directed toward the AML. Severe MR or embolization are possible consequences of MVAs that may worsen the clinical course and the hemodynamic stability of the patient.

Given uncertainty about optimal treatment of IE with this specific complication, correct timing of surgery in MVA should depend on concomitant clinical and infective features.

Abbreviations:

- AML

anterior mitral leaflet;

- AV

aortic valve;

- AR

aortic regurgitation;

- CT

computed tomography;

- IE

infective endocarditis;

- MR

mitral regurgitation;

- MVA

mitral valve aneurysm;

- MV

mitral valve;

- MVP

mitral valve prolapse;

- PET

positron emission tomography;

- TEE

transesophageal echocardiogram;

- TTE

transthoracic echocardiogram

References:

- 1.Jarcho S. Aneurysm of heart valves. Am J Cardiol. 1968;v22:273–76. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(68)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid C, Chandraratna A, Harrison E, et al. Mitral valve aneurysm: Clinical features, echocardiographic-pathologic correlations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;2:460–64. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vilacosta I, Román J, Sarriá C, et al. Clinical, anatomic, and echocardiographic characteristics of aneurysms of the mitral valve. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:110–13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raval A, Menkis A, Boughner D. Mitral valve aneurysm associated with aortic valve endocarditis and regurgitation. Heart Surg Forum. 2002;5:298–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guler A, Karabay C, Gursoy O, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic evaluation of mitral valve aneurysms: A retrospective, single center study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30:535–41. doi: 10.1007/s10554-014-0365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kathir K, Dunn RF. Congenital obstructive mitral valve aneurysm. Int Med J. 2003;33:541–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2003.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruckel A, Erbel A, Henkel B, et al. Mitral valve aneurysm revealed by cross-sectional echocardiography in a patient with mitral valve prolapse. Int J Cardiol. 1984;6:633–37. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(84)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takayama T, Teramura M, Sakai H, et al. Perforated mitral valve aneurysm associated with Libman-Sacks endocarditis. Int Med. 2008;47:1605–8. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edynak G, Rawson A. Ruptured aneurysm of the mitral valve in a Marfan-like syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1963;11:674–77. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lebwohl MG, Distefano D, Prioleau PG, et al. Pseudo-xanthoma elasticum and mitral-valve prolapse. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:228–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207223070406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maclean N, Macdonal M. Aneurysm of the mitral valve in subacute bacterial endocarditis. Br Heart J. 1957;19:550–54. doi: 10.1136/hrt.19.4.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai T, Moody J, Sako E. Mitral valve aneurysm due to severe aortic valve regurgitation. Circulation. 1999;100:e53–56. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.12.e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao C, Xiao C, Li B. Mitral valve aneurysm with infective endocarditis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:2171–73. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01602-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Citro R, Silverio A, Ascoli R, et al. Anterior mitral valve aneurysm perforation in a patient with pre-existing aortic regurgitation. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2012;78:210–11. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2012.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piper C, Hetzer R, Korfer R, et al. The importance of secondary mitral valve involvement in primary aortic valve endocarditis. The mitral kissing vegetation. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:79–86. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cziner DG, Rosenzweig BP, Katz ES, et al. Transesophageal versus transthoracic echocardiography for diagnosing mitral valve perforation. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:1495–97. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90911-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guler A, Karabay CY, Gursoy OM, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic evaluation of mitral valve aneurysms: A retrospective, single center study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30:535–41. doi: 10.1007/s10554-014-0365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawai S, Oigawa T, Sunayama S, et al. Mitral valve aneurysm as a sequela of infective endocarditis: Review of pathologic findings in Japanese cases. J Cardiol. 1998;31(Suppl. 1):19–33. discussion 34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hotchi J, Hoshiga M, Okabe T, et al. Impressive echocardiographic images of a mitral valve aneurysm. Circulation. 2011;123:e400–2. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.984799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stechert MM, Pletcher JR, Tseng EE, et al. Echo rounds: Aneurysm of the anterior mitral valve. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(1):86–88. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318239c4d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg L, Mekel J, Grigorov V. Echocardiographic features of extreme mitral valve prolapse vs. mitral valve aneurysm. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 2002;13(2):73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rachko M, Sa AM, Yeshou D, et al. Anterior mitral valve aneurysm: A subaortic complication of aortic valve endocarditis: A case report and review of literature. Heart Disease. 2001;3:145–47. doi: 10.1097/00132580-200105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vijay SK, Tiwari BC, Misra M, et al. Incremental value of three-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography in the assessment of ruptured aneurysm of anterior mitral leaflet. Echocardiography. 2014;31(1):E24–26. doi: 10.1111/echo.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gin KG, Boone JA, Thompson CR, et al. Conservative management of mitral valve aneurysm. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1993;6:613–18. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(14)80180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aung SM, Güler A, Acar G, et al. Aortic valve aneurysm: A result or reason? Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2011;11(4):E15. doi: 10.5152/akd.2011.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohira S, Doi K, Yamano T, Yaku H. Successful repair of a mitral valve aneurysm with cleft of anterior mitral leaflet in an adult. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(6):2238–40. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) Eur Heart J. 2015;36(44):3075–28. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feringa HH, Shaw LJ, Poldermans D, et al. Mitral valve repair and replacement in endocarditis: A systematic review of literature. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:564–70. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwalm SA, Sugeng L, Raman J, et al. Assessment of mitral valve lea et perforation as a result of infective endocarditis by 3-dimensional real-time echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:919–22. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruparelia N, Lawrence D, Elkington A. Bicuspid aortic valve endocarditis complicated by mitral valve aneurysm. J Card Surg. 2011;26(3):284–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2011.01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kharwar RB, Mohanty A, Sharma A, et al. Ruptured anterior mitral leaflet aneurysm in aortic valve in-fective endocarditis – evaluation by three-dimensional echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2014;31(3):E72–76. doi: 10.1111/echo.12449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eiseman MS, Schroeder AR, Rutkowski PS, et al. An unusual cause of severe mitral regurgitation in a patient with aortic valve endocarditis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28(5):1432–34. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang DH, Kim YJ, Kim SH, et al. Early surgery versus conventional treatment for infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2466–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Funakoshi S, Kaji S, Yamamuro A, et al. Impact of early surgery in the active phase on long-term outcomes in left-sided native valve infective endocarditis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142(4):836–42.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim DH, Kang DH, Lee MZ, et al. Impact of early surgery on embolic events in patients with infective endocarditis. Circulation. 2010;122(11 Suppl.):S17–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delahaye F. Is early surgery beneficial in infective endocarditis? A systematic review. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;104(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomsic A, Li WW, Van Paridon M, et al. Infective endocarditis of the aortic valve with anterior mitral valve leaflet aneurysm. Tex Heart Inst J. 2016;43(4):345–49. doi: 10.14503/THIJ-15-5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]