A dual-core processor, composed of EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs, mediates positive and negative regulation of apical hook development by multiple hormones and light signals.

Abstract

The apical hook protects the meristems of dicot seedlings as they protrude through the soil; multiple factors, including phytohormones and light, mediate apical hook development. HOOKLESS1 (HLS1) plays an indispensable role, as HLS1 mutations cause a hookless phenotype. The ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 (EIN3) and EIN3-LIKE1 (EIL1) transcription factors integrate multiple signals (ethylene, gibberellins, and jasmonate) and activate HLS1 expression to enhance hook development. Here, we found that Arabidopsis thaliana PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR (PIF) transcription factors act in parallel with EIN3/EIL1 and promote hook curvature by activating HLS1 transcription at a distinct binding motif. EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs can promote hook formation in the absence of the other. Jasmonate represses PIF function to inhibit hook development. Like EIN3 and EIL1, MYC2 interacts with PIF4 and hampers its activity. Acting together, EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs alleviate the negative effects of jasmonate/light and facilitate the positive effects of ethylene/gibberellins. Mutating EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs causes a complete hookless phenotype, marginal HLS1 expression, and insensitivity to upstream signals. Transcriptome profiling revealed that EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs additively and distinctly regulate a wide array of processes, including apical hook development. Together, our findings identify an integrated framework underlying the regulation of apical hook development and show that EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs fine-tune adaptive growth in response to hormone and light signals.

INTRODUCTION

Plants encounter numerous threats throughout their life cycle and dynamically adjust their growth patterns in response to the changing environment. As one example, dicot seedlings developing in darkness form an apical hook to protect the fragile cotyledons and shoot apical meristem during emergence from the soil (Silk and Erickson, 1978; Harpham et al., 1991). Mutants with compromised hook curvature have problems protruding through soil, showing the significance of the apical hook (Harpham et al., 1991).

Hook development is regulated by diverse internal and external factors, which makes it a good model for studying the crosstalk between multiple signals. Among these signals, the phytohormones ethylene (ET) and gibberellin (GA) play positive roles, while jasmonate (JA) and light are reported to be negative regulators (Bleecker et al., 1988; Turner et al., 2002; Achard et al., 2003; Mazzella et al., 2014). These factors contribute to establishing or diminishing the proper asymmetric distribution of auxin within the apical region of the hypocotyl, leading to the formation or opening of the apical hook, respectively (Abbas et al., 2013). During the formation process, inner cells within the hook region accumulate more auxin, thereby inhibiting the growth of the inner side. Seedlings exhibit a hookless phenotype when the asymmetrical accumulation of auxin is abolished, for example, by applying naphthylphthalamic acid to block auxin transport or supplying excess 2,4-D (Lehman et al., 1996), underscoring the major effect of auxin on hook development. HOOKLESS1 (HLS1), a putative N-acetyltransferase, has been identified as an essential regulator of hook formation, and mutation of the HLS1 gene causes the eponymous hookless phenotype and the disappearance of auxin asymmetry (Guzmán and Ecker, 1990; Lehman et al., 1996). AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2 (ARF2) was identified as a factor acting downstream of HLS1, based on the findings that an arf2 mutation could partially rescue the hookless phenotype of hls1 and that ARF2 protein levels are decreased by HLS1 (Li et al., 2004). Thus, HLS1 integrates upstream stimuli important for establishing auxin asymmetry.

ET broadly regulates plant growth and development. One well-characterized response to ET is called the “triple response”: Treatment of etiolated seedlings with ET or 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC; the immediate precursor of ET) results in shortening of the hypocotyl and root as well as exaggerated hook curvature (Ecker, 1995). Genetic studies using the triple response as a phenotypic output identified an array of ET signaling components and helped establish a linear model for the ET signaling pathway. In this pathway, ET signaling acts to stabilize two transcription factors, EIN3 and EIL1, which are otherwise subjected to ubiquitination and degradation processes executed by SCFEIN3 BINDING F-BOX PROTEIN1/2(EBF1/2) E3 ligases (Guo and Ecker, 2003; Potuschak et al., 2003; An et al., 2010). HLS1 expression is increased by ET treatment (Lehman et al., 1996; An et al., 2012); moreover, EIN3 and EIL1 promote hook development by directly binding to the HLS1 promoter to activate HLS1 expression (An et al., 2012).

The plant hormone GA is also reported to positively regulate hook development. Both ga1-3 mutants (deficient in GA biosynthesis) and seedlings treated with the GA biosynthesis inhibitor paclobutrazol (PAC) exhibit reduced hook curvature and compromised ET response in hook formation (Achard et al., 2003). DELLAs, key repressors in the GA signaling pathway, were found to physically interact with EIN3 and EIL1 and inhibit their function (An et al., 2012). Upon GA treatment, DELLAs are targeted by the SCFSLEEPY1(SLY1) E3 ligase complex for ubiquitination/degradation (Sasaki et al., 2003; Dill et al., 2004). This activity releases the repression of EIN3 and EIL1 and leads to HLS1 expression activation.

In contrast to ET and GA, JA is reported to inhibit apical hook development (Turner et al., 2002). As an important plant defense hormone, JA also regulates myriad developmental processes. When JA is absent, major repressor JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN (JAZ) proteins are active to bind and restrain downstream transcription factors to shut down the pathway (Chini et al., 2007; Thines et al., 2007). A number of JAZ-interacting transcription factors have been isolated, among which MYC2 is critical for regulating various JA-mediated development processes (Lorenzo et al., 2004; Dombrecht et al., 2007). In the presence of JA, JAZs are subjected to ubiquitination/degradation, and MYC2 is released to trigger specific response (Chini et al., 2007; Thines et al., 2007). JA antagonizes the positive effect of ET on apical hook curvature (Song et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). JA-activated MYC2 inhibits the function of EIN3 and EIL1 in two ways: First, MYC2 activates EBF1 expression by binding to its promoter, in turn promoting degradation of EIN3 and EIL1; second, MYC2 physically interacts with EIN3 and EIL1 to impede their DNA binding ability. By controlling the abundance and activity of EIN3 and EIL1, JA downregulates HLS1 expression and represses hook development (Zhang et al., 2014). The crosstalk between ET and GA, as well as the crosstalk between ET and JA, emphasizes the critical role of EIN3 and EIL1 in responding to upstream stimuli and activating downstream HLS1 expression to enhance hook curvature. Nonetheless, the ein3 eil1 mutant is not irresponsive to JA treatment, suggesting the existence of an additional pathway.

Skotomorphogenesis, which refers to the development of seedlings in darkness, reveals how apical hook formation is tightly regulated by light. Etiolated seedlings of constitutive photomorphogenic mutants, such as constitutive photomorphogenic1 and de-etiolated1 mutants, exhibit severe defects in apical hook formation (Deng et al., 1991; Pepper et al., 1994). Moreover, light exposure induces rapid opening of the apical hook (Liscum and Hangarter, 1993), illustrating the dominant effect of light on hook development. PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTORs (PIFs) are essential components for skotomorphogenesis that inhibit light-responsive genes in darkness. PIFs belong to a bHLH transcription factor subfamily, and the members PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, and PIF5 have been characterized (Ni et al., 1998; Toledo-Ortiz et al., 2003). Light induces the rapid degradation and/or functional inhibition of PIFs to abolish their repressive effect on light-responsive genes (Leivar and Quail, 2011). The pif mutants exhibit a constitutive photomorphogenic phenotype even in darkness, as characterized by a shorter hypocotyl, open cotyledons, and apical hook defects (Shin et al., 2009; Leivar and Quail, 2011). However, the mechanism underlying PIF regulation of hook development has been elusive.

In this study, we show that PIFs promote hook curvature by directly binding to the HLS1 promoter (at sites distinct from the EIN3 binding sites) to activate HLS1 expression. Thus, EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs enhance HLS1 transcription and hook development in parallel. We also show that JA-activated MYC2 interacts with PIF4 and represses its function. Together with previous studies on the regulation of EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs, we propose a unified molecular framework for apical hook development that integrates multiple hormones and light signals.

RESULTS

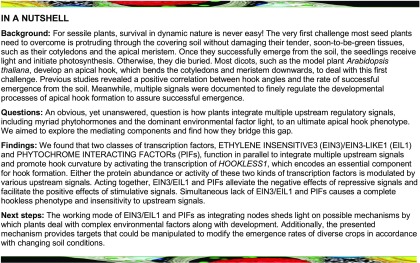

The ein3 eil1 Mutant Is Responsive to PAC and JA Treatments

Our previous study showed that EIN3 and EIL1 are key regulators of HLS1 expression that mediates ET- and GA-induced apical hook formation (An et al., 2012). We also found that JA represses apical hook formation by reducing the abundance and activity of EIN3 and EIL1 (Zhang et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the hook curvature of ein3 eil1 etiolated seedlings was found to be further inhibited by both PAC (a GA biosynthesis inhibitor) and JA treatments in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1), suggesting the existence of additional players in GA/JA-regulated hook development.

Figure 1.

The ein3 eil1 Mutants Are Responsive to PAC- or JA-Mediated Hook Development.

(A) and (B) Three-day-old etiolated seedlings were grown on PAC-gradient medium (A) or JA-gradient medium (B), and the hook phenotype was recorded. Bar = 1 mm.

(C) and (D) Quantification of the hook curvature phenotype in (A) and (B), respectively. The values shown indicated means ± se; n ≥ 15. Significance analysis was based on one-way ANOVA along with Bonferroni correction at a significance level of 0.01. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate a significant difference. Keys show the gradient concentration (μM) of PAC (C) or JA (D), respectively.

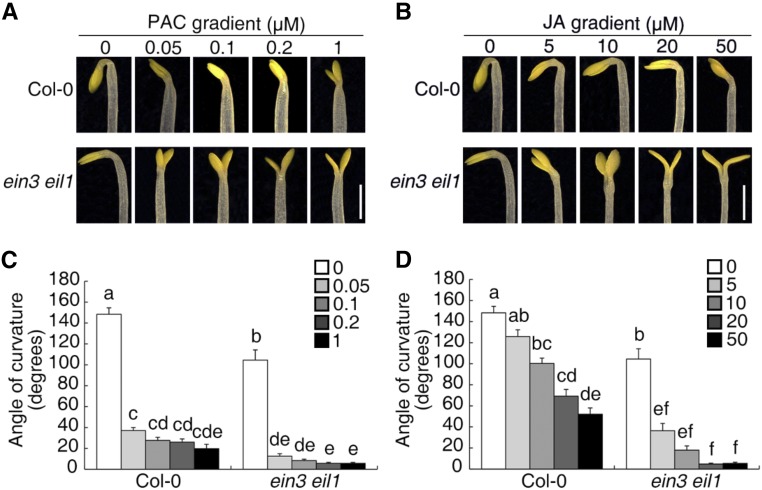

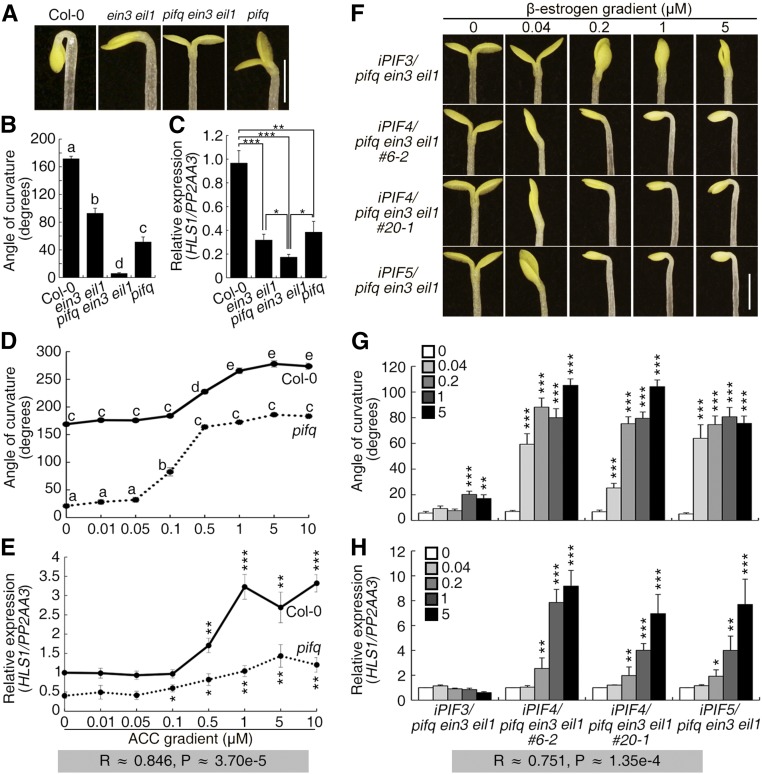

PIFs Positively Regulate Hook Development and HLS1 Expression

PIFs are essential for plant skotomorphogenesis, and apical hook formation typically occurs during skotomorphogenesis (Lehman et al., 1996; Leivar and Quail, 2011). We therefore investigated the effect of PIFs on hook development. Single mutations in four PIFs (PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, and PIF5) resulted in barely detectable hook phenotype defects, but double and triple mutant combinations had increasingly compromised hook curvature. In the pif1 pif3 pif4 pif5 quadruple mutant, hereafter referred to as pifq, the seedling was almost hookless with the two cotyledons open (Figures 2A and 2B). These phenotypes indicate the positive role of PIFs in apical hook formation and the functional redundancy among these four PIFs.

Figure 2.

PIFs Promote Hook Development and HLS1 Expression.

(A) Three-day-old etiolated seedlings were grown on MS medium, and the hook phenotype was recorded. Bar = 1 mm.

(B) Quantification of the hook curvature phenotype in (A). The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 15. Significance analysis was based on one-way ANOVA along with Bonferroni correction at a significance level of 0.01. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate a significant difference.

(C) HLS1 transcript levels of seedlings in (A). HLS1 levels were detected and normalized to PP2AA3. The value for Col-0 was set to 1. The values shown indicate means of biologically repeated experiments (using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions) with sd; n ≥ 3. Significance analysis was based on one-way ANOVA along with Bonferroni correction at a significance level of 0.05. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate a significant difference. R represents the Pearson’s correlation coefficient of hook angles in (B) and HLS1 levels in (C), with significance of P.

(D) Three-day-old etiolated seedlings were grown on β-estrogen gradient medium, and the hook phenotype was recorded. Bar = 1 mm.

(E) Quantification of the hook curvature phenotype in (D). The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 15.

(F) HLS1 transcript levels of seedlings in (D). HLS1 transcript levels were detected and normalized to PP2AA3. The expression level in the respective zero β-estrogen treatment sample was set to a value of 1. The values shown indicate means of biologically repeated experiments (using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions) with sd; n ≥ 3. Keys showed the gradient concentration of β-estrogen. Statistical significance in (E) and (F) was calculated between β-estrogen treatment and the respective zero treatment for each genotype using two-tailed Student’s t test with asterisks denoting statistical significance (***P < 0.001; **0.001 < P < 0.01; *0.01 < P < 0.05). R represents the Pearson’s correlation coefficient of hook angles in (E) and HLS1 levels in (F), with significance of P.

Next, we investigated HLS1 expression in these pif mutants and found that the decreases in HLS1 expression were commensurate with the loss of PIF function, with the lowest HLS1 transcript levels in pifq as well as a positive correlation between HLS1 expression levels and hook angles (Figure 2C). Since PIF1 overexpression results in delayed seed germination (Oh et al., 2004), we constructed transgenic plants harboring β-estrogen-inducible PIF3, PIF4, or PIF5 in the pifq mutant background (iPIF/pifq). As expected, the corresponding gene (PIF3/4/5) and PIL1 (a specific target gene of PIFs) (Leivar and Quail, 2011) were progressively induced upon treatment with increasing dosages of β-estrogen (Supplemental Figures 1A and 1B). The hook phenotype and HLS1 expression were monitored in these transgenic plants, showing that both the hook curvature defects and reduced HLS1 transcript levels of pifq seedlings were reversed after PIF induction (Figures 2D to 2F). Among the different transgenic lines, the increases in hook curvature were in general consistent with the increases in HLS1 expression (Figures 2E and 2F). Despite their functional redundancy, the three PIFs tested had distinct effects on hook development. PIF4 and PIF5 had more profound effects than PIF3 on the induction of hook curvature and HLS1 expression (Figures 2D to 2F). We also noticed that the hook angles decreased at higher levels of PIF4/5 induction relative to their effects at lower induction levels. PIF4 and PIF5 have been shown to induce auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana hypocotyls (Hornitschek et al., 2012), and overdosage of auxin accumulation inhibits hook curvature and hypocotyl growth of etiolated seedlings (Lehman et al., 1996; Alonso et al., 2003). Consistent with this, the transcript levels of an auxin biosynthetic gene YUC8 were elevated upon PIF4/5 induction and the hypocotyl lengths were shorter under treatments with progressively higher β-estrogen concentrations (Supplemental Figures 1C and 1D). Therefore, PIF4/5-promoted auxin biosynthesis may explain the above observations, which resulted in the relatively low correlation between hook angles and HLS1 transcript levels (Figure 2F).

We also expressed inducible PIF4 in the hls1 mutant background and found that the positive effect of PIF4 on hook curvature was largely restricted (Supplemental Figures 1E and 1F). Nonetheless, we observed a subtle but clear bending of the hls1 hook when PIF4 was induced (Supplemental Figures 1E and 1F), suggesting that the ability of PIF4 to enhance apical hook formation is largely but not fully dependent on HLS1. Taking these results together, we conclude that PIFs positively regulate apical hook formation and HLS1 expression.

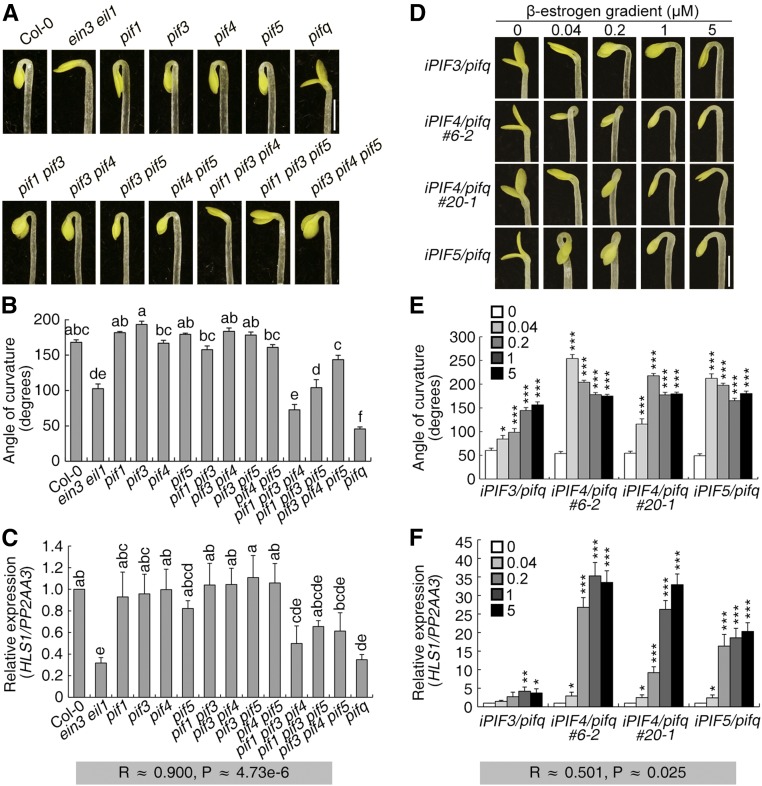

PIFs Promote HLS1 Transcription by Directly Binding to Its Promoter

Considering the direct regulation of HLS1 by EIN3 and EIL1, we further investigated HLS1 expression regulation by PIFs. Given that PIF1 overexpression delays seed germination (Oh et al., 2004), that PIF3 is a target gene of EIN3 and EIL1 (Zhong et al., 2012), and that PIF5 promotes ethylene biosynthesis (Khanna et al., 2007), we primarily focused on PIF4 in subsequent experiments to help exclude potentially indirect effects. Results from a dual-luciferase reporter (DLR) system with a 1.5-kb HLS1 promoter sequence in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves (Supplemental Figure 2A) and Arabidopsis protoplasts (Supplemental Figure 2B) showed that PIF4 promoted the transcription of HLS1. Analysis of the HLS1 promoter sequence identified several E-box motifs as putative PIF binding sites (Martínez-García et al., 2000; Oh et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2013; Pfeiffer et al., 2014). An in vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed using iPIF4/pifq as well as pifq seedlings, and the following fragments within the HLS1 promoter were amplified: five specific binding sites (A-, B-, and C-containing E-box motifs; EBS-containing EIN3 binding sites; and a D-containing a G-box-like motif) and two unrelated regions (E and 3′ untranslated region as negative controls) (Figure 3A). Compared with the enrichment in pifq, the negative control samples, PIF4 induction in iPIF4/pifq samples specifically enriched fragments A and B, with a particularly noticeable effect for fragment A (Figure 3B). Control experiments were also performed, and PIF4 induction enriched the promoter fragment of PIL1 but not ACT2 (Supplemental Figures 2C and 2D).

Figure 3.

PIF4 Directly Binds to an Element in the HLS1 Promoter to Activate HLS1 Transcription.

(A) Schematic illustration of the HLS1 promoter region. “ATG” indicates the first codon, and HLS1_EBS indicates the confirmed EIN3 binding sites. HLS1A, HLS1B, and HLS1C contain E-box motifs; HLS1D contains a similar sequence with a G-box motif; and HLS1E corresponds to 5′ end sequences. The nucleotide sequences of candidate binding sites are noted.

(B) ChIP-PCR for the in vivo binding of PIF4 with HLS1A. Seedlings were grown on 5 μM β-estrogen medium for 3 d. Cross-linked chromatin was precipitated with anti-MYC antibody, and the eluted DNA was subjected to RT-PCR for the sequences in (A). The enrichment values of the various fragments in iPIF4/pifq were normalized to those in pifq (set to a value of 1). Statistical significance was calculated between relative enrichment of fragment A in iPIF4/pifq and those of other fragments (E, C, B, EBS, D, and 3′ untranslated region [UTR]) in iPIF4/pifq, respectively, using two-tailed Student’s t test with asterisks denoting statistical significance (**0.001 < P < 0.01; *0.01 < P < 0.05).

(C) An HLS1 probe containing an E-box motif (CAAATG) was selected from the HLS1A fragment and used for the EMSA experiment.

(D) EMSA results showing the in vitro binding of the PIF4 C terminus to the HLS1 promoter. TF-PIF4C (PIF4 201–430 amino acids fused with HIS-tagged trigger factor) was purified in vitro and incubated with 16 fmol DIG-labeled hot probe or 4 pmol unlabeled “cold” or mutant cold (mCold) probe. TF protein (HIS-tagged trigger factor) was used as a negative control.

(E) Schematic illustration of effectors and reporters used in the DLR experiment. The E-box motif within the fragment (CAAATG in ProHLS1_WT) was either mutated (ACTTCA, ProHLS1_M) or deleted (ProHLS1_Δ).

(F) Transient DLR assays illustrated the requirement for the E-box motif within HLS1_A. Reporter and effector plasmids were combined as indicated then transformed into pifq ein3 eil1 protoplasts. The effects of PIF4 on the three reporters were normalized to the respective empty effectors (set to a value of 1) for comparability. The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 3. Statistical significance was calculated between the various effectors and the empty controls using a Student’s t test with asterisks denoting statistical significance (***P < 0.001).

We next examined the in vitro binding of PIF4 with the fragment A harboring an E-box motif (named HLS1_PBS) using electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs; Figure 3C). Incubation with TF-PIF4C protein (C-terminal bHLH domain of PIF4 fused with HIS-tagged trigger factor) led to a shift for the HLS1_PBS probe (Figure 3D, lanes 2 and 3). The addition of unlabeled probe competed with the binding between TF-PIF4C and HLS1_PBS probe, while the addition of unlabeled mutated probe (with the E-box motif mutated from CAAATG to ACTTCA) failed to compete (Figure 3D, lanes 4 and 5). As a negative control, the addition of TF protein (HIS-tagged trigger factor) did not bind or shift the HLS1_PBS probe (Figure 3D, lanes 1 and 2).

Taking advantage of the DLR system in Arabidopsis protoplasts, we modified the HLS1 promoter (mutating the E-box motif from CAAATG to ACTTCA or deleting the E-box motif) fused to the luciferase gene (Figure 3E). Both modifications of the E-box motif (mutation and deletion) abolished the induction by PIF4 (Figure 3F), supporting the essential role of the E-box motif for this regulation. Taken together, these results demonstrate that PIFs (or at least PIF4) can promote HLS1 transcription by directly binding to its promoter region.

PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 Promote Hook Formation in Parallel

We next explored the relationship between EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs, two different classes of transcription factors that positively regulate HLS1 expression and hook development. The pifq ein3 eil1 sextuple mutants were generated by genetic crossing, and they exhibited a virtually complete hookless phenotype and had lower HLS1 transcript levels than Col-0, pifq, and ein3 eil1 (Figures 4A to 4C). To determine whether EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs require each other for functionality, we performed two analyses. First, Col-0 and pifq etiolated seedlings were treated with the ethylene precursor ACC or ethylene. When exposed to ethylene, EIN3 and EIL1 proteins accumulated in both Col-0 and pifq seedlings (Supplemental Figure 3A). On ACC-gradient medium, the hook curvature of the pifq mutant was gradually enhanced, and HLS1 expression increased as the ACC concentration increased (Figures 4D and 4E). This finding suggests that the promotion of hook development and HLS1 expression by EIN3/EIL1 does not necessarily require PIFs.

Figure 4.

EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs Promote Hook Curvature and HLS1 Expression in Parallel.

(A) Three-day-old etiolated seedlings were grown on MS medium, and the hook phenotype was recorded. Bar = 1 mm.

(B) Quantification of the hook curvature phenotype in (A). The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 15. Significance analysis was based on one-way ANOVA along with Bonferroni correction at a significance level of 0.01. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate a significant difference.

(C) HLS1 transcript levels of the seedlings in (A). HLS1 levels were detected and normalized to PP2AA3. Col-0 was designated as the calibrator and set to a value of 1. The values shown indicate means of biologically repeated experiments (using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions) with sd; n ≥ 3. Statistical significance was calculated between noted samples using two-tailed Student’s t test with asterisks denoting statistical significance (***P < 0.001; **0.001 < P < 0.01; *0.01 < P < 0.05).

(D) Three-day-old etiolated seedlings were grown on ACC gradient medium, and the hook angles were quantified. The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 15. Significance analysis was based on one-way ANOVA along with Bonferroni correction at a significance level of 0.01. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate a significant difference.

(E) HLS1 transcript levels of the seedlings in (D). HLS1 levels were detected and normalized to PP2AA3. Col-0 with 0 µm ACC was designated as the calibrator and set to a value of 1. The values shown indicate means of biologically repeated experiments (using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions) with sd; n ≥ 3. Statistical significance was calculated between ACC treatment and zero treatment for Col-0 and pifq, respectively, using two-tailed Student’s t test with asterisks denoting statistical significance (***P < 0.001; **0.001 < P < 0.01; *0.01 < P < 0.05). R represents the Pearson’s correlation coefficient of hook angles in (D) and HLS1 levels in (E), with significance of P.

(F) Three-day-old etiolated seedlings were grown on β-estrogen gradient medium, and the hook phenotype was recorded. Bar = 1 mm.

(G) Quantification of the hook curvature phenotype in (F). The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 15.

(H) HLS1 transcript levels of the seedlings in (F). HLS1 levels were detected and normalized to PP2AA3. The zero β-estrogen treatment control was designated as the calibrator and set to a value of 1. The values shown indicate means of biologically repeated experiments (using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions) with sd; n ≥ 3. Keys show the gradient concentration of β-estrogen. Statistical significance in (G) and (H) was calculated between β-estrogen treatment and the respective zero treatment for each genotype using two-tailed Student’s t test with asterisks denoting statistical significance (***P < 0.001; **0.001 < P < 0.01; *0.01 < P < 0.05). R represents the Pearson’s correlation coefficients of hook angles in (G) and HLS1 levels in (H), with significance of P.

Second, PIF4 induction in pifq ein3 eil1 protoplasts was still able to increase HLS1 transcription (Supplemental Figure 3B). Induction of PIF3, PIF4, or PIF5 in the pifq ein3 eil1 mutant background effectively rescued the hookless phenotype and low HLS1 expression level (Figures 4F to 4H). The levels of PIFs/PIL1 induction were strongly consistent with the increases in hook curvature and HLS1 expression (Supplemental Figures 3D and 3E; Figures 4F to 4H). ChIP-PCR using iPIF4/pifq ein3 eil1 seedlings showed that the induced PIF4 protein enriched the HLS1 promoter (particularly fragment A) and the PIL1 promoter but not the ACT2 gene (Supplemental Figures 3F to 3H). These findings indicate that PIFs enhance hook development and HLS1 expression regardless of EIN3/EIL1 function. It is therefore possible that EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs act largely independently to activate HLS1 transcription and to promote hook formation.

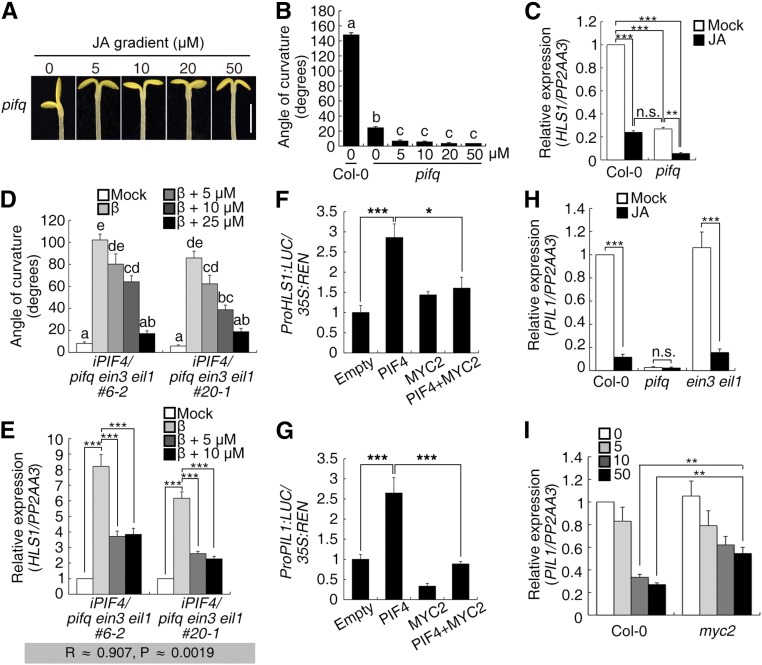

JA Inhibits Hook Development by Repressing PIF Function

Since the hook curvature of ein3 eil1 is still responsive to PAC and JA treatment (Figure 1), we investigated whether PIFs are involved in JA- or PAC-regulated hook development. Previous studies showed that DELLA proteins, a class of negative regulators of GA responses, repress the function of PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 (de Lucas et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2008; An et al., 2012; Li et al., 2016). As observed in ein3 eil1, hook curvature and HLS1 expression in pifq seedlings was further inhibited by PAC treatment (Supplemental Figures 4A and 4B), which would be expected to lead to GA deficiency and DELLA protein accumulation. Consistently, PAC treatment decreased the expression of both PIL1 and EBF2 (Supplemental Figures 4C and 4D), which are target genes of PIFs and EIN3/EIL1, respectively (Konishi and Yanagisawa, 2008; Leivar and Quail, 2011). In contrast, ein3 eil1 mutants showed almost complete insensitivity to ACC and ET treatment in terms of both hook curvature and HLS1 expression (Supplemental Figures 4E and 4F). This finding suggests that the ability of ET to promote hook formation and HLS1 expression is dependent on EIN3/EIL1 but not on PIFs or other factors.

The effect of JA was also studied, and the hook angles of pifq seedlings were reduced when grown on JA medium (Figures 5A and 5B). HLS1 expression in pifq was also further downregulated by JA treatment (Figure 5C). Compared with Col-0, a low concentration of JA treatment resulted in a hookless phenotype in pifq (similar to the phenotype of ein3 eil1), indicating that PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 may counteract JA inhibition of hook development and that loss of either class leads to JA hypersensitivity. We treated the iPIF4/pifq ein3 eil1 transgenic plants with β-estrogen as well as JA and found that in the absence of EIN3/EIL1, PIF4-induced hook curvature and HLS1 expression were inhibited by JA treatment (Figures 5D and 5E).

Figure 5.

JA Inhibits the Function of PIF4 Partially through MYC2.

(A) Three-day-old etiolated seedlings of pifq were grown on JA gradient medium, and the hook phenotype was recorded. Bar = 1 mm.

(B) Quantification of the hook curvature phenotype in (A). The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 15. Angles of Col-0 were taken as control. Significance analysis was based on one-way ANOVA along with Bonferroni correction at a significance level of 0.01. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate a significant difference.

(C) HLS1 transcript levels of Col-0 and pifq seedlings grown on MS or 1 µM JA medium for 3 d. HLS1 levels were detected and normalized to PP2AA3. Col-0 without JA treatment was designated as the calibrator and set to a value of 1. The values shown indicate means of biologically repeated experiments (using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions) with sd; n ≥ 3.

(D) Quantified hook angles of iPIF4/pifq ein3 eil1 seedlings grown on MS, 5 µM β-estrogen, or 5 µm β-estrogen plus JA gradient medium (indicated by keys) for 3 d. The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 15. Significance analysis was based on one-way ANOVA along with Bonferroni correction at a significance level of 0.01. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate a significant difference.

(E) HLS1 transcript levels of seedlings in (D). HLS1 levels were detected and normalized to PP2AA3. The mock treatment control was designated as the calibrator and set to a value of 1. The values shown indicate means of biologically repeated experiments (using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions) with sd; n ≥ 3. R represents the Pearson’s correlation coefficients of hook angles in (D) and HLS1 levels in (E), with significance of P.

(F) and (G) Transient DLR assays illustrated the negative effect of MYC2 on PIF4-induced HLS1 (F) and PIL1 (G) transcription. Reporter and effector plasmids were combined as indicated and transformed into phyA phyB protoplasts. The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 3. Statistical significance was calculated between the various effectors using two-tailed Student’s t test with asterisks denoting statistical significance (***P < 0.001; *0.01 < P < 0.05).

(H) PIL1 transcript levels of 3-d-old seedlings grown on MS or JA medium. The values shown indicate means of biologically repeated experiments (using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions) with sd; n ≥ 3.

(I) PIL1 transcript levels of seedlings grown on MS medium for 3 d and transiently treated with different concentrations of JA for 1 h. PIL1 levels were detected and normalized to PP2AA3. The zero JA treatment control was designated as the calibrator and set to a value of 1. Keys show the gradient concentration of JA (µM). The values shown indicate means of biologically repeated experiments (using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions) with sd; n ≥ 3. Statistical significance in (C), (E), (H), and (I) was calculated between noted samples using two-tailed Student’s t test with asterisks denoting statistical significance (***P < 0.001; **0.001 < P < 0.01). n.s., not significant.

The transcription factor MYC2 mediates multiple JA responses and interacts with EIN3/EIL1 to repress its function (Song et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). Protoplasts from phyA phyB seedlings, in which PIF degradation is severely compromised, were used to investigate the effect of MYC2 on PIF4 function. Using the HLS1 and PIL1 promoters as individual targets, the addition of PIF4 by transformation of an effector construct induced both HLS1 and PIL1 expression (Figures 5F and 5G), while the addition of MYC2 suppressed the induction by PIF4. Moreover, the expression level of PIL1, a target gene that reflects the transcriptional activity of PIFs, was decreased by JA treatment. This decrease was dependent on PIFs and partially dependent on MYC2 but not EIN3/EIL1 (Figures 5H and 5I). These findings indicate that JA treatment inhibits hook formation by repressing the function of PIFs in addition to EIN3 and EIL1, and the effect is likely mediated by MYC2.

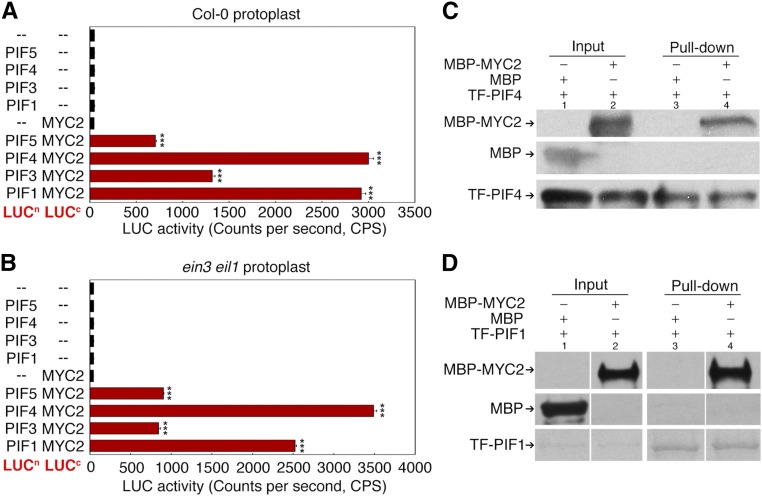

PIFs Interact with MYC2

Given that MYC2 interacts with and represses EIN3, we also investigated whether MYC2 associates with PIFs. Luciferase protein fusion constructs were generated, with the four PIFs fused to the luciferase N terminus (LUCn) and MYC2 fused to the luciferase C terminus (LUCc). For the analysis, the LUCc fusion construct and one of the LUCn fusions were cotransformed into Col-0 protoplasts, and LUC activity was quantified for each combination. Compared with the nonfusion controls, the combination of PIFs and MYC2 resulted in high LUC activity, particularly with PIF4 (Figure 6A). High LUC activity was also detected when the PIF and MYC2 fusion constructs were cotransformed into ein3 eil1 protoplasts (Figure 6B). Thus, PIFs interact with MYC2 in a manner independent of EIN3 and EIL1. In vitro pull-down assays further revealed that MYC2 directly binds to PIF1 and PIF4 (Figures 6C and 6D). Interestingly, beyond the repression of PIF activity by MYC2, the PIF4 protein level was also downregulated by JA (Supplemental Figure 5). Therefore, it is conceivable that JA represses both PIF abundance and activity to negatively impact hook development, a scenario similar to the regulation of EIN3 and EIL1.

Figure 6.

MYC2 Interacts with PIFs.

(A) and (B) Firefly luciferase complementation assays showing the in vivo interaction between MYC2 and PIFs. MYC2-LUCc was combined with the indicated PIF-LUCn plasmids and transformed into Col-0 (A) or ein3 eil1 (B) protoplasts. “–” indicates the LUCn or LUCc control plasmids. LUC activity was recorded after the samples were incubated for 12 to 16 h and mixed with luciferin. Statistical significance was calculated to compare the different PIF + MYC2 combinations with the LUCc + LUCn control using a Student’s t test with asterisks denoting statistical significance (***P < 0.001).

(C) and (D) Pull-down assays showing the in vitro interaction between MYC2 and PIF4 (C) as well as MYC2 and PIF1 (D). TF-PIF4 (PIF4 fused with HIS-tagged trigger factor) and TF-PIF1 were immobilized with Ni-NTA agarose then combined with MBP fusion proteins. After rounds of washing and centrifugation, the precipitated products were subjected to SDS-PAGE and further stained by Coomassie blue or blotted with the respective antibodies. Arrows indicate the corresponding proteins. For consistency, the sample order in (D) was rearranged by assigning two input samples together (lanes 1 and 2) and two pull-down samples together (lanes 3 and 4), in which the original order was lane 1-3-2-4.

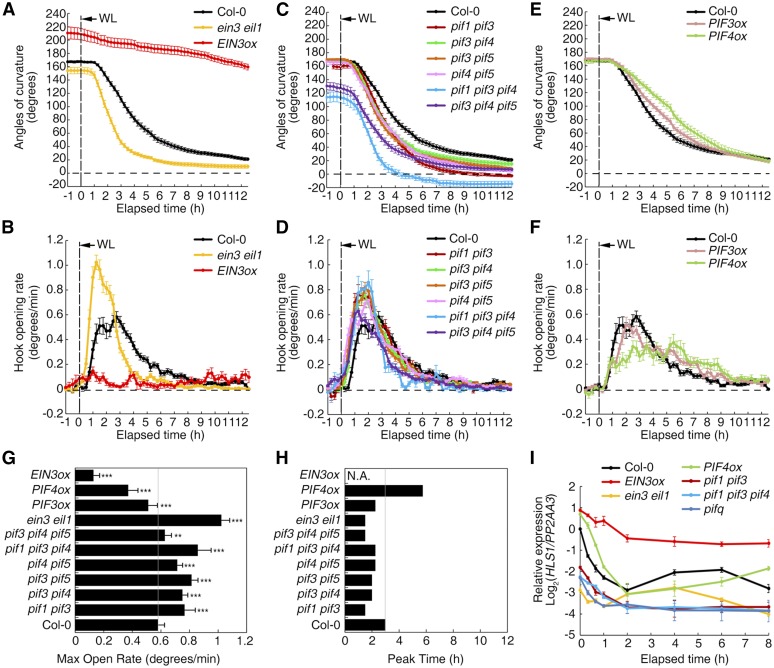

PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 Mediate Light-Induced Hook Opening

In addition to the abovementioned phytohormones, light is also a vital signal for hook development, as the preformed hook of etiolated seedlings rapidly opens when exposed to light. To better understand the mechanism underlying light-induced hook opening, a real-time imaging system (referred to as RT-Image V1 in Methods) was used to dynamically record the changes in hook angle for various mutants and transgenic plants. For Col-0 seedlings, the preformed hook curvature started to open after 2 h of light exposure, and a nearly hookless state was reached after 10 h (Supplemental Figure 6A). To better quantify this dynamic process and allow comparison of the results from different backgrounds, real-time changes in hook angle and the dynamic opening rate (i.e., change between every two time points) were calculated (Supplemental Figures 6B and 6C). Three parameters were considered: initial angle before light exposure (starting angle), maximum opening rate during the opening process (max open rate), and time required to reach the max open rate (peak time). In general, the max open rate and peak time are indicative of how quickly the preformed hook is opened by light. Compared with Col-0, ein3 eil1 exhibited faster opening after light exposure, with a higher max open rate and earlier peak time, while hook opening was delayed in transgenic plants overexpressing EIN3 (EIN3ox), as indicated by a lower max open rate and not detectable peak time (Figures 7A, 7B, 7G, and 7H). Similarly, pif mutations resulted in faster opening, based on a higher max open rate and/or earlier peak time, and opening was faster in higher order pif mutants (Figures 7C, 7D, 7G, and 7H). Conversely, PIF3ox and PIF4ox exhibited mild resistance to light-induced hook opening, as indicated by a lower max open rate and/or later peak time (Figures 7E to 7H). Due to the nearly hookless phenotype and gravitropic disorder of pifq mutants, the imaging system failed to monitor the hook opening phenotype of pifq.

Figure 7.

EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs Delay Light-Induced Hook Opening and HLS1 Decrease.

(A), (C), and (E) Real-time changes in hook angle upon light exposure. The values shown indicated means ± se; n ≥ 15.

(B), (D), and (F) Real-time changes in the hook opening rate upon light exposure. The values shown indicated means ± se; n ≥ 15.

(G) Quantified max open rates of the seedlings in (B), (D), and (F). Statistical significance was calculated between different genotypes and Col-0 using two-tailed Student’s t test with asterisks denoting statistical significance (***P < 0.001; **0.001 < P < 0.01).

(H) Peak time to reach max open rate (hours after light exposure). N.A., not available.

(I) HLS1 transcript levels rapidly decreased upon light irradiation. Seedlings were exposed to light for the indicated amounts of time after growth on MS medium for 2.5 d. HLS1 levels were detected and normalized to PP2AA3. Col-0 at the 0 h time point was designated as the calibrator and set to a value of 1, and then the y axis was rescaled to log2 values respectively. The values shown indicate means of biologically repeated experiments (using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions) with sd; n = 3.

Consistent with the decrease in hook angle under light exposure, HLS1 expression was also downregulated (Figure 7I) along with PIL1 and EBF2 expression (Supplemental Figures 6D and 6E). Although the observed change in HLS1 expression was greater in Col-0 than in the ein3 eil1 and pif mutants upon light exposure, the absolute expression level of HLS1 reached its minimum more rapidly in the mutants (Figure 7I). In EIN3ox, HLS1 expression remained much higher than that in Col-0 after light exposure, consistent with the finding that EIN3ox was highly resistant to light-induced hook opening (Figure 7A).

Other studies have shown that both PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 can be degraded in response to light. PIFs are degraded in a very short amount of time (within minutes), while EIN3 and EIL1 are degraded much more slowly (Leivar and Quail, 2011; Shi et al., 2016). This is consistent with our findings that the light-induced PIL1 decline was faster than the EBF2 decline (Supplemental Figures 6D and 6E). Considering these results in aggregate, we propose that light induces hook opening and represses HLS1 expression via the removal of PIFs and EIN3/EIL1, with PIFs mediating the fast response and EIN3/EIL1 mediating the slow response.

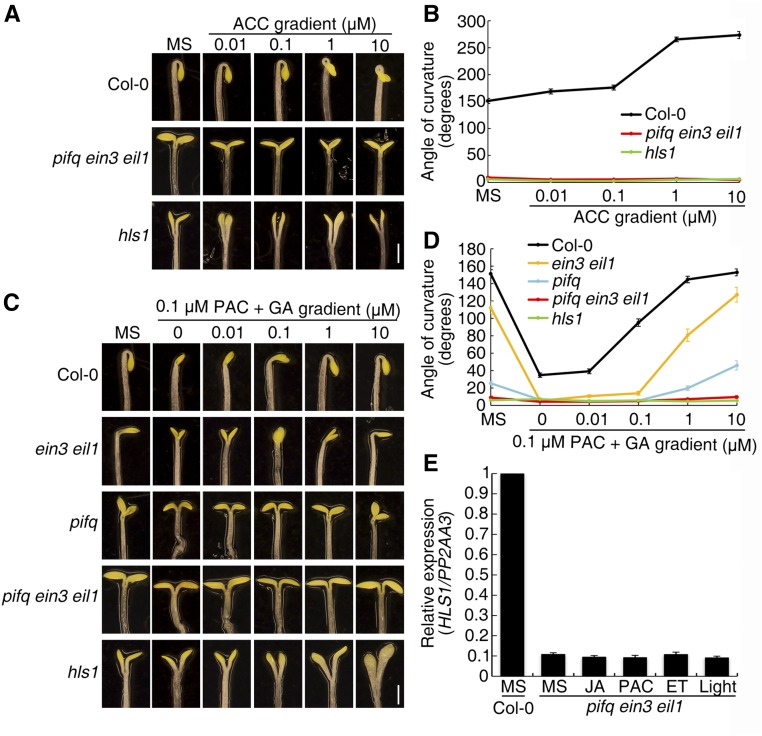

The pifq ein3 eil1 Sextuple Mutant Is Not Responsive to Multiple Hook-Modulating Signals

In light of the parallel roles of EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs in apical hook regulation, we next investigated whether EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs integrate internal and external signals to fine-tune hook development. Specifically, we observed the hook response of pifq ein3 eil1 to multiple hormones and light signals. As with hls1, pifq ein3 eil1 did not respond to a gradient of ACC (Figures 8A and 8B), nor to a gradient of Ag+, which blocks ethylene perception (Supplemental Figures 7A and 7B). GA treatment restored the hook curvature defect induced by PAC in Col-0, ein3 eil1, and pifq. However, GA treatment did not result in any change of pifq ein3 eil1 hook curvature (Figures 8C and 8D). Similarly, neither JA treatment nor light exposure caused changes of pifq ein3 eil1 hook curvature (Supplemental Figures 7C to 7E). Because of the gravitropic disorder of pifq ein3 eil1, the RT-Image V1 system failed to capture the hook change in pifq ein3 eil1, as it was occasionally out of the viewing field. Instead of monitoring the individual hook region, we recorded the whole Petri dish for a larger field of view in the updated version of the real-time imaging system (referred to as RT-Image V2 in Methods). The opening processes in Col-0, ein3 eil1, pif mutants, and EIN3ox were similar with the previous results, wherein the ein3 eil1 and pif mutants opened faster, while EIN3ox and ctr1 mutant had a much slower opening process (Supplemental Figure 7E). The change in hook angle was simultaneously recorded for pifq, and it exhibited a fast opening upon light exposure (Supplemental Figure 7E). In addition to the hook phenotype, HLS1 expression in pifq ein3 eil1 was barely affected by multiple treatments, including phytohormones and light (Figure 8E).

Figure 8.

The pifq ein3 eil1 Sextuple Mutant Exhibits Insensitivity to Multiple Hormones and Light.

(A) and (C) Three-day-old etiolated seedlings were grown on ACC gradient (A) or PAC with/without GA gradient (B) medium, and the hook phenotype was recorded. Bar = 1 mm.

(B) and (D) Quantification of the hook curvature phenotype in (A) and (C), respectively. The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 15.

(E) HLS1 transcript levels in pifq ein3 eil1 seedlings after growth on MS, 1 μM JA, or 1 μM PAC medium for 3 d or after transient treatment with 10 ppm ethylene or white light for 1 h. The HLS1 levels were normalized to PP2AA3 and calibrated to the transcript levels in Col-0 (set to a value of 1). The values shown indicate means of biologically repeated experiments (using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions) with sd; n ≥ 3.

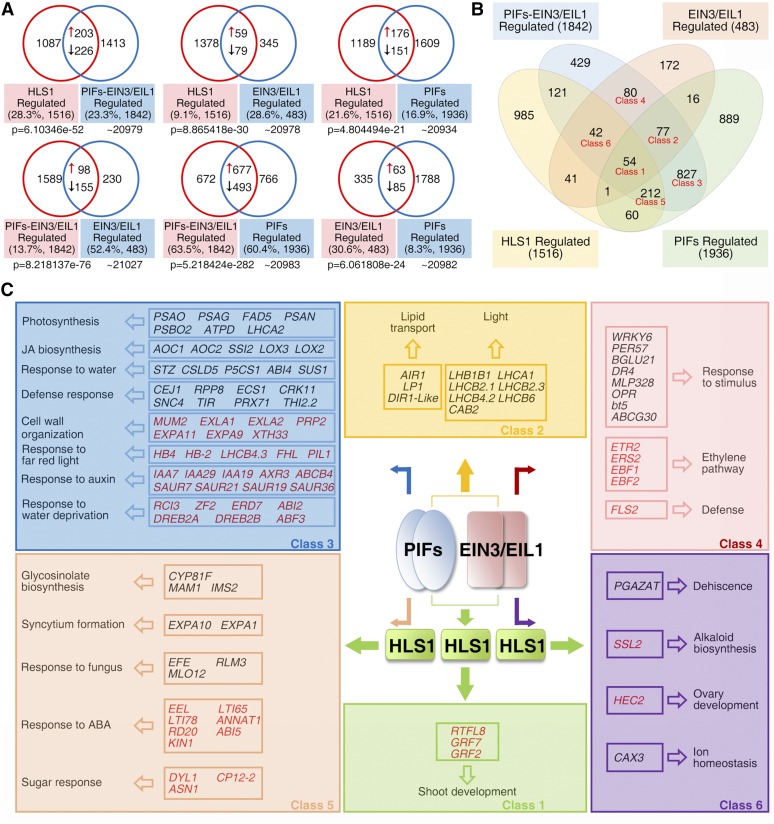

PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 Additively and Distinctly Regulate Myriad Biological Processes

To further explore the relationship between PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 in hook development regulation, transcriptome profiles from 3-d-old etiolated seedlings (Col-0, hls1, ein3 eil1, pifq, and pifq ein3 eil1) were sequenced and analyzed. Differentially expressed genes in hls1, ein3 eil1, pifq, and pifq ein3 eil1 versus Col-0 were designated as HLS1-, EIN3/EIL1-, PIF-, and PIF-EIN3/EIL1-regulated gene sets, respectively (listed in Supplemental Data Set 1). Pairwise comparison revealed significant overlap between all set pairs (Figure 9A; P < 0.001). For instance, 23.3% of genes affected in the PIF-EIN3/EIL1 set were also regulated by HLS1, while 28.3% of genes affected in the HLS1 set were regulated by PIF-EIN3/EIL1 (Figure 9A). Interestingly, 30.6% of EIN3/EIL1-regulated genes (148 out of 483) were also PIF regulated, but only 8.3% of PIF-regulated genes (148 out of 1936) were regulated by EIN3 and EIL1 (Figure 9A). This disparity indicates that more genes are regulated by PIFs (1936) in etiolated seedlings than by EIN3 and EIL1 (483) and that there are separate processes regulated either by PIFs or EIN3 and EIL1. The numbers of shared genes among these four sets were summarized using a Venn diagram, in which the genes were classified according to their expression patterns (Figure 9B; Supplemental Figures 8A and 8B). Six classes were highlighted and genes in the following classes were identified in the gene sets listed in parentheses: Class 1 (genes identified as PIF-, EIN3/EIL1-, PIF-EIN3/EIL1-, and HLS1-regulated), Class 2 (genes identified as PIF-, EIN3/EIL1-, and PIF-EIN3/EIL1-regulated), Class 3 (genes identified as PIF- and PIF-EIN3/EIL1-regulated), Class 4 (genes identified as EIN3/EIL1- and PIF-EIN3/EIL1-regulated), Class 5 (genes identified as PIF-, PIF-EIN3/EIL1-, and HLS1-regulated), and Class 6 (genes identified as EIN3/EIL1-, PIF-EIN3/EIL1-, and HLS1-regulated).

Figure 9.

PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 Additively and Distinctly Regulate Myriad Biological Processes.

(A) Venn diagrams showing the pairwise overlap between the HLS1-, PIF-EIN3/EIL1-, EIN3/EIL1-, and PIF-regulated gene sets. “↑” represents activated genes that show decreased transcript levels in both mutants (compared with Col-0); “↓” represents repressed genes that show elevated transcript levels in both mutants (compared with Col-0). Genes showing opposite changes of expression in two compared mutants were excluded from the overlap. Percentage values indicate the percentage of overlapping genes among total regulated genes. P values were calculated using the hypergeometric distribution.

(B) Venn diagram showing the overlaps among the HLS1-, PIF-EIN3/EIL1-, EIN3/EIL1-, and PIF-regulated gene sets. Genes sharing accordant transcriptional pattern among mutants were counted as overlaps. Classes 1 to 6 were selected for the GO enrichment analysis in (C).

(C) Summary of action for EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs, which function as a transcriptional couple in the regulation of HLS1 and other downstream genes in diverse processes. Representative genes with known functions in various biological processes are listed. Repressed and activated genes (thus, up- and downregulated in corresponding mutants) are shown in black and red, respectively.

For each class, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) analysis together with functional clustering using BiNGO in the Cytoscape software package and summarized the action mode of EIN3/EIL1-PIFs in Figure 9C. Class 1 genes were preferentially associated with shoot development, which might contribute to the differential growth of hypocotyls. Class 2 genes were associated with lipid transport and light response functions, indicating cooperation between PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 for various biological processes other than hook development. At the same time, the expression of many genes was specifically regulated either by PIFs or by EIN3/EIL1, and these genes were classified into different categories associated with multiple biological processes (Figure 9C; Classes 3–6). Class 3 genes were associated with photosynthesis and cell wall organization, whereas Class 4 genes were associated with the ethylene pathway and stimulus/defense response. Class 5 and 6 genes clustered into separate processes, suggesting the existence of PIF-HLS1 and EIN3/EIL1-HLS1 regulatory pathways. Taken together, these results indicate that PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 additively function as a transcriptional couple in some processes but also function separately from each other in other diverse processes.

DISCUSSION

The apical hook of dark-grown dicotyledonous seedlings is essential for protecting the apical meristematic tissues and cotyledons when seedlings protrude through the soil. In Arabidopsis, hook development is well characterized as a differential growth process: A laterally asymmetric distribution of auxin within the hypocotyl apical region establishes hook formation, and it is modulated by various internal and external signals. Among these signals, ET and GA are positive regulators, whereas JA and light negatively regulate hook formation. Previous studies identified the HLS1 gene as an indispensable hook formation factor whose mutation causes a hookless phenotype. HLS1 was further found to be a direct target gene of EIN3 and EIL1, two master transcription factors in ET signaling. The synergism between ET and GA, as well as the antagonism between ET and JA, converges on EIN3 and EIL1 by affecting either their abundance or activity, which subsequently impacts HLS1 expression.

In this study, we present several lines of evidence showing that PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 are two types of transcription factors that independently activate HLS1 transcription and integrate multiple upstream signals to regulate hook development (Supplemental Figure 8C). First, the compromised hook curvature of ein3 eil1 was further inhibited by the GA biosynthesis inhibitor PAC and JA treatment, hinting at the involvement of additional transcription factors in response to PAC and JA. Second, PIFs were found to function redundantly in maintaining hook formation in etiolated Arabidopsis seedlings. Loss of PIF1/3/4/5 led to reduced hook curvature and HLS1 expression, and the more severe phenotypes were generally observed in higher order pif mutants. Inducing individual PIF genes in pifq, which exhibits a largely hookless phenotype, restored hook formation and HLS1 expression. Third, PIF4 was found to activate HLS1 transcription by directly binding to an E-box motif in the HLS1 promoter. EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs alone were capable of activating HLS1 expression and promoting hook curvature, indicative of independent modes of action. Fourth, JA inhibited PIF function partly through the action of MYC2, which can physically interact with PIFs. Finally, the pifq ein3 eil1 sextuple mutant exhibited a completely hookless phenotype and marginal HLS1 expression, both of which were irresponsive to all of the signals examined, including ET, GA, JA, and light. Together with the previous findings that JA-activated MYC2 represses EIN3 function (Song et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014), that light promotes the degradation of EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs (Leivar and Quail, 2011; Shi et al., 2016), and that DELLA proteins inhibit EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs while ethylene stabilizes them (Guo and Ecker, 2003; de Lucas et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2008; An et al., 2010; Li et al., 2016; Dong et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2017), we propose that PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 function as a transcriptional couple in regulating hook development. Moreover, their abundance and/or activity are similarly regulated by multiple hook-modulating hormones and light.

All four PIFs analyzed in our study positively regulated hook development, but they may nevertheless have distinct contributions or mechanisms. For instance, PIF3 had a relatively low capacity to promote hook curvature and HLS1 expression upon induction in iPIF3/pifq ein3 eil1. Probably due to the dominant role of PIF1 in repressing seed germination (Oh et al., 2004), we can hardly observe a pronounced effect of PIF1 induction on hook formation in iPIF1/pifq ein3 eil1 seedlings. Although both PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 are required for proper hook development, pifq seedlings had a more greatly reduced hook curvature compared with ein3 eil1, further underscoring the differences between PIFs and EIN3/EIL1. One possible explanation for their distinct activities is that PIFs, as essential skotomorphogenic components, typically accumulate at relatively high levels in etiolated seedlings (Leivar and Quail, 2011), whereas EIN3 and EIL1 are stress-responsive proteins with limited abundance at the resting state (Guo and Ecker, 2003). Consistent with this, there are more transcriptionally altered genes in etiolated pifq seedlings than in ein3 eil1. As such, the abundance and activity of PIFs in darkness may provide a suitable target for the removal or opening of hook curvature by negative signals, such as light and JA. Conversely, the limited abundance of EIN3 and EIL1 may help guarantee an efficient response to positive signals, such as ET, whose production is triggered during emergence, and GA, which is abundant during germination. The similar but distinct regulatory patterns of PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 (in terms of kinetics and extent) by these signals further stress the additive yet independent roles of these core transcription factors in the control of hook development.

The HLS1 gene is an essential regulator of hook formation, and the hls1 mutant remains hookless when treated with ET or GA (An et al., 2012). Previous studies together with this study have showed the positive correlation between HLS1 transcript levels and hook angles, illustrating the important role of HLS1 transcriptional regulation in hook development. However, the hook curvature of hls1 arf2 seedlings is slightly exaggerated by ET (Li et al., 2004), suggesting the existence of a HLS1-independent pathway. Consistently, ET has been reported to modulate auxin response and transport through AUX1/LAX3 and PINs (Vandenbussche et al., 2010; Zádníková et al., 2010). By inducing PIF4 in iPIF4/hls1 transgenic plants, we found that PIF4 overexpression was able to restore hook formation in the hls1 mutant to a limited degree (Supplemental Figure 2), supporting the existence of a HLS1-independent pathway for PIF4-promoted hook development. This is further supported by the findings that PIFs can directly regulate auxin biosynthesis and signaling (Hornitschek et al., 2012). It was recently shown that PIF5-targeted decrease of PILS expression mediates the hook opening process (Béziat et al., 2017). We also found that PIF-regulated genes (Class 3; Figure 9C) were associated with auxin response. Thus, EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs may promote hook formation via both HLS1-dependent and HLS1-independent pathways.

Through mRNA sequencing analysis, our studies reveal that EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs regulate gene expression and biological processes both additively and separately (Figure 9C; Supplemental Figure 8C). From the analysis, 30.6% of EIN3/EIL1-regulated genes were also affected by PIFs (Classes 1 and 2; Figure 9B), and these genes were functionally associated with shoot development, lipid transport, and light response (Supplemental Figure 8C). Among these, genes associated with shoot development, which could potentially contribute to differential growth of the hypocotyl, were coregulated by HLS1 (Class 1). For EIN3/EIL1-regulated genes, the associated processes included ethylene response (Class 4) and dehiscence (Class 6); for PIF-regulated genes, the functional analysis identified photosynthesis (Class 3) and glycosinolate biosynthesis (Class 5). Taken together, our data show how PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 function as a transcriptional couple to integrate multiple upstream signals and regulate myriad biological processes both additively and distinctly.

METHODS

Plant Materials, Genetic Manipulation, and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ein3-1 eil1-1 (Alonso et al., 2003), pif1 (SALK_131872C) (Penfield et al., 2005), pif3 (SALK_081927C) (Zhong et al., 2010), pif4 (SALK_140393C) (Zhong et al., 2012), pif5 (SALK_087012C) (Fujimori et al., 2004), pif1 pif3 (Zhong et al., 2010), pif3-3 pif4-2 (Leivar et al., 2008), pif3 pif5-3, pif4-2 pif5, pif1-1 pif3-3 pif4-2 (Leivar et al., 2008), pif1 pif3 pif5, pif3-3 pif4-2 pif5 (Leivar et al., 2008), pif1 pif3 pif4 pif5 (pifq) (Zhong et al., 2012), myc2-2 (Lorenzo et al., 2004), hls1-1 (Guzmán and Ecker, 1990), phyA-211 phyB-9 (Strasser et al., 2010), EIN3ox (Chao et al., 1997), PIF3ox (Kim et al., 2003), and PIF4ox (Oh et al., 2012) were lab stock. The pifq ein3 eil1 sextuple mutants were generated by crossing pifq and ein3 eil1, followed by PCR-based genotyping of the F2 population. pER8:PIF3/4/5-MYC/pifq ein3 eil1 (iPIF/pifq ein3 eil1) transgenic plants were obtained by cloning PIF3/4/5 coding sequences into the pER8 vector and transforming the constructs into the pifq ein3 eil1 background. Homozygotes were characterized by hygromycin resistance in the T2 population. Between two individual iPIF4/pifq ein3 eil1 lines, the PIF4 expression level was greater in the #6-2 line than in the #20-1 line. pER8:PIF4-MYC/hls1-1 (iPIF4/hls1) plants were obtained by transforming the PIF4/pER8 construct into the hls1-1 background, and the homozygotes were characterized by hygromycin resistance in the T2 population. pER8:PIF3/4/5-MYC/pifq (iPIF/pifq) transgenic plants were obtained by crossing each iPIF/pifq ein3 eil1 line with pifq, and the homozygotes were characterized by PCR-based genotyping of the F2 population.

Seeds were surface-sterilized with 75% ethanol and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min and washed with 100% ethanol once. The air-dried seeds were subsequently placed on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (4.4 g/L MS salt, 1% sucrose, pH 5.7, and 0.8% agar) with or without the indicated treatment. After imbibition for 3 d at 4°C with or without the indicated treatment to stimulate germination, the samples were maintained in darkness at 22°C for another 2.5 to 3 d before recording the hook phenotype or detecting gene transcript levels.

Solution Preparation

ACC, methyl jasmonate (MeJA), PAC, GA3, β-estrogen, and AgNO3 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. ACC and AgNO3 were dissolved in water to prepare 10 mM stock solution; MeJA, PAC, and GA3 were dissolved in absolute ethanol to prepare 100 mM stock solution; and β-estrogen was dissolved in DMSO to prepare 5 mM stock solution. For mock treatment, ethanol or DMSO was diluted in liquid MS or MS medium at the same fold dilution, respectively. In all of our analyses, MeJA and GA3 were used for the JA and GA treatment, respectively.

Hook Curvature Measurement and Real-Time Imaging System

Images of individual hooks were acquired using a Canon camera with a macro lens, and hook angles were measured using the ImageJ program (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). The bending angles were measured as described in the literature (Vandenbussche et al., 2010). The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 15.

Seedlings for RT-Image V1 were sown on MS medium containing 1.5% agar. After growth for 2.5 d in darkness with the plates vertically positioned, the plates were exposed to light, and individual hook images were taken every 15 min by a commercial seedling phenotyping platform (Dynaplant; http://www.yph-bio.com/DynaPlant.asp). Hook angles were measured using MATLAB. Hook opening rate (degrees/min) was determined by dividing the change in angle (between the previous time point and the current time point) by 15 min. The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 15.

Seedlings for RT-Image V2 were grown using similar conditions, but the whole Petri dish was imaged every 30 min instead of imaging the hook region of individual seedlings. Hook angles were measured using the ImageJ program, and the values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 15.

Statistical Analysis

For multiple comparison, significance analysis was performed as pairwise comparison based on one-way ANOVA along with Bonferroni correction at a significance level of 0.01, and IBM SPSS Statistics software was used for the analysis. Different lowercase letters above the bars in each histogram indicate a significant difference. An ANOVA table is provided in Supplemental Data Set 2.

For others, statistical significance was calculated between two noted samples using two-tailed Student’s t test. Asterisks denoted statistical significance test (***P < 0.001; **0.001 < P < 0.01; *0.01 < P < 0.05).

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between hook angles and HLS1 transcription levels were calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics software with default parameters. R represented the correlation coefficients and P represented the significance.

Protein Extraction and Immunoblotting

Whole seedlings were finely ground in liquid nitrogen and suspended thoroughly in protein extraction buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 25% glycerol, 2% SDS, 14.4 M β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% bromophenol, and 1 M DTT) by vortexing. Proteins were extracted by boiling for 10 min at 100°C and then roughly separated via centrifugation (13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C). Supernatants were loaded onto 10% SDS-PAGE gels, and the proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose filter membrane (Millipore) according to a standard protocol. Anti-MYC (ABclonal) and anti-EIN3 (Guo and Ecker, 2003) were diluted 5000-fold for incubation with the membranes. Goat anti-mouse (or anti-rabbit) HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Promega) was diluted 7500-fold.

RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from whole etiolated seedlings using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Total RNA was subjected to reverse transcription at 42°C for 1 h with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). The oligo sequences for each of the detected genes are listed in Supplemental Data Set 2. Real-time PCR was performed on a Light Cycler 480 system (Roche) with SYBR Premix Ex Taq reagent (TaKaRa). Each experiment was performed at least three times using different pools of seedlings under noted conditions, and the values shown indicated means of repeated experiments with sd; n ≥ 3.

Protein Expression and Purification

The coding sequences of PIF1, PIF4, and PIF4 201-430aa (bHLH domain of PIF4, abbreviated as PIF4C) were cloned into the pCold-TF vector (GE Healthcare) for TF fusion (HIS-tagged trigger factor) and transformed into Transette (DE3) competent cells (TransGen). Protein expression was induced by 0.1 mM IPTG at 16°C, and proteins were purified with Ni-NTA Agarose (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. MBP-MYC2 and MBP protein were expressed and purified as previously described (Chen et al., 2011).

EMSA

Oligonucleotide probes for HLS1 were synthesized, and the annealed double-stranded DNA was labeled with digoxigenin (DIG). EMSA was performed according to the instructions for DIG Gel Shift Kit 2nd Generation (Roche). Briefly, 16 fmol of labeled probes were incubated in 1× binding buffer, 0.1 μg poly l-lysine, and 0.1 μg poly (dA·dT) with or without proteins at 22°C for 20 to 60 min. For nonlabeled probe (cold/mutant cold probe) competition, 4 pmol of cold/mutant cold probe was added to the reactions.

ChIP-PCR

ChIP-PCR was performed according to methods described in the literature (Gendrel et al., 2005) with minor modifications. Seedlings were grown on 5 μM β-estrogen medium for 3 d in darkness and then whole seedlings from four different genotypes were subjected to same procedures, in which pifq seedlings were used as negative controls (set to a value of 1) for iPIF4/pifq while pifq ein3 eil1 seedlings were used as negative controls (set to a value of 1) for iPIF4/pifq ein3 eil1. Two grams of etiolated seedlings were cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde followed by chromatin isolation. Anti-MYC antibodies (ABclonal) were added to the sonicated chromatin followed by incubation overnight to precipitate bound DNA fragments. After immobilization using Recombinant Protein G-Sepharose 4B (Invitrogen), bound DNA was eluted and amplified with primers corresponding to sequences in the HLS1 promoter. The primers are listed in Supplemental Data Set 2. Each experiment was performed three times using different pools of seedlings and the values shown indicate means of repeated experiments with sd; n = 3

Pull-Down Assay

The in vitro purified TF-PIF1 (PIF1 fused with HIS-tagged trigger factor) and TF-PIF4 were incubated with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) in pull-down buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail) for 4 h at 4°C. MBP fusion proteins were added and incubated for another 3 h at 4°C. After five washes with pull-down buffer, the precipitated resins were collected by brief centrifugation then treated with protein extraction buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected with anti-MBP (NEB) or anti-HIS (Tiangen).

Firefly Luciferase Complementation Assay

The coding sequences of PIF1/3/4/5 were inserted into the multiple cloning site of pCAMBIA1300-nLUC (Chen et al., 2008). MYC2-LUCc was described previously (Zhang et al., 2014). Plasmids were extracted and purified using Plasmid Maxiprep kits (Vigorous).

Arabidopsis protoplasts were prepared from 10-d-old green seedlings or 4-week-old adult seedlings following a standard protocol. For the assay, 10 μg of each construct (one LUCn construct and one LUCc construct) was cotransformed into protoplasts and incubated for 12 to 16 h in darkness. After the incubation period, luciferin (Gold Biotechnology) was added, and luciferase activity was recorded on an LB 985 NightSHADE system (Berthold Technologies).

DLR System

ProHLS1_WT:LUC was constructed by amplifying 1.5 kb of the Arabidopsis HLS1 promoter and inserting it into the pGreen II 0800-LUC vector (Hellens et al., 2005). Mutated/deleted versions of the HLS1 promoter were amplified using KOD polymerase (Toyobo), site-specific mutated/deleted primers, and ProHLS1_WT:LUC as template. The fragments were digested with DpnI and subsequently treated with T4 ligase. The ProPIL1:LUC plasmid was described previously (Zhang et al., 2013).

The coding sequences of EIN3 and MYC2 were amplified and inserted into pCAMBIA1300-nLUC (Chen et al., 2008). EIN3-LUCn, PIF4-LUCn, and MYC2-LUCn were used as effectors.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 carrying the reporter plasmid (ProHLS1:LUC) and specific effector plasmids (empty vector, EIN3, or PIF4) were cultured to OD600 = 0.15 and OD600 = 0.15/0.3/0.45 for 1×/2×/3×, respectively. The reporter and effector were combined at equal volumes, maintained at room temperature without shaking for 3 h, infiltrated into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves, and incubated for another 3 d.

Protoplasts from pifq ein3 eil1 or phyA phyB seedlings and maxiprep plasmids were prepared as described above. For the assay, 3 μg reporter plasmid and 9 μg effector plasmid (empty vector, EIN3, PIF4, MYC2, or PIF4 + MYC2) were cotransformed into protoplasts and incubated for 12 to 16 h in darkness.

The DLR system (Promega) was used for transient expression analysis in N. benthamiana leaves and Arabidopsis protoplasts. The activities of firefly (Photinus pyralis) and Renilla reniformis luciferases (LUC and REN, respectively) were sequentially measured from a single sample on a GLO-MAX 20/20 luminometer (Promega). The ratio of LUC/REN was calculated as an indicator of the final transcriptional activity. The values shown indicate means ± se; n ≥ 3.

RNA Sequencing

Three-day-old etiolated seedlings of Col-0, hls1, pifq, ein3 eil1, and pifq ein3 eil1 plants (not including roots) were collected and ground into a fine powder in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen). The RNA sequencing and differential gene expression analysis were performed at the Bionova Company. RNA quality was evaluated on a Bioanalyzer 2100 instrument (Agilent). Sequencing libraries were prepared following the protocol for the Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (NEB), and 150-nucleotide paired-end high-throughput sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten system. Low quality sequencing reads were removed. Clean reads were mapped to the Arabidopsis reference genome (TAIR10; www.arabidopsis.org) with Tophat2 (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml) software, and differentially expressed genes were identified using cuffdiff (http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/cuffdiff/) based on a fold change > 2 and q-value < 0.05 between the case group sample and the control group sample. Venn diagrams were generated based on elevated transcripts in all four mutants compared with Col-0 (defined as genes repressed by HLS1 and/or transcription factors) or decreased transcripts in all four (defined as genes activated by HLS1 and/or transcription factors) separately using VENNY 2.1 (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html). The numbers in Figures 9A and 9B, except the ones labeled by arrows, were calculated by adding the amount of elevated and decreased transcripts, based on the specific category. P values were calculated using the hypergeometric distribution (Zhou et al., 2007). GO enrichment analysis was performed using BiNGO (https://www.psb.ugent.be/cbd/papers) in the Cytoscape software package (http://cytoscape.org). Activated genes and repressed genes were tested separately as well. Default parameters were used for all analyses performed using the bioinformatics software.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative or GenBank/EMBL databases. The accession numbers are listed in Supplemental Table 2. Raw data for the RNA-sequencing are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession number GSE116802.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. PIF4-promoted hook development partially depends on HLS1.

Supplemental Figure 2. PIFs promote HLS1 expression.

Supplemental Figure 3. EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs promote hook curvature and HLS1 expression in parallel.

Supplemental Figure 4. PAC treatment inhibits the function of PIFs while ET-promoted hook development depends on EIN3/EIL1.

Supplemental Figure 5. JA promotes PIF4 degradation.

Supplemental Figure 6. Dynamic change of hook curvature and gene expression after light exposure.

Supplemental Figure 7. pifq ein3 eil1 exhibits insensitivity to multiple hormones and light.

Supplemental Figure 8. Action mode of EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs.

Supplemental Table 1. Oligo sequences used in this study.

Supplemental Table 2. Accession numbers.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Differentially expressed gene sets from mRNA sequencing.

Supplemental Data Set 2. One-way ANOVA table.

Dive Curated Terms

The following phenotypic, genotypic, and functional terms are of significance to the work described in this paper:

Acknowledgments

We thank Chuanyou Li and Jian-min Zhou from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences; Xing Wang Deng from the School of Advanced Agriculture Sciences, Peking University; and Peter H. Quail from the Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California, Berkeley, for kindly providing research materials. We also thank all members of the Guo Lab for stimulating discussions and suggestions. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 91740203 and 31570286 to H.G.), by start-up funding from Southern University of Science and Technology to H.G., and by grants from Peking-Tsinghua Center for Life Sciences to H.G.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.G. and X.Z. conceived and designed this study. X.Z. performed most of the experiments and data organization. Y.J. and H.M. performed the real-time imaging experiments. C.X. and F.A. provided several genetic materials. Y.X. constructed several plasmids for the firefly luciferase complementation assay and performed in vitro purification. P.H. and H.W. performed the phenotypic observations. X.Z. and B.L. analyzed the mRNA sequencing results. X.Z., Y.W., and H.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors analyzed the data and discussed the article.

References

- Abbas M., Alabadí D., Blázquez M.A. (2013). Differential growth at the apical hook: all roads lead to auxin. Front. Plant Sci. 4: 441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard P., Vriezen W.H., Van Der Straeten D., Harberd N.P. (2003). Ethylene regulates arabidopsis development via the modulation of DELLA protein growth repressor function. Plant Cell 15: 2816–2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J.M., Stepanova A.N., Solano R., Wisman E., Ferrari S., Ausubel F.M., Ecker J.R. (2003). Five components of the ethylene-response pathway identified in a screen for weak ethylene-insensitive mutants in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 2992–2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An F., et al. (2010). Ethylene-induced stabilization of ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 and EIN3-LIKE1 is mediated by proteasomal degradation of EIN3 binding F-box 1 and 2 that requires EIN2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22: 2384–2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An F., Zhang X., Zhu Z., Ji Y., He W., Jiang Z., Li M., Guo H. (2012). Coordinated regulation of apical hook development by gibberellins and ethylene in etiolated Arabidopsis seedlings. Cell Res. 22: 915–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béziat C., Barbez E., Feraru M.I., Lucyshyn D., Kleine-Vehn J. (2017). Light triggers PILS-dependent reduction in nuclear auxin signalling for growth transition. Nat. Plants 3: 17105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleecker A.B., Estelle M.A., Somerville C., Kende H. (1988). Insensitivity to ethylene conferred by a dominant mutation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 241: 1086–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao Q., Rothenberg M., Solano R., Roman G., Terzaghi W., Ecker J.R. (1997). Activation of the ethylene gas response pathway in Arabidopsis by the nuclear protein ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and related proteins. Cell 89: 1133–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., et al. (2011). The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor MYC2 directly represses PLETHORA expression during jasmonate-mediated modulation of the root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 3335–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zou Y., Shang Y., Lin H., Wang Y., Cai R., Tang X., Zhou J.M. (2008). Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay for protein-protein interactions in plants. Plant Physiol. 146: 368–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chini A., Fonseca S., Fernández G., Adie B., Chico J.M., Lorenzo O., García-Casado G., López-Vidriero I., Lozano F.M., Ponce M.R., Micol J.L., Solano R. (2007). The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signalling. Nature 448: 666–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lucas M., Davière J.M., Rodríguez-Falcón M., Pontin M., Iglesias-Pedraz J.M., Lorrain S., Fankhauser C., Blázquez M.A., Titarenko E., Prat S. (2008). A molecular framework for light and gibberellin control of cell elongation. Nature 451: 480–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X.W., Caspar T., Quail P.H. (1991). cop1: a regulatory locus involved in light-controlled development and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 5: 1172–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill A., Thomas S.G., Hu J., Steber C.M., Sun T.P. (2004). The Arabidopsis F-box protein SLEEPY1 targets gibberellin signaling repressors for gibberellin-induced degradation. Plant Cell 16: 1392–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrecht B., Xue G.P., Sprague S.J., Kirkegaard J.A., Ross J.J., Reid J.B., Fitt G.P., Sewelam N., Schenk P.M., Manners J.M., Kazan K. (2007). MYC2 differentially modulates diverse jasmonate-dependent functions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 2225–2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Ni W, Yu R, Deng X W, Chen H, Wei N. (2017). Light-dependent degradation of PIF3 by SCFEBF1/2 promotes a photomorphogenic response in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 27: 2420–2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker J.R. (1995). The ethylene signal transduction pathway in plants. Science 268: 667–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., et al. (2008). Coordinated regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana development by light and gibberellins. Nature 451: 475–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori T., Yamashino T., Kato T., Mizuno T. (2004). Circadian-controlled basic/helix-loop-helix factor, PIL6, implicated in light-signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 45: 1078–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendrel A.V., Lippman Z., Martienssen R., Colot V. (2005). Profiling histone modification patterns in plants using genomic tiling microarrays. Nat. Methods 2: 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Ecker J.R. (2003). Plant responses to ethylene gas are mediated by SCF(EBF1/EBF2)-dependent proteolysis of EIN3 transcription factor. Cell 115: 667–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán P., Ecker J.R. (1990). Exploiting the triple response of Arabidopsis to identify ethylene-related mutants. Plant Cell 2: 513–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpham N.V.J., Berry A.W., Knee E.M., Rovedahoyos G., Raskin I., Sanders I.O., Smith A.R., Wood C.K., Hall M.A. (1991). The effect of ethylene on the growth and development of wild-type and mutant Arabidopsis-thaliana (L). Heynh. Ann. Bot. (Lond.) 68: 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hellens R.P., Allan A.C., Friel E.N., Bolitho K., Grafton K., Templeton M.D., Karunairetnam S., Gleave A.P., Laing W.A. (2005). Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods 1: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornitschek P., Kohnen M.V., Lorrain S., Rougemont J., Ljung K., López-Vidriero I., Franco-Zorrilla J.M., Solano R., Trevisan M., Pradervand S., Xenarios I., Fankhauser C. (2012). Phytochrome interacting factors 4 and 5 control seedling growth in changing light conditions by directly controlling auxin signaling. Plant J. 71: 699–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B., Shi Y., Zhang X., Xin X., Qi L., Guo H., Li J., Yang S. (2017). PIF3 is a negative regulator of the CBF pathway and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114: E6695–E6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R., Shen Y., Marion C.M., Tsuchisaka A., Theologis A., Schäfer E., Quail P.H. (2007). The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor PIF5 acts on ethylene biosynthesis and phytochrome signaling by distinct mechanisms. Plant Cell 19: 3915–3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Yi H., Choi G., Shin B., Song P.S., Choi G. (2003). Functional characterization of phytochrome interacting factor 3 in phytochrome-mediated light signal transduction. Plant Cell 15: 2399–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi M., Yanagisawa S. (2008). Ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis involves feedback regulation via the elaborate control of EBF2 expression by EIN3. Plant J. 55: 821–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman A., Black R., Ecker J.R. (1996). HOOKLESS1, an ethylene response gene, is required for differential cell elongation in the Arabidopsis hypocotyl. Cell 85: 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P., Quail P.H. (2011). PIFs: pivotal components in a cellular signaling hub. Trends Plant Sci. 16: 19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P., Monte E., Al-Sady B., Carle C., Storer A., Alonso J.M., Ecker J.R., Quail P.H. (2008). The Arabidopsis phytochrome-interacting factor PIF7, together with PIF3 and PIF4, regulates responses to prolonged red light by modulating phyB levels. Plant Cell 20: 337–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Johnson P., Stepanova A., Alonso J.M., Ecker J.R. (2004). Convergence of signaling pathways in the control of differential cell growth in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 7: 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K., Yu R., Fan L.M., Wei N., Chen H., Deng X.W. (2016). DELLA-mediated PIF degradation contributes to coordination of light and gibberellin signalling in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 7: 11868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]