Red light induces photosynthesis-dependent phosphorylation of plasma membrane H+-ATPase in guard cells to promote stomatal opening in whole leaves.

Abstract

Stomatal opening is stimulated by red and blue light. Blue light activates plasma membrane (PM) H+-ATPase by phosphorylating its penultimate residue, threonine, via a blue light photoreceptor phototropin-mediated signaling pathway in guard cells. Blue light-activated PM H+-ATPase promotes the accumulation of osmolytes and, thus, the osmotic influx of water into guard cells, driving stomatal opening. Red light-induced stomatal opening is thought to be dependent on photosynthesis in both guard cell chloroplasts and mesophyll cells; however, how red light induces stomatal opening and whether PM H+-ATPase is involved in this process have remained unclear. In this study, we established an immunohistochemical technique to detect the phosphorylation level of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells using whole leaves of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and unexpectedly found that red light induces PM H+-ATPase phosphorylation in whole leaves. Red light-induced PM H+-ATPase phosphorylation in whole leaves was correlated with stomatal opening under red light and was inhibited by the plant hormone abscisic acid. In aha1-9, a knockout mutant of one of the major isoforms of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells, red light-dependent stomatal opening was delayed in whole leaves. Furthermore, the photosynthetic electron transport inhibitor 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea inhibited red light-induced PM H+-ATPase phosphorylation as well as red light-induced stomatal opening in whole leaves. Our results indicate that red light-induced PM H+-ATPase phosphorylation in guard cells promotes stomatal opening in whole leaves, providing insight into the photosynthetic regulation of stomatal opening.

Stomata are composed of pairs of guard cells in the plant epidermis and serve as the gate for gas exchange, controlling CO2 uptake for photosynthesis as well as water loss by transpiration. Plants respond to various environmental stimuli with changes in guard cell turgor and volume, which leads to stomatal opening or closure (Inoue and Kinoshita, 2017; Jezek and Blatt, 2017). The accumulation of K+ and/or sugars in guard cells drives the osmotic influx of water and, thus, stomatal opening. K+ accumulates through voltage-gated inward-rectifying K+ channels in response to hyperpolarization of the plasma membrane (PM) in guard cells (Inoue and Kinoshita, 2017; Jezek and Blatt, 2017). Sugars accumulate via photosynthesis and starch degradation (Daloso et al., 2016).

Stomatal opening is stimulated by light, including blue and red light (Shimazaki et al., 2007; Inoue and Kinoshita, 2017). Blue light-induced stomatal opening is mediated by blue light photoreceptor phototropins (phot1 and phot2; Kinoshita et al., 2001; Doi et al., 2004; Ando et al., 2013). Blue light activates PM H+-ATPase via phosphorylation of the penultimate C-terminal residue, Thr, even in isolated guard cell protoplasts (GCPs) or epidermal tissue (Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999, 2002; Ueno et al., 2005; Hayashi et al., 2011), which indicates that blue light-induced stomatal opening is a guard cell-autonomous reaction. In addition, blue light induces starch degradation, resulting in the accumulation of sugars in guard cells (Poffenroth et al., 1992; Talbott and Zeiger, 1993). A recent study suggested that blue light-activated PM H+-ATPase is required for this degradation (Horrer et al., 2016; for review, see Santelia and Lunn, 2017). In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), all isogenes of PM H+-ATPase (AHA1–AHA11) are expressed in guard cells (Ueno et al., 2005). Among them, AHA1 is the major isoform and is responsible for blue light-induced stomatal opening (Yamauchi et al., 2016).

Red light-induced stomatal opening is inhibited by a photosynthetic electron transport inhibitor, 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU); thus, it is considered to depend on photosynthesis (Sharkey and Raschke, 1981; Doi and Shimazaki, 2008; Wang et al., 2011; Suetsugu et al., 2014). Red light leads to the accumulation of sugars in guard cells via photosynthesis (Poffenroth et al., 1992; Talbott and Zeiger, 1993) and starch degradation (Olsen et al., 2002). In addition, guard cells import Suc synthesized in mesophyll photosynthesis from apoplasts via the activity of H+/Suc symporters in these cells (Lu et al., 1997; Daloso et al., 2016). Red light also leads to the accumulation of K+ in guard cells, and PM H+-ATPase activity in guard cells is inferred to be required for this uptake (Hsiao et al., 1973; Olsen et al., 2002); however, it is controversial whether red light activates PM H+-ATPase in guard cells. Although there is a report describing red light-induced activation of PM H+-ATPase in GCPs (Serrano et al., 1988), this finding has not been reproduced (Roelfsema et al., 2001; Taylor and Assmann, 2001). If this does occur, it remains to be revealed how red light activates PM H+-ATPase in guard cells, because PM H+-ATPase activity is regulated not only by phosphorylation of the C-terminal penultimate residue, Thr, but also by modifications at other residues in the protein (Falhof et al., 2016).

Guard cells respond to intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) rather than ambient CO2 (Mott, 1988). Illumination of guard cells with a small beam of red light does not induce a change in PM potential (Roelfsema et al., 2001). Such localized light illumination is insufficient for stomatal opening (Mott et al., 2008). A high concentration of CO2 activates anion channels and depolarizes the PM of guard cells, while illumination of a large area of a leaf with red light decreases substomatal CO2 concentration (Roelfsema et al., 2002). Elevated CO2 also inactivates and activates inward- and outward-rectifying K+ currents, respectively (Brearley et al., 1997). These reports suggest that red light-induced stomatal opening may be an indirect response to the reduction of Ci by photosynthesis. In fact, a low concentration of CO2 also induces stomatal opening mediated by low CO2 signaling components, HIGH LEAF TEMPERATURE1 (HT1; Hashimoto et al., 2006) and its downstream targets CONVERGENCE OF BLUE LIGHT AND CO2 1 (CBC1) and CBC2 (Hiyama et al., 2017). Low CO2 signaling most likely inhibits S-type anion channels (Xue et al., 2011; Hõrak et al., 2016; Hiyama et al., 2017), which are critical channels not only for anion efflux during stomatal closure (Vahisalu et al., 2008; Geiger et al., 2011) but also for the indirect homeostatic regulation of cytosolic pH and Ca2+, which in turn affects K+ uptake and thus stomatal opening (Wang et al., 2012). The ht1 and cbc1 cbc2 mutants do not exhibit clear increases in stomatal conductance in response to red light as well as low CO2 levels (Matrosova et al., 2015; Hiyama et al., 2017). Moreover, it is noteworthy that a high concentration of CO2 inhibits PM H+-ATPase (Edwards and Bowling, 1985), giving rise to the hypothesis that the reduction of Ci may release PM H+-ATPase from the inactivating effects of high Ci.

Evidence has been presented that red light induces stomatal opening even under constant Ci (Messinger et al., 2006; Lawson et al., 2008), which suggests that a Ci-independent mechanism also is involved in red light-induced stomatal opening. Guard cells in most plant species contain chloroplasts (Lawson, 2009), with the exception of orchids of the genus Paphiopedilum (Zeiger, 1983), and photosynthesis in guard cell chloroplasts provides the ATP required for H+ pumping by activated PM H+-ATPase (Tominaga et al., 2001). Mesophyll photosynthesis also may promote the accumulation of ATP in guard cells during light-induced stomatal opening (Wang et al., 2014a). In addition, recent studies have suggested that sugars accumulate not only as osmolytes but also as metabolic substrates for the production of ATP and/or malate2–, a counterion of K+, via glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle in guard cells (Daloso et al., 2016). Furthermore, the red/far-red light photoreceptor phytochrome B (phyB) regulates a transcript of MYB60, a transcription factor that affects stomatal apertures (Cominelli et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2010).

Previously, we established an immunohistochemical technique to visualize the phosphorylation level of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells using isolated epidermis (Hayashi et al., 2011). Conventional analyses using GCPs require large-scale cultivation of plants and usually take a long time to prepare the protoplasts. By contrast, the immunohistochemical technique using isolated epidermis enables us to analyze the PM H+-ATPase more easily. However, despite the great usefulness of the previously developed immunohistochemical technique, it still requires isolation of the epidermis, so its range of application is restricted by the availability of plant epidermis. To overcome this issue, we established an immunohistochemical technique using whole leaves instead of isolated epidermis and, unexpectedly, found that red light induces phosphorylation of the penultimate C-terminal residue, Thr, of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells in whole leaves. We further characterized this red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase and investigated its correlation with stomatal opening in whole leaves. Our findings indicate that red light induces the photosynthesis-dependent phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells to promote stomatal opening in whole leaves.

RESULTS

An Immunohistochemical Technique Using Whole Leaves and Detection of Red Light-Induced Phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells

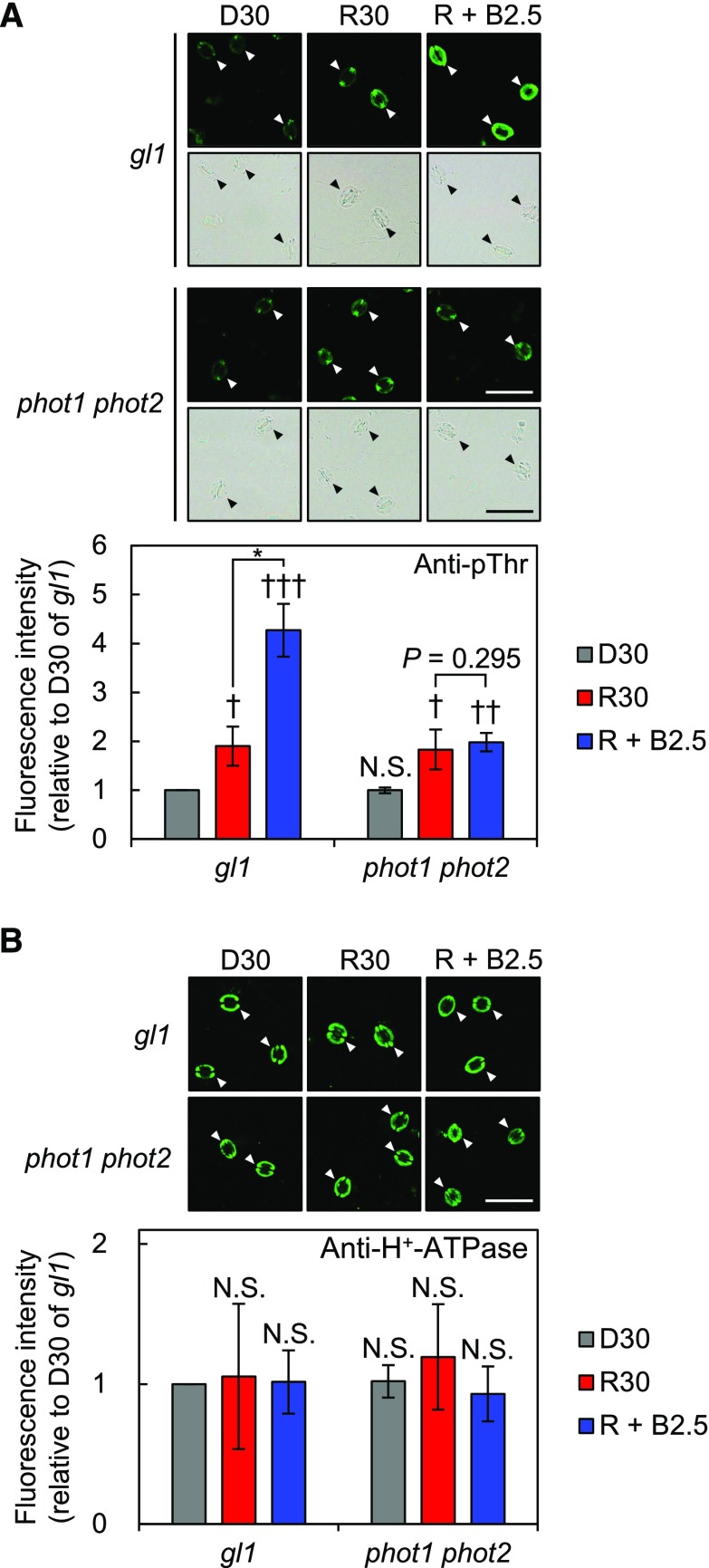

Previous success with immunohistochemical analyses using isolated epidermis enabled us to analyze the phosphorylation status of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells more easily than with conventional analyses using GCPs (Hayashi et al., 2011). However, that technique still requires isolation of the epidermis, so it is impractical for studying plants from which sufficient epidermis cannot be isolated. To overcome this weakness, we conducted immunohistochemical analyses using whole leaves. To this end, a syringe was used to infiltrate the fixative quickly into the leaves and then excessive leaf tissue, except the epidermis, was removed enzymatically on microscope slides during tissue permeabilization (see “Materials and Methods”). To test whether this method would allow us to detect PM H+-ATPase protein and phosphorylation of the penultimate residue, Thr, in guard cells, we investigated phototropin (phot1 and phot2)-mediated blue light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase using anti-pThr and anti-H+-ATPase antisera. As expected, the phosphorylation level of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells was statistically significantly higher with weak blue light (5 μmol m–2 s–1) superimposed on background red light (600 μmol m–2 s–1) than with red light alone in glabra1 (gl1; Fig. 1A), the control plant of phot1 phot2 (Kinoshita et al., 2001). By contrast, blue light-induced phosphorylation was abolished completely in phot1 phot2 (Fig. 1A). The amount of PM H+-ATPase did not differ depending on the light conditions or genotype, as described previously (Fig. 1B; Hayashi et al., 2011). These results verified that our new method works.

Figure 1.

Establishment of an immunohistochemical technique using whole leaves to detect PM H+-ATPase in guard cells. Phosphorylation (A) and amount of PM H+-ATPase (B) in guard cells in whole leaves from gl1 and phot1 phot2 are shown. Phosphorylation or amount of the protein was detected using anti-pThr or anti-H+-ATPase antiserum, respectively. Mature leaves harvested from dark-adapted plants were illuminated with red light (600 µmol m–2 s–1) for 30 min (R30) followed by blue light (5 µmol m–2 s–1) superimposed on red light for 2.5 min (R + B2.5) or kept in the dark (D30). Typical fluorescence and corresponding bright-field images (top) and quantification of the fluorescence intensities (bottom) are shown. Arrowheads indicate guard cells. Data represent means of relative values from three independent measurements with sd. A, Daggers denote that the mean is statistically significantly higher than D30 of gl1 set to 1. N.S., Not significant (one-tailed one-sample Student’s t test: †, P < 0.05; ††, P < 0.01; †††, P < 0.005; and N.S., P = 0.516). The asterisk indicates that the mean of R + B2.5 is statistically significantly higher than that of R30 in gl1 (one-tailed Student’s test: *, P < 0.005). B, The means were not statistically significantly different from D30 of gl1 set to 1 (two-tailed one-sample Student’s t test: N.S., P > 0.45). Bars = 50 µm.

Interestingly, we found that the phosphorylation level of whole gl1 leaves illuminated with red light alone was statistically significantly higher, by about 90%, than that of gl1 leaves kept in the dark (Fig. 1A). Consistent with this, red light also increased the phosphorylation level by about 82% in phot1 phot2 (Fig. 1A). Red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells was confirmed in whole leaves from wild-type Columbia-0 (Col-0) and isolated epidermis immediately prepared from illuminated Col-0 leaves (Supplemental Fig. S1), which suggests that it is not caused by mutations in GL1 or some artifact inherent to the technique. In addition, we confirmed that the same fluence rate of red light used to illuminate whole leaves did not induce phosphorylation in isolated epidermis (Supplemental Fig. S2A). These results clearly indicate that the phosphorylation status of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells is regulated by red light in whole leaves of Arabidopsis.

Red Light-Induced Phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells Correlates with Stomatal Opening in Whole Leaves

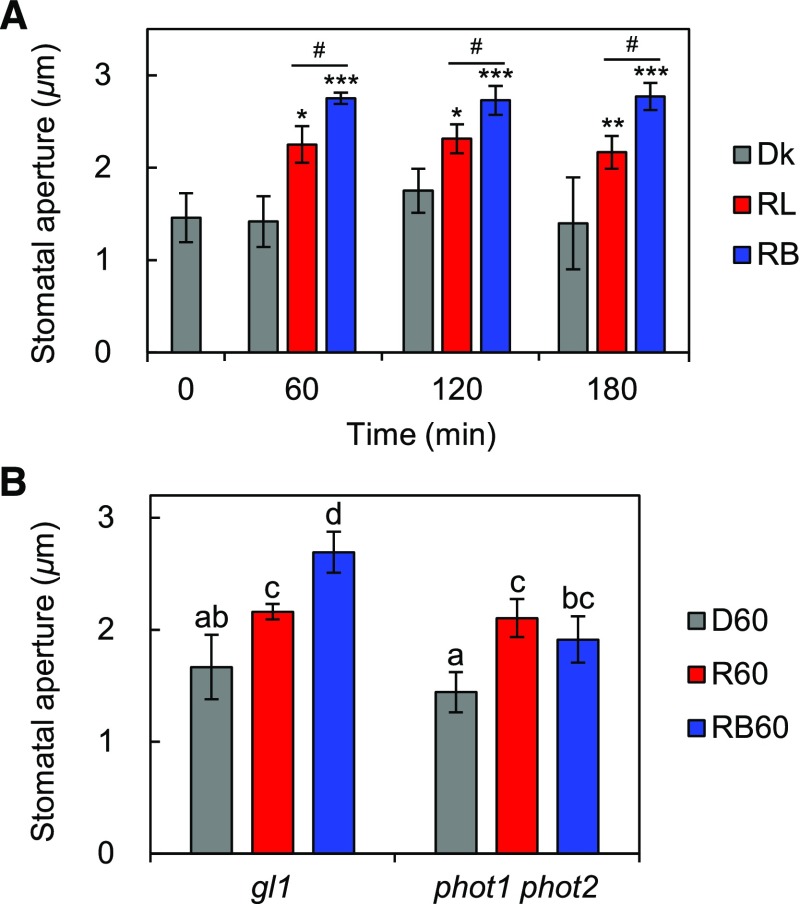

The activation of PM H+-ATPase via phosphorylation of the penultimate residue, Thr, of PM H+-ATPase is important in blue light-induced stomatal opening (Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999, 2002). Thus, we investigated the relationship between this phosphorylation and red light-induced stomatal opening in whole leaves. In accordance with the phosphorylation status of PM H+-ATPase shown in Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure S1A, red light statistically significantly induced stomatal opening in whole leaves (Fig. 2). The size of the stomatal aperture in red light-illuminated leaves was intermediate between that of leaves illuminated with both red and blue light and dark-kept leaves in both Col-0 (Fig. 2A) and gl1 (Fig. 2B). Red light-induced stomatal opening in whole leaves was saturated for at least 60 min (Fig. 2A) and detectable even in phot1 phot2 (Fig. 2B). These results are consistent with previous gas-exchange experiments showing a red light-dependent increase in stomatal conductance (Doi et al., 2004; Shimazaki et al., 2007; Suetsugu et al., 2014; Yamauchi et al., 2016). In isolated epidermis, red light did not induce stomatal opening within the measurement period used here (up to 180 min), and only blue light superimposed on red light induced stomatal opening (Supplemental Fig. S2B).

Figure 2.

Light-induced stomatal opening in whole leaves. A, Mature leaves harvested from dark-adapted Col-0 plants (0 min) were illuminated with red light (RL), both red and blue light (RB), or kept in the dark (Dk) for 60, 120, or 180 min. Light intensities were 600 µmol m–2 s–1 for red light and 5 µmol m–2 s–1 for blue light. Data represent means of representative values from three independent measurements with sd. Asterisks denote statistically significant increases in the mean compared with that of 0 min (one-tailed Dunnett’s test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001). Hash signs indicate that the mean of RB is statistically significantly higher than that of RL at each time point (one-tailed Student’s t test: #, P < 0.05). B, Light-induced stomatal opening in whole leaves from gl1 and phot1 phot2. Mature leaves harvested from dark-adapted plants were illuminated with red light (R60), both red and blue light (RB60), or kept in the dark (D60) for 60 min. Light intensities were the same as in A. Data represent means of representative values from four independent measurements with sd. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among means (Tukey’s test: P < 0.05).

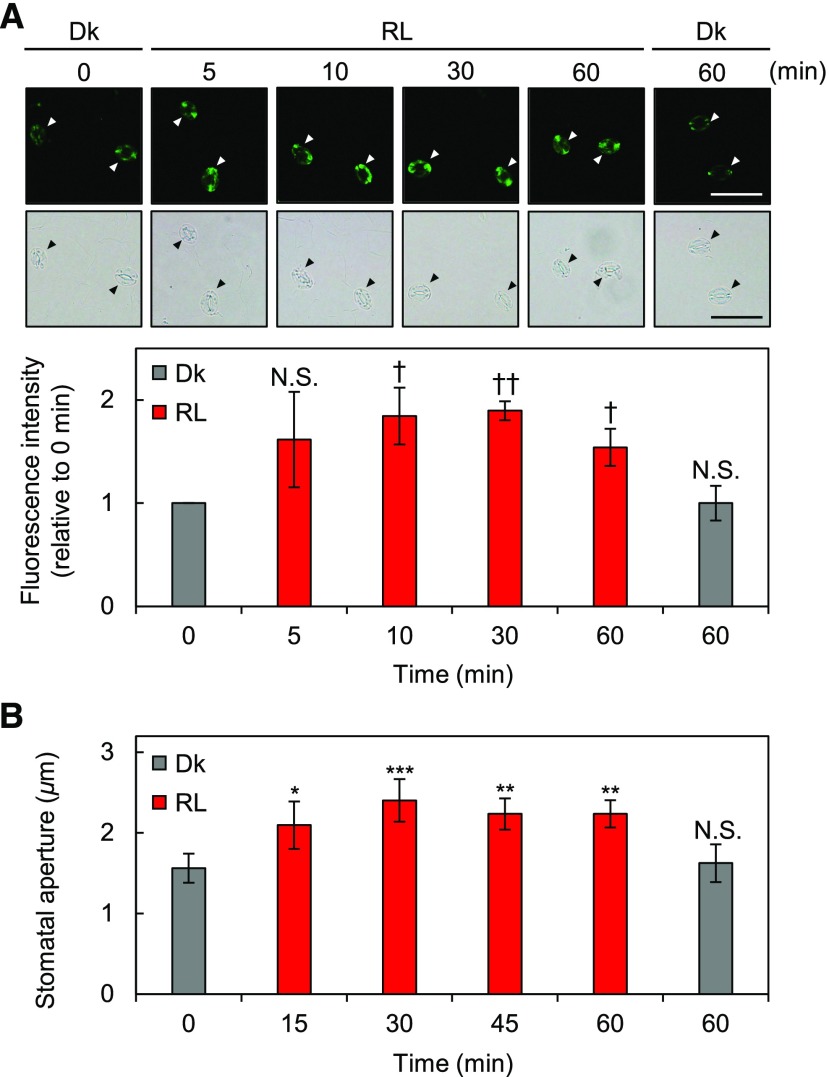

Next, we performed a time-course experiment within a period of 60 min to characterize the initial red light responses using whole leaves. As shown in Figure 3A, the phosphorylation level of PM H+-ATPase was up-regulated within 10 min of the start of illumination and saturated around 30 min. Red light induced stomatal opening within at least 15 min after the start of illumination, and the size of the aperture reached a stable level within 60 min (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells correlates with red light-induced stomatal opening.

Figure 3.

Initial responses to red light in guard cells in whole leaves. Mature leaves were harvested from dark-adapted plants (0 min) and kept in the dark (Dk) for 60 min or illuminated with red light (RL; 600 µmol m–2 s–1) for the indicated times. A, Immunohistochemical detection of the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells using anti-pThr antiserum. Leaves were illuminated for 5, 10, 30, or 60 min. Typical fluorescence and bright-field images (top) and quantification of the fluorescence intensities (bottom) are shown. Arrowheads indicate guard cells. Data represent means of relative values from three independent measurements with sd. Daggers denote that the mean is statistically significantly higher than at 0 min set to 1. N.S., Not significant (one-tailed one-sample Student’s t test: †, P < 0.05; ††, P < 0.005; and N.S., P > 0.07). Bar = 50 µm. B, Measurement of red light-induced stomatal opening. Leaves were illuminated for 15, 30, 45, or 60 min. Data represent means of representative values from three independent measurements with sd. Asterisks denote statistically significant increases of the mean compared with that of 0 min (one-tailed Dunnett’s test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005; and N.S., P = 0.717).

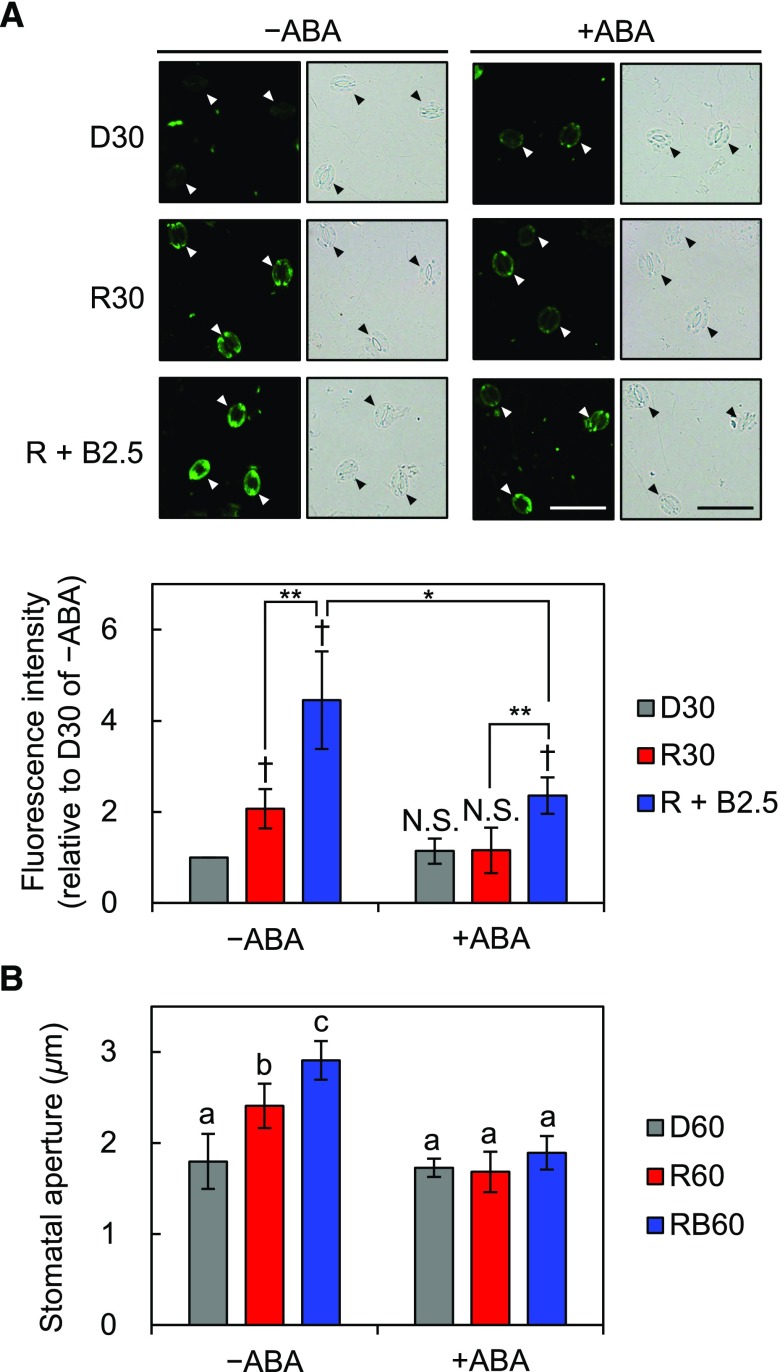

Exogenous Abscisic Acid Suppresses Red Light-Induced Phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells and Stomatal Opening

Abscisic acid (ABA) inhibits blue light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells and stomatal opening (Zhang et al., 2004; Hayashi et al., 2011). Thus, we investigated the effects of ABA on red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells and stomatal opening in whole leaves. As shown in Figure 4A, 20 µm ABA completely suppressed red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase and partially suppressed blue light-induced phosphorylation. The net blue light-induced phosphorylation decreased by approximately 41% compared with that of untreated leaves (Supplemental Fig. S3). Moreover, stomata in ABA-treated leaves did not open after exposure to red or blue light (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that exogenous ABA decreases the apparent phosphorylation level of PM H+-ATPase under any light quality in whole leaves.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of the light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells and stomatal opening in whole leaves by the phytohormone ABA. Mature leaves harvested from dark-adapted plants were pretreated with 20 µm ABA dissolved in 0.1% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; +ABA) or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO alone (–ABA) for 30 min in the dark before light illumination. A, Immunohistochemical detection of the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells using anti-pThr antiserum. Pretreated leaves were illuminated with red light (600 µmol m–2 s–1) for 30 min (R30) followed by blue light (5 µmol m–2 s–1) superimposed on red light for 2.5 min (R + B2.5) or kept in the dark (D30). Typical fluorescence and bright-field images (top) and quantification of the fluorescence intensities (bottom) are shown. Data represent means of relative values from four independent measurements with sd. Daggers denote that the mean is statistically significantly higher than D30 of –ABA set to 1. N.S., Not significant (one-tailed one-sample Student’s t test: †, P < 0.01; and N.S., P > 0.18). Asterisks indicate that the mean of R + B2.5 is statistically significantly higher than that of R30 within each treatment and that the mean of R + B2.5 of +ABA is statistically significantly lower than that of –ABA (one-tailed Student’s t test: *, P < 0.01; and **, P < 0.005). Bars = 50 µm. B, Measurement of light-induced stomatal opening under ABA treatment. Pretreated leaves were illuminated with red light (R60), both red and blue light (RB60), or kept in the dark (D60) for 60 min. Light intensities were the same as in A. Data represent means of representative values from four independent measurements with sd. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among means (Tukey’s test: P < 0.05).

AHA1, a Major Isoform of PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells, Is Responsible for Red Light-Induced Stomatal Opening

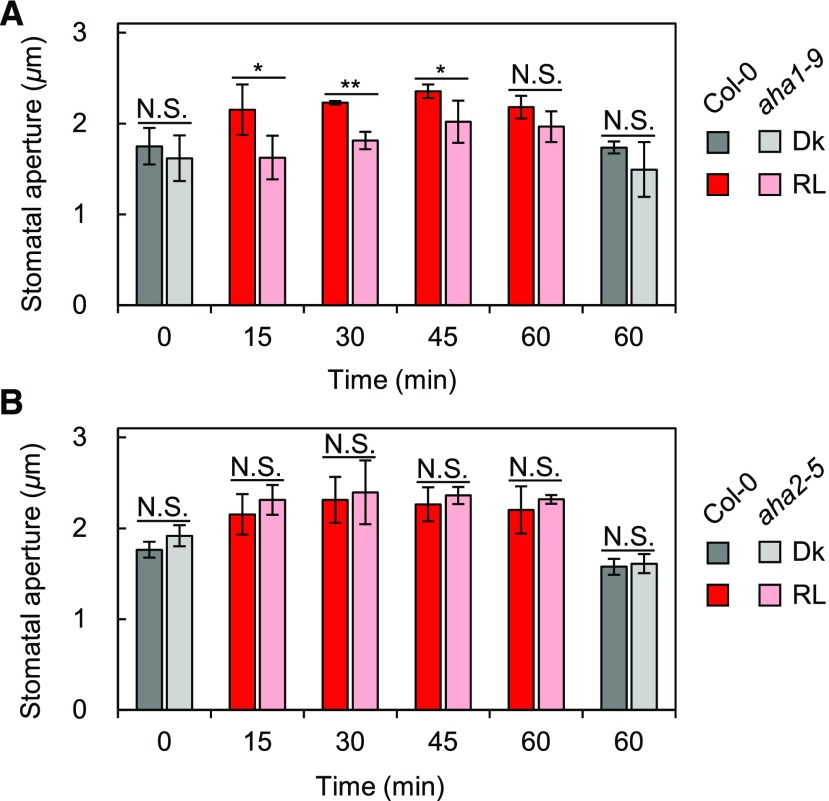

A recent study suggested that AHA1 constitutes the majority of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells, probably due to some posttranscriptional regulation, as the transcript level of AHA1 in guard cells is not the highest among those of the isogenes; AHA1 is responsible for blue light-induced stomatal opening, and the red light-dependent increase in stomatal conductance is statistically significantly slower in aha1 plants than in the wild type (Yamauchi et al., 2016). To confirm the need for PM H+-ATPase for red light-induced stomatal opening genetically, we analyzed stomatal apertures in whole leaves from PM H+-ATPase mutant plants. As shown in Figure 5A, stomata in aha1-9, a null allele of AHA1 leading to 65% reduction in the amount of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells (Yamauchi et al., 2016), were found to have smaller apertures than those in the wild type until 45 min after the start of red light illumination. The aperture reached a level comparable to that in the wild type within 60 min, in agreement with previous gas-exchange measurements (Yamauchi et al., 2016). By contrast, the stomatal opening in aha2-5, a knockout allele of AHA2 (Hayashi et al., 2011), was indistinguishable from that of the wild type (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that AHA1 is responsible for stomatal opening in response to red light as well as blue light. The delayed red light-induced stomatal opening in aha1-9 indicates that PM H+-ATPase is necessary to accelerate red light-induced stomatal opening in whole leaves.

Figure 5.

Red light-induced stomatal opening in whole leaves from PM H+-ATPase mutants. Mature leaves from aha1-9 (A) or aha2-5 (B) and Col-0 were harvested from dark-adapted plants. The harvested leaves were kept in the dark (Dk) for 60 min or illuminated with red light (RL; 600 µmol m–2 s–1) for 15, 30, 45, or 60 min. Data represent means of representative values from three independent measurements with sd. A, Asterisks denote statistically significant decrements of the mean of aha1-9 compared with that of Col-0 at each time point. N.S., Not significant (one-tailed Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001; and N.S., P > 0.07). B, The mean of aha2-5 was not statistically significantly lower than that of Col-0 at each time point (one-tailed Student’s t test: N.S., P > 0.6).

Red Light-Induced Phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells Depends on Photosynthesis

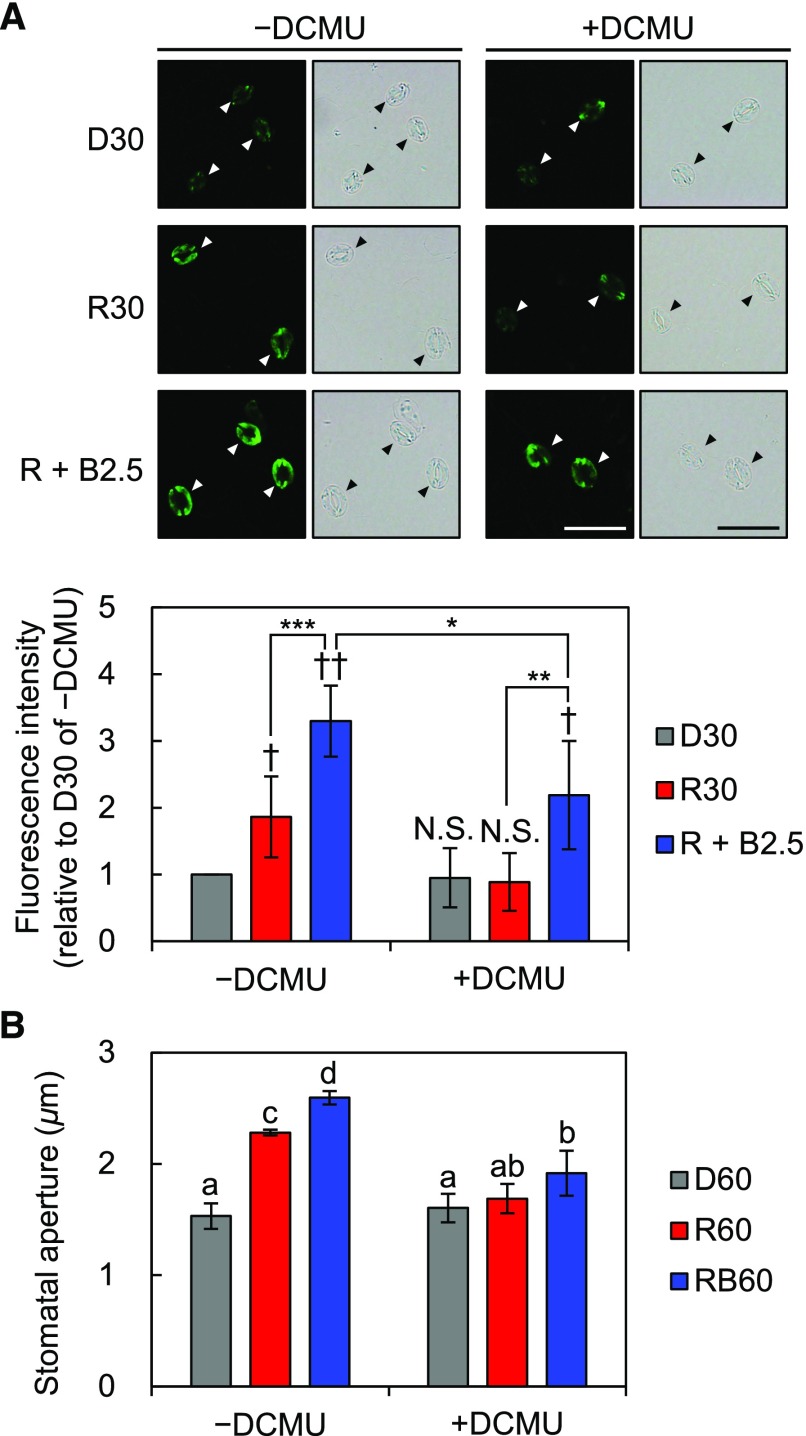

Red light-induced stomatal opening depends on photosynthesis (Sharkey and Raschke, 1981; Doi and Shimazaki, 2008; Wang et al., 2011; Suetsugu et al., 2014). Thus, we investigated the effects of DCMU, an inhibitor of photosynthetic electron transport, on the stomatal responses to red light in whole leaves. As shown in Figure 6A, red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase was completely inhibited by 10 µm DCMU. Accordingly, stomata in DCMU-treated leaves showed no significant increase in the size of apertures in response to red light (Fig. 6B). The inhibition of red light-induced stomatal opening is in agreement with the previous gas-exchange experiment showing that DCMU diminished the red light-dependent increase in stomatal conductance (Suetsugu et al., 2014). Additional blue light induced phosphorylation even with DCMU, as described previously (Suetsugu et al., 2014); however, the phosphorylation level appeared to be lower than that of untreated leaves (Fig. 6A; Supplemental Fig. S3). Blue light-induced stomatal opening also was suppressed by DCMU (Fig. 6B). Next, we investigated red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells in phyA phyB, a mutant of phytochromes. The results showed that red light induced phosphorylation in phyA phyB without affecting the amount of PM H+-ATPase (Supplemental Fig. S4). These results indicate that red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase is regulated by photosynthesis but not by phytochrome-mediated red light signaling.

Figure 6.

Effects of the photosynthesis inhibitor DCMU on the light responses of guard cells in whole leaves. Mature leaves harvested from dark-adapted plants were pretreated with 10 µm DCMU dissolved in 0.1% (v/v) DMSO (+DCMU) or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO alone (–DCMU) for 30 min in the dark before light illumination. A, Immunohistochemical detection of the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells using anti-pThr antiserum. Pretreated leaves were illuminated with red light (600 µmol m–2 s–1) for 30 min (R30) followed by blue light (5 µmol m–2 s–1) superimposed on red light for 2.5 min (R + B2.5) or kept in the dark (D30). Typical fluorescence and bright-field images (top) and quantification of the fluorescence intensities (bottom) are shown. Arrowheads indicate guard cells. Data represent means of relative values from five independent measurements with sd. Daggers indicate that the mean is statistically significantly higher than D30 of –DCMU set to 1. N.S., Not significant (one-tailed one-sample Student’s t test: †, P < 0.05; ††, P < 0.001; and N.S., P > 0.58). Asterisks indicate that the mean of R + B2.5 is statistically significantly higher than that of R30 within each treatment and that the mean of R + B2.5 of +DCMU is statistically significantly lower than that of –DCMU (one-tailed Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.005). Bars = 50 µm. B, Measurement of light-induced stomatal opening under DCMU treatment. Pretreated leaves were illuminated with red light (R60), both red and blue light (RB60), or kept in the dark (D60) for 60 min. Light intensities were the same as in A. Data represent means of representative values from four independent measurements with sd. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among means (Tukey’s test: P < 0.05).

Effects of Suc or CO2 on Phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells

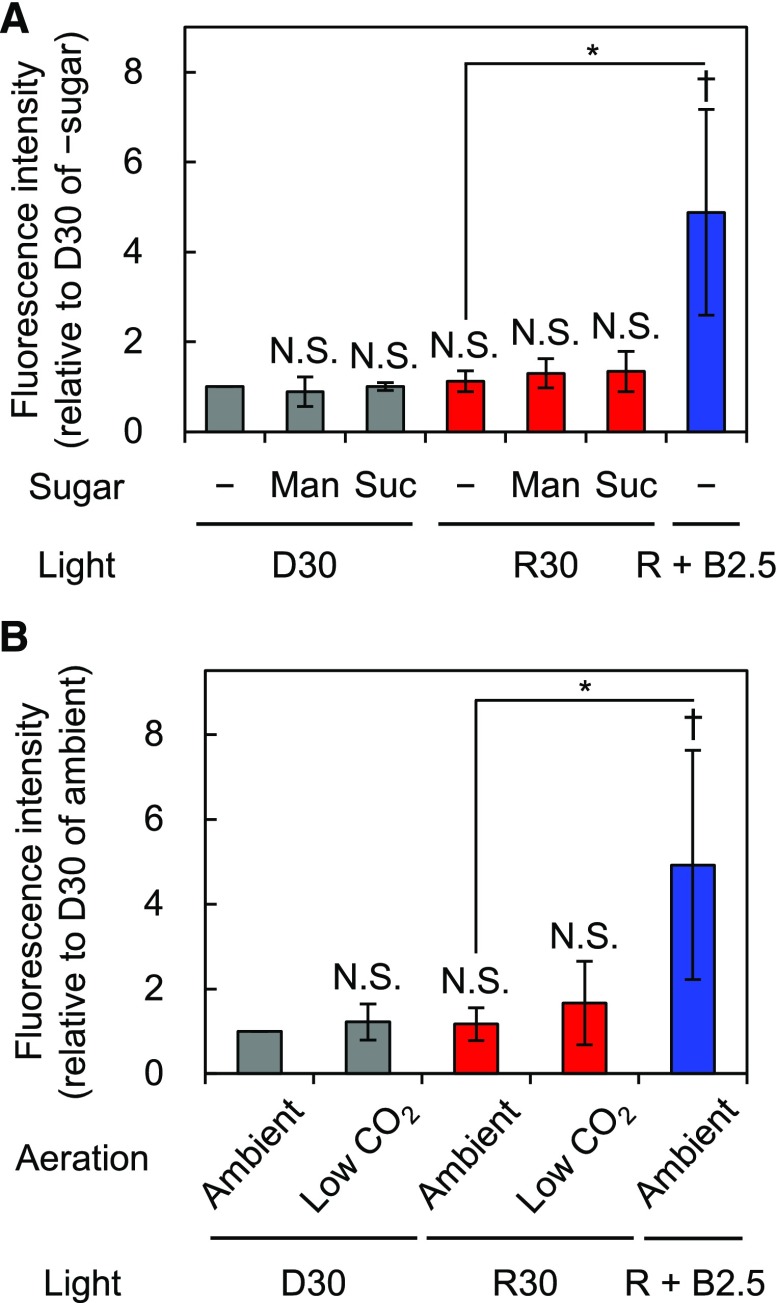

To clarify the signaling components mediating photosynthesis and red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells, we first assumed that photosynthetic products might be the responsible signal. Suc is the primary photosynthetic product and accumulates in guard cells partly by photosynthesis in guard cell chloroplasts and partly by import from mesophyll cells via apoplasts (Poffenroth et al., 1992; Talbott and Zeiger, 1993; Lu et al., 1997). In whole leaves, Suc content increases beginning approximately 5 min after the start of illumination (Okumura et al., 2016); in line with this, we found that red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells required more than 5 min of illumination (Fig. 3A). Thus, we investigated the effects of Suc, or the same concentration of mannitol as an osmotic control, on the phosphorylation status of PM H+-ATPase in the guard cells of isolated epidermis samples in the dark or under red light. As shown in Figure 7A, the application of Suc to isolated epidermis did not induce the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells in the dark. In addition, simultaneous application of Suc and red light did not induce the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in isolated epidermis.

Figure 7.

Effects of Suc or CO2 concentration on the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells in isolated epidermis. Immunohistochemical detection of the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in stomatal guard cells using anti-pThr antiserum is shown. Epidermal tissue was illuminated with red light (600 µmol m–2 s–1) for 30 min (R30) followed by blue light (5 µmol m–2 s–1) superimposed on red light for 2.5 min (R + B2.5) or kept in the dark (D30) with the indicated conditions. A, Epidermis was incubated without (–) or with 30 mm mannitol (Man) or Suc. B, Experimental basal buffer was aerated with ambient or soda lime-passed low-CO2 air (CO2 = 30–40 µL L−1). The quantification of fluorescence intensities is shown. Data represent means of relative values from independent measurements (A, n = 4; B, n = 5) with sd. Daggers denote that the mean is statistically significantly higher than D30 of –sugar (A) or that of ambient (B) set to 1. N.S., Not significant (one-tailed one-sample Student’s t test: †, P < 0.05; N.S. [A], P > 0.08; and N.S. [B], P > 0.10). Asterisks indicate that the mean of R + B2.5 is statistically significantly higher than that of R30 with a corresponding control condition (one-tailed Student’s t test: *, P < 0.01).

Red light causes the reduction of Ci via photosynthesis. A high concentration of CO2 may inhibit PM H+-ATPase (Edwards and Bowling, 1985), raising the hypothesis that high Ci inactivates PM H+-ATPase. Therefore, we investigated the effects of reduced Ci on the phosphorylation status of PM H+-ATPase. In this experiment, isolated epidermis samples were incubated with aeration by diffused ambient or soda lime-passed low-CO2 air for 30 min in the dark or under red light (Supplemental Fig. S5; see “Materials and Methods”). As shown in Figure 7B, low-CO2 conditions neither induced the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in the dark nor provoked red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in isolated epidermis.

DISCUSSION

New Immunohistochemical Technique for Guard Cells Using Whole Leaves

Immunohistochemical staining using isolated epidermis enables one to determine the amount of PM H+-ATPase using anti-H+-ATPase antibodies and the phosphorylation status of PM H+-ATPase using anti-pThr antibodies in stomatal guard cells (Hayashi et al., 2011). However, when using the method, it is necessary to prepare enough isolated epidermis for experiments. Therefore, it is not practical for studying plants with small and/or few leaves, such as dwarf or early-flowering mutants. In addition, the method cannot be used for the analysis of individual plants, such as genetic screening, in which only single and often small leaves are used. Overcoming these issues, the newly developed immunohistochemical technique using whole leaves enables various applications, regardless of the availability of isolated epidermis.

Using this method, we found that red light induces the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells of whole leaves (Figs. 1A and 3A). According to our results, in isolated epidermis, red light did not induce the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells or stomatal opening (Supplemental Fig. S2; Hayashi et al., 2011; Suetsugu et al., 2014). Hence, an additional advantage of our modified technique is that stomatal responses in whole leaves can be analyzed.

Red Light Induces Photosynthesis-Dependent Phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells and Stomatal Opening in Whole Leaves

Activation of PM H+-ATPase induces PM hyperpolarization and drives K+ uptake through voltage-gated inward-rectifying K+ channels (Inoue and Kinoshita, 2017; Jezek and Blatt, 2017). Blue light activates PM H+-ATPase via phosphorylation of the penultimate C-terminal residue of PM H+-ATPase, Thr (Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999, 2002). Red light also leads to the accumulation of K+ in guard cells, which may require PM H+-ATPase activity (Hsiao et al., 1973; Olsen et al., 2002). However, whether and how red light activates PM H+-ATPase has remained unclear. We found that red light induces DCMU-sensitive phosphorylation of the Thr of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells, which correlates with red light-induced stomatal opening in whole leaves (Figs. 1–3 and 6). PM H+-ATPase was genetically confirmed to be necessary to accelerate red light-induced stomatal opening (Fig. 5). The eventual stomatal opening in aha1-9 (Fig. 5A) suggests that other PM H+-ATPase isoforms make minor contributions to red light-induced stomatal opening. This idea is supported by the previous observation that the activation of PM H+-ATPase by fusicoccin ultimately induces full stomatal opening in aha1 (Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 2001; Yamauchi et al., 2016). These results strongly suggest that red light induces stomatal opening through the activation of PM H+-ATPase by photosynthesis-dependent phosphorylation in whole leaves and provide insight into the photosynthetic regulation of stomatal opening.

The absence of red light responses in isolated epidermis (Supplemental Fig. S2) suggests that mesophyll photosynthesis is most likely to be required for red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase and, thus, stomatal opening. Indeed, enhancement of red light-induced stomatal opening by mesophyll cells also was reported in other species. In Vicia faba, red light induced stomatal opening even in isolated epidermis (Schwartz and Zeiger, 1984); however, the amplitude of the response was estimated to be much smaller than that in leaf discs (Hsiao et al., 1973; for review, see Mott, 2009). In Chlorophytum comosum, the red light-dependent increase in stomatal conductance was abolished in albino leaf patches, in which guard cell chloroplasts were indicated to be functional (Roelfsema et al., 2006). Such enhancement could be explained, at least in part, by the hypothesis that mesophyll photosynthesis primarily induces the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells. However, measurable red light-induced stomatal opening in isolated epidermis in V. faba (Schwartz and Zeiger, 1984) suggests that guard cell chloroplasts in this species partially contribute to red light-induced stomatal opening. Even with the same incubation solution wherein red light induced stomatal opening in V. faba isolated epidermis (Schwartz and Zeiger, 1984), red light is not likely to induce the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in Arabidopsis isolated epidermis (Supplemental Fig. S6). Nevertheless, guard cell chloroplasts in certain species might have the potential to induce the partial phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase, which could cause the interspecific difference in the red light sensitivity of guard cells in isolated epidermis. Analyses of red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in whole leaves from mutant or transgenic plants with a defect in photosynthetic activity, either in mesophyll cells or in guard cells, would provide further insight into whether mesophyll cells or guard cell chloroplasts contribute to this response. In addition, application of our immunohistochemical technique to other species could be considered for future study.

Effects of ABA on Red Light-Induced Stomatal Opening in Whole Leaves

This study indicates that ABA suppresses red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells and stomatal opening (Fig. 4). ABA was suggested to have no direct effect on photosynthesis (Kriedemann et al., 1975; Mawson et al., 1981; Lauer and Boyer, 1992). Therefore, the inhibition of red light-induced stomatal opening by ABA may be achieved by suppressing the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase rather than by a direct limitation of photosynthesis and also may be enhanced by ABA-induced stomatal closure via anion and cation efflux from guard cells (Jezek and Blatt, 2017). In addition, the inactivation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells also may reduce photosynthesis-dependent Suc accumulation as osmolytes through H+/Suc symporters in these cells, as predicted previously in silico (Sun et al., 2014). A previous study indicated that ABA suppresses blue light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase via early ABA signaling components including ABI1, ABI2, and OST1 (Hayashi et al., 2011). Further genetic elucidation is required to reveal whether these ABA signaling components are involved in the suppression of red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase.

What Mediates the Photosynthesis-Dependent Phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells?

Neither Suc as a major photosynthetic product nor low-CO2 conditions, which mimic the reduced Ci caused by photosynthesis, induced the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase even with red light illumination (Fig. 7). These results suggest that the simultaneous application of Suc and red light, or low-CO2 conditions and red light, is not sufficient for the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells. Taken together with a previous report suggesting that high Ci inhibits PM H+-ATPase (Edwards and Bowling, 1985), reduced Ci may be necessary but not sufficient for the activation of PM H+-ATPase. Thus, a Ci-independent mechanism also may be involved in the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase, consistent with the Ci independence of red light-induced stomatal opening (Messinger et al., 2006; Lawson et al., 2008). In summary, identification of the signal(s) mediating the photosynthesis-dependent phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells will be a critical issue for future work, and the combination of low CO2 and other putative signal(s) should be a focus of further studies.

Ci also is suggested to affect the transport of anions and cations across the PM of guard cells (Brearley et al., 1997; Roelfsema et al., 2002). Reduced Ci is likely to inhibit S-type anion channels via low-CO2 signaling mediated by HT1, CBC1, and CBC2 (Hiyama et al., 2017). Guard cells from cbc1 cbc2 showed reduced voltage-dependent inward-rectifying K+ current, although the reduction of the K+ current did not limit the rate of stomatal opening induced by fusicoccin (Hiyama et al., 2017). Red light-induced stomatal opening is delayed in aha1 (Fig. 5A; Yamauchi et al., 2016) and suppressed in ht1 and cbc1 cbc2 (Matrosova et al., 2015; Hiyama et al., 2017; Supplemental Fig. S7). A possible explanation for these distinct phenotypes is that proper regulation of anion and cation transporters at the PM of guard cells is a prerequisite for the acceleration of red light-induced stomatal opening by activated PM H+-ATPase. Alternatively, the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase might be affected in ht1 and cbc1 cbc2 regardless of Ci. Further analyses are required to test these hypotheses.

Light-Induced Stomatal Opening in Whole Leaves Mediated by PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells

Based on our results here, we propose a possible model for light-induced stomatal opening in whole leaves mediated by PM H+-ATPase. As shown in Supplemental Figure S8, blue light and red light induce the phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase via phototropin-mediated signaling and photosynthesis, respectively. In addition, red light seems to enhance blue light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in a photosynthesis-independent manner (Suetsugu et al., 2014). Thus, photosynthesis at least provides the ATP required for H+ pumping by activated PM H+-ATPase to promote stomatal opening (Tominaga et al., 2001; Suetsugu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014a). Our results suggest that blue light signaling and photosynthetic status are integrated into the activation of PM H+-ATPase. Considering that stomatal apertures are a limiting factor in photosynthesis (Wang et al., 2014b), this mechanism may enable plants to promote stomatal opening and CO2 uptake in response not only to the light environment but also to the actual CO2 demand caused by photosynthesis in whole leaves. Further investigation of the phosphorylation level of PM H+-ATPase in whole leaves under various light conditions should provide a better understanding of light-induced stomatal opening mediated by PM H+-ATPase in whole leaves.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Col-0 plants were used as the wild type in the physiological experiments, unless stated otherwise. Col-0 also was used as a control plant for aha1-9 (SAIL_1285_D12; Yamauchi et al., 2016), aha2-5 (SALK_022010; Haruta et al., 2010), ht1-9 (Hiyama et al., 2017), and cbc1 cbc2 (SALK_005187 for cbc1 and SAIL_740_G01 for cbc2; Hiyama et al., 2017). gl1 and Landsberg erecta were used as control plants for phot1-5 phot2-1 (phot1 phot2; Kinoshita et al., 2001) and phyA-201 phyB-1 (phyA phyB; Mazzella et al., 1997), respectively. All plants were grown on soil under white fluorescent lamps (approximately 50 µmol m–2 s–1) with a 16/8-h light/dark cycle in a growth room. Growth temperature and relative humidity were approximately 20°C to 24°C and 40% to 60%, respectively. Three- to 5-week-old plants were used for the experiments.

Light Source

Red and blue light were produced from light-emitting photodiodes (ISL-150X150-H4RR for red light only and ISL-150X150-H4RHB for both red and blue light; CCS) with a manufacturer-provided power supply (ISC-201-2; CCS). Photon flux densities were confirmed using a quantum meter (Li-250; Li-Cor).

Light Illumination, Chemical Treatment, and Aeration

Epidermal fragments were obtained by blending leaves for less than 10 s (less than 5 s twice) in Milli-Q water (Millipore) with a Waring blender equipped with an MC1 mini container (Waring Commercial) at full speed and collected in a 58-µm nylon mesh. Isolated epidermis or whole leaves harvested from dark-adapted plants were incubated in or put on the basal buffer (5 mm MES-1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino] propane [pH 6.5], 50 mm KCl, and 0.1 mm CaCl2) and illuminated with red light (600 µmol m–2 s–1) or kept in the dark. Blue light (5 µmol m–2 s–1) was superimposed on the background red light. For pretreatment of leaves with ABA or DCMU, these compounds were dissolved in DMSO. The harvested leaves were kept in the dark for 30 min on the basal buffer containing 20 µm ABA or 10 µm DCMU, or DMSO alone, and then transferred to the indicated light conditions. The final concentration of DMSO was 0.1% (v/v). To examine the effects of Suc, isolated epidermis was kept in the basal buffer containing 30 mm Suc or the same concentration of mannitol as an osmotic control for 30 min in the dark or under red light. The epidermis also was illuminated or kept in the dark as described above without sugars. To examine the effects of low-CO2 conditions, isolated epidermis was incubated in a glass dish (i.d. approximately 21 mm × 10 mm height) containing 1.5 mL of basal buffer aerated with ambient or soda lime-passed air (CO2, 30–40 µL L−1) at a flow rate of approximately 50 cm3 min–1 and illuminated or kept in the dark as described above. The basal buffer was aerated from at least 30 min before and throughout the incubation. A schematic diagram of the experimental setup is shown in Supplemental Figure S5.

Antisera

Previously described antisera against the catalytic domain of PM H+-ATPase or its penultimate phosphorylated residue, Thr, designated as anti-H+-ATPase or anti-pThr, respectively (Hayashi et al., 2010), were used to estimate the amount of the protein and its phosphorylation level, respectively.

Immunohistochemical Detection of PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells Using Whole Leaves

We modified a previously described whole-mount immunohistochemical technique (Sauer et al., 2006) as described below to detect PM H+-ATPase in guard cells in whole leaves. The pH of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mm NaCl, 8.1 mm Na2HPO4, 2.68 mm KCl, and 1.47 mm KH2PO4) was adjusted to 6.5 by HCl for sample rehydration and enzyme treatment, whereas unadjusted PBS was used in all other experimental steps. To fix leaves, fixative composed of 4% (w/v) formaldehyde with 0.3% (w/w) glutaraldehyde in microtubule-stabilizing buffer (MTSB; 50 mm PIPES-NaOH [pH 7], 5 mm MgSO4, and 5 mm EGTA) was freshly prepared from paraformaldehyde (Wako) and 25% (w/w) glutaraldehyde stock solution (Nacalai Tesque). After light treatment, the fixative was infiltrated immediately into the leaves as follows. Leaves and the fixative were put into a syringe with the top sealed by a gloved finger, into which a plunger was then inserted. The syringe was inverted, and excess air was pushed out of it. The top of the syringe was sealed again by a gloved finger, after which negative pressure was applied several times. The infiltration usually took less than 20 s. The infiltrated leaves were immersed in the fixative for 1 h in the dark at room temperature. After washing with PBS, leaves were incubated three to four times for 20 min each with pure methanol at 37°C to remove chlorophyll. Then, central areas of the leaves without the midrib were cut out and incubated with xylene for 2 min at 37°C, pure ethanol for 5 min at room temperature, and 50% (v/v; in PBS) ethanol for 5 min at room temperature and washed with Milli-Q water twice. Materials were mounted on MAS-coated microscope slides (Matsunami) in an orientation in which the abaxial side of the leaf was attached to the slide. Rehydrated samples were digested with 1% (w/v) Cellulase Onozuka R-10 (Yakult) with 0.5% (w/v) Macerozyme R-10 (Yakult) in PBS for 1 h at 37°C. After digestion, all of the leaf tissue except for the abaxial epidermis attached to the slide was removed stereomicroscopically in PBS, and the epidermal tissue left on the slide was washed four times for 5 min each with PBS. The epidermis was permeabilized with 3% (v/v) IGEPAL CA-630 (MP Biomedicals) with 10% (v/v) DMSO in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, samples were incubated with blocking solution (3% [w/v] BSA fraction V [Gibco] in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. The primary antiserum (anti-pThr or anti H+-ATPase) at a dilution of 1:3,000 in the blocking solution was applied overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG [Invitrogen; A11034]) at a dilution of 1:500 in the blocking solution was applied for 3 h at 37°C. The specimens were covered by a cover glass with 50% (v/v) glycerol.

Immunohistochemical Detection of PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells Using Isolated Epidermal Tissue

We performed immunohistochemical analyses (Hayashi et al., 2011) with slight modifications as described below. Epidermal tissue was fixed using 4% (w/v) formaldehyde with 0.1% (w/w) glutaraldehyde in MTSB for 2 h at 4°C in the dark. After washing, chlorophyll was removed by incubation with pure methanol for 10 min at 37°C. The epidermal tissue was digested with supernatant of 3% (w/v) Driselase (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.5% (w/v) Macerozyme R-10 in PBS for 45 min at 37°C. Tissue permeabilization was performed with 3% (w/w) Triton X-100 in PBS. Primary antiserum was applied overnight at 4°C. Other conditions (i.e. blocking and secondary antibody) were as described above.

Estimation of Phosphorylation Level or Amount of PM H+-ATPase in Guard Cells

Phosphorylation level or amount of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells was estimated based on Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescence intensity. Fluorescence images were obtained as described previously at the same exposure time within independent measurements (Hayashi et al., 2011). The fluorescence intensity of a pair of guard cells was measured using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health; Schneider et al., 2012) as described below. All images were split into red, green, and blue channels using the RGB stack command. The fluorescence intensity of each pair of guard cells was defined as the difference between the mean gray value of the guard cells on the green channel and that of the neighboring area without guard cells. The representative value of each specimen in an independent measurement was calculated as the geometric mean of more than 30 pairs of guard cells from at least two leaves. In each measurement, an additional specimen, in which normal serum was used instead of primary antiserum, was examined simultaneously. The net fluorescence intensity was defined as the difference between the representative values obtained for each antiserum and normal serum and is expressed relative to the corresponding control. Data represent arithmetic means of the relative values from at least three independent measurements with sd. Red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells was confirmed by a blind test (Supplemental Fig. S9A).

Measurement of Stomatal Aperture

Isolated epidermal tissue was collected from a 58-µm nylon mesh and observed microscopically. To measure the stomatal aperture in whole leaves, the leaves were collected after the treatments and blended as described above, with the exception of ht1-9 and cbc1 cbc2; then, isolated epidermis samples were collected and observed immediately. Because a high concentration of extracellular K+ keeps stomata open in isolated epidermis samples of cbc1 cbc2 (Hiyama et al., 2017), leaves from cbc1 cbc2, ht1-9, a mutant of the component upstream of CBC1 and CBC2, and control Col-0 plants were blended in potassium buffer (5 mm MES-1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino] propane [pH 6.5] and 50 mm KCl) to prevent possible stomatal closure, and isolated epidermis samples were observed immediately with the same solution, as shown in Supplemental Figure S7. The representative value of each specimen in an independent measurement was calculated as the arithmetic mean of 30 stomatal apertures on the abaxial side (five stomata per epidermis) from at least two leaves. Data represent arithmetic means of the absolute mean values from at least three independent measurements with sd. Red light-induced stomatal opening was confirmed by a blind test (Supplemental Fig. S9B).

Statistical Analyses

For means expressed as relative values, one-tailed or two-tailed one-sample Student’s t tests were carried out to evaluate whether the mean was statistically significantly different from a corresponding control set to 1. Whether there was a difference between two independent means was assessed using one-tailed or two-tailed Student’s t test. For means expressed as absolute values, statistically significant increases in multiple means compared with a single control were assessed using a one-tailed Dunnett’s test. Statistically significant differences among all means were analyzed using Tukey’s test. P values were calculated using R (version 3.4.4; R Core Team, 2018) with the package multcomp (version 1.4.8; Hothorn et al., 2008), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under the following accession numbers: GL1 (At3g27920), PHOT1 (At3g45780), PHOT2 (At5g58140), AHA1 (At2g18960), AHA2 (At4g30190), PHYA (At1g09570), PHYB (At2g18790), HT1 (At1g62400), CBC1 (At3g01490), and CBC2 (At5g50000).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Validation of red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells in whole leaves.

Supplemental Figure S2. Light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells and stomatal opening in isolated epidermis.

Supplemental Figure S3. Inhibition of blue light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells in whole leaves by ABA but not DCMU.

Supplemental Figure S4. Immunohistochemical detection of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells in whole leaves from Landsberg erecta and phyA phyB.

Supplemental Figure S5. Schematic diagram of the setup for the aeration experiment.

Supplemental Figure S6. Effects of incubation solution on red light-induced phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase in guard cells in isolated epidermis.

Supplemental Figure S7. Light-induced stomatal opening in whole leaves from Col-0, ht1-9, and cbc1 cbc2.

Supplemental Figure S8. Schematic diagram of the possible model for light-induced stomatal opening in whole leaves mediated by PM H+-ATPase in guard cells.

Supplemental Figure S9. Blind tests of red light responses.

Dive Curated Terms

The following phenotypic, genotypic, and functional terms are of significance to the work described in this paper:

Acknowledgments

We thank Yukari Kamiya and Dr. Maki Hayashi for technical assistance and advice in the establishment of the immunohistochemical technique using whole leaves, Dr. Koji Takahashi for participation in the blind test of the immunohistochemical analysis of the phosphorylation level of PM H+-ATPase and stomatal aperture measurement, and Drs. Ken-ichiro Shimazaki and Shin-ichiro Inoue for critical advice on this study.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (grant nos. 15H05956 and 15H04386 to T.K.), and by a Grant-in-Aid for Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Research Fellow (grant no. 26303 to E.A.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Ando E, Ohnishi M, Wang Y, Matsushita T, Watanabe A, Hayashi Y, Fujii M, Ma JF, Inoue S, Kinoshita T (2013) TWIN SISTER OF FT, GIGANTEA, and CONSTANS have a positive but indirect effect on blue light-induced stomatal opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 162: 1529–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brearley J, Venis MA, Blatt MR (1997) The effect of elevated CO2 concentration on K+ and anion channels of Vicia faba L. guard cells. Planta 203: 145–154 [Google Scholar]

- Cominelli E, Galbiati M, Vavasseur A, Conti L, Sala T, Vuylsteke M, Leonhardt N, Dellaporta SL, Tonelli C (2005) A guard-cell-specific MYB transcription factor regulates stomatal movements and plant drought tolerance. Curr Biol 15: 1196–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daloso DM, Dos Anjos L, Fernie AR (2016) Roles of sucrose in guard cell regulation. New Phytol 211: 809–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi M, Shimazaki K (2008) The stomata of the fern Adiantum capillus-veneris do not respond to CO2 in the dark and open by photosynthesis in guard cells. Plant Physiol 147: 922–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi M, Shigenaga A, Emi T, Kinoshita T, Shimazaki K (2004) A transgene encoding a blue-light receptor, phot1, restores blue-light responses in the Arabidopsis phot1 phot2 double mutant. J Exp Bot 55: 517–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A, Bowling DJF (1985) Evidence for a CO2 inhibited proton extrusion pump in the stomatal cells of Tradescantia virginiana. J Exp Bot 36: 91–98 [Google Scholar]

- Falhof J, Pedersen JT, Fuglsang AT, Palmgren M (2016) Plasma membrane H+-ATPase regulation in the center of plant physiology. Mol Plant 9: 323–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger D, Maierhofer T, Al-Rasheid KAS, Scherzer S, Mumm P, Liese A, Ache P, Wellmann C, Marten I, Grill E, et al. (2011) Stomatal closure by fast abscisic acid signaling is mediated by the guard cell anion channel SLAH3 and the receptor RCAR1. Sci Signal 4: ra32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruta M, Burch HL, Nelson RB, Barrett-Wilt G, Kline KG, Mohsin SB, Young JC, Otegui MS, Sussman MR (2010) Molecular characterization of mutant Arabidopsis plants with reduced plasma membrane proton pump activity. J Biol Chem 285: 17918–17929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Negi J, Young J, Israelsson M, Schroeder JI, Iba K (2006) Arabidopsis HT1 kinase controls stomatal movements in response to CO2. Nat Cell Biol 8: 391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Inoue S, Takahashi K, Kinoshita T (2011) Immunohistochemical detection of blue light-induced phosphorylation of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase in stomatal guard cells. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 1238–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Nakamura S, Takemiya A, Takahashi Y, Shimazaki K, Kinoshita T (2010) Biochemical characterization of in vitro phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 1186–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyama A, Takemiya A, Munemasa S, Okuma E, Sugiyama N, Tada Y, Murata Y, Shimazaki KI (2017) Blue light and CO2 signals converge to regulate light-induced stomatal opening. Nat Commun 8: 1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hõrak H, Sierla M, Tõldsepp K, Wang C, Wang YS, Nuhkat M, Valk E, Pechter P, Merilo E, Salojärvi J, et al. (2016) A dominant mutation in the HT1 kinase uncovers roles of MAP kinases and GHR1 in CO2-induced stomatal closure. Plant Cell 28: 2493–2509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrer D, Flütsch S, Pazmino D, Matthews JS, Thalmann M, Nigro A, Leonhardt N, Lawson T, Santelia D (2016) Blue light induces a distinct starch degradation pathway in guard cells for stomatal opening. Curr Biol 26: 362–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P (2008) Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J 50: 346–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao TC, Allaway WG, Evans LT (1973) Action spectra for guard cell Rb+ uptake and stomatal opening in Vicia faba. Plant Physiol 51: 82–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue SI, Kinoshita T (2017) Blue light regulation of stomatal opening and the plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Plant Physiol 174: 531–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezek M, Blatt MR (2017) The membrane transport system of the guard cell and its integration for stomatal dynamics. Plant Physiol 174: 487–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Shimazaki K (1999) Blue light activates the plasma membrane H+-ATPase by phosphorylation of the C-terminus in stomatal guard cells. EMBO J 18: 5548–5558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Shimazaki K (2001) Analysis of the phosphorylation level in guard-cell plasma membrane H+-ATPase in response to fusicoccin. Plant Cell Physiol 42: 424–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Shimazaki K (2002) Biochemical evidence for the requirement of 14-3-3 protein binding in activation of the guard-cell plasma membrane H+-ATPase by blue light. Plant Cell Physiol 43: 1359–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Doi M, Suetsugu N, Kagawa T, Wada M, Shimazaki K (2001) Phot1 and phot2 mediate blue light regulation of stomatal opening. Nature 414: 656–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriedemann PE, Loveys BR, Downton WJS (1975) Internal control of stomatal physiology and photosynthesis. II. Photosynthetic responses to phaseic acid. Aust J Plant Physiol 2: 553–567 [Google Scholar]

- Lauer MJ, Boyer JS (1992) Internal CO2 measured directly in leaves: abscisic acid and low leaf water potential cause opposing effects. Plant Physiol 98: 1310–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T. (2009) Guard cell photosynthesis and stomatal function. New Phytol 181: 13–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Lefebvre S, Baker NR, Morison JIL, Raines CA (2008) Reductions in mesophyll and guard cell photosynthesis impact on the control of stomatal responses to light and CO2. J Exp Bot 59: 3609–3619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P, Outlaw WH Jr, Smith BG, Freed GA (1997) A new mechanism for the regulation of stomatal aperture size in intact leaves: accumulation of mesophyll-derived sucrose in the guard-cell wall of Vicia faba. Plant Physiol 114: 109–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrosova A, Bogireddi H, Mateo-Peñas A, Hashimoto-Sugimoto M, Iba K, Schroeder JI, Israelsson-Nordström M (2015) The HT1 protein kinase is essential for red light-induced stomatal opening and genetically interacts with OST1 in red light and CO2-induced stomatal movement responses. New Phytol 208: 1126–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawson BT, Colman B, Cummins WR (1981) Abscisic acid and photosynthesis in isolated leaf mesophyll cell. Plant Physiol 67: 233–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzella MA, Alconada Magliano TM, Casal JJ (1997) Dual effect of phytochrome A on hypocotyl growth under continuous red light. Plant Cell Environ 20: 261–267 [Google Scholar]

- Messinger SM, Buckley TN, Mott KA (2006) Evidence for involvement of photosynthetic processes in the stomatal response to CO2. Plant Physiol 140: 771–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott KA. (1988) Do stomata respond to CO2 concentration other than intercellular? Plant Physiol 86: 200–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott KA. (2009) Opinion: stomatal responses to light and CO2 depend on the mesophyll. Plant Cell Environ 32: 1479–1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott KA, Sibbernsen ED, Shope JC (2008) The role of the mesophyll in stomatal responses to light and CO2. Plant Cell Environ 31: 1299–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura M, Inoue S, Kuwata K, Kinoshita T (2016) Photosynthesis activates plasma membrane H+-ATPase via sugar accumulation. Plant Physiol 171: 580–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RL, Pratt B, Gump P, Kemper A, Tallman G (2002) Red light activates a chloroplast-dependent ion uptake mechanism for stomatal opening under reduced CO2 concentrations in Vicia spp. New Phytol 153: 497–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poffenroth M, Green DB, Tallman G (1992) Sugar concentrations in guard cells of Vicia faba illuminated with red or blue light: analysis by high performance liquid chromatography. Plant Physiol 98: 1460–1471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2018) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna [Google Scholar]

- Roelfsema MRG, Steinmeyer R, Staal M, Hedrich R (2001) Single guard cell recordings in intact plants: light-induced hyperpolarization of the plasma membrane. Plant J 26: 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfsema MRG, Hanstein S, Felle HH, Hedrich R (2002) CO2 provides an intermediate link in the red light response of guard cells. Plant J 32: 65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfsema MRG, Konrad KR, Marten H, Psaras GK, Hartung W, Hedrich R (2006) Guard cells in albino leaf patches do not respond to photosynthetically active radiation, but are sensitive to blue light, CO2 and abscisic acid. Plant Cell Environ 29: 1595–1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelia D, Lunn JE (2017) Transitory starch metabolism in guard cells: unique features for a unique function. Plant Physiol 174: 539–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer M, Paciorek T, Benková E, Friml J (2006) Immunocytochemical techniques for whole-mount in situ protein localization in plants. Nat Protoc 1: 98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz A, Zeiger E (1984) Metabolic energy for stomatal opening: roles of photophosphorylation and oxidative phosphorylation. Planta 161: 129–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano EE, Zeiger E, Hagiwara S (1988) Red light stimulates an electrogenic proton pump in Vicia guard cell protoplasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 436–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Raschke K (1981) Effect of light quality on stomatal opening in leaves of Xanthium strumarium L. Plant Physiol 68: 1170–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki K, Doi M, Assmann SM, Kinoshita T (2007) Light regulation of stomatal movement. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58: 219–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suetsugu N, Takami T, Ebisu Y, Watanabe H, Iiboshi C, Doi M, Shimazaki K (2014) Guard cell chloroplasts are essential for blue light-dependent stomatal opening in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 9: e108374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Jin X, Albert R, Assmann SM (2014) Multi-level modeling of light-induced stomatal opening offers new insights into its regulation by drought. PLOS Comput Biol 10: e1003930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbott LD, Zeiger E (1993) Sugar and organic acid accumulation in guard cells of Vicia faba in response to red and blue light. Plant Physiol 102: 1163–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AR, Assmann SM (2001) Apparent absence of a redox requirement for blue light activation of pump current in broad bean guard cells. Plant Physiol 125: 329–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Kinoshita T, Shimazaki K (2001) Guard-cell chloroplasts provide ATP required for H+ pumping in the plasma membrane and stomatal opening. Plant Cell Physiol 42: 795–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno K, Kinoshita T, Inoue S, Emi T, Shimazaki K (2005) Biochemical characterization of plasma membrane H+-ATPase activation in guard cell protoplasts of Arabidopsis thaliana in response to blue light. Plant Cell Physiol 46: 955–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahisalu T, Kollist H, Wang YF, Nishimura N, Chan WY, Valerio G, Lamminmäki A, Brosché M, Moldau H, Desikan R, et al. (2008) SLAC1 is required for plant guard cell S-type anion channel function in stomatal signalling. Nature 452: 487–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang FF, Lian HL, Kang CY, Yang HQ (2010) Phytochrome B is involved in mediating red light-induced stomatal opening in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant 3: 246–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SW, Li Y, Zhang XL, Yang HQ, Han XF, Liu ZH, Shang ZL, Asano T, Yoshioka Y, Zhang CG, et al. (2014a) Lacking chloroplasts in guard cells of crumpled leaf attenuates stomatal opening: both guard cell chloroplasts and mesophyll contribute to guard cell ATP levels. Plant Cell Environ 37: 2201–2210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Noguchi K, Terashima I (2011) Photosynthesis-dependent and -independent responses of stomata to blue, red and green monochromatic light: differences between the normally oriented and inverted leaves of sunflower. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 479–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Papanatsiou M, Eisenach C, Karnik R, Williams M, Hills A, Lew VL, Blatt MR (2012) Systems dynamic modeling of a guard cell Cl− channel mutant uncovers an emergent homeostatic network regulating stomatal transpiration. Plant Physiol 160: 1956–1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Noguchi K, Ono N, Inoue S, Terashima I, Kinoshita T (2014b) Overexpression of plasma membrane H+-ATPase in guard cells promotes light-induced stomatal opening and enhances plant growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 533–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue S, Hu H, Ries A, Merilo E, Kollist H, Schroeder JI (2011) Central functions of bicarbonate in S-type anion channel activation and OST1 protein kinase in CO2 signal transduction in guard cell. EMBO J 30: 1645–1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi S, Takemiya A, Sakamoto T, Kurata T, Tsutsumi T, Kinoshita T, Shimazaki K (2016) The plasma membrane H+-ATPase AHA1 plays a major role in stomatal opening in response to blue light. Plant Physiol 171: 2731–2743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiger E. (1983) The biology of stomatal guard cells. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 34: 441–475 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wang H, Takemiya A, Song CP, Kinoshita T, Shimazaki K (2004) Inhibition of blue light-dependent H+ pumping by abscisic acid through hydrogen peroxide-induced dephosphorylation of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase in guard cell protoplasts. Plant Physiol 136: 4150–4158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]