Abstract

Many chemicals that disrupt endocrine function have been linked to a variety of adverse biological outcomes. However, screening for endocrine disruption using in vitro or in vivo approaches is costly and time-consuming. Computational methods, e.g. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship models, have become more reliable due to bigger training sets, increased computing power, and advanced machine learning algorithms such as multi-layered Artificial Neural Networks. Machine learning models can be used to predict compounds for endocrine disrupting capabilities such as binding to the estrogen receptor (ER) and allow for prioritization and further testing. In this work an exhaustive comparison of multiple machine learning algorithms, chemical spaces, and evaluation metrics for ER binding was performed on public datasets curated using in-house cheminformatics software (Assay Central). Chemical features utilized in modeling consisted of binary fingerprints (ECFP6, FCFP6, ToxPrint or MACCS keys) and continuous molecular descriptors from RDKit. Each feature set was subjected to classic machine learning algorithms (Bernoulli Naive Bayes, AdaBoost Decision Tree, Random Forest, Support Vector Machine) and deep neural networks (DNN). Models were evaluated using a variety of metrics: Recall, Precision, F1-Score, Accuracy, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve, Cohen’s Kappa, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient. For predicting compounds within the training set, DNN has higher Accuracy than other methods; however, in five-fold cross validation and external test set predictions, DNN and most classic machine learning models perform similarly regardless of dataset or molecular descriptors used. We have also used the rank normalized scores as a performance-criteria for each machine learning method and Random Forest performed best on the evaluation set when ranked by metric or by datasets. These results suggest classic machine learning algorithms may be sufficient to develop high quality predictive models of ER activity.

Keywords: Bayesian, Deep Learning, Estrogen Receptor, Machine learning, Support Vector Machine

TABLE OF CONTENTS GRAPHIC

INTRODUCTION

Estrogen receptors (ERs) are cellular proteins that trigger the expression of gene products crucial to the endocrine system1. There are nuclear ERs as well as orphan nuclear receptors like the estrogen related receptors 2 and membrane ERs 3. The two unique nuclear ERs, ERα and ERβ, are highly similar in their DNA binding domains and share 53% sequence identity in their ligand binding domains, so while many ligands interact with both receptors others are specific 4. Interestingly, amongst all known ER binding agents, the ERα binders are better characterized than ERβ binders5. Aside from binding to standard ER ligands, these receptors can be activated by certain endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDC), resulting in altered ER signaling5. A growing body of evidence suggests that both natural and manufactured chemicals may therefore bind to ERs and produce adverse effects in laboratory and wildlife animals, as well as humans6. Epidemiological studies suggest that there may be a link between exposure to EDCs and breast cancer risk, among other factors including heredity and lifestyle7, 8. The potential ER binding of new drug candidates and consumer products is an important public health concern and must be considered during chemical research and development.

Previously there have been many traditional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling studies focused on small sets of ER ligands from mouse 9–11 as well as studies aiming to identify EDCs12–14, several of which have resulted in commercial ER models distributed as part of chemical toxicity assessment tools such as Leadscope15, Lhasa16 and Case Ultra17. These commercial tools are based on QSAR approaches or other chemical structural methods that have not changed for many years and do not make use of the more recent bigger data sources and algorithms being applied to ER data18–20. Thus, it is critical to develop novel techniques that could take advantage of public big data (i.e. automatic data mining, curation, management and modeling) to study complicated biological phenomena such as ER binding21–23. There are many machine learning algorithms available for such efforts. Artificial neural networks (ANN) may offer a solution, and several comparisons of different machine learning methods have been undertaken. Deep neural networks (DNNs) with multitask learning24 slightly outperformed the closest consensus ANN method25 across nuclear receptor and stress response datasets previously. We have recently compared several different machine learning approaches and found that DNN outperformed them all when the data was ranked by either metric or dataset during cross validation26.

We have utilized in-house software called Assay Central 27, that leverages our work on making molecule fingerprints and machine learning algorithms publicly available 28–30 for Bayesian machine learning of ER activity. Additional machine learning algorithms have also been evaluated for potential inclusion in Assay Central, specifically DNNs, which have won several contests in pattern recognition and machine learning31–33 and have been reviewed for their application in pharmaceutical research34–37. The aim of this study therefore was to compare classic and DNN machine learning algorithms for different ER datasets and identify the most appropriate models for making predictions for new compounds.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Datasets and Descriptors

While there are a small number of ligand datasets for orphan nuclear receptors 2 and membrane ER datasets 3 (e.g. CHEMBL3429, CHEMBL3751, CHEMBL4245, CHEMBL5872) these are currently much smaller than for ERα and ERβ. Eight ER training datasets were curated with Assay Central workflows (see next section) stemming from different sources and endpoints (i.e. Ki, IC50, binary active/inactive) and are outlined in Table 1; the outputs of these training data were utilized as inputs for all machine learning methods (Supplemental Data 1). All quantitative endpoints were converted using a method for determining the optimal threshold cutoff for active and inactive compounds, described in a previous paper38. For qualitative endpoints, the classification established by the source was used (i.e. the PubChem active agonist/antagonist classification for Tox21 datasets and the EPA classification of active agonist/antagonist/binder for CERAPP dataset).

Table 1.

Estrogen receptor datasets used in this study. Several of the datasets have been previously described 46, 56.

| Dataset Name | Original Endpoint | Threshold | Source | Target Receptor | ChEMBL assay ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha Binding IC50 | IC50 | 3.62 μM | ChEMBL | ER Alpha | 676818, 679323, 679891, 682290, 829337, 831077, 831155, 831528, 831661, 832786, 833547, 873603, 881884, 1614199, 829540, 865582, 1114100, 860989, 868001, 852960, 3429911, 679891 |

| Alpha Binding Ki V2 | Ki | 687.07 nM | ChEMBL | ER Alpha | 682301, 3591297, 839531 + ChEMBL autobuild from TargetID 206 |

| Alpha Tox21 Bg1 Agonist V2 | Source supplied qualitative (active/inactive) | Pubchem | ER Alpha | AID 743091 | |

| Alpha Tox21 Bg1 Antagonist V2 | Source supplied qualitative (active/inactive) | PubChem | ER Alpha | AID 743091 | |

| Beta Binding IC50 Only | IC50 | 1.140 μM | ChEMBL | ER Beta | 677050, 678095, 682167, 682168, 827158, 831372, 831659, 832634, 832843, 880931, 1114099, 831137, 1614359, 865583, 860987, 868002, 852961, 859108, 830924, 831662 |

| Beta Binding Ki V2 | Ki | 281.19 nM | ChEMBL | ER Beta | 3591298, 838887, 839524 + ChEMBL autobuild from TargetID 242 |

| CERAPP Agonist | Source supplied qualitative (active/inactive) | EPA | ER Alpha | 46 | |

| CERAPP Antagonist | Source supplied qualitative (active/inactive) | EPA | ER Alpha | 46 |

We explored a variety of feature spaces in this project including several types of chemical fingerprints and molecular descriptors. Extended connectivity fingerprints (ECFP) are circular topological fingerprints generated by applying the Morgan algorithm and have widely been noted for their ability to map structure-activity relationships2. Additionally, the feature-based version of the ECFP fingerprints (FCFP), which switches atom properties (i.e. atomic number, charge) for feature definitions (i.e. hydrogen bond donor, acceptor), were used. Molecular ACCess System (MACCS) keys are 166 substructure definitions and have widely been used in QSAR modeling and similarity searches39. The final fingerprint used in this study was calculated using ChemoTyper (https://chemotyper.org/)40 which allows for the identification of chemical substructures based upon a set of rules. We used the ToxPrint (https://toxprint.org/) chemotypers which are a publicly available set of substructures relevant to toxicity. Molecular descriptors were generated from the cheminformatics library RDKit (www.rdkit.org) and comprised of 196 2D and 3D chemical properties that can be topological, compositional, electrotopological state, etc.

Assay Central

The Assay Central project uses the source code management system Git to gather and store molecular datasets from diverse sources, in addition to scripts for curating well-defined structure-activity datasets. These scripts employ a series of rules for the detection of problem data that is corrected by a combination of automated structure standardization including removing salts, neutralizing unbalanced charges, and merging duplicate structures with finite activities and human re-curation. Questionable structures were checked for accuracy against common, reliable resources such as CompTox (https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard), ChemSpider (http://www.chemspider.com/), and the Merck Index (https://www.rsc.org/merck-index). The output is a high-quality dataset and a Bayesian model which can be conveniently used to predict activities for proposed compounds. Each model in Assay Central includes the following metrics defined in the Data Analysis section, for evaluative predictive performance: Recall, Precision, Specificity, F1-Score, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, Cohen’s Kappa (CK), and the Matthews Correlation Constant (MCC). We utilized Assay Central to prepare and merge datasets collated in Molecular Notebook41, as well as generate Bayesian models of either training data alone or combined with testing data, using the ECFP6 descriptor 38, 42 (Supplemental Data 2 and 3).

Assay Central prediction workflows assign a probability score and applicability domain to the input compounds according to a user-specified model. Compounds present in the training set (including tautomers) were removed from the output. Predictions were carried out as a part of the curation of an external testing set defined in the Evaluation Set section.

Other Machine Learning Methods

Regardless of feature space or machine learning algorithm, all datasets were processed in the same manner. First, compounds within a dataset were randomized and 20% of the compounds were left out for an external validation set in a stratified manner so as to maintain active and inactive proportions. Then, model parameters were identified during training by using a five-fold stratified cross validation method as implemented in the machine learning package scikit-learn (http://scikit-learn.org/stable/). The training set compounds were used in training by either of two sets of machine learning algorithms. 1) Classic Machine Learning (CML) algorithms all available within scitkit-learn (Bernoulli Naive Bayes, AdaBoost Decision Tree, Random Forest, or Support Vector Machines), or 2) DNN models of different complexity using the deep learning library Keras (https://keras.io/), and theano (http://deeplearning.net/software/theano/ for GPU training and CPU for prediction) as a backend. More information on these machine learning algorithms as well as their hyperparameters has been described previously26.

Data Analysis

In this study, several traditional measurements of model performance were used, including Recall, Precision, F1-Score, Accuracy, area under the ROC curve (AUC), Cohen’s Kappa43, 44, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient45. For the metric definitions, we will use the following abbreviations: the number of true positives (TP), the number of false positives (FP), the number of true negatives (TN), and the number of false negatives (FN) classified during five-fold cross-validation. Specificity or the TN rate is defined by the percentage of false class labels correctly identified by five-fold cross validation, . Model Recall also known as Sensitivity, or the True Positive Rate (TPR), is the percentage of positive class labels (i.e. compound is active at a target) correctly identified by the model out of the total number of actual positives and is defined: . Precision also known as the Positive Predictive Value is the percentage of positive class labels correctly identified out of total predicted positives and is defined: . The F1-Score is simply the harmonic mean of the Recall and Precision: . The ROC curve can be computed by first plotting the TPR versus the False Positive Rate (FPR) at various decision thresholds, T where . All constructed models are capable of assigning a probability estimate of a sample belonging to the positive class. The TPR and FPR performance is measured when we consider a sample with a probability estimate > T as being true for various intervals between 0 and 1. The AUC can be calculated from this plot and can be interpreted as the ability of the model to separate classes, where 1 denotes perfect separation and 0.5 is random classification. Accuracy is the percentage of correctly identified labels (TP and TN) out of the entire population: . Cohen’s Kappa (CK), attempts to leverage the Accuracy by normalizing it to the probability that the classification would agree by chance (pe) and is calculated by , where .. Another measure of overall model classification performance is Matthews Correlation Coefficient45 (MCC), defined as ; MCC is not subject to heavily imbalanced classes and its value can be between −1 and 1.

To illustrate a comprehensive picture of overall model robustness we obtained a rank normalized metric by first range-scaling all metrics to [0, 1] and taking the mean.

Principal Component Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a dimension-reduction technique to reduce the high-dimensional feature sets to 3 or 2 dimensions and aids in visualization. To assess the applicability domain of the in vitro data for the different datasets we used PCA algorithm available within scikit-learn to reduce the dimensions of the ECFP6 fingerprints to 3 for plotting purposes.

Evaluation Set

For a final performance evaluation, we downloaded a large evaluation set curated and made available by the EPA46. This dataset consists of in vitro experimental ER data from a variety of sources including Tox21, the US FDA Estrogenic Activity Database, METI (Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry) database, and ChEMBL. Originally, this set consisted of 20,141 entries describing ER antagonism, agonism, or general binding for 7,522 unique chemical structures. In this study we focused on general binding. If a compound contained multiple AC50 values culled from different studies, the mean across all values was taken. We further curated this evaluation set by eliminating all compounds constituting any of our eight training datasets using Assay Central prediction workflows. The final curated evaluation set consisted of 227 unique compounds with AC50 values ranging from 0.00001 μM to 1000000 μM (Supplemental Data 1).

Because models from the eight ER training datasets were built from different endpoints (Ki, IC50, qualitative) predictions needed to be processed differently for each dataset. Datasets stemming from IC50 or Ki values, applied the threshold of that particular model to the AC50 values in the evaluation set (i.e., considered Ki = AC50 = IC50). Datasets with qualitative information (Tox21/CERAPP) used the classification of potency provided by the EPA (AC50 <= 0.01 μM)46.

RESULTS

Dataset Analysis

Supplemental Figure 1 shows that some datasets are clearly balanced (e.g. ERα IC50, ERβ IC50) whereas others are not (e.g. CERAPP, Tox21). These datasets also vary in their intra-dataset Tanimoto similarity (Supplemental Figure 2) and several related groups cluster in their inter-dataset similarity for actives and inactives (Supplemental Figure 3). PCA was used to visualize the chemical property space of active and inactive compounds in an individual training set versus all datasets herein. Supplemental Figure 4 shows that some of these datasets also have good overlap of active and inactive compounds (i.e. Tox21, CERAPP) whereas for others this was only partial (i.e. ChEMBL).

Assay Central Internal Validation

We identified multiple ER datasets from different sources that we used to create multiple Bayesian models ranging from 969 to 7351 total compounds (Tables 1 and 2). Five-fold cross validation yielded ROC values from 0.63–0.97, indicating reasonable to excellent predictivity, while other metrics like F1-Score (0.09–0.94), Cohen’s Kappa (0.05–0.87), and Matthew’s Correlation Coefficient (0.09–0.87) varied greatly (Table 2, Supplemental Figure 5). Using these metrics, dataset imbalance and different chemical space coverage does not appear to adversely affect the model robustness.

Table 2.

Summary of ER data and Bayesian Models from Assay Central following five-fold cross validation.

| Dataset Name | Size | ROC | F1 | Kappa | MCC | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CERAPP Agonist | 1677 | 0.77 | 0.42 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.28 |

| CERAPP Antagonist | 1677 | 0.63 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.28 |

| Tox21 Agonists | 7351 | 0.84 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.38 |

| Tox21 Antagonists | 7351 | 0.76 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.38 |

| Alpha (Bind/IC50) | 1127 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.26 |

| Alpha (Bind/Ki) | 2347 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.29 |

| Beta (Bind/IC50) | 969 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.26 |

| Beta (Bind/Ki) | 1806 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.26 |

Internal Validation of Different Machine Learning Algorithms

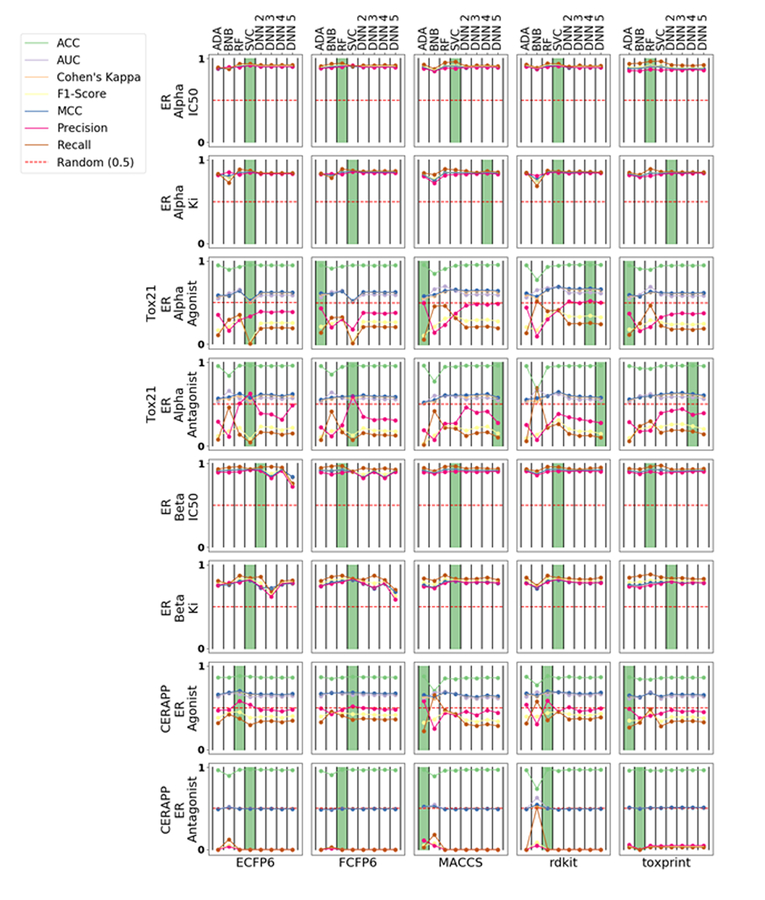

We compared multiple CML methods against DNNs with different numbers of layers and considered several descriptors including ECFP6, FCFP6, MACCS, RDKit and ToxPrint using five-fold cross validation of the training sets (Figure 1). RF and SVC perform optimally for ERα datasets and have little difference between descriptors for the metrics measured, but SVC performs the best for ERβ datasets in most cases. The Tox21 and CERAPP models provide variable performance across different descriptors; generally, these models have a high Accuracy and other statistics are lower, while ADA performed the best in most cases.

Figure 1.

Five-fold cross validation statistics for all eight datasets in this study organized by datasets (rows) and descriptors (columns). The green bar represents the best performing algorithm, measured by ACC, for a particular dataset-chemical space pair. All metrics were range scaled to [0, 1]. AdaBoost (ADA); Bernoulli Naïve-Bayes (BNB); Random Forest (RF); support vector classification (SVC); Deep Neural Networks (DNN).

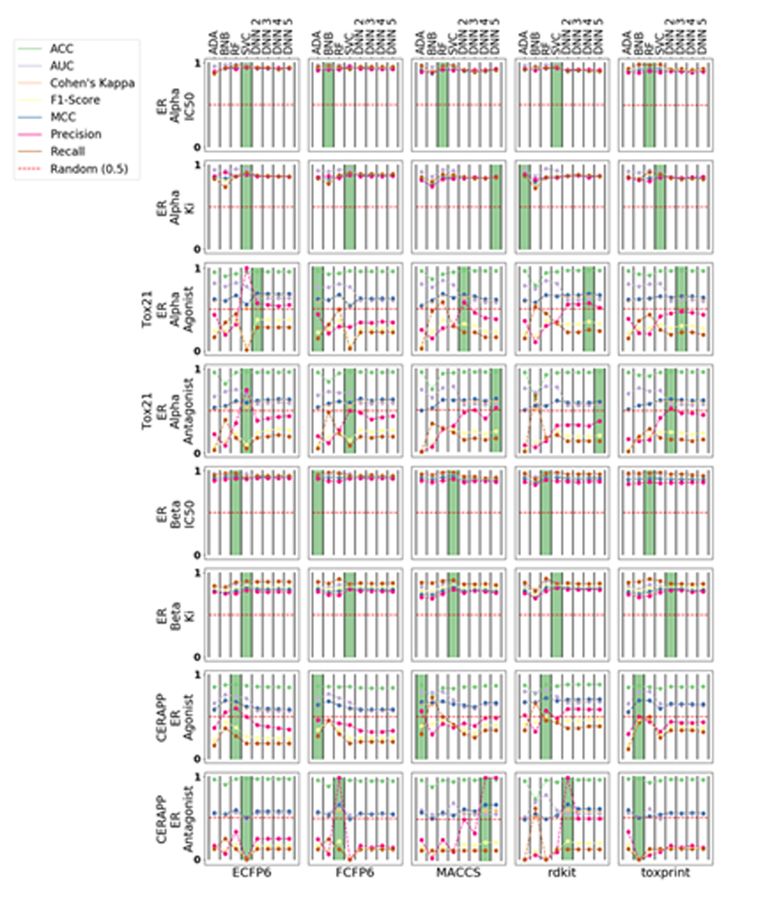

External Validation of Different Machine Learning Algorithms

We used a validation set of 20% of the compounds to externally evaluate the predictive capability of each model with the same metrics as the internal validation (Figure 2). External validation of ChEMBL-sourced ERα models does not suggest a clear winner across algorithms or descriptors, as all model metrics were tightly clustered. Several of the best-performing ERβ models were SVC, but again the metrics were similar across algorithms and descriptors. Our external validation of different ERα models suggested Bayesian models performed well for both ECFP6 and FCFP6 descriptors while ERβ models built with ECFP6 descriptors slightly out-performed the others. The CERAPP models provided variable metrics across different descriptors with no clear winner, but the best metrics for the Tox21 data were produced with DNNs. Both we26 and others47 have used the rank normalized scores26 as a performance criteria for each machine learning method. RF performed best when ranked by metric (Table 3) or by datasets (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Validation set statistics for all eight datasets in this study. AdaBoost (ADA); Bernoulli Naive Bayes (BNB); Random forest (RF); support vector classification (SVC); Deep Neural Networks (DNN).

Table 3.

Ranked normalized scores for each machine learning algorithm by metric (average over datasets for the validation dataset). AdaBoost (ADA); Bernoulli Naive Bayes (BNB); Random forest (RF); support vector classification (SVC); Deep Neural Networks (DNN).

| Algorithm | ACC | AUC | Cohen’s Kappa | F1-Score | MCC | Precision | Recall | Mean | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.58 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 1 |

| DNN 2 | 0.90 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 2 |

| SVC | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.74 | 0.61 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 3 |

| DNN 5 | 0.90 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 4 |

| DNN 4 | 0.90 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 5 |

| DNN 3 | 0.90 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 6 |

| BNB | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.54 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 7 |

| ADA | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.68 | 8 |

Table 4.

Ranked normalized scores of each machine learning algorithm by datasets (averaged over seven metrics for validation datasets).

| Algorithm | ERα IC50 | ERα Ki | Tox21 ERα Agonist |

Tox21 ERα Antagonist |

ERβ IC50 | ERβ Ki | CERAPP ER Agonist |

CERAPP ER Antagonist |

Mean | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.72 | 1 |

| DNN 2 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 2 |

| SVC | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.55 | 0.39 | 0.70 | 3 |

| DNN 5 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 4 |

| DNN 4 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 5 |

| DNN 3 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.70 | 6 |

| BNB | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 7 |

| ADA | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.68 | 8 |

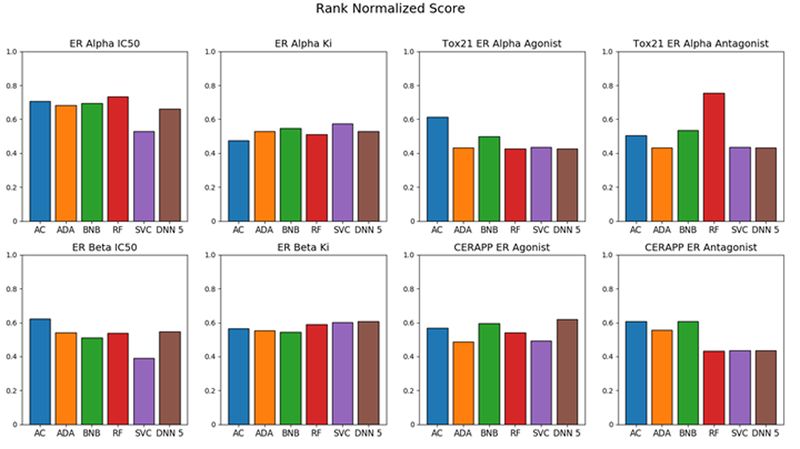

To further validate the models, we procured an evaluation set consisting of 227 molecules unique to all training sets in this study. Assay Central ranked best for the Tox21 ERα agonist, ERβ IC50, and CERAPP ER antagonist data while RF ranked highest for the Tox21 ERα antagonist and ERα IC50 data. DNN5 performed the best for ERβ Ki and CERAPP ER agonist datasets (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of Assay Central model with other machine learning algorithms using a rank normalized score for the evaluation set. Assay Central (AC); AdaBoost (ADA); Bernoulli Naïve-Bayes (BNB); Random Forest (RF); support vector classification (SVC); Deep Neural Networks (DNN).

DISCUSSION

The estrogen receptor has been widely studied in terms of its importance to human health and in recent years there have been many publications using various computational approaches and datasets13, 18, 19, 46, 48–56.

Machine learning methods have been applied to many datasets in pharmaceutical and toxicological research over the past decades to enable prospective prediction and potentially increase efficiency and minimize testing and costs34, 57, 58. While much has been done to popularize Bayesian models59–62 we have recently described how fingerprint type molecular descriptors paired with Bayesian methods can result in more publicly accessible models38, 42, 63 and we have since leveraged these to build Assay Central27, 64, 65. We are very keen to evaluate additional machine learning algorithms and descriptors which have been presented herein. There has also been a great deal of recent interest in the DNN approach36, 37, 66–74 for both single task, multitask machine learning73, 75 as well as drug-target interaction76 and beyond. DNN has received considerable attention in cheminformatics without thorough validation in our opinion34. Interestingly, in our previous work accessing several datasets using cross validation data and based on ranked normalized scores for the metrics, DNN ranked higher than SVM, which in turn was ranked higher than all the other machine learning methods26. Our results also suggested the importance of assessing DNNs to a much greater extent using multiple metrics with larger scale comparisons and prospective testing27. Others have also compared many machine learning approaches with different ChEMBL datasets using random split and temporal cross validation to show the superiority of DNN 77 or 5 fold cross validation and leave out 40% as a validation set78 The current study represents a further extension of these comparisons of CML methods with DNN but focused on ER datasets.

In the current study, we have made extensive use of five-fold cross validation which indicated that different descriptors show a similar pattern in terms of the resulting model statistics (Figure 1). Similarly, external validation (Figure 2) also showed that the different descriptors showed a similar pattern, with ECFP6 and FCFP6 fingerprints having higher accuracy. On the evaluation set, the Bayesian approach does very well (BNB) and Assay Central models performed in line with other CML methods (Figure 3). This suggests that the approach may be a good choice for creating and making models accessible in general. The current study is limited in that the ECFP6 descriptors used for Assay Central and the different machine learning methods were from different sources, i.e. CDK79, 80 and RDKit 81, however the differences between fingerprints should be minimal. It should also be noted that each model has slightly different cutoffs for active and inactive designations, and that we combined data from different laboratories (Table 1). Ideally data should come from a single group to minimize differences and error. However, our models and testing analyses suggest that good statistics can be obtained in the case of ER, regardless of the data source.

In this work an exhaustive comparison of multiple machine learning algorithms, chemical spaces, and evaluation metrics for ER binding was performed on numerous public datasets curated using in-house cheminformatics software, Assay Central. Chemical features were created with public tools, consisting of binary fingerprints and continuous molecular descriptors. Each feature set was subjected to either CML algorithms or DNNs of varying depth. Models were then evaluated using a variety of metrics, including five-fold cross validation which showed DNNs had a clear advantage for prediction within the training set over CML models (Supplemental Figure 6). However, this advantage diminished when predicting compounds in an external test set as assessed using the rank normalized score of the various metrics or datasets, which may be indicative of over-training and hence require further work to moderate this occurrence. Our results suggest that simpler methods like BNB and RF may be sufficient to generate viable predictions for these ER datasets. Further studies could evaluate quantitative and consensus predictions across these different machine learning models. Efforts towards building computational approaches such as CERAPP46 have enlisted many laboratories to enable prospective prediction46; while they presented the concept of consensus models, these predictions were not actually followed up with prospective in vitro testing.

In conclusion, classic machine learning methods present a reliable approach to prioritizing compounds for ER in vitro testing which could be used alongside other computational approaches13, 53.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Ashley Brinkman, Dr. Diedrich Bermudez, Dr. Frank Jones, Dr. Kelley McKissic and their colleagues at SC Johnson are gratefully acknowledged for their support and discussions on this project. Dr. Alexandru Korotcov and Mr. Valery Tkachenko are kindly acknowledged for assistance with Deep Learning.

Grant information

We kindly acknowledge NIH funding R43GM122196 “Centralized assay datasets for modelling support of small drug discovery organizations” from NIH/NIGMS from NIGMS.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- ADME/Tox

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion/Toxicology

- ABDT

AdaBoost

- ANN

Artificial Neural Networks

- AUC

area under the curve

- BNB

Bernoulli Naive Bayes

- CML

Classic Machine Learning

- DT

Decision Tree

- DNN

Deep Neural Networks

- EDCs

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals

- ER

Estrogen Receptor

- kNN

k-Nearest Neighbors

- QSAR

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships

- RF

Random Forest

- ROC

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- SVC

Support Vector Classification

- SVM

Support Vector Machines

Footnotes

Competing interests:

S.E. is owner, D.P.R. and K.M.Z., are employees and A.M.C is a consultant of Collaborations Pharmaceuticals Inc.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Supporting further details on the models, structures of public molecules and computational models are available. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall JM; Couse JF; Korach KS The multifaceted mechanisms of estradiol and estrogen receptor signaling. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, (40), 36869–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giguere V; Yang N; Segui P; Evans RM Identification of a new class of steroid hormone receptors. Nature 1988, 331, (6151), 91–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soltysik K; Czekaj P Membrane estrogen receptors - is it an alternative way of estrogen action? J Physiol Pharmacol 2013, 64, (2), 129–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Journe F; Body JJ; Leclercq G; Laurent G Hormone therapy for breast cancer, with an emphasis on the pure antiestrogen fulvestrant: mode of action, antitumor efficacy and effects on bone health. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2008, 7, (3), 241–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanle EK; Xu W Endocrine disrupting chemicals targeting estrogen receptor signaling: identification and mechanisms of action. Chem Res Toxicol 2011, 24, (1), 6–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinstreuer NC; Ceger PC; Allen DG; Strickland J; Chang X; Hamm JT; Casey WM A Curated Database of Rodent Uterotrophic Bioactivity. Environ Health Perspect 2016, 124, (5), 556–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takemura H; Sakakibara H; Yamazaki S; Shimoi K Breast cancer and flavonoids - a role in prevention. Curr Pharm Des 2013, 19, (34), 6125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodgers KM; Udesky JO; Rudel RA; Brody JG Environmental chemicals and breast cancer: An updated review of epidemiological literature informed by biological mechanisms. Environ Res 2018, 160, 152–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waller CL; Oprea TI; Chae K; Park HK; Korach KS; Laws SC; Wiese TE; Kelce WR; Gray LE Jr. Ligand-based identification of environmental estrogens. Chem Res Toxicol 1996, 9, (8), 1240–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waller CL A comparative QSAR study using CoMFA, HQSAR, and FRED/SKEYS paradigms for estrogen receptor binding affinities of structurally diverse compounds. J Chem Inf Comput Sci 2004, 44, (2), 758–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waller CL; Minor DL; McKinney JD Using three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationships to examine estrogen receptor binding affinities of polychlorinated hydroxybiphenyls. Environ Health Perspect 1995, 103, (7–8), 702–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asikainen AH; Ruuskanen J; Tuppurainen KA Performance of (consensus) kNN QSAR for predicting estrogenic activity in a large diverse set of organic compounds. SAR QSAR Environ Res 2004, 15, (1), 19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L; Sedykh A; Tripathi A; Zhu H; Afantitis A; Mouchlis VD; Melagraki G; Rusyn I; Tropsha A Identification of putative estrogen receptor-mediated endocrine disrupting chemicals using QSAR-and structure-based virtual screening approaches. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2013, 272, (1), 67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki T; Ide K; Ishida M; Shapiro S Classification of environmental estrogens by physicochemical properties using principal component analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis. J Chem Inf Comput Sci 2001, 41, (3), 718–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leadscope. www.leadscope.com/product_info.php?products_id=78.

- 16.Mombelli E An evaluation of the predictive ability of the QSAR software packages, DEREK, HAZARDEXPERT and TOPKAT, to describe chemically-induced skin irritation. Altern Lab Anim 2008, 36, (1), 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MultiCASE. www.multicase.com.

- 18.Sakkiah S; Selvaraj C; Gong P; Zhang C; Tong W; Hong H Development of estrogen receptor beta binding prediction model using large sets of chemicals. Oncotarget 2017, 8, (54), 92989–93000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niu AQ; Xie LJ; Wang H; Zhu B; Wang SQ Prediction of selective estrogen receptor beta agonist using open data and machine learning approach. Drug Des Devel Ther 2016, 10, 2323–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhhatarai B; Wilson DM; Price PS; Marty S; Parks AK; Carney E Evaluation of OASIS QSAR Models Using ToxCast in Vitro Estrogen and Androgen Receptor Binding Data and Application in an Integrated Endocrine Screening Approach. Environ Health Perspect 2016, 124, (9), 1453–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russo DP; Kim MT; Wang W; Pinolini D; Shende S; Strickland J; Hartung T; Zhu H CIIPro: a new read-across portal to fill data gaps using public large-scale chemical and biological data. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, (3), 464–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim MT; Huang R; Sedykh A; Wang W; Xia M; Zhu H Mechanism Profiling of Hepatotoxicity Caused by Oxidative Stress Using Antioxidant Response Element Reporter Gene Assay Models and Big Data. Environ Health Perspect 2016, 124, (5), 634–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu H; Zhang J; Kim MT; Boison A; Sedykh A; Moran K Big data in chemical toxicity research: the use of high-throughput screening assays to identify potential toxicants. Chem Res Toxicol 2014, 27, (10), 1643–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayr A; Klambauer G; Unterthiner T; Hochreiter S DeepTox: toxicity prediction using deep learning. Front Environ Sci 2016, 3, 80. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdelaziz A; Spahn-Langguth H; Schramm K-W; Tetko IV Consensus modeling for HTS assays using in silico descriptors calculates the best balanced accuracy in Tox21 challenge. Front Environ Sci 2016, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korotcov A; Tkachenko V; Russo DP; Ekins S Comparison of Deep Learning With Multiple Machine Learning Methods and Metrics Using Diverse Drug Discovery Data Sets. Mol Pharm 2017, 14, (12), 4462–4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lane T; Russo DP; Zorn KM; Clark AM; Korotcov A; Tkachenko V; Reynolds RC; Perryman AL; Freundlich JS; Ekins S Comparing and Validating Machine Learning Models for Mycobacterium tuberculosis Drug Discovery. Mol Pharm 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inglese J; Auld DS; Jadhav A; Johnson RL; Simeonov A; Yasgar A; Zheng W; Austin CP Quantitative high-throughput screening: a titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, (31), 11473–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szymanski P; Markowicz M; Mikiciuk-Olasik E Adaptation of high-throughput screening in drug discovery-toxicological screening tests. Int J Mol Sci 2012, 13, (1), 427–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klekota J; Brauner E; Roth FP; Schreiber SL Using high-throughput screening data to discriminate compounds with single-target effects from those with side effects. J Chem Inf Model 2006, 46, (4), 1549–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidhuber J Deep learning in neural networks: an overview. Neural Netw 2015, 61, 85–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Capuzzi SJ; Politi R; Isayev O; Farag S; Tropsha A QSAR Modeling of Tox21 Challenge Stress Response and Nuclear Receptor Signaling Toxicity Assays. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2016, 4, (3). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russakovsky O; deng J; Su H; Krause J; Satheesh S; Ma S; Huang Z; Karpathy A; Khosla A; Bernstein M; Berg AC; Fei-Fei L ImageNet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int J Comp Vision 2015, 115, (3), 211–252. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ekins S The next era: Deep learning in pharmaceutical research. Pharm Res 2016, 33, 2594–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korotcov A; Tkachenko V; Russo DP; Ekins S Comparison of Deep Learning With Multiple Machine Learning Methods and Metrics Using Diverse Drug Discovery Datasets. Mol Pharm 2018, 14, 4462–4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aliper A; Plis S; Artemov A; Ulloa A; Mamoshina P; Zhavoronkov A Deep Learning Applications for Predicting Pharmacological Properties of Drugs and Drug Repurposing Using Transcriptomic Data. Mol Pharm 2016, 13, (7), 2524–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mamoshina P; Vieira A; Putin E; Zhavoronkov A Applications of Deep Learning in Biomedicine. Mol Pharm 2016, 13, (5), 1445–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark AM; Ekins S Open Source Bayesian Models: 2. Mining A “big dataset” to create and validate models with ChEMBL. J Chem Inf Model 2015, 55, 1246–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee AC; Shedden K; Rosania GR; Crippen GM Data mining the NCI60 to predict generalized cytotoxicity. J Chem Inf Model 2008, 48, (7), 1379–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang C; Tarkhov A; Marusczyk J; Bienfait B; Gasteiger J; Kleinoeder T; Magdziarz T; Sacher O; Schwab CH; Schwoebel J; Terfloth L; Arvidson K; Richard A; Worth A; Rathman J New publicly available chemical query language, CSRML, to support chemotype representations for application to data mining and modeling. J Chem Inf Model 2015, 55, (3), 510–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark AM Molecular Notebook. http://molmatinf.com/MolNote/

- 42.Clark AM; Dole K; Coulon-Spector A; McNutt A; Grass G; Freundlich JS; Reynolds RC; Ekins S Open source bayesian models: 1. Application to ADME/Tox and drug discovery datasets. J Chem Inf Model 2015, 55, 1231–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carletta J Assessing agreement on classification tasks: The kappa statistic. Computational Linguistics 1996, 22, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen J A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Education and Psychological Measurement 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matthews BW Comparison of the predicted and observed secondary structure of T4 phage lysozyme. Biochim Biophys Acta 1975, 405, (2), 442–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mansouri K; Abdelaziz A; Rybacka A; Roncaglioni A; Tropsha A; Varnek A; Zakharov A; Worth A; Richard AM; Grulke CM; Trisciuzzi D; Fourches D; Horvath D; Benfenati E; Muratov E; Wedebye EB; Grisoni F; Mangiatordi GF; Incisivo GM; Hong H; Ng HW; Tetko IV; Balabin I; Kancherla J; Shen J; Burton J; Nicklaus M; Cassotti M; Nikolov NG; Nicolotti O; Andersson PL; Zang Q; Politi R; Beger RD; Todeschini R; Huang R; Farag S; Rosenberg SA; Slavov S; Hu X; Judson RS CERAPP: Collaborative Estrogen Receptor Activity Prediction Project. Environ Health Perspect 2016, 124, (7), 1023–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caruana R; Niculescu-Mizil A In An empirical comparison of supervised learning algorithms 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning, Pittsburgh, PA, 2006; Pittsburgh, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 48.He J; Peng T; Yang X; Liu H Development of QSAR models for predicting the binding affinity of endocrine disrupting chemicals to eight fish estrogen receptor. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2018, 148, 211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao Q; Lu Y; Zhao Y; Li R; Luan F; Cordeiro MN Rational Design of Multi-Target Estrogen Receptors ERalpha and ERbeta by QSAR Approaches. Curr Drug Targets 2017, 18, (5), 576–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee S; Barron MG Structure-Based Understanding of Binding Affinity and Mode of Estrogen Receptor alpha Agonists and Antagonists. PLoS One 2017, 12, (1), e0169607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asako Y; Uesawa Y High-Performance Prediction of Human Estrogen Receptor Agonists Based on Chemical Structures. Molecules 2017, 22, (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang P; Dang L; Zhu BT Use of computational modeling approaches in studying the binding interactions of compounds with human estrogen receptors. Steroids 2016, 105, 26–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ribay K; Kim MT; Wang W; Pinolini D; Zhu H Predictive Modeling of Estrogen Receptor Binding Agents Using Advanced Cheminformatics Tools and Massive Public Data. Front Environ Sci 2016, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niinivehmas SP; Manivannan E; Rauhamaki S; Huuskonen J; Pentikainen OT Identification of estrogen receptor alpha ligands with virtual screening techniques. J Mol Graph Model 2016, 64, 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin TM Prediction of in vitro and in vivo oestrogen receptor activity using hierarchical clustering. SAR QSAR Environ Res 2016, 27, (1), 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang R; Sakamuru S; Martin MT; Reif DM; Judson RS; Houck KA; Casey W; Hsieh JH; Shockley KR; Ceger P; Fostel J; Witt KL; Tong W; Rotroff DM; Zhao T; Shinn P; Simeonov A; Dix DJ; Austin CP; Kavlock RJ; Tice RR; Xia M Profiling of the Tox21 10K compound library for agonists and antagonists of the estrogen receptor alpha signaling pathway. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 5664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ekins S, Computational Toxicology: Risk Assessment for Chemicals. John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ekins S Progress in computational toxicology. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 2014, 69, (2), 115–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bender A Bayesian methods in virtual screening and chemical biology. Methods Mol Biol 2011, 672, 175–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bender A; Scheiber J; Glick M; Davies JW; Azzaoui K; Hamon J; Urban L; Whitebread S; Jenkins JL Analysis of Pharmacology Data and the Prediction of Adverse Drug Reactions and Off-Target Effects from Chemical Structure. ChemMedChem 2007, 2, (6), 861–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cortes-Ciriano I; van Westen GJ; Lenselink EB; Murrell DS; Bender A; Malliavin T Proteochemometric modeling in a Bayesian framework. J Cheminform 2014, 6, 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paricharak S; Cortes-Ciriano I; AP IJ; Malliavin TE; Bender A Proteochemometric modelling coupled to in silico target prediction: an integrated approach for the simultaneous prediction of polypharmacology and binding affinity/potency of small molecules. J Cheminform 2015, 7, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clark AM; Dole K; Ekins S Open Source Bayesian Models: 3. Composite Models for prediction of binned responses. J Chem Inf Model 2016, 56, (J Chem Inf Model), 275–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anon Assay Central Website. www.assaycentral.org

- 65.Anon Assay Central video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTJJ6Tyu4bY&feature=youtu.be

- 66.Gawehn E; Hiss JA; Schneider G Deep Learning in Drug Discovery. Mol Inform 2016, 35, (1), 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu Y; Dai Z; Chen F; Gao S; Pei J; Lai L Deep Learning for Drug-Induced Liver Injury. J Chem Inf Model 2015, 55, (10), 2085–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lusci A; Pollastri G; Baldi P Deep architectures and deep learning in chemoinformatics: the prediction of aqueous solubility for drug-like molecules. J Chem Inf Model 2013, 53, (7), 1563–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ma J; Sheridan RP; Liaw A; Dahl GE; Svetnik V Deep neural nets as a method for quantitative structure-activity relationships. J Chem Inf Model 2015, 55, (2), 263–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goh GB; Hodas NO; Vishnu A Deep learning for computational chemistry. J Comput Chem 2017, 38, (16), 1291–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kearnes S; McCloskey K; Berndl M; Pande V; Riley P Molecular graph convolutions: moving beyond fingerprints. J Comput Aided Mol Des 2016, 30, (8), 595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen H; Engkvist O; Wang Y; Olivecrona M; Blaschke T The rise of deep learning in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jing Y; Bian Y; Hu Z; Wang L; Xie XS Deep Learning for Drug Design: an Artificial Intelligence Paradigm for Drug Discovery in the Big Data Era. AAPS J 2018, 20, (3), 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Altae-Tran H; Ramsundar B; Pappu AS; Pande V Low Data Drug Discovery with One-Shot Learning. ACS Cent Sci 2017, 3, (4), 283–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu K; Zhao Z; Wang R; Wei GW TopP-S: Persistent homology-based multi-task deep neural networks for simultaneous predictions of partition coefficient and aqueous solubility. J Comput Chem 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wen M; Zhang Z; Niu S; Sha H; Yang R; Yun Y; Lu H Deep-Learning-Based Drug-Target Interaction Prediction. J Proteome Res 2017, 16, (4), 1401–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lenselink EB; Ten Dijke N; Bongers B; Papadatos G; van Vlijmen HWT; Kowalczyk W; AP IJ; van Westen GJP Beyond the hype: deep neural networks outperform established methods using a ChEMBL bioactivity benchmark set. J Cheminform 2017, 9, (1), 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koutsoukas A; Monaghan KJ; Li X; Huan J Deep-learning: investigating deep neural networks hyper-parameters and comparison of performance to shallow methods for modeling bioactivity data. J Cheminform 2017, 9, (1), 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Steinbeck C; Hoppe C; Kuhn S; Floris M; Guha R; Willighagen EL Recent developments of the chemistry development kit (CDK) - an open-source java library for chemo-and bioinformatics. Curr Pharm Des 2006, 12, (17), 2111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuhn T; Willighagen EL; Zielesny A; Steinbeck C CDK-Taverna: an open workflow environment for cheminformatics. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anon RDKit: Open-Source Cheminformatics Software. www.rdkit.org

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.